Cognitive Reframing of Intimate Partner Aggression: Social and Contextual Influences

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Importance of Cognitive Reframing

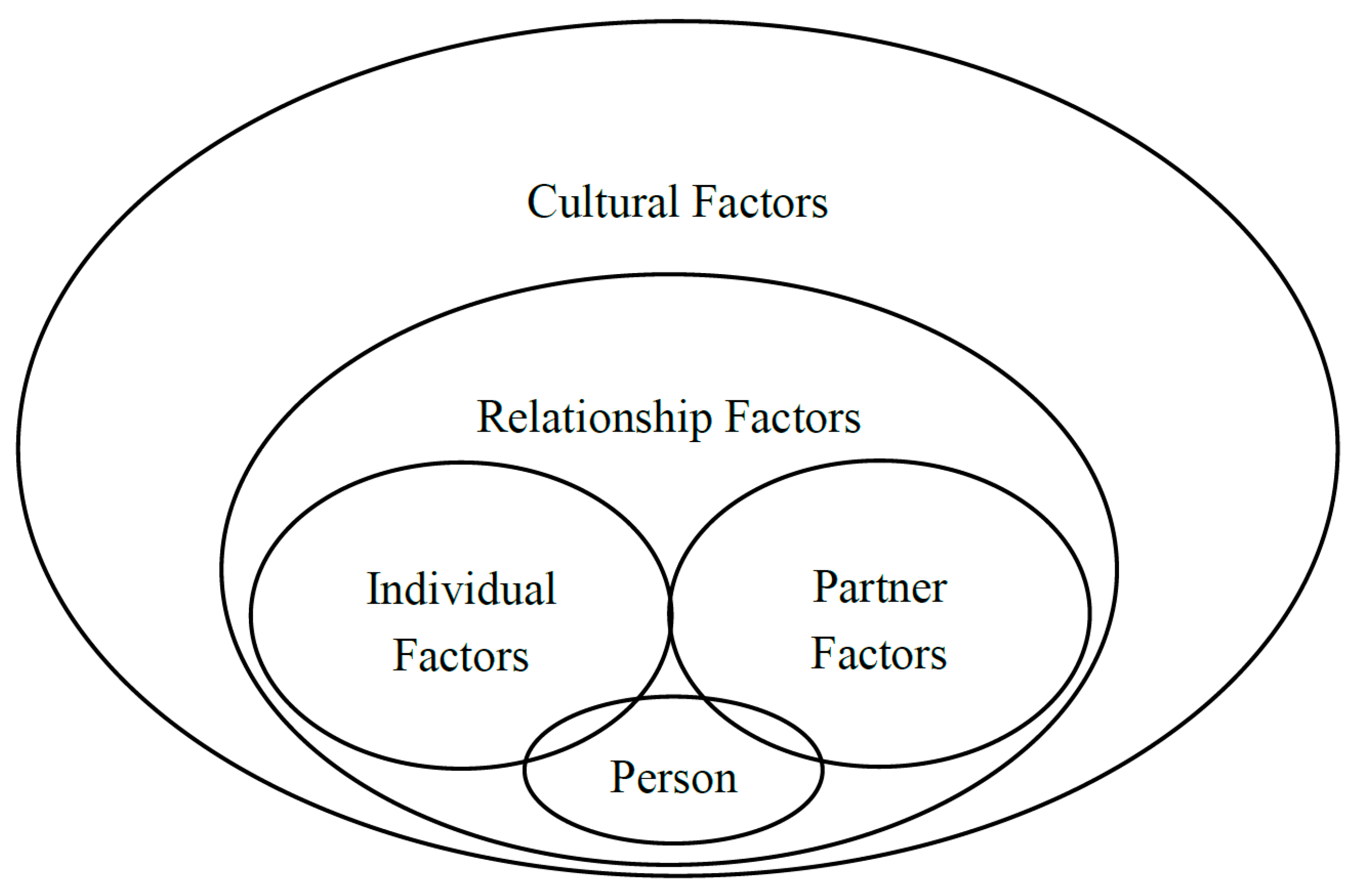

1.2. Gaining a Comprehensive View: An Ecological Approach

1.3. Interview Data

2. Four Levels of Influence

2.1. Individual Influences and Self-Blame

“I just assumed, ‘Well, maybe I did do something wrong. I shouldn’t have let his friend come into the house and stand there asking me where my husband was.’ Maybe I should have seen his friend pull up and gone outside and said, ‘He’s not here.’ Maybe there was something else I could have done… because most of the things that happened with him occurred when he was drunk. There must be something that I’m doing wrong if he’s hitting me or beating me up…. I might have done something wrong. You know, nobody deserves to get treated that way, but I didn’t know back then… I was young. Maybe he’s right. Maybe there’s something that I’m doing wrong.”

2.2. Partner Influences and “Uncontrollable Personality”

“He wasn’t a violent person… he’s a disabled veteran… post-traumatic stress disorder. Things happened when he was having a flashback, or if he was drinking. It was mainly at night while he’s asleep… if I would move, it would startle him, and he didn’t know where he was. Sometimes he’d grab me and put his fist in my face and stop short of my nose. One time he choked me. He was yelling at me in a language I didn’t understand and choking me. Most of it really was verbal, emotional… a lot of manipulating, manipulation. Then he realized where he was and who I was… but he’d been drinking, so he didn’t remember it. I just spent the night in a corner, terrified.”

2.3. Relationship Influences and “For Better or Worse”

“Well, we were together for many years, and it was that we had so much invested in it… It’s not his fault, he’s a veteran, for better or for worse… and I didn’t want to take his son away from him. I wanted his son to have a father. So many years of marriage invested…. He couldn’t take care of himself because he’s ill, and I didn’t want to take my son and I didn’t want to be away from my son.”

2.4. Cultural Influences and Redefining Violence

“The only thing he’s really done is pushed. He threw a stand at me… but it didn’t hit me. He knows if he hits me, he’ll get his gun permit taken away. So he’s never really used his hands on me. He hit my daughter. He’s thrown several things at me. He’s kicked me. But that’s it… [Someone] broke [the furniture]. And it made him mad. That’s when he threw [the furniture] at me and punched the walls…. I’ve been lucky with him not hitting me. It’s mainly been kicking or shoving. I thought things would work out. Because sometimes people do have a temper, but then things do work out.”

3. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deutsch, M.; Gerard, H.B. A Study of Normative and Informational Social Influences upon Individual Judgment. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1955, 51, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Frieze, I.H. Young singles contemporary dating scripts. Sex Roles 1993, 28, 449–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, W.; Gagnon, J.H. Sexual scripts—Permanence and change. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1986, 15, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus, M.A. The controversy over domestic violence by women—A methodological, theoretical, and sociology of science analysis. In Violence Intimate Relationships; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Cobb, R.J.; Daly, C.A. Aggression and violence in romantic relationships. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships, 2nd ed.; Vangelisti, A., Perlman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, I.; Pape, K.T. Psychological Abuse: Implications for Adjustment and Commitment to Leave Violent Partners. Violence Vict. 1999, 14, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Follingstad, D.R.; Rutledge, L.L.; Berg, B.J.; Hause, E.S.; Polek, D.S. The Role of Emotional Abuse in Physically Abusive Relationships. J. Fam. Violence 1990, 5, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.; Yoon, J.; Langer, A.; Ro, E. Is Psychological Aggression as Detrimental as Physical Aggression? The Independent Effects of Psychological Aggression on Depression and Anxiety Symptoms. Violence Vict. 2009, 24, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Capezza, N.M. The Paradox of Partner Aggression: Being Committed to an Aggressive Partner. In Human Aggression and Violence: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences; Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 367–383. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L.; Carlsmith, J.M. Cognitive Consequences of Forced Compliance. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1959, 58, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, G.J.O.; Fitness, J.; Blampied, N.M. The Link between Attributions and Happiness in Close Relationships: The Roles of Depression and Explanatory Style. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 9, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, J.N.; Fincham, F.D. Victim and Perpetrator Accounts of Interpersonal Transgressions: Self-Serving or Relationship-Serving Biases? Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 2005, 31, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, X.B. Joking Violence Among Highly Committed Individuals. J. Interpers. Violence 2002, 17, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human-Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Ceci, S.J. Nature-Nurture Reconceptualized in Developmental Perspective—A Bioecological Model. Psychol. Rev. 1994, 101, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U.; Evans, G.W. Developmental Science in the 21st Century: Emerging Questions, Theoretical Models, Research Designs and Empirical Findings. Soc. Dev. 2000, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. Inter. Encycl. Educ. 1994, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, J. Preliminary Study of Some Ecological Correlates of Child-Abuse—Impact of Socioeconomic Stress on Mothers. Child Dev. 1976, 47, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicchetti, D.; Lynch, M. Toward an Ecological Transactional Model of Community Violence and Child Maltreatment—Consequences for Childrens Development. Psychiatry 1993, 56, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, S.A.; Luster, T. Adolescent Sexual-Activity—An Ecological, Risk-Factor Approach. J. Marriage Fam. 1994, 56, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raine, K. Ecological Models Revisited: Their Uses and Evolution in Health Promotion Over Two Decades. Annu. Rev. Publiv Health 2011, 32, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banyard, V.L. Who Will Help Prevent Sexual Violence: Creating an Ecological Model of Bystander Intervention. Psychol. Violence 2011, 1, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.R.; Lund, E.M. Bronfenbrenner’s theoretical framework adapted to women with disabilities experiencing intimate partner violence. In Religion, Disability, and Interpersonal Violence; Johnson, A.J., Nelson, J.R., Lund, E.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nurius, P.S.; Norris, J. A cognitive ecological model of women’s response to male sexual coercion in dating. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 1995, 8, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slep, A.M.S.; Foran, H.M.; Heyman, R.E.; Snarr, J.D. Unique Risk and Protective Factors for Partner Aggression in a Large Scale Air Force Survey. J. Commun. Health 2010, 35, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.; Dworkin, E.; Cabral, G. An Ecological Model of the Impact of Sexual Assault on Women’s Mental Health. Trauma Violence Abus. 2009, 10, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, D.S.; Sussman, S.; Unger, J.B. A Further Look at the Intergenerational Transmission of Violence: Witnessing Interparental Violence in Emerging Adulthood. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1022–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrensaft, M.K.; Cohen, P.; Brown, J.; Smailes, E.; Chen, H.N.; Johnson, J.G. Intergenerational Transmission of Partner Violence: A 20-Year Prospective Study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Capezza, N.M.; Daly, C.A. Personal Standards for Judging Aggression by a Relationship Partner: How Much Aggression is Too Much? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, D.G.; Bodnarchuk, M.; Kropp, R.; Hart, S.D.; Ogloff, J.P. Client Personality Disorders Affecting Wife Assault Post-Treatment Recidivism. Violence Vict. 1997, 12, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, A.; Meehan, J.C.; Herron, K.; Rehman, U.; Stuart, G.L. Testing the Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) batterer typology. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 1000–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, N.; Gottman, J. When Men Batter Women: New Insights into Ending Abusive Relationships; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworthmunroe, A.; Stuart, G.L. Typologies of Male Batterers—3 Subtypes and the Differences among Them. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 476–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.M.; Orcutt, H.K. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Male-Perpetrated Intimate Partner Violence. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009, 302, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, A.C.; Beckham, J.C.; Calhoun, P.S.; Roberts, S.T.; Taft, C.T.; Elbogen, E.B.; Dennis, M.F. An Examination of General Aggression and Intimate Partner Violence in Women with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Violence Vict. 2012, 27, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semiatin, J.N.; Torres, S.; LaMotte, A.D.; Portnoy, G.A.; Murphy, C.M. Trauma Exposure, PTSD Symptoms, and Presenting Clinical Problems Among Male Perpetrators of Intimate Partner Violence. Psychol. Violence 2017, 7, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taft, C.T.; Schumm, J.; Orazem, R.J.; Meis, L.; Pinto, L.A. Examining the Link Between Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Dating Aggression Perpetration. Violence Vict. 2010, 25, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, K.R.; Bohnert, K.M.; Sripada, R.K.; Rauch, S.A.M.; Epstein-Ngo, Q.M.; Chermack, S.T. Associations Between PTSD and Intimate Partner and Non-Partner Aggression among Substance Using Veterans in Specialty Mental Health. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creech, S.K.; Macdonald, A.; Benzer, J.K.; Poole, G.M.; Murphy, C.M.; Taft, C.T. PTSD Symptoms Predict Outcome in Trauma-Informed Treatment of Intimate Partner Aggression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taft, C.T.; Street, A.E.; Marshall, A.D.; Dowdall, D.J.; Riggs, D.S. Posttraumatic stress disorder, anger, and partner abuse among Vietnam combat veterans. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taft, C.T.; Weatherill, R.P.; Woodward, H.E.; Pinto, L.A.; Watkins, L.E.; Miller, M.W.; Dekel, R. Intimate Partner and General Aggression Perpetration Among Combat Veterans Presenting to a Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Clinic. Am. J. Orthopsychiat. 2009, 79, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teten, A.L.; Schumacher, J.A.; Taft, C.T.; Stanley, M.A.; Kent, T.A.; Bailey, S.D.; Dunn, N.J.; White, D.L. Intimate Partner Aggression Perpetrated and Sustained by Male Afghanistan, Iraq, and Vietnam Veterans With and Without Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 1612–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sexton, M.B.; Davis, A.K.; Buchholz, K.R.; Winters, J.J.; Rauch, S.A.M.; Yzquibell, M.; Bonar, E.E.; Friday, S.; Chermack, S.T. Veterans with recent substance use and aggression: PTSD, substance use, and social network behaviors. Psychol. Trauma-US 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, N.H.; Duke, A.A.; Overstreet, N.M.; Swan, S.C.; Sullivan, T.P. Intimate partner aggression-related shame and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: The moderating role of substance use problems. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, N.H.; Duke, A.A.; Sullivan, T.P. Evidence for a curvilinear dose-response relationship between avoidance coping and drug use problems among women who experience intimate partner violence. Anxiety Stress Coping 2014, 27, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunradi, C.B.; Ames, G.M.; Duke, M. The Relationship of Alcohol Problems to the Risk for Unidirectional and Bidirectional Intimate Partner Violence among a Sample of Blue-Collar Couples. Violence Vict. 2011, 26, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckhardt, C.I. Effects of alcohol intoxication on anger experience and expression among partner assaultive men. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fals-Stewart, W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2003, 71, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, T.M.; Elkins, S.R.; McNulty, J.K.; Kivisto, A.J.; Handsel, V.A. Alcohol Use and Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among College Students: Assessing the Temporal Association Using Electronic Diary Technology. Psychol. Violence 2011, 1, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.H.; Homish, G.G.; Leonard, K.E.; Cornelius, J.R. Intimate Partner Violence and Specific Substance Use Disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012, 26, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witte, T.H.; Kopkin, M.R.; Hollis, S.D. Is It Dating Violence or Just “Drunken Behavior”? Judgments of Intimate Partner Violence When the Perpetrator Is Under the Influence of Alcohol. Subst. Use Misuse 2015, 50, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, A.M.; Edwards, K.M. Perpetrators’ and Victims’ Attributions for IPV: A Critical Review of the Literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 18, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Shortt, J.W.; Kim, H.K. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In Family Psychology: The Art of the Science; Pinsof, W.M., Lebow, J.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Kim, H.K. Typological Approaches to Violence in Couples: A Critique and Alternative Conceptual Approach. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.P. Patriarchal Terrorism and Common Couple Violence—2 Forms of Violence against Women. J. Marriage Fam. 1995, 57, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P. Domestic violence: The intersection of gender and control. In Gender Violence: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 2nd ed.; O’Toole, L.L., Schiffman, J.R., Edwards, M.L.K., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, E.J. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2007, 11, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Arriaga, X.B.; Agnew, C.R. Running on empty: Measuring psychological dependence in close relationships lacking satisfaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2018, 35, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Schkeryantz, E.L. Intimate Relationships and Personal Distress: The Invisible Harm of Psychological Aggression. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 41, 1332–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, R.B.; Malley-Morrison, K. Emotional commitment, normative acceptability, and attributions for abusive partner behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 1998, 13, 682–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Arias, I.; Beach, S.R.H.; Brody, G.; Roman, P. Excuses, excuses: Accounting for the effects of partner violence on marital satisfaction and stability. Violence Vict. 1995, 10, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, K.C.; Burton, S.; Porter, L. Predicting the intentions of women in domestic violence shelters to return to partners: Does forgiveness play a role? J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Agnew, C.R.; Arriaga, X.B. The investment model of commitment processes. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology; Volume 2; Van Lange, P.A.M., Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfriend, W.; Agnew, C.R. Sunken Costs and Desired Plans: Examining Different Types of Investments in Close Relationships. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 2008, 34, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, K.H. The ties that bind women to violent premarital relationships: Processes of seduction and entrapment. In Family Violence from a Communication Perspective; Cahn, D.D., Lloyd, S.A., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gelles, R. Through a sociological lens: Social structure and family violence. In Current Controversies on Family Violence; Loseke, R.J.G.D.R., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash, R.E.; Dobash, R. Violence against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.F.M.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I.; Arnoso, A.; Elgorriaga, E. Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Adaptation to Basque Population and Sexism as a Risk Factor of Dating Violence. Span. J. Psychol. 2016, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondon, M.B. From Marianism to terrorism: The many faces of violence against women in Latin America. Arch. Women Ment. Health 2003, 6, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakar, R.; Zakar, M.Z.; Kraemer, A. Men’s Beliefs and Attitudes toward Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Pakistan. Violence Against Women 2013, 19, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentich, M. Rape revisited: Sexual violence against women in the former Yugoslavia. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 1994, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Obeid, N.; Chang, D.F.; Ginges, J. Beliefs about Wife Beating: An Exploratory Study with Lebanese Students. Violence Against Women 2010, 16, 691–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendixen, M.; Henriksen, M.; Nostdahl, R.K. Attitudes toward Rape and Attribution of Responsibility to Rape Victims in A Norwegian Community Sample. Nord. Psychol. 2014, 66, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, E.H. Rethinking Patriarchy, Culture and Masculinity: Transnational Narratives of Gender Violence and Human Rights Advocacy. J. Int. Women Stud. 2015, 16, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Emery, C. Marital power, conflict, norm consensus, and marital violence in a nationally representative sample of Korean couples. J. Interpers. Violence 2003, 18, 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, R.; Otis, M.D. Gender Equality, Patriarchal Cultural Norms, and Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence: Comparison of Male University Students in Asian and European Cultural Contexts. Violence Against Women 2017, 23, 1076–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihama, M. A web in the patriarchal clan system—Tactics of intimate partners in the Japanese sociocultural context. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 1236–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capezza, N.M.; Arriaga, X.B. You Can Degrade but You Can’t Hit: Differences in Perceptions of Psychological Versus Physical Aggression. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2008, 25, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, B.E.; Worden, A.P. Attitudes and beliefs about domestic violence: Results of a public opinion survey—I. Definitions of domestic violence, criminal domestic violence, and prevalence. J. Interpers. Violence 2005, 20, 1197–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorenson, S.B.; Taylor, C.A. Female aggression toward male intimate partners: An examination of social norms in a community-based sample. Psychol. Women Quart. 2005, 29, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga, X.B.; Capezza, N.M.; Goodfriend, W.; Rayl, E.S.; Sands, K.J. Individual Well-Being and Relationship Maintenance at Odds: The Unexpected Perils of Maintaining a Relationship With an Aggressive Partner. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2013, 4, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Martz, J.M. Remaining in an Abusive Relationship—An Investment Model Analysis of Nonvoluntary Dependence. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B 1995, 21, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goodfriend, W.; Arriaga, X.B. Cognitive Reframing of Intimate Partner Aggression: Social and Contextual Influences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112464

Goodfriend W, Arriaga XB. Cognitive Reframing of Intimate Partner Aggression: Social and Contextual Influences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(11):2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112464

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoodfriend, Wind, and Ximena B. Arriaga. 2018. "Cognitive Reframing of Intimate Partner Aggression: Social and Contextual Influences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 11: 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112464

APA StyleGoodfriend, W., & Arriaga, X. B. (2018). Cognitive Reframing of Intimate Partner Aggression: Social and Contextual Influences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2464. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112464