A Journey into the Blue: Current Knowledge and Emerging Insights into Marine-Derived Peptaibols

Abstract

1. Introduction

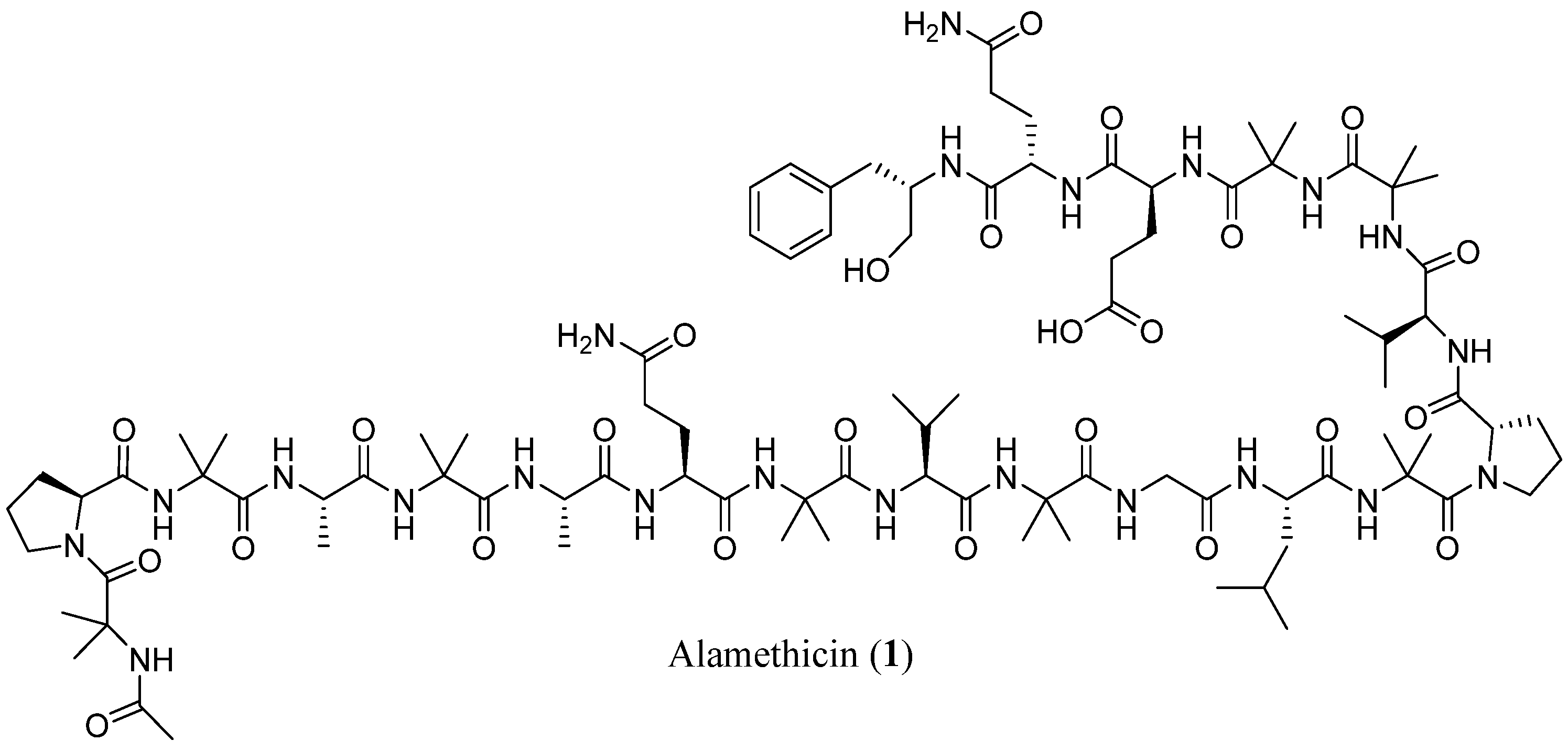

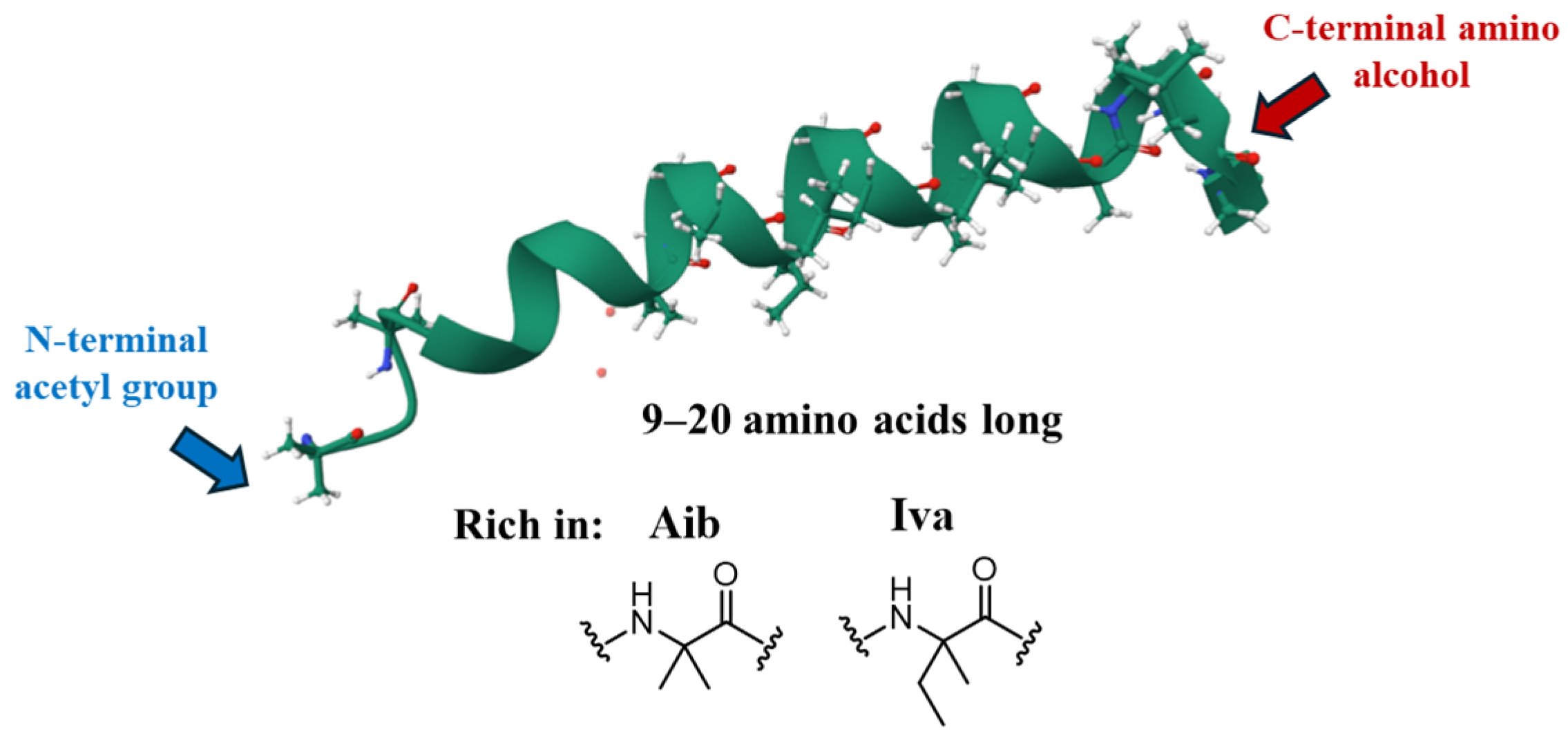

2. Chemodiversity, Classification and Occurrence

3. Biosynthesis

4. Bioactivity

5. Marine-Origin Species

5.1. Peptaibols in Marine Trichoderma Species

- Cluster 8.3 showed similarity with the biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) related to the production of harzianins HC and hypomuricins.

- Cluster 19.1 showed similarity with (BGCs) known to produce 18–20-residues peptaibols. The actual peptaibol composition was then annotated through an integrated approach, involving molecular network, manual inspection of the MS/MS spectra and phylogenetic analysis of the adenylation domain in order to predict the incorporation of specific or variable amino acid residues in each position. The study led to the tentative identification of 21 novel 15-residue peptaibols named Endophytins and a smaller family of 11- and 14-residue peptaibols.

- Module skipping (in cluster 8.3), allowing synthesis of variable-length peptaibols;

- Module loss (in cluster 19.1), a novel finding not previously reported in peptaibol synthesis.

5.2. Peptaibols in Marine Emericellopsis Species

5.3. Peptaibols in Marine Acremonium Species

5.4. Peptaibols in Other Marine Species

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sable, R.; Parajuli, P.; Jois, S. Peptides, Peptidomimetics, and Polypeptides from Marine Sources: A Wealth of Natural Sources for Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.; Sheridan, C.; Osinga, R.; Dionísio, G.; Rocha, R.; Silva, B.; Rosa, R.; Calado, R. Marine Microorganism-Invertebrate Assemblages: Perspectives to Solve the “Supply Problem” in the Initial Steps of Drug Discovery. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 3929–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez Ghoran, S.; Taktaz, F.; Sousa, E.; Fernandes, C.; Kijjoa, A. Peptides from Marine-Derived Fungi: Chemistry and Biological Activities. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenkolb, T.; Brückner, H. Peptaibiomics: Towards a Myriad of Bioactive Peptides Containing C α −Dialkylamino Acids? Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 1817–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S.; Ehrmann, B.M.; Adcock, A.F.; Kroll, D.J.; Carcache de Blanco, E.J.; Shen, Q.; Swanson, S.M.; Falkinham, J.O.; Wani, M.C.; Mitchell, S.M.; et al. Peptaibols from Two Unidentified Fungi of the Order Hypocreales with Cytotoxic, Antibiotic, and Anthelmintic Activities. J. Pept. Sci. 2012, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulard, C.; Hlimi, S.; Rebuffat, S.; Bodo, B. Trichorzins HA and MA, Antibiotic Peptides from Trichoderma harzianum. I. Fermentation, Isolation and Biological Properties. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 1248–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclohier, H.; Snook, C.F.; Wallace, B.A. Antiamoebin Can Function as a Carrier or as a Pore-Forming Peptaibol. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 1998, 1415, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres, A.; Leitgeb, B.; Kredics, L.; Antal, Z.; Hatvani, L.; Manczinger, L.; Vágvölgyi, C. Peptaibols and Related Peptaibiotics of Trichoderma. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2005, 52, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavryushina, I.A.; Georgieva, M.L.; Kuvarina, A.E.; Sadykova, V.S. Peptaibols as Potential Antifungal and Anticancer Antibiotics: Current and Foreseeable Development. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2021, 57, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Lin, M.; Kaliaperumal, K.; Lu, Y.; Qi, X.; Jiang, X.; Xu, X.; Gao, C.; Liu, Y.; Luo, X. Recent Advances in Anti-Inflammatory Compounds from Marine Microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chugh, J.K.; Wallace, B.A. Peptaibols: Models for Ion Channels. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001, 29, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Sun, R.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, T.; Che, Q.; Zhang, G.; Li, D. Peptaibols: Diversity, Bioactivity, and Biosynthesis. Eng. Microbiol. 2022, 2, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, C.P.; Komoń-Zelazowska, M.; Sándor, E.; Druzhinina, I.S. Facts and Challenges in the Understanding of the Biosynthesis of Peptaibols by Trichoderma. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1068–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Dias, L.; Oliveira-Pinto, P.R.; Fernandes, J.O.; Regalado, L.; Mendes, R.; Teixeira, C.; Mariz-Ponte, N.; Gomes, P.; Santos, C. Peptaibiotics: Harnessing the Potential of Microbial Secondary Metabolites for Mitigation of Plant Pathogens. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 68, 108223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turaga, V.N.R. Peptaibols: Antimicrobial Peptides from Fungi. In Bioactive Natural products in Drug Discovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 713–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.E.; Reusser, F. A Polypeptide Antibacterial Agent Isolated from Trichoderma viride. Experientia 1967, 23, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoppacher, N.; Neumann, N.K.N.; Burgstaller, L.; Zeilinger, S.; Degenkolb, T.; Brückner, H.; Schuhmacher, R. The Comprehensive Peptaibiotics Database. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann, N.K.N.; Stoppacher, N.; Zeilinger, S.; Degenkolb, T.; Brückner, H.; Schuhmacher, R. The Peptaibiotics Database—A Comprehensive Online Resource. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, T.; Tyagi, C.; Balázs, D.; Urbán, P.; Szepesi, Á.; Bakacsy, L.; Endre, G.; Rakk, D.; Szekeres, A.; Andersson, M.A.; et al. Structural Diversity and Bioactivities of Peptaibol Compounds from the Longibrachiatum Clade of the Filamentous Fungal Genus Trichoderma. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, T.; Tyagi, C.; Racić, G.; Rakk, D.; Szekeres, A.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Kredics, L. New 19-Residue Peptaibols from Trichoderma Clade Viride. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, T.; Urbán, P.; Tyagi, C.; Szekeres, A.; Leitgeb, B.; Vágvölgyi, M.; Manczinger, L.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Kredics, L. Diversity Profile and Dynamics of Peptaibols Produced by Green Mould Trichoderma Species in Interactions with Their Hosts Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus. Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoch, M.; Singh, D.; Kapoor, K.K.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Trichoderma Lixi (IIIM-B4), an endophyte of Bacopa Monnieri L. producing peptaibols. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-P.; Ji, N.-Y. Chemistry and Biology of Marine-Derived Trichoderma Metabolites. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, W.; Proksch, P.; Shao, B.; Lin, W. Sequential Determination of New Peptaibols Asperelines G-Z12 Produced by Marine-Derived Fungus Trichoderma asperellum Using Ultrahigh Pressure Liquid Chromatography Combined with Electrospray-Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1309, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroux, A.; Van Bohemen, A.; Roullier, C.; Robiou du Pont, T.; Vansteelandt, M.; Bondon, A.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A.; Pouchus, Y.F.; Ruiz, N. Unprecedented 17-Residue Peptaibiotics Produced by Marine-Derived Trichoderma atroviride. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 772–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, D.; Satou, T.; Senda, H.; Fujimaki, T.; Honda, R.; Kanazawa, S. Heptaibin, a Novel Antifungal Peptaibol Antibiotic from Emericellopsis sp. BAUA8289. J. Antibiot. 2000, 53, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flissi, A.; Ricart, E.; Campart, C.; Chevalier, M.; Dufresne, Y.; Michalik, J.; Jacques, P.; Flahaut, C.; Lisacek, F.; Leclère, V.; et al. Norine: Update of the Nonribosomal Peptide Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D465–D469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Hilário, S.; Van de Peer, Y.; Esteves, A.C.; Alves, A. Genomic and Metabolomic Analyses of the Marine Fungus Emericellopsis Cladophorae: Insights into Saltwater Adaptability Mechanisms and Its Biosynthetic Potential. J. Fungi 2021, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

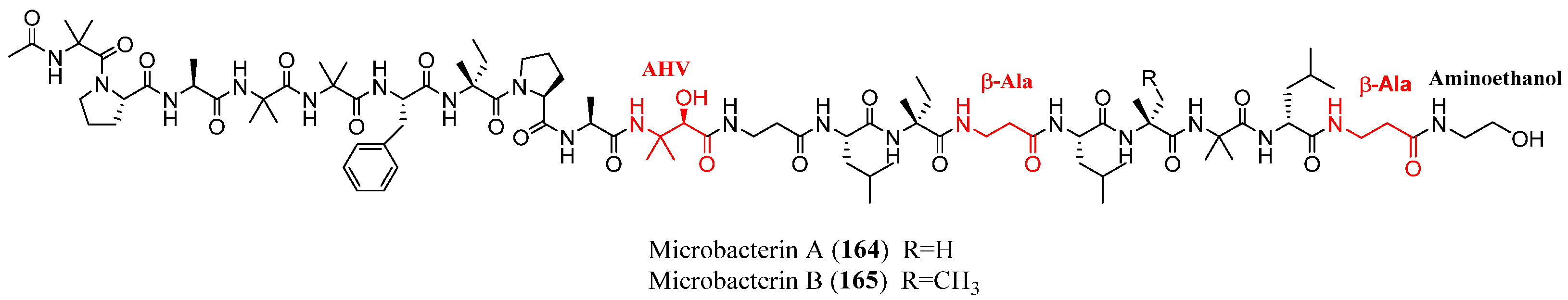

- Liu, D.; Lin, H.; Proksch, P.; Tang, X.; Shao, Z.; Lin, W. Microbacterins A and B, New Peptaibols from the Deep Sea Actinomycete Microbacterium Sediminis sp. Nov. YLB-01(T). Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.S.; Sousa, T.F.; da Silva, G.F.; Pedroso, R.C.N.; Menezes, K.S.; Soares, M.A.; Dias, G.M.; Santos, A.O.; Yamagishi, M.E.B.; Faria, J.V.; et al. Characterization of Peptaibols Produced by a Marine Strain of the Fungus Trichoderma Endophyticum via Mass Spectrometry, Genome Mining and Phylogeny-Based Prediction. Metabolites 2023, 13, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinichich, A.A.; Krivonos, D.V.; Baranova, A.A.; Zhitlov, M.Y.; Belozerova, O.A.; Lushpa, V.A.; Vvedensky, A.V.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Kalganova, A.I.; Kudzhaev, A.M.; et al. Genome-Guided Metabolomic Profiling of Peptaibol-Producing Trichoderma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiest, A.; Grzegorski, D.; Xu, B.-W.; Goulard, C.; Rebuffat, S.; Ebbole, D.J.; Bodo, B.; Kenerley, C. Identification of Peptaibols from Trichoderma virens and Cloning of a Peptaibol Synthetase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 20862–20868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Wiest, A.; Ruiz, N.; Keightley, A.; Moran-Diez, M.E.; McCluskey, K.; Pouchus, Y.F.; Kenerley, C.M. Two Classes of New Peptaibols Are Synthesized by a Single Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase of Trichoderma virens. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 4544–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Dhar, R.; Sen, R. Designer Bacterial Cell Factories for Improved Production of Commercially Valuable Non-Ribosomal Peptides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 60, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ben Haj Salah, K.; Djibo, M.; Inguimbert, N. Peptaibols as a Model for the Insertions of Chemical Modifications. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 658, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Torre, C.; Sannio, F.; Battistella, M.; Docquier, J.-D.; De Zotti, M. Peptaibol Analogs Show Potent Antibacterial Activity against Multidrug Resistant Opportunistic Pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ben Salah, K.H.; Wenger, E.; Legrand, B.; Didierjean, C.; Inguimbert, N. Bergofungin D, a Peptaibol Template for the Introduction of Chemical Modifications, Synthesis of Analogs and Comparative Studies of Their Structures. J. Pept. Sci. 2024, 30, e3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, D.; Mason, F.G.; Taylor, A. The Production of Alamethicins by Trichoderma spp. Can. J. Microbiol. 1987, 33, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Tezuka, Y.; Hatanaka, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Nishi, A.; Tubaki, K. Studies on Metabolites of Mycoparasitic Fungi. V. Ion-Spray Ionization Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Trichokonin-II, a Peptaibol Mixture Obtained from the Culture Broth of Trichoderma koningii. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Duclohier, H. Peptaibiotics and Peptaibols: An Alternative to Classical Antibiotics? Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duclohier, H. Antimicrobial Peptides and Peptaibols, Substitutes for Conventional Antibiotics. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2010, 16, 3212–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.-N.; Chen, Z.-H.; Song, X.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Shi, M.; Zhou, B.-C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Antimicrobial Peptide Trichokonin VI-Induced Alterations in the Morphological and Nanomechanical Properties of Bacillus subtilis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, M.Y.; Kong, F.; Feng, X.; Siegel, M.M.; Janso, J.E.; Graziani, E.I.; Carter, G.T. Septocylindrins A and B: Peptaibols Produced by the Terrestrial Fungus Septocylindrium sp. LL-Z1518. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruksakorn, P.; Arai, M.; Kotoku, N.; Vilchèze, C.; Baughn, A.D.; Moodley, P.; Jacobs, W.R.; Kobayashi, M. Trichoderins, Novel Aminolipopeptides from a Marine Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp., Are Active against Dormant Mycobacteria. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 3658–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruksakorn, P.; Arai, M.; Liu, L.; Moodley, P.; Jacobs, W.R., Jr.; Kobayashi, M. Action-Mechanism of Trichoderin A, an Anti-Dormant Mycobacterial Aminolipopeptide from Marine Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, I.; Ruiz, N.; Thomas, O.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Atanasova, L.; Tabbene, O.; Elkahoui, S.; Benzekri, R.; Bouslama, L.; Pouchus, Y.F.; et al. Hyporientalin A, an Anti-Candida Peptaibol from a Marine Trichoderma Orientale. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-L.; Liu, L.-J.; Shi, M.; Song, X.-Y.; Zheng, C.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Characterization and Gene Cloning of a Novel Serine Protease with Nematicidal Activity from Trichoderma pseudokoningii SMF2. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 299, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, D.-D.; Dong, X.-W.; Zhao, P.-B.; Chen, L.-L.; Song, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-J.; Chen, X.-L.; Shi, M.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Antimicrobial Peptaibols Induce Defense Responses and Systemic Resistance in Tobacco against Tobacco mosaic Virus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2010, 313, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, B.-S.; Yoo, I.-D.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, K.-S.; Yeo, W.-H. Peptaivirins A and B, Two New Antiviral Peptaibols against TMV Infection. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 1429–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, G.; Uma, M.V.; Shivayogi, M.S.; Balaram, H. Antiplasmodial Activity of Fungal Peptide Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, A.; Laub, A.; Wendt, L.; Porzel, A.; Schmidt, J.; Palfner, G.; Becerra, J.; Krüger, D.; Stadler, M.; Wessjohann, L.; et al. Chilenopeptins A and B, Peptaibols from the Chilean Sepedonium Aff. Chalcipori KSH 883. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degenkolb, T.; Fog Nielsen, K.; Dieckmann, R.; Branco-Rocha, F.; Chaverri, P.; Samuels, G.J.; Thrane, U.; von Döhren, H.; Vilcinskas, A.; Brückner, H. Peptaibol, Secondary-Metabolite, and Hydrophobin Pattern of Commercial Biocontrol Agents Formulated with Species of the Trichoderma harzianum Complex. Chem. Biodivers. 2015, 12, 662–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.-W.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, P.-B.; Song, X.-Y.; Sun, C.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Zhou, B.-C.; Zhang, Y.-Z. Antimicrobial Peptaibols from Trichoderma pseudokoningii Induce Programmed Cell Death in Plant Fungal Pathogens. Microbiology 2012, 158, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viterbo, A.; Wiest, A.; Brotman, Y.; Chet, I.; Kenerley, C. The 18mer Peptaibols from Trichoderma virens Elicit Plant Defence Responses. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béven, L.; Duval, D.; Rebuffat, S.; Riddell, F.G.; Bodo, B.; Wróblewski, H. Membrane Permeabilisation and Antimycoplasmic Activity of the 18-Residue Peptaibols, Trichorzins PA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 1998, 1372, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, I.; Chtaina, N.; El Kamli, T.; Grappin, P.; Guilli, M.E.; Ezzahiri, B. Bioactivity of Trichoderma harzianum A Peptaibols against Zymoseptoria tritici Causal Agent of Septoria Leaf Blotch of Wheat. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2023, 63, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, L.; Amiard, J.-C.; Mondeguer, F.; Quiniou, F.; Ruiz, N.; Pouchus, Y.F.; Montagu, M. Determination of Peptaibol Trace Amounts in Marine Sediments by Liquid Chromatography/Electrospray Ionization-Ion Trap-Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1160, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sallenave-Namont, C.; Pouchus, Y.F.; Robiou du Pont, T.; Lassus, P.; Verbist, J.F. Toxigenic Saprophytic Fungi in Marine Shellfish Farming Areas. Mycopathologia 2000, 149, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, L.; Montagu, M.; Landreau, A.; Mohamed-Benkada, M.; Grovel, O.; Sallenave-Namont, C.; Biard, J.; Amiard-Triquet, C.; Amiard, J.; Pouchus, Y.F. Peptaibols: Stable Markers of Fungal Development in the Marine Environment. Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiard-Triquet, O.C.; Geffard, A.; Geffard, H.; Budzinski, J.C.; Amiard, D.; Fichet, H.; Pouliquen, Y.; Berthelot, E. His. In Contaminated Sediments: Characterization, Evaluation, Mitigation/Restoration; Tremblay, J.H., Locat, R.G.-C., Eds.; Laval University: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2003; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- van Bohemen, A.-I.; Ruiz, N.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A.; Michaud, A.; Robiou du Pont, T.; Druzhinina, I.; Atanasova, L.; Prado, S.; Bodo, B.; Meslet-Cladiere, L.; et al. Pentadecaibins I–V: 15-Residue Peptaibols Produced by a Marine-Derived Trichoderma sp. of the Harzianum Clade. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbiato, L.; Quaggia, C.; Menilli, L.; Dalla Torre, C.; Barbon, A.; De Zotti, M. Synthesis, Conformational Analysis and Antitumor Activity of the Naturally Occurring Antimicrobial Medium-Length Peptaibol Pentadecaibin and Spin-Labeled Analogs Thereof. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Benkada, M.; Montagu, M.; Biard, J.; Mondeguer, F.; Verite, P.; Dalgalarrondo, M.; Bissett, J.; Pouchus, Y.F. New Short Peptaibols from a Marine Trichoderma Strain. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 20, 1176–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raap, J.; Erkelens, K.; Ogrel, A.; Skladnev, D.A.; Brückner, H. Fungal Biosynthesis of Non-ribosomal Peptide Antibiotics and α, α−dialkylated Amino Acid Constituents. J. Pept. Sci. 2005, 11, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otvos, L., Jr. Antibacterial Peptides Isolated from Insects. J. Pept. Sci. 2000, 6, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuffat, S.; Goulard, C.; Bodo, B. Antibiotic Peptides from Trichoderma harzianum: Harzianins HC, Proline-Rich 14-Residue Peptaibols. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1995, 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

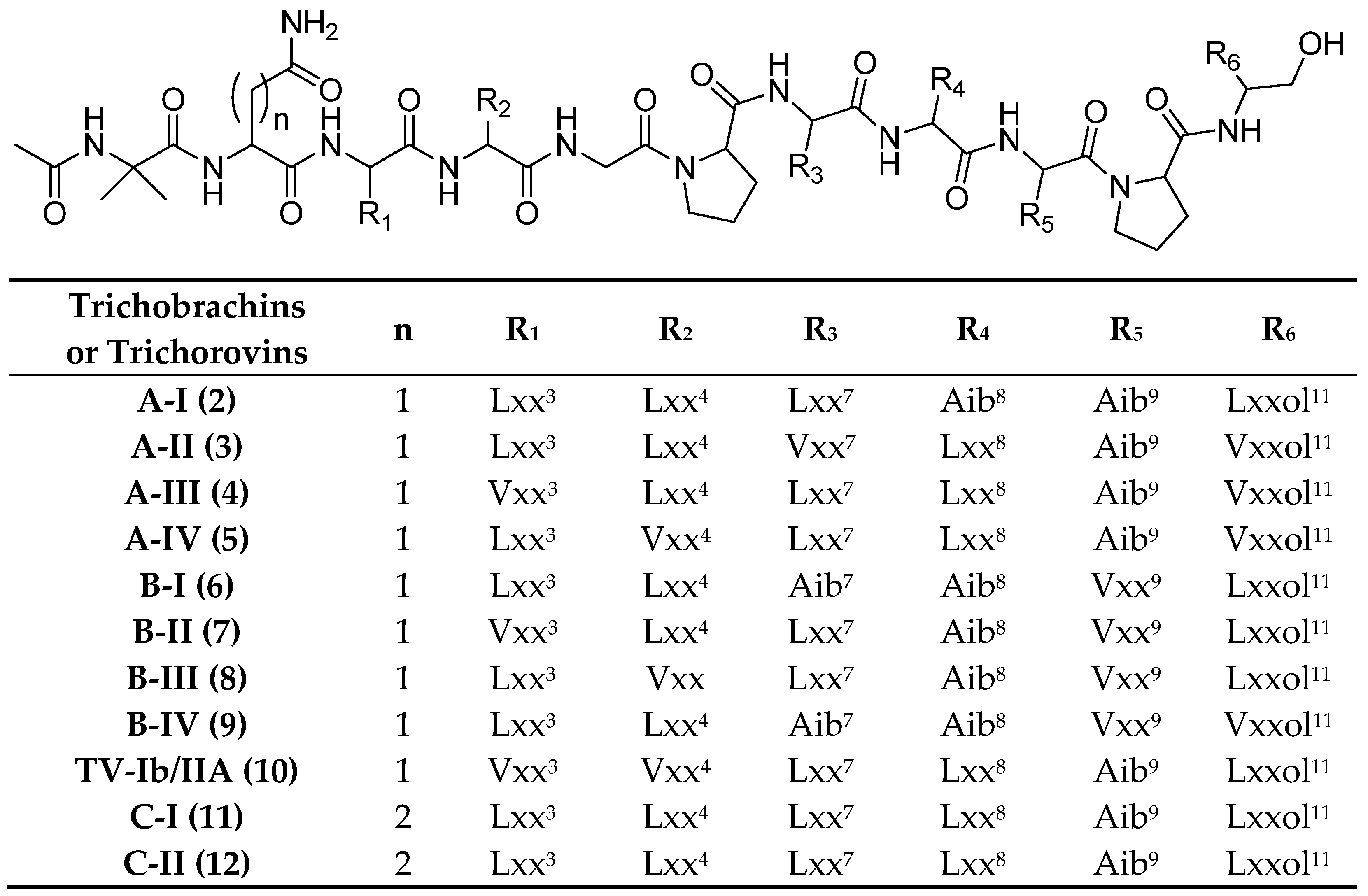

- Wada, S.; Iida, A.; Akimoto, N.; Kanai, M.; Toyama, N.; Fujita, T. Fungal Metabolites. XIX. Structural Elucidation of Channel-Forming Peptides, Trichorovins-I-XIV, from the Fungus Trichoderma viride. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 43, 910–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, N.; Wielgosz-Collin, G.; Poirier, L.; Grovel, O.; Petit, K.E.; Mohamed-Benkada, M.; du Pont, T.R.; Bissett, J.; Vérité, P.; Barnathan, G.; et al. New Trichobrachins, 11-Residue Peptaibols from a Marine Strain of Trichoderma longibrachiatum. Peptides 2007, 28, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirier, L.; Quiniou, F.; Ruiz, N.; Montagu, M.; Amiard, J.-C.; Pouchus, Y.F. Toxicity Assessment of Peptaibols and Contaminated Sediments on Crassostrea Gigas Embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2007, 83, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdarek, J.; Fraenkel, G. Pupariation in Flies: A Tool for Monitoring Effects of Drugs, Venoms, and Other Neurotoxic Compounds. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1987, 4, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

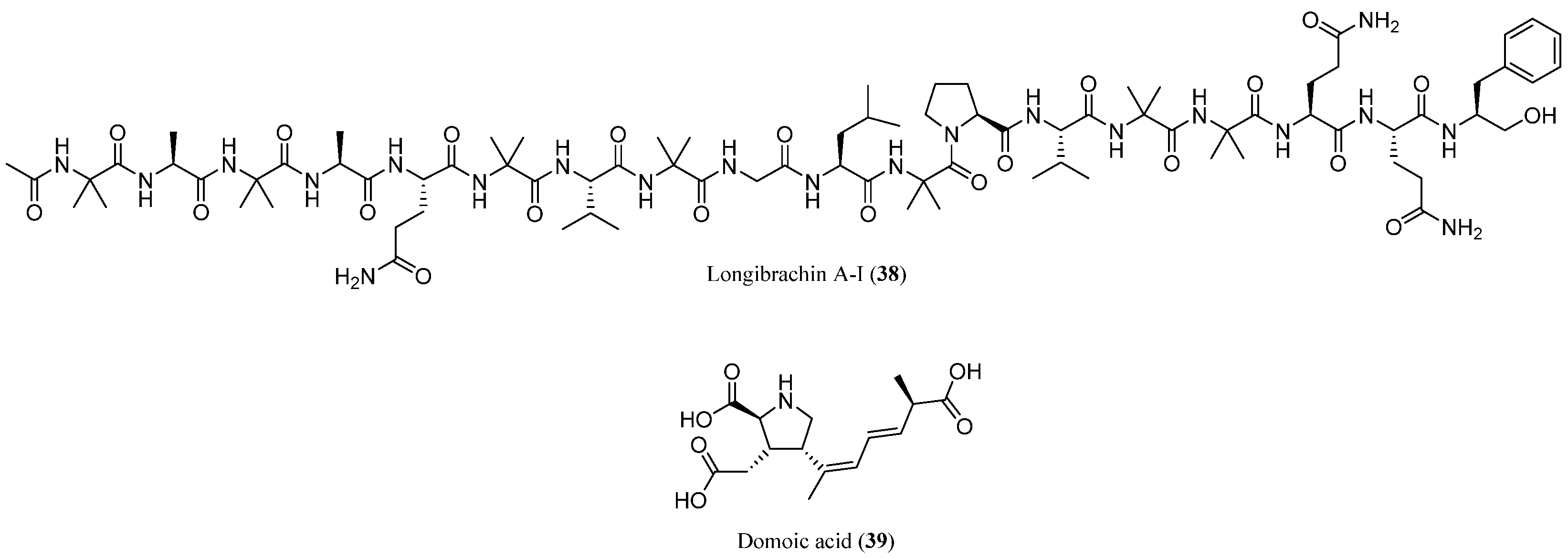

- Ruiz, N.; Petit, K.; Vansteelandt, M.; Kerzaon, I.; Baudet, J.; Amzil, Z.; Biard, J.-F.; Grovel, O.; Pouchus, Y.F. Enhancement of Domoic Acid Neurotoxicity on Diptera Larvae Bioassay by Marine Fungal Metabolites. Toxicon 2010, 55, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, H.; Przybylski, M. Methods for the Rapid Detection, Isolation and Sequence Determination of Peptaibols and Other Aib Containing Peptides of Fungal Origin. I. Gliodesquin A from Gliocladium deliquescens. Chromatographia 1984, 19, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Benkada, M.; François Pouchus, Y.; Vérité, P.; Pagniez, F.; Caroff, N.; Ruiz, N. Identification and Biological Activities of Long-Chain Peptaibols Produced by a Marine-Derived Strain of Trichoderma longibrachiatum. Chem. Biodivers. 2016, 13, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Xue, C.; Tian, L.; Xu, M.; Chen, J.; Deng, Z.; Proksch, P.; Lin, W. Asperelines A−F, Peptaibols from the Marine-Derived Fungus Trichoderma asperellum. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Zhong, P.; Pan, J.-R.; Zhou, K.-J.; Huang, K.; Fang, Z.-X. Asperelines G and H, Two New Peptaibols from the Marine-Derived Fungus Trichoderma asperellum. Heterocycles 2013, 87, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.R.P.; de Souza, A.Q.L.; dos Santos, L.A.; Nogueira, F.C.S.; Evaristo, J.A.M.; Carneiro, G.R.A.; da Silva, G.F.; da Cruz, J.C.; Sousa, T.F.; da Silva, S.R.S.; et al. Asperelines Produced by the Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma asperelloides from the Aquatic Plant Victoria amazonica. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2021, 31, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenkolb, T.; Gräfenhan, T.; Berg, A.; Nirenberg, H.I.; Gams, W.; Brückner, H. Peptaibiomics: Screening for Polypeptide Antibiotics (Peptaibiotics) from Plant-Protective Trichoderma Species. Chem. Biodivers. 2006, 3, 593–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizel, I.; Yarden, O.; Ilan, M.; Carmeli, S. Eight New Peptaibols from Sponge-Associated Trichoderma atroviride. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 4937–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrich, C.R.; Iversen, A.; Jaklitsch, W.M.; Voglmayr, H.; Vilcinskas, A.; Nielsen, K.F.; Thrane, U.; von Döhren, H.; Brückner, H.; Degenkolb, T. Screening the Biosphere: The Fungicolous Fungus Trichoderma Phellinicola, a Prolific Source of Hypophellins, New 17-, 18-, 19-, and 20-Residue Peptaibiotics. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaklitsch, W.M.; Voglmayr, H. New Combinations in Trichoderma (Hypocreaceae, Hypocreales). Mycotaxon 2013, 126, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, G.; Rebuffat, S.; Goulard, C.; Bodo, B. Directed Biosynthesis of Peptaibol Antibiotics in Two Trichoderma Strains. I. Fermentation and Isolation. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.; Kirschbaum, J.; Jung, G.; Brückner, H. Sequence Diversity of the Peptaibol Antibiotic Suzukacillin-A from the Mold Trichoderma viride. J. Pept. Sci. 2006, 12, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, C.; Kirschbaum, J.; Brückner, H. Peptaibiomics: Microheterogeneity, Dynamics, and Sequences of Trichobrachins, Peptaibiotics from Trichoderma Parceramosum Bissett (T. longibrachiatum Rifai). Chem. Biodivers. 2007, 4, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbene, O.; Kalai, L.; Ben Slimene, I.; Karkouch, I.; Elkahoui, S.; Gharbi, A.; Cosette, P.; Mangoni, M.-L.; Jouenne, T.; Limam, F. Anti-Candida Effect of Bacillomycin D-like Lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis B38. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 316, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, J.K.; Brückner, H.; Wallace, B.A. Model for a Helical Bundle Channel Based on the High-Resolution Crystal Structure of Trichotoxin_A50E. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 12934–12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredics, L.; Szekeres, A.; Czifra, D.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Leitgeb, B. Recent Results in Alamethicin Research. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 744–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Tang, Z.; Gan, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, X.; Gao, C.; Zhao, L.; Chai, L.; Liu, Y. 18-Residue Peptaibols Produced by the Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp. GXIMD 01001. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Tang, Z.; Luo, X.; Gan, Y.; Bai, M.; Lin, H.; Gao, C.; Chai, L.; Lin, X. Lipotrichaibol A and Trichoderpeptides A–D: Five New Peptaibiotics from a Sponge-Derived Trichoderma sp. GXIMD 01001. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.P.; Yedukondalu, N.; Sharma, V.; Kushwaha, M.; Sharma, R.; Chaubey, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Lipovelutibols A–D: Cytotoxic Lipopeptaibols from the Himalayan Cold Habitat Fungus Trichoderma velutinum. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inostroza, A.; Lara, L.; Paz, C.; Perez, A.; Galleguillos, F.; Hernandez, V.; Becerra, J.; González-Rocha, G.; Silva, M. Antibiotic Activity of Emerimicin IV Isolated from Emericellopsis Minima from Talcahuano Bay, Chile. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuvarina, A.E.; Gavryushina, I.A.; Sykonnikov, M.A.; Efimenko, T.A.; Markelova, N.N.; Bilanenko, E.N.; Bondarenko, S.A.; Kokaeva, L.Y.; Timofeeva, A.V.; Serebryakova, M.V.; et al. Exploring Peptaibol’s Profile, Antifungal, and Antitumor Activity of Emericellipsin A of Emericellopsis Species from Soda and Saline Soils. Molecules 2022, 27, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvarina, A.E.; Gavryushina, I.A.; Kulko, A.B.; Ivanov, I.A.; Rogozhin, E.A.; Georgieva, M.L.; Sadykova, V.S. The Emericellipsins A–E from an Alkalophilic Fungus Emericellopsis Alkalina Show Potent Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Pathogenic Fungi. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boot, C.M.; Tenney, K.; Valeriote, F.A.; Crews, P. Highly N-Methylated Linear Peptides Produced by an Atypical Sponge-Derived Acremonium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Krasnoff, S.B.; Roberts, D.W.; Renvich, J.A.A.; Brinen, L.S.; Clardy, J. Structure of Efrapeptins from the Fungus Tolypocladium niveum. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnoff, S.B.; Gupta, S.; St Leger, R.J.; Renwick, J.A.A.; Roberts, D.W. Antifungal and Insecticidal Properties of the Efrapeptins: Metabolites of the Fungus Tolypocladium niveum. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1991, 58, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnoff, S.B.; Gupta, S. Identification and Directed Biosynthesis of Efrapeptins in the Fungus Tolypocladium Geodes Gams (Deuteromycotina: Hyphomycetes). J. Chem. Ecol. 1991, 17, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, S.J.; Grüschow, S.; Williams, D.H.; McNicholas, C.; Purewal, R.; Hajek, M.; Gerlitz, M.; Martin, S.; Wrigley, S.K.; Moore, M. Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Chlorofusin, a Novel P53-MDM2 Antagonist from a Fusarium sp. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvin-Guette, C.; Rebuffat, S.; Vuidepot, I.; Massias, M.; Bodo, B. Structural Elucidation of Trikoningins KA and KB, Peptaibols from Trichoderma koningii. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1993, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Herath, K.; Guan, Z.Q.; Zink, D.L.; Dombrowski, A.W.; Polishook, J.D.; Silverman, D.C.; Lingham, R.B.; Felock, P.J.; Hazuda, D.J. Integramides A and B, Two Novel Non-ribosomal Linear Peptides Containing Nine C(alpha)-methyl Amino Acids Produced by Fungal Fermentations that Are Inhibitors of HIV-1 Integrase. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Li, S.; Ni, J.; Wang, G.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Shu, J.; Gan, M. Acremopeptaibols A–F, 16-Residue Peptaibols from the Sponge-Derived Acremonium sp. IMB18-086 Cultivated with Heat-Killed Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2990–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

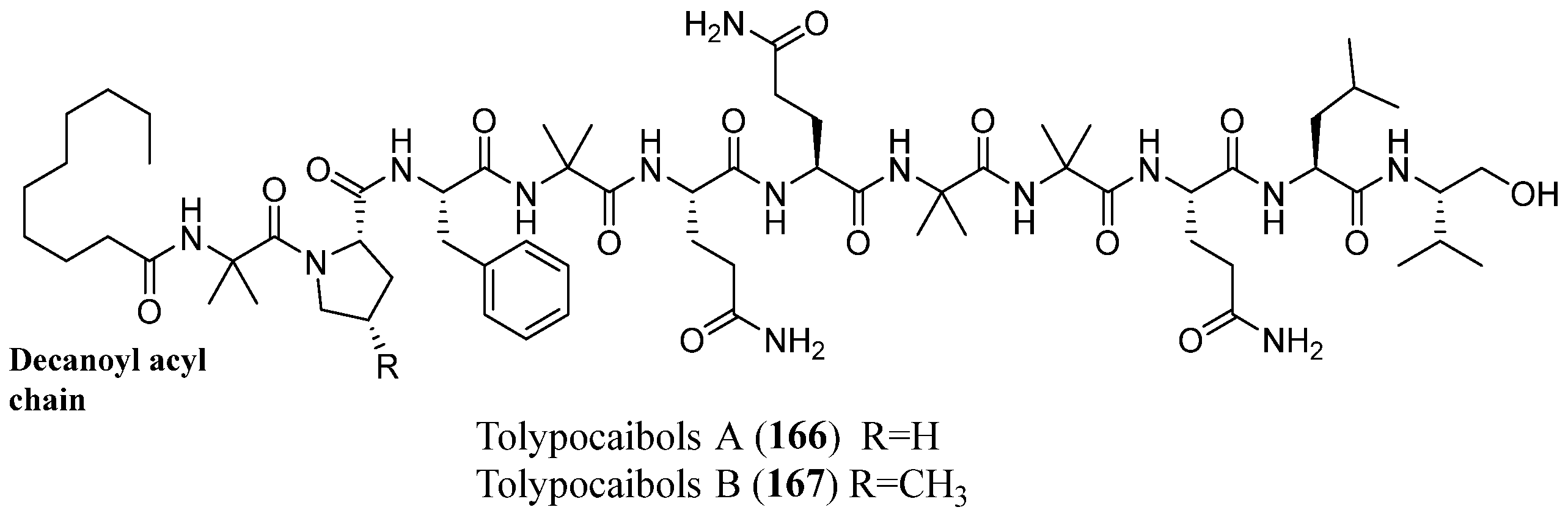

- Morehouse, N.J.; Flewelling, A.J.; Liu, D.Y.; Cavanagh, H.; Linington, R.G.; Johnson, J.A.; Gray, C.A. Tolypocaibols: Antibacterial Lipopeptaibols from a Tolypocladium sp. Endophyte of the Marine Macroalga Spongomorpha Arcta. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

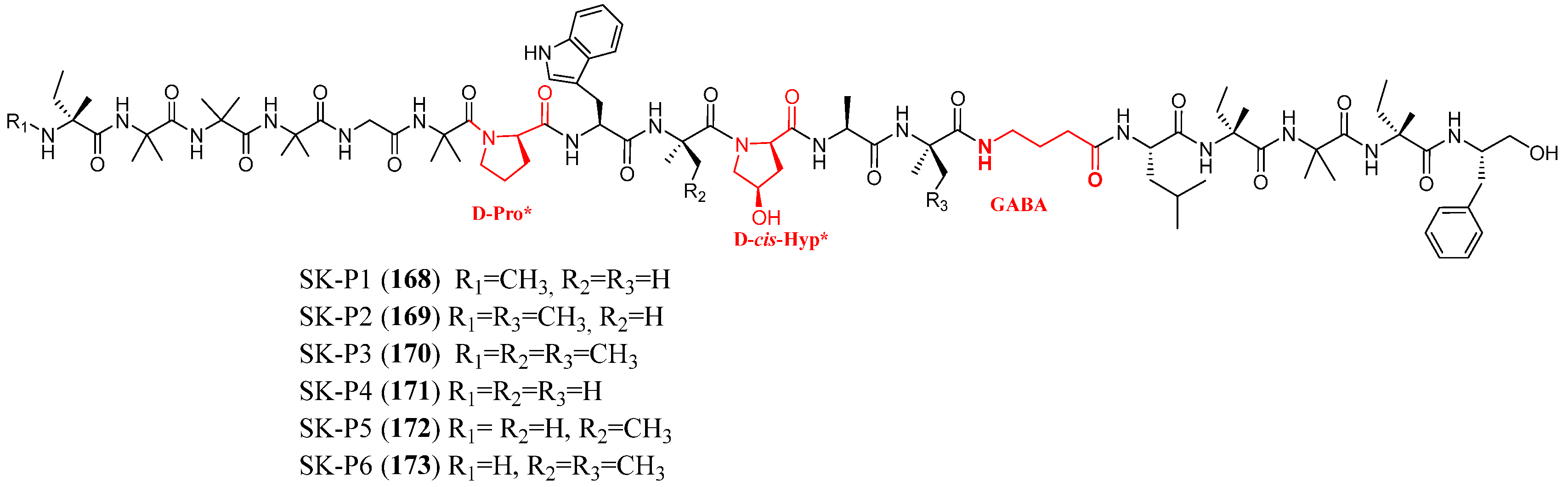

- Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Wang, L.; Fan, A.; Wu, M.; Xu, N.; Zhu, K.; Lin, W. Marine-Derived New Peptaibols with Antibacterial Activities by Targeting Bacterial Membrane Phospholipids. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 2764–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trichobrachins | Sequence |

|---|---|

| A-VIa (13) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Vxx3-Vxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Vxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Vxxol11 |

| A-VIb (14) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Vxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Vxx7-Vxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Vxxol11 |

| A-VIc (15) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Vxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Vxx7-Vxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Vxxol11 |

| A-VId (16) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Vxx3-Vxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Vxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Vxxol11 |

| A-VIe (17) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Vxx3-Vxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Vxx7-Vxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Lxxol11 |

| A-VIIa (18) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIb (19) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIc (20) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIId (21) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIe (22) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIf (23) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIg (24) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIh (25) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIi (26) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIj (27) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-IVa (28) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-IVb (29) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-IVc (30) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-IVd (31) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIIa (32) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Valol11 |

| A-VIIIb (33) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Val4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIIc (34) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Val3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIId (35) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Val8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-VIIIe (36) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Val7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| A-IX (37) | Ac-Aib1-Asn2-Lxx3-Lxx4-Aib5-Pro6-Lxx7-Lxx8-Aib9-Pro10-Leuol11 |

| Longibrachins | Sequence |

|---|---|

| A-0 (40) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Aib3-Ala4-Aib5-Ala6-Gln7-Aib8-Vxx9-Aib10-Gly11-Vxx12-Aib13-Pro14-Vxx15-Aib16-Aib17-Gln18-Gln19-Pheol20 |

| A-II-a (41) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Aib3-Ala4-Aib5-Ala6-Gln7-Aib8-Vxx9-Aib10-Gly11-Lxx12-Aib13-Pro14-Vxx15-Aib16-Vxx17-Gln18-Gln19-Pheol20 |

| A-IV-b (42) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Aib3-Ala4-Aib5-Aib6-Gln7-Aib8-Vxx9-Aib10-Gly11-Lxx12-Aib13-Pro14-Vxx15-Aib16-Vxx17-Gln18-Gln19-Pheol20 |

| Asperelines | Sequence |

|---|---|

| I (51) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| J (52) | Ac-Ala1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Ala7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| K (53) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Ala7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| L (54) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Ala3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| M (55) | Ac-Ala1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| N (56) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Prolinol10 |

| O (57) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Ala7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| P (58) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Ala4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Q (59) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Ala6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| R (60) | Ac-Ala1-Val2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Ala6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| S (61) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Ala9-Pro-ol10 |

| T (62) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Ala9-Pro-ol10 |

| U (63) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| W (64) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| X (65) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Ala4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Y (66) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Ala7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z (67) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Ala6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z1 (68) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Ala7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z2 (69) | Ac-Aib1-Val2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Ala9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z3 (70) | Ac-Ala1-Val2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z4 (71) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z5 (72) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Ser7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z6 (73) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Ala6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z7 (74) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Ala7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z8 (75) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z9 (76) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z10 (77) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-SerVal6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z11 (78) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z12 (79) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Hyp-ol10 |

| Z13 (80) | Ac-Aib1-Val2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Asperelines | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Z14 (81) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Gly8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z15 (82) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Gly8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z16 (83) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Gly8-Aib9-Pro-ol10 |

| Z17 (84) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Gly8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z18 (85) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z19 (86) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z20 (87) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ala8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z21 (88) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Val3-Aib4-Lxx5-Aib6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Z22 (89) | Ac-Aib1-Aib2-Val3-Aib4-Val5-Aib6-Aib7-Ser8-Aib9-Pro10 |

| Trichorzianines (TA) | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TA-17A-I a (90) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-I b (91) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Ala5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-I c (92) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-I d (93) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Vxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-I e (94) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Vxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II a (95) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II b (96) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II c (97) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II d (98) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II e (99) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-II f (100) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Vxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-III a (101) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-III b (102) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-III c (103) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-III d (104) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17A-IV a (105) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I a (106) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I b (107) | Ac-Ala1-Aib2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I c (108) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I d (109) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I e (110) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Vxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-I f (111) | Ac-Ala1-Aib2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Vxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-II a (112) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-II b (113) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-II c (114) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-II d (115) | Ac-Ala1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-III a (116) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-III b (117) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Aib3-Ala4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| TA-17S-III c (118) | Ac-Ala1-Aib2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-[C129]17 |

| Trichorzianines (TA) | Sequence |

|---|---|

| TA-19A-I a (119) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-Gln17-Gln18-Pheol19 |

| TA-19A-II a (120) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Vxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-Gln17-Gln18- Pheol19 |

| TA-19A-III a (121) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Vxx5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ala10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-Gln17-Gln18- Pheol19 |

| TA-19 S-I aa) (122) | Ac-Aib1-Ala2-Ala3-Aib4-Aib5-Gln6-Aib7-Aib8-Aib9-Ser10-Lxx11-Aib12-Pro13-Lxx14-Aib15-Lxx16-Gln17-Gln18- Pheol19 |

| Name of Compound | N. | Isolated from | Marine-Derived Fungi | Biological Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trichobrachin A-I-IV | 2–5 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin B-I-IV | 6–9 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin TV-Ib/IIA | 10 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin C I-II | 11–12 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin A-VI a–e | 13–17 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin A-VII a–j | 18–27 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin A-IV a–d | 28–31 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin A-VIII a–e | 32–36 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Trichobrachin A-IX | 37 | T. longibrachiatum | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic | [68] |

| Longibrachin A-I | 38 | T. longibrachiatum (T. koningii) | Several sources | Antimicrobial, cytotoxic, genotoxic | [68] |

| Longibrachin A-0 | 40 | T. longibrachiatum (MMS151) | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic, antibacterial, antifungal | [73] |

| Longibrachin A-II-a | 41 | T. longibrachiatum (MMS151) | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic, antibacterial, antifungal | [73] |

| Longibrachin A-IV-b | 42 | T. longibrachiatum (MMS151) | Mytilus edulis | Cytotoxic, antibacterial, antifungal | [73] |

| Asperelines A-F | 43–48 | T. longibrachiatum T. asperellum (Y19-07) | Soil | Antimicrobial | [78] |

| Aspereline G | 49 | T. asperellum | Marine sediments | Cytotoxicity | [24,75] |

| Aspereline H | 50 | T. asperellum | Marine sediments | Cytotoxicity | [24,75] |

| Asperelines I-Z | 51–67 | T. asperellum | Marine sediments | Cytotoxicity | [24] |

| Asperelines Z1–Z13 | 68–80 | T. asperellum | Marine sediments | Cytotoxicity | [24] |

| Asperelines Z14–Z22 | 81–89 | T. asperelloides | Victoria amazonica | Antimicrobial | [76] |

| Trichorzianine 17A I a–e | 90–94 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17A II a–f | 95–100 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17A III a–d | 101–104 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17A IV a | 105 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17S I a–f | 106–111 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17S II a–d | 112–115 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 17S III a–c | 116–118 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 19A I a | 119 | T. atroviride MMS927 | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 19A II a | 120 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 19A III a | 121 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

| Trichorzianine 19S I a | 122 | T. atroviride (MMS927) | Shellfish | Cytotoxic | [25] |

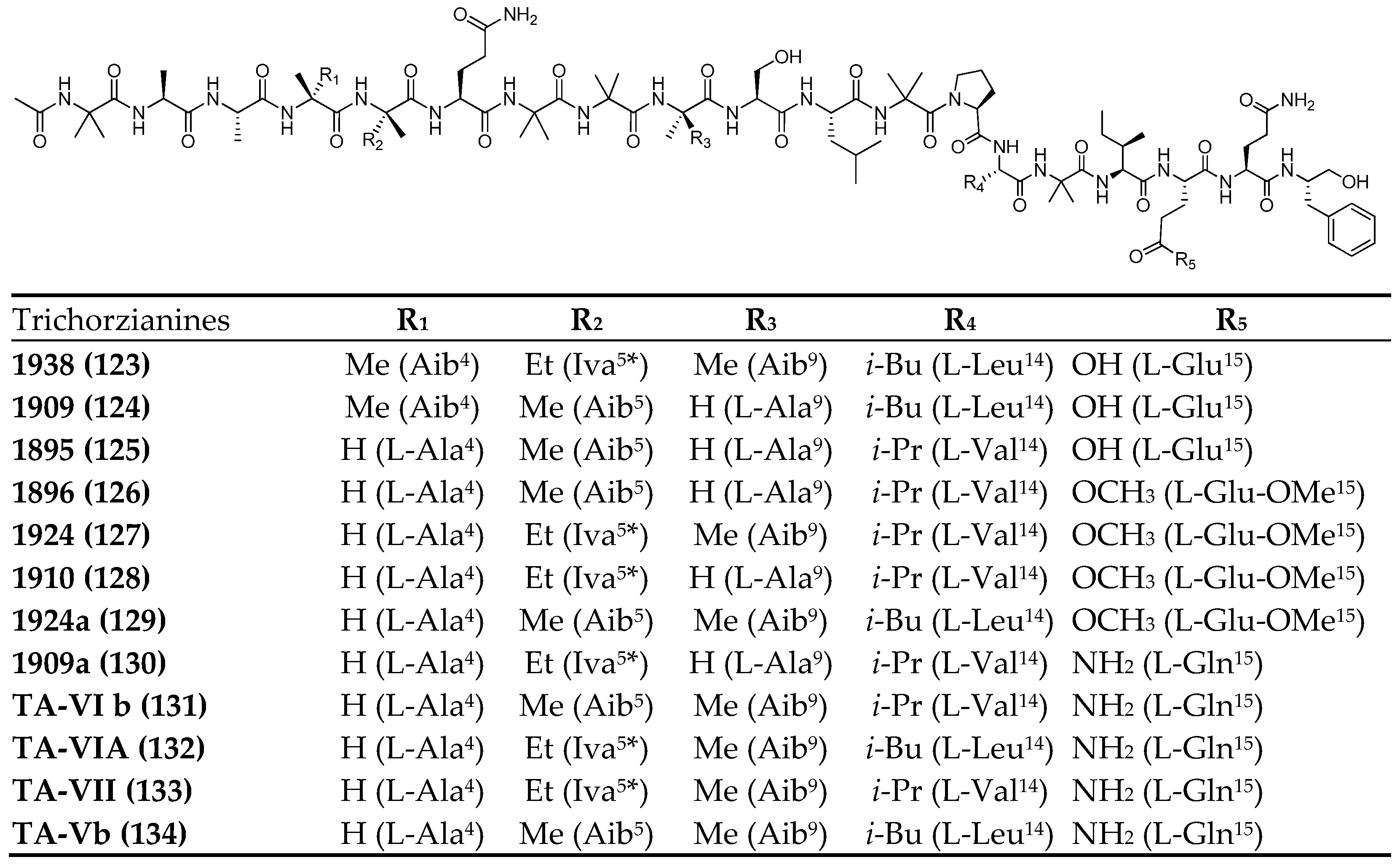

| Trichorzianine 1938 | 123 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1909 | 124 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1895 | 125 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1896 | 126 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1924 | 127 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1910 | 128 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1924a | 129 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine 1909a | 130 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine TA-VI b | 131 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine TA-VI A | 132 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Trichorzianine TA-VII | 133 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | - | [77] |

| Trichorzianine TA-V b | 134 | T. atroviride (NF16) | Sponge | Antimicrobial | [77] |

| Hyporientalin A | 135 | T.orientale | Cymbaxinella damicornis | Antibacterial, antifungal | [79] |

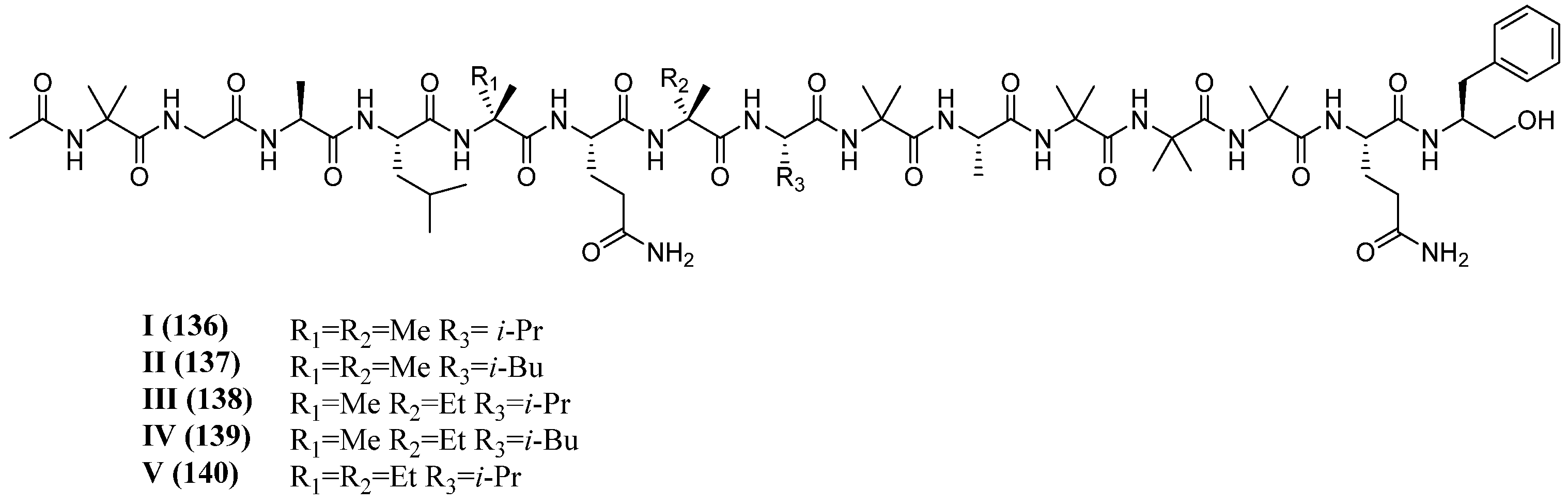

| Pentadecaibins I–V | 136–140 | T. harzianum (MMS1255) | Sediment | Antimicrobial, cytotoxic | [61] |

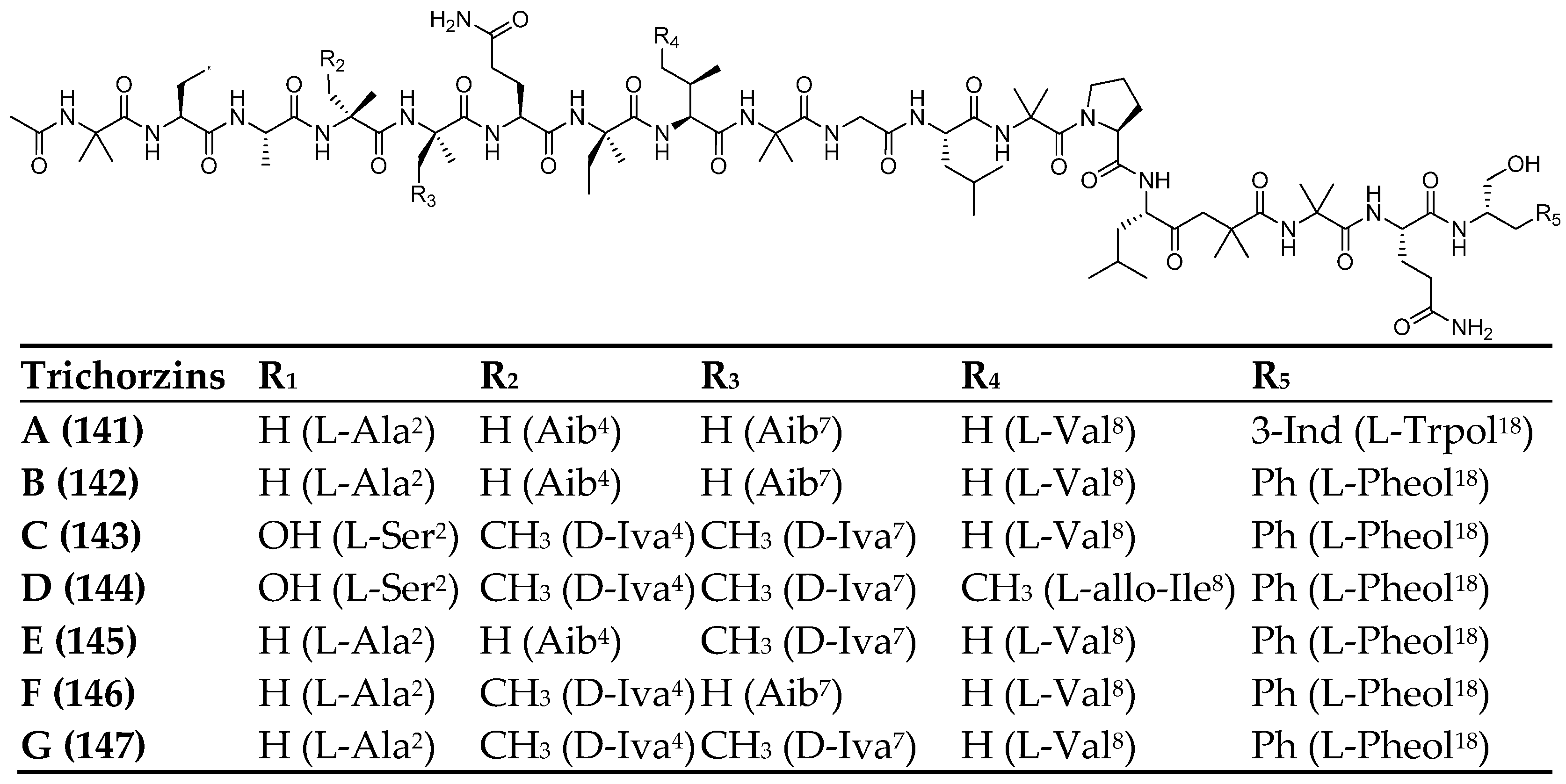

| Trichorzins A–G | 141–147 | Trichoderma sp. (GXIMD 01001) | Haliclona sp | Cytotoxic | [86] |

| Lipotrichaibol A | 148 | Trichoderma sp. (GXIMD 01001) | Sponge | Antiproliferative, cytotoxic | [88] |

| Trichoderpeptides A–D | 149–152 | Trichoderma sp. (GXIMD 01001) | Sponge | - | [88] |

| Emerimicin IV | 153 | Emericellopsis minima | Sediment | Bacteriostatic | [89] |

| Emericellipsin A | 154 | Emericellopsis alkalina | Several sources | Cytotoxic | [90] |

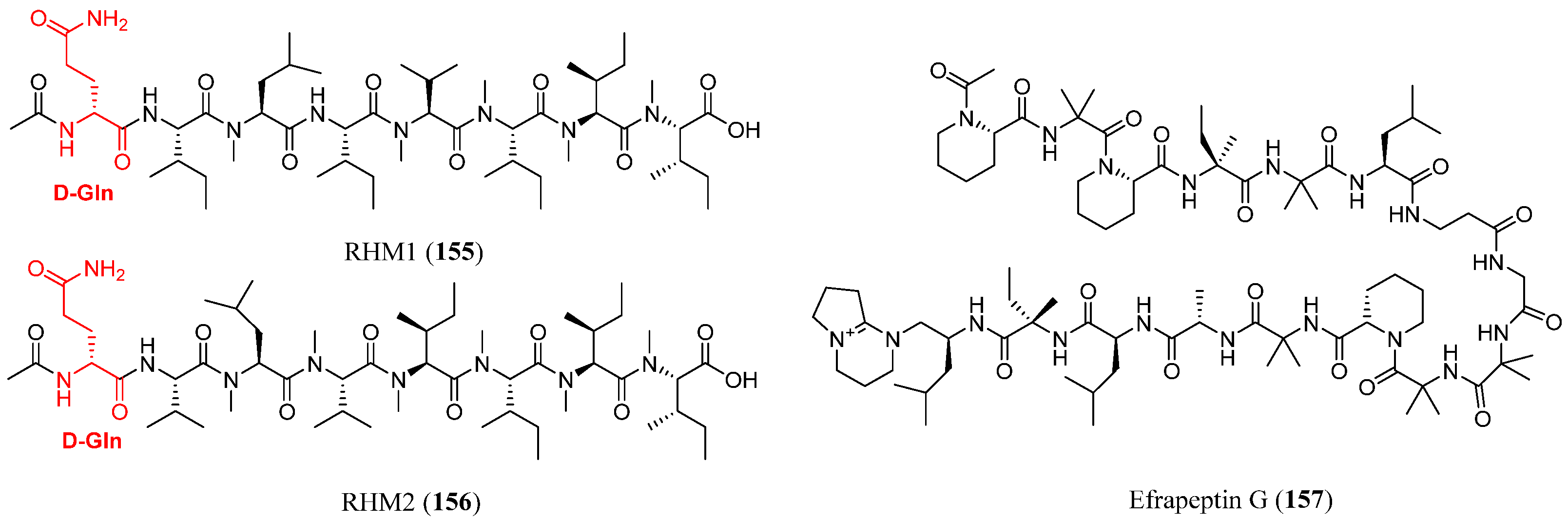

| RHM1 | 155 | Acremonium sp. (021172cKZ) | Teichaxinella sp. | Cytotoxic, antibacterial | [92] |

| RHM2 | 156 | Acremonium sp. (021172cKZ) | Teichaxinella sp. | Cytotoxic | [92] |

| Efrapeptin G | 157 | Acremonium sp. (021172cKZ) | Teichaxinella sp. | Cytotoxic | [92,94] |

| Acremopeptaibols A–F | 158–163 | Acremonium sp. (IMB18-086) | Haliclona sp. | Antimicrobial, antifungal | [100] |

| Microbacterins A–B | 164–165 | Microbacterium sediminis spp. YLB-01-T | Sediment | Cytotoxic | [29] |

| Tolypocaibols A–B | 166–167 | Tolypocladium sp. (KP1-175E) | Spongomorpha arcta | Antibacterial | [101] |

| SK-P1–SK-P6 | 168–173 | Stephanonectria keithii (LZD-10-1) | Peseudopterogorgia sp. LZD-10 | Antibacterial | [102] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Finamore, C.; Festa, C.; Cammarota, M.; De Marino, S.; D’Auria, M.V. A Journey into the Blue: Current Knowledge and Emerging Insights into Marine-Derived Peptaibols. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120458

Finamore C, Festa C, Cammarota M, De Marino S, D’Auria MV. A Journey into the Blue: Current Knowledge and Emerging Insights into Marine-Derived Peptaibols. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):458. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120458

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinamore, Claudia, Carmen Festa, Mattia Cammarota, Simona De Marino, and Maria Valeria D’Auria. 2025. "A Journey into the Blue: Current Knowledge and Emerging Insights into Marine-Derived Peptaibols" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120458

APA StyleFinamore, C., Festa, C., Cammarota, M., De Marino, S., & D’Auria, M. V. (2025). A Journey into the Blue: Current Knowledge and Emerging Insights into Marine-Derived Peptaibols. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120458