A CALB-like Cold-Active Lipolytic Enzyme from Pseudonocardia antarctica: Expression, Biochemical Characterization, and AlphaFold-Guided Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

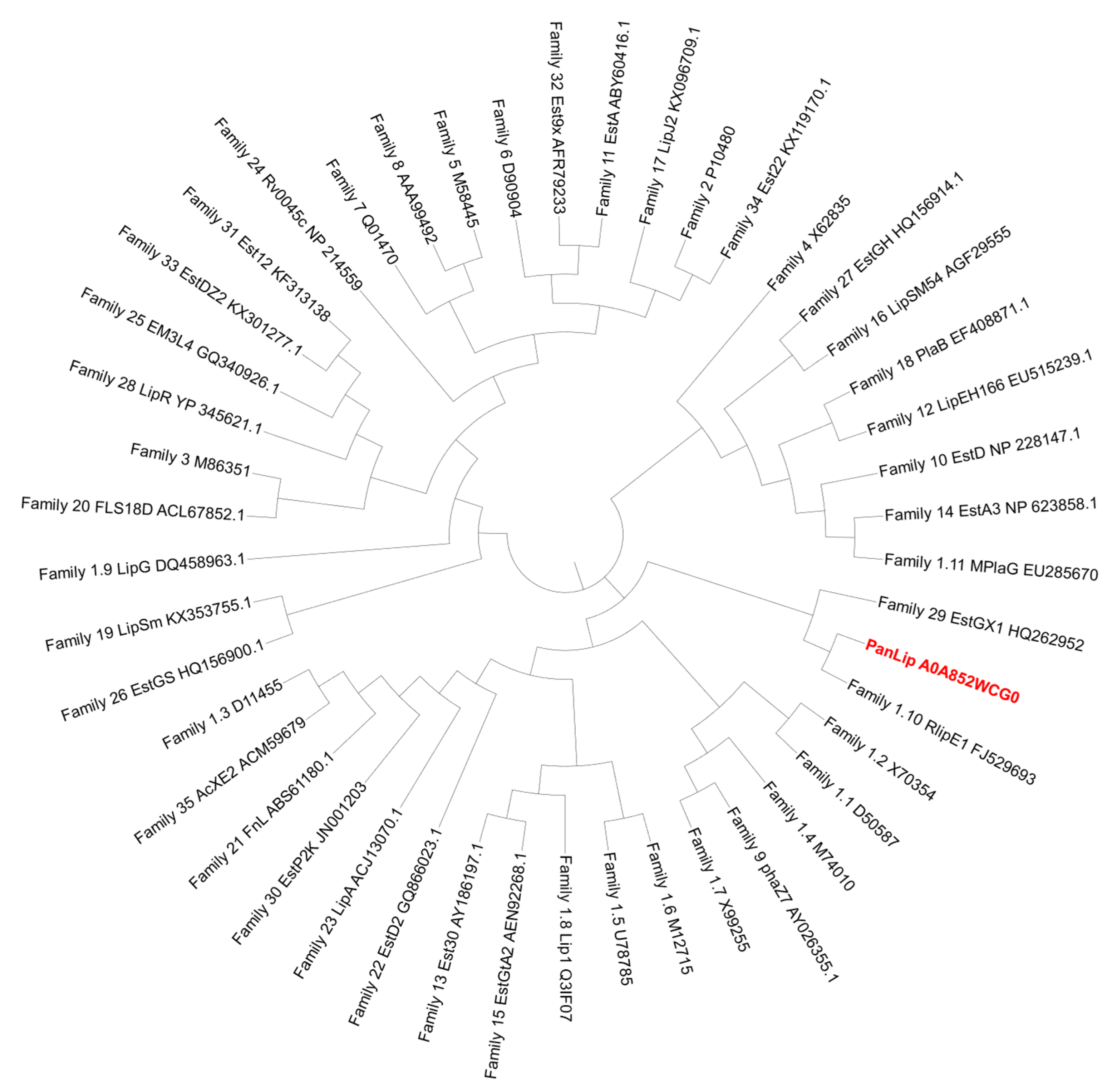

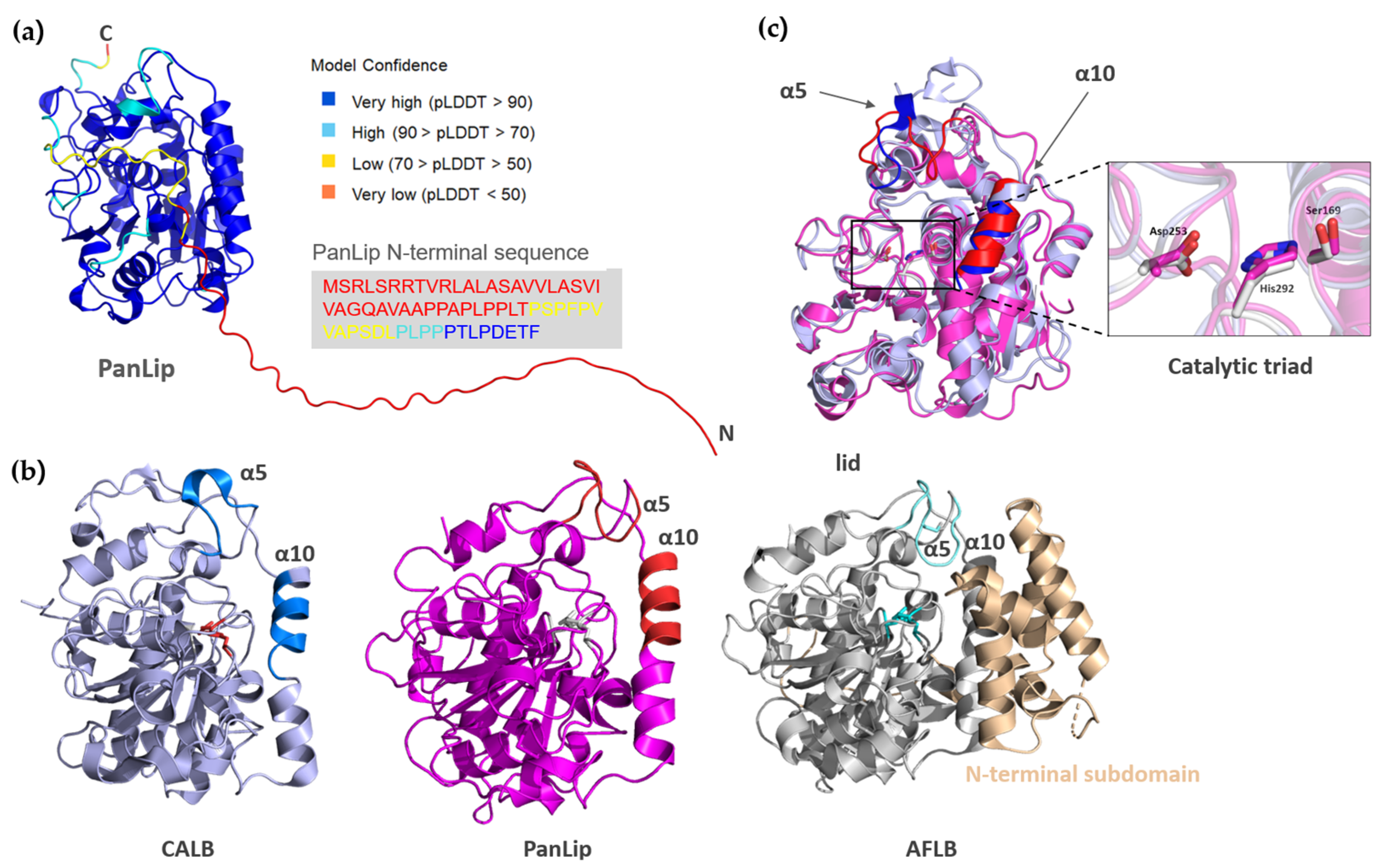

2.1. Primary Structure Analysis and Classification of PanLip

2.2. Cloning, Expression, and Purification of PanLip Proteins

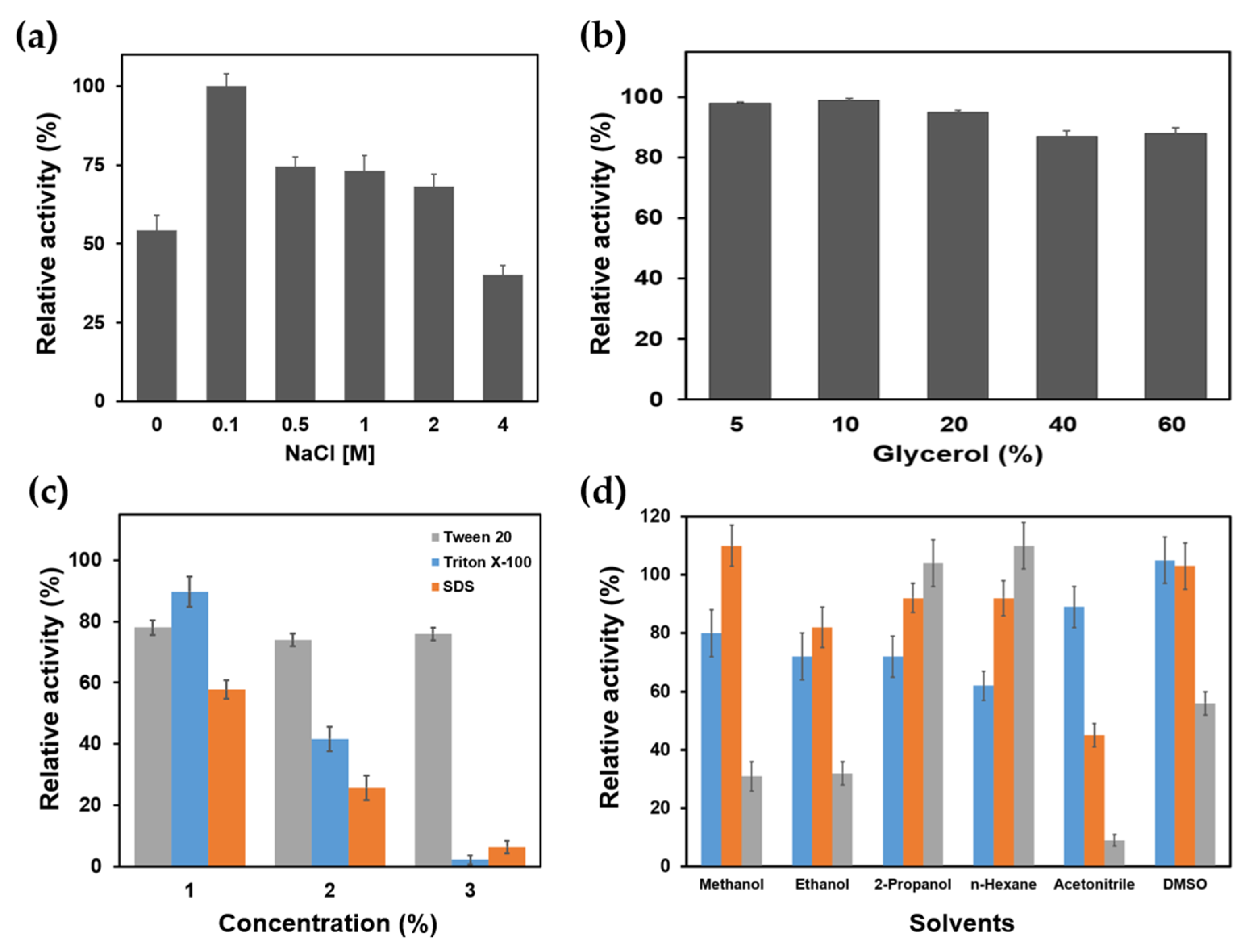

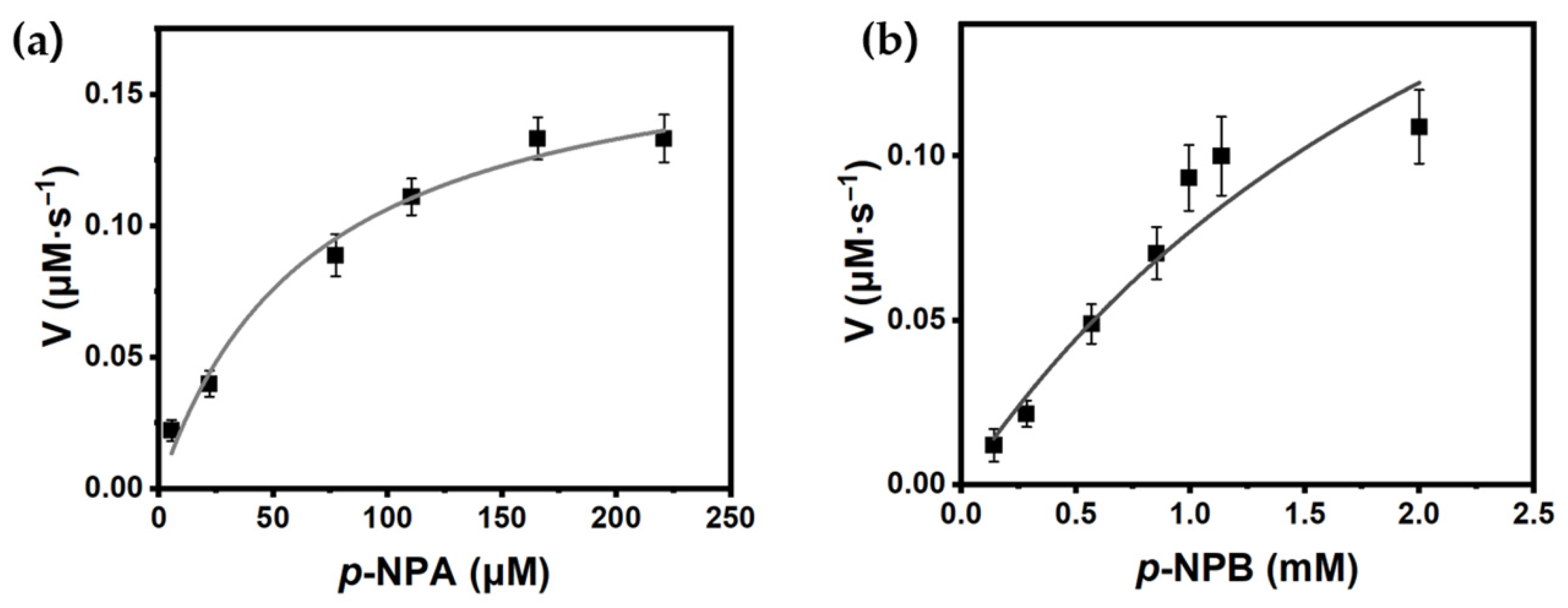

2.3. Biochemical Characterization of PanLipΔN

2.4. Structural Analysis of Alphafold Generated PanLip Model

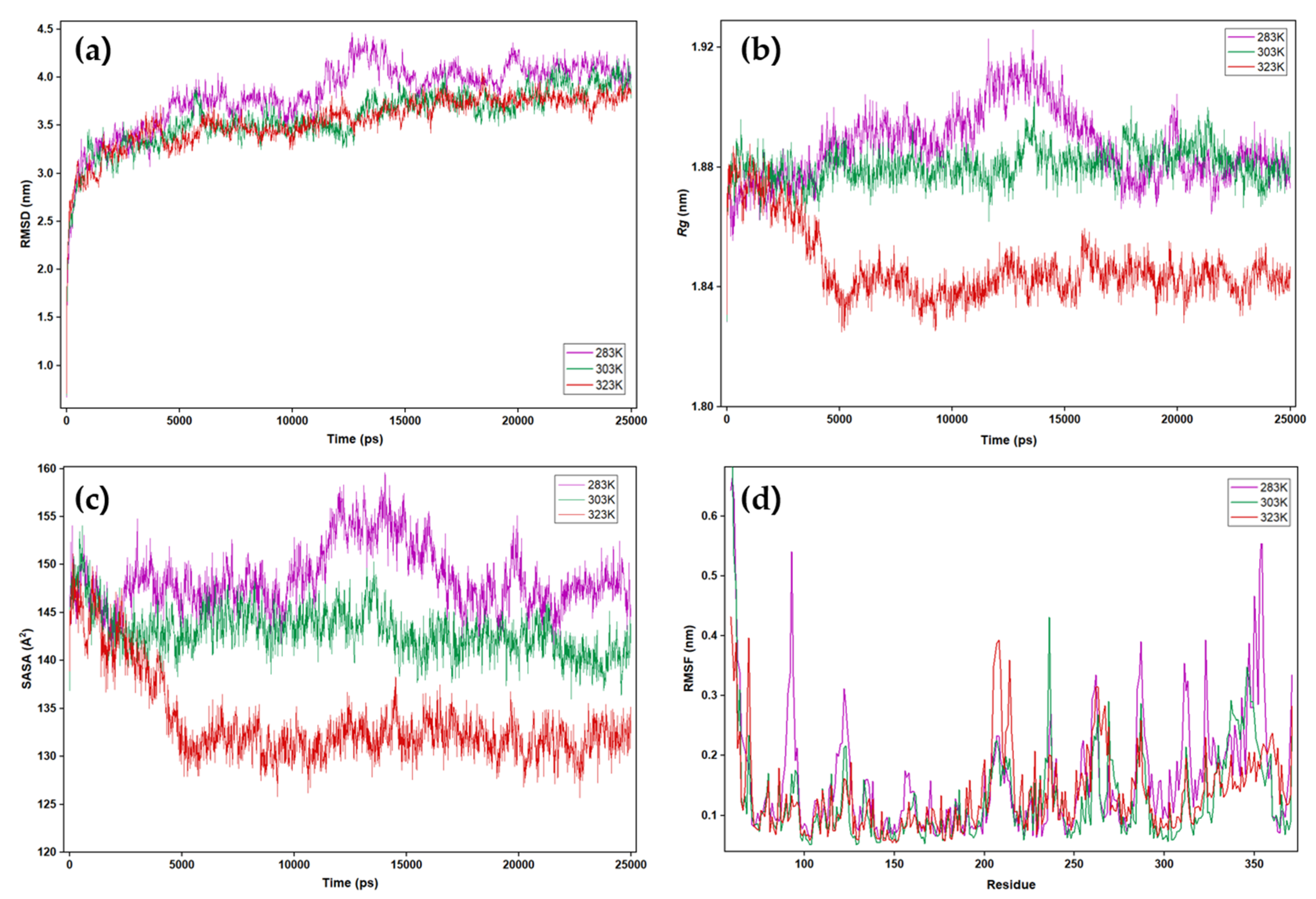

2.5. Analysis of MD Simulation of PanLip Model

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Pseudonocardia Antarctica Lipase

3.3. Enzyme Activity Assay of Recombinant PanLipΔN

3.3.1. Substrate Specificity

3.3.2. Effect of pH and Temperature

3.3.3. Freeze–Thaw Stability

3.3.4. Effects of Additives

3.3.5. Effects of Surfactants and Organic Solvents

3.3.6. Spectroscopy of PanLipΔN

3.3.7. Kinetic Parameter Determination

3.4. Bioinformatic and Structural Model Analysis and MD Simulation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Javed, S.; Azeem, F.; Hussain, S.; Rasul, I.; Siddique, M.H.; Riaz, M.; Afzal, M.; Kouser, A.; Nadeem, H. Bacterial lipases: A review on purification and characterization. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2018, 132, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Godoy, L.; Duquesne, S.; Bordes, F.; Sandoval, G.; Marty, A. Lipases: An overview. Lipases Phospholipases Methods Protoc. 2012, 861, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Abdella, A.; Fakhari, M.; Dong, J.; Yang, K.K.; Yang, S.T. Recent advances in engineering microbial lipases for industrial applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 83, 108658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Li, J.X.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, M.Y.; Qi, C.C.; Wang, C.T. Biological modification and industrial applications of microbial lipases: A general review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 140486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Ahlawat, Y.K.; Stalin, N.; Mehmood, S.; Morya, S.; Malik, A.; Malathi, H.; Nellore, J.; Bhanot, D. Microbial Enzymes in Industrial Biotechnology: Sources, Production, and Significant Applications of Lipases. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 52, kuaf010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alquati, C.; De Gioia, L.; Santarossa, G.; Alberghina, L.; Fantucci, P.; Lotti, M. The cold-active lipase of Pseudomonas fragi. Heterologous expression, biochemical characterization and molecular modeling. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 3321–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, B.; Ramteke, P.W.; Thomas, G. Cold active microbial lipases: Some hot issues and recent developments. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008, 26, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matinja, A.I.; Kamarudin, N.H.A.; Leow, A.T.C.; Oslan, S.N.; Ali, M.S.M. Cold-active lipases and esterases: A review on recombinant overexpression and other essential issues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhetras, N.; Mapare, V.; Gokhale, D. Cold active lipases: Biocatalytic tools for greener technology. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2021, 193, 2245–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkowska, A.; Turkiewicz, M. Miscellaneous Cold-Active Yeast Enzymes of Industrial Importance. In Cold-Adapted Yeasts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Birgisson, H.; Delgado, O.; Garcia Arroyo, L.; Hatti-Kaul, R.; Mattiasson, B. Cold-adapted yeasts as producers of cold-active polygalacturonases. Extremophiles 2003, 7, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzini, P.; Branda, E.; Goretti, M.; Turchetti, B. Psychrophilic yeasts from worldwide glacial habitats: Diversity, adaptation strategies and biotechnological potential. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2012, 82, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Park, H.J.; Kim, I.C.; Yim, J.H. A new approach for discovering cold-active enzymes in a cell mixture of pure-cultured bacteria. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R. Cold-active enzymes as new tools in biotechnology. In Extremophiles, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS); EOLSS Publications: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, K.S.; Cavicchioli, R. Cold-adapted enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006, 75, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olufsen, M.; Smalas, A.O.; Moe, E.; Brandsdal, B.O. Increased flexibility as a strategy for cold adaptation: A comparative molecular dynamics study of cold- and warm-active uracil DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18042–18048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ent, F.; Lund, B.A.; Svalberg, L.; Purg, M.; Chukwu, G.; Widersten, M.; Isaksen, G.V.; Brandsdal, B.O.; Åqvist, J. Structure and mechanism of a cold-adapted bacterial lipase. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Zheng, R.; Cai, R.; Sun, C.; Wu, S. Characterization of two unique cold-active lipases derived from a novel deep-sea cold seep bacterium. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.P.; Heath, C.; Taylor, M.P.; Tuffin, M.; Cowan, D. A novel, extremely alkaliphilic and cold-active esterase from Antarctic desert soil. Extremophiles 2012, 16, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.H.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, H.S.; Kang, S.G.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.H. Cloning and characterization of a new cold-active lipase from a deep-sea sediment metagenome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 81, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.; Yoo, W.; Lee, C.; Wang, Y.; Jeon, S.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.D. Molecular Characterization of a Novel Cold-Active Hormone-Sensitive Lipase (HaHSL) from Halocynthiibacter arcticus. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Giudice, A.; Michaud, L.; de Pascale, D.; De Domenico, M.; di Prisco, G.; Fani, R.; Bruni, V. Lipolytic activity of Antarctic cold-adapted marine bacteria (Terra Nova Bay, Ross Sea). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Te’o, J.; Nevalainen, H. A gene encoding a new cold-active lipase from an Antarctic isolate of Penicillium expansum. Curr. Genet. 2013, 59, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, L.P.; Reyes, F.; Acevedo, J.P.; Salazar, O.; Andrews, B.A.; Asenjo, J.A. Cloning and fusion expression of a cold-active lipase from marine Antarctic origin. Enzyme. Microb. Technol. 2008, 42, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yan, P. Purification and biochemical characterization of a cold-active lipase from Antarctic sea ice bacteria Pseudoalteromonas sp. NJ 70. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 9233–9238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hou, Y.; Lin, X.; Shen, J.; Guan, X. Optimization of cold-active lipase production from psychrophilic bacterium Moritella sp. 2-5-10-1 by statistical experimental methods. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2013, 77, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, G.; Shareck, F.; Hurtubise, Y.; Lepine, F.; Doucet, N. Isolation and characterization of EstC, a new cold-active esterase from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuddus, M.; Ramteke, P.W. Purification and properties of cold-active metalloprotease from Curtobacterium luteum and effect of culture conditions on production. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2008, 24, 2074–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.W.; Zeng, R.Y. Purification and characterization of a cold-adapted alpha-amylase produced by Nocardiopsis sp. 7326 isolated from Prydz Bay, Antarctic. Mar. Biotechnol. 2008, 10, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabahar, V.; Dube, S.; Reddy, G.; Shivaji, S. Pseudonocardia antarctica sp. nov. an actinomycetes from McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 27, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lan, D.; Popowicz, G.M.; Zak, K.M.; Zhao, Z.; Yuan, H.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y. Structure and characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus lipase B with a unique, oversized regulatory subdomain. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 2366–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; An, J.; Yang, G.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, L.; Feng, Y. Enhanced enzyme kinetic stability by increasing rigidity within the active site. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 7994–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boel, E.; Huge-Jensen, B.; Christensen, M.; Thim, L.; Fiil, N.P. Rhizomucor miehei triglyceride lipase is synthesized as a precursor. Lipids 1988, 23, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, H.-D.; Wohlfahrt, G.; Schmid, R.D.; Mccarthy, J.E. The folding and activity of the extracellular lipase of Rhizopus oryzae are modulated by a prosequence. Biochem. J. 1996, 319, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Yu, X.-W. Propeptide in Rhizopus chinensis lipase: New insights into its mechanism of activity and substrate selectivity by computational design. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 4263–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demleitner, G.; Götz, F. Evidence for importance of the Staphylococcus hyicus lipase pro-peptide in lipase secretion, stability and activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1994, 121, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.-C.; Kim, H.-K.; Lee, J.-K.; Kang, S.-C.; Oh, T.-K. Staphylococcus haemolyticus lipase: Biochemical properties, substrate specificity and gene cloning. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999, 179, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Huang, S.; Wang, Z.; Fu, J.; Lv, P.; Miao, C.; Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Luo, W. Enhanced activity of Rhizomucor miehei lipase by directed saturation mutation of the propeptide. Enzyme. Microb. Technol. 2021, 150, 109870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, O.V.; Blagova, E.; Reiser, V.; Saikia, R.; Dalal, S.; Jørgensen, C.I.; Bhatia, V.K.; Baunsgaard, L.; Andersen, B.; Svendsen, A. Novel inhibitory function of the Rhizomucor miehei lipase propeptide and three-dimensional structures of its complexes with the enzyme. Acs Omega 2019, 4, 9964–9975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, S.; Marx, J.-C.; Gerday, C.; Feller, G. Activity-stability relationships in extremophilic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 7891–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjelic, S.; Brandsdal, B.O.; Aqvist, J. Cold adaptation of enzyme reaction rates. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 10049–10057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matinja, A.I.; Kamarudin, N.H.A.; Leow, A.T.C.; Oslan, S.N.; Ali, M.S.M. Structural Insights into Cold-Active Lipase from Glaciozyma antarctica PI12: Alphafold2 Prediction and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Mol. Evol. 2024, 92, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Choi, J.M.; Kim, H.J. Crystal structure of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from a psychrophilic bacterium, Colwellia psychrerythraea 34H. Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 492, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksen, G.V.; Åqvist, J.; Brandsdal, B.O. Enzyme surface rigidity tunes the temperature dependence of catalytic rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7822–7827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Ent, F.; Yu, S.; Lund, B.A.; Brandsdal, B.O.; Sheng, X.; Åqvist, J. Computational Design of Highly Efficient Cold-Adapted Enzymes with Elevated Temperature Optima. ACS Catal. 2025, 15, 11257–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitch, T.C.; Clavel, T. A proposed update for the classification and description of bacterial lipolytic enzymes. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, F.; Babic, N.; Krauss, U.; Jaeger, K.-E. Classification of Lipolytic Enzymes from Bacteria. In Aerobic Utilization of Hydrocarbons, Oils and Lipids; Spring Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nisole, A.; Lussier, F.-X.; Morley, K.L.; Shareck, F.; Kazlauskas, R.J.; Dupont, C.; Pelletier, J.N. Extracellular production of Streptomyces lividans acetyl xylan esterase A in Escherichia coli for rapid detection of activity. Protein Expr. Purif. 2006, 46, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, C. High secretory production of an alkaliphilic actinomycete xylanase and functional roles of some important residues. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 2053–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Pang, X.; Lv, J. Development an effective system to expression recombinant protein in E. coli via comparison and optimization of signal peptides: Expression of Pseudomonas fluorescens BJ-10 thermostable lipase as case study. Microb. Cell Fact. 2018, 17, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, I.Y.; Prieto, E.; Pieffet, G.P.; Méndez, L.; Jiménez-Junca, C.A. Functional heterologous expression of mature lipase LipA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PSA01 in Escherichia coli SHuffle and BL21 (DE3): Effect of the expression host on thermal stability and solvent tolerance of the enzyme produced. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, M.N.; Sabri, S.; mohd Yahaya, N.; Sharif, F.M.; Ali, M.S.M. Catalytically Active Inclusion Bodies of Cold-Adapted Lipase: Production and Its Industrial Potential. AMB Expr. 2025, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novototskaya-Vlasova, K.; Petrovskaya, L.; Kryukova, E.; Rivkina, E.; Dolgikh, D.; Kirpichnikov, M. Expression and chaperone-assisted refolding of a new cold-active lipase from Psychrobacter cryohalolentis K5(T). Protein Expr. Purif. 2013, 91, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Wi, A.R.; Park, H.J.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.W.; Yim, J.H.; Han, S.J. Enhancing Extracellular Lipolytic Enzyme Production in an Arctic Bacterium, Psychrobacter sp. ArcL13, by Using Statistical Optimization and Fed-Batch Fermentaion. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 45, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, S. High-level expression and biochemical characterization of a novel cold-active lipase from Rhizomucor endophyticus. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joerger, R.D.; Haas, M.J. Overexpression of aRhizopus delemar lipase gene in Escherichia coli. Lipids 1993, 28, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Hidalgo, A.; Haas, M.; Bornscheuer, U.T. Heterologous production of functional forms of Rhizopus oryzae lipase in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 8974–8977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsonai, A.; Bulyáki, É.; Kardos, J. BeStSel: From Secondary Structure Analysis to Protein Fold Prediction by Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy. In Structural Genomics: General Applications; Chen, Y.W., Yiu, C.-P.B., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Esakkiraj, P.; Bharathi, C.; Ayyanna, R.; Jha, N.; Panigrahi, A.; Karthe, P.; Arul, V. Functional and molecular characterization of a cold-active lipase from Psychrobacter celer PU3 with potential antibiofilm property. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 211, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, S. Heterologous expression and biochemical characterization of a cold-active lipase from Rhizopus microsporus suitable for oleate synthesis and bread making. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Margesin, R. Partial characterization of a crude cold-active lipase from Rhodococcus cercidiphylli BZ22. Folia Microbiol. 2014, 59, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Ali, M.S.; Mohd Fuzi, S.F.; Ganasen, M.; Abdul Rahman, R.N.; Basri, M.; Salleh, A.B. Structural adaptation of cold-active RTX lipase from Pseudomonas sp. strain AMS8 revealed via homology and molecular dynamics simulation approaches. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 925373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-H.; Yoo, W.; Lee, C.W.; Jeong, C.S.; Shin, S.C.; Kim, H.-W.; Park, H.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, T.D.; Lee, J.H. Crystal structure and functional characterization of a cold-active acetyl xylan esterase (Pb AcE) from psychrophilic soil microbe Paenibacillus sp. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.T.H.L.; Yoo, W.; Jeon, S.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, T.D. Biodiesel and flavor compound production using a novel promiscuous cold-adapted SGNH-type lipase (Ha SGNH1) from the Psychrophilic bacterium Halocynthiibacter arcticus. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salwoom, L.; Raja Abd Rahman, R.N.Z.; Salleh, A.B.; Mohd Shariff, F.; Convey, P.; Mohamad Ali, M.S. New recombinant cold-adapted and organic solvent tolerant lipase from Psychrophilic Pseudomonas sp. LSK25, isolated from Signy Island Antarctica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti-Lafranconi, P.; Natalello, A.; Rehm, S.; Doglia, S.M.; Pleiss, J.; Lotti, M. Evolution of stability in a cold-active enzyme elicits specificity relaxation and highlights substrate-related effects on temperature adaptation. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 395, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, D.M.; Yang, N.; Wang, W.K.; Shen, Y.F.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.H. A novel cold-active lipase from Candida albicans: Cloning, expression and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 3950–3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C. Purification and characterization of halophilic lipase of Chromohalobacter sp. from ancient salt well. J. Basic Microbiol. 2018, 58, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, H.; Hafiz Kasim, F.; Nagoor Gunny, A.A.; Gopinath, S.C.; Azmier Ahmad, M. Enhanced halophilic lipase secretion by Marinobacter litoralis SW-45 and its potential fatty acid esters release. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Lan, D.; Xin, R.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y. Biochemical properties of a new cold-active mono- and diacylglycerol lipase from marine member Janibacter sp. strain HTCC2649. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 10554–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Hemar, Y.; Li, N.; Zhou, P. Glycerol induced stability enhancement and conformational changes of β-lactoglobulin. Food Chem. 2020, 308, 125596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, V.; Daschakraborty, S. Influence of glycerol on the cooling effect of pair hydrophobicity in water: Relevance to proteins’ stabilization at low temperature. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, P.; Rabbani, G.; Badr, G.; Badr, B.M.; Khan, R.H. The surfactant-induced conformational and activity alterations in Rhizopus niveus lipase. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 71, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, D. Lipase catalysis in presence of nonionic surfactants. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2020, 191, 744–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Nie, K.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, F.; Kuang, Y.; Yan, H.; Fang, Y.; Yang, H.; Nishinari, K.; Phillips, G.O. The influence of non-ionic surfactant on lipid digestion of gum Arabic stabilized oil-in-water emulsion. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachurska, K.; Marcisz, U.; Długosz, M.; Antosiewicz, J.M. Kinetics of Structural Transitions Induced by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate in α-Chymotrypsin. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 49137–49149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Saha, D.; Ray, D.; Aswal, V.K. Surfactant-driven modifications in protein structure. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 4979–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoramnia, A.; Ebrahimpour, A.; Beh, B.K.; Lai, O.M. Production of a Solvent, Detergent, and Thermotolerant Lipase by a Newly Isolated Acinetobacter sp. in Submerged and Solid-State Fermentations. BioMed Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 702179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko Sukohidayat, N.H.; Zarei, M.; Baharin, B.S.; Manap, M.Y. Purification and characterization of lipase produced by Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides ATCC 8293 using an aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) composed of triton X-100 and maltitol. Molecules 2018, 23, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanavas, P.; Khuchareontaworn, S.; Khawsak, P.; Pakpitcharoen, A.; Pothivejkul, K.; Santiwatanakul, S.; Matsui, K.; Kajiwara, T.; Chansiri, K. Purification and characterization of organic solvent and detergent tolerant lipase from thermotolerant Bacillus sp. RN2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 3783–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbosch, K.N.; Vieyto-Nuñez, J.C.; Ruiz-Blanco, Y.B.; Mayer, C.; Hoffmann-Jacobsen, K.; Sanchez-Garcia, E. Effect of organic solvents on the structure and activity of a minimal lipase. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 87, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Jaimes, I.; Mora-Lugo, R.; Calcagno, M.L.; Farrés, A. Kinetic studies of Gly28: Ser mutant form of Bacillus pumilus lipase: Changes in kcat and thermal dependence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 2222–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.; Magana, P.; Nair, S.; Tsenkov, M.; Bertoni, D.; Pidruchna, I.; Afonso, M.Q.L.; Midlik, A.; Paramval, U.; Zidek, A.; et al. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database and 3D-Beacons: New Data and Capabilities. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.J.; Headd, J.J.; Moriarty, N.W.; Prisant, M.G.; Videau, L.L.; Deis, L.N.; Verma, V.; Keedy, D.A.; Hintze, B.J.; Chen, V.B.; et al. MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, L. Dali server: Structural unification of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W210–W215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.M.J.; Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; Xue, B.; Yew, W.S.; Nguyen, G.K.T. A Novel Lipase from Lasiodiplodia theobromae Efficiently Hydrolyses C8–C10 Methyl Esters for the Preparation of Medium-Chain Triglycerides’ Precursors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hou, S.; Lan, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Khan, F.I.; Wang, Y. Crystal structure of a lipase from Streptomyces sp. strain W007–implications for thermostability and regiospecificity. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 3506–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.G.; Che, X.Y.; Li, L.L.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.H. Engineered lipase from Janibacter sp. with high thermal stability to efficiently produce long-medium-long triacylglycerols. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 165, 113675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.M.; Godoy, A.S.; Kadowaki, M.A.S.; Trentin, L.N.; Gonzalez, S.E.; Skaf, M.S.; Polikarpov, I. Structures of Bl Est2 from Bacillus licheniformis in its propeptide and mature forms reveal autoinhibitory effects of the C-terminal domain. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 4930–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, G.; Gupta, P.; Nonato, M.C.; Tandel, S.; Biehl, E.R.; Hofmann, S.L.; Clardy, J. The crystal structure of palmitoyl protein thioesterase-2 (PPT2) reveals the basis for divergent substrate specificities of the two lysosomal thioesterases, PPT1 and PPT2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37957–37964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Kondo, H.; Suzuki, M.; Ohgiyai, S.; Tsuda, S. Alternate conformations observed in catalytic serine of Bacillus subtilis lipase determined at 1.3 Å resolution. Biol. Crystallogr. 2002, 58, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jendrossek, D.; Hermawan, S.; Subedi, B.; Papageorgiou, A.C. Biochemical analysis and structure determination of P. aucimonas lemoignei poly (3-hydroxybutyrate)(PHB) depolymerase PhaZ 7 muteins reveal the PHB binding site and details of substrate–enzyme interactions. Mol. Microbiol. 2013, 90, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, G.H.; Kiehstaller, S.; Poc, P.; Lewis, A.H.; Oh, J.; Sadighi, R.; Pearce, N.M.; Ibrahim, M.; Drienovská, I.; Rijs, A.M. Covalent bicyclization of protein complexes yields durable quaternary structures. Chem 2024, 10, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, J. Enhancing the Thermostability of a Cold-Active Lipase from Penicillium cyclopium by In Silico Design of a Disulfide Bridge. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 1752–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Taghdir, M.; Joozdani, F.A. Dynamozones are the most obvious sign of the evolution of conformational dynamics in HIV-1 protease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, M.; Bogatyreva, N.S.; Galzitskaia, O.V. Radius of gyration is indicator of compactness of protein structure. Mol. Biol. 2008, 42, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, G.V.; Åqvist, J.; Brandsdal, B.O. Protein surface softness is the origin of enzyme cold-adaptation of trypsin. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacob, N.; Kamonsutthipaijit, N.; Soontaranon, S.; Leow, T.C.; Abd Rahman, R.N.Z.R.; Ali, M.S.M. Structural interpretations of a flexible cold-active AMS8 lipase by combining small-angle X-ray scattering and molecular dynamics simulation (SAXS-MD). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, M.N.; Rahman, R.N.Z.R.A.; Noor, N.D.M.; Latip, W.; Knight, V.F.; Ali, M.S.M. Exploring the Antarctic aminopeptidase P from Pseudomonas sp. strain AMS3 through structural analysis and molecular dynamics simulation. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2025, 43, 6239–6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisis, T.; Freddolino, L.; Turunen, P.; van Teeseling, M.C.F.; Rowan, A.E.; Blank, K.G. Interfacial Activation of Candida antarctica Lipase B: Combined Evidence from Experiment and Simulation. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5969–5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamroz, M.; Kolinski, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex: Server for fast simulation of protein structure fluctuations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W427–W431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kielkopf, C.L.; Bauer, W.; Urbatsch, I.L. Bradford assay for determining protein concentration. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2020, 2020, pdb.prot102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umetsu, M.; Tsumoto, K.; Hara, M.; Ashish, K.; Goda, S.; Adschiri, T.; Kumagai, I. How additives influence the refolding of immunoglobulin-folded proteins in a stepwise dialysis system: Spectroscopic evidence for highly efficient refolding of a single-chain Fv fragment. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 8979–8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.e.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, H. Practical Applications of Language Models in Protein Sorting Prediction: SignalP 6.0, DeepLoc 2.1, and DeepLocPro 1.0. In Large Language Models (LLMs) in Protein Bioinformatics; Kc, D.B., Ed.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, G.A.; Friesner, R.A.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Evaluation and reparametrization of the OPLS-AA force field for proteins via comparison with accurate quantum chemical calculations on peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 6474–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PDB ID | Z-Score | rmsd | Identity (%) | aln/nres 1 | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6IDY | 56.0 | 0.6 | 31 | 311/421 | Aspergillus fumigatus | [31] |

| 7V6D | 47.7 | 1.4 | 28 | 307/366 | Lasiodiplodia theobromae | [86] |

| 4K6G | 40.3 | 1.8 | 30 | 289/319 | Candida antarctica | [32] |

| 5H6B | 24.8 | 2.2 | 27 | 220/252 | Streptomyces sp. W007 | [87] |

| 7V3K | 24.0 | 2.4 | 25 | 224/294 | Janibacter sp. HTCC2649 | [88] |

| 6WPY | 19.3 | 2.7 | 17 | 201/245 | Bacillus licheniformis | [89] |

| 1PJA | 17.9 | 2.5 | 15 | 193/268 | Homo sapiens | [90] |

| 1ISP | 17.6 | 1.8 | 23 | 163/179 | Bacillus subtilis | [91] |

| 4BRS | 17.5 | 3.2 | 13 | 220/332 | Paucimonas lemoignei | [92] |

| 8PI1 | 17.3 | 2.8 | 13 | 199/271 | Pseudomonas fluorescens | [93] |

| Plasmids/Primers | Description |

|---|---|

| Plasmids | |

| pET-22a-PanLip | Amp r; codon-optimized P. antarctica lipase gene inserted into NcoI/HindIII |

| pET-28a-PanLip | Kan r; codon-optimized P. antarctica lipase gene inserted into NdeI/BamHI |

| pET-32a-PanLip | Amp r; codon-optimized P. antarctica lipase gene inserted into NcoI/HindIII |

| pET-28a-PanLipΔN | Kan r; N-terminal deleted codon-optimized P. antarctica lipase gene inserted into NdeI/XhoI |

| Primers | |

| ΔN-F | 5′–GCGGCATATGACTCTGCCGGATGAGAC–3′ (underlined was NdeI) |

| ΔN-R | 5′–GCGGCTCGAGTTATTCCAGTAGGTTCTGTTTC–3′ (underlined was XhoI) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Do, H.; Kim, J.-O.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.J. A CALB-like Cold-Active Lipolytic Enzyme from Pseudonocardia antarctica: Expression, Biochemical Characterization, and AlphaFold-Guided Dynamics. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120480

Liu L, Do H, Kim J-O, Lee JH, Kim HJ. A CALB-like Cold-Active Lipolytic Enzyme from Pseudonocardia antarctica: Expression, Biochemical Characterization, and AlphaFold-Guided Dynamics. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120480

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lixiao, Hackwon Do, Jong-Oh Kim, Jun Hyuck Lee, and Hak Jun Kim. 2025. "A CALB-like Cold-Active Lipolytic Enzyme from Pseudonocardia antarctica: Expression, Biochemical Characterization, and AlphaFold-Guided Dynamics" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120480

APA StyleLiu, L., Do, H., Kim, J.-O., Lee, J. H., & Kim, H. J. (2025). A CALB-like Cold-Active Lipolytic Enzyme from Pseudonocardia antarctica: Expression, Biochemical Characterization, and AlphaFold-Guided Dynamics. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120480