1. Introduction

Overweight and obesity have increased worldwide at an alarming rate in recent decades, affecting people irrespective of age or socioeconomic status [

1]. Although obesity prevalence seems to have reached a plateau in several high-income countries, it continues to grow in Latin American countries, which are undergoing rapid nutritional transitions [

2]. In the specific case of Chile, the prevalence of adult obesity was 23.2% in 2015 [

3], whereas 34.3% of adolescents have been reported to be overweight (25.1%) or obese (9.2%) [

4]. Although several factors are involved in obesity, changes in eating behavior caused by the global nutrition transition have been recognized as major determinants of the obesity epidemic [

5]. This transition is characterized by decreased consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables, and increased consumption of processed products with high sugar, fat, and salt content [

6]. For this reason, interventions aimed at shifting eating behavior have been identified as top priorities for reducing the burden of obesity and non-communicable diseases [

7].

In particular, adolescent eating behaviors are influenced by several interrelated factors, and family has been reported to be one of the main determinants [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Parents can shape their children’s eating behavior by providing (un)healthful foods at home [

9,

12,

13,

14], modeling food choices [

8], encouraging healthy eating [

9], and promoting family meals [

9,

13]. Outcomes related to parental modeling can be both positive and negative, depending on behaviors modeled by the parents and behaviors copied by their children [

15]. At the same time, although mothers and fathers influence their children’s eating behavior [

16], parental influence has been reported to vary widely [

17,

18]. Hebestreit et al. [

13] found that mothers exert a positive influence on their children’s food consumption because they are more likely to adhere to dietary guidelines, whereas fathers primarily influence their children’s intake of unhealthy foods. Similar findings have been reported by Tabbakc and Freeland-Graves [

19]. In addition, mothers not only influence their children’s food consumption, but also that of their husbands [

18].

The relationship between food and family plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of adolescent obesity [

20,

21]. There is evidence of a positive association between frequent family meals and healthy diets in adolescents [

9,

13,

22,

23], as well as higher diet quality scores based on the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) in adolescents [

24] and adults [

25]. Higher HEI scores have been associated with a greater frequency of cooking and eating at home, and negatively associated with a higher frequency of eating out [

25]. Nevertheless, when healthful parenting practices are low, family meals do not seem to have a positive association with healthy food intake [

9].

The affective dimension of meals as a moment of family unity is an important component of the role of food within families [

21,

26,

27]. Family meals prove to be an important ritual for interaction, preserving relationship closeness, resolving conflicts, expressing affection, providing emotional support, and nurturing harmony and function [

10,

26,

27]. All of these components have been associated with healthier eating as well as a lower likelihood of obesity or being overweight among adolescents. In addition, family meals are also important for the well-being of adolescents [

22,

28].

Subjective well-being is a multidimensional category of phenomena involving emotional responses, positive and negative affect, and global judgments of life satisfaction in different domains [

29]. Satisfaction with food-related life is defined as a person’s overall assessment regarding their food and eating habits [

30]. Recent studies suggest that satisfaction in the food domain is positively correlated with overall life satisfaction, both in adults and in emerging adults [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. In addition, higher levels of life satisfaction and satisfaction with food-related life have been positively associated with better eating habits [

32,

33], lower prevalence of being overweight or obese [

32,

33], and greater frequency and importance assigned to family meals [

32,

33,

34,

35].

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have assessed the relationship between these variables while studying different family members simultaneously. In parallel, existing research on food parenting practices and family meals has predominantly focused on mothers [

17,

36,

37]. However, fathers also play an important role in their children’s eating habits due to women’s rising participation in the formal labor market. Although the engagement level of fathers in childrearing has increased over the decades [

18,

37], existing research on diet quality with samples of mother–father–children triads is still scarce [

17,

38] and limited to developed countries [

38].

Although the relationship between mothers and their children’s dietary intake has been extensively studied in the literature [

17,

37,

38], few studies have examined mother–father intakes. Furthermore, even fewer studies have analyzed diet quality in family member triads [

17,

38]. In particular, no research has been published examining triads in developing countries and dealing with adolescents over 12 years of age [

38]. In this context, the objectives of the present study were: (i) to assess diet quality, eating habits, satisfaction with life, family life and food-related life in mother–father–adolescent triads and (ii) to identify family profiles according to family member diet quality.

3. Results

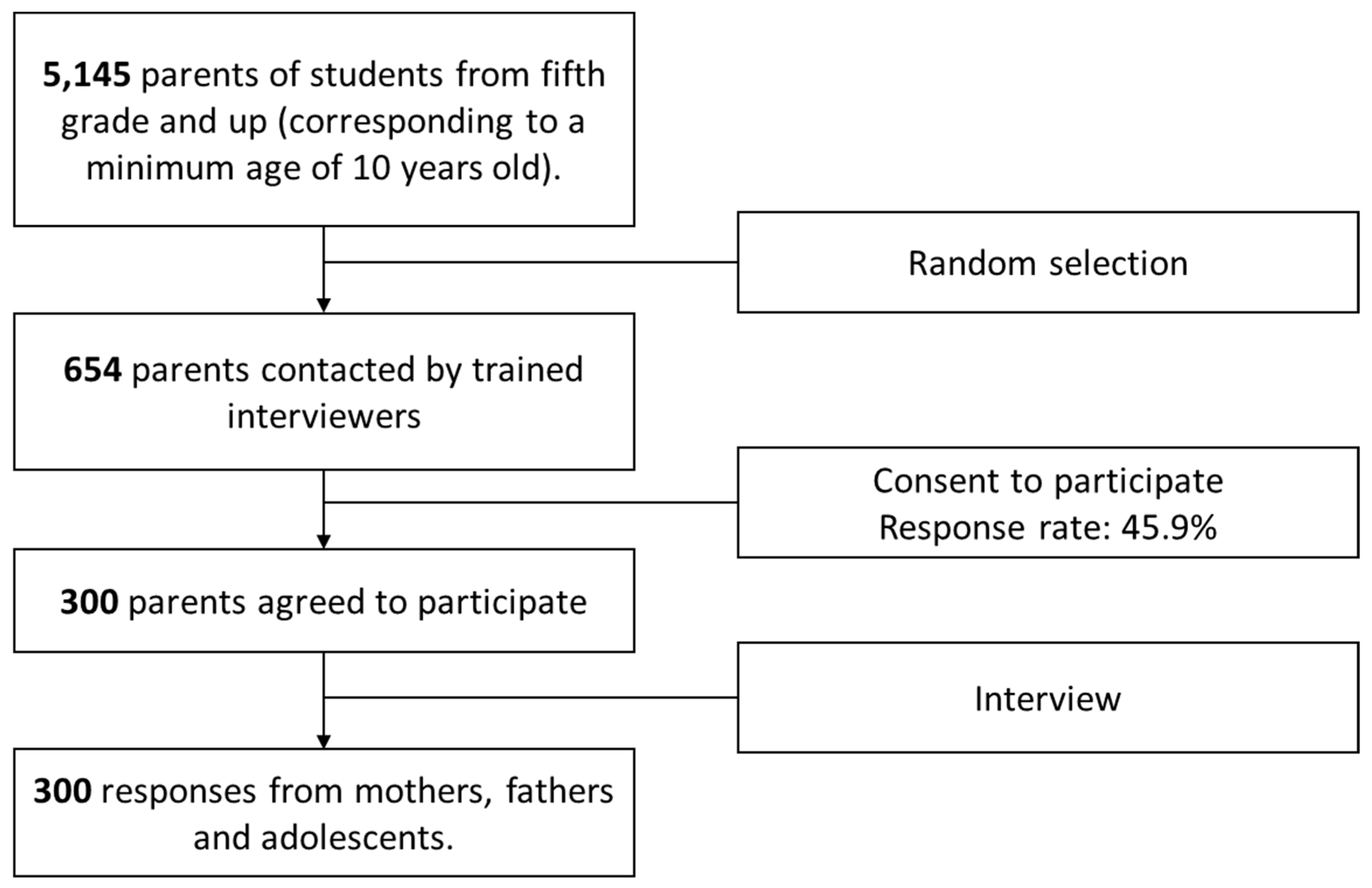

3.1. Study Participants

A total of 300 two-parent families participated in the study. Only one adolescent per family was interviewed, resulting in a total of 300 responses for mothers, fathers, and adolescents.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample, the three subsample compositions according to body mass indexes following the criteria of the World Health Organization [

1] for mothers and fathers and the criteria of the World Health Organization [

52] and the Technical Norm of Nutritional Evaluation of children from five to 19 years old of the Ministry of Health of Chile [

53].

Table 1 also includes family eating habits, monthly expenditure on food, and the person responsible for deciding what to eat and what food to purchase for the household.

3.2. Diet Quality, Eating Habits, and Nutritional Knowledge

The average AHEI score for the family members was similar, and denoted diets that required changes: 64.5 (SD = 14.3) for mothers, 58.9 (SD = 14.6) for fathers, and 62.0 (SD = 15.0) for adolescents. The AHEI scores of the family members were significantly correlated, but the highest correlation coefficient was found for the AHEI scores of mothers and adolescents. The Pearson correlation coefficients corresponded to 0.447 (p < 0.01) for mothers and adolescents, 0.308 (p < 0.01) for fathers and mothers, and 0.215 (p < 0.01) for fathers and adolescents.

According to the cut-off proposed by Kennedy et al. [

39], the minority of family members had a healthy diet that did not require changes. In the case of mothers, 14.7% had a healthy diet, 69.7% had diets that required changes, and 15.7% had an unhealthy diet. Regarding fathers, only 5.3% had a healthy diet, 69.7% required changes, and 25.0% had an unhealthy diet. Similarly, 11.3% of the children had a healthy diet, 67.3% required changes, and 21.3% had an unhealthy diet. The proportion of participants who had a healthy diet was significantly higher in the subsample of mothers than in the subsamples of fathers and adolescents (

p ≤ 0.001). In addition, the proportion of participants who had an unhealthy diet was significantly higher in the subsample of fathers than in the mother and children subsamples (

p ≤ 0.001).

Table 2 shows the consumption frequency of the food categories included in the AHEI for mothers, fathers and adolescents. As can be seen, mothers consumed fruit and vegetables significantly more often than fathers and adolescents. Fathers showed the highest consumption frequency of sausages and cold meats, whereas adolescents showed the highest consumption frequency of cereals and derivatives, milk and dairy products, and sweets. Fathers and children showed a higher consumption frequency of soda than mothers. Family members did not significantly differ in their consumption frequency of meat and legumes (

p > 0.1).

Average nutrition knowledge on dietary recommendations related to nutrient intake was 69.1% for mothers and 66.0% for fathers. Regarding average nutrition knowledge on dietary recommendations related to food intake, it was 65.3% for mothers and 64.9% for fathers. In addition, 33.7% of the mothers considered food to be considerably important for their well-being and 31.3% considered it to be very important. For fathers, these percentages were 35.0% and 31.3%, respectively. In the case of adolescents, 35.0% considered food to be very important for their well-being and 34.7% considered it to be considerably important.

3.3. Reliability and Validity of the Satisfaction Scales

Reliability and validity of the satisfaction scales were evaluated using CFA. Results indicated that the SWLS, SWFoL and SWFaL scales satisfied the composite reliability test (above 0.7) for the subsamples of mothers, fathers, and children. The scales also satisfied the AVE values (higher than 0.5) in the three subsamples (mothers, fathers, and adolescents) (

Table 3). The value of the squared correlation between the SWLS and SWFoL was lower than the AVE of the scales, which verified the discriminant validity between the constructs in the three subsamples. The discriminant validity between SWLS and SWFaL and between SWFoL and SWFaL was also verified in the three subsamples [

50].

All the factor loadings from the SWFoL, SWFaL, and SWLS were over 0.58 and statistically significant in the three subsamples. Therefore convergent validity was shown for the three scales and the internal validity of the measurement models was adequate in the three subsamples.

Regarding the CFA with correlated latent constructs for each family member, the models had a good fit of the data in the subsample of mothers (RMSEA = 0.057, CFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.94, AGFI = 0.92), fathers (RMSEA = 0.059, CFI = 0.99, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.90), and children (RMSEA = 0.052, CFI = 0.99 GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.93). The correlation values between SWLS, SWFaL, and SWFoL were positive and significant in the three subsamples (

Table 3).

Regarding CFA with correlated latent constructs between the SWLS, SWFoL, and SWFaL among the three family members, the CFA model showed a good fit of the data for the SWFoL (RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.91). Correlation values between the SWFoL for mothers, fathers and adolescents were positive and significant (

Table 4). The CFA model also showed a good fit of the data for the SWFaL (RMSEA = 0.056, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.94, AGFI = 0.92). The correlation values between the SWFaL of mothers, fathers, and adolescents were positive, but only significant between mothers and fathers and between mothers and adolescents. In the same way, the CFA model also showed a good fit of the data for the SWL scale (RMSEA = 0.055, CFI = 0.98, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.91). Correlation values between mothers, fathers, and adolescents were positive, but again only significant between mothers and fathers and between mothers and adolescents. Therefore, the results indicate that adolescents’ life satisfaction, satisfaction with food-related life and satisfaction with family life were more strongly correlated with those of their mothers than with those of their fathers. In parallel, overall life satisfaction and satisfaction in the family and food domains were positively correlated for both parents.

Table 5 shows the mean SWLS, SWFoL, and SWFaL scores for mothers, fathers, and children. The AHEI was significantly and positively correlated with SWLS, SWFoL, and SWFaL for mothers and fathers, whereas in the case of adolescents, AHEI scores were only significantly correlated with SWLS and SWFoL. Correlation coefficients between AHEI and satisfaction scores were higher for mothers than for fathers and children. In particular, the highest coefficients were found for the correlation between AHEI and SWFoL for mothers.

3.4. Profiles of Families with Different Diet Quality

Cluster analysis identified three groups of families with different diet qualities. Families in Group 1 (39.3% of families) were characterized by the lowest AHEI scores for all family members, indicating the lowest diet quality (

Table 6). The average AHEI scores corresponded to unhealthy diets for adolescents and diets that required changes for both parents. Families in Group 2 showed the highest AHEI average scores, which corresponded to healthy diets for mothers and adolescents and to diets that required changes for fathers. Finally, families in Group 3 were characterized by intermediate average AHEI scores that corresponded to diets that required changes for all family members. Within Group 1, the average AHEI score for mothers (

p ≤ 0.001) and fathers (

p ≤ 0.05) were significantly higher than the average AHEI score for children. Within Groups 2 and 3, the average AHEI score for mothers and children (

p ≤ 0.001) were significantly higher than the average AHEI score for fathers.

Differences in diet quality between the three groups were explained by differences in the consumption frequency of most of the food groups, except for legumes in the three family members, and for meat in the subsamples of fathers and children (see

Supplementary Tables S1–S3). All family members in Group 1 had a lower consumption frequency of fruit, vegetables, cereals and derivatives, and milk and dairy products than those in Groups 2 and 3, and a higher consumption frequency of soft drinks with sugar, sausages, and cold meats. On the contrary, family members in Group 2 had the highest consumption frequency of healthy foods (fruit, vegetables, cereals and derivatives, milk and dairy products) and the lowest consumption frequency of unhealthy foods (soft drinks with sugar, sausages, and cold meats). In addition, family members in Group 2 had the highest average diet variety scores, followed by Group 3 and finally Group 1 (

p ≤ 0.001) (

Table 6).

Regarding eating habits, as shown in

Table 6, family members in Group 2 had breakfast together significantly more often than family members from Groups 1 and 3 (

p ≤ 0.001). They also had lunch together more often than family members from Group 1 (

p ≤ 0.05). Moreover, families in Group 2 ate homemade foods significantly more often per week than families in Group 1 and 3 (

p ≤ 0.05). On the contrary, families in Group 1 bought ready-to-eat foods and ate at fast food outlets (

p ≤ 0.05) significantly more often than families in Groups 2 and 3. The average monthly expenditure on food of families from Group 2 was significantly higher than that from Groups 1 and 3 (

p ≤ 0.05).

As shown in

Table 6, the average SWLS, SWFoL and SWFaL scores of mothers from Group 2 were significantly higher than in Groups 1 and 3 (

p ≤ 0.05). In addition, the average SWLS and SWFaL scores of fathers from Group 2 were significantly higher than in Groups 1 and 3 (

p ≤ 0.05).

Group 2 was composed of a greater proportion of families in which the mother decided what food to purchase for the household (

p ≤ 0.05), whereas Group 3 had a greater proportion of families in which the purchasing decisions were made by both parents (

Table 7). Group 1 had a higher proportion of obese mothers (

p ≤ 0.05). Additionally, Group 1 had greater proportions of mothers and children who consider food to be slightly important for their well-being (

p ≤ 0.05) and Group 2 had greater proportions of mothers and children who consider food to be completely important for their well-being.

Finally, no significant differences between the groups were found for the importance that fathers attached to food for their well-being, parental nutrition knowledge on dietary recommendations, the number of family members, number of children, number of siblings, sex of the interviewed adolescent, ethnic origin, the number of days a week they ate dinner together, number of days they ordered takeout food, the person responsible for purchasing foods, fathers and adolescents’ BMI, socioeconomic status, the place family members ate when they did not eat at home with their family, fathers’ scores on the SWFoL scale, and children’s scores on the SWLS, SWFoL, and SWFaL scales (p > 0.1).

5. Conclusions

Satisfaction with food-related life and satisfaction with family life have positive relationships with life satisfaction of different family members, and both life domains are positively related. Since the findings of this study show that better diet quality and more frequent family meals seem to be related to higher levels of satisfaction with life and family life in parents, studies on the relationship between food and family should not only consider diet-related variables, but also psychological variables. Similar research should be conducted on single-parent households with adolescent children. A special emphasis should be placed upon the detection of variables that lead some mothers to have unhealthy diets, provide an unhealthy food environment for their family, and introduce negative parental modeling to their adolescent children. In addition, future research should identify variables related to satisfaction with food-related life in fathers and adolescents.

The findings of the present study allow us to make suggestions about intervention methods to improve overall family diet quality according to each profile’s characteristics, as well as to enhance family member diet quality. In addition, the findings of this study suggest that interventions that aim to improve levels of satisfaction with food-related life and satisfaction with family life may also boost life satisfaction for all family members.