Repeated Police Mental Health Act Detentions in England and Wales: Trauma and Recurrent Suicidality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Police Survey

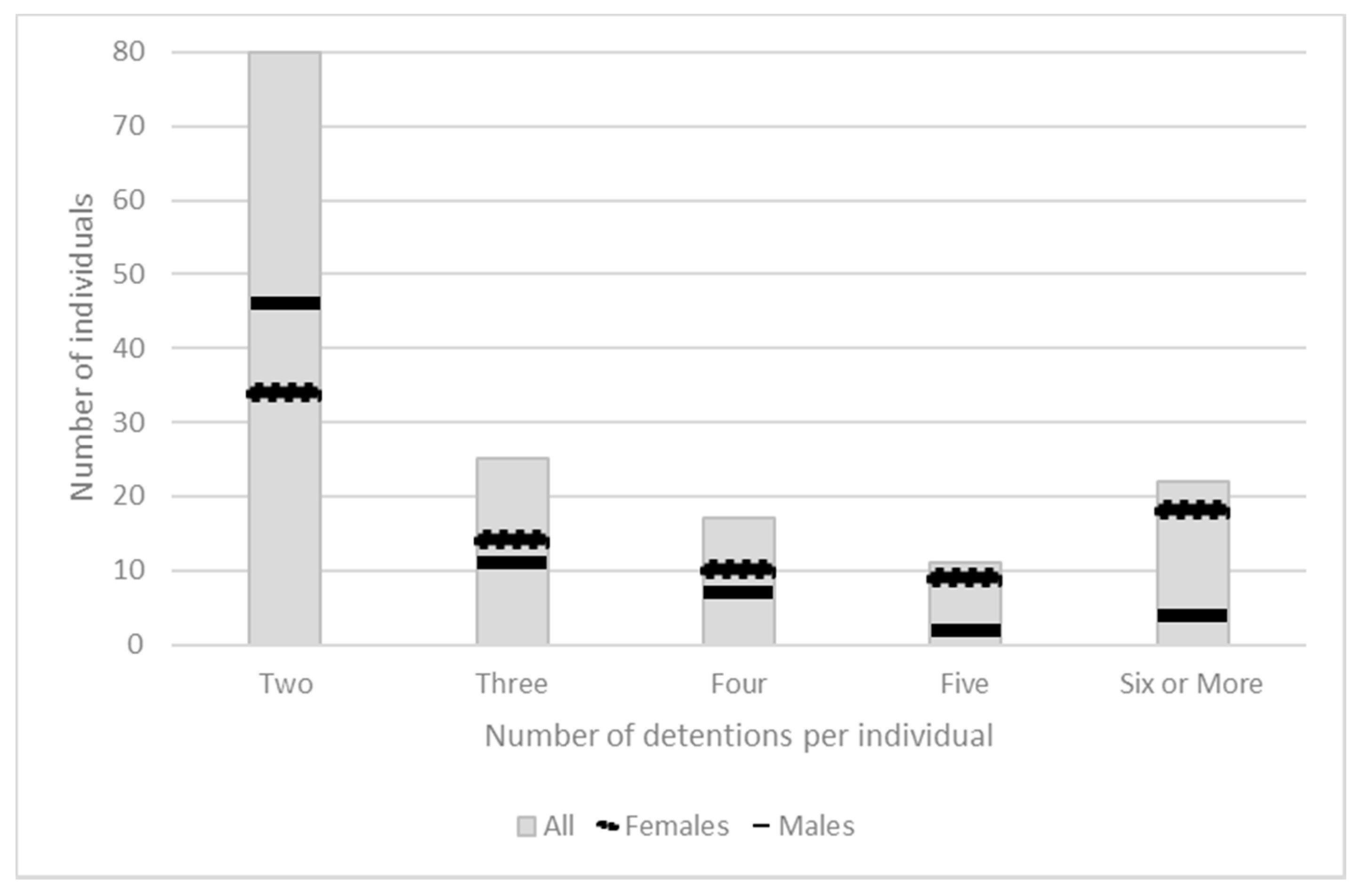

2.3. South East Regional Detention Data

2.4. Lived Experience Interviews

2.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.6. Ethics

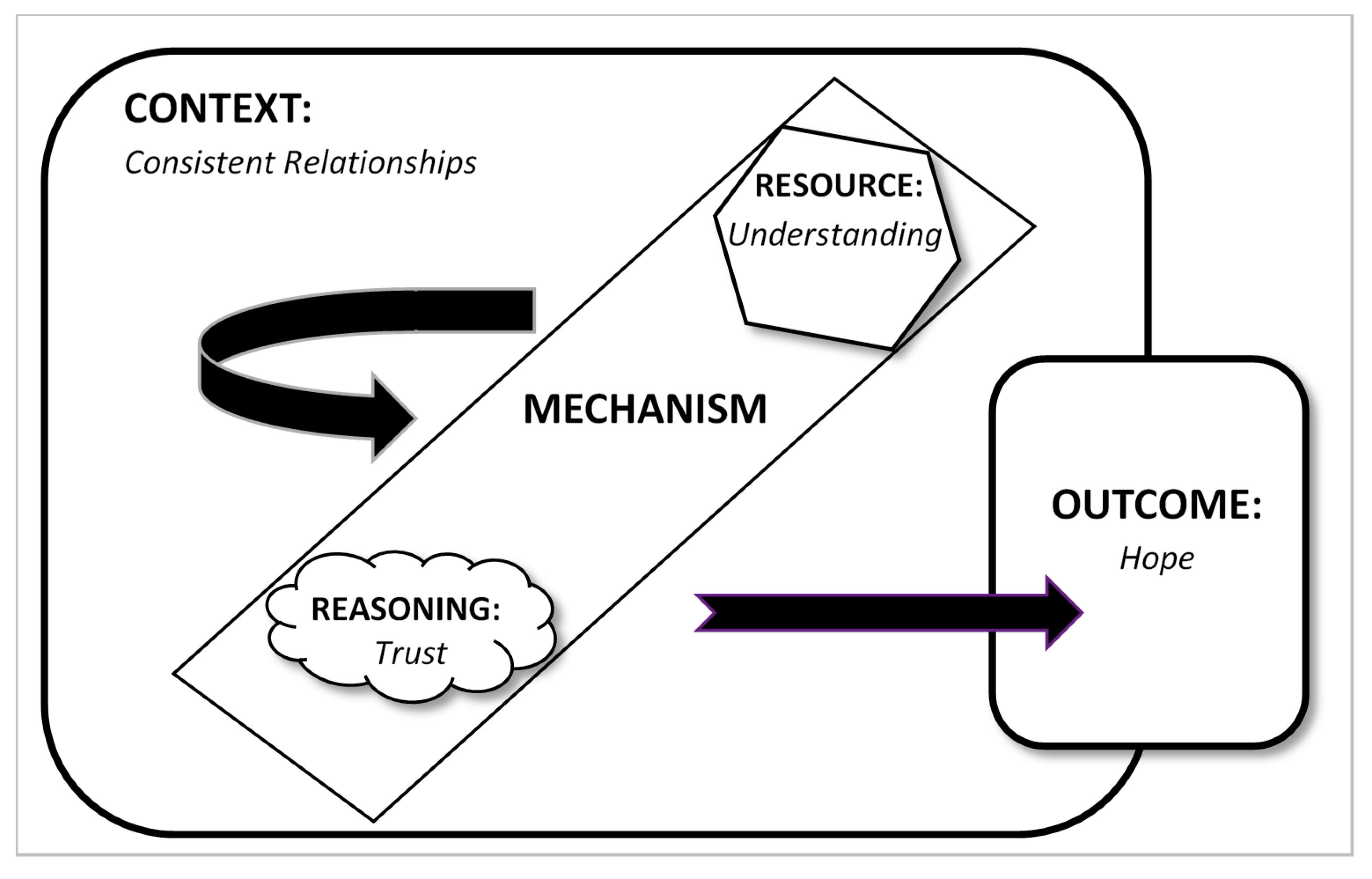

3. Findings

3.1. Service Perspectives on Repeated Detention

3.2. Lived Experience of Repeated Suicidal Crises

“I see my psychotherapist once a week, he is probably the only person who understands me. But him understanding me doesn’t change my life.”

“You know they do get to know you, and I think their sort of ethos is to get you to bond with the whole team rather than just the one person. So you do have a key worker but there’s always somebody else there …so you’ve got the whole team really not just one person.”

“they work as a team. Know you as a team. And that makes me feel a lot safer. That makes me feel listened to. I feel supported. I feel like the staff understand… the nature of this illness. How it affects us.”

“I’ve failed at my marriage. I’ve failed at being a parent. Suicide’s just another thing I’ve failed at.”

“I was taking regular overdoses, probably monthly, because I just couldn’t manage the feelings… I couldn’t manage feeling such a failure. I couldn’t manage… the pain of living. I couldn’t see that it would ever end.”

“they didn’t communicate to me the reasons why they wouldn’t work with me. I felt rejected and abandoned. And like no one cared about what would happen to me.”

“The attitude of services is ‘if you have a personality disorder diagnosis, we can’t help you’.”

“when I got to [name of hospital] I felt safe, and calm, and then the doctor, the next day turned round and says ‘Yeah, oh yeah I know her she’s ok, I’ll take her off Section. She can go home’.”

“I’m too frightened to ask for help for fear of rejection and then feeling even more alone. So, I won’t ask for a hospital admission… I wonder how much the mental health system has contributed to me feeling constantly suicidal.”

“The police are the only people who have to do something. They can’t leave you... So, I have really mixed feelings on 136.”

“Everything that happens is merely a sticking plaster until the next 136. [Services] know it. I know it. [so] half of me wants some help, the other half wants to be dead.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Greenberg, N.; Lloyd, K.; O’Brien, C.; McIver, S.; Hessford, A.; Donovan, M. A Prospective Survey of Section 136 in Rural England (Devon and Cornwall). Med. Sci. Law 2002, 42, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menkes, D.B.; Bendelow, G.A. Diagnosing vulnerability and “dangerousness”: Police use of Section 136 in England and Wales. J. Public Ment. Health 2014, 13, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health, Home Office. Review of Sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act (1983) Review Report and Recommendations; Department of Health: London, UK, 2014.

- HMIC. A Criminal Use of Police Cells? The Use of Police Custody as a Place of Safety for People with Mental Health Needs; Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary: London, UK, 2013.

- The Royal College of Emergency Medicine. An Investigation into Care of People Detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act Who Are Brought to Emergency Departments in England and Wales; The Royal College of Emergency Medicine: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services. Policing and Mental Health: Picking up the Pieces; HMICFRS: London, UK, 2018.

- Borschmann, R.D.; Gillard, S.; Turner, K.; Lovell, K.; Goodrich-Purnell, N.; Chambers, M. Demographic and referral patterns of people detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act (1983) in a south London Mental Health Trust from 2005 to 2008. Med. Sci. Law 2010, 50, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, I. Policing and Mental Illness in England and Wales post Bradley. Policing 2012, 6, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home Office. Police Powers and Procedures England and Wales Year, Ending 31 March 2019, 2019.

- Thomas, A.; Forrester-Jones, R. Understanding the Changing Patterns of Behaviour Leading to Increased Detentions by the Police under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Polic. A J. Policy Pract. 2018, 13, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, J.; Pugh, D.; Riley, G.; Hovey, N. The use of section 136 (Mental Health Act 1983) in Gloucestershire. Med. Sci. Law 2010, 50, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Department of Health; Home Office. Review of the Operation of Sections 135 and 136 of the Mental Health Act 1983: A Literature Review; Department of Health: London, UK, 2014.

- Bendelow, G.; Warrington, C.A.; Jones, A.-M.; Markham, S. Police detentions of ‘mentally disordered persons’: A multi-method investigation of section 136 use in Sussex. Med. Sci. Law 2019, 59, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, T.H.; Ness, M.N.; Imison, C.T. “Mentally disordered persons found in public places” Diagnostic and social aspects of police referrals (Section 136). Psychol. Med. 1992, 22, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G.; Laidlaw, J.; Pugh, D.; Freeman, E. The responses of professional groups to the use of Section 136 of the Mental Health Act (1983, as amended by the 2007 Act) in Gloucestershire. Med. Sci. Law 2011, 5, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, K.T.; Moghal, A.; Mahadun, P. Section 136 assessments in Trafford Borough of Manchester. Clin. Gov. 2011, 16, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipe, R.; Bhat, A.; Matthews, B.; Hampstead, J. Section 136 and African/Afro-Caribbean minorities. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 1991, 37, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, S.A.; McPhillips, M.A. Personality Disorder and Police Section 136 in Westminster: A Retrospective Analysis of 65 Assessments over Six Months. Med. Sci. Law 1995, 35, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P.; Matheson-Monnet, C. Multi-agency mentoring pilot intervention for high intensity service users of emergency public services: The Isle of Wight Integrated Recovery Programme. J. Criminol. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 3, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J. Cracked: Why Psychiatry Is Doing More Harm Than Good; Icon Books: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Timimi, S. No more psychiatric labels: Why formal psychiatric diagnostic systems should be abolished. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2014, 14, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanheule, S.; Adriaens, P.; Bazan, A.; Bracke, P.; Devisch, I.; Feys, J.-L.; Froyen, B.; Gerard, S.; Nieman, D.H.; Van Os, J.; et al. Belgian Superior Health Council advises against the use of the DSM categories. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Proctor, G. Women at the Margins: A Critique of the Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder. Fem. Psychol. 2005, 15, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendelow, G. Ethical aspects of personality disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2010, 23, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, N. Borderline personality disorder: The voice of patients. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, R.; Black, D.W.; Blum, N. Systems Training for Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving (STEPPS) in the United Kingdom: A Preliminary Report. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2010, 40, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gask, L.; Evans, M.; Kessler, D. Clinical Review. Personality disorder. BMJ 2013, 347, f5276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichsenring, F.; Leibing, E.; Kruse, J.; New, A.; Leweke, F. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2011, 377, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton-Howes, G.; Tyrer, P.; Anagnostakis, K.; Cooper, S.; Bowden-Jones, O.; Weaver, T. The prevalence of personality disorder, its comorbidity with mental state disorders, and its clinical significance in community mental health teams. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, B.; First, M.B. Application of the ICD-11 classification of personality disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, G.; Appleby, L. Personality disorder: The patients psychiatrists dislike. Br. J. Psychiatry 1988, 153, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzer, S.H. Does “difficult patient” status contribute to de facto demedicalization? The case of borderline personality disorder. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 142, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Sethi, F.; Dale, O.; Stanton, C.; Sedgwick, R.; Doran, M.; Shoolbred, L.; Goldsack, S.; Haigh, R. Personality disorder service provision: A review of the recent literature. Ment. Health. Rev. 2017, 22, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisti, D.; Segal, A.G.; Siegel, A.M.; Johnson, R.; Gunderson, J. Diagnosing, Disclosing, and Documenting Borderline Personality Disorder: A Survey of Psychiatrists’ Practices. J. Pers. Disord. 2016, 30, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, S.; Shea, M.T.; Battle, C.L.; Johnson, D.M.; Zlotnick, C.; Dolan-Sewell, R.; Skodol, A.E.; Grilo, C.M.; Gunderson, J.G.; Sanislow, C.A.; et al. Traumatic Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Borderline, Schizotypal, Avoidant, and Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorders: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, S.R.; Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Williamson, D.F.; Giles, W.H. Childhood Abuse, Household Dysfunction, and the Risk of Attempted Suicide Throughout the Life Span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA 2001, 286, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Adult Health. Acad. Pediatr. 2009, 9, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.J.; Arseneault, L.; Caspi, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Matthews, T.; Moffitt, T.E.; Odgers, C.L.; Stahl, D.; Teng, J.Y.; Danese, A. The epidemiology of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in a representative cohort of young people in England and Wales. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltgen, A.; Arbona, C.; Frankel, L.; Frueh, B.C. Interpersonal trauma, attachment insecurity and anxiety in an inpatient psychiatric population. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 35, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, M.; Fok, Y.; Hayes, R.D.; Chang, C.-K.; Stewart, R.; Callard, F.J. Life expectancy at birth and all-cause mortality among people with personality disorder. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 73, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temes, C.M.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Zanarini, M.C. Deaths by Suicide and Other Causes Among Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and Personality-Disordered Comparison Subjects Over 24 Years of Prospective Follow-Up. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.; While, D.; Mok, P.L.H.; Windfuhr, K.; Ashcroft, D.M.; Kontopantelis, E.; Chew-Graham, C.A.; Appleby, L.; Shaw, J.; Webb, R.T. Suicide risk in primary care patients diagnosed with a personality disorder: A nested case control study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for National Statistics. Suicides in the UK: 2018 Registrations; ONS: London, UK, 2019.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; WHO: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beghi, M.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Cerri, C.; Cornaggia, C.M. Risk factors for fatal and nonfatal repetition of suicide attempts: A literature review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis Treat. 2013, 9, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; Sage: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office. Police Powers and Procedures England and Wales Year, Ending 31 March 2017, 2017.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallon, P. Travelling through the system: The lived experience of people with borderline personality disorder in contact with psychiatric services. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2003, 10, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, D.; Byng, R.; Webber, M.; Enki, G.; Porter, I.; Larsen, J.; Huxley, P.; Pinfold, V. Personal well-being networks, social capital and severe mental illness: Exploratory study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 21, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, J. Moral Injury. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2014, 31, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Boyle, M.; Cromby, J.; Dillon, J.; Harper, D.; Kinderman, P.; Longden, E.; Pilgrim, D.; Read, J. The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the Identification of Patterns in Emotional Distress, Unusual Experiences and Troubled or Troubling Behaviour, as an Alternative to Functional Psychiatric Diagnosis; British Psychological Society: Leicester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, G.; Freeman, E.; Laidlaw, J.; Pugh, D. “A Frightening Experience”: detainees’ and carers’ experiences of being detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act. Med. Sci. Law 2011, 51, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, S.; John Chuan, S. Evaluation of the Impact Personality Disorder Project—A psychologically-informed consultation, training and mental health collaboration approach to probation offender management. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2016, 26, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solts, B.; Harvey, R. Working with People with Personality Disorder, 2nd ed.; Davey, G., Lake, N., Eds.; Routledge: Hove, UK, 2015; pp. 150–166. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, D.; Trower, P. The effects of the psychiatric label “borderline personality disorder” on nursing staff’s perceptions and causal attributions for challenging behaviours. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 42, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, G.L.; Lamont, E.; Mullen, J.; MacArthur, N.; Stirling, F.J. Mixed-methods evaluation of an educational intervention to change mental health nurses’ attitudes to people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 2613–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, O.; Gibson, S.; Boden, V.R.; Owen, G. Exhausted without trust and inherent worth: A model of the suicide process based on experiential accounts. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 163, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Buchman-Schmitt, J.M.; Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Tucker, R.P.; Hagan, C.R.; Rogers, M.L.; Podlogar, M.C.; Chiurliza, B.; Ringer, F.B.; et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 143, 1313–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, R.C.; Kirtley, O.J. The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 373, 20170268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasiński, D.; Ziółkowska, J. Experience of suicidal thoughts: A discourse analytic study. Commun. Med. 2013, 10, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiner, M.; Scourfield, J.; Fincham, B.; Langer, S. When things fall apart: Gender and suicide across the life-course. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byng, R.; Howerton, A.; Owens, C.V.; Campbell, J. Pathways to suicide attempts among male offenders: The role of agency. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 936–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | Dataset Length | Total Number of | Proportion of | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detentions in Dataset | People in Dataset | Repeated Detentions | People Detained Repeatedly | ||

| A * | 28 months | 2611 | 2203 | 22% | 7% |

| A | 12 months | 1421 | 1142 | 30% | 13% |

| B | 36 months | 1091 | 821 | 37% | 16% |

| C | 12 months | 171 | 69 | 32% | 12% |

| D | 6 months | 601 | 475 | 32% | 13% |

| Average | 1179 | 942 | 31% | 12% | |

| Characteristics | Number of Associated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detentions | Individuals | |||

| Females with sole diagnoses of a personality disorder | 229 | (48%) | 49 | (38%) |

| Females with any other diagnoses | 102 | (21%) | 50 | (39%) |

| All males in dataset (all diagnoses) | 145 | (31%) | 29 | (23%) |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Warrington, C. Repeated Police Mental Health Act Detentions in England and Wales: Trauma and Recurrent Suicidality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234786

Warrington C. Repeated Police Mental Health Act Detentions in England and Wales: Trauma and Recurrent Suicidality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(23):4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234786

Chicago/Turabian StyleWarrington, Claire. 2019. "Repeated Police Mental Health Act Detentions in England and Wales: Trauma and Recurrent Suicidality" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 23: 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234786

APA StyleWarrington, C. (2019). Repeated Police Mental Health Act Detentions in England and Wales: Trauma and Recurrent Suicidality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4786. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234786