Trimethyl Chitosan-Engineered Cod Skin Peptide Nanosystems Alleviate Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in D-Galactose-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Preparation and Characterization of CSCPs-NPs

2.2. CSCPs-NPs Mitigate Hippocampal Atrophy and Neuronal Damage

2.3. CSCPs-NPs Improve Cognitive and Motor Functions in AD Mice

2.4. CSCPs-NPs Restore Apoptotic Balance in the Hippocampus

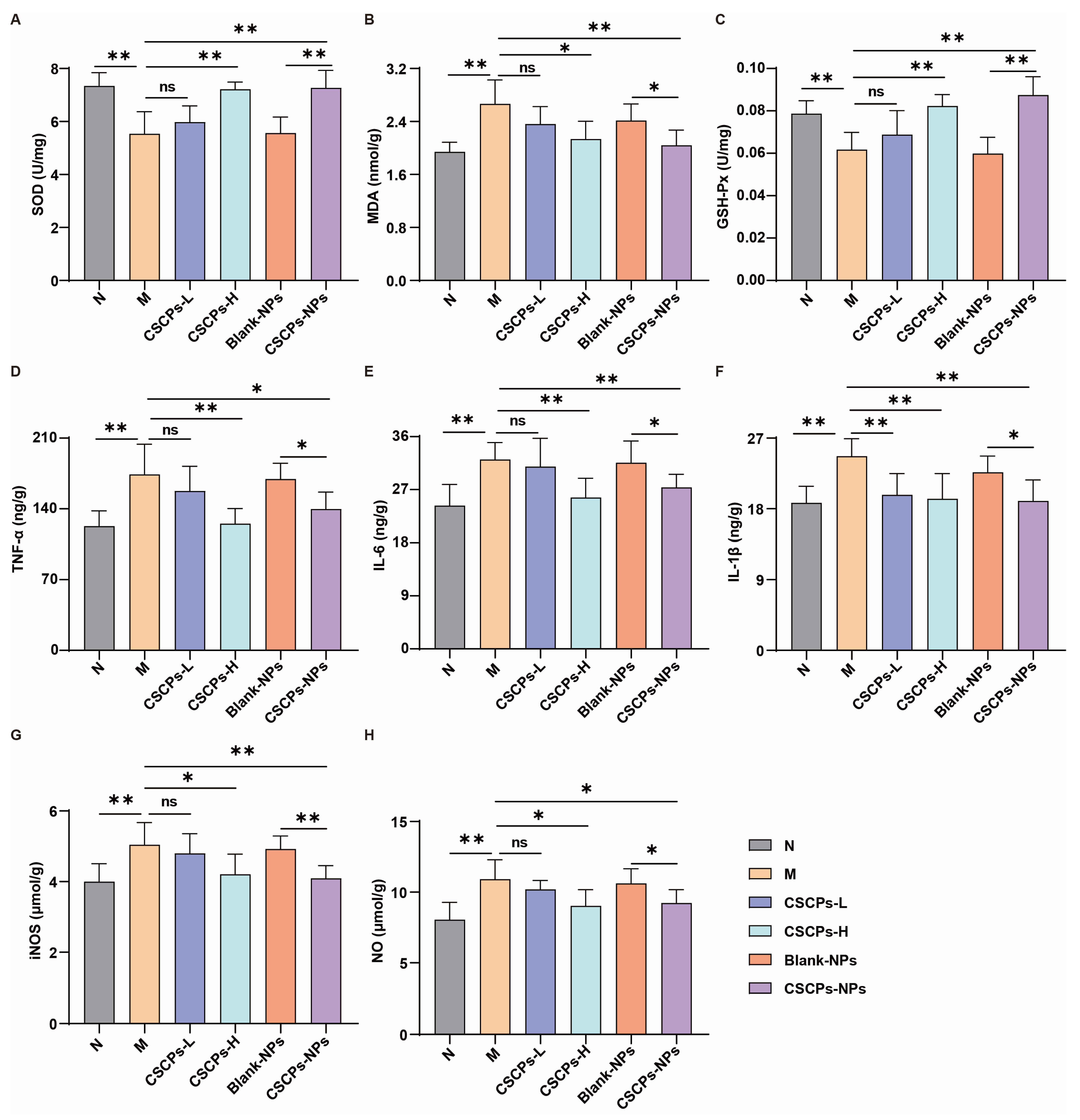

2.5. CSCPs-NPs Alleviate Oxidative Stress and Neuroinflammation via ROS/NF-κB Pathway

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of Trimethyl Chitosan (TMC)

4.2. Preparation and Characterization of CSCP-Loaded TMC Nanoparticles (CSCPs-NPs)

4.3. In Vitro Release Study

4.4. Animals and Drug Administration

4.5. Behavioral Tests

4.6. Histopathological Examination

4.7. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

4.8. ELISA

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CSCPs | Cod skin collagen peptides |

| TMC | Trimethyl chitosan |

| CSCPs-NPs | Trimethyl chitosan (TMC)-based CSCP-loaded nanoparticles |

References

- Scheltens, P.; De Strooper, B.; Kivipelto, M.; Holstege, H.; Chételat, G.; Teunissen, C.E.; Cummings, J.; van der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennol, M.P.; Bordier, C.; Kamelher, L.; Ulrich, J.D.; Holtzman, D.M.; Gratuze, M. ApoE-calypse tau: ApoE-tau synergy in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20250965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.T.; Del Tredici, K.; Barthélemy, N.R.; Gabitto, M.; van Dyck, C.H.; Lein, E.; Braak, H.; Datta, D. An integrated view of the relationships between amyloid, tau, and inflammatory pathophysiology in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Morgan, D.; Jessen, F. Passive anti-amyloid β immunotherapy in Alzheimer’s disease-opportunities and challenges. Lancet 2024, 404, 2198–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, R.; Sterling, K.; Song, W. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: Challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Domenico, F.; Pupo, G.; Giraldo, E.; Badìa, M.-C.; Monllor, P.; Lloret, A.; Schininà, M.E.; Giorgi, A.; Cini, C.; Tramutola, A.; et al. Oxidative signature of cerebrospinal fluid from mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease patients. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; van der Flier, W.M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D.R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A.H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zong, S. The roles of microglia and astrocytes in neuroinflammation of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1575453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wu, W.; Wen, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhao, C. Potential therapeutic natural compounds for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Phytomedicine 2024, 132, 155822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, S.; Yarmohammadi, A.; Yarmohammadi, M.; Farzaei, M.H.; Echeverria, J. Marine Natural Products: Promising Candidates in the Modulation of Gut-Brain Axis towards Neuroprotection. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yang, X.-N.; Dong, Y.-X.; Han, Y.-J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Zhou, X.-L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Fang, J.-S.; Ji, J.-L.; et al. The potential therapeutic strategy in combating neurodegenerative diseases: Focusing on natural products. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 264, 108751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Chai, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; He, L.; Sang, Z.; Chen, D.; Zheng, X. The Advancements of Marine Natural Products in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Study Based on Cell and Animal Experiments. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Lin, S.; Gao, D.; Hu, J.; Bao, Z. Fish scale collagen peptide improves neurodegenerative disorders by dual regulation of acetylcholinesterase activity and antioxidant defense system. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 8651–8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wu, T.; Chen, N. Bridging neurotrophic factors and bioactive peptides to Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 94, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Yang, Q.; Hong, H.; Feng, L.; Liu, J.; Luo, Y. Physicochemical and functional properties of Maillard reaction products derived from cod (Gadus morhua L.) skin collagen peptides and xylose. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.; Sousa, R.O.; Carvalho, A.C.; Alves, A.L.; Marques, C.F.; Cerqueira, M.T.; Reis, R.L.; Silva, T.H. Potential of Atlantic Codfish (Gadus morhua) Skin Collagen for Skincare Biomaterials. Molecules 2023, 28, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Xi, Y.; Li, H. Anti-photoaging activity of cod peptides: Structural characterisation and clinical validation. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 7972–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Hou, H. Typical structure, biocompatibility, and cell proliferation bioactivity of collagen from Tilapia and Pacific cod. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 210, 112238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S.; Lv, L.; Guo, J.; Yang, X.; Liao, M.; Zhao, T.; Sun, H.; Zhang, S.; Li, W. Preparation of Cod Skin Collagen Peptides/Chitosan-Based Temperature-Sensitive Gel and Its Anti-Photoaging Effect in Skin. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2023, 17, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, G.G.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, X.Z.; Wang, Y. Anti-inflammatory activity of collagen peptide in vitro and its effect on improving ulcerative colitis. NPJ Sci. Food 2025, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ren, Y.; Ren, T.; Yu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, X. Marine-Derived Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review of Their Therapeutic Potential in Oxidative Stress-Associated Diseases. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, Y. Recent advances of chitosan-based nanoparticles for biomedical and biotechnological applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 203, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, A.D.; Patel, H.M.; Surana, S.J.; Vanjari, Y.H.; Belgamwar, V.S.; Pardeshi, C.V. N,N,N-Trimethyl chitosan: An advanced polymer with myriad of opportunities in nanomedicine. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 875–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lv, H.; Chen, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Luo, L.; Guan, X. N-trimethyl chitosan coated targeting nanoparticles improve the oral bioavailability and antioxidant activity of vitexin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-M.; Wu, L.-J.; Lin, M.-T.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Wang, T.-T.; Han, M.; Zhang, B.; Xu, D.-H. Construction and Evaluation of Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles for Oral Administration of Exenatide in Type 2 Diabetic Rats. Polymers 2022, 14, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Dhapola, R.; Reddy, D.H. Apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: Insight into the signaling pathways and therapeutic avenues. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obulesu, M.; Lakshmi, M.J. Apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease: An understanding of the physiology, pathology and therapeutic avenues. Neurochem. Res. 2014, 39, 2301–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Britto, D.; Assis, O.B. A novel method for obtaining a quaternary salt of chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.J.; Zhang, Z.R.; Song, Q.G.; He, Q. Research on thymopentin loaded oral N-trimethyl chitosan nanoparticles. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006, 29, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kong, S.; Lv, L.; Guo, J.; Lu, G.; Li, D.; Zhou, X. Trimethyl Chitosan-Engineered Cod Skin Peptide Nanosystems Alleviate Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in D-Galactose-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120472

Kong S, Lv L, Guo J, Lu G, Li D, Zhou X. Trimethyl Chitosan-Engineered Cod Skin Peptide Nanosystems Alleviate Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in D-Galactose-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):472. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120472

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Songzhi, Lijiao Lv, Jiaqi Guo, Guiping Lu, Dongdong Li, and Xin Zhou. 2025. "Trimethyl Chitosan-Engineered Cod Skin Peptide Nanosystems Alleviate Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in D-Galactose-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120472

APA StyleKong, S., Lv, L., Guo, J., Lu, G., Li, D., & Zhou, X. (2025). Trimethyl Chitosan-Engineered Cod Skin Peptide Nanosystems Alleviate Behavioral and Cognitive Deficits in D-Galactose-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Mice. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 472. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120472