Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Republic of Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

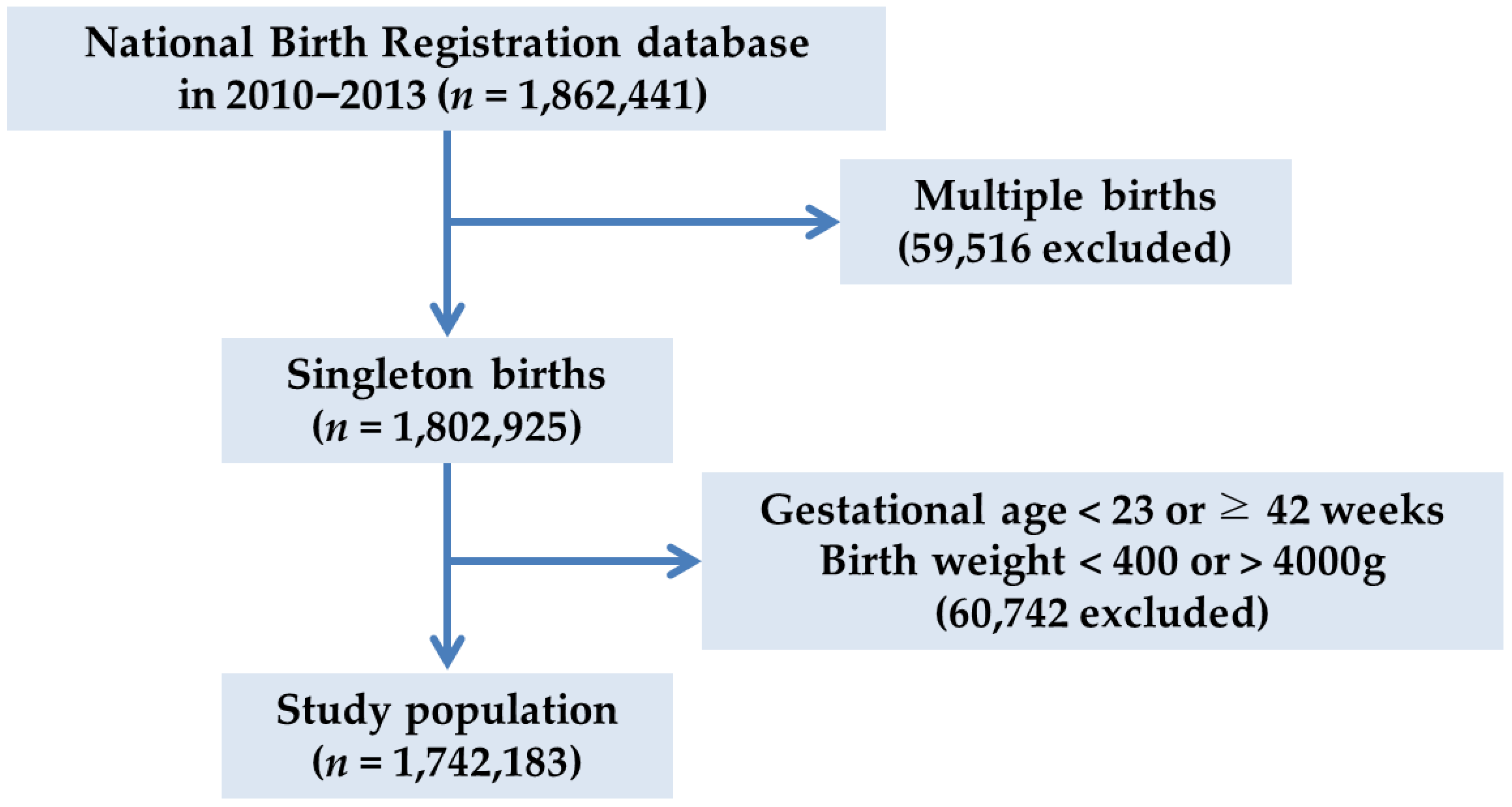

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Air Monitoring Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Birth-Related Characteristics

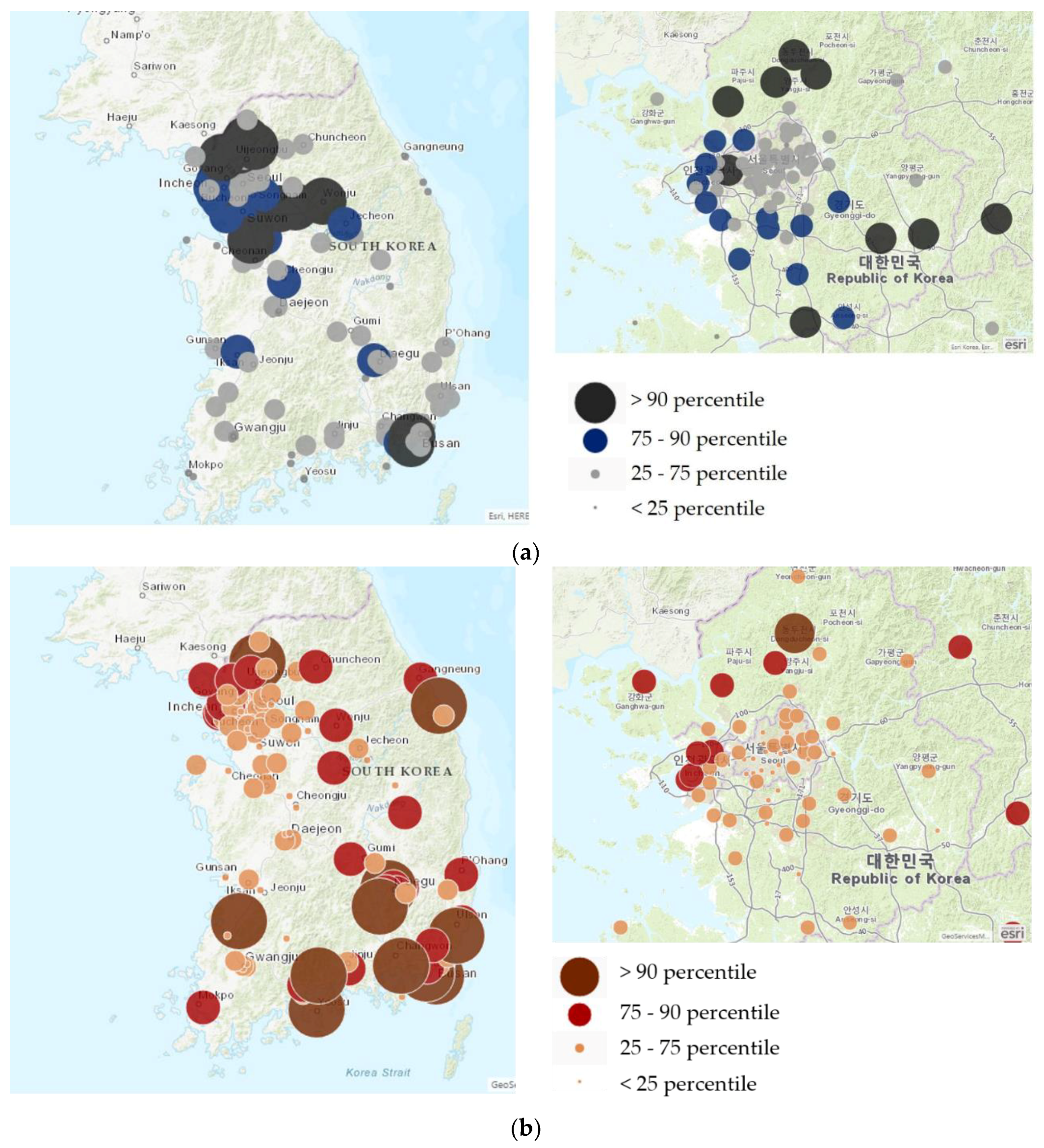

3.2. Distribution of PM10 and Preterm Births in Korea

3.3. PM10 and Birth Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Air Quality Guidelines: Global Update 2005. Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Sulfur Dioxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Xu, X.; Chu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Air particulate matter and cardiovascular disease: The epidemiological, biomedical and clinical evidence. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E8–E19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Andersen, Z.; Beelen, R.; Samoli, E.; Stafoggia, M.; Weinmayr, G.; Hoffmann, B.; Fischer, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Brunekreef, B.; et al. Air pollution and lung cancer incidence in 17 European cohorts: Prospective analyses from the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, I.C.; Hemkens, L.G.; Bucher, H.C.; Hoffmann, B.; Schindler, C.; Künzli, N.; Schikowski, T.; Probst-Hensch, N.M. Association between ambient air pollution and diabetes mellitus in Europe and North America: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015, 123, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, Z.J.; Hvidberg, M.; Jensen, S.S.; Ketzel, M.; Loft, S.; Sørensen, M.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution: A cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Andersen, Z.J.; Hvidberg, M.; Jensen, S.S.; Ketzel, M.; Sørensen, M.; Hansen, J.; Loft, S.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A. Air pollution from traffic and cancer incidence: A Danish cohort study. Environ. Health 2011, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, D.; Kim, J.E. Fine, ultrafine, and yellow dust: Emerging health problems in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2014, 29, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Hong, S.J. Ambient air pollution and allergic diseases in children. Korean J. Pediatr. 2012, 55, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Cui, H.; Lv, L.; Lin, X.; et al. Ambient air pollutant PM10 and risk of preterm birth in Lanzhou, China. Environ. Int. 2015, 76, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.-H.; Kaplan, B.M.; Shim, Y.K.; Pohl, H.R.; Gotway, C.A.; Bullard, S.M.; Rogers, J.F.; Smith, M.M.; Tylenda, C.A. Exposures to air pollutants during pregnancy and preterm delivery. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, M.; Lencar, C.; Tamburic, L.; Koehoorn, M.; Demers, P.; Karr, C. A cohort study of traffic-related air pollution impacts on birth outcomes. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischer, N.L.; Merialdi, M.; van Donkelaar, A.; Vadillo-Ortega, F.; Martin, R.V.; Betran, A.P.; Souza, J.P.; O’Neill, M.S. Outdoor air pollution, preterm birth, and low birth weight: Analysis of the world health organization global survey on maternal and perinatal health. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.; Giorgis-Allemand, L.; Bernard, C.; Aguilera, I.; Andersen, A.-M.N.; Ballester, F.; Beelen, R.M.; Chatzi, L.; Cirach, M.; Danileviciute, A.; et al. Ambient air pollution and low birth weight: A European cohort study (ESCAPE). Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.-H.; Leem, J.-H.; Ha, E.-H.; Kim, O.-J.; Kim, B.-M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Park, H.S.; Kim, H.C.; Hong, Y.C.; Kim, Y.J. Population-attributable risk of low birth weight related to PM10 pollution in seven Korean cities. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2010, 24, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhi, A.; Boyko, V.; Almagor, J.; Benenson, I.; Segre, E.; Rudich, Y.; Stern, E.; Lerner-Geva, L. The possible association between exposure to air pollution and the risk for congenital malformations. Environ. Res. 2014, 135, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, P.S.; Balkhair, T. on behalf of Knowledge Synthesis Group on Determinants of Preterm/LBW births. Air pollution and birth outcomes: A systematic review. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perera, F.P.; Rauh, V.; Whyatt, R.M.; Tsai, W.Y.; Tang, D.; Diaz, D.; Hoepner, L.; Barr, D.; Tu, Y.H.; Camann, D.; et al. Effect of prenatal exposure to airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1287–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon Hsu, H.H.; Mathilda Chiu, Y.H.; Coull, B.A.; Kloog, I.; Schwartz, J.; Lee, A.; Wright, R.O.; Wright, R.J. Prenatal particulate air pollution and asthma onset in urban children. Identifying sensitive windows and sex differences. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Bell, E.F.; Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Walsh, M.C.; Hale, E.C.; Newman, N.S.; Schibler, K.; Carlo, W.A.; et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2010, 126, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T.M.; Rehman Mian, M.O.; Nuyt, A.M. Long-term impact of preterm birth: Neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 2017, 44, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Child Mortality and Causes of Death. 2013. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/child_health/mortality/neonatal_text/en/ (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Lee, J.J. The low birth weight rate in Korea. Korean J. Perinatol. 2009, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Birth Trend Statistics in the Republic of Korea. Updated 2018. Available online: http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsListIndex.do?menuId=M_01_01&vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parmTabId=M_01_01?menuId=M_01_01&vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parmTabId=M_01_01&parentId=A#SubCont (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- NRP Neonatal Resuscitation Textbook, 6th ed.; English Version; American Heart Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011.

- Korea Environment Public Corporation Air Pollution Information Inquiry Service. Updated 2018. Available online: https://www.data.go.kr/dataset/15000581/openapi.do?lang=en (accessed on 12 July 2017).

- Air Quality Standards. Updated 2015. Available online: http://www.airkorea.or.kr/airStandardKorea (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Parker, J.D.; Schoendorf, K.C.; Kiely, J.L. Associations between measures of socioeconomic status and low birth weight, small for gestational age, and premature delivery in the United States. Ann. Epidemiol. 1994, 4, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Lim, H.-T.; Park, H.-Y.; Park, S.M.; Kim, H.-S. The associations of parental under-education and unemployment on the risk of preterm birth: 2003 Korean National Birth Registration database. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.G.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, H.-S.; Choi, S.; Kwon, S.; Park, S.M. Birth outcomes of immigrant women married to native men in the Republic of Korea: A population register-based study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, O.-J.; Ha, E.-H.; Kim, B.-M.; Seo, J.-H.; Park, H.-S.; Jung, W.-J.; Lee, B.E.; Suh, Y.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, J.T.; et al. PM10 and pregnancy outcomes: A hospital-based cohort study of pregnant women in Seoul. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 49, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.J.; Kim, H.; Seo, J.H.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, Y.C.; Ha, E.H. Different effects of PM10 exposure on preterm birth by gestational period estimated from time-dependent survival analyses. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merklinger-Gruchala, A.; Kapiszewska, M. Association between PM10 air pollution and birth weight after full-term pregnancy in Krakow city 1995–2009—Trimester specificity. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2015, 22, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ji, Y.; Kang, S.; Dong, T.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Wu, W.; Tang, Q.; Chen, T.; et al. Effects of particulate matter exposure during pregnancy on birth weight: A retrospective cohort study in Suzhou, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaborators GBDRF. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1345–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieb, D.M.; Chen, L.; Eshoul, M.; Judek, S. Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2012, 117, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimou, B.; Salihu, H.M.; Gasana, J.; Owusu, H. Risk of low birth weight and very low birth weight from exposure to particulate matter (PM2.5) speciation metals during pregnancy. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 4, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Planetary Health. Welcome to The Lancet Planetary Health. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) or Mean (SD) (n = 1,742,183) |

|---|---|

| Infant sex | |

| Male | 888,711 (51.0) |

| Female | 853,472 (49.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 1,703,795 (97.9) |

| Unmarried | 36,857 (2.1) |

| Paternal age (years) | |

| Mean | 33.7 (4.6) |

| <20 | 2752 (0.2) |

| 20–29 | 268,567 (15.6) |

| 30–39 | 1,282,258 (74.3) |

| ≥40 | 172,350 (10.0) |

| Maternal age (years) | |

| Mean | 31.0 (4.1) |

| <20 | 10,707 (0.6) |

| 20–34 | 1,414,366 (81.2) |

| ≥35 | 316,175 (18.2) |

| Area of birth | |

| Capital region | 885,157 (50.8) |

| Others | 857,026 (49.2) |

| Place of birth | |

| Hospital | 1,713,436 (98.4) |

| Others | 27,627 (1.6) |

| Paternal education | |

| University or higher | 1,227,626 (71.2) |

| High school or lower | 495,918 (28.8) |

| Maternal education | |

| University or higher | 1,215,714 (70.0) |

| High school or lower | 521,532 (28.0) |

| Paternal employment | |

| Manager or specialist | 477,105 (27.4) |

| Officer | 585,437 (33.6) |

| Service | 296,117 (17.0) |

| Blue collar | 317,360 (18.2) |

| Unemployed a | 66,164 (3.8) |

| Maternal employment | |

| Manager or specialist | 221,519 (12.7) |

| Officer | 245,619 (14.1) |

| Service | 78,395 (4.5) |

| Blue | 34,344 (2.0) |

| Unemployed a | 1,162,306 (66.7) |

| Paternal nationality | |

| Korean | 1,715,981 (99.4) |

| Non-Korean | 11,048 (0.6) |

| Maternal nationality | |

| Korean | 1,679,145 (96.5) |

| Non-Korean | 60,629 (3.5) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparous | 899,141 (51.7) |

| Multiparous | 840,365 (48.3) |

| Mean gestational age (weeks) | 38.7 (1.5) |

| Preterm infants | 82,524 (4.7) |

| Mean birthweight (kg) | 3.2 (0.4) |

| Low birthweight in term infants | 28,728 (1.7 b) |

| PM10 (µg/m3) | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st centile | 12 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 13 | 11 |

| 25th centile | 33 | 30 | 30 | 28 | 30 | 30 |

| Median | 46 | 45 | 44 | 40 | 43 | 44 |

| Mean | 53 | 51 | 50 | 45 | 49 | 50 |

| 75th centile | 65 | 64 | 62 | 56 | 60 | 62 |

| 90th centile | 91 | 88 | 84 | 76 | 82 | 84 |

| 99th centile | 167 | 170 | 179 | 118 | 139 | 156 |

| Range | 155 | 160 | 170 | 108 | 126 | 145 |

| Exposure | Proportion (%) | P-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low birthweights in term infants | 1st–3rd | 1.7 | ||

| 4th | 1.8 | 0.495 | 1.010 (0.981–1.040) | |

| ≤70 µg/m3 | 1.7 | |||

| >70 µg/m3 | 1.9 | 0.283 | 1.060 (0.953–1.177) | |

| Preterm infants | 1st–3rd | 4.7 | ||

| 4th | 4.9 | <0.001 | 1.044 (1.025–1.062) | |

| ≤70 µg/m3 | 4.7 | |||

| >70 µg/m3 | 7.4 | <0.001 | 1.570 (1.487–1.656) | |

| Very preterm infants (Gestational age < 32 weeks) | 1st–3rd | 1.0 | ||

| 4th | 1.1 | <0.001 | 1.095 (1.055–1.137) | |

| ≤70 µg/m3 | 1.0 | |||

| >70 µg/m3 | 2.0 | <0.001 | 1.966 (1.776–2.177) |

| Exposure | Proportion (%) | P-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan areas | 1st–3rd | 4.6 | ||

| 4th | 5.4 | <0.001 | 1.156 (1.123–1.190) | |

| ≤70 µg/m3 | 4.7 | |||

| >70 µg/m3 | 8.9 | <0.001 | 1.934 (1.666–2.247) | |

| Non-metropolitan regions | 1st–3rd | 4.7 | ||

| 4th | 4.7 | 0.127 | 0.984 (0.963–1.006) | |

| ≤70 µg/m3 | 4.7 | |||

| >70 µg/m3 | 7.2 | <0.001 | 1.521 (1.436–1.611) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.J.; Song, I.G.; Kim, K.-N.; Kim, M.S.; Chung, S.-H.; Choi, Y.-S.; Bae, C.-W. Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Republic of Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040633

Kim YJ, Song IG, Kim K-N, Kim MS, Chung S-H, Choi Y-S, Bae C-W. Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Republic of Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(4):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040633

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yu Jin, In Gyu Song, Kyoung-Nam Kim, Min Sun Kim, Sung-Hoon Chung, Yong-Sung Choi, and Chong-Woo Bae. 2019. "Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Republic of Korea" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 4: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040633

APA StyleKim, Y. J., Song, I. G., Kim, K.-N., Kim, M. S., Chung, S.-H., Choi, Y.-S., & Bae, C.-W. (2019). Maternal Exposure to Particulate Matter during Pregnancy and Adverse Birth Outcomes in the Republic of Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040633