Enhanced Toxicity of Diol-Estered Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins Across Trophic Levels: Evidence from Caenorhabditis elegans and Mytilus galloprovincialis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

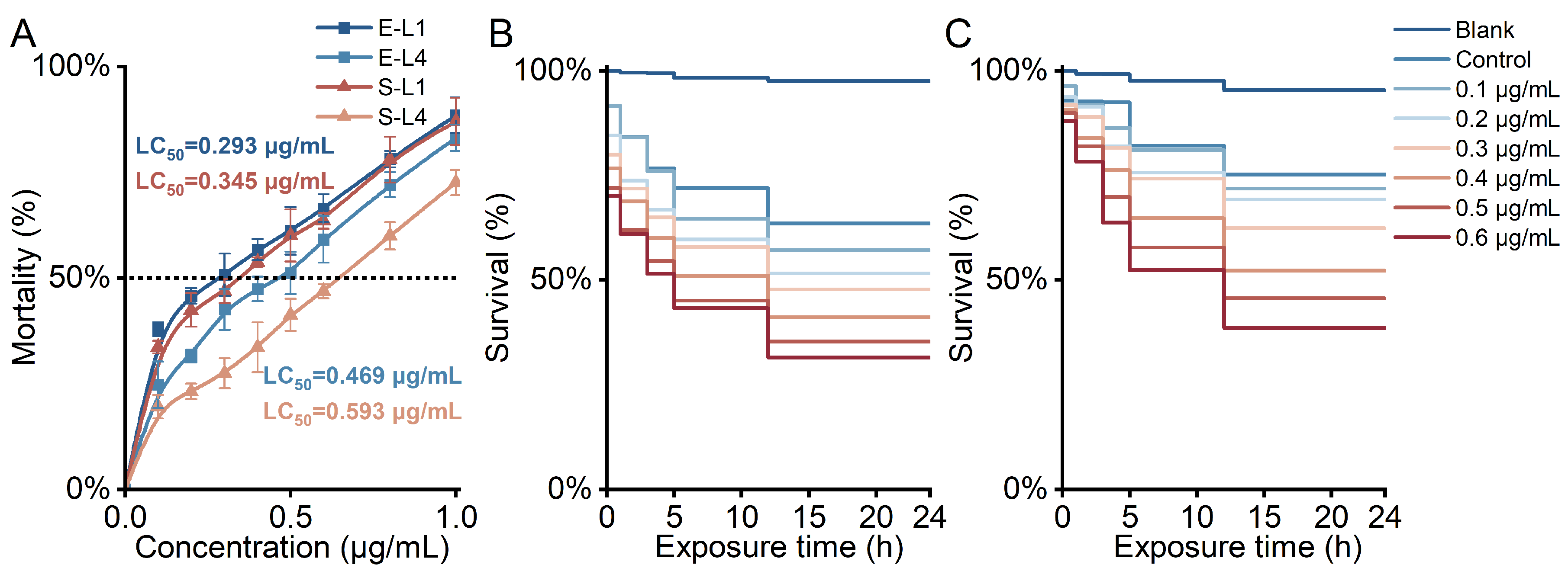

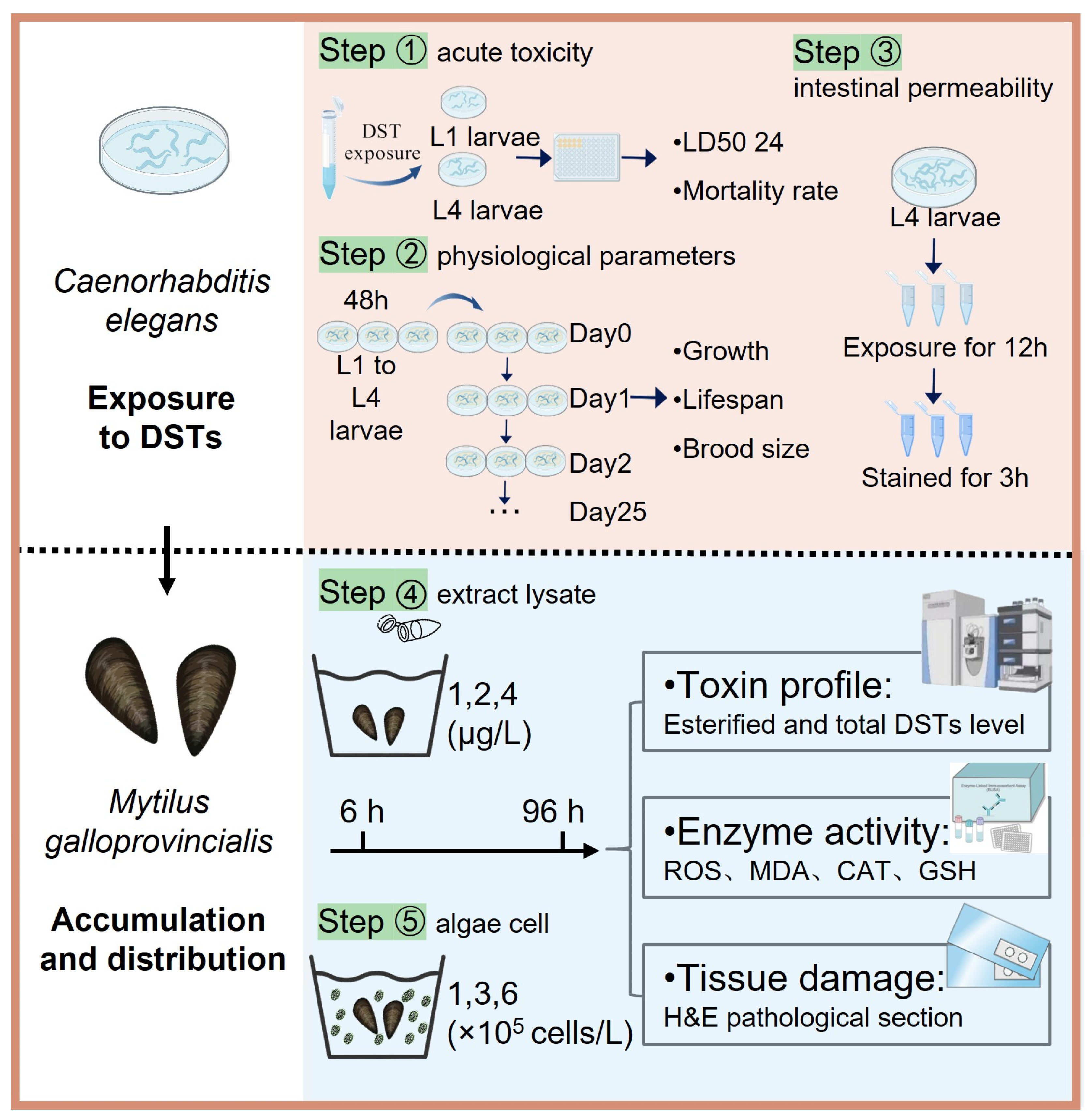

2.1. Acute Toxicity of DSTs to C. elegans

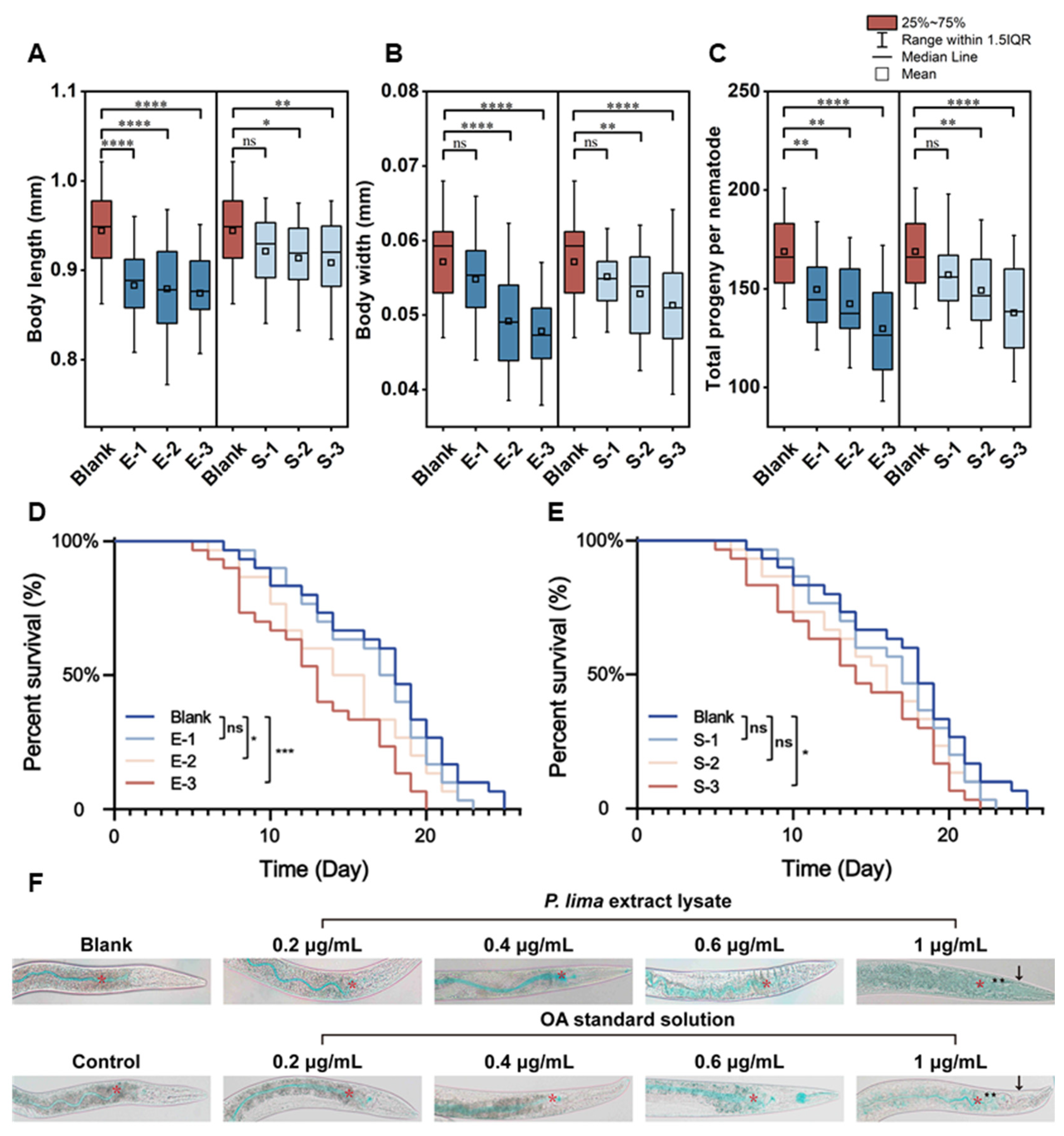

2.2. Effect of DSTs on Physiological Parameters in C. elegans

2.3. Effect of DSTs on Intestinal Permeability in C. elegans

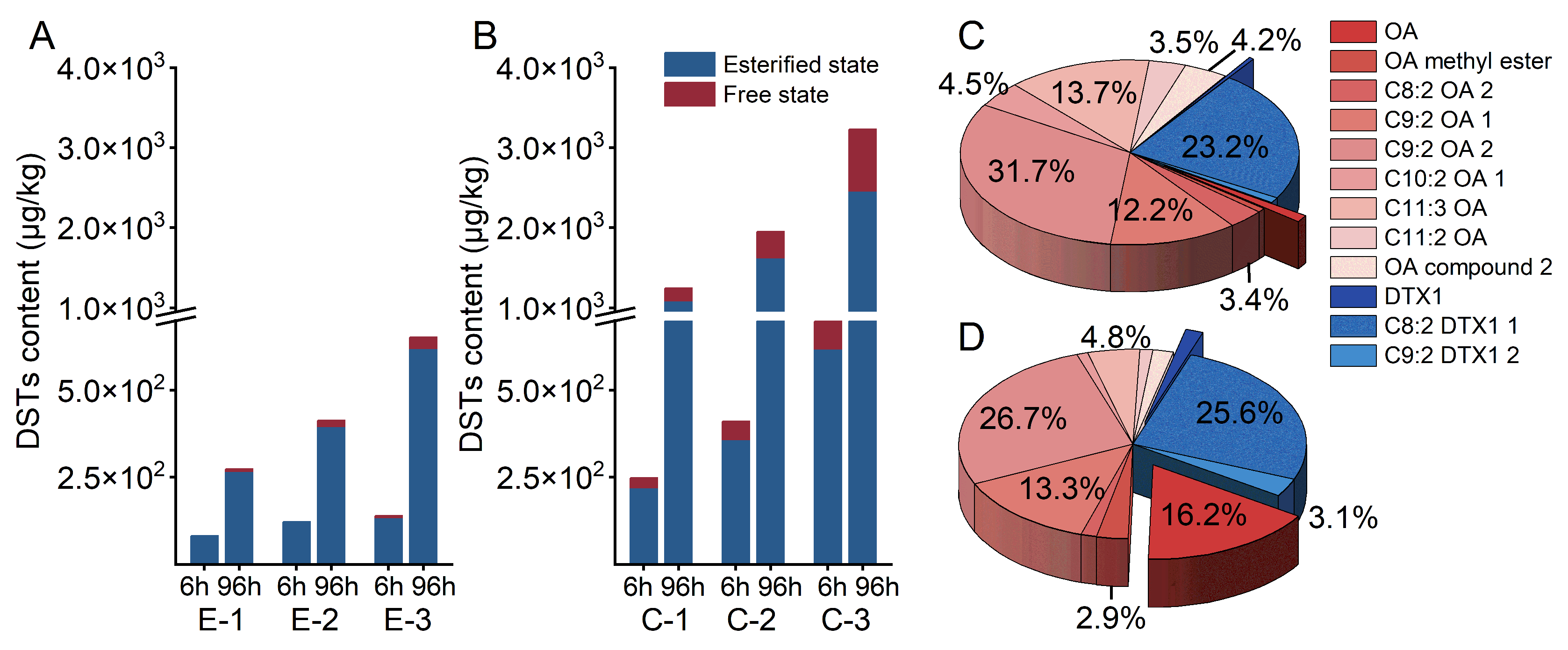

2.4. Accumulation and Distribution of DSTs in Mussels

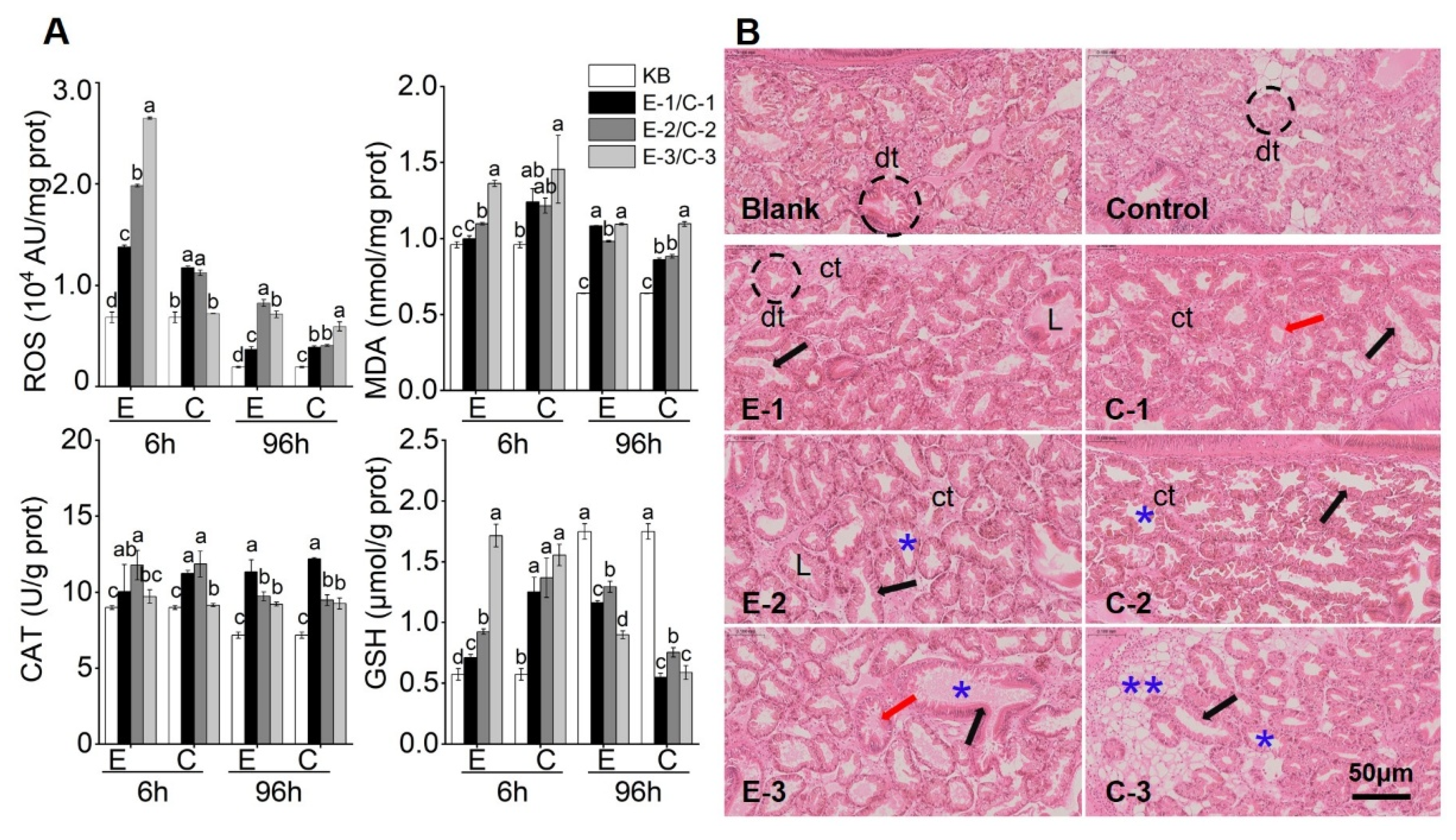

2.5. Effects of DSTs on Oxidative Activity Damage in Mussels

3. Discussion

3.1. Acute Toxicity and Difference Assessment

3.2. Bioaccumulation and Ecological Risk

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

4.2. Material Preparation

4.2.1. Animals

4.2.2. Algal Cell Culture and Extraction Lysate Preparation

4.3. Toxicity Assessment of DSTs to C. elegans

4.3.1. Synchronization

4.3.2. Acute Toxicity

4.3.3. Physiological Parameters

4.3.4. Intestinal Permeability

4.4. Toxicity and Accumulation of DSTs in Mytilus galloprovincialis

4.4.1. Exposure Experiment

4.4.2. Toxin Extraction

4.4.3. Analysis of DSTs by LC-HRMS/MS

4.4.4. Analysis of Oxidation Activity

4.5. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolny, J.L.; Tomlinson, M.C.; Schollaert Uz, S.; Egerton, T.A.; McKay, J.R.; Meredith, A.; Reece, K.S.; Scott, G.P.; Stumpf, R.P. Current and Future Remote Sensing of Harmful Algal Blooms in the Chesapeake Bay to Support the Shellfish Industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Zhong, Y.; Zheng, G.; Guo, M.; Tan, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Lu, S. Nontarget screening and toxicity evaluation of diol esters of okadaic acid and dinophysistoxins reveal intraspecies difference of Prorocentrum lima. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 12366–12375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Fensin, E.; Gobler, C.J.; Hoeglund, A.E.; Hubbard, K.A.; Kulis, D.M.; Landsberg, J.H.; Lefebvre, K.A.; Provoost, P.; Richlen, M.L.; et al. Marine harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the United States: History, current status and future trends. Harmful Algae 2021, 102, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Peng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, G.; Tan, Z.; Wu, H. The toxin-producing diversity of Prorocentrum lima (Dinophyceae) populations of coastal China. Harmful Algae 2025, 148, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Reference Laboratory For Marine Biotoxins (EURLMB). EU-Harmonised Standard Operating Procedure for Determination of Lipophilic Marine Biotoxins in Molluscs by LC-MS/MS; AECOSAN: Vigo, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, L.; Chen, J.; Shen, H.; He, X.; Li, G.; Song, X.; Zhou, D.; Sun, C. Profiling of extracellular toxins associated with diarrhetic shellfish poison in Prorocentrum lima culture medium by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. Toxins 2017, 9, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, M.; Jiao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, W. De novo transcriptome analysis of the mussel Perna viridis after exposure to the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Ecotox. Environ. Safe 2020, 192, 110265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Geng, N.; Wu, M.; Yi, X.; Liu, R.; Challis, J.K.; Codling, G.; Xu, E.G.; Giesy, J.P. Molecular mechanisms of zooplanktonic toxicity in the okadaic acid-producing dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Fleming, L.E.; Gowen, R.; Davidson, K.; Hess, P.; Backer, L.C.; Moore, S.K.; Hoagland, P.; Enevoldsen, H. Marine harmful algal blooms, human health and wellbeing: Challenges and opportunities in the 21st century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2016, 96, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Peng, J.; Zheng, G.; Lu, S.; Tan, Z. Adaptive responses of geographically distinct strains of the benthic dinoflagellate, Prorocentrum lima (Dinophyceae), to varying light intensity and photoperiod. Harmful Algae 2023, 127, 102479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, H.; Zheng, G.; Zhong, Y.; Tan, Z. Variation profile of diarrhetic shellfish toxins and diol esters derivatives of Prorocentrum lima during growth by high-resolution mass spectrometry. Toxicon 2023, 232, 107224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ruan, Y.; Mak, Y.L.; Zhang, X.; Lam, J.C.W.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lam, P.K.S. Occurrence and Trophodynamics of Marine Lipophilic Phycotoxins in a Subtropical Marine Food Web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 8829–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdalet, E.; Kudela, R.; Urban, E.; Enevoldsen, H.; Banas, N.S.; Bresnan, E.; Burford, M.; Davidson, K.; Gobler, C.J.; Karlson, B.; et al. GlobalHAB: A New Program to Promote International Research, Observations, and Modeling of Harmful Algal Blooms in Aquatic Systems. Oceanography 2021, 30, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganuma, M.; Fujiki, H.; Okabe, S.; Nishiwaki, S.; Brautigan, D.; Ingebritsen, T.S.; Rosner, M.R. Structurally different members of the okadaic acid class selectively inhibit protein serine/threonine but not tyrosine phosphatase activity. Toxicon 1992, 30, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Faraldo, M.; Valdiglesias, V.; Laffon, B.; Mendez, J.; Eirin-Lopez, J. Early Genotoxic and Cytotoxic Effects of the Toxic Dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima in the Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Toxins 2016, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.; Giri, S.S.; Jun, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Yun, S.; Park, S.C. Effects of algal toxin okadaic acid on the non-specific immune and antioxidant response of bay scallop (Argopecten irradians). Fish Shellfish. Immun. 2017, 65, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.; O’Halloran, J.; O’Brien, N.M.; van Pelt, F.F.N.A. Does the marine biotoxin okadaic acid cause DNA fragmentation in the blue mussel and the pacific oyster? Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 101, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Okada, Y. Comparative toxicity of dinophysistoxin-1 and okadaic acid in mice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 80, 616–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abal, P.; Louzao, M.C.; Suzuki, T.; Watanabe, R.; Vilariño, N.; Carrera, C.; Botana, A.M.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Toxic Action Reevaluation of Okadaic Acid, Dinophysistoxin-1 and Dinophysistoxin-2: Toxicity Equivalency Factors Based on the Oral Toxicity Study. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 49, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, D.; Signore, A.; Araneda, O.; Contreras, H.R.; Concha, M.; García, C. Toxicity and differential oxidative stress effects on zebrafish larvae following exposure to toxins from the okadaic acid group. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2020, 83, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, D.; Ríos, J.; Araneda, O.; Contreras, H.; Concha, M.; García, C. Oxidative Stress Parameters and Morphological Changes in Japanese Medaka (Oryzias latipes) after Acute Exposure to OA-Group Toxins. Life 2023, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Luo, Z.; Kang, J.; Guo, X.; Wang, C.; Jin, R.; Du, J.; Zheng, X.; Hii, K.S.; Fu, S.; et al. How Does Climate Change Influence the Regional Ecological–Social Risks of Harmful Dinoflagellates? A Predictive Study of China’s Coastal Waters. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Krock, B.; Lu, S.; Yang, W.; Gu, H. Morphology, molecular phylogeny and okadaic acid production of epibenthic Prorocentrum (Dinophyceae) species from the northern South China Sea. Algal Res. 2017, 22, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, A.; Qiu, J.; Yan, W.; Han, L.; Li, D.; Yin, C. Effects of lipophilic phycotoxin okadaic acid on the early development and transcriptional expression of marine medaka Oryzias melastigma. Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 260, 106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corriere, M.; Soliño, L.; Costa, P.R. Effects of the Marine Biotoxins Okadaic Acid and Dinophysistoxins on Fish. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, E.; de Melo Tarouco, F.; Alves, T.P.; Da Rosa, C.E.; Da Cunha Lana, P.; Mafra, L.L. Antioxidant responses and okadaic acid accumulation in Laeonereis acuta (Annelida) exposed to the harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum cf. lima. Toxicon 2021, 203, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-González, A.R.; Domit, C.; Rosa, K.M.S.; Mafra, L.L. Occurrence of potentially toxic microalgae and diarrhetic shellfish toxins in the digestive tracts of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) from southern Brazil. Harmful Algae 2023, 128, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.P.; Pinto, T.O.; Mafra, L.L. Frequent accumulation of diarrheic shellfish toxins by different bivalve species in a shallow subtropical estuary. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 40, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranda, L.; Corwin, S.; Hargraves, P.E. Prorocentrum lima (Dinophyceae) in northeastern USA coastal waters: I. Abundance and distribution. Harmful Algae 2007, 6, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, H.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, H.; Lü, S. Taxonomy and toxin profile of harmful benthic Prorocentrum (Dinophyceae) species from the Xisha Islands, South China Sea. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 40, 1171–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffier, N.; Gaudin, J.; Mezhoud, K.; Huet, H.; Chateau-Joubert, S.; Turquet, J.; Crespeau, F.; Edery, M. Toxicity to medaka fish embryo development of okadaic acid and crude extracts of Prorocentrum dinoflagellates. Toxicon 2007, 49, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, R.A.F.; Nascimento, S.M.; Santos, L.N. Sublethal fish responses to short-term food chain transfer of DSP toxins: The role of somatic condition. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020, 524, 151317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C.A.; Mafra, L.L.; Rossi, G.R.; Da Silva Trindade, E.; Matias, W.G. A simple method to evaluate the toxic effects of Prorocentrum lima extracts to fish (sea bass) kidney cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2022, 85, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.K.; Moon, S.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.N.; Jeong, E.J.; Rho, J. Isolation and Structural Identification of New Diol Esters of Okadaic Acid and Dinophysistoxin-1 from the Cultured Prorocentrum lima. Toxins 2025, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.P.; Mafra, L.L. Diel Variations in Cell Abundance and Trophic Transfer of Diarrheic Toxins during a Massive Dinophysis Bloom in Southern Brazil. Toxins 2018, 10, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Prithiviraj, B.; Tan, Z. Physiological Effects of Oxidative Stress Caused by Saxitoxin in the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.R. The C. elegans model in toxicity testing. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2017, 37, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, M.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Ding, G.; Liu, R.; Mu, J. Comparison of short-term toxicity of 14 common phycotoxins (alone and in combination) to the survival of brine shrimp Artemia salina. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2023, 42, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, V.; Azevedo, J.; Silva, M.; Ramos, V. Effects of Marine Toxins on the Reproduction and Early Stages Development of Aquatic Organisms. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajuzie, C.C. Toxic Prorocentrum lima induces abnormal behaviour in juvenile sea bass. J. Appl. Phycol. 2008, 20, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuerger, L.T.D.; Sprenger, H.; Krasikova, K.; Templin, M.; Stahl, A.; Herfurth, U.M.; Sieg, H.; Braeuning, A. A multi-omics approach to elucidate okadaic acid-induced changes in human HepaRG hepatocarcinoma cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 2919–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, M.I.; Sana, T.; Panneerselvan, L.; Dharmarajan, R.; Megharaj, M. Acute Toxicity and Transgenerational Effects of Perfluorobutane Sulfonate on Caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelter, J.F.; Garcia, S.C.; Göethel, G.; Charão, M.F.; de Melo, L.M.; Brandelli, A. Acute Toxicity Evaluation of Phosphatidylcholine Nanoliposomes Containing Nisin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Molecules 2023, 28, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Gong, C.; An, W.; Winblad, B.; Cowburn, R.F.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Okadaic Acid Induced Inhibition of Protein Phosphatase 2A Produces Activation of Mitogen Activated Protein Kinases ERK1/2, MEK1/2, and p70 S6, Similar to That in Alzheimer’s Disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, R. Is Protein Phosphatase Inhibition Responsible for the Toxic Effects of Okadaic Acid in Animals? Toxins 2013, 5, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Sun, G.; Qiu, J.; Li, A. Occurrence and variation of lipophilic shellfish toxins in phytoplankton, shellfish and seawater samples from the aquaculture zone in the Yellow Sea, China. Toxicon 2017, 127, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Geraldo, R.D.J.; García-Lagunas, N.; Hernández-Saavedra, N.Y. Crassostrea gigas exposure to the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima: Histological and gene expression effects on the digestive gland. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 120, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Faraldo, M.V.; Vieira, L.R.; Eirin-Lopez, J.M.; Méndez, J.; Guilhermino, L. Transcriptional and biochemical analysis of antioxidant enzymes in the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis during experimental exposures to the toxic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 129, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Li, D.; Cai, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, W. Toxic Responses of Different Shellfish Species after Exposure to Prorocentrum lima, a DSP Toxins Producing Dinoflagellate. Toxins 2022, 14, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, R.A.F.; Santiago, T.C.; Carvalho, W.F.; Silva, E.D.S.; Da Silva, P.M.; Nascimento, S.M. Impacts of the toxic benthic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima on the brown mussel Perna perna: Shell-valve closure response, immunology, and histopathology. Mar. Environ. Res. 2019, 146, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windust, A.J.; Hu, T.; Wright, J.L.C.; Quilliam, M.A.; McLachlan, J.L. Oxidative metabolism by Thalassiosira weissflogii (Bacillariophyceae) of a diol-ester of okadaic acid, the diarrhetic shellfish poisoning. J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikehara, T.; Chikanishi, K.; Oshiro, N. Specification of the Okadaic Acid Equivalent for Okadaic Acid, Dinophysistoxin-1, and Dinophysistoxin-2 Based on Protein Phosphatase 2A Inhibition and Cytotoxicity Assays Using Neuro 2A Cell Line. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.T.; Hansen, P.J.; Krock, B.; Vismann, B. Accumulation, transformation and breakdown of DSP toxins from the toxic dinoflagellate Dinophysis acuta in blue mussels, Mytilus edulis. Toxicon 2016, 117, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Ji, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wang, S.; Ai, Q.; Li, A. Response of fatty acids and lipid metabolism enzymes during accumulation, depuration and esterification of diarrhetic shellfish toxins in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis). Ecotox. Environ. Safe 2020, 206, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, T.; Sandvik, M.; Lundve, B.; Lindegarth, S. Profiles and levels of fatty acid esters of okadaic acid group toxins and pectenotoxins during toxin depuration. Part II: Blue mussels (Mytilus edulis) and flat oyster (Ostrea edulis). Toxicon 2008, 52, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; LeBlanc, P.; Burton, I.W.; Walter, J.A.; McCarron, P.; Melanson, J.E.; Strangman, W.K.; Wright, J.L.C. Sulfated diesters of okadaic acid and DTX-1: Self-protective precursors of diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP) toxins. Harmful Algae 2017, 63, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahms, H.; Hagiwara, A.; Lee, J. Ecotoxicology, ecophysiology, and mechanistic studies with rotifers. Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 101, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, C.; Wu, H.; Zheng, G.; Lu, L.; Tan, Z. Enhanced Toxicity of Diol-Estered Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins Across Trophic Levels: Evidence from Caenorhabditis elegans and Mytilus galloprovincialis. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120459

Chen C, Wu H, Zheng G, Lu L, Tan Z. Enhanced Toxicity of Diol-Estered Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins Across Trophic Levels: Evidence from Caenorhabditis elegans and Mytilus galloprovincialis. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120459

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Caihong, Haiyan Wu, Guanchao Zheng, Limin Lu, and Zhijun Tan. 2025. "Enhanced Toxicity of Diol-Estered Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins Across Trophic Levels: Evidence from Caenorhabditis elegans and Mytilus galloprovincialis" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120459

APA StyleChen, C., Wu, H., Zheng, G., Lu, L., & Tan, Z. (2025). Enhanced Toxicity of Diol-Estered Diarrhetic Shellfish Toxins Across Trophic Levels: Evidence from Caenorhabditis elegans and Mytilus galloprovincialis. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120459