Synergistic Protective Effects of Haematococcus pluvialis-Derived Astaxanthin and Walnut Shell Polyphenols Against Particulate Matter (PM)2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Optimization of Extract Ratio

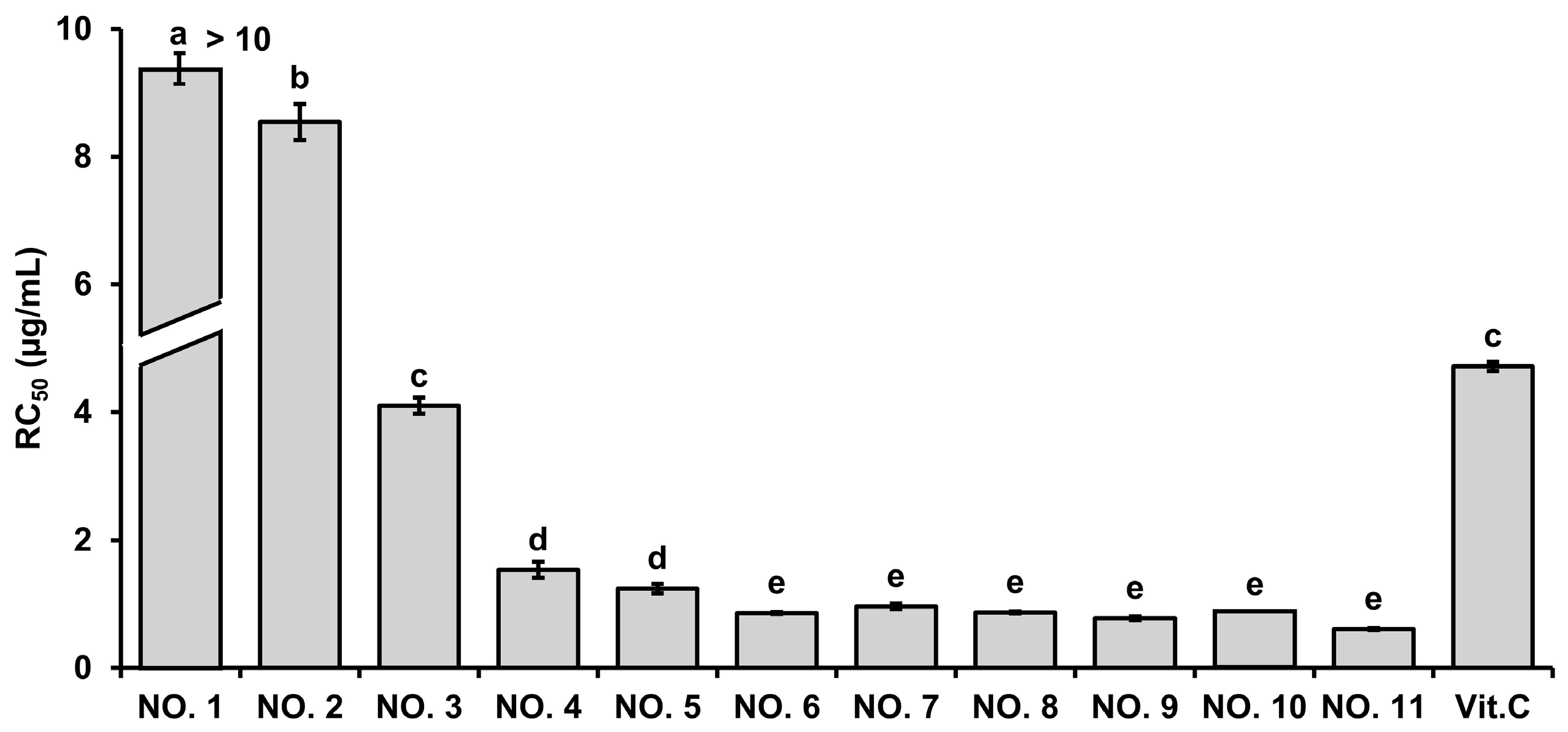

2.1.1. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

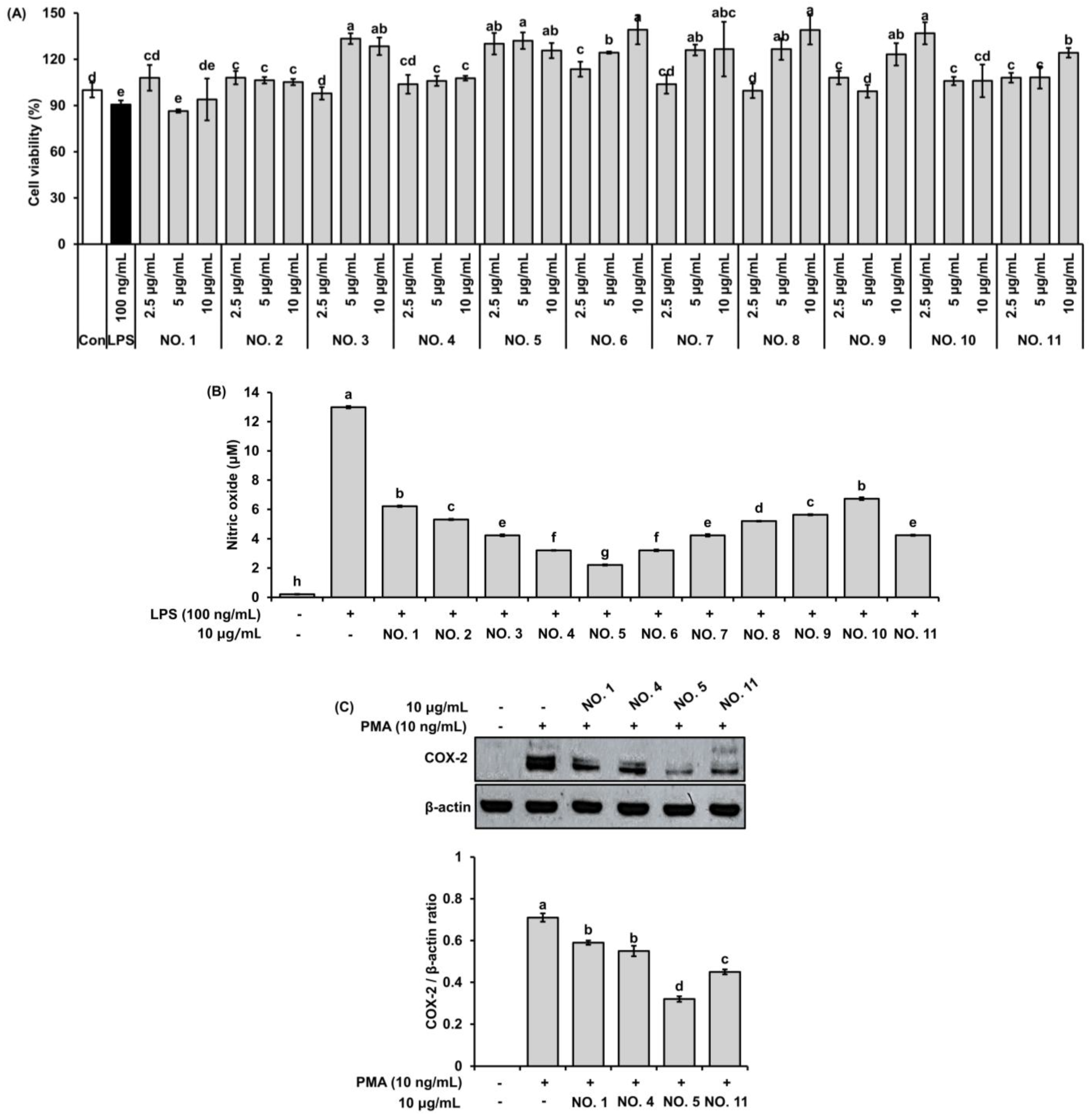

2.1.2. Cytotoxicity

2.1.3. Inhibitory Effect on NO Production

2.1.4. Suppression of COX-2 Protein Expression in Pulmonary Epithelial Cells

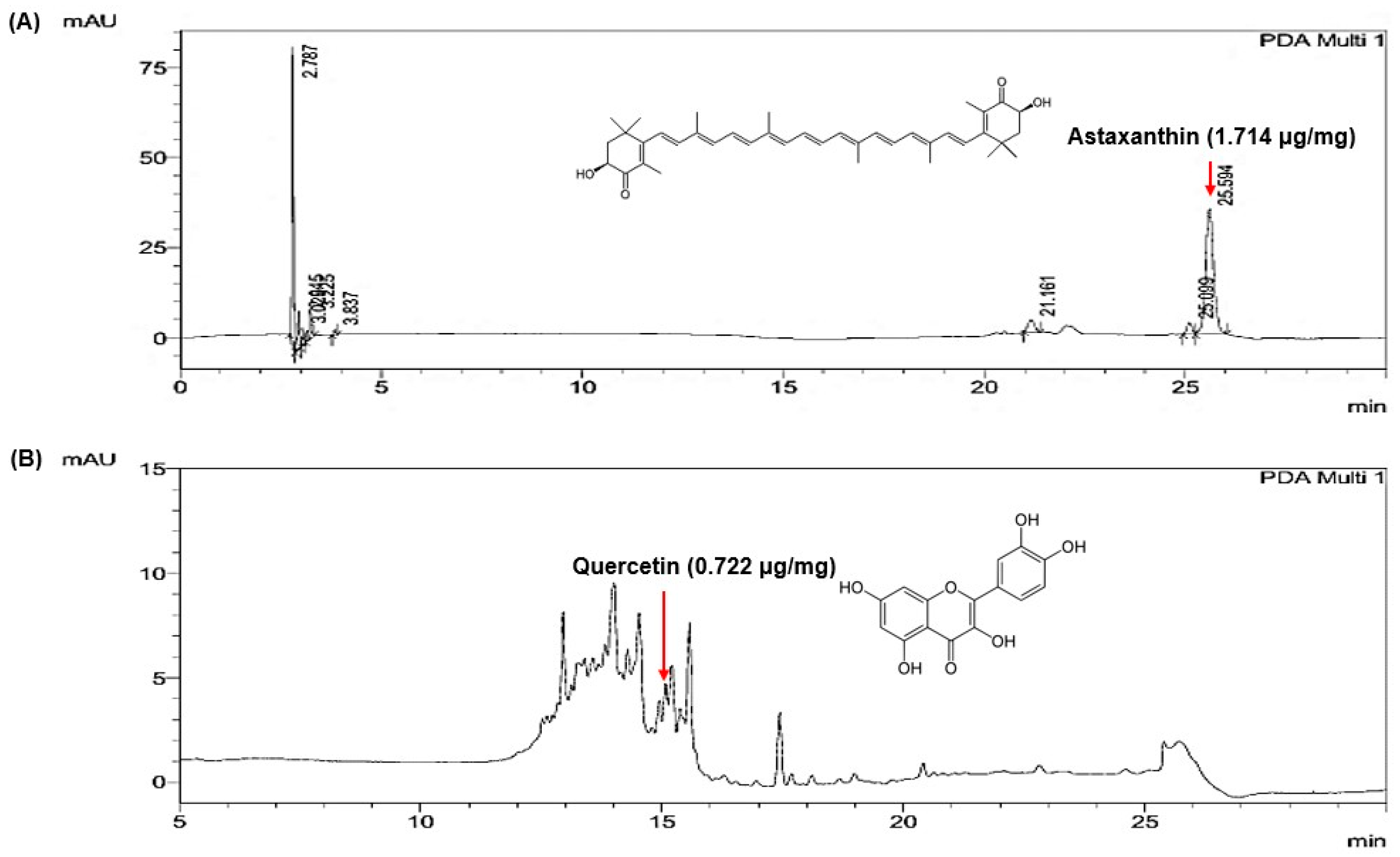

2.2. Quantification of Marker Compounds in the Selected Extract Mixture

2.3. Molecular Docking Analysis of Quercetin and Astaxanthin with COX-2

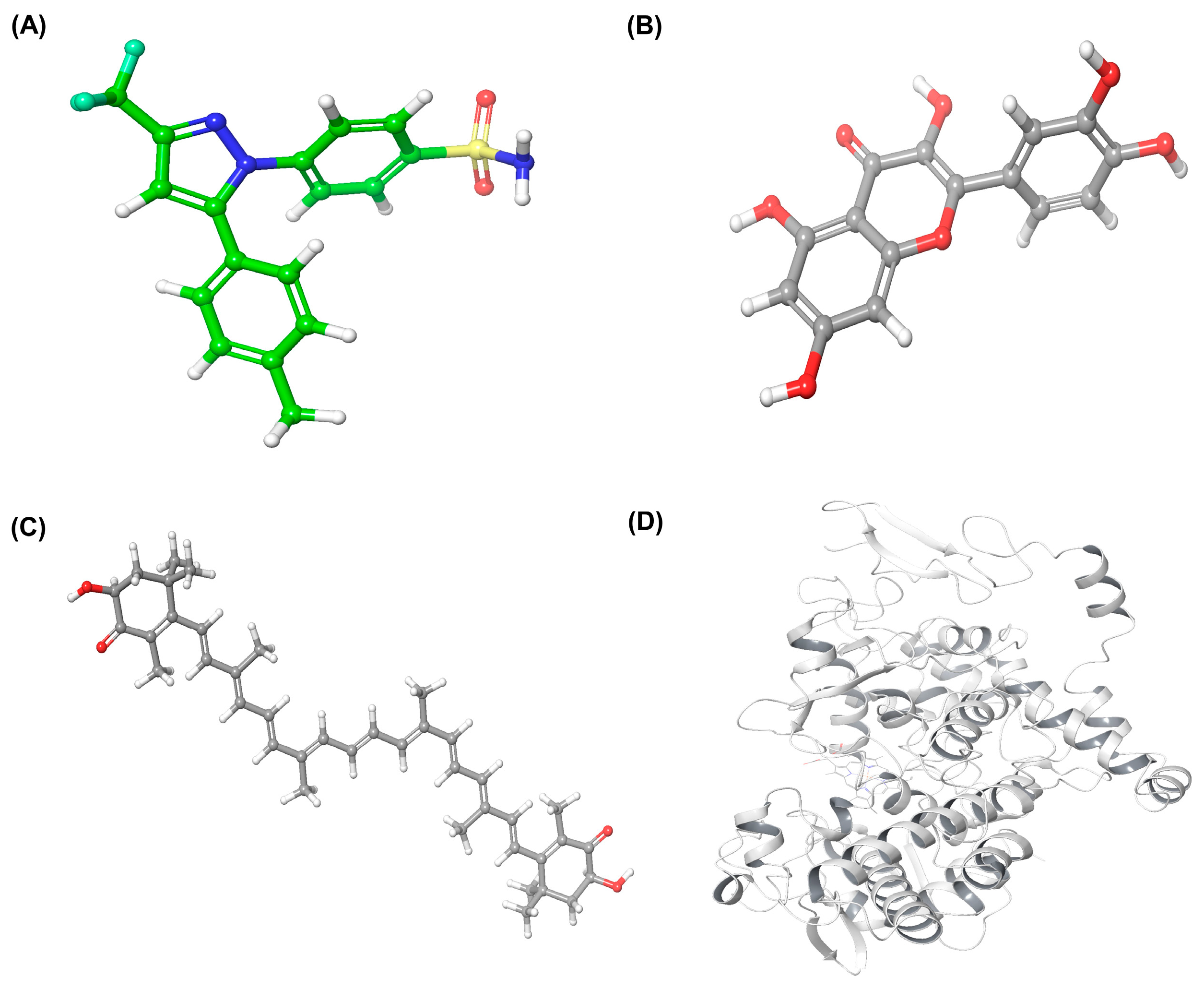

2.3.1. Ligand and Protein Preparation

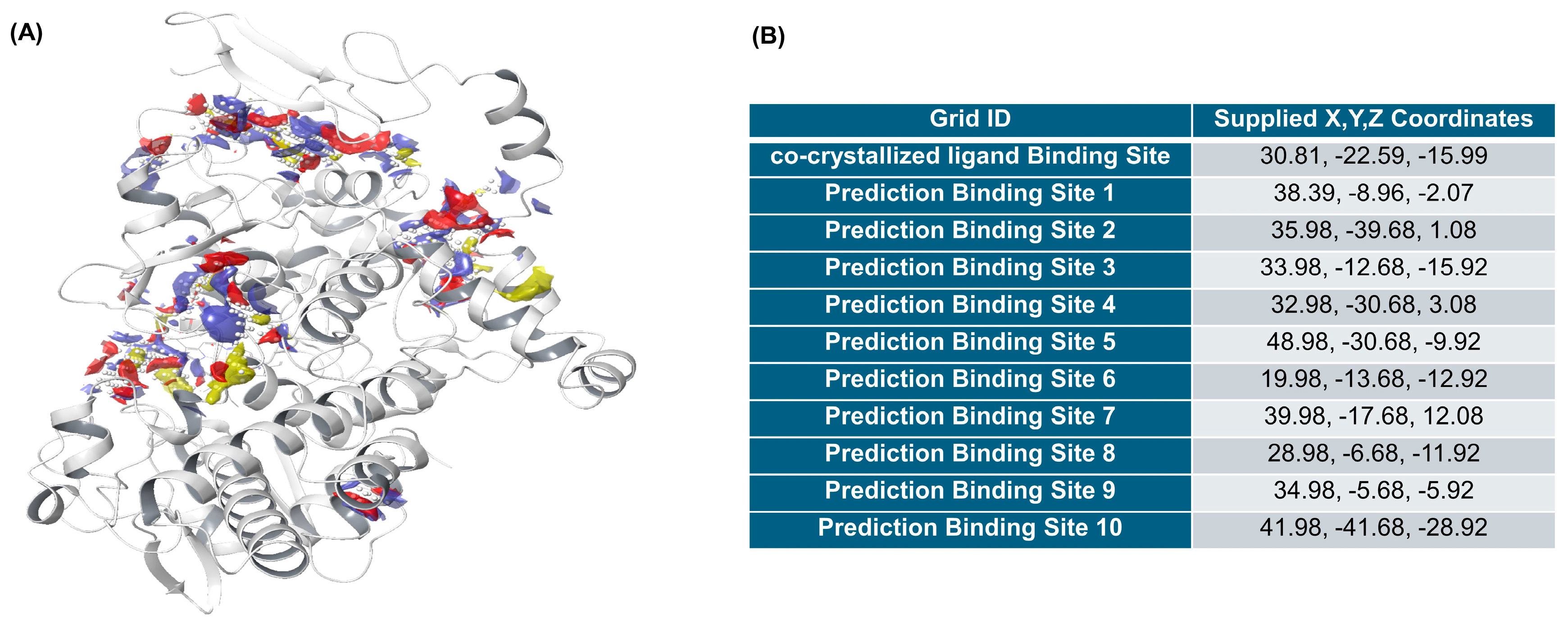

2.3.2. Identification of Binding Sites

2.3.3. Docking Validation

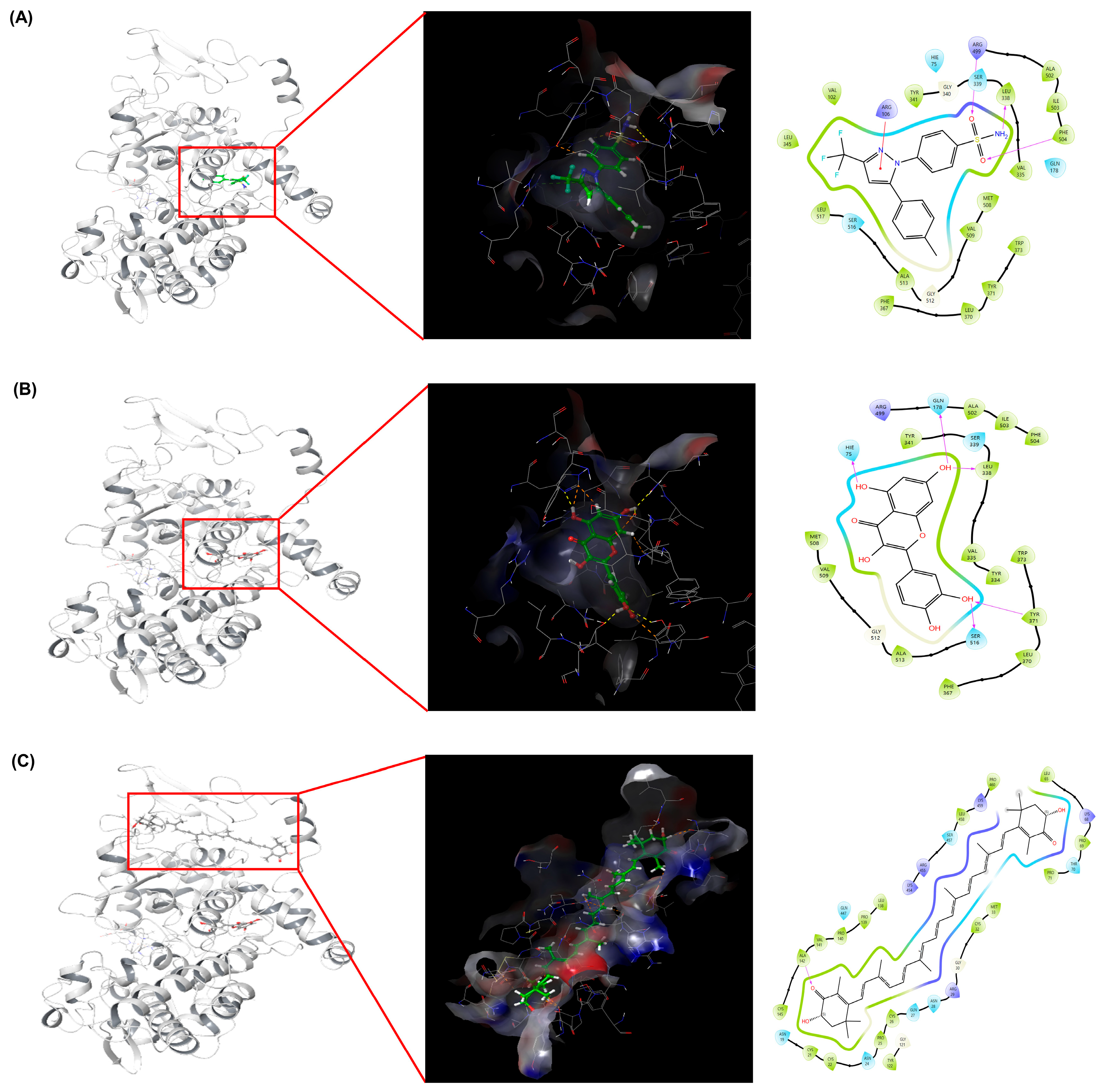

2.3.4. Molecular Docking and Interaction Analysis

2.4. Protective Effects of HW Extracts Against PM2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation in Mice

2.4.1. BALF Cell Analysis

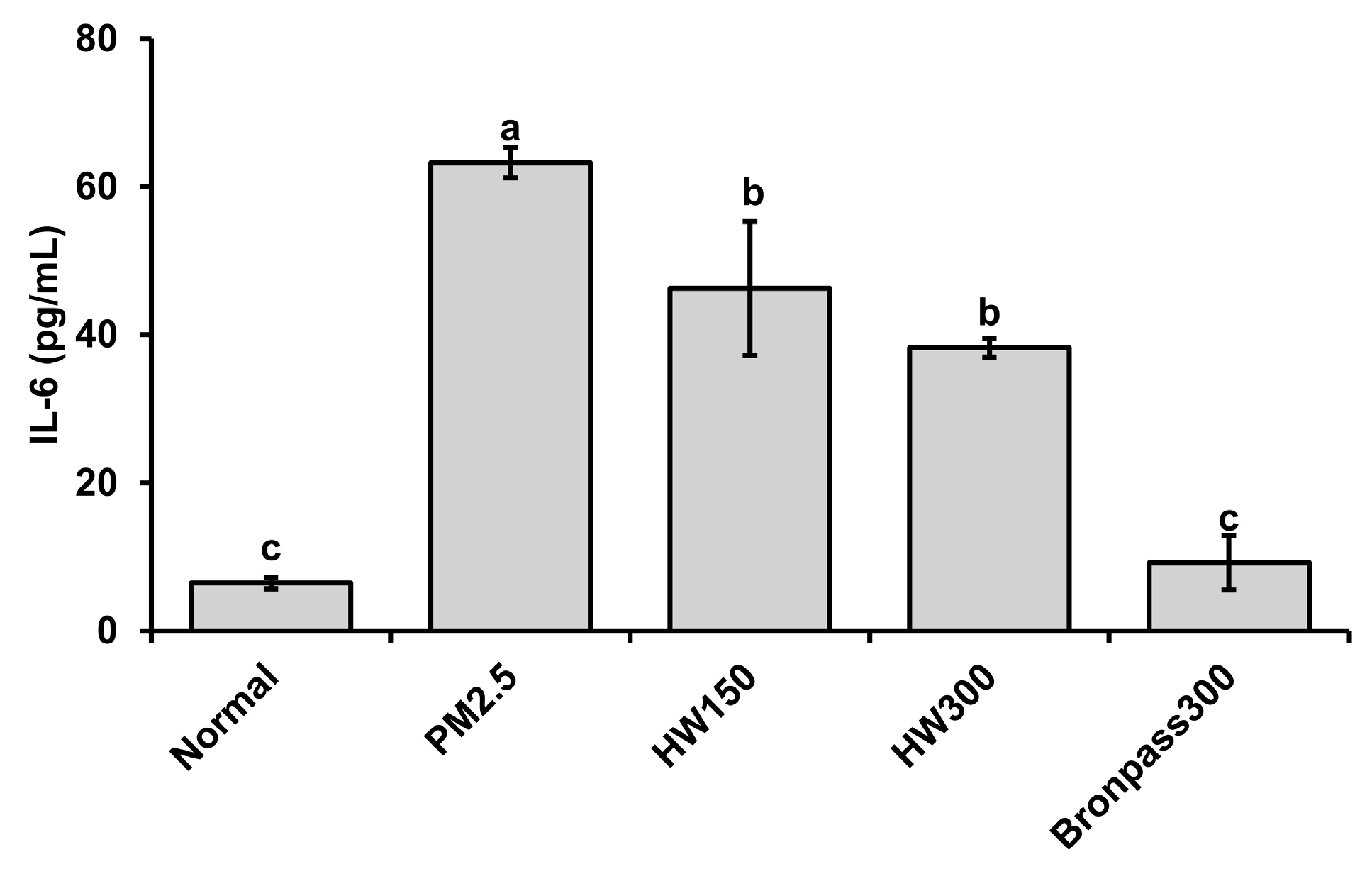

2.4.2. Serum IL-6 Analysis

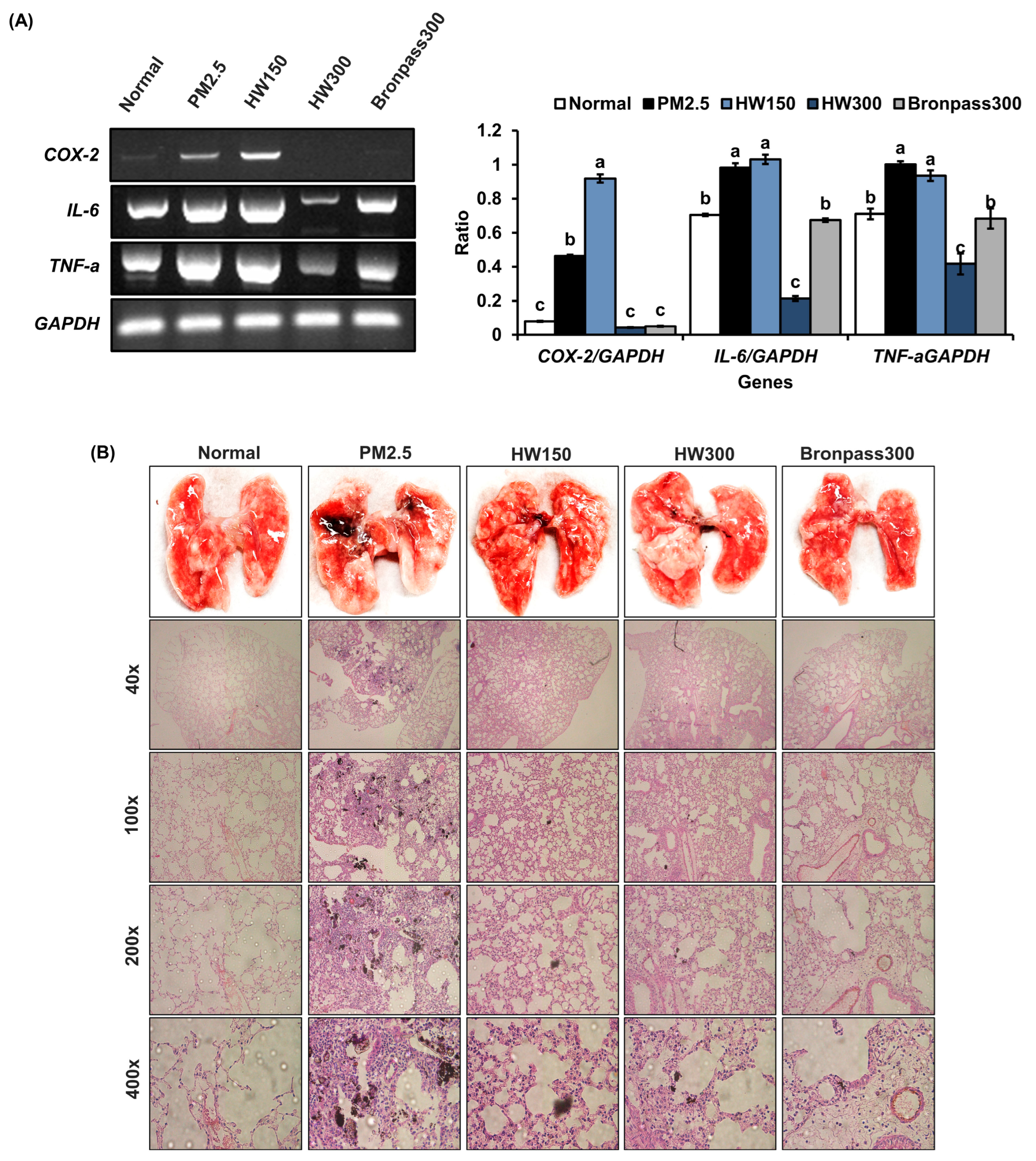

2.4.3. Pulmonary Tissue Analysis (RT-PCR and Histopathology)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Preparation of Extracts and Mixture Formulations

4.3. 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) Radical Scavenging Assay

4.4. Cell Culture

4.5. Cell Viability (MTT) Assay

4.6. Nitric Oxide (NO) Production Assay

4.7. Western Blot Analysis

4.8. HPLC Analysis of Marker Compounds

4.9. Determination of Total Polyphenol and Total Flavonoid Contents

4.10. Molecular Modeling and Docking Simulation

4.10.1. Ligand Preparation

4.10.2. Protein Preparation

4.10.3. Grid Generation

4.10.4. Ligand Docking

4.10.5. Ligand–Protein Interaction Analysis

4.11. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects in a PM2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation Mouse Model

4.11.1. PM2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation Model and Experimental Design

4.11.2. Total White Blood Cell Count in BALF

4.11.3. Measurement of Serum IL-6 Levels

4.11.4. Histopathological Examination of Pulmonary Tissue (H&E Staining)

4.11.5. Analysis of Inflammatory Gene Expression in Pulmonary Tissue (RT-PCR)

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-kappa B |

| AP-1 | Linear dichroism |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| PMA | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| BALF | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

References

- Zhai, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Xin, L. PM2.5 induces inflammatory responses via oxidative stress-mediated mitophagy in Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Toxicol. Res. 2022, 11, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K. Air-Pollutant Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5)-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Diseases: Possible Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 2148–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Vargas, M.P.; Montero-Vargas, J.M.; Debray-García, Y.; Vizuet-de-Rueda, J.C.; Loaeza-Román, A.; Terán, L.M. Oxidative Stress and Air Pollution: Its Impact on Chronic Respiratory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, L.; Qi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, L. Effects of Different Components of PM2.5 on the Expression Levels of NF-κB Family Gene mRNA and Inflammatory Molecules in Human Macrophage. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.S.; Kang, K.A.; Piao, M.J.; Ahn, M.J.; Yi, J.M.; Hyun, Y.M.; Kim, S.H.; Ko, M.K.; Park, C.O.; Hyun, J.W. Particulate Matter Induces Inflammatory Cytokine Production via Activation of NFκB by TLR5–NOX4–ROS Signaling in Human Skin Keratinocyte and Mouse Skin. Redox Biol. 2019, 21, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, D.; Jin, M.; Bai, C.; Song, Y. Urban Particulate Matter Triggers Lung Inflammation via the ROS–MAPK–NF-κB Signaling Pathway. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 4398–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Hu, J.; Ye, D.; Bai, G.; Liu, S.; Hong, W.; Guo, M.; Ran, P. PM2.5 Induces Airway Remodeling in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases via the Wnt5a/β-Catenin Pathway. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2021, 16, 3285–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayalar, Ö.; Rajabi, H.; Konyalilar, N.; Mortazavi, D.; Tuşe Aksoy, G.; Wang, J.; Bayram, H. Impact of Particulate Air Pollution on Airway Injury and Epithelial Plasticity: Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1324552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-M.; Huang, T.-H.; Chi, M.-C.; Guo, S.-E.; Lee, C.-W.; Hwang, S.-L.; Shi, C.-S. N-acetylcysteine alleviates fine particulate matter (PM2.5)-induced lung injury by attenuation of ROS-mediated recruitment of neutrophils and Ly6Chigh monocytes and lung inflammation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA Approves BRINSUPRI™ (Brensocatib) as the First and Only Treatment for Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis, a Serious, Chronic Lung Disease. BioSpace, Press Release. 12 August 2025. Available online: https://investor.insmed.com/2025-08-12-FDA-Approves-BRINSUPRI-TM-brensocatib-as-the-First-and-Only-Treatment-for-Non-Cystic-Fibrosis-Bronchiectasis,-a-Serious,-Chronic-Lung-Disease (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Wang, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Zhang, L. Does Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use Modify All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality Associated with PM2.5 and Its Components? A Nationally Representative Cohort Study (2007–2017). Environ. Health 2024, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péter, S.; Holguin, F.; Wood, L.G.; Clougherty, J.E.; Raederstorff, D.; Antal, M.; Weber, P.; Eggersdorfer, M. Nutritional Solutions to Reduce Risks of Negative Health Impacts of Air Pollution. Nutrients 2015, 7, 10398–10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuraisingam, S.L.; Heijink, I.; Goh, B.-H.; Yow, Y.-Y. Green Remedies: Pharmacological Potential of Phytonutrients for Combatting Air Pollution-Related Respiratory Diseases. Med. Drug Discov. 2026, 29, 100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Domínguez, M.C.; Espinosa, C.; Paredes, A.; Palma, J.; Jaime, C.; Vílchez, C.; Cerezal, P. Determining the Potential of Haematococcus pluvialis Oleoresin as a Rich Source of Antioxidants. Molecules 2019, 24, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, T.; Ito, H.; Yoshida, T. Antioxidative Polyphenols from Walnuts (Juglans regia L.). Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manterola-Barroso, C.; Godoy Sanchez, K.; Scheuermann, E.; Padilla-Contreras, D.; Morina, F.; Meriño-Gergichevich, C. Antioxidant and Physico-Structural Insights of Walnut (Juglans regia) and Hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) Shells: Implications for Southern Chile By-Product Valorization. Resources 2025, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera-Ciapara, I.; Félix-Valenzuela, L.; Goycoolea, F.M. Astaxanthin: A Review of Its Chemistry and Applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mularczyk, M.; Michalak, I.; Marycz, K. Astaxanthin and Other Nutrients from Haematococcus pluvialis—Multifunctional Applications. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Sakamoto, Y. Singlet Oxygen Quenching Ability of Astaxanthin Esters from the Green Alga Haematococcus pluvialis. Biotechnol. Lett. 1999, 21, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Saso, L.; D’Angeli, F.; Calabrese, V.; Intrieri, M.; Scapagnini, G. Astaxanthin as a Modulator of Nrf2, NF-κB, and Their Crosstalk: Molecular Mechanisms and Possible Clinical Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Luo, J.; Jing, X.; Guo, J.; Yao, X.; Hao, X.; Ye, Y.; Liang, S.; Lin, J.; Wang, G.; et al. Astaxanthin Protects against Osteoarthritis via Nrf2: A Guardian of Cartilage Homeostasis. Aging 2019, 11, 10513–10531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, S.; Wang, F.; Li, C. Protective Effects of Astaxanthin against Oxidative Stress: Attenuation of TNF-α-Induced Oxidative Damage in SW480 Cells and Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis-Associated Cancer in C57BL/6 Mice. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Hua, S.; Deng, J.; Du, Z.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Z.; Khan, N.U.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Z. Astaxanthin Activated the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway to Enhance Autophagy and Inhibit Ferroptosis, Ameliorating Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 42887–42903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, K.; Agarwal, N.; Rodriguez-Palacios, A.; Basson, A.R. Regulation of Intestinal Inflammation by Walnut-Derived Bioactive Compounds. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourais, I.; Elmarrkechy, S.; Taha, D.; Badaoui, B.; Mourabit, Y.; Salhi, N.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Al Awadh, A.A.; Bouyahya, A.; Goh, K.W.; et al. Comparative Investigation of Chemical Constituents of Kernels, Leaves, Husk, and Bark of Juglans regia L., Using HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS Analysis and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant, Antidiabetic, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 8989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Jamieson, S.; Pandey, A.K.; Bishayee, A. Neuroprotective Potential of Ellagic Acid: A Critical Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1211–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizeșan, I.; Rusu, M.E.; Georgiu, C.; Pop, A.; Ștefan, M.-G.; Muntean, D.-M.; Mirel, S.; Vostinaru, O.; Kiss, B.; Popa, D.-S. Antitussive, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of a Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Septum Extract Rich in Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megantara, S.; Yodha, M.W.A.; Sahidin, I.; Diantini, A.; Levita, J. Pharmacophore Screening and Molecular Docking of Phytoconstituents in Polygonum sagittatum for Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors Discovery. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, F.; Yuan, Y. Inhibitory Effects of Quercetin on the Progression of Liver Fibrosis through the Regulation of NF-κB/IκBα, p38 MAPK, and Bcl-2/Bax Signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 47, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado-Serrano, A.B.; Martín, M.Á.; Bravo, L.; Goya, L.; Ramos, S. Quercetin Attenuates TNF-Induced Inflammation in Hepatic Cells by Inhibiting the NF-κB Pathway. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Eltayeb, W.A.; Rakshit, G.; El-Arabey, A.A.; Khan, J.; Aldosari, S.M.; Alshehri, B.; Abdalla, M. Dual Synergistic Inhibition of COX and LOX by Potential Chemicals from Indian Daily Spices Investigated through Detailed Computational Studies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.P.; Manju, S.L.; Ethiraj, K.R.; Elias, G. Safer Anti-Inflammatory Therapy through Dual COX-2/5-LOX Inhibitors: A Structure-Based Approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 121, 356–381. [Google Scholar]

- Rouzer, C.A.; Marnett, L.J. Structural and Chemical Biology of the Interaction of Cyclooxygenase with Substrates and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7592–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrera, N.; Bitto, A. Evidence for Using a Dual COX-1/2 and 5-LOX Inhibitor in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 1077–1078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ranjbar, M.M.; Assadolahi, V.; Yazdani, M.; Nikaein, D.; Rashidieh, B. Virtual Dual Inhibition of COX-2/5-LOX Enzymes Based on Binding Properties of Alpha-Amyrins, the Anti-Inflammatory Compound as a Promising Anti-Cancer Drug. EXCLI J. 2016, 15, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Idris, M.H.M.; Amin, S.N.M.; Amin, S.N.H.M.; Nyokat, N.; Khong, H.Y.; Selvaraj, M.; Zakaria, Z.A.; Shaameri, Z.; Hamzah, A.S.; Teh, L.K.; et al. Flavonoids as Dual Inhibitors of Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX): Molecular Docking and In Vitro Studies. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2022, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazai, E.; Bikadi, Z.; Zsila, F.; Lockwood, S.F. Non-Covalent Binding of Disodium Disuccinate Astaxanthin to the Catalytic Site of Phosphodiesterase 5A: A Molecular Modeling Study. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2007, 4, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Miligy, M.M.M.; Al-Kubeisi, A.K.; Bekhit, M.G.; El-Zemity, S.R.; Nassra, R.A.; Hazzaa, A.A. Towards Safer Anti-Inflammatory Therapy: Synthesis of New Thymol-Pyrazole Hybrids as Dual COX-2/5-LOX Inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y. Quercetin Alleviates PM2.5-Induced Chronic Lung Injury in Mice by Targeting Ferroptosis. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.X.; Xiong, F. Astaxanthin and Its Effects in Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Molecules 2020, 25, 5342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, I.K.; Möller, S.; Elle, C.; Hindersin, S.; Kramer, A.; Labes, A. Optimization of Astaxanthin Recovery in the Downstream Process of Haematococcus pluvialis. Foods 2022, 11, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.-E.; Shin, C.Y.; Han, S.-H.; Kwon, K.J. Astaxanthin Suppresses PM2.5-Induced Neuroinflammation by Regulating Akt Phosphorylation in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-J.; Bai, S.-K.; Lee, K.-S.; Namkoong, S.; Na, H.-J.; Ha, K.-S.; Han, J.-A.; Yim, S.-V.; Chang, K.; Kwon, Y.-G.; et al. Astaxanthin Inhibits Nitric Oxide Production and Inflammatory Gene Expression by Suppressing IκB Kinase-Dependent NF-κB Activation. Mol. Cells 2003, 16, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, H.-Y.; Ma, D.-L.; Leung, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-C.; Hour, T.-C.; Wang, H.-M.D. Purified Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis Promotes Tissue Regeneration by Reducing Oxidative Stress and the Secretion of Collagen In Vitro and In Vivo. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 4946902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, T.-Y.; Sim, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y.; Ryu, S.; Baek, J.-S.; Kim, D.G.; Sim, J.; An, H.-J. Hot-Melt Extrusion Drug Delivery System–Formulated Haematococcus pluvialis Extracts Regulate Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.-H.; Baek, S.J. Molecular Targets of Dietary Polyphenols with Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Yonsei Med. J. 2005, 46, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhi, T.; Han, P.; Li, S.; Xia, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Jia, Y.; Ma, A. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Walnut Protein–Derived Peptide Leucine-Proline-Phenylalanine in Lipopolysaccharide-Irritated RAW264.7 Cells. Food Agric. Immunol. 2021, 32, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.; Yoon, M.J.; Park, K.S. Chemical Transformation of Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis Improves Its Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 19120–19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wang, M.; Manzoor, M.F.; Aadil, R.M.; Tan, X.; Liu, Z. Comparison of Different Methods for Extracting the Astaxanthin from Haematococcus pluvialis: Chemical Composition and Biological Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, Z.; Bigham, A.; Sadeghi, S.; Dehdashti, S.M.; Rabiee, N.; Aledavish, A.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Nasseri, B.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Sharifi, E.; et al. Nanotechnology-Abetted Astaxanthin Formulations in Multimodel Therapeutic and Biomedical Applications. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Shi, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, X.; Kang, T.; Deng, W. Quercetin Suppresses Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression and Angiogenesis through Inactivation of P300 Signaling. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, I.; Frøkiær, J.; Nørregaard, R. Quercetin Attenuates Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression in Response to Acute Ureteral Obstruction. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2015, 308, F1297–F1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, K.; Nonaka, M.; Narahara, M.; Torii, I.; Kawaguchi, K.; Yoshikawa, T.; Kumazawa, Y.; Morikawa, S. Inhibitory Effect of Quercetin on Carrageenan-Induced Inflammation in Rats. Life Sci. 2003, 74, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-K.; Park, Y.-S.; Choi, D.-K.; Chang, H.-I. Effects of Astaxanthin on the Production of NO and the Expression of COX-2 and iNOS in LPS-Stimulated BV2 Microglial Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 1990–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Kim, Y.-S.; Song, H.S. Astaxanthin Ameliorates Atopic Dermatitis by Inhibiting the Expression of Signal Molecule NF-κB and Inflammatory Genes in Mice. J. Acupunct. Res. 2022, 39, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Yang, W.; Shao, W.; Pan, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kan, H.; Xu, Y.; Ying, Z. Deficiency of Interleukin-6 Receptor Ameliorates PM2.5 Exposure–Induced Pulmonary Dysfunction and Inflammation but Not Abnormalities in Glucose Homeostasis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 247, 114253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jiang, S.Y.; Wang, T.-Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhong, M.; Wang, A.; Lippmann, M.; Chen, L.-C.; Rajagopalan, S.; Sun, Q. Inflammatory Response to Fine Particulate Air Pollution Exposure: Neutrophil versus Monocyte. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidhindi, R.S.R.; Ambhore, N.S.; Sathish, V. Cellular and Biochemical Analysis of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid from Murine Lungs. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2223, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shou, Q.; Ding, Z. PM2.5 Exposure Induces Inflammatory Response in Macrophages via the TLR4/COX-2/NF-κB Pathway. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, W.-C.; Lai, C.-Y.; Lin, H.-W.; Tu, D.-G.; Shen, T.-J.; Lee, Y.-J. Luteolin Attenuates PM2.5-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Augmenting HO-1 and JAK-STAT Expression in Murine Alveolar Macrophages. Food Agric. Immunol. 2022, 33, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Usatyuk, P.V.; Gorshkova, I.A.; He, D.; Wang, T.; Moreno-Vinasco, L.; Geyh, A.S.; Breysse, P.N.; Samet, J.M.; Spannhake, E.W.; et al. Regulation of COX-2 Expression and IL-6 Release by Particulate Matter in Airway Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 40, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-C. Theoretical Basis, Experimental Design, and Computerized Simulation of Synergism and Antagonism in Drug Combination Studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.G.; Hwang, J.W.; Kang, H. Antioxidant and Skin-Whitening Efficacy of a Novel Decapeptide (DP, KGYSSYICDK) Derived from Fish By-Products. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid Colorimetric Assay for Cellular Growth and Survival: Application to Proliferation and Cytotoxicity Assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, L.C.; Wagner, D.A.; Glogowski, J.; Skipper, P.L.; Wishnok, J.S.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Analysis of Nitrate, Nitrite, and [15N]Nitrate in Biological Fluids. Anal. Biochem. 1982, 126, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva Moreno, M.I.; Isla, M.I.; Sampietro, A.R.; Vattuone, M.A. Comparison of the Free Radical-Scavenging Activity of Propolis from Several Regions of Argentina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 71, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Contents |

|---|---|

| Total Polyphenol Content (TPC) | 1185.49 ± 20.35 mg GAE/g 1,3 |

| Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) | 56.29 ± 11.87 mg QE/g 2,3 |

| Celecoxib Pose ID | RMSD (Å) | Celecoxib Pose ID | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.4610 | 13 | 6.1187 |

| 2 | 0.6477 | 14 | 6.8377 |

| 3 | 0.8432 | 15 | 5.1316 |

| 4 | 0.9605 | 16 | 6.1564 |

| 5 | 4.9750 | 17 | 7.0174 |

| 6 | 0.8623 | 18 | 5.1730 |

| 7 | 5.5747 | 19 | 6.8061 |

| 8 | 0.9668 | 20 | 6.9348 |

| 9 | 5.5523 | 21 | 6.8886 |

| 10 | 6.0899 | 22 | 6.5071 |

| 11 | 5.5572 | 23 | 1.7841 |

| 12 | 6.1417 |

| Ligand | Binding Site ID | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Key Interacting Residues | Type of Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib | Co-crystallized active site | −11.427 | Arg499, Leu338, Phe504, Arg106 | Hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking |

| Quercetin | Co-crystallized active site | −9.501 | Hie75, Gln178, Leu338, Tyr371, Ser516 | Hydrogen bonding |

| Astaxanthin | Predicted binding site 1 | −8.753 | Ala142 | Hydrogen bonding |

| Sample NO. | NO. 1 | NO. 2 | NO. 3 | NO. 4 | NO. 5 | NO. 6 | NO. 7 | NO. 8 | NO. 9 | NO. 10 | NO. 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio (H 1:W 2) | 10:0 | 9:1 | 8:2 | 7:3 | 6:4 | 5:5 | 4:6 | 3:7 | 2:8 | 1:9 | 0:10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, H.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, S.-G. Synergistic Protective Effects of Haematococcus pluvialis-Derived Astaxanthin and Walnut Shell Polyphenols Against Particulate Matter (PM)2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120473

Kang H, Choi J-H, Lee S-G. Synergistic Protective Effects of Haematococcus pluvialis-Derived Astaxanthin and Walnut Shell Polyphenols Against Particulate Matter (PM)2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120473

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Hyun, Jae-Ho Choi, and Sung-Gyu Lee. 2025. "Synergistic Protective Effects of Haematococcus pluvialis-Derived Astaxanthin and Walnut Shell Polyphenols Against Particulate Matter (PM)2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120473

APA StyleKang, H., Choi, J.-H., & Lee, S.-G. (2025). Synergistic Protective Effects of Haematococcus pluvialis-Derived Astaxanthin and Walnut Shell Polyphenols Against Particulate Matter (PM)2.5-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120473