ScillyHAB: A Multi-Disciplinary Survey of Harmful Marine Phytoplankton and Shellfish Toxins in the Isles of Scilly: Combining Citizen Science with State-of-the-Art Monitoring in an Isolated UK Island Territory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

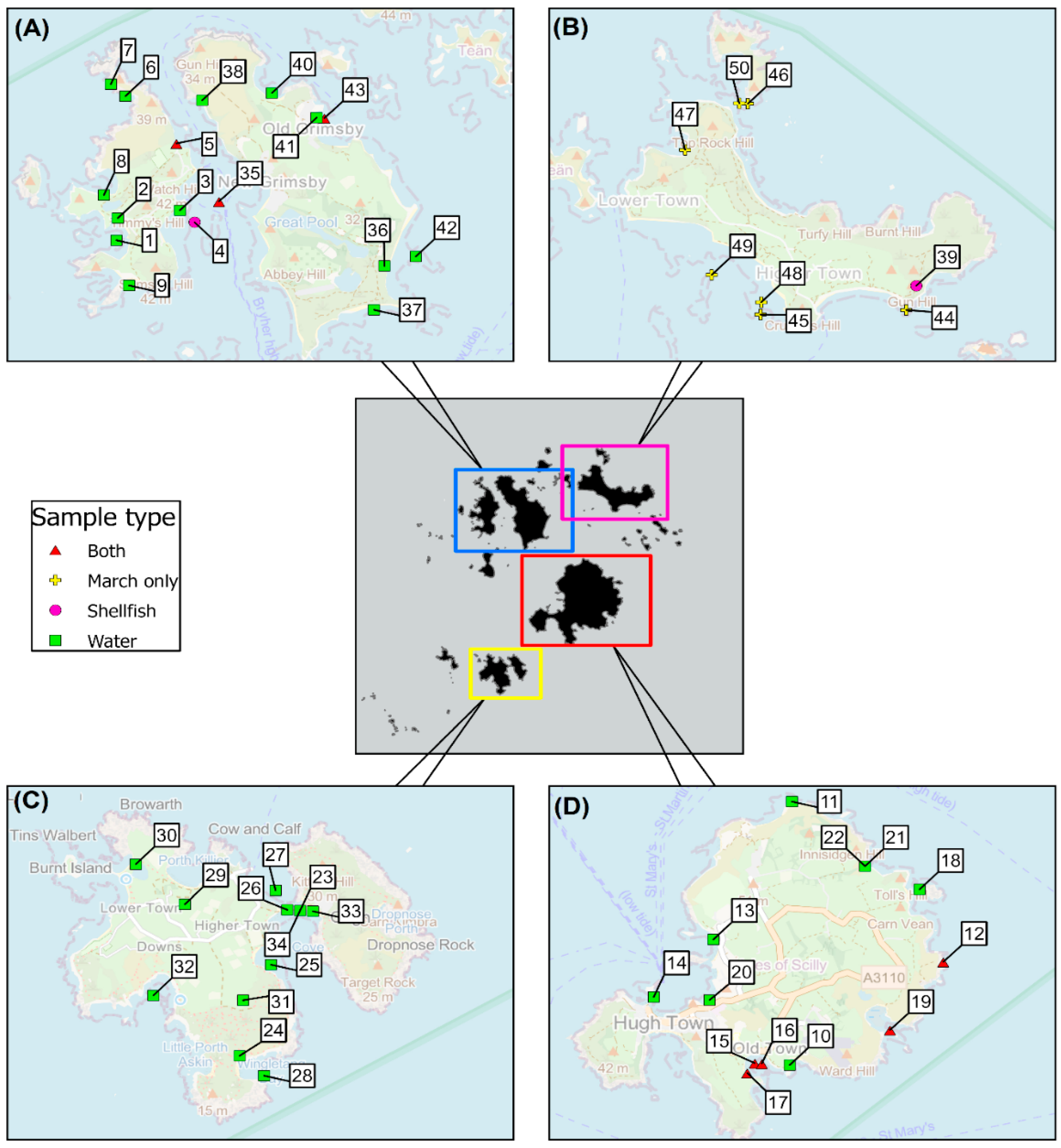

2.1. Samples and Sampling Programme

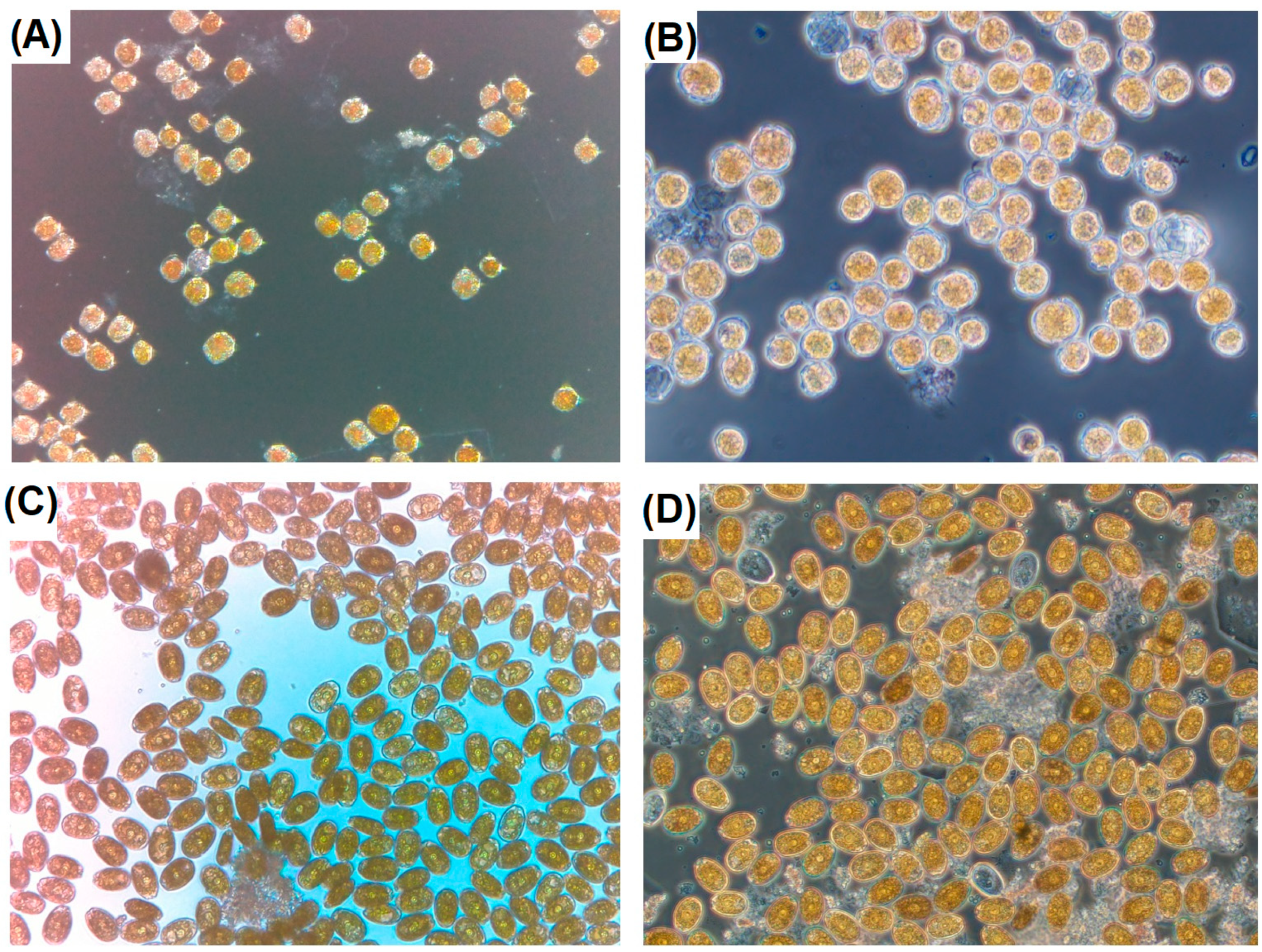

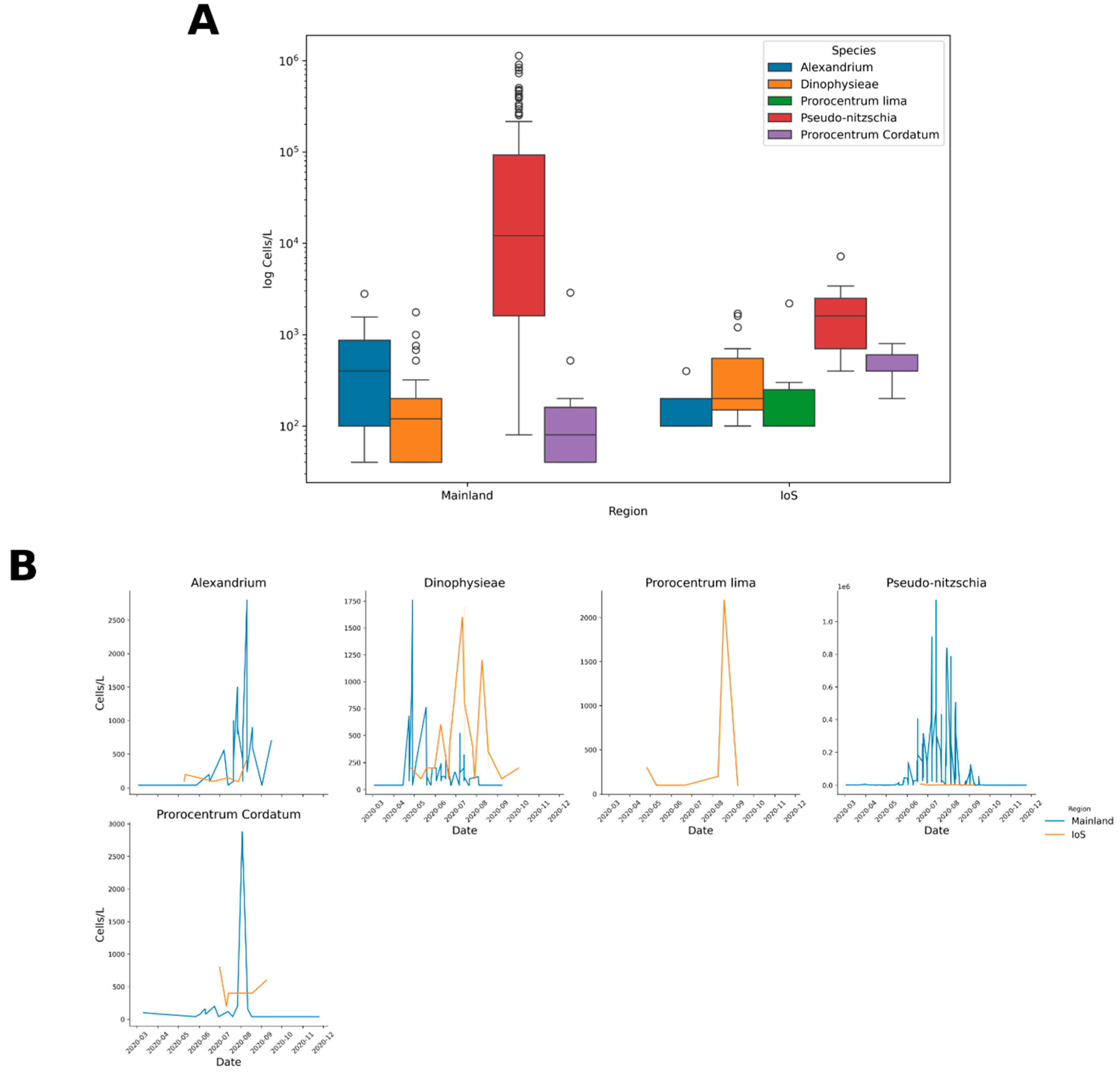

2.2. Seawater—Microscopy

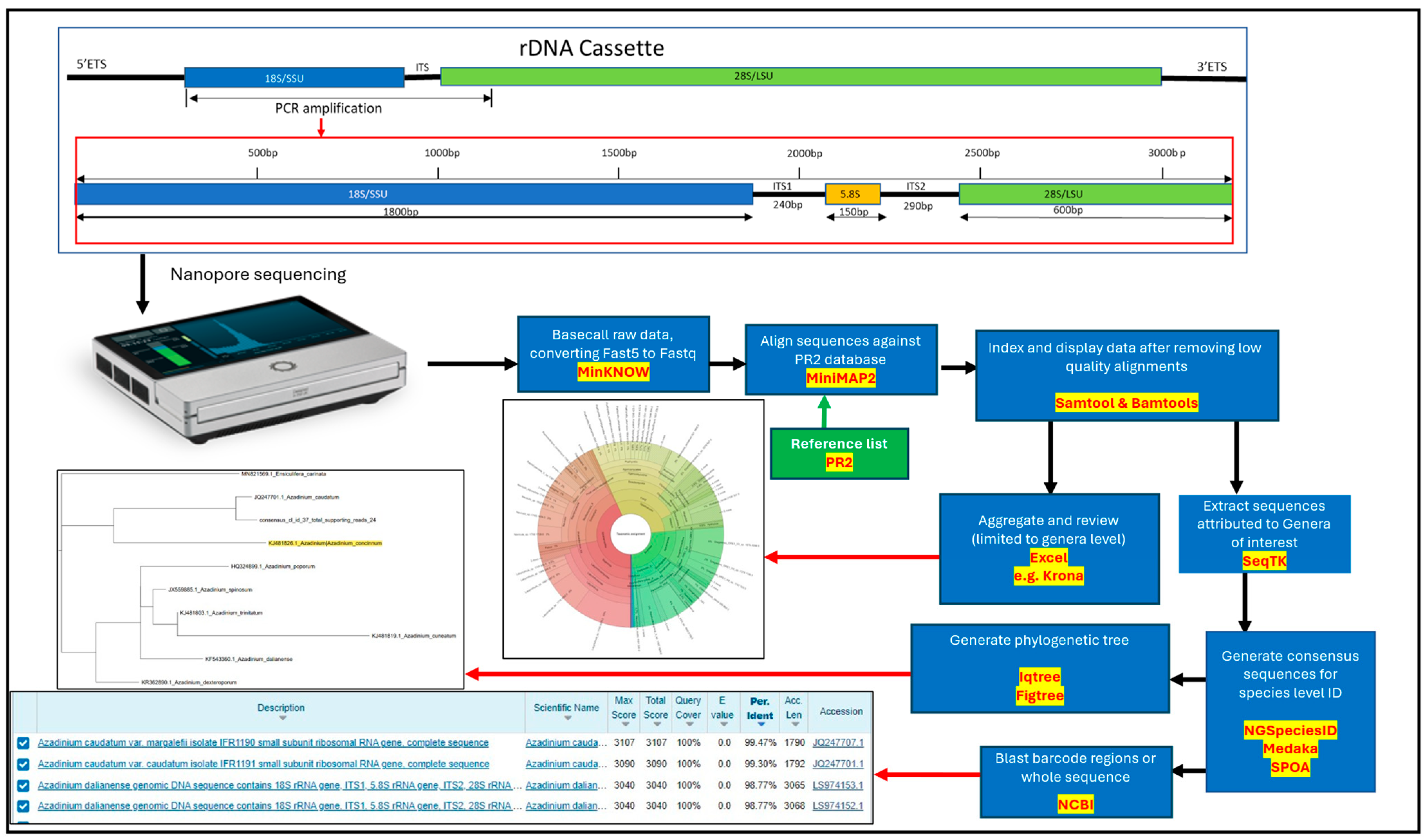

2.3. Molecular Analysis of Water Samples

2.3.1. Alignment with PR2 Database

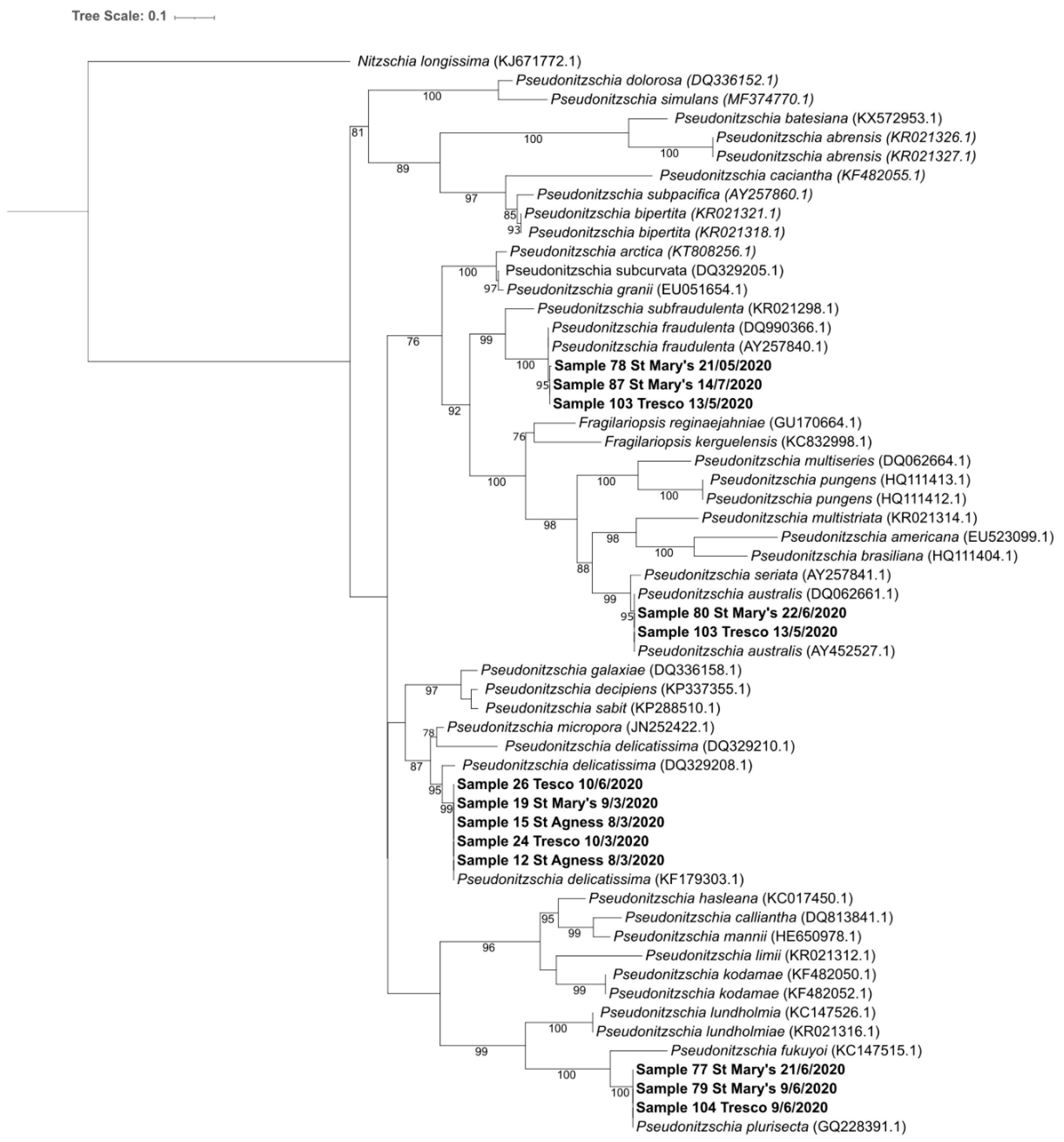

2.3.2. Consensus Sequences

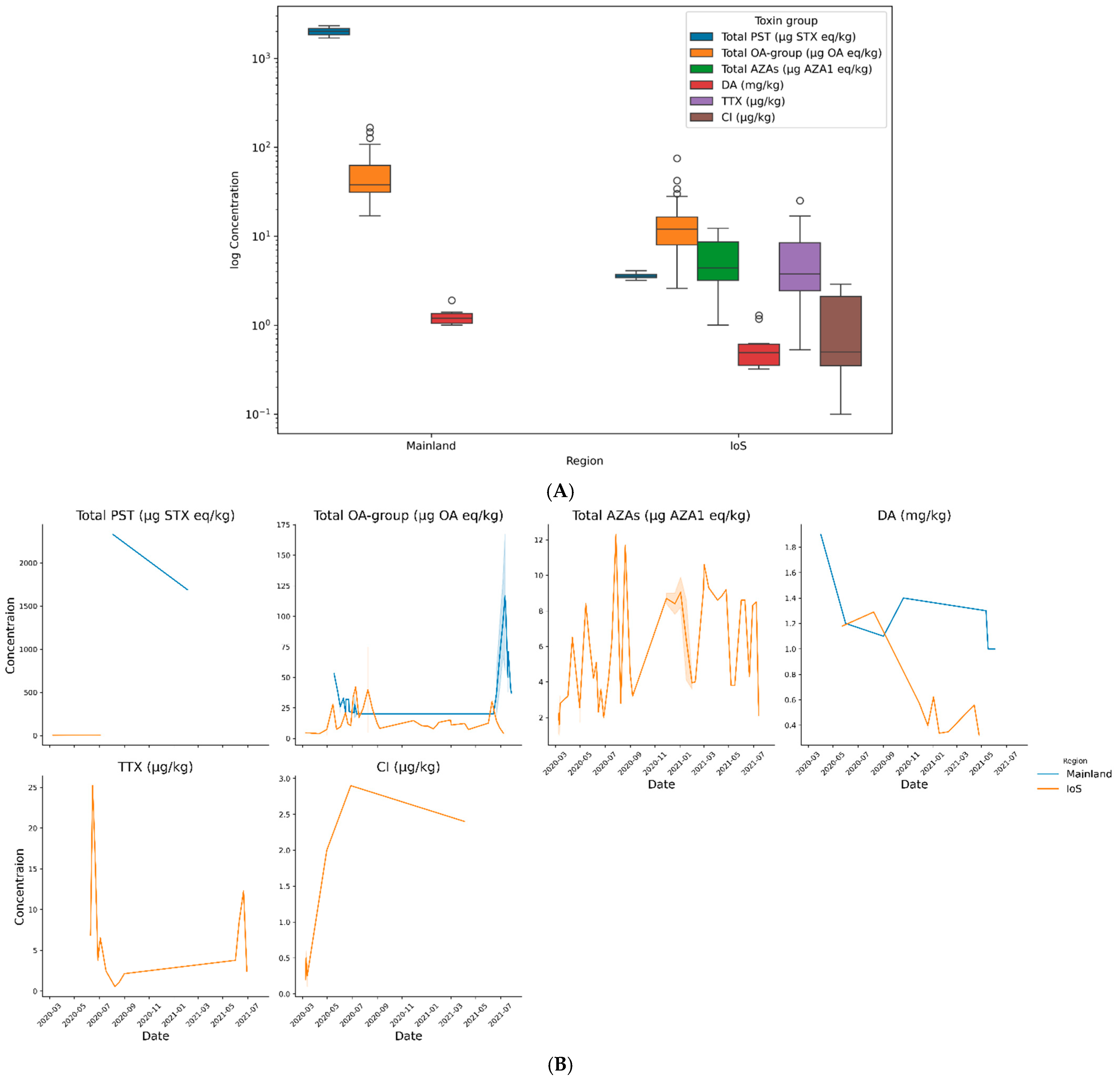

2.4. Shellfish Toxins

2.4.1. Bivalve Molluscs

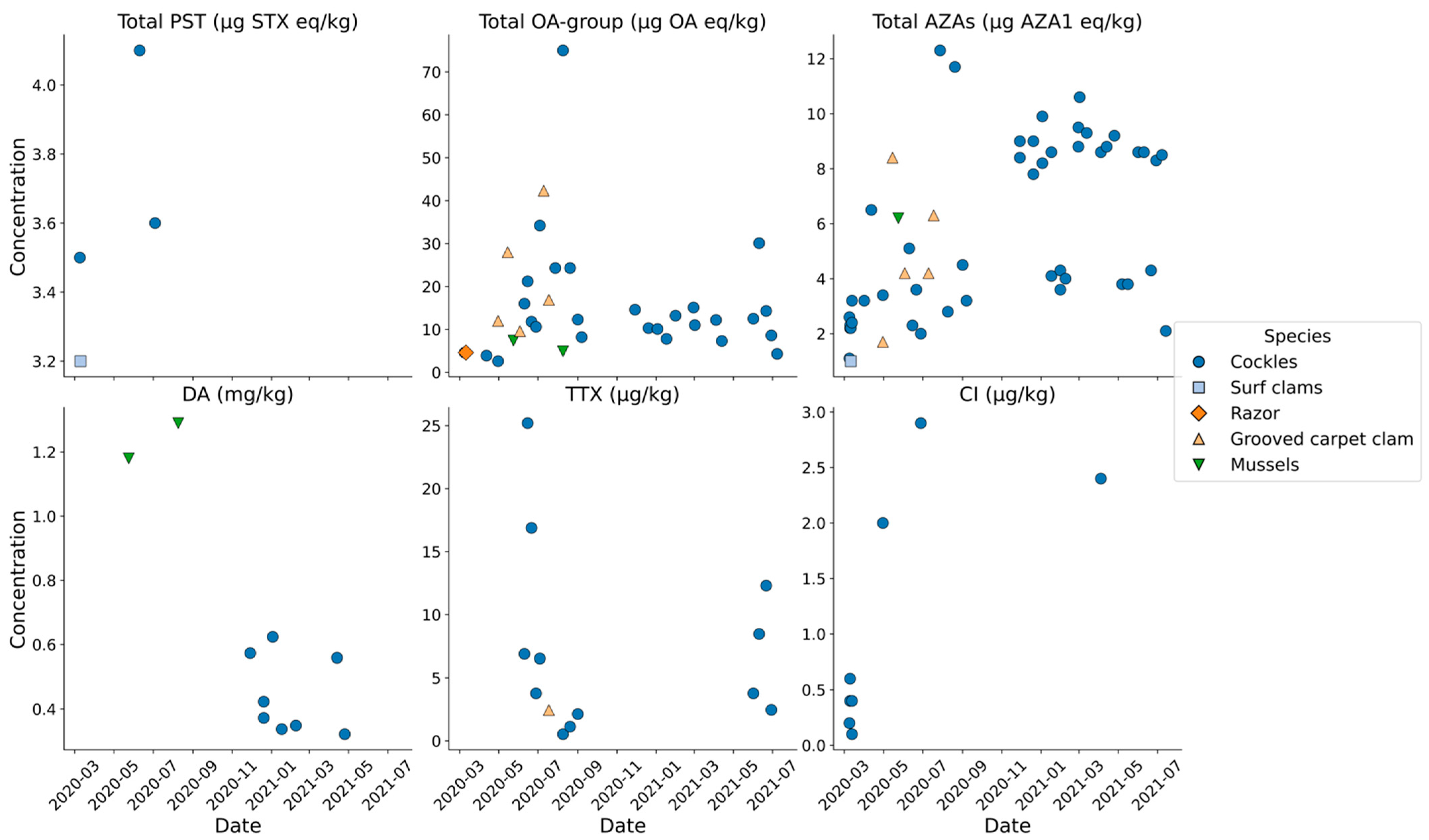

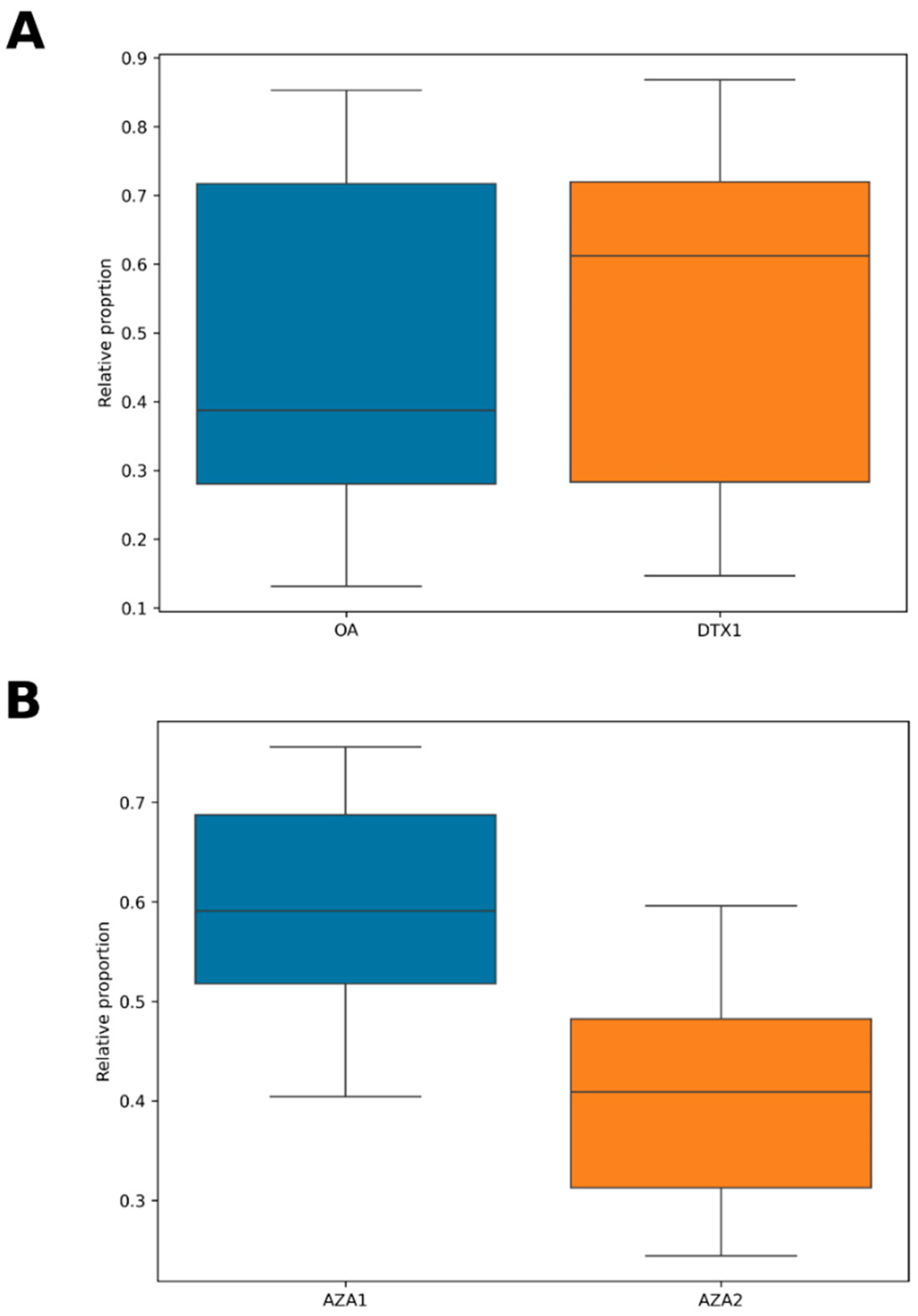

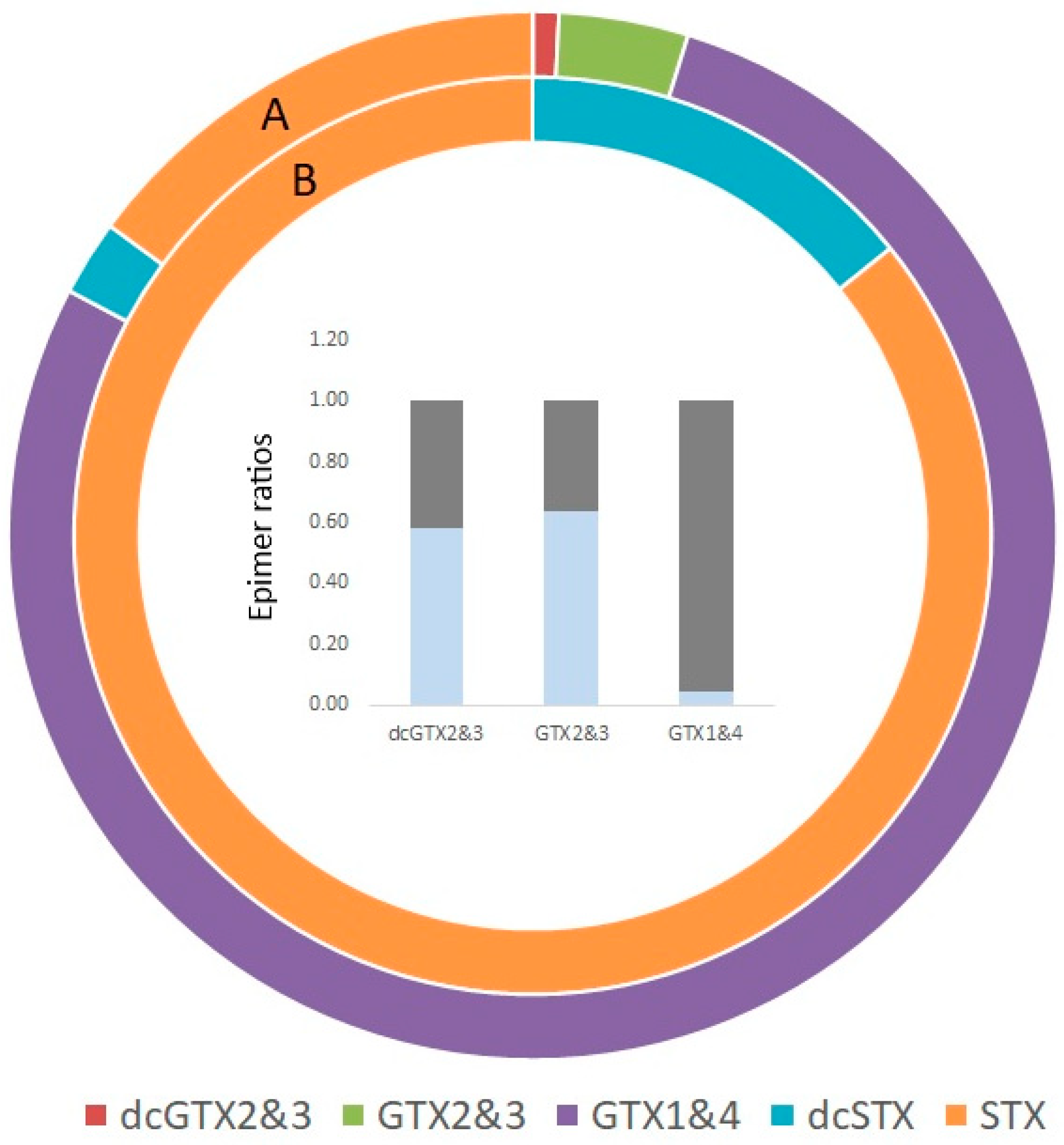

Chemical Analysis

Lateral Flow Assays

2.4.2. Echinoderms

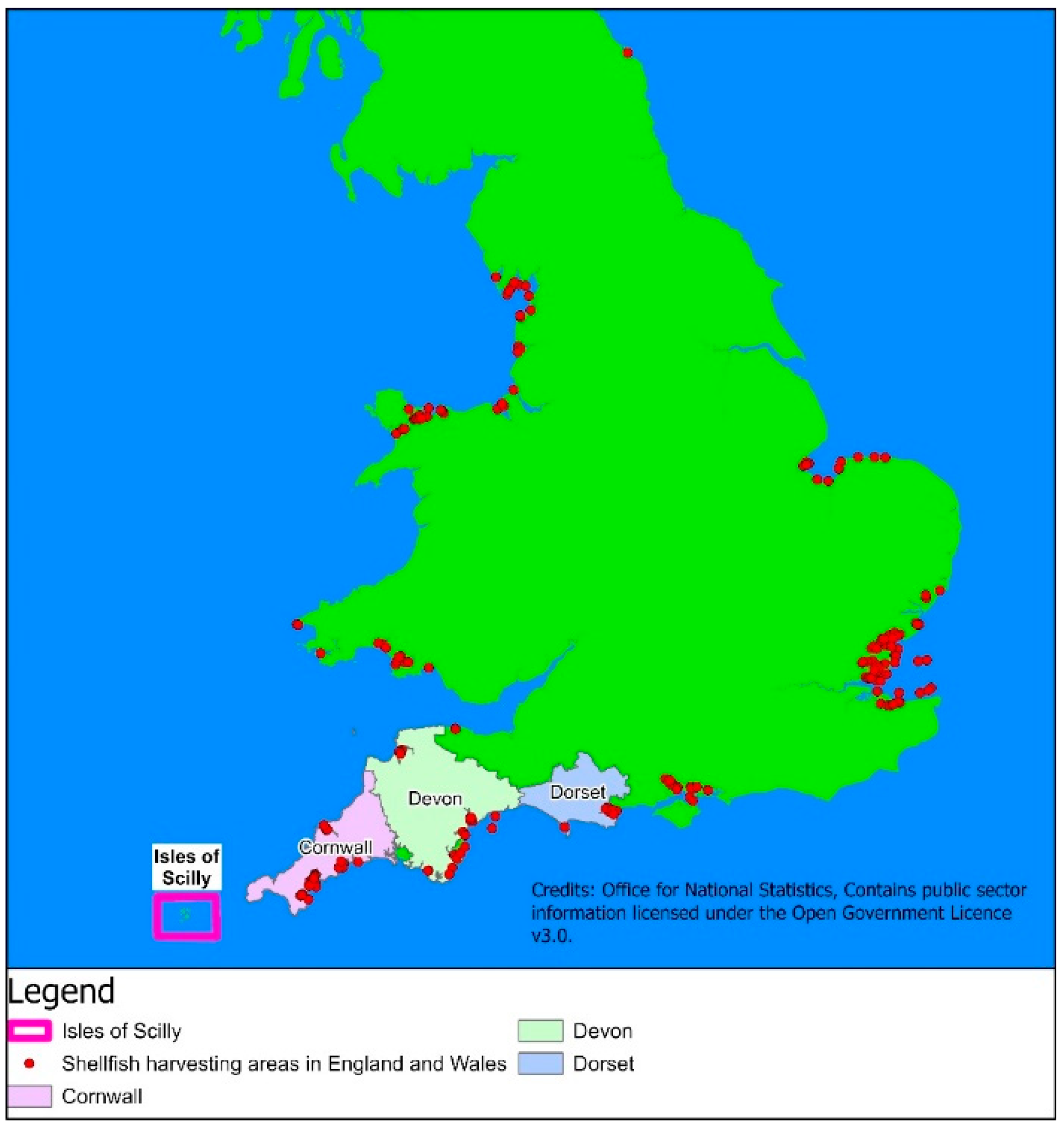

2.5. Other Regions

3. Discussion

3.1. Citizen Science

3.2. Seawater Analysis

3.3. Pseudo-nitzschia sp.

3.4. Alexandrium sp.

3.5. Azadinium or Amphidinium

3.6. Dinophysis sp.

3.7. Prorocentrum sp.

3.8. Coolia sp.

3.9. Kareniaceae

3.10. Karlodinium sp.

3.11. Karenia sp.

3.12. Dictyochyceans

3.13. Noctiluca

3.14. Indeterminate Dinoflagellates

3.15. Shellfish and Biotoxins

3.15.1. Bivalve Molluscs

3.15.2. Echinoderms

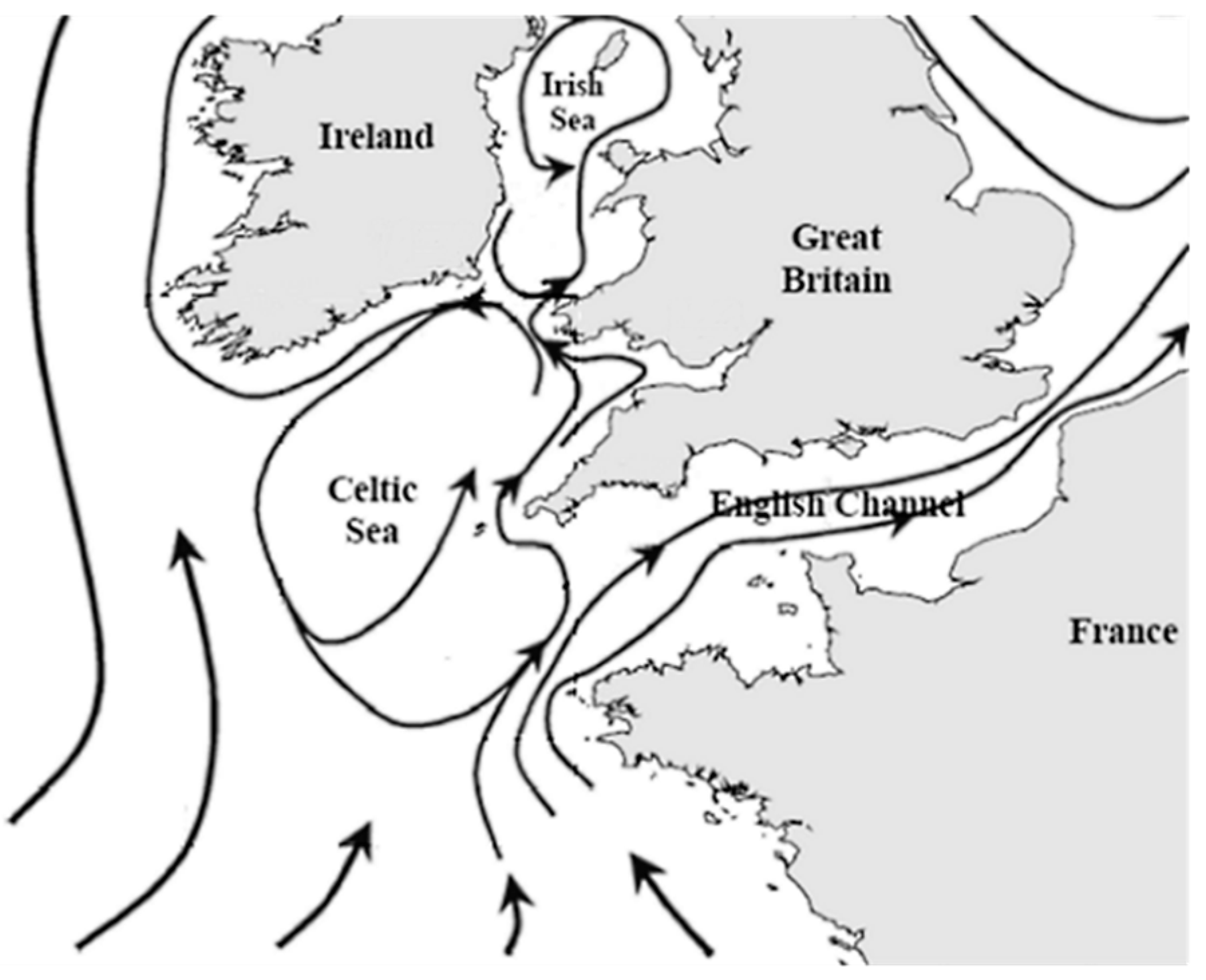

3.16. Links to Mainland

3.17. Future Human Health Protection in the Isles of Scilly

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Reagents and Standards

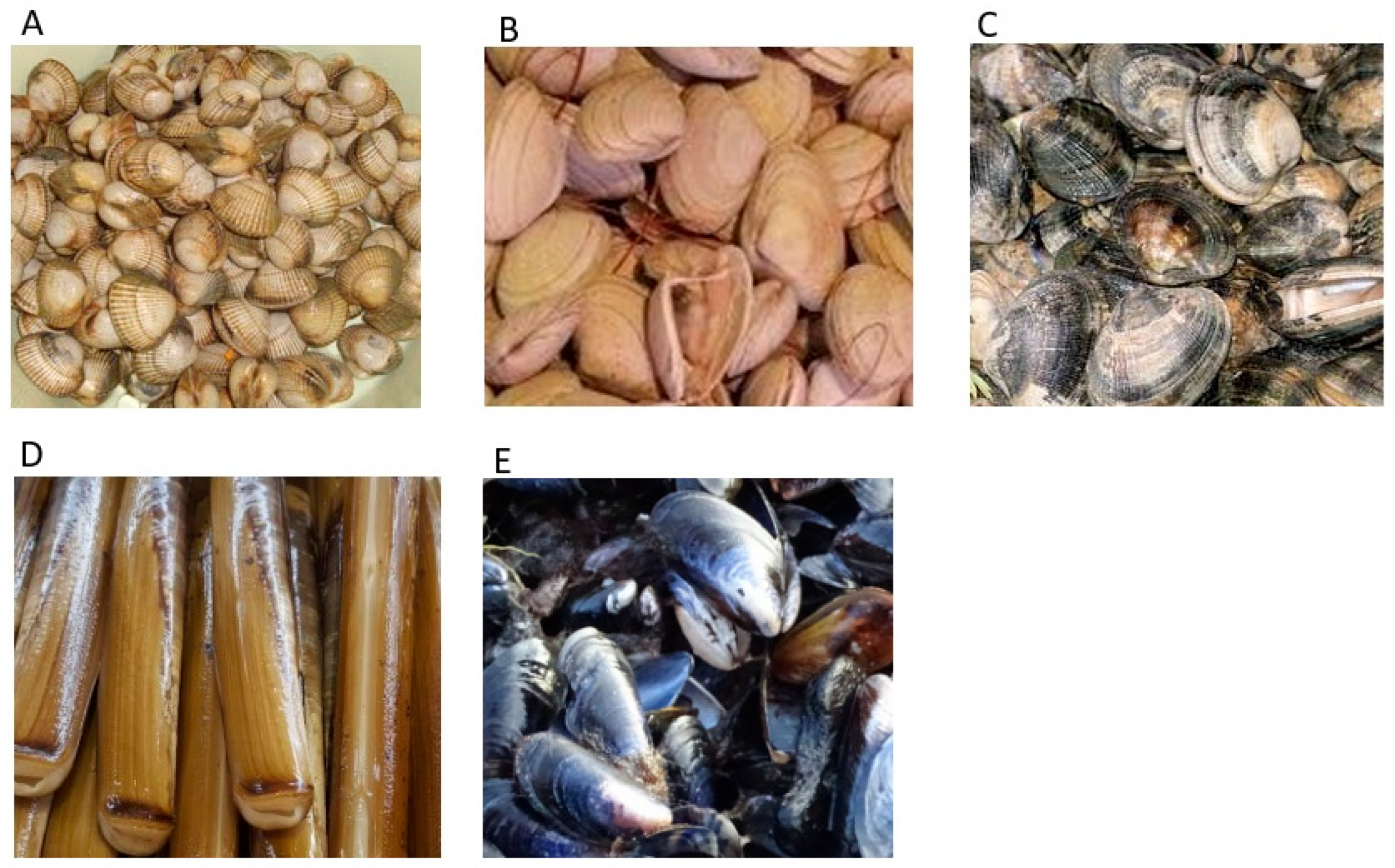

5.2. Samples

5.3. Seawater Analysis

5.4. Molecular Analysis of Water Samples

5.4.1. Sample Preparation and DNA Sequencing

- FWD: 5′ TTTCTGTTGGTGCTGATATTGCGCTTGTCTCAAA GATTAAGCCATGC 3′

- REV: 5′ ACTTGCCTGTCGCTCTATCTTCCCTTGGTCCGTG TTTCAAGA 3′

5.4.2. Bioinformatic Analysis of Molecular Data

Base Calling

Alignment to Reference Sequences

Generation of Consensus Sequences

Phylogenetic Analysis of Consensus Sequences

5.5. Shellfish Toxin Analysis

5.5.1. Chemical Assays

5.5.2. Immunoassays

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hallegraeff, G.M. Harmful algal blooms: A global overview. In Manual on Harmful Marine Microalgae; Hallegraeff, G.M., Anderson, D.M., Cembella, A.D., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1995; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Masó, M.; Garcés, E. Harmful microalgae blooms (HAB); problematic and conditions that induce them. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 53, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Cembella, A.D.; Hallegraeff, G.M. Progress in understanding harmful algal blooms: Paradigm shifts and new technologies for research, monitoring, and management. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2012, 4, 143–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Fleming, L.E.; Gowen, R.; Davidson, K.; Hess, P.; Backer, L.C.; Moore, S.K.; Hoagland, P.; Enevoldsen, H. Marine harmful algal blooms human health wellbeing: Challenges opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2016, 96, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, G.C.; Casewell, N.R.; Ellioott, C.T.; Harvey, A.L.; Jamieson, A.G.; Strong, P.N.; Turner, A.D. Friends of Foes? Emerging impacts of biological toxins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 1538, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.D.; Lewis, A.M.; Bradley, K.; Maskrey, B.H. Marine invertebrate interactions with Harmful Algal Blooms—Implications for One Health. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 186, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, D.J.; Hart, R.J.; Matthews, P.A.; Howden, M.E.H. Nonprotein neurotoxins. Clin. Toxicol. 1981, 18, 813–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricelj, V.M.; Kuenstner, S.H. Effects of the “Brown Tide” on the Feeding Physiology and Growth of Bay Scallops and Mussels. In Novel Phytoplankton Blooms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, J.H. The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2002, 10, 113–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, A.; Smith, B.C.; Wikfors, G.H.; Quilliam, M. Grazing on toxic Alexandrium fundyense resting cysts and vegetative cells by the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica). Harmful Algae 2006, 5, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glibert, P.M.; Anderson, D.M.; Gentien, P.; Granéli, E.; Sellner, K.G. The global, complex phenomena of harmful algal blooms. Oceanography 2005, 18, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smayda, T.J. Bloom dynamics: Physiology, behavior, trophic effects. Limonaol. Oceanogr. 1997, 42, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantiani, L.; Llorca, M.; Sanchís, J.; Farré, M.; Barceló, D. Emerging food contaminants: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 398, 2413–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattan, L.M.; Holobaugh, S.; Morris, J.G. Harmful algal blooms and public health. Harmful Algae 2016, 57, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway, S.E. A Review of the Effects of Algal Blooms on Shellfish and Aquaculture. J. World Aquac. Soc. 1990, 21, 65–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Commission Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for food of animal origin. Off J. Eur. Comm. 2004, L226, 22–82. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Commission regulation (EC) no 2074/2005 European union commission. Off J. Eur. Union 2005, L338, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Commission regulation (EU) No 15/2011 of 10 January 2011 amending regulation (EC) No 2074/2005 as regards recognised testing methods for detecting marine biotoxins in live bivalve molluscs. Off J. Eur. Union 2011, 54, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anon. Commission regulation (EU) 2017/1980 of 31 October 2017 amending Annex IIIto regulation (EC) No 2074/2005 as regards paralytic shellfish poison (PSP) detection method. Off J. Europ. Union 2017, L28, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Witte, B.; Coleman, B.; Bekaert, K.; Boitsov, S.; Bothelo, M.J.; Castro-Jimenez, J.; Duffy, C.; Habedank, F.; McGovern, E.; Parmentier, K.; et al. Threshold values on environmental chemical contaminants in seafood in the European Economic Area. Food Control 2022, 138, 108978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dolah, F.M. Marine algal toxins: Origins, health effects, and their increased occurrence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000, 108, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, J.; Hoogenboom, R.L.A.P.; Hendriksen, P.J.M.; Bodero, M.; Bovee, T.F.H.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M.; Gerssen, A. Marine biotoxins and associated outbreaks following seafood consumption: Prevention and surveillance in the 21st century. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 15, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Opinion Marine Biotoxins in Shellfish Saxitoxin Group. Scientific opinion of the panel on contaminants in the food chain. EFSAJ 2009, 1019, 1–76.

- Llewellyn, L.; Negri, A.; Robertson, A. Paralytic shellfish toxins in tropical oceans. Toxin Rev. 2006, 25, 159–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Li, Z.; Réveillon, D.; Rovillon, G.A.; Mertens, K.N.; Hess, P.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, D.; et al. Centrodinium punctatum (Dinophyceae) produces significant levels of saxitoxin and related analogs. Harmful Algae 2020, 100, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, S.; Gunnarsson, T.; Gunnarsson, K.; Clarke, D.; Turner, A.D. First detection of paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) toxins in Icelandic mussels (Mytilus edulis): Links to causative phytoplankton species. Food Control 2013, 31, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.S.; Hubbard, K.A.; Lundholm, N.; Montresor, M.; Leaw, C.P. Pseudo-nitzschia, Nitzschia, and domoic acid: New research since 2011. Harmful Algae 2018, 79, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.S.; Bird, C.J.; Freitas, A.S.W.; de Foxall, R.; Gilgan, M.; Hanic, L.A.; Johnson, G.R.; McCulloch, A.W.; Odense, P.; Pocklington, R.; et al. Pennate diatom Nitzschia pungens as the primary source of domoic acid a toxin in shellfish from Eastern Prince Edward Island Canada. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1989, 46, 1203–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, T.M.; Bédard, L.; Kosatsky, T.; Hockin, J.C.; Todd, E.C.D.; Remis, R.S. An outbreak of toxic encephalopathy caused by eating mussels contaminated with domoic acid. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 322, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; Benford, D.; Boobis, A.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cravedi, J.; Di Domenico, A.; Doerge, D.; Dogliotti, E.; Edler, L.; Farmer, P.; et al. Marine biotoxins in shellfish—Domoic acid Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain adopted on 2 July 2009. EFSAJ 2009, 1181, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, K.A.; Robertson, A. Domoic acid and human exposure risks: A review. Toxicon 2010, 56, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelong, A.; Hégaret, H.; Soudant, P.; Bates, S.S. Pseudo-nitzschia (Bacillariophyceae) species, domoic acid and amnesic shellfish poisoning: Revisiting previous paradigms. Phycologia 2012, 51, 168–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnan, E.; Kraberg, A.; Fraser, S.; Brown, L.; Hughes, S.; Wiltshire, K.H. Diversity and seasonality of Pseudo-nitzschia (peragallo) at two North Sea time-series monitoring sites. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2015, 69, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pazos, Y.; Ar’evalo, F.; Correa, J.; Covadonga, S. Initiation, maintenance and dissipation of a toxic bloom of Dinophysis acuminata and Pseudonitzschia australis: A comparison of the ria of Arousa and ria of Pontevedra. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Harmful Algae, Florianópolis, Brazil, 9–14 October 2016; OS10002: Abstract book International Conference for Harmful Algae. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Yasumoto, T.; Oshima, Y.; Sugawara, W.; Fukuyo, Y.; Oguri, H.; Igarishi, T.; Fujita, N. Identification of Dinophysis fortii as the causative organism of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Sci. Fish 1980, 46, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumoto, T.; Murata, M.; Oshima, Y.; Matsumoto, G.K.; Clardy, J. Diarrhetic shellfish poisoning. In Seafood Toxins; Regalis, E.P., Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Reguera, B.; Velo-Suarez, L.; Raine, R.; Park, M.G. Harmful Dinophysis species: A review. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, B.; Riobo, P.; Rodriguez, F.; Diaz, P.A.; Pizarro, G.; Paz, B.; Franco, J.M.; Blanco, J. Dinophysis toxins: Causative organisms, distribution and fate in shellfish. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 394–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Yasumoto, T. Identification of okadaic acid as a toxic component of a marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 1982, 48, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachibana, K.; Scheuer, P.J.; Tsukitani, Y.; Kikuchi, H.; Van Engen, D.; Clardy, J.; Gopichand, Y.; Schmitz, F.J. Okadaic acid a cytotoxic polyether from two marine sponges of the genus Halichondria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103, 2469–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Marr, J.; Defreitas, A.S.W.; Quilliam, M.A.; Walter, J.A.; Wright, J.L.C.; Pleasance, S. New diol esters isolated from cultures of the dinoflagellates Prorocentrum lima and Prorocentrum concavum. J. Nat. Prod. 1992, 55, 1631–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, N.; Robin, C.; Kwiatkowska, R.; Beck, C.; Mellon, D.; Edwards, P.; Turner, J.; Nicholls, P.; Fearby, G.; Lewis, D.; et al. Outbreak of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning associated with consumption of mussels, United Kingdom, May to June 2019. Euro Surveill 2019, 24, 1900513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, R.W.; Baden, D.; Fleming, L.E. Brevetoxins. In Assessment and Management of Biotoxin Risks in Bivalve Molluscs; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; Volume 551, pp. 51–98. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific Opinion on marine biotoxins in shellfish—Emerging toxins: Brevetoxin group. EFSAJ 2010, 8, 1677. [CrossRef]

- Arnich, N.; Abadie, E.; Amzil, Z.; Dechraoui Bottein, M.-Y.; Comte, K.; Chaix, E.; Delcourt, N.; Hort, V.; Mattei, C.; Molgo, J.; et al. Guidance level for brevetoxins in French shellfish. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific opinion on marine biotoxins in shellfish-cyclic imines (spirolides gymnodimines pinnatoxins and pteriatoxins). EFSAJ 2010, 8, 1628–1666. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, A.; Chapela, M.-J.; Atanassova, M.; Vietes, J.M.; Cabado, A.G. Cyclic imines: Chemistry and mechanism of action: A review. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1817–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambla-Alegre, M.; Miles, C.O.; de la Inglesia, P.; Fernandez-Tejedor, M.; Jacobs, S.; Sioen, I.; Verbeke, W.; Samdal, I.A.; Sandvik, M.; Barbosa, V.; et al. Occurrence of cyclic imines in European commercial seafood and consumers risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2018, 161, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.D.; Higgins, C.; Higman, W.; Hungerford, J. Potential threats posed by Tetrodotoxins in UK waters: Examination of detection methodology used in their control. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 7357–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Powell, A.; Schofield, A.; Lees, D.N.; Baker-Austin, C. Detection of the pufferfish toxin Tetrodotoxin in European bivalves, England, 2013–2014. Eurosurveillance 2015, 20, 21009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.D.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Coates, L.; Bickerstaff, L.; Milligan, S.; O’Neill, A.; Faulkner, D.; McEneny, H.; Baker-Austin, C.; Lees, D.N.; et al. Detection of Tetrodotoxin Shellfish Poisoning (TSP) toxins and causative factors in bivalve molluscs from the UK. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Knutsen, H.K.; Alexander, J.; Barregård, L.; Bignami, M.; Brüschweiler, B.; Ceccatelli, S.; Cottrill, B.; Dinovi, M.; Edler, L.; et al. Scientific opinion on the risks for public health related to the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX) and TTX analogues in marine bivalves and gastropods. EFSAJ 2017, 15, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katikou, P.; Gokbulut, C.; Kosker, A.R.; Campas, M.; Ozogul, F. An updated review of Tetrodotoxin and its pecularities. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, K.; Baker, C.; Higgins, C.; Higman, W.; Swan, S.; Veszelovszki Turner, A.D. Potential threats posed by new of emerging marine biotoxins in UK waters and examination of detection methodologies used for their control: Cyclic imines. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 7067–7112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, R.P.; O’Neill, A.; Dean, K.J.; Turner, A.D.; Maskrey, B.H. Detection of cyclic imines Pinnatoxin G, 13-Desmethyl spirolide C and 20-methyl spirolide G in bivalve molluscs from Great Britain. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli, P.; Salerno, B.; Bordin, P.; Peruzzo, A.; Orsini, M.; Arcangeli, G.; Barco, L.; Losasso, C. Tetrodotoxin in live bivalve molluscs from Europe: Is it to be considered an emerging concern for food safety? Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 21, 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Karlson, B.; Wulff, A.; Kudela, R.; Trick, C.; Asnaghi, V.; Berdalet, E.; Cochlan, W.; Davidson, K.; De Rijcke, M.; et al. Future HAB science: Directions and challenges in a changing climate. Harmful Algae 2020, 91, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilliam, M.A.; Xie, M.; Hardstaff, W.R. Rapid extraction and cleanup for liquid chromatography determination of domoic acid in unsalted seafood. J. AOAC Int. 1995, 78, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland-Pilgrim, S.; Swan, S.C.; O’Neill, A.; Johnson, S.; Coates, L.; Stubbs, P.; Dean, K.; Parks, R.; Harrison, K.; Teixeira Alves, M.; et al. Variability of Amnesic Shellfish Toxin and Pseudo-nitzschia occurrence in bivalve molluscs and water samples–Analysis of ten years of the official control monitoring programme. Harmful Algae 2019, 87, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.F.; Niedzwiadek, B.; Menard, C. Quantitative determination of paralytic shellfish poisoning toxins in shellfish using prechromatographic oxidation and liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection: Interlaboratory study. J. AOAC Int. 2004, 87, 8310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Hatfield, R.G.; Maskrey, B.H.; Algoet, M.; Lawrence, J.F. Evaluation of the New European Union Reference Method for Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in Shellfish: A Review of Twelve Years Regulatory Monitoring Using Pre-Column Oxidation LC-FLD. Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 113, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURLMB. European Reference Laboratory for Marine Biotoxins (EURLMB, 2013. EU Harmonised Standard Operating Procedure for Detection of Lipophilic Biotoxins by Mouse Bioassay version 5 January 2015. 2015. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/laboratorios/LNRBM/ARCHIVO2EU-Harmonised-SOP-LIPO-LCMSMS_Version5.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; O’Neill, A.; Maskrey, B.H.; Coates, L.; Alves, M.T.; Kelly, R.J.; Hatfield, R.G.; Rowland-Pilgrim, S.; Lewis, A.D.; Algoet, M.; et al. Variability and profiles of lipophilic toxins in bivalves from Great Britain during five and a half years of monitoring: Okadaic acid, dinophysis toxins and pectenotoxins. Harmful Algae 2018, 77, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; O’Neill, A.; Maskrey, B.H.; Coates, L.; Swan, S.C.; Teixeira Alves, M.; Kelly, R.J.; Hatfield, R.G.; Rowland-Pilgrim, S.J.; Lewis, A.M.; et al. Variability and profiles of lipophilic toxins in bivalves from Great Britain during five and a half years of monitoring: Azaspiracids and yessotoxins. Harmful Algae 2019, 87, 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, R.G.; Bean, T.; Turner, A.D.; Lees, D.N.; Lowther, J.; Lewis, A.; Baker-Austin, C. Development of a TaqMan qPCR assay for detection of Alexandrium spp. and application to harmful algal bloom monitoring. Toxicon X 2019, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, R.G.; Batista, F.M.; Bean, T.P.; Fonseca, V.G.; Santos, A.; Turner, A.D.; Lewis, A.; Dean, K.J.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. The Application of Nanopore Sequencing Technology to the Study of Dinoflagellates: A Proof of Concept Study for Rapid Sequence-Based Discrimination of Potentially Harmful Algae. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boundy, M.J.; Selwood, A.I.; Harwood, D.T.; McNabb, P.S.; Turner, A.D. Development of a sensitive and selective liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method for high throughput analysis of paralytic shellfish toxins using graphitised carbon solid phase extraction. J. Chrom. A 2015, 1387, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.D.; McNabb, P.S.; Harwood, D.T.; Selwood, A.I.; Boundy, M.J. Single laboratory validation of a multitoxin LC-hydrophilic interaction LC-MS/MS method for quantitation of Paralytic Shellfish Toxins in bivalve shellfish. J. AOAC Int. 2015, 98, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Fong, S.Y.T.; Hungerford, J.; McNabb, P.S.; Boundy, M.J.; Harwood, D.T. Ultrahigh-performance hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry method for the determination of paralytic shellfish toxins and tetrodotoxin in mussels, oysters, clams, cockles and scallops: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2020, 103, 533–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Stubbs, B.; Coates, L.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Hatfield, R.G.; Lewis, A.M.; Rowland-Pilgrim, S.; O’Neil, A.; Stubbs, P.; Ross, S.; et al. Variability of paralytic shellfish toxin occurrence and profiles in bivalve molluscs from Great Britain from official control monitoring as determined by pre-column oxidation liquid chromatography and implications for applying immunochemical tests. Harmful Algae 2014, 31, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FSAI. The occurrence of marine biotoxins and risk of exposure to seafood consumers in Ireland. In Report of the Scientific Committee of the Food Safety Authority of Ireland; Publication of the Food Safety Authority of Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2016; Available online: https://www.fsai.ie (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Salas, R.; Clarke, D. Review of DSP toxicity in ireland: Long-term trend impacts, biodiversity and toxin profiles from a monitoring perspective. Toxins 2019, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, V.; Jourdan-da Silva, N.; Guillois, Y.; Marchal, J.; Krys, S. Food poisoning outbreaks linked to mussels contaminated with okadaic acid and ester dinophysistoxin-3 in France, June 2009. Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2011, 16, 20020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belin, C.; Soudant, D.; Amzil, Z. Three decades of data on phytoplankton and phycotoxins on the French coast: Lessons from REPHY and REPHYTOX. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, D.; Reimann, C.; Skarphagen, H. The comparative hydrochemistry of two granite islan aquifers: The Isles of Scilly, UK and the Hvaler Islands, Norway. Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 209, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, H.; Rogers, A. Tourism and the environment on the Isles of Scilly: Conflict and complementarity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1994, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.; Paver, L.F.C. Report on 2007 Isles of Scilly Zostera Marina Survey. Natural England Report. Microsoft Word—2007 IOS Report.doc. 2007. Available online: https://dassh.ac.uk (accessed on 16 June 2022).

- Leeney, R.H.; Witt, M.J.; Broderick, A.C.; Buchanan, J.; Jarvis, D.S.; Richardson, P.B.; Godley, B.J. Marine megavertebrates of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly: Relative abundance and distribution. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2012, 92, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly Du Bois, P.; Germain, P.; Rozet, M.; Solier, L. Water masses circulation and 2 residence time in the Celtic Sea and English Channel approaches, characterisation based 3 on radionuclides labelling from industrial releases. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Radioactivity in Environment, Monaco, 1–5 September 2002; pp. 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.; Carrillo, L.; Fernand, L.; Horsburgh, K.J.; Hill, A.E.; Young, E.F.; Medler, K.J. Observations of the physical structure and seasonal jet-like circulation of the Celtic Sea and St. George’s Channel of the Irish Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2003, 23, 533–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.M.; Coates, L.N.; Turner, A.D.; Percy, L.; Lewis, J. A review of the global distribution of Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) and comments on ecology and associated paralytic shellfish toxin profiles, with a focus on Northern Europe. J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exeter, O.M.; Axelsson, M.; Branscombe, J.; Broderick, A.; Hooper, T.; Morcom, S.; Russell, T.; Somerfield, P.J.; Sugar, K.; Webber, J.; et al. A synthesis of the current state of marine biodiversity knowledge in the Isles of Scilly, UK. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2024, 104, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.H.; Tett, P.B.; Argote-Espinoza, M.L.; Edwards, A.; Jones, K.L.; Savidge, G. Mixing and phytoplankton growth around an island in a stratified sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 1982, 1, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capuzzo, E.; Wright, S.; Bounch, P.; Collingridge, K.; Creach, V.; Pitois, S.; Stephens, D.; van der Kooij, J. Variability in structure and carbon content of plankton communities in autumn in the waters south-west of the UK. Prog. Oceanogr. 2022, 204, 102805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvin, J.-C.; Pezy, J.-P.; Baffreau, A. The English Channel: Becoming like the seas around Japan. In Oceanography Challenges to Future Earth; Komatsu, T., Ceccaldi, H.J., Yoshida, J., Prouzet, P., Henocque, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havel, J.E.; Kovalenko, K.E.; Thomaz, S.M.; Amalfitano, S.; Kats, L.B. Aquatic invasive species: Challenges for the future. Hydrobiologica 2015, 750, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchii, K.; Doi, H.; Minamoto, T. A novel environmental DNA approach to quantify the cryptic invasion of non-native genotypes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016, 16, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouet, K.; Jauzein, C.; Haerviot-Heath, D.; Hariri, S.; Laza-Martinez, A.; Lecadet, C.; Plus, M.; Seoane, S.; Sourisseau, M.; Lemee, R.; et al. Current distribution and potential expansion of the harmful benthic dinoflagellate Ostreopsis cf. Siamensis towards the warming waters of the Bay of Biscay, North-East Atlantic. Env. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 15406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.M.; Widdicombe, S.; Davey, J.J.; Somerfield, P.P.; Austen, M.C.V.; Warwick, R.M. The biogeography of islands: Preliminary results from a comparative study of the Isles of Scilly and Cornwall. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2009, 76, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.J.; Hatfield, R.G.; Lee, V.; Alexander, R.P.; Lewis, A.M.; Maskrey, B.H.; Teixeria Alves, M.; Hatton, B.; Coates, L.N.; Capuzzo, E.; et al. Multiple new paralytic shellfish toxin vectors in offshore North Sea benthos, a deep secret exposed. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.J.; Alexander, R.P.; Hatfield, R.G.; Lewis, A.M.; Coates, L.N.; Collin, T.; Taixeira Alves, M.; Lee, V.; Daumich, C.; Hicks, R.; et al. The common sunstar Crossaster papposus—A neurotoxic starfish. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Bergman, N.H.; Phillippy, A.M. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a Web browser. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerssen, A.; Bovee, T.H.F.; Klijnstra, M.D.; Poelman, M.; Portier, L.; Hoogenboom, R.L.A.P. First Report on the Occurrence of Tetrodotoxins in Bivalve Mollusks in The Netherlands. Toxins 2018, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrdjen, I.; Smith, Z.J.; Webster, A.M.; Nack, C.C.; Arndt, B.; Dormaeva, D.; Boyer, G.L.; Razavi, R.; Shaw, S.B. A novel artificial intelligence-powered cell counting tool coupled with digital microscopy for rapid field-assessment of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Limnol. Occeaography Methods 2025, 23, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, L.; Bachar, D.; Audic, S.; Bass, D.; Berney, C.; Bittner, L.; Boutte, C.; Burgaud, G.; de Vargas, C.; Decelle, J. The Protist Ribosomal Reference database (PR2): A catalog of unicellular eukaryote small sub-unit rRNA sequences with curated taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D597–D604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffer, S.; Lim, M.C.W.; Prost, S. NGSpeciesID: DNA barcode and amplicon consensus generation from long—Read sequencing data. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Turner, D.; Mesirov, J.P. igv.js: An embeddable JavaScript implementation of the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Bioinformatics 2022, 39, btac830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trainer, V.L.; Bates, S.S.; Lundholm, N.; Thessen, A.E.; Cochlan, W.P.; Adams, N.G.; Trick, C.G. Pseudo-nitzschia physiological ecology, phylogeny, toxicity, monitoring and impacts on ecosystem health. Harmful Algae 2012, 14, 271–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvey, A.; Claquin, P.; le Roy, B.; Jolly, O.; Fauchot, J. Physiological conditions favorable to domoic acid production by three Pseudo-nitzschia species. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2023, 559, 151851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, A.; Selander, E.; Peacock, M.; Kudela, R.M. Field monitoring of copepodamides using a new application for solid phase adsorption toxin tracking. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2024, 22, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, C.; Swan, S.C.; Turner, A.D.; Hatfield, R.G.; Mitchell, E.; Lafferty, S.; Morrell, N.; Rowland-Pilgrim, S.; Davidson, K. The presence of Pseudo-nitzschia australis in North Atlantic aquaculture sites, implications for monitoring Amnesic Shellfish Toxins. Toxins 2023, 15, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebour, M.V. The Dinoflagellates of Northern Seas; Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom: Plymouth, UK, 1925; p. 250. [Google Scholar]

- John, U.; Litaker, R.W.; Montresor, M.; Murray, S.; Brosnahan, M.L.; Anderson, D.M. Formal Revision of the Alexandrium tamarense Species Complex (Dinophyceae) Taxonomy: The Introduction of Five Species with Emphasis on Molecular-based (rDNA) Classification. Protist 2014, 165, 779–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, S.; Sampedro, N.; Larsen, J.; Moestrup, Ø.; Calado, A.J. Arguments against the proposal 2302 by John & al. to reject the name Gonyaulax catenella (Alexandrium catenella). Taxon 2015, 64, 634–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme van Reine, W.F. Report of the Nomenclature Committee for Algae: 15. Taxon 2017, 66, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.; Bresnan, E.; Graham, J.; Lacaze, J.-P.; Turrell, E.; Collins, C. Distribution diversity and toxin composition of the genus Alexandrium (Dinophyceae) in Scottish waters. Eur. J. Phycol. 2010, 45, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percy, L.A. An Investigation of the Phytoplankton of the Fal Estuary, UK and the Relationship Between Occurrence of Potentially Toxic Species and Associated Algal Toxins in Shellfish; University of Westminster: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, S.M.; Purdie, D.A.; Lilly, E.L.; Larsen, J.; Morris, S. Toxin Profile Pigment Composition and Large Subunit Rdna Phylogenetic Analysis of an Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) Strain Isolated fromthe Fleet Lagoon United Kingdom. J. Phycol. 2005, 41, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.M.; Dean, K.J.; Hartnell, D.M.; Percy, L.; Turner, A.D.; Lewis, J.M. The value of toxin profiles in the chemotaxonomic analysis of paralytic shellfish toxins in determining the relationship between British Alexandrium spp. and experimentally contaminated Mytilus sp. Harmful Algae 2022, 111, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wietkamp, S.; Krock, B.; Gu, H.; Voß, D.; Klemm, K.; Tillmann, U. Occurrence and distribution of Amphidomataceae (Dinophyceae) in Danish coastal waters of the North Sea, the Limfjord, and the Kattegat/Belt area. Harmful Algae 2019, 88, 101637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wietkamp, S.; Krock, B.; Clarke, D.; Voß, D.; Salas, R.; Kilcoyne, J. Distribution and abundance of azaspiracid-producing dinophyte species and their toxins in North Atlantic and North Sea waters in summer 2018. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, M.K.M.; Jeong, H.J.J.H.; Park, M.G.; Park, M.G. Revisiting the taxonomy of the “Dinophysis acuminata complex” (Dinophyta). Harmful Algae 2019, 88, 101657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, R.F.; Amorim, A.L.; Bresnan, E. Diversity and plastid types in Dinophysis acuminata complex (Dinophyceae) in Scottish waters. Harmful Algae 2014, 39, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolny, J.L.; Egerton, T.A.; Handy, S.M.; Stutts, W.L.; Smith, J.L.; Whereat, E.B.; Bachvaroff, T.R.; Henrichs, D.W.; Campbell, L.; Deeds, J.R. Characterization of Dinophysis spp. (Dinophyceae, Dinophysiales) from the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz Mendes, M.C.; de Castro Nunes, J.M.; Fraga, S.; Rodríguez, F.; Franco, J.M.; Riobó, P.; Branco, S.; Menezes, M. Morphology, molecular phylogeny and toxinology of Coolia and Prorocentrum strains isolated from the tropical South Western Atlantic Ocean. Bot. Mar. 2019, 62, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, S.M.; Purdie, D.A.; Morris, S. Morphology, toxin composition and pigment content of Prorocentrum lima strains isolated from a coastal lagoon in southern UK. Toxicon 2005, 45, 633–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillmann, U.; Gottschling, M.; Wietkamp, S.; Hoppenrath, M. Morphological and Phylogenetic Characterisation of Prorocentrum spinulentum, sp. nov. (Prorocentrales, Dinophyceae), a Small Spiny Species from the North Atlantic. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdennadher, M.; Zouari, A.B.; Medhioub, W.; Penna, A.; Hamza, A. Characterization of coolia spp. (gonyaucales, dinophyceae) from southern tunisia: First record of coolia malayensis in the mediterranean sea. Algae 2021, 36, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, M.; Dixon, P. Check-list of British marine algae—Third revision. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 1976, 56, 527–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, D. Provisional Atlas of the Marine Dinoflagellates of the British Isles; Biological Records Centre Institute of Terrestrial Ecology: Huntingdon, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, J.D.; Harland, R. The distribution of planktonic dinoflagellates and their cysts in the eastern and northeastern Atlantic Ocean. New Phytol. 1991, 118, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.J.; Lewis, R.J.; Jones, A.; Hoy, A.W.W. Cooliatoxin, the first toxin from Coolia monotis (dinophyceae). Nat. Toxins 1995, 3, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Smith, K.F.; Qiu, L.; Liu, C.; Yin, X.; Liu, Q. Development of Specific DNA Barcodes for the Dinophyceae Family Kareniaceae and Their Application in the South China Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Fan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, X.; Deng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Tang, Y.Z. Characterization of the Unarmored Dinoflagellate Karlodinium decipiens (Dinophyceae) from Jiaozhou Bay, China. Diversity 2024, 16, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Salas, M.F.; Laza-Martínez, A.; Hallegraeff, G.M. Novel unarmored dinoflagellates from the toxigenic family Kareniaceae (Gymnodiniales): Five new species of Karlodinium and one new Takayama from the Australian sector of the Southern Ocean. J. Phycol. 2008, 44, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.; Miller, P.I.; Wilding, T.A.; Shutler, J.; Bresnan, E.; Kennington, K.; Swan, S. A large and prolonged bloom of Karenia mikimotoi in Scottish Waters in 2006. Harmful Algae 2009, 8, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurekin, A.A.; Miller, P.I.; van der Woerd, H.J. Satellite discrimination of Karenia mikimotoi and Phaeocystis harmful algal blooms in European coastal waters: Merged classification of ocean colour data. Harmful Algae 2014, 31, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.K.; Tilstone, G.H.; Smyth, T.J.; Widdicombe, C.E.; Gloël, J.; Robinson, C.; Kaiser, J.; Suggett, D.J. Drivers and effects of Karenia mikimotoi blooms in the western English Channel. Prog. Oceanogr. 2015, 137, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoutte-Brunier, A.; Fernand, L.; Ménesguen, A.; Lyons, S.; Gohin, F.; Cugier, P. Modelling the Karenia mikimotoi bloom that occurred in the western English Channel during summer 2003. Ecol. Model. 2008, 210, 351–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.A.; Bolch, C.J.S.; Brett, S.; Chan, C.X.; Doubell, M.; Farrell, H.; Gaiani, G.; Greenhough, H.; Hallegraeff, G.; Harding, T.S.; et al. A catastrophic marine mortality event caused by a complex algal bloom including the novel brevetoxin producer, Karenia cristata (Dinophyceae). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobler, C.J.; Lonsdale, D.J.; Boyer, G.L. A review of the causes, effects, and potential management of harmful brown tide blooms caused by Aureococcus anophagefferens (Hargraves et Sieburth). Estuaries 2005, 28, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassus, P.; Chomérat, N.; Hess, P.; Nézan, E. Toxic and Harmful Microalgae of the World Ocean. In Micro-Algues Toxiques et Nuisibles de l’océan Mondial; IOC Manuals and Guides; International Society for the Study of Harmful Algae: Copenhagen, Denmark; Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; p. 68, (In Bilingual English/French). [Google Scholar]

- Boney, A.D. Observations on the silicoflagellate Dictyocha speculum Ehrenb. from the Firth of Clyde. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd 1973, 53, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G.; Lin, S. Genetic analysis of Noctiluca scintillans populations indicates low latitudinal differentiation in China but high China-America differences. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2016, 477, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, L.; Smith, K.; Selwood, A.; Mcnabb, P.; Munday, R.; Suda, S.; Molenaar, S.; Hallegraeff, G. Dinoflagellate Vulcanodinium rugosum identified as the causative organism of pinnatoxins in Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Phycologia 2011, 50, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, M.; Desanglois, G.; Hogeveen, K.; Fessard, V.; Leprêtre, T.; Mondeguer, F.; Guitton, Y.; Hervé, F.; Séchet, V.; Grovel, O.; et al. Cytotoxicity, fractionation and dereplication of extracts of the dinoflagellate vulcanodinium rugosum, a producer of pinnatoxin G. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 3350–3371. [Google Scholar]

- Jauffrais, T.; Kilcoyne, J.; Herrenknecht, C.; Truquet, P.; Séchet, V.; Miles, C.O.; Hess, P. Dissolved azaspiracids are absorbed and metabolized by blue mussels (Mytilus edulis). Toxicon 2013, 65, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, S.C.; Turner, A.D.; Bresnan, E.; Whyte, C.; Paterson, R.F.; McNeill, S.; Mitchell, E.; Davidson, K. Dinophysis acuta in Scottish Coastal Waters and its influence on Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxin profiles. Toxins 2018, 10, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Kulis, D.M.; Fux, E.; Smith, J.L.; Hess, P.; Zhou, Q.; Anderson, D.M. The effects of growth phase and light intensity on toxin production by Dinophysis acuminata from the northeastern United States. Harmful Algae 2011, 10, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Teixeira Alves, M.; Trinanes, J.A.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Haverson, D.; Bradley, K.; Baker-Austin, C.; Huggett, J.F.; Stewart, G.; Ritchie, J.M.; et al. Sea temperature influences accumulation of tetrodotoxin in British bivalve shellfish. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 885, 163905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Hatfield, R.G.; Walker, D.I.; Hooper, C.; Alewijnse, S.; Baker-Austin, C.; Turner, A.D.; Ritchie, J.M. Investigating non-native ribbon worm Cephalothrix simula as a potential source of Tetrodotoxin in British bivalve shellfish. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margarlamov, T.Y.; Melnikova, D.I.; Chernyshev, A.V. Tetrodotoxin-producing bacteria: Detection, distribution and migration of the toxin in aquatic systems. Toxins 2017, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Doan, T.; Le, P.; Pha, B.; Ho, T.; Hua, P.; Tran, Y.; Nguyen, T. Isolation, identification and characterisation of tetrodotoxin producing Bacillus amyloliquefacients B1 originated from Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.D.; Fenwick, D.; Powell, A.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Ford, C.; Hatfield, R.G.; Santos, A.; Martinez-Urtaza, J.; Bean, T.P.; Baer-Austin, C.; et al. New invasive nemertean species (Cephalothrix simula) in England with high levels of tetrodotoxin and a microbiome linked to toxin metabolism. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.D.; Dhanji-Rapkova, M.; Dean, K.; Milligan, S.; Hamilton, M.; Thomas, J.; Poole, C.; Haycock Spelman-Marriott, J.; Watson, A.; Hughes, K.; et al. Fatal canine intoxications linked to the presence of saxitoxins in stranded marine organisms following winter storm activity. Toxins 2018, 10, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coastal Monitoring. Real Time Data on Tidal Flows Around the Southwest of England. 2025. Available online: https://southwest.coastalmonitoring.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- VisitMyHarbour. Hourly Tidal Streams, English Channel West (NP250). 2025. Available online: https://www.visitmyharbour.com/articles/3174/hourly-tidal-streams-english-channel-west-np250 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Alharbi, W.; Petrovskii, S. Effect of complex landscape geometry on the invasive species spread: Invasion with stepping stones. J. Theor. Biol. 2019, 464, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidbury, H.J.; Taylor, N.G.H.; Copp, G.H.; Garnacho, E.; Stebbing, P.D. Predicting and mapping the risk of introduction of marine non-indigenous species into Great Britain and Ireland. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 3277–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundholm, N.; Bernard, C.; Churro, C.; Escalera, L.; Hoppenrath, M.; Iwataki, M.; Larsen, J.; Mertens, K.; Murray, S.; Probert, I.; et al. (Eds.) IOC-UNESCO Taxonomic Reference List of Harmful Microalgae; IOC-UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/hab (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Barnett, D.W.; Garrison, E.K.; Quinlan, A.R.; Strömberg, M.P.; Marth, G.T. BamTools: A C++ API and toolkit for analyzing and managing BAM files. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 1691–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C. Generating consensus sequences from partial order multiple sequence alignment graphs. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Medaka. 2018. Available online: https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: An online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W242–W245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, A.; Morrell, N.; Turner, A.D.; Maskrey, B.H. Method performance verification for the combined detection and quantitation of the marine neurotoxins cyclic imines and brevetoxin shellfish metabolites in mussels (Mytilus edulis) and oysters (Crassostrea gigas) by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Chrom. B 2021, 1179, 122864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genus/Species | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulcanodinium sp. | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1800 | nd | 400 | nd |

| Alexandrium sp. | nd | nd | 150 ± 70 | 100 ± 0 | 125 ± 50 | 400 | nd | nd |

| Amphidinium cartarae | nd | nd | nd | nd | 100 | nd | nd | nd |

| Dinophysis sp. | nd | 100 | 100 ± 0 | 150 ± 70 | nd | 250 ± 212 | nd | nd |

| Dinophysis acuminata | nd | 100 | 133 ± 58 | 300 ± 245 | 750 ± 712 | 467 ± 305 | 100 | 200 |

| Gymnodinium sp. | nd | nd | nd | nd | 100 | nd | nd | nd |

| Heterocapsa minima/Azadinium/Amphidoma group | nd | nd | nd | nd | 21,000 | 48,600 | 7,201,000 | nd |

| Indet. dinoflagellate | nd | nd | nd | nd | 100 | nd | nd | nd |

| Karenia sp. | nd | nd | nd | 100 ± 0 | 200 | 400 | nd | nd |

| Prorocentrum cordatum/balticum * | nd | nd | nd | nd | 466 ± 306 | 400 | 600 | nd |

| Prorocentrum lima | nd | 300 | 100 | 100 ± 0 | nd | 1200 ± 1414 | 100 | nd |

| Prymnesiophytes | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | 100 | nd | nd |

| Pseudo-Nitzschia delicatissima group (≤4.9 µm) | nd | nd | nd | 4800 | 1133 ± 702 | 800 | nd | nd |

| Pseudo-nitzschia multistriata | nd | nd | nd | 1200 | 267 ± 115 | 600 | nd | nd |

| Pseudo-Nitzschia seriata group (≥5 µm) | nd | nd | nd | 1200 | 600 ± 673 | 2000 | 400 | nd |

| Genus | Classification | Sequence Number | Region Analysed | Taxonomic Name | % Ident | Accession | Harmful Effect/Toxin Hazard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexandrium | Dinoflagellata | 1 | SSU—LSU | Alexandrium tamarense | 99.70% | DQ785891.1 | Non-toxic species |

| LSU | Alexandrium tamarense | 99.82% | KX599342.1 | ||||

| Azadinium | Dinoflagellata | SSU | Azadinium caudatum var. margalefii | 99.60% | JQ247707.1 | Non-toxic species | |

| 2 | ITS1-ITS2 | Azadinium caudatum var. margalefii | 99.43% | JQ247705.1 | |||

| LSU | Azadinium caudatum | 99.34% | JQ247709.1 | ||||

| Coolia | Dinoflagellata | SSU—LSU | Coolia monotis | 99.08% | AJ415509.1 | Neurotoxic/Cooliatoxin | |

| 3 | ITS1-ITS2 | Coolia monotis | 98.94% | KJ781411.2 | |||

| SSU | Coolia monotis | 99.25% | AJ415509.1 | ||||

| Dictyochophyceae | Dictyocha | 4a | SSU | Dictyocha speculum | 99.83% | U14385.1 | Gill damage/not toxic |

| ITS1-LSU | Dictyocha speculum | 99.80% | AF289046.1 | ||||

| Aureococcus | 4b | SSU | Aureococcus anophagefferens | 99.50% | AF117776.1 | Blocks light penetration/not toxic | |

| LSU | Aureococcus anophagefferens | 98.34% | AF289042.1 | ||||

| Dinophysis | Dinoflagellata | 5 | SSU—LSU | Dinophysis acuminata | 99.77% | MK860896.1 | Diahretic/Okadaic acid, Dinophysistoxins and pectenotoxins |

| Karlodinium | Dinoflagellata | 6 | ITS1-ITS2 | Karlodinium decipiens | 97.48% | LC521287.1 | Non-toxic species |

| LSU | Karlodinium antarcticum | 100.00% | EF469234.1 | No data available | |||

| Karenia | Dinoflagellata | 7 | SSU—LSU | Karenia mikimotoi | 99.11% | KU314866.1 | Ichthyotoxic/Gymnocins and Bevatoxins |

| Noctiluca | Dinoflagellata | 8 | SSU—LSU | Noctiluca scintillans | 99.63% | OQ132786.1 | Oxygen depletion/not toxic |

| ITS1-ITS2 | Noctiluca scintillans | 99.36% | KR607082.1 | ||||

| Prorocentrum | Dinoflagellata | SSU | Prorocentrum lima | 99.82% | MK541784.1 | Diahretic/Okadaic acid and Dinophysis toxin-1 | |

| 10a | ITS1-ITS2 | Prorocentrum lima | 99.68% | AB189765.1 | |||

| LSU | Prorocentrum lima | 99.85% | MW177927.1 | ||||

| SSU | Prorocentrum spinulentum | 100.00% | OQ220501.1 | No data | |||

| 10b | ITS1-ITS2 | Prorocentrum spinulentum | 100.00% | OQ220500.1 | |||

| LSU | Prorocentrum spinulentum | 99.85% | OP231463.1 | ||||

| Pseudo-nitzschia | 11a | ITS2 | Pseudo-nitzschia plurisecta | 100.00% | MK729547.1 | Amnesic/Domoic acid | |

| Stramenopiles | 11b | ITS2 | Pseudo-nitzschia delicatissima | 100.00% | KM245508.1 | ||

| Ochrophytina | 11c | ITS2 | Pseudo-nitzschia fraudulenta | 100.00% | MK106639.1 | ||

| 11d | ITS2 | Pseudo-nitzschia australis | 100.00% | JN599166.1 |

| Date Collected | Sample Number | Species | Island | Location | DA | PST | TTX | OA/DTXs | AZAs | CIs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 March 2020 | 20 | Co | St. Mary’s | Old Town Bay | nd | 3.5 | nd | nd | 1.1 | nd |

| 9 March 2020 | 21a | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 4.6 | 2.6 | 0.2 |

| 9 March 2020 | 21b | SC | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 10 March 2020 | 33 | Co | Tresco | Tresco/Bryher | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.2 | 0.4 |

| 10 March 2020 | 49 | Co | Tresco | Raven’s Porth | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| 10 March 2020 | 50 | SC | Tresco | Raven’s Porth | nd | 3.2 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| 11 March 2020 | 47 | SC | Tresco | English Island Point | nd | nd | nd | nd | 1 | nd |

| 11 March 2020 | 48 | Rz | St. Martin’s | St. Martin’s Flats | nd | nd | nd | 4.6 | nd | nd |

| 11 March 2020 | 51 | Co | St. Martin’s | St. Martin’s Flats | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.2 | nd |

| 13 March 2020 | 45 | Co | Bryher | Hangman’s Point | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.2 | 0.1 |

| 13 March 2020 | 46 | Co | Bryher | Green Bay Quay | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.4 | 0.4 |

| 1 April 2020 | 52 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.2 | nd |

| 12 April 2020 | 55 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 3.9 | 6.5 | nd |

| 30 April 2020 | 56 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 2.6 | 3.4 | 2 |

| 30 April 2020 | 61 | CC | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 12 | 1.7 | nd |

| 15 May 2020 | 62 | CC | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | nd | nd | nd | 28 | 8.4 | nd |

| 24 May 2020 | 59 | M | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | 1.18 | nd | nd | 7.4 | 6.2 | nd |

| 3 June 2020 | 63 | CC | St. Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | 9.6 | 4.2 | nd |

| 10 June 2020 | 64 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | 4.1 | 6.88 | 16.0 | 5.1 | nd |

| 15 June 2020 | 65 | Co | St. Mary’s | Bar Point | nd | nd | 25.2 | 21.2 | 2.3 | nd |

| 21 June 2020 | 53 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 16.88 | 11.8 | 3.6 | nd |

| 28 June 2020 | 54 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 3.77 | 10.6 | 2 | 2.9 |

| 4 July 2020 | 66 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porthmellon | nd | 3.6 | 6.52 | 34.2 | nd | nd |

| 10 July 2020 | 67 | CC | St. Mary’s | Little Porth | nd | nd | nd | 42.3 | 4.2 | nd |

| 18 July 2020 | 68 | CC | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 2.45 | 16.9 | 6.3 | nd |

| 28 July 2020 | 69 | Co | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | nd | nd | nd | 24.3 | 12.3 | nd |

| 9 August 2020 | 57 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 0.53 | 75 | 2.8 | nd |

| 9 August 2020 | 58 | M | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | 1.29 | nd | nd | 4.9 | nd | nd |

| 20 August 2020 | 70 | Co | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | nd | nd | 1.13 | 24.3 | 11.7 | nd |

| 1 September 2020 | 71 | Co | St. Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 2.13 | 12.3 | 4.5 | nd |

| 7 September 2020 | 72 | Co | St. Mary’s | Deep Point | nd | nd | nd | 8.2 | 3.2 | nd |

| 29 November 2020 | 128 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | 0.57 | nd | nd | 14.6 | 9 | nd |

| 29 November 2020 | 129 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | nd | 8.4 | nd |

| 20 December 2020 | 130 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | 0.42 | nd | nd | 10.3 | 9 | nd |

| 20 December 2020 | 131 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | 0.37 | nd | nd | nd | 7.8 | nd |

| 3 January 2021 | 132 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | 0.62 | nd | nd | 10.1 | 8.2 | nd |

| 3 January 2021 | 133 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | nd | 9.9 | nd |

| 17 January 2021 | 134 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 7.8 | 8.6 | nd |

| 17 January 2021 | 135 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | 0.34 | nd | nd | nd | 4.1 | nd |

| 31 January 2021 | 136 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 13.2 | 3.6 | nd |

| 31 January 2021 | 137 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | nd | 4.3 | nd |

| 8 February 2021 | 138 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | 0.35 | nd | nd | nd | 4 | nd |

| 28 February 2021 | 139 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | 15.1 | 9.5 | nd |

| 28 February 2021 | 140 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | 8.8 | nd |

| 2 March 2021 | 141 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | 11 | 10.6 | nd |

| 13 March 2021 | 142 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | 9.3 | nd |

| 4 April 2021 | 143 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | 12.2 | 8.6 | 2.4 |

| 13 April 2021 | 144 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | 0.56 | nd | nd | 7.3 | 8.8 | nd |

| 25 April 2021 | 145 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | 0.32 | nd | nd | nd | 9.2 | nd |

| 7 May 2021 | 146 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.8 | nd |

| 16 May 2021 | 147 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | nd | 3.8 | nd |

| 1 June 2021 | 148 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | 3.77 | 12.5 | 8.6 | nd |

| 10 June 2021 | 149 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 8.46 | 30.1 | 8.6 | nd |

| 21 June 2021 | 150 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | 12.3 | 14.3 | 4.3 | nd |

| 29 June 2021 | 151 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | 2.46 | 8.6 | 8.3 | nd |

| 8 July 2021 | 152 | Co | St Mary’s | Porth Hellick | nd | nd | nd | 4.3 | 8.5 | nd |

| 14 July 2021 | 153 | Co | St Mary’s | Old Town | nd | nd | nd | nd | 2.1 | nd |

| Sample | Species | DA | PST | OA/DTXs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lab | LFA | Lab | LFA | Lab | LFA | ||

| 20 | Co | nd | Low | 3.5 | Low | nd | Low |

| 50 | SC | nd | Low | 3.2 | Low | nd | Low |

| 48 | Rz | nd | Low | nd | Low | 4.6 | Low |

| 61 | CC | nd | Low | nd | Low | 12 | Low |

| 62 | CC | nd | Low | nd | Low | 28 | Low |

| 64 | Co | nd | Low | 4.1 | Low | 16.0 | Low |

| 65 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 21.2 | Low |

| 66 | Co | nd | Low | 3.6 | Low | 34.2 | Medium |

| 67 | CC | nd | Low | nd | Low | 42.3 | Medium |

| 68 | CC | nd | Low | nd | Low | 16.9 | Low |

| 69 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 24.3 | Low |

| 57 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 75 | Medium |

| 58 | M | 1.29 | Low | nd | Low | 4.9 | Low |

| 70 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 24.3 | Low |

| 132 | Co | 0.62 | Low | nd | Low | 10.1 | Low |

| 139 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 15.1 | Low |

| 141 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 11 | Low |

| 143 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 12.2 | Low |

| 149 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 30.1 | Low |

| 150 | Co | nd | Low | nd | Low | 14.3 | Low |

| Analyte | LOD | Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DA | 0.2 mg/kg | LC-UV | [59] |

| LTs (OA, DTXs, AZAs) | 0.5 µg/kg | UPLC-MS/MS | [63,64] |

| YTXs | 4.2 µg/kg | UPLC-MS/MS | [64] |

| Cyclic imines | 0.1 µg/kg | UPLC-MS/MS | [157] |

| STX, GTX5, C1&2, GTX6 | 0.5 µg STX di-HCl eq/kg | HILIC-MS/MS | [69] |

| dcNEO, dcSTX | 1.0 µg STX di-HCl eq/kg | HILIC-MS/MS | [69] |

| dcGTX2&3, C3&4 | 2.4 µg STX di-HCl eq/kg | HILIC-MS/MS | [69] |

| GTX1-4 | 2.7 µg STX di-HCl eq/kg | HILIC-MS/MS | [69] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turner, A.D.; Dean, K.J.; Lewis, A.M.; Hartnell, D.M.; Jenkins, Z.; Bear, B.; Mace, A.; Almeida, N.; van Ree, R.; Etchells, K.; et al. ScillyHAB: A Multi-Disciplinary Survey of Harmful Marine Phytoplankton and Shellfish Toxins in the Isles of Scilly: Combining Citizen Science with State-of-the-Art Monitoring in an Isolated UK Island Territory. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120478

Turner AD, Dean KJ, Lewis AM, Hartnell DM, Jenkins Z, Bear B, Mace A, Almeida N, van Ree R, Etchells K, et al. ScillyHAB: A Multi-Disciplinary Survey of Harmful Marine Phytoplankton and Shellfish Toxins in the Isles of Scilly: Combining Citizen Science with State-of-the-Art Monitoring in an Isolated UK Island Territory. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):478. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120478

Chicago/Turabian StyleTurner, Andrew D., Karl J. Dean, Adam M. Lewis, David M. Hartnell, Zoe Jenkins, Beth Bear, Amy Mace, Nevena Almeida, Rob van Ree, Kerra Etchells, and et al. 2025. "ScillyHAB: A Multi-Disciplinary Survey of Harmful Marine Phytoplankton and Shellfish Toxins in the Isles of Scilly: Combining Citizen Science with State-of-the-Art Monitoring in an Isolated UK Island Territory" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120478

APA StyleTurner, A. D., Dean, K. J., Lewis, A. M., Hartnell, D. M., Jenkins, Z., Bear, B., Mace, A., Almeida, N., van Ree, R., Etchells, K., Tibbs, I., Jesenko, P., Lewin, L., Robey, N., Banfield, N., Page, S., Belsham, G., Maskrey, B. H., & Hatfield, R. G. (2025). ScillyHAB: A Multi-Disciplinary Survey of Harmful Marine Phytoplankton and Shellfish Toxins in the Isles of Scilly: Combining Citizen Science with State-of-the-Art Monitoring in an Isolated UK Island Territory. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 478. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120478