Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungi from Suaeda glauca in the Yellow River Delta and Their Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungal Community of S. glauca

2.1.1. Rhizosphere Soil Physicochemical Factors

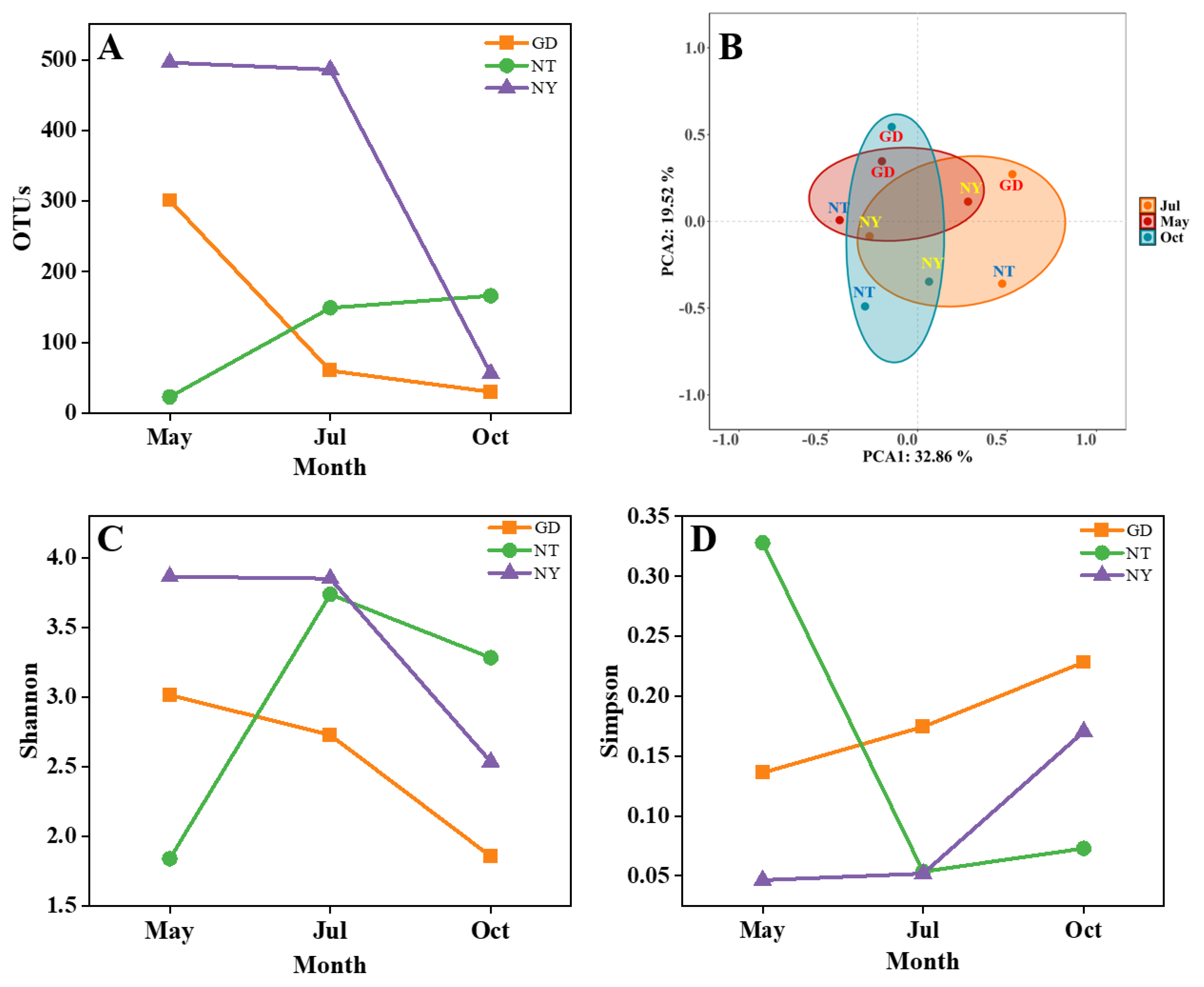

2.1.2. Rhizosphere Fungal Diversity

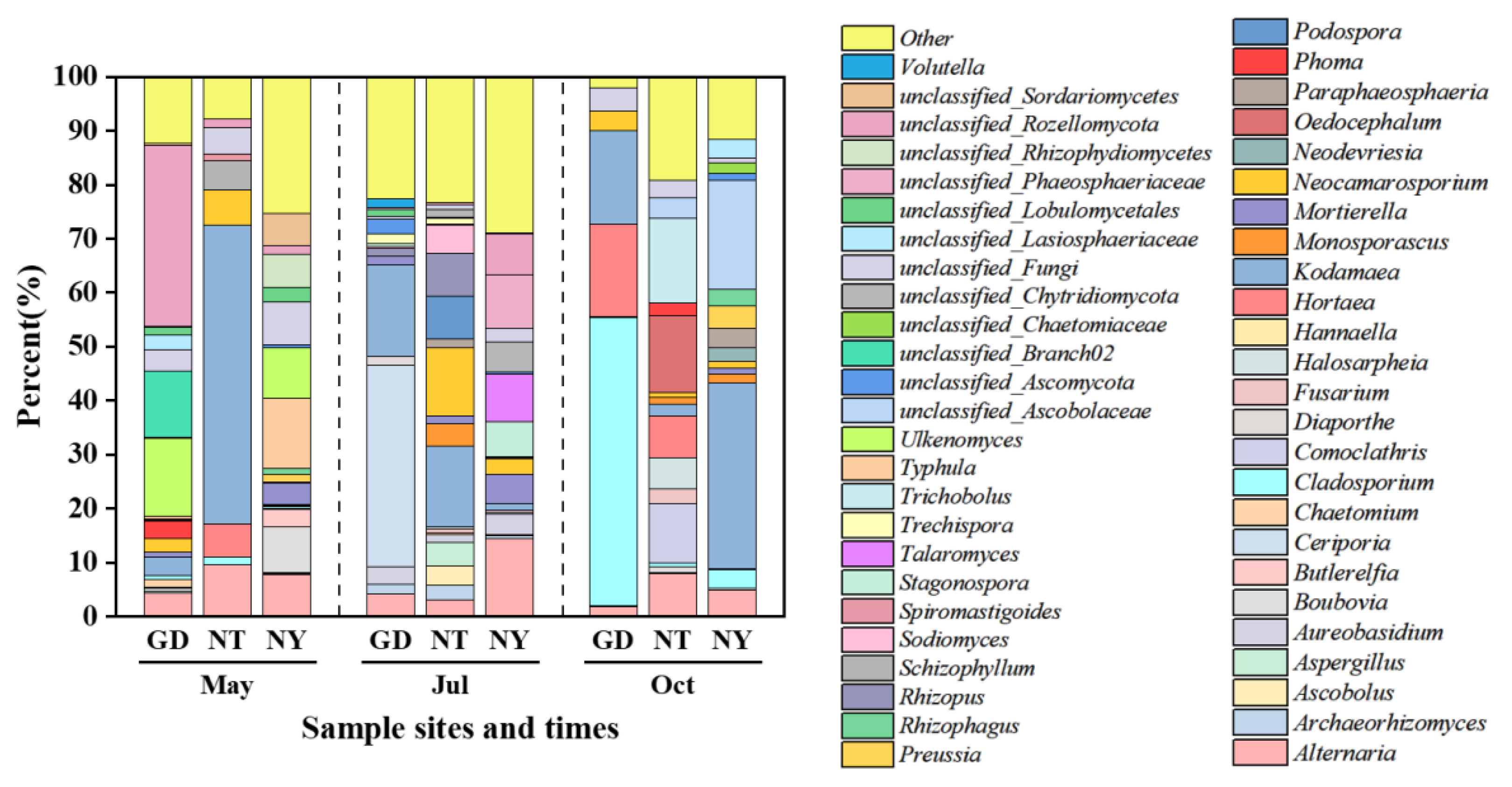

2.1.3. Rhizosphere Fungal Community Structure

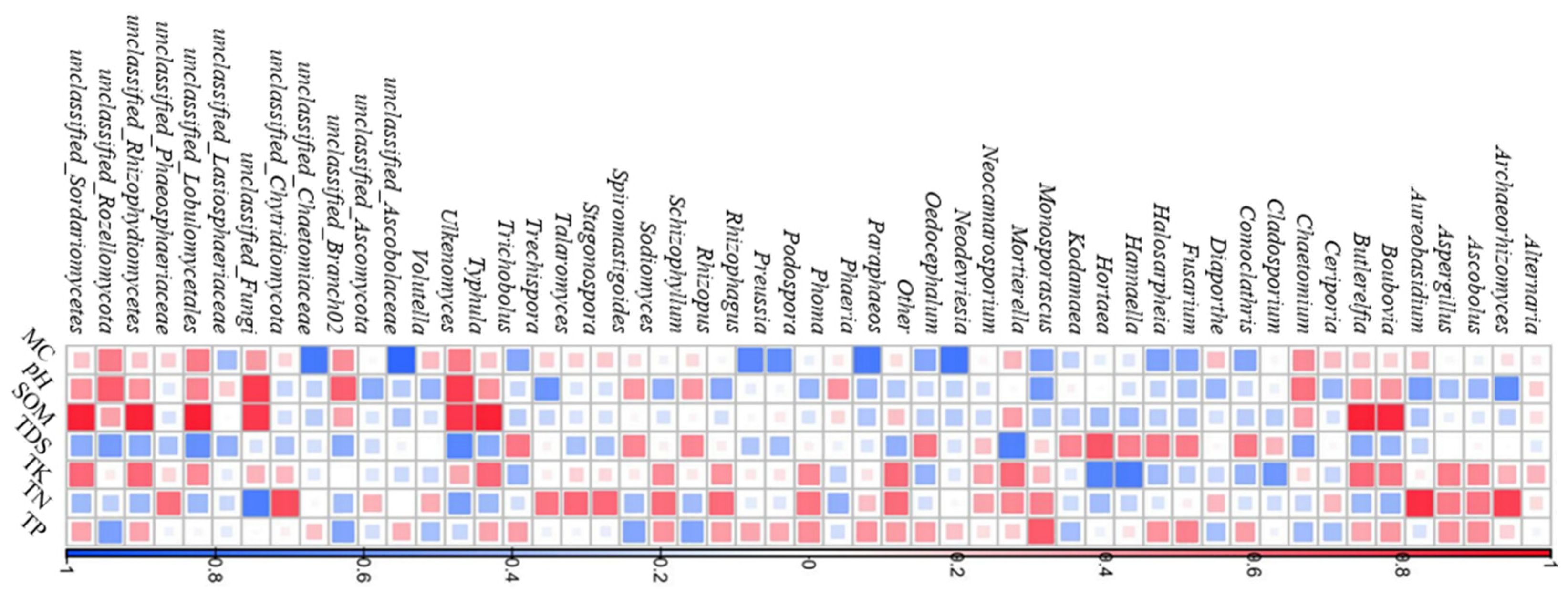

2.1.4. Relationship Between Fungal Diversity and Soil Physicochemical Factors

2.2. Biodiversity of Cultivable Rhizosphere Fungi of S. glauca

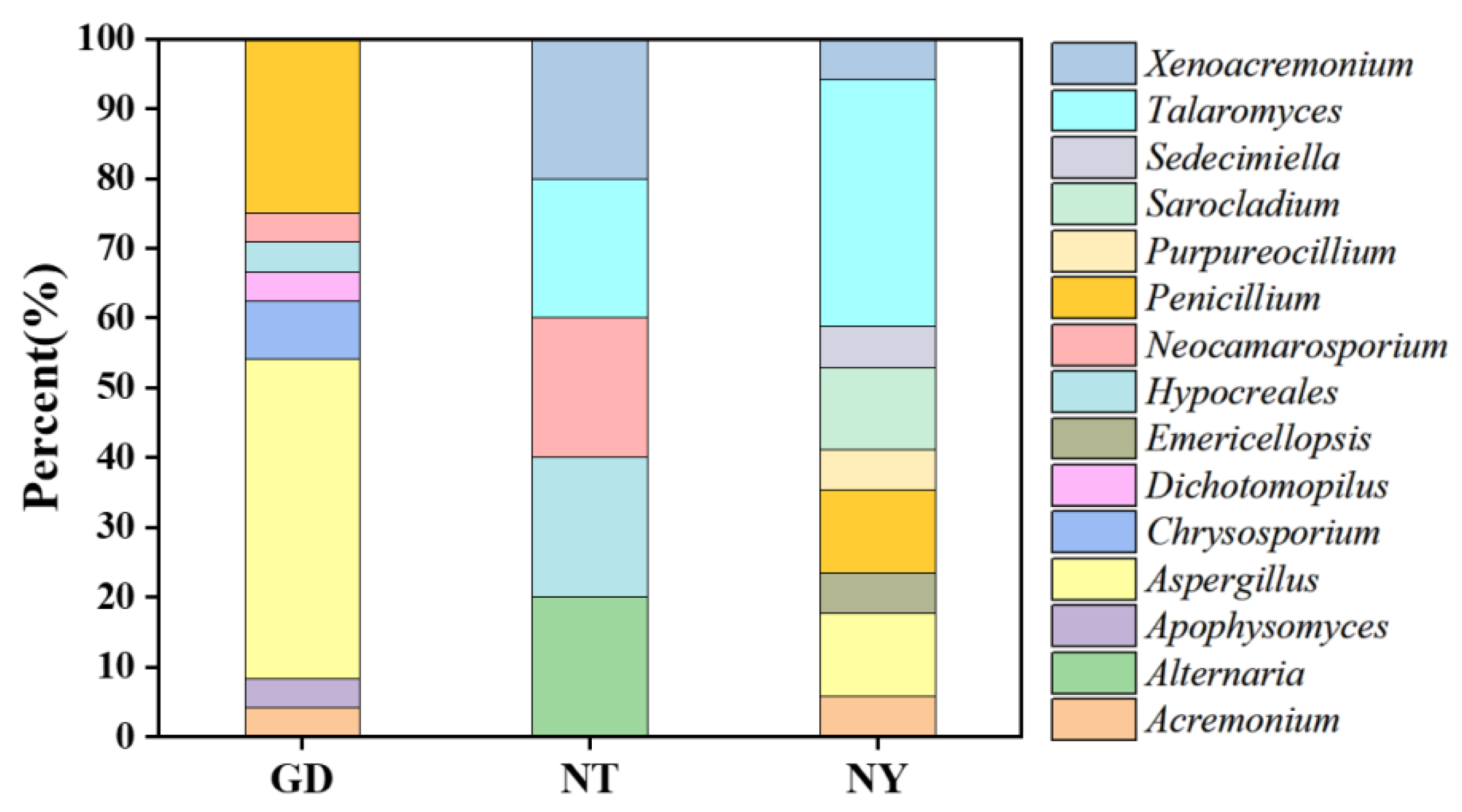

2.2.1. Isolation and Identification of Cultivable Rhizosphere Fungi

2.2.2. Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials of Isolated Fungi

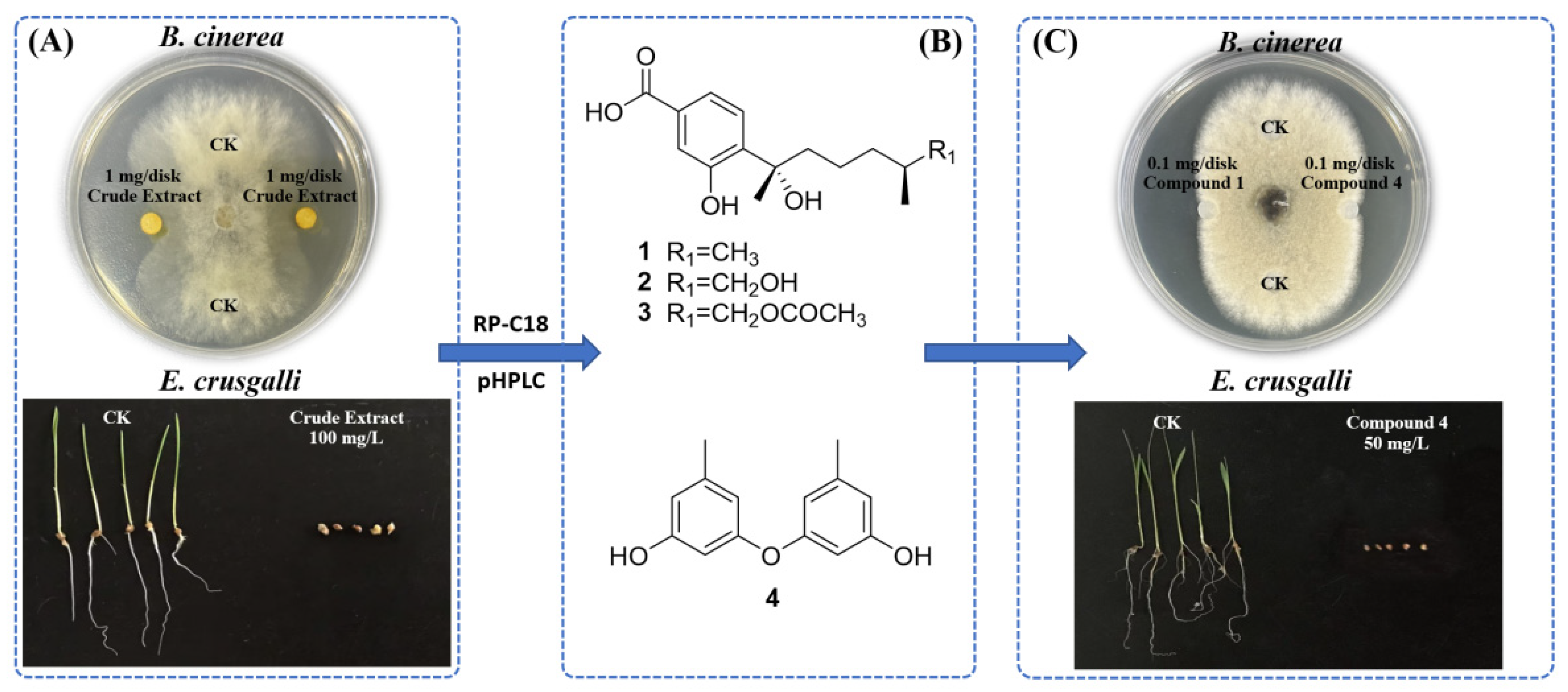

2.3. Bioassay-Guided Isolation of A. tabacinus GD-25

3. Materials and Methods

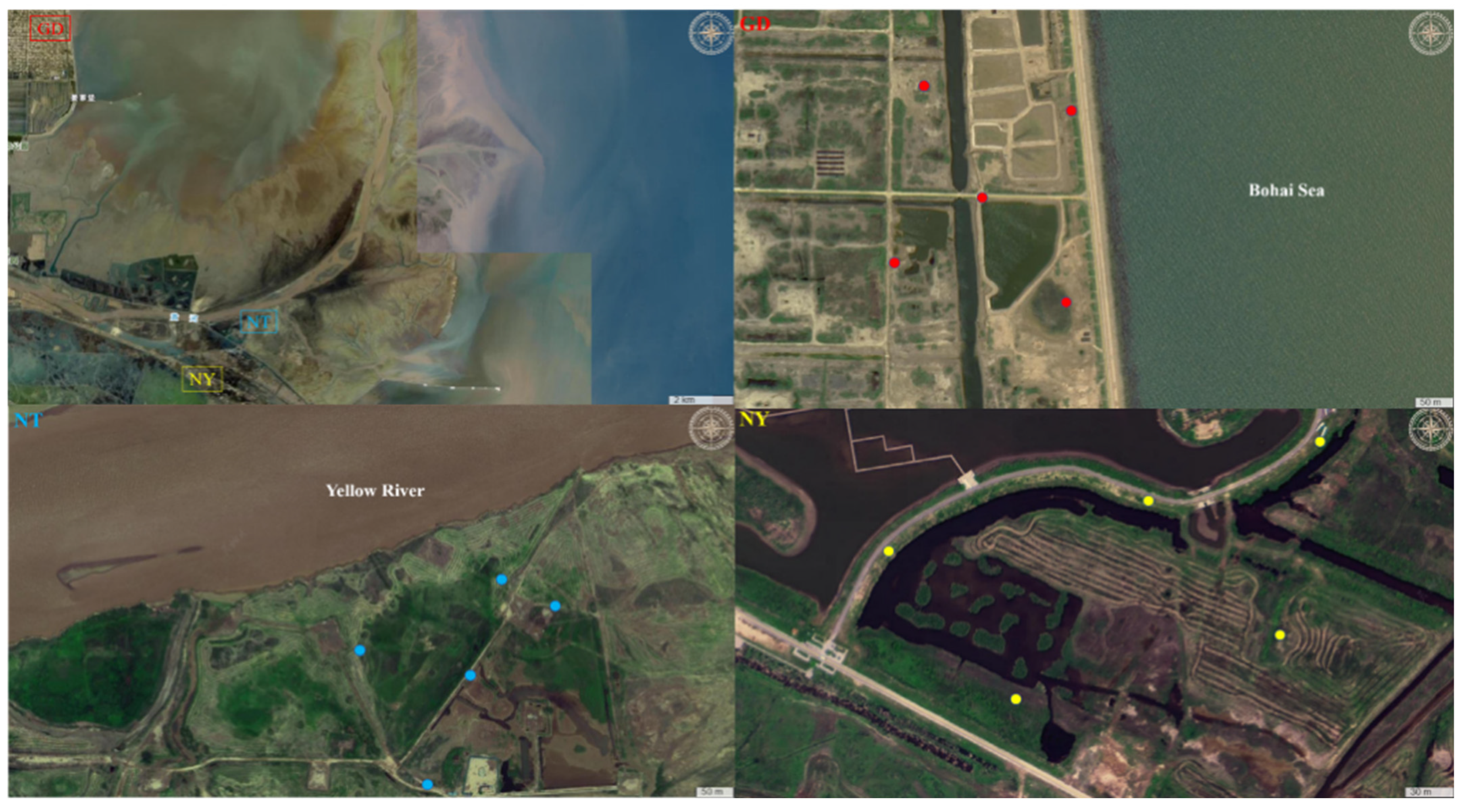

3.1. Description of Sampling Sites

3.2. High-Throughput Sequencing and Analysis of Fungal Community Diversity

3.3. Soil Physiochemical Factors

3.4. Isolation of Fungal Strains from S. glauca Rhizosphere Soil

3.5. Identification of Fungal Strain

3.6. Antifungal and Herbicidal Evaluations

3.7. Fermentation, Extraction and Bioassay-Guided Isolation of A. tabacinus GD-25

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, X.T.; Cui, Q.H.; Li, D.Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, Z.Q. Characteristics of soil microbial community structure in different land use types of the Huanghe alluvial plain. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, K. Effect of intertidal vegetation (Suaeda salsa) restoration on microbial diversity in the offshore areas of the Yellow River Delta. Plants 2024, 13, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Hu, S.X.; Liu, X.X.; Zang, Y.; Chen, J.; Gao, N.; Li, L.Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.X.; Xu, J.K.; et al. Effects of Spartina alterniflora invasion on the community structure and diversity of wetland soil bacteria in the Yellow River Delta. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, E.; Yang, X.; Yang, J. Shifts in microbial community structure and co-occurrence network along a wide soil salinity gradient. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lv, D.T.; Jiang, S.Y.; Lin, H.; Sun, J.Q.; Li, K.J.; Sun, J. Soil salinity regulation of soil microbial carbon metabolic function in the Yellow River Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, J.H.; Peng, Z.P.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Men, M.X. Accuracy analysis of remote sensing index enhancement for SVM salt inversion model. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 2406–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; He, R.; Tian, C.Y.; Song, J. Utilization of halophytes in saline agriculture and restoration of contaminated salinized soils from genes to ecosystem: Suaeda salsa as an example. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 197, 115728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, B.; Chen, M. Recent progress on the salt tolerance mechanisms and application of tamarisk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.X. Genetic mechanisms of salt stress responses in halophytes. Plant Signal. Behav. 2019, 15, 1704528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D.; Sun, Q.H.; Liu, J.A.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, N.; Gao, Z. Suaeda salsa root-associated microorganisms could effectively improve maize growth and resistance under salt stress. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0134922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Gong, X.W.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, W.Z.; Sun, J.; Chen, B.L. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on photosynthesis, ion balance of tomato plants under saline-alkali soil condition. J. Plant Nutr. 2019, 43, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Jiang, Z.H.; Xiang, Z.W.; Zhou, A.F.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhou, F.Z. Genomic features of a plant growth-promoting endophytic Enterobacter cancerogenus JY65 dominant in microbiota of halophyte Suaeda salsa. Plant Soil 2023, 496, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Niu, H.J.; Qu, T.L.; Zhang, X.F.; Du, F.Y. Streptomyces sp. FX13 inhibits fungicide-resistant Botrytis cinerea in vitro and in vivo by producing oligomycin A. Pestic. Biochem. Phys. 2021, 175, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.F.; Zhang, W.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, Y.M.; Du, F.Y. Characterization and bioactive potentials of secondary metabolites from Fusarium chlamydosporum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 889–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.F.; Sun, Z.C.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, Y.M.; Du, F.Y. Herbicidal polyketides and diketopiperazine derivatives from Penicillium viridicatum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 14102–14109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhter, N.; Pan, C.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.T.; Wu, B. Isolation and structure determination of a new indene derivative from endophytic fungus Aspergillus flavipes Y-62. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 33, 2939–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, X.G.; Song, L.C.; Han, M.; Xiao, Y.N. Diversity of endophytic fungi of Suaeda heteroptera Kitag. Microbiol. China 2012, 39, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.Q.; Li, J.; Liu, J.P.; Xiao, S.Y.J.; Yang, S.M.; Mei, J.H.; Ren, M.Y.; Wu, S.Z.; Zhang, H.Y.; Yang, X.L. Secondary metabolites of Alternaria: A comprehensive review of chemical diversity and pharmacological properties. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1085666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.K.; Dufosse, L.; Chhipa, H.; Saxena, S.; Mahajan, G.B.; Gupta, M.K. Fungal endophytes: A potential source of antibacterial compounds. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, K.; Huang, Z.D.; Shi, S.P.; Pan, W.D.; Zhang, Y.L. Diversity, antibacterial and phytotoxic activities of culturable endophytic fungi from Pinellia pedatisecta and Pinellia ternate. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Wang, B.; Tian, K.L.; Ji, W.X.; Zhang, T.Y.; Ping, C.; Yan, W.; Ye, Y.H. Novel metabolites from the Cercis chinensis derived endophytic fungus Alternaria alternata ZHJG5 and their antibacterial activities. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2264–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.Y.; Ju, G.L.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, Y.M.; Wu, X. Sesquiterpenes and cyclodepsipeptides from marine-derived fungus Trichoderma longibrachiatum and their antagonistic activities against soil-borne pathogens. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Ju, G.L.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, X.F.; Du, F.Y. Cyclodepsipeptides and sesquiterpenes from marine-derived fungus Trichothecium roseum and their biological functions. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.Z.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, C.R.; He, Y.Q.; Zhang, L.M. Microbial composition and diversity of an upland red soil under long-term fertilization treatments as revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. J. Soils Sediments 2008, 8, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.M.; He, X.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Feng, S.Z.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.B.; Zhao, Z.W.; Su, Y.R. Influence of plant communities and soil properties during natural vegetation restoration on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in a karst region. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Hu, X.; Kang, Y.; Xie, C.; Shen, Q. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities in the rhizospheric soil of litchi and mango orchards as affected by geographic distance, soil properties and manure input. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 152, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipper, L.A.; Degens, B.P.; Sparling, G.P.; Duncan, L.C. Changes in microbial heterotrophic diversity along five plant successional sequences. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 2093–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setälä, H.; Mclean, M.A. Decomposition rate of organic substrates in relation to the species diversity of soil saprophytic fungi. Oecologia 2004, 139, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.Y.; Jia, J.; Bi, H.K.; Liang, J.Y.; Liu, L. Research on secondary metabolites and their activities from a marine fungus Aspergillus sp. WJP1. Chin. J. Mar. Drugs 2022, 41, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.Y.; Zhu, H.J.; Fu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.H.; Lin, H.P.; Liu, P.P.; Zhuang, Y.B.; Hong, K.; Zhu, W.M. Cytotoxic polyphenols from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium expansum. J. Nat. Prod. 2010, 73, 911–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Li, X.X.; Chen, G.D.; Gao, H.; Guo, L.D.; Yao, X.S. A new diphenyl ether from an endolichenic fungal strain, Aspergillus sp. Mycosystema 2012, 31, 769–774. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.V.; Han, J.W.; Kim, H.; Choi, G.J. Phenyl ethers from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus tabacinus and their antimicrobial activity against plant pathogenic fungi and bacteria. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 33273–33279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.H.; Feng, Z.Q.; Liu, J.H.; Wang, Y.; Shang, S.; Xu, J.K.; Liu, T.; Liu, L.X. Effects of salt stress on the rhizosphere soil microbial communities of Suaeda salsa (L.) Pall. in the Yellow River Delta. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.L.; Yu, X.W.; Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, Y.R.; Chen, C.M.; Li, L.; Fan, S.M.; Lu, X.R.; Zhang, X.J. Effect of compost as a soil amendment on the structure and function of fungal diversity in saline–alkali soil. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2025, 9, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.L.; Yu, X.W.; Yang, J.B.; Zhao, X.P.; Bao, Y.Y. High-Throughput sequencing reveals the diversity and community structure in rhizosphere soils of three endangered plants in Western Ordos, China. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2713–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Shao, W.; Dong, Q.; Ji, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, A.; Chen, C.; Yao, W. The effects of acid-modified biochar and biomass power plant ash on the physiochemical properties and bacterial community structure of sandy alkaline soils in the ancient region of the Yellow River. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.K.; Zhou, Y.M.; Zhu, N.; Guo, X.P.; Luo, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Leng, F.F.; Wang, Y.G. Soil organic matter and total nitrogen reshaped root-associated bacteria community and synergistic change the stress resistance of Codonopsis pilosula. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 2545–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.G. Principles and Methods of Soil Microbiology Research, 2nd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, N.X.; Liang, Z.Y.; Liu, Q.; Tu, C.D.; Dong, K.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Chen, M. Antifungal secondary metabolites isolated from mangrove rhizosphere soil-derived Penicillium fungi. Chin. J. Mar. Drugs 2020, 19, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, J.T.; Cao, D.F.; Li, H.; Fang, H.Y.; Qu, T.L.; Zhang, B.H.; Li, S.S.; Du, F.Y. Biocontrol potential and antifungal mechanism of a novel Bacillus velezensis NH-13-5 against Botrytis cinerea causing postharvest gray mold in table grapes. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 229, 113710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, J.; Fan, Z. Structure-Based Discovery and synthesis of potential transketolase inhibitors. Molecules 2018, 23, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadha, S.; Kale, S.P. Simple fluorescence-based high throughput cell viability assay for filamentous fungi. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qu, T.-L.; Li, H.; Cao, D.-F.; Li, M.-Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Zhang, B.-H.; Xiao, L.; Du, F.-Y. Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungi from Suaeda glauca in the Yellow River Delta and Their Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120460

Qu T-L, Li H, Cao D-F, Li M-Y, Zhao C, Zhang L-Y, Zhang B-H, Xiao L, Du F-Y. Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungi from Suaeda glauca in the Yellow River Delta and Their Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120460

Chicago/Turabian StyleQu, Tian-Li, Hong Li, Dong-Fang Cao, Meng-Ya Li, Chen Zhao, Li-Yuan Zhang, Bao-Hua Zhang, Lin Xiao, and Feng-Yu Du. 2025. "Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungi from Suaeda glauca in the Yellow River Delta and Their Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120460

APA StyleQu, T.-L., Li, H., Cao, D.-F., Li, M.-Y., Zhao, C., Zhang, L.-Y., Zhang, B.-H., Xiao, L., & Du, F.-Y. (2025). Biodiversity of Rhizosphere Fungi from Suaeda glauca in the Yellow River Delta and Their Agricultural Antifungal and Herbicidal Potentials. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120460