Sensitizing Black Adult and Youth Consumers to Targeted Food Marketing Tactics in Their Environments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

2.3.1. Pre-Sensitization Focus Group Protocol

2.3.2. Sensitization Procedure

2.3.3. Post-Sensitization Focus Group Protocol

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Themes

3.2.1. Seeing the Marketer’s Perspective

It’s about Demand

Consumers Choose

3.2.2. Respect for the Community

Marketers are Setting us up for Failure

Marketers’ Assumptions are Wrong

3.2.3. Food Environments as a Social Justice Issue

No One is Watching the Door

I Didn’t Realize

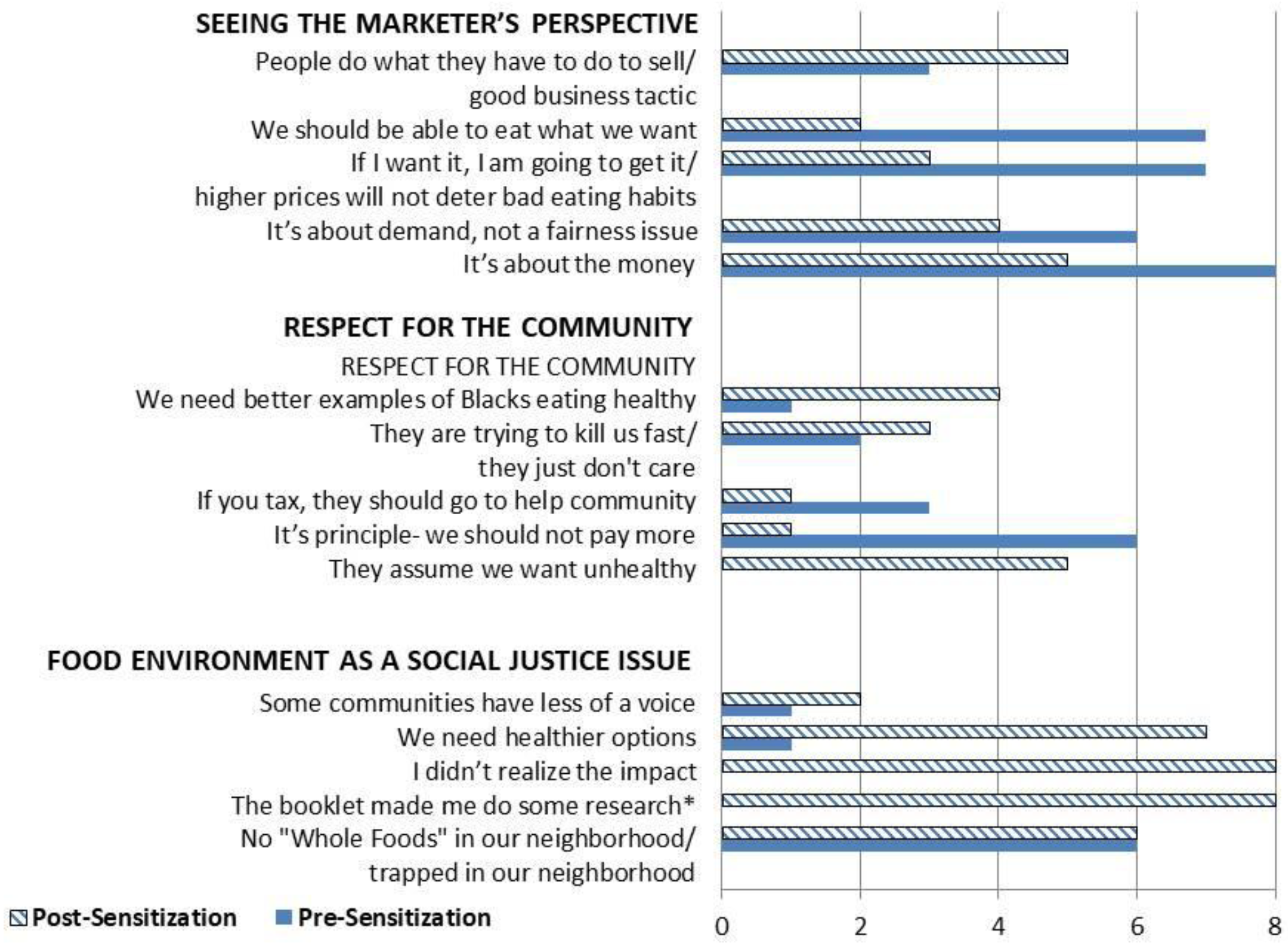

3.2.4. Direct Assessment of Responses to the Booklet and Relative Theme Prominence Pre- and Post-Sensitization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Agriculture. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (Advisory Report) to the Secretaries of the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Agriculture (USDA). Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Harris, J.L.; Pomeranz, J.L.; Lobstein, T.; Brownell, K.D. A crisis in the marketplace: How food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2009, 30, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestle, M.; Jacobson, M. Halting the obesity epidemic: A public health policy approach. Public Health Rep. 2000, 115, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, C.; Carroll, M.; Lawman, H.; Fryar, C.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Kit, B.; Flegal, K. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 through 2013–2014. JAMA 2016, 315, 2292–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegal, K.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Carroll, M.; Fryar, C.; Ogden, C. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016, 315, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. CDC Vital Signs, African American Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Harris, J.L.; Shehan, C.; Gross, R.; Kumanyika, S.; Lassiter, V.; Ramirez, A.G.; Gallion, K. Food Advertising Targeted to Hispanic and Black Youth: Contributing to Health Disparities; UCONN Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity: Storrs, CT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grier, S.A.; Kumanyika, S.K. The context for choice: Health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. Amer. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 1616–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J.D.; Crockett, D.; Harrison, R.L.; Thomas, K.D. The role of food culture and marketing activity in health disparities. Prev. Med. 2012, 55, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grier, S.A.; Kumanyika, S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 349–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmedo, P.C.; Dorfman, L.; Garza, S.; Murphy, E.; Freudenberg, N. Countermarketing alcohol and unhealthy food: An effective strategy for preventing noncommunicable diseases? Lessons Tobacco. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Challenges and Opportunities for Change in Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Workshop Summary; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.L.; Graff, S.K. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: Implications of psychological research for first amendment law. Amer. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.L.; Haraghey, K.S.; Choi, Y.; Fleming-Milici, F. Parents’ Attitudes about Food Marketing to Children: 2012 to 2015; UCONN Rudd Center for food policy and obesity: Storrs, CT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grier, S.A.; Lassiter, V. Understanding Community Perspectives: A Step Towards Achieving Food Marketing Equity. In Advances in Communication Research to Reduce Childhood Obesity; Williams, J.D., Pasch, K.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, USA, 2013; pp. 343–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kamberelis, G.; Dimitriadis, G. Focus Groups: Contingent Articulations of Pedagogy, Politics, and Inquiry. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Community Health Status Indicators; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Morgan, D. Focus groups. Annu. Rev. Sociology 1996, 22, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Cooper-Martin, E. Ethics and target marketing: The role of product harm and consumer vulnerability. J. Marketing 1997, 61, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, R.M. Food for Thought. A Mixed-Methods Media Literacy Intervention on Food Marketing Dissertation; University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lobstein, T.; Brinsden, H.; Landon, J.; Kraak, V.; Musicus, A.; Macmullan, J. INFORMAS and advocacy for public health nutrition and obesity prevention. Obesity Rev. 2013, 14, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Askew, W.L.; Fisher, R.; Henderson, K.; Schwartz, M. Attitudes of african american advocates toward childhood obesity. Ethnicity and Dis. 2011, 21, 268. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, D.M.K.K. Teenage exposure to cigarette advertising in popular consumer magazines. J. Public Policy Mark 2000, 19, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.J.; Williams, J.D.; Qualls, W.J. Target marketing of tobacco and alcohol-related products to ethnic minority groups in the United States. Ethn. Dis. 1996, 6, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hawkes, C.; Smith, T.G.; Jewell, J.; Wardle, J.; Hammond, R.A.; Friel, S.; Kain, J. Smart food policies for obesity prevention, smart food policies for obesity prevention. Lancet 2015, 385, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adult Focus Groups | Youth Focus Groups |

|---|---|

Scenario Described (Promotion): This past summer, (Fast Food Company) sponsored a national tour, visiting six U.S. cities. Headlined by a (Popular R and B Singer/TV Actor Name).

| Scenario Described (Promotion): (Popular Rap Artist Name) will perform for Black teens in an exclusive, free concert sponsored by (Large Beverage Company)

|

Scenario Described (Place): Supermarkets are not always located in every neighborhood.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Place): Last year the Los angeles city council passed a new law to prohibit the opening of new fast food restaurants for one year in South Los Angeles neighborhoods.

| Scenario Described (Place): A survey of food prices found that the stores near the mostly Black high schools had higher prices for items like potato chips than stores near white schools.

|

Scenario Described (Price): Several states have a specific sales tax on soft drinks and other sugar-sweetened beverages. Such taxes apply to sports drinks, sweetened teas, fruit drinks, but do not apply to diet sodas or 100% fruit juice.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Productand Promotion): A new research report summarizes Black Americans’ food-related attitudes and behaviors. The report states that Black Americans have less interest in healthy eating relative to the population as a whole, and that companies can profit by targeting Black households for products like chips and soda, which other households are eating less of.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Product): Research shows that Black consumers often add sugar to their tea when it is already sweetened. A fast food company decides to offer a sweeter version of the tea at locations in Black areas and promote regular tea in other areas.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Product): Products can be designed to appeal to different types of consumers, for example cigarette brands, flavors, and packages have been designed to appeal to youth.

| Scenario Described (Product): Products can be designed to appeal to different types of consumers, for example cigarette brands, flavors, and packages have been designed to appeal to youth (people your age).

|

Scenario Described (Promotion):(Large Beverage Company) unveiled the (Phone App Name) for mobile phones, to create a “community-to-go” and to interact with its “mostly African-American youth target audience”.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Place/Promotion): The number of outdoor ads has been found to greater in primarily African American areas

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Price/Place): A survey of food prices found that the stores near the mostly Black high schools had higher prices for items like potato chips than stores near white schools.

| (Presented earlier in youth group) |

Scenario Described (Promotion): TV and radio commercials are designed to appeal to different types of consumers. For example, commercials are designed to appeal to different racial or ethnic groups.

| Same as for adult groups |

Scenario Described (Promotion): Marketing agencies often use popular artists’ songs to promote specific product brands for cars, clothes, beverages, etc.

| Same as for adult groups |

| Variable | Durham Participants | Prince George’s County Participants |

|---|---|---|

| n = 10 * | n = 15 | |

| Age | ||

| 19 to 35 years | 7 (70%) | 3 (20%) |

| 36 to 65 years | 3 (30%) | 12 (80%) |

| Female Male | 8 (80%) 2 (20%) | 12 (80%) 3 (20%) |

| Education | ||

| Some college or less | 8 (80%) | 7 (47%) |

| College grad or more | 2 (20%) | 8 (53%) |

| Married/living with partner | 1 (10%) | 8 (53%) |

| Employment | ||

| Full or part-time | 5 (50%) | 11 (79) ** |

| Not employed, retired/student | 5 (50%) | 3 (21%) |

| Primary household shopper | 6 (60%) | 11 (73%) |

| Site, Gender, and Age Group | Comments |

|---|---|

| Durham, Adults | (General Reaction) “And as I read the book… Then later on I was looking in the different communities… and seeing that a lot of the advertisement, the posting, the pricing, you know, everything that was in the book was just like it was in real life.” |

| Durham, Boys | (General Reaction) “I just feel like it’s surprising out here you try to, you know, companies try to get in where they fit in, I guess. From a company point of view I could say it’s a very smart way to market, you know, to find out what people like and then try to persuade them through the things that they like, but just on the other hand I just feel like there’s something about it that’s shady.” |

| Durham, Girls | (In reaction to Promotion section) “like every time (TV CHANNEL aimed at Black audience) a commercial it’s for (FAST FOOD RESTAURANT). So that makes—that makes sense. But the way that they do it you really don’t notice it. You know? Because you’re just watching TV. You’re like oh, that looks good… So it’s—it’s really slick.… That’s interesting.” |

| Prince George’s County, Adults | (In reaction to Price section) “What stuck out to me was the value meals, you know, supersizing and things like that. And actually it made me, the source, I went on the internet and looked it up, and it was like a 14-page report on it. And it was just amazing to me how they, they market”. |

| Prince George’s County, Boys | (In reaction to Place section) “I mean not just in the book but I didn’t really know that not everybody had a supermarket. I thought everyone did. I didn’t—that was like I don’t know.” |

| Prince George’s County, Girls | (In reaction to Place section) “the smaller-the smallest store is carrying, um, less fresh produce. I never really thought about that, but it actually makes more sense now.” |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isselmann DiSantis, K.; Kumanyika, S.; Carter-Edwards, L.; Rohm Young, D.; Grier, S.A.; Lassiter, V. Sensitizing Black Adult and Youth Consumers to Targeted Food Marketing Tactics in Their Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111316

Isselmann DiSantis K, Kumanyika S, Carter-Edwards L, Rohm Young D, Grier SA, Lassiter V. Sensitizing Black Adult and Youth Consumers to Targeted Food Marketing Tactics in Their Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(11):1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111316

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsselmann DiSantis, Katherine, Shiriki Kumanyika, Lori Carter-Edwards, Deborah Rohm Young, Sonya A. Grier, and Vikki Lassiter. 2017. "Sensitizing Black Adult and Youth Consumers to Targeted Food Marketing Tactics in Their Environments" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 11: 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111316

APA StyleIsselmann DiSantis, K., Kumanyika, S., Carter-Edwards, L., Rohm Young, D., Grier, S. A., & Lassiter, V. (2017). Sensitizing Black Adult and Youth Consumers to Targeted Food Marketing Tactics in Their Environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1316. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111316