Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials

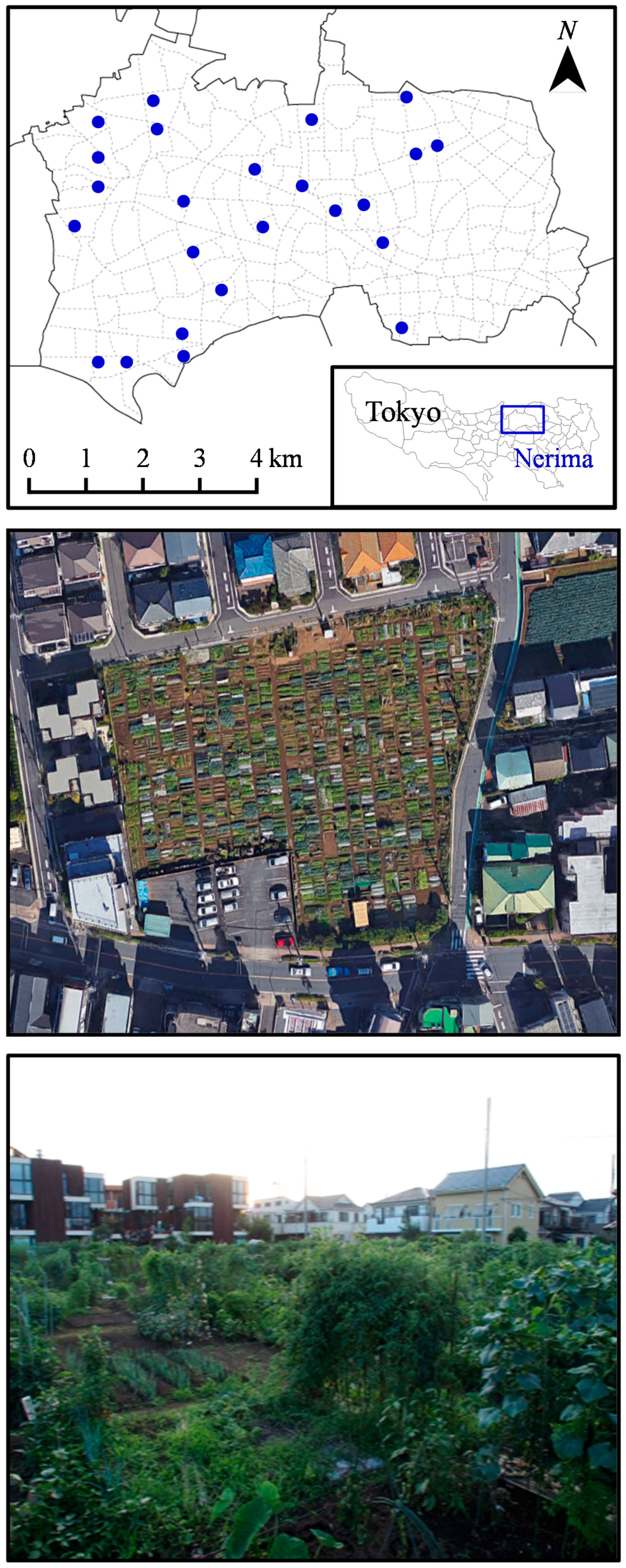

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Participants

2.3. Health Outcomes

- (1)

- Perceived general health was measured by a single question “How do you rate your health in general?” Responses were scored on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (Poor) to 5 (Excellent). This measure is known to be related to morbidity and mortality rates and is a strong predictor of health status [36,37]. In this section, gardeners were also asked to report how strongly they felt that their perceived general health was improved relative to before participating in gardening, which was scored on a four-point scale ranging from “No change” to “Strongly improved.”

- (2)

- Subjective health complaints were measured with a 10-item symptom checklist (feeling fatigue or tired, poor appetite, difficulty falling asleep, headache, constipation, lack of facial expression, hypothermia, catching a cold easily, out of breath during daily physical activities, feeling muscle weakness), which was modified from the Subjective Health Complaints Inventory [38]. The total number of health complaints was used as a measure of subjective health complaints, ranging from 0 to 10.

- (3)

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using self-reported height and weight. BMI is related to overall health and obesity, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity [39]. BMI values in excess of 25 and 30 are considered as overweight and obese, respectively.

- (4)

- Mental health was assessed using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire, which is the most extensively used self-report instrument for measuring common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression [40]. For each question, responses indicating distress score 1 and those indicating no or limited distress score 0. The scores across the 12 items were summed, ranging from 0 to 12.

- (5)

- Social cohesion was assessed with the Social Cohesion and Trust Scale [41]. This scale asked respondents how they agreed with statements about their neighbours. Responses of each of these items were scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (Disagree strongly) to 4 (Agree strongly). The scores across the five items were summed, ranging from 0 to 20.

2.4. Socio-Demographic and Lifestyle Variables

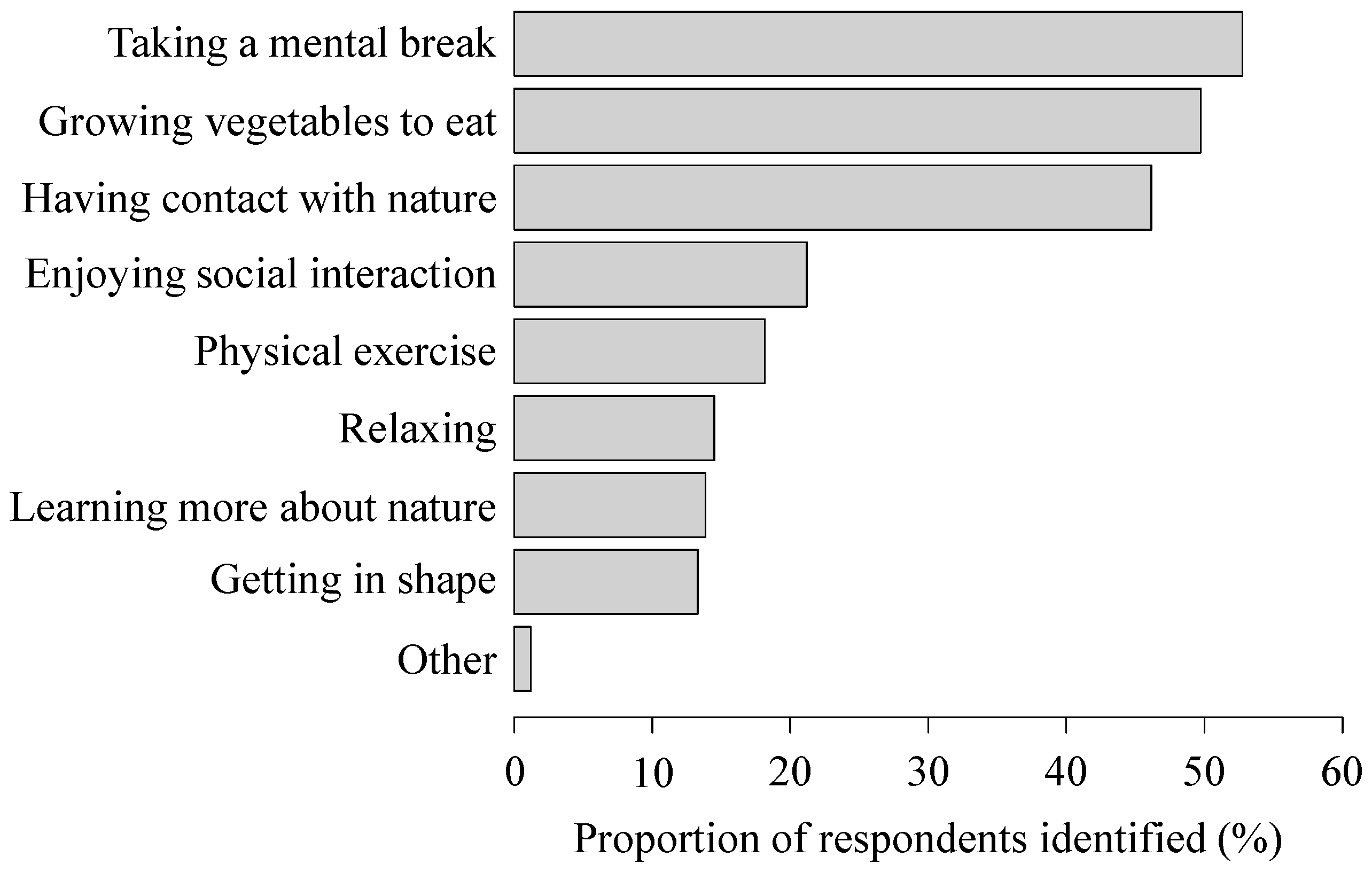

2.5. Motivation, Frequency and Duration of Gardening

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Description

3.2. Comparison of Gardeners and Non-Gardeners

3.3. Frequency and Duration of Gardening

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Database. Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/en/ (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Ewing, R.; Schmid, T.; Killingsworth, R.; Zlot, A.; Raudenbush, S. Relationship between urban sprawl and physical activity, obesity, and morbidity. Am. J. Health Promot. 2003, 18, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Lien, N.; Kumar, B.N.; Holmboe-Ottesen, G. Socio-demographic differences in food habits and preferences of school adolescents in Jiangsu Province, China. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peen, J.; Schoevers, R.A.; Beekman, A.T.; Dekker, J. The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 121, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederbogen, F.; Kirsch, P.; Haddad, L.; Streit, F.; Tost, H.; Schuch, P.; Wüst, S.; Pruessner, J.C.; Rietschel, M. City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature 2011, 474, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyemang, C. Rural and urban differences in blood pressure and hypertension in Ghana, West Africa. Public Health 2006, 120, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, V.; Mathur, P.; Deepa, R.; Deepa, M.; Shukla, D.K.; Menon, G.R.; Anand, K.; Desai, N.G.; Joshi, P.P.; Mahanta, J.; et al. Urban rural differences in prevalence of self-reported diabetes in India—The WHO–ICMR Indian NCD risk factor surveillance. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2008, 80, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romans, S.; Cohen, M.; Forte, T. Rates of depression and anxiety in urban and rural Canada. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2011, 46, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.S.; Bergmann, M.M.; Kroger, J.; Schienkiewitz, A.; Weikert, C.; Boeing, H. Healthy living is the best revenge: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 1355–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, C. Health and urban living. Science 2008, 319, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.; Kazmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Lin, B.B.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Dean, J.H.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Toward improved public health outcomes from urban nature. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCracken, D.S.; Allen, D.A.; Gow, A.J. Associations between urban greenspace and health-related quality of life in children. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanahan, D.F.; Bush, R.; Gaston, K.J.; Lin, B.B.; Dean, J.; Barber, E.; Fuller, R.A. Health benefits from nature experiences depend on dose. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardan, O.; Gozdyra, P.; Misic, B.; Moola, F.; Palmer, L.J.; Paus, T.; Berman, M.G. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N.; Balmford, A.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V.; Bradbury, R.B.; Amano, T. Seeing community for the trees: The links among contact with natural environments, community cohesion, and crime. BioScience 2016, 65, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.M.; Kaltenbach, A.; Szabo, A.; Bogar, S.; Nieto, F.J.; Malecki, K.M. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3453–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachowycz, K.; Jones, A.P. Greenspace and obesity: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e183–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Schellevis, F.G.; Groenewegen, P.P. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Yamaura, Y. Gardening is beneficial for health: A meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 5, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsley, J.Y.; Townsend, M.; Henderson-Wilson, C. Cultivating health and wellbeing: Members’ perceptions of the health benefits of a Port Melbourne community garden. Leis. Stud. 2009, 28, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Backx, K.; Clayton, D.A. Allotment gardening and other leisure activities for stress reduction and healthy aging. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.L.; Mercer, J.; Thirlaway, K.J.; Clayton, D.A. “Doing” gardening and “being” at the allotment site: Exploring the benefits of allotment gardening for stress reduction and healthy aging. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.J.; Pretty, J.; Griffin, M. A case-control study of the health and well-being benefits of allotment gardening. J. Public Health 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; van Winsum-Westra, M.; de Vries, S.; van Dillen, S.M. Allotment gardening and health: A comparative survey among allotment gardeners and their neighbors without an allotment. Environ. Health 2010, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milligan, C.; Gatrell, A.; Bingley, A. “Cultivating health”: Therapeutic landscapes and older people in northern England. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 1781–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.; Yeudall, F.; Taron, C.; Reynolds, J.; Skinner, A. Growing urban health: Community gardening in South-East Toronto. Health Promot. Int. 2007, 22, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, R.S.; Batista, D.S. Urban agriculture: The allotment gardens as structures of urban sustainability. In Advances in Landscape Architecture; Ozyavuc, M., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 457–512. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Fox-Kämper, R.; Keshavarz, N.; Benson, M.; Caputo, S.; Noori, S.; Voigt, A. Urban Allotment Gardens in Europe; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, D.; Ward, C. The Allotment. Its Landscape and Culture; Faber and Faber: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Forestry and Fisheries. Available online: http://www.maff.go.jp/j/nousin/nougyou/simin_noen/zyokyo.html (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo’s History, Geography, and Population. Available online: http://www.metro.tokyo.jp/ENGLISH/ABOUT/HISTORY/history03.htm (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Statistics Japan. Available online: http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jyutaku/index.htm (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- The Asian Foundation. Available online: http://healthbridge.ca/images/uploads/library/neighborhood_park_report.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Nerima City. Available online: http://www.city.nerima.tokyo.jp/index.html (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossey, J.M.; Shapiro, E. Self-rated health: A predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am. J. Public Health 1982, 72, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, H.R.; Ihlebaek, C.; Ursin, H. A scoring system for subjective health complaints (SHC). Scand. J. Public Health 1999, 27, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, D.J.; Frankel, S.J.; Nanchahal, K.; Peters, T.J.; Smith, G.D. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality: A 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, D. General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12); Nfer-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W.; Earls, F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 1997, 277, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, C.A.; Dopko, R.L.; Zelenski, J.M. The relationship between nature connectedness and happiness: A meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, E.K.; Zelenski, J.M. The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Richards, S.A. Testing ecological theory using the information-theoretic approach: Examples and cautionary results. Ecology 2005, 86, 2805–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genter, C.; Roberts, A.; Richardson, J.; Sheaff, M. The contribution of allotment gardening to health and wellbeing: A systematic review of the literature. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 78, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Koyanagi, T.F.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Urban residents’ perceptions of neighbourhood nature: Does the extinction of experience matter? Biol. Conserv. 2016, 203, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J. Extinction of experience: The loss of human-nature interactions. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2006, 174, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Available online: http://www.oecd.org (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- García, E.L.; Banegas, J.R.; Perez-Regadera, A.G.; Cabrera, R.H.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Social network and health-related quality of life in older adults: A population-based study in Spain. Qual. Life Res. 2005, 14, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmer, S.M.; Salisbury-Glennon, J.; Shannon, D.; Struempler, B. School gardens: An experiential learning approach for a nutrition education program to increase fruit and vegetable knowledge, preference, and consumption among second-grade students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, H.C.; Joshipura, K.J.; Jiang, R.; Hu, F.B.; Hunter, D.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, A.E.; Custers, M.H. Gardening promotes neuroendocrine and affective restoration from stress. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.T.; Hartig, T.; Patil, G.G.; Martinsen, E.W.; Kirkevold, M. A prospective study of group cohesiveness in therapeutic horticulture for clinical depression. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Richardson, E.A.; Shortt, N.K.; Pearce, J.R. Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Preventive Association of Life-Style Related Disease. Available online: http://www.seikatsusyukanbyo.com/statistics/ (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Japanese Association of Mental Health Services. Available online: http://www.npo-jam.org/library/materials/m_mhlw03.html (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Stott, I.; Soga, M.; Inger, R.; Gaston, K.J. Land sparing is crucial for urban ecosystem services. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2015, 13, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Yamaura, Y.; Aikoh, T.; Shoji, Y.; Kubo, T.; Gaston, K.J. Reducing the extinction of experience: Association between urban form and recreational use of public greenspace. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 143, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.B.; Philpott, S.M.; Jha, S. The future of urban agriculture and biodiversity-ecosystem services: Challenges and next steps. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Gardeners | Non-Gardeners | Statistical Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | Female | 52 | 31.9 | 92 | 58.2 | χ2 = 21.43, df = 1, p < 0.001 |

| Male | 111 | 68.1 | 66 | 41.8 | ||

| Household income | Less than ¥3,000,000 ($30,000) | 40 | 37.4 | 60 | 40.5 | χ2 = 3.58, df = 5, p = 0.61 |

| ¥3,010,000–5,000,000 | 25 | 23.4 | 38 | 25.7 | ||

| ¥5,010,000–7,000,000 | 13 | 12.1 | 22 | 14.9 | ||

| ¥7,010,000–10,000,000 | 17 | 15.9 | 13 | 8.8 | ||

| ¥10,010,000–15,000,000 | 9 | 8.4 | 10 | 6.8 | ||

| Over ¥15,000,000 | 3 | 2.8 | 5 | 3.4 | ||

| Employment status | Student | 3 | 1.9 | 5 | 3.2 | χ2 = 14.52, df = 7, p = 0.04 |

| Housewife/househusband | 30 | 19.2 | 37 | 23.7 | ||

| Irregular employee | 11 | 7.1 | 21 | 13.5 | ||

| Self-employed | 13 | 8.3 | 12 | 7.7 | ||

| Regular employee | 42 | 26.9 | 28 | 17.9 | ||

| Unemployed | 13 | 8.3 | 20 | 12.8 | ||

| Retiree | 43 | 27.6 | 28 | 17.9 | ||

| Others | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 3.2 | ||

| Smoking | Never | 140 | 87.5 | 138 | 87.3 | χ2 = 0.90, df = 3, p = 0.82 |

| Seldom | 3 | 1.9 | 2 | 1.3 | ||

| Sometimes | 15 | 9.4 | 14 | 8.9 | ||

| Often | 2 | 1.3 | 4 | 2.5 | ||

| Drinking alcohol | Never | 49 | 30.6 | 59 | 37.3 | χ2 = 8.57, df = 3, p = 0.04 |

| Seldom | 39 | 24.4 | 47 | 29.7 | ||

| Sometimes | 50 | 31.3 | 44 | 27.8 | ||

| Often | 22 | 13.8 | 8 | 5.1 | ||

| Vegetable intake | Seldom | 3 | 1.9 | 17 | 10.7 | χ2 = 35.22, df = 2, p < 0.001 |

| Sometimes | 71 | 44.1 | 104 | 65.4 | ||

| Often | 87 | 54.0 | 38 | 23.9 | ||

| Characteristics | Gardeners | Non-Gardeners | Statistical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Age (years) | 61.9 | 17.1 | 61.0 | 16.4 | F (1302) = 0.25, p = 0.62 |

| Nature relatedness | 3.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 0.6 | F (1319) = 0.31, p = 0.58 |

| Physical activity levels (days per week) | 3.9 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 3.3 | F (1306) = 0.001, p = 0.98 |

| Explanatory Variables | Perceived General Health | Subjective Health Complaints | BMI | General Mental Health | Social Cohesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (i) | |||||

| Age | −0.02 (0.01) ** | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.02) * |

| Gender (male) | 0.55 (0.27) * | −0.46 (0.19) * | 2.40 (0.38) *** | −0.28 (0.45) | 0.72 (0.61) |

| Nature relatedness | 0.50 (0.23) * | 0.08 (0.17) | −0.76 (0.33) * | 0.26 (0.35) | 0.43 (0.49) |

| Household income (¥3,010,000–5,000,000) | NA | −0.33 (0.24) | NA | −0.52 (0.51) | 0.28 (0.71) |

| Household income (¥5,010,000–7,000,000) | NA | −0.50 (0.31) | NA | −0.82 (0.65) | 0.56 (0.91) |

| Household income (¥7,010,000–10,000,000) | NA | −0.08 (0.34) | NA | −1.26 (0.71) | 0.12 (1.00) |

| Household income (¥10,010,000–15,000,000) | NA | −0.47 (0.45) | NA | −1.65 (0.95) | 2.4 (1.32) |

| Household income (over ¥15,000,000) | NA | 0.13 (0.54) | NA | −1.84 (1.12) | 1.76 (1.57) |

| Employment status (student) | 3.32 (1.38) | NA | NA | −3.42 (1.84) | NA |

| Employment status (housewife/househusband) | 0.06 (0.51) | NA | NA | 0.73 (0.70) | NA |

| Employment status (irregular employee) | 0.04 (0.53) | NA | NA | 0.25 (0.78) | NA |

| Employment status (self-employed) | 0.31 (0.51) | NA | NA | −0.71 (0.78) | NA |

| Employment status (unemployed) | −0.48 (0.56) | NA | NA | 0.74 (0.86) | NA |

| Employment status (retiree) | −0.46 (0.44) | NA | NA | 0.03 (0.73) | NA |

| Employment status (others) | 0.17 (0.94) | NA | NA | −1.45 (1.40) | NA |

| Frequency of smoking | −0.32 (0.18) | 0.16 (0.13) | 0.00 (0.26) | 0.56 (0.27) * | 0.65 (0.38) |

| Frequency of drinking alcohol | 0.04 (0.14) | 0.04 (0.10) | 0.10 (0.20) | 0.45 (0.21) * | 0.54 (0.29) |

| Frequency of vegetable intake | 0.81 (0.22) *** | −0.41 (0.16) ** | 0.12 (0.32) | −1.24 (0.34) *** | 0.51 (0.47) |

| Physical activity levels | 0.15 (0.06) ** | −0.06 (0.03) * | 0.00 (0.07) | −0.06 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.10) |

| Model (ii) | |||||

| Model (i) + Respondent type (gardener) | 1.40 (0.29) *** | −0.43 (0.21) * | 0.56 (0.39) | −0.91 (0.42) * | 1.57 (0.57) *** |

| Model (iii) | |||||

| Model (i) + Frequency of gardening (times per month) | 0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.03) | 0.08 (0.04) |

| Model (i) + Duration of gardening (monthly total minutes) | 0.06 (0.55) | −0.62 (0.32) | −0.04 (0.87) | −0.48 (0.64) | 0.96 (1.14) |

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soga, M.; Cox, D.T.C.; Yamaura, Y.; Gaston, K.J.; Kurisu, K.; Hanaki, K. Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010071

Soga M, Cox DTC, Yamaura Y, Gaston KJ, Kurisu K, Hanaki K. Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(1):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010071

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoga, Masashi, Daniel T. C. Cox, Yuichi Yamaura, Kevin J. Gaston, Kiyo Kurisu, and Keisuke Hanaki. 2017. "Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 1: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010071

APA StyleSoga, M., Cox, D. T. C., Yamaura, Y., Gaston, K. J., Kurisu, K., & Hanaki, K. (2017). Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14010071