Exploiting the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae for the Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and an Investigation of Their Antioxidant Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Au@RO, Ag@RO and Pt@RO and Characterization by UV-Vis

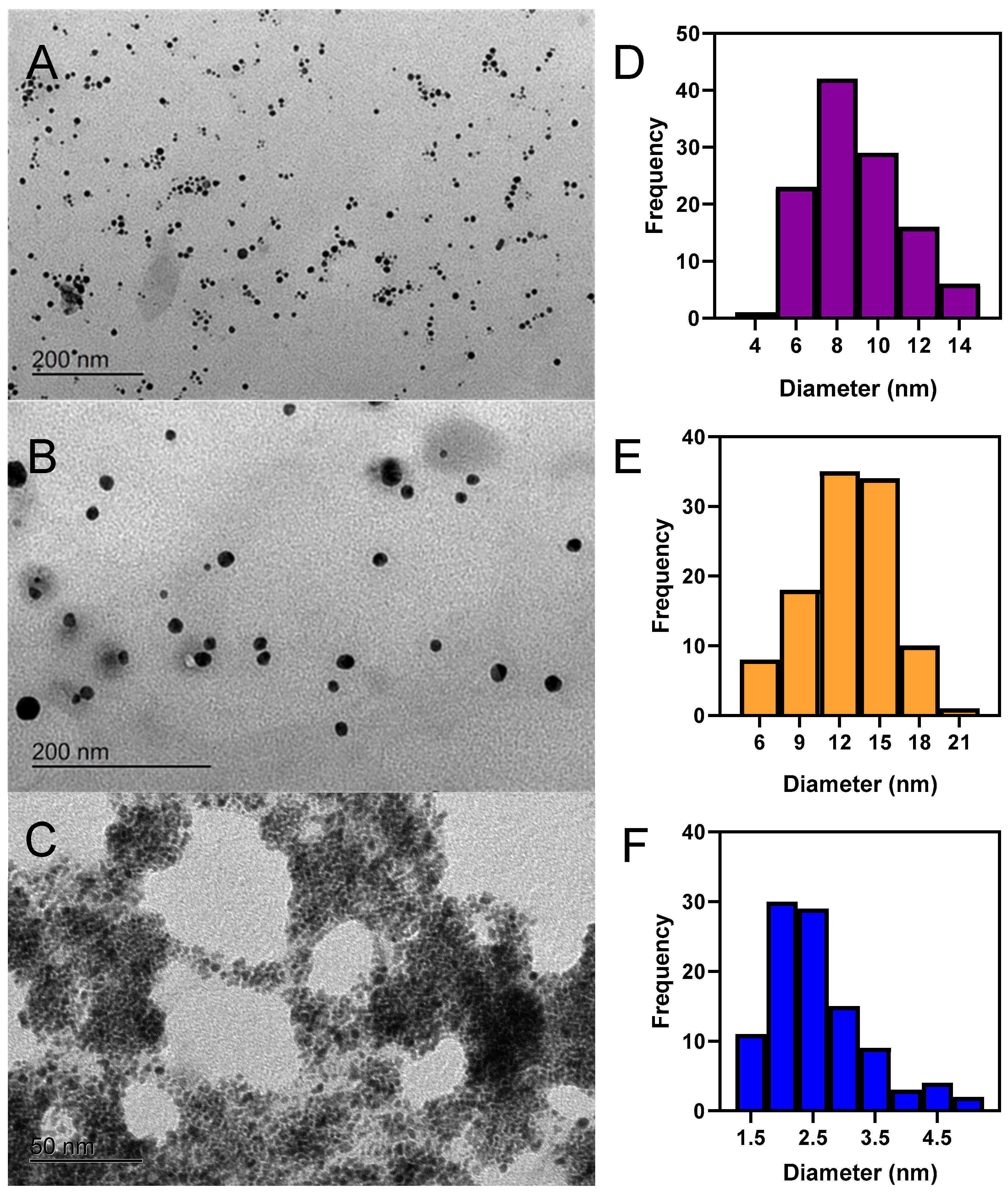

2.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy Characterization of Au@RO, Ag@RO and Pt@RO

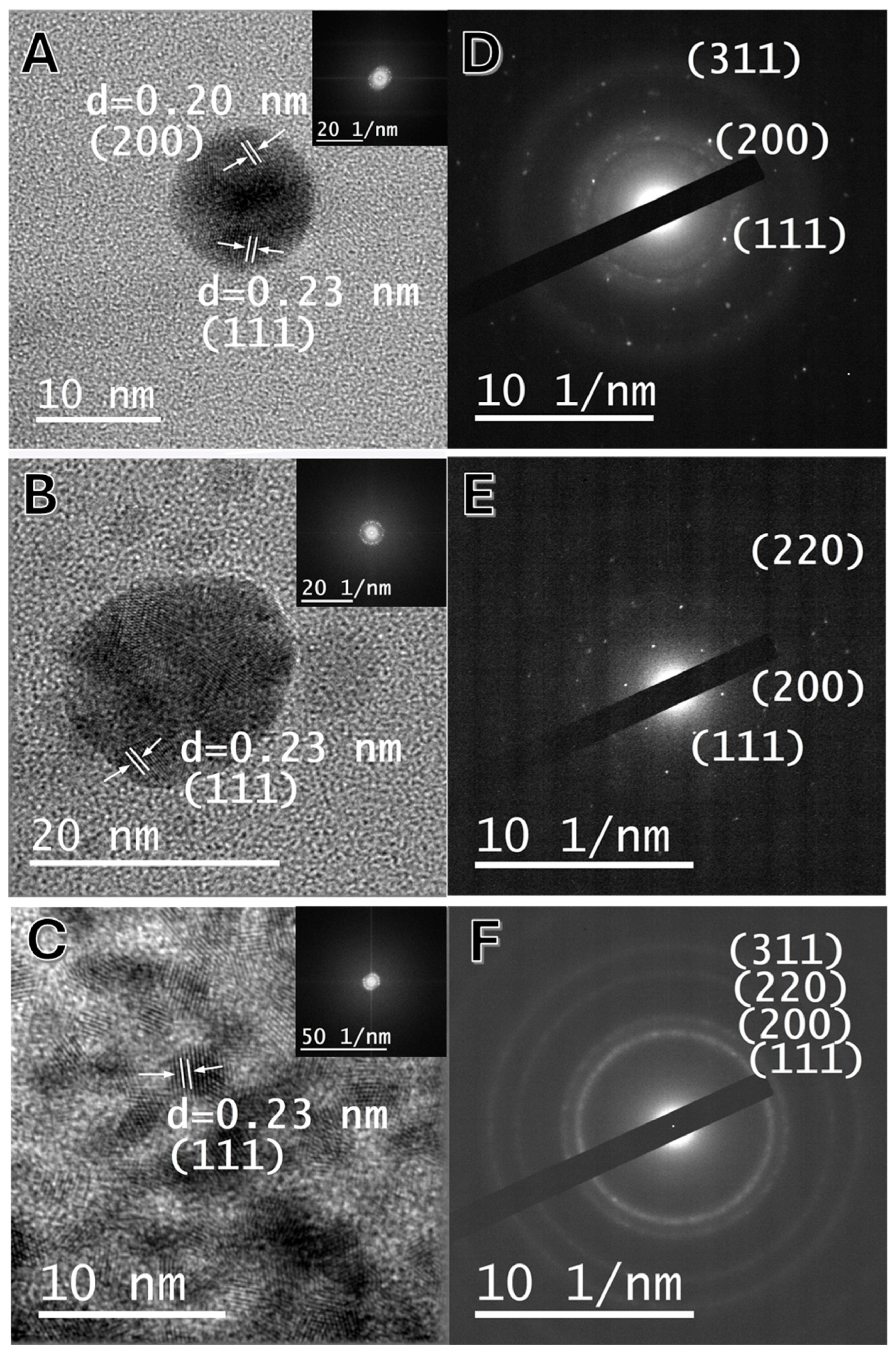

2.3. Crystallinity Characterization of Au@RO, Ag@RO and Pt@RO by XRD and HRTEM

2.4. Surface Charge of Au@RO,Ag@RO and Pt@RO

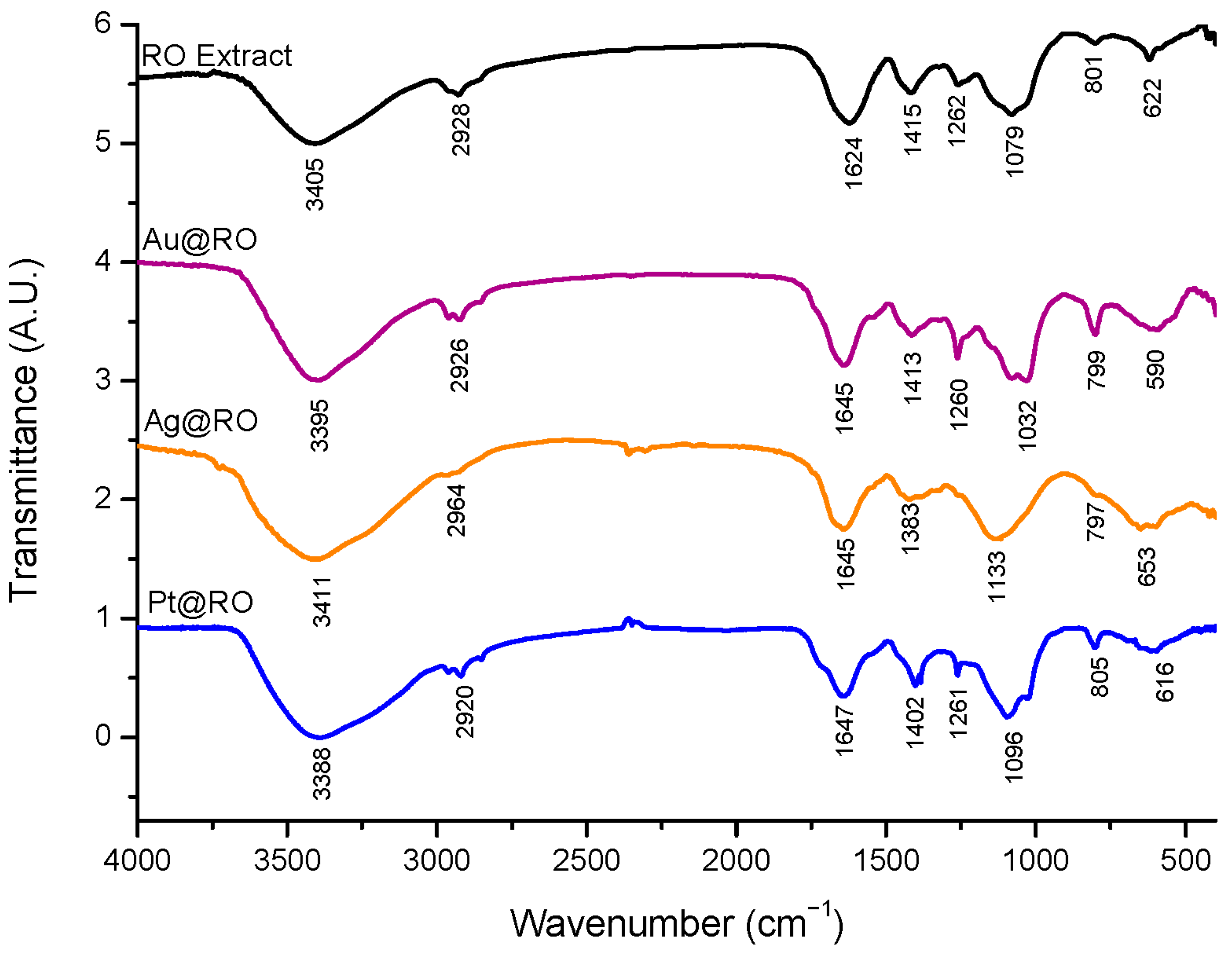

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Characterization

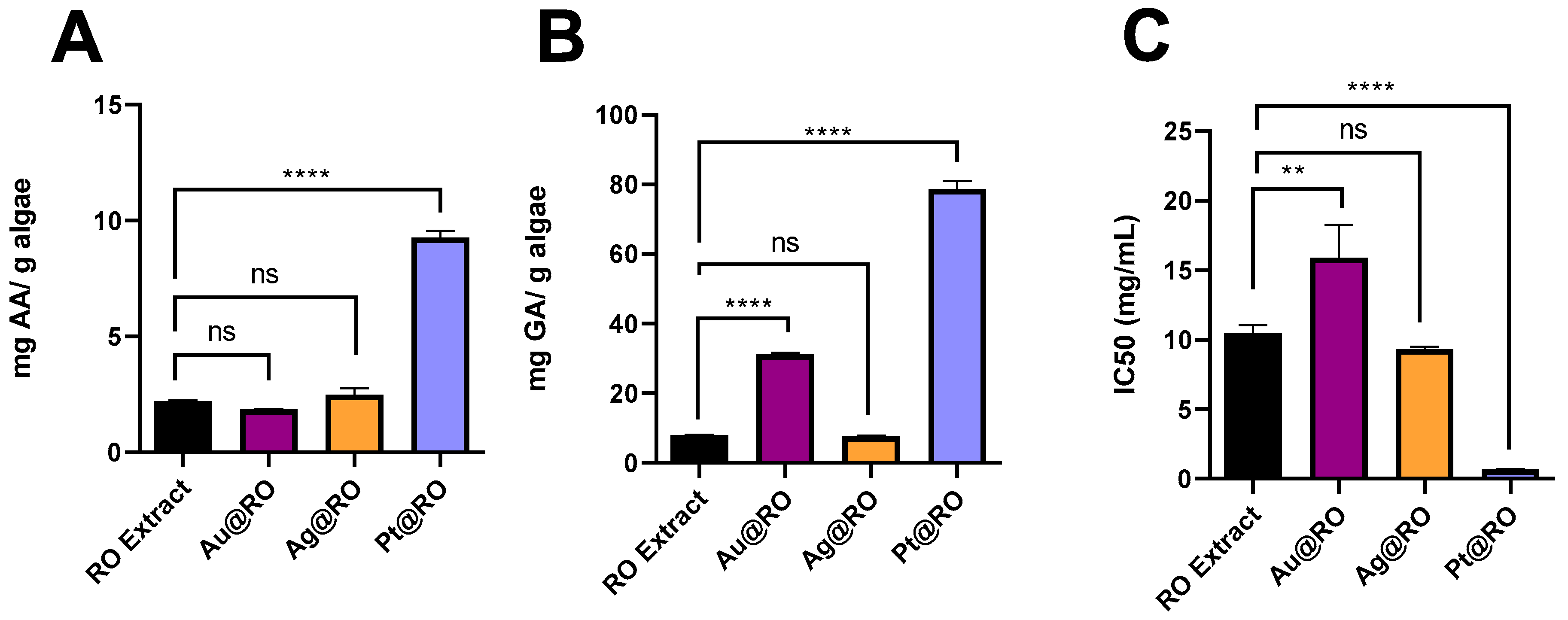

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Algae Collection and Extract Preparation

3.2. Synthesis of Gold, Silver, and Platinum Nanoparticles

3.3. Characterization Techniques

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

3.4.1. Reducing Power

3.4.2. Total Phenolic Content

3.4.3. DPPH Scavenging Activity

3.4.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Román, S.; Vázquez, R. Assessment of the Rugulopteryx okamurae Invasion in Northeastern Atlantic and Mediterranean Bioregions: Colonisation Status, Propagation Hypotheses and Temperature Tolerance Thresholds. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 207, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tapia, P.; Alvite, N.; Bañón, R.; Barreiro, R.; Barrientos, S.; Bustamante, M.; Carrasco, S.; Cremades, J.; Iglesias, S.; López Rodríguez, M.d.C.; et al. Multiple Introduction Events Expand the Range of the Invasive Brown Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae to Northern Spain. Aquat. Bot. 2025, 196, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz-Villegas, S.; De La Hoz, C.F.; Juanes, J.A.; Puente, A. Predicting Non-Native Seaweeds Global Distributions: The Importance of Tuning Individual Algorithms in Ensembles to Obtain Biologically Meaningful Results. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1009808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, L.F.; Pham, C.K.; Menezes, G.; Bettencourt, R.; Rocha, N.; Carvalho, M.; Felgueiras, H.P. A Concise Review on the Potential Applications of Rugulopteryx okamurae Macroalgae. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remya, R.R.; Samrot, A.V.; Kumar, S.S.; Mohanavel, V.; Karthick, A.; Chinnaiyan, V.K.; Umapathy, D.; Muhibbullah, M. Bioactive Potential of Brown Algae. Adsorpt. Sci. Amp Technol. 2022, 2022, 9104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, R.; Chen, S.; Ding, R.; Liu, X.; Luo, L.; Xia, Q.; Zhong, S.; Qi, Y.; et al. Determining the Potent Immunostimulation Potential Arising from the Heteropolysaccharide Structure of a Novel Fucoidan, Derived from Sargassum zhangii. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barciela, P.; Carpena, M.; Li, N.; Liu, C.; Jafari, S.M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Macroalgae as Biofactories of Metal Nanoparticles; Biosynthesis and Food Applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 311, 102829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Virmani, T.; Yadav, S.K.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, G.; Alhalmi, A. Breaking Barriers in Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Plant-Mediated Metal/Metal Oxide/Bimetallic Nanoparticles: Antibacterial, Anticancer, Mechanism Elucidation, and Versatile Utilizations. J. Nanomater. 2024, 2024, 9914079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Gao, F.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Xiong, T.; Yi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Tang, X. Metallic Nanoparticles Synthesized by Algae: Synthetic Route, Action Mechanism, and the Environmental Catalytic Applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 12, 111742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Khan, A.M.; Shujait, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Ikram, M.; Imran, M.; Haider, J.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Synthesis of Nanomaterials using various Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches, Influencing Factors, Advantages, and Disadvantages: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 300, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Fernandes, M.; Machado, R.; Sampaio, P.; Gomes, A.C.; Cavazza, A.; Bigi, F.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C. Valorisation of the Invasive Macroalgae Undaria pinnatifida (Harvey) Suringar for the Green Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles with Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Potential. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Badr, M.M.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; et al. Synthesis of Green Nanoparticles for Energy, Biomedical, Environmental, Agricultural, and Food Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Hernández, J.A.; Velarde-Salcedo, A.; Navarro-Tovar, G.; Gonzalez, C. Safe Nanomaterials: From their use, Application, and Disposal to Regulations. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 1583–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afolabi, R.O. A Comprehensive Review of Nanosystems’ Multifaceted Applications in Catalysis, Energy, and the Environment. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 397, 124190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaison, J.P.; Balasubramanian, B.; Gangwar, J.; Pappuswamy, M.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Kamyab, H.; Paari, K.A.; Liu, W.; Taheri, M.M.; Joseph, K.S. Bioactive Nanoparticles Derived from Marine Brown Seaweeds and their Biological Applications: A Review. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehra, S.H.; Ramzan, K.; Viskelis, J.; Viskelis, P.; Balciunaitiene, A. Advancements in Green Synthesis of Silver-Based Nanoparticles: Antimicrobial and Antifungal Properties in various Films. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Z.; Saleem, R.; Khan, R.R.M.; Liaqat, M.; Pervaiz, M.; Saeed, Z.; Muhammad, G.; Amin, M.; Rasheed, S. Green Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Potential of Gold Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 59, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Hazra, R.; Kar, A.; Ghosh, P.; Patra, P. Platinum Nanoparticles: Tiny Titans in Therapy. Discov. Mater. 2024, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, N.H.; Mohamad Nor, N.; Abu Bakar, A.H.; Zakaria, N.D.; Lockman, Z.; Abdul Razak, K. Platinum-Based Nanoparticles: A Review of Synthesis Methods, Surface Functionalization, and their Applications. Microchem. J. 2024, 200, 110280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Size and Temperature Dependence of the Plasmon Absorption of Colloidal Gold Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4212–4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Maietta, I.; Rey-Méndez, R.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Lastra-Valdor, M.; Cavazza, A.; Grimaldi, M.; Bigi, F.; Simón-Vázquez, R. Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized by an Aqueous Extract of Codium tomentosum as Potential Antitumoral Enhancers of Gemcitabine. Mar. Drugs 2022, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Diego-González, L.; Lastra-Valdor, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Bigi, F.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Simón-Vázquez, R. Saccorhiza polyschides used to Synthesize Gold and Silver Nanoparticles with Enhanced Antiproliferative and Immunostimulant Activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 123, 111960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Lastra-Valdor, M.; González-Mediero, G.; Rey-Cao, S.; Grimaldi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Bigi, F. Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles by Sargassum muticum Biomolecules and Evaluation of their Antioxidant Activity and Antibacterial Properties. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2020, 10, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, F.; Azizi, S.; Ahmad, M.B.; Shameli, K.; Mohamad, R.; Mahdavi, M.; Tahir, P.M. Green Synthesis and Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles using the Marine Macroalgae Sargassum muticum. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 5723–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, M.; Suresh, M.; Palaniyandi, T.; Viswanathan, S.; Wahab, M.R.A.; Baskar, G.; Surendran, H.; Ravi, M.; Sivaji, A. Bio-Fabrication of Gold Nanoparticles from Brown Seaweeds for Anticancer Activity Against Glioblastoma through Invitro and Molecular Docking Approaches. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1281, 135178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kalaivani, R.; Manikandan, S.; Sangeetha, N.; Kumaraguru, A.K. Facile Green Synthesis of Variable Metallic Gold Nanoparticle using Padina gymnospora, a Brown Marine Macroalga. Appl. Nanosci. 2013, 3, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizki, I.N.; Klaypradit, W.; Patmawati. Utilization of Marine Organisms for the Green Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles and their Applications: A Review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 31, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, H.; Abdelsalam, A.; Morad, M.Y.; Sonbol, H.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Tawfik, E. Phyto-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles from Sargassum subrepandum: Anticancer, Antimicrobial, and Molluscicidal Activities. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1403753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, R.A.; Aljohani, E.S. Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Derived from Brown Algae Sargassum vulgare: Insight into Antioxidants, Anticancer, Antibacterial and Hepatoprotective Effect. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaraman, P.; Balasubramanian, B.; Kaliannan, D.; Durai, M.; Kamyab, H.; Park, S.; Chelliapan, S.; Lee, C.T.; Maluventhen, V.; Maruthupandian, A. Phyco-Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Mediated from Marine Algae Sargassum Myriocystum and its Potential Biological and Environmental Applications. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.M.; Fawzy, E.M.; Shehab, R.A.; Abdel-Salam, M.O.; Salah El Din, R.A.; Abd El Fatah, H.M. Production, Characterization, and Cytotoxicity Effects of Silver Nanoparticles from Brown Alga (Cystoseira myrica). J. Nanotechnol. 2022, 2022, 6469090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Gupta, K.; Chundawat, T.S. In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity of Biogenically Synthesized Palladium and Platinum Nanoparticles using Botryococcus braunii. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 17, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, M.; Arslan, Y.; Tomul, F.; Akgül, F.; Akgül, R. Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles from Codium Macroalgae for Wastewater Pollutants Removal by Adsorption. Clean Soil Air Water 2024, 52, 2300187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, V.S.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Prakash, S.; Ahila, N.K.; Vinoj, G.; Selvam, S.; Kumar, G.; Kannapiran, E.; Rajendran, R.B. Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles using Seaweed Padina gymnospora and their Catalytic Activity as PVP/PtNPs Nanocomposite Towards Biological Applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiny, P.J.; Mukherjee, A.; Chandrasekaran, N. Haemocompatibility Assessment of Synthesised Platinum Nanoparticles and its Implication in Biology. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 37, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyaraj, G.; Vinosha, M.; Sangeetha, D.; Manikandakrishnan, M.; Palanisamy, S.; Sonaimuthu, M.; Manikandan, R.; You, S.; Prabhu, N.M. Bio-Directed Synthesis of Pt-Nanoparticles from Aqueous Extract of Red Algae Halymenia dilatata and their Biomedical Applications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 618, 126434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, C.; Ladisa, M.; Altamura, D.; Siliqi, D.; Sibillano, T.; De Caro, L. X-Ray Diffraction: A Powerful Technique for the Multiple-Length-Scale Structural Analysis of Nanomaterials. Crystals 2016, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorokh, A.S. Scherrer Formula: Estimation of Error in Determining Small Nanoparticle Size. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 2018, 9, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and Zeta Potential—What they are and what they are Not? J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayagam, R.; Nagendran, V.; Goveas, L.C.; Narasimhan, M.K.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Chandrasekar, N.; Selvaraj, R. Structural Characterization of Marine Macroalgae Derived Silver Nanoparticles and their Colorimetric Sensing of Hydrogen Peroxide. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yugay, Y.A.; Usoltseva, R.V.; Silant, V.E.; Egorova, A.E.; Karabtsov, A.A.; Kumeiko, V.V.; Ermakova, S.P.; Bulgakov, V.P.; Shkryl, Y.N. Synthesis of Bioactive Silver Nanoparticles using Alginate, Fucoidan and Laminaran from Brown Algae as a Reducing and Stabilizing Agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 116547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, S.; Wang, B.; Dutta, P. Nanoparticle Processing: Understanding and Controlling Aggregation. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 279, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Lama-Calvente, D.; Fernández-Rodríguez, M.J.; Ballesteros, M.; Ruiz-Salvador, Á.R.; Raposo, F.; García-Gómez, J.C.; Borja, R. Turning an Invasive Alien Species into a Valuable Biomass: Anaerobic Digestion of Rugulopteryx okamurae After Thermal and New Developed Low-Cost Mechanical Pretreatments. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Anta, T.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Mazón, J.; Dominguez, H. Microwave-Assisted Hydrothermal Processing of Rugulopteryx okamurae. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hortas, L.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Mazón, J.; Domínguez, H.; Torres, M.D. Relevance of Drying Treatment on the Extraction of High Valuable Compounds from Invasive Brown Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae. Algal Res. 2023, 69, 102917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Cervera, M.A.; De Burgos-Navarro, I.; Chileh-Chelh, T.; Belarbi, E.; Álvarez-Corral, M.; Carmona-Fernández, M.; Ezzaitouni, M.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L. The Agronomic Potential of the Invasive Brown Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae: Optimisation of Alginate, Mannitol, and Phlorotannin Extraction. Plants 2024, 13, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, I.; Felix, M.; Bengoechea, C. Sustainable Biocomposites Based on Invasive Rugulopteryx okamurae Seaweed and Cassava Starch. Sustainability 2024, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, I.; Felix, M.; Bengoechea, C. Feasibility of Invasive Brown Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae as Source of Alginate: Characterization of Products and Evaluation of Derived Gels. Polymers 2024, 16, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj, R.N.; Mellinas, C.; Jiménez, A.; Bordehore, C.; Garrigós, M.C. Invasive Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae: A Potential Source of Bioactive Compounds with Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián-Lloret, V.; Cartan-Moya, S.; Martínez-Sanz, M.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Calvo, M.V.; López-Rubio, A.; Martínez-Abad, A. Characterization of the Invasive Macroalgae Rugulopteryx okamurae for Potential Biomass Valorisation. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Granados, J.J.; Jiménez-Hierro, M.J.; Zuasti, E.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Puertas, B.; Zarraonaindia, I.; Hachero-Cruzado, I.; Cantos-Villar, E. Biochemical Characterization and Potential Valorization of the Invasive Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Catalá, T.S.; García-Márquez, J.; Speidel, L.G.; Arijo, S.; Cornelius Kunz, N.; Geisler, C.; Figueroa, F.L. Molecular Diversity and Biochemical Content in Two Invasive Alien Species: Looking for Chemical Similarities and Bioactivities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Lama-Calvente, D.; Fernández-Rodríguez, M.J.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; Borja, R. Process Optimization of the Extraction of Reducing Sugars and Total Phenolic Compounds from the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae by Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Algal Res. 2024, 80, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghel, R.S.; Reddy, C.R.K.; Singh, R.P. Seaweed-Based Cellulose: Applications, and Future Perspectives. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 267, 118241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Viñas, M.; González-Ballesteros, N.; Torres, M.D.; López-Hortas, L.; Vanini, C.; Domingo, G.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Domínguez, H. Efficient Extraction of Carrageenans from Chondrus crispus for the Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Formulation of Printable Hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Prado-López, S.; Lastra, M.; Grimaldi, M.; Cavazza, A.; Nasi, L.; Salviati, G.; Bigi, F. Macroalgae to Nanoparticles: Study of Ulva lactuca Role in Biosynthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles and of their Cytotoxicity on Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Mat. Scie Eng. C 2019, 97, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Yin, J.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Applications of Infrared Spectroscopy in Polysaccharide Structural Analysis: Progress, Challenge and Perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balquinta, M.L.; Dellatorre, F.G.; Andrés, S.C.; Lorenzo, G. Effect of pH and Seaweed (Undaria pinnatifida) Meal Level on Rheological and Antioxidant Properties of Model Aqueous Systems. Algal Res. 2022, 62, 102629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziveleka, L.; Tammam, M.A.; Tzakou, O.; Roussis, V.; Ioannou, E. Metabolites with Antioxidant Activity from Marine Macroalgae. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood Ansari, S.; Saquib, Q.; De Matteis, V.; Awad Alwathnani, H.; Ali Alharbi, S.; Ali Al-Khedhairy, A. Marine Macroalgae Display Bioreductant Efficacy for Fabricating Metallic Nanoparticles: Intra/Extracellular Mechanism and Potential Biomedical Applications. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2021, 2021, 5985377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.C.; Reddy, C.; Balar, N.; Suthar, P.; Gajaria, T.; Gadhavi, D.K. Assessment of the Nutritive, Biochemical, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential of Eight Tropical Macro Algae Along Kachchh Coast, India as Human Food Supplements. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2018, 27, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Anjali, R.; Jeneeta, S.; Mohandoss, S.; Keerthana, D.; Shin, I.; You, S.; Prabhu, N.M. An Effective Bio-Inspired Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles using Caulerpa sertularioides and Investigating their Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 46, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, N.A.I.M.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Timmiati, S.N.; Basri, S.; Karim, N.A. Exploration of Biogenic Pt Nanoparticles by using Agricultural Waste (Saccharum officinarum L. Bagasse Extract) as Nanocatalyst for the Electrocatalytic Oxidation of Methanol. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 42, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshi, A.; Foroughi, M.R.; Monshi, M.R. Modified Scherrer Equation to Estimate More Accurately Nano-Crystallite Size using XRD. World J. Nano Sci. Eng. 2012, 2, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; González-Rodríguez, J.B.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C.; Lastra, M. New Application of Two Antarctic Macroalgae Palmaria decipiens and Desmarestia menziesii in the Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles. Polar Sci. 2018, 15, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Prado-López, S.; Rodríguez-González, J.B.; Lastra, M.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles using Brown Algae Cystoseira baccata: Its Activity in Colon Cancer Cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 153, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | [Extract] (mg/mL) | [Au] (mM) | [Ag] (mM) | [Pt] (mM) | T (°C) | t (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au@RO | 6.67 | 0.33 | - | - | 30 | 24 |

| Ag@RO | 10 | - | 0.17 | - | 100 | 2 |

| Pt@RO | 1 | - | - | 0.4 | 100 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira Pinto, E.; González-Ballesteros, N.; Rodríguez-Argüelles, M.C. Exploiting the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae for the Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and an Investigation of Their Antioxidant Properties. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120479

Pereira Pinto E, González-Ballesteros N, Rodríguez-Argüelles MC. Exploiting the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae for the Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and an Investigation of Their Antioxidant Properties. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):479. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120479

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira Pinto, Estefania, Noelia González-Ballesteros, and María Carmen Rodríguez-Argüelles. 2025. "Exploiting the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae for the Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and an Investigation of Their Antioxidant Properties" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120479

APA StylePereira Pinto, E., González-Ballesteros, N., & Rodríguez-Argüelles, M. C. (2025). Exploiting the Invasive Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae for the Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles and an Investigation of Their Antioxidant Properties. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 479. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120479