Anti-Cancer Activity of Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Algal Extract: Hopes and Fears of a Possible Alternative Treatment for Canine Mast Cell Tumor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Preliminary Cytotoxicity Screening of Algae Extracts

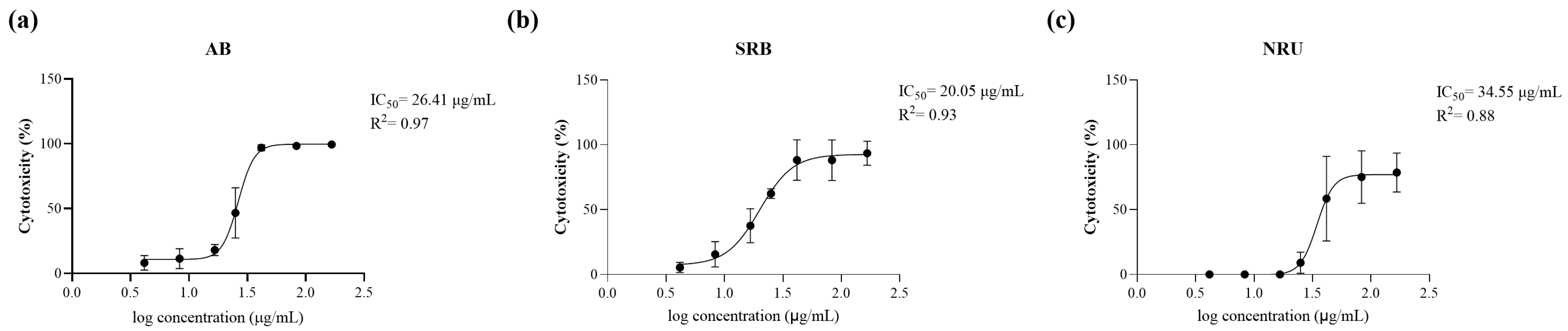

2.2. SCE Cytotoxicity

2.3. Selective SCE Cytotoxicity Against Tumor Cell Lines

2.4. Chemical Characterization of SCE

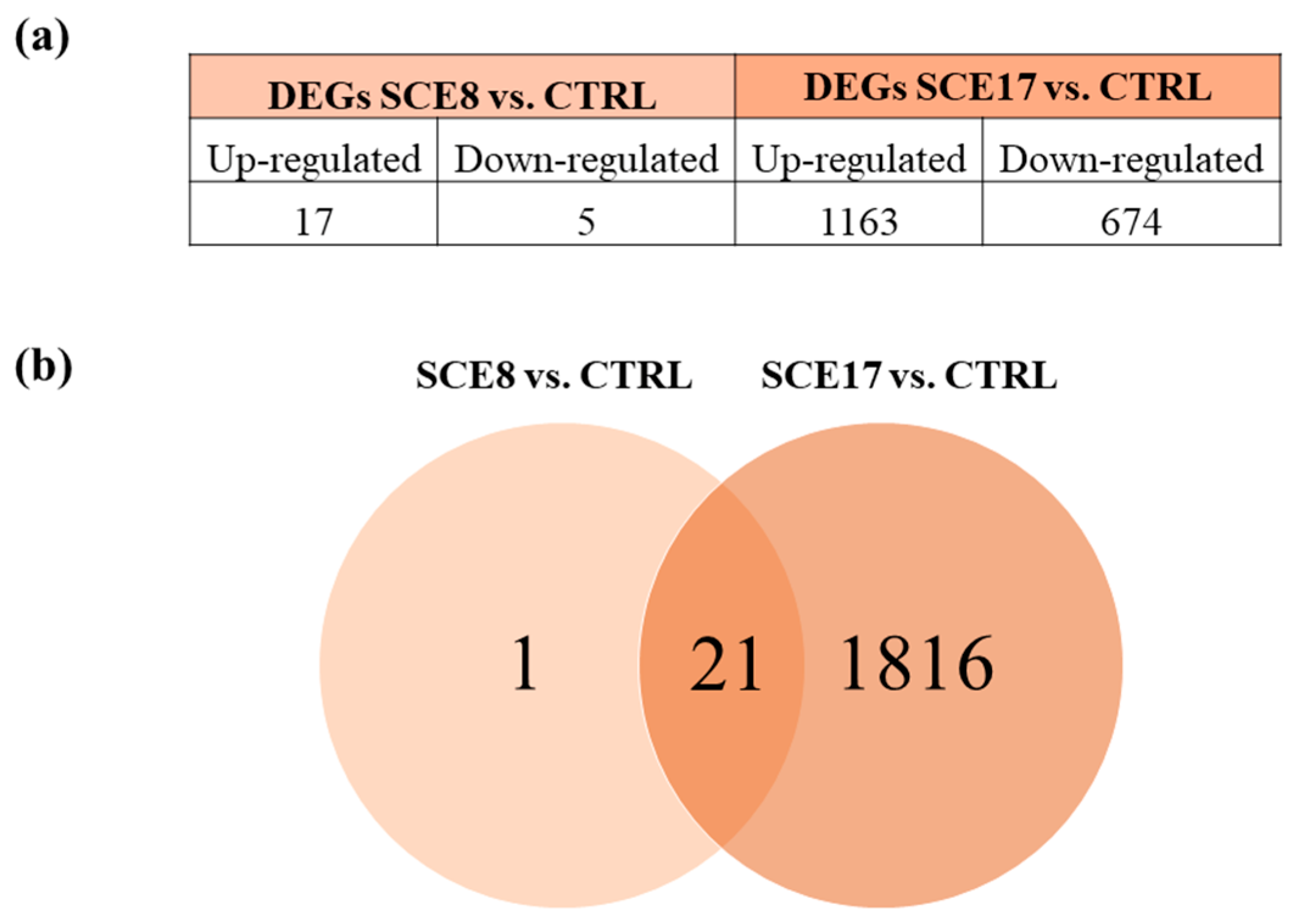

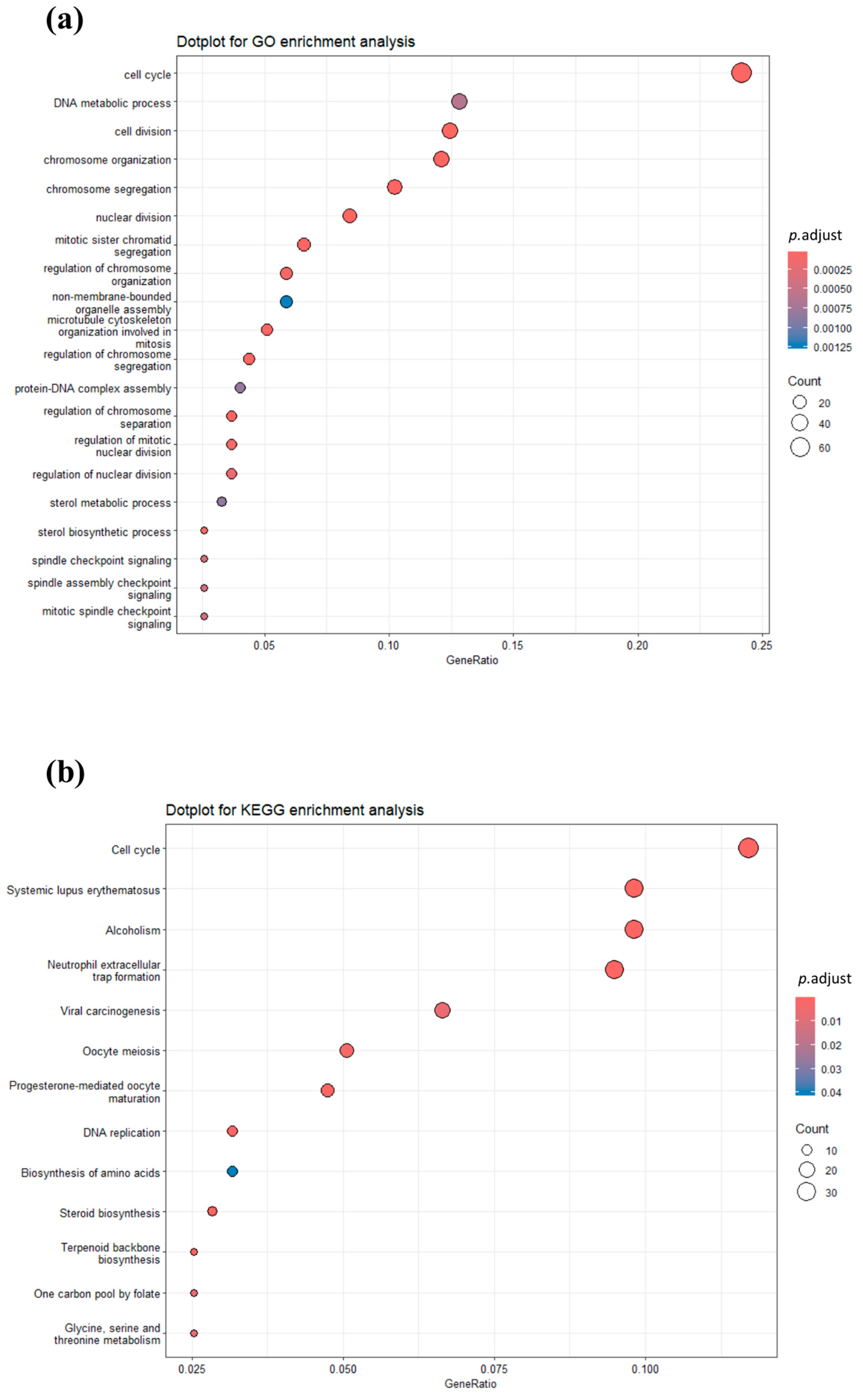

2.5. Differential Gene Expression (DGE) and Functional Analyses

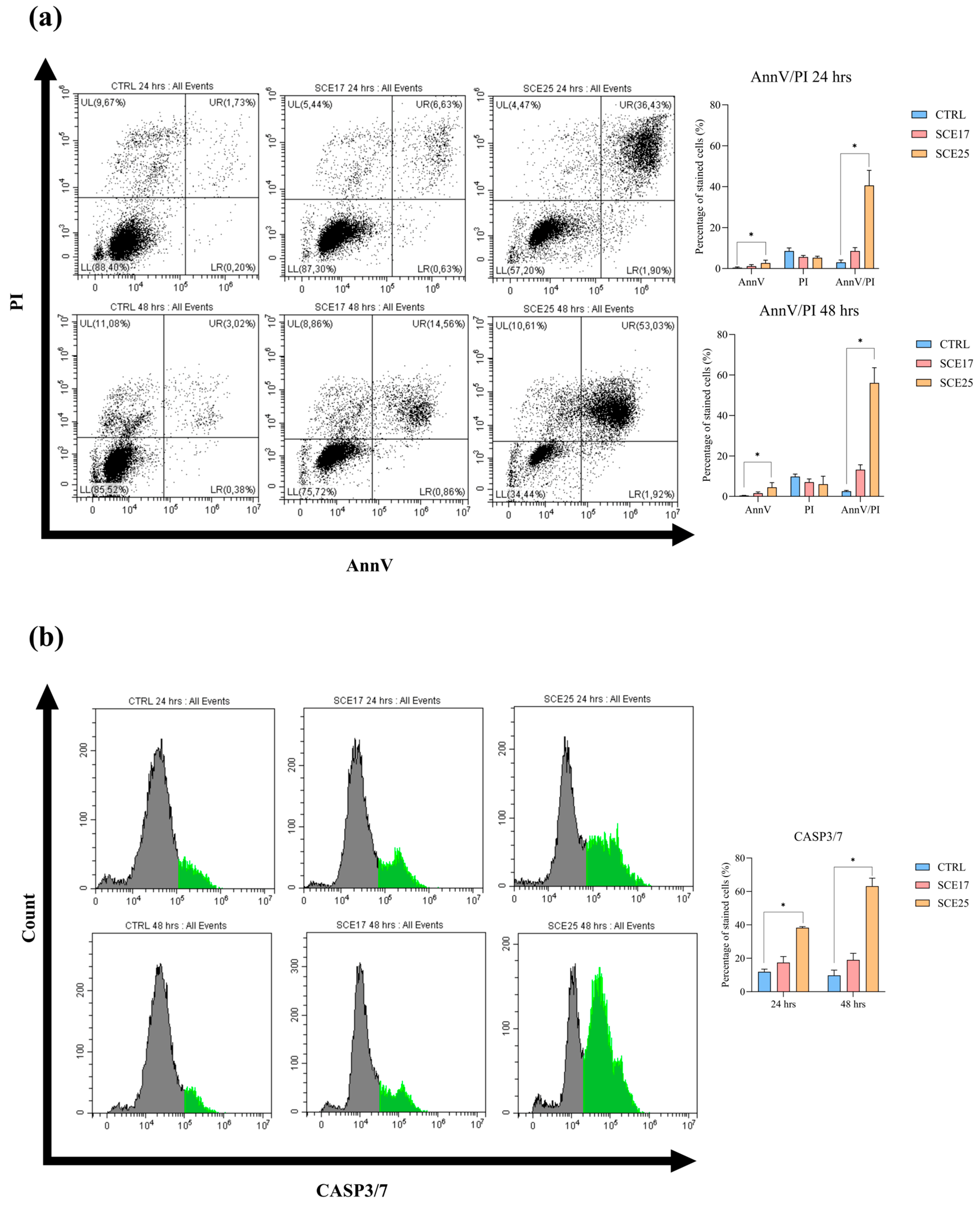

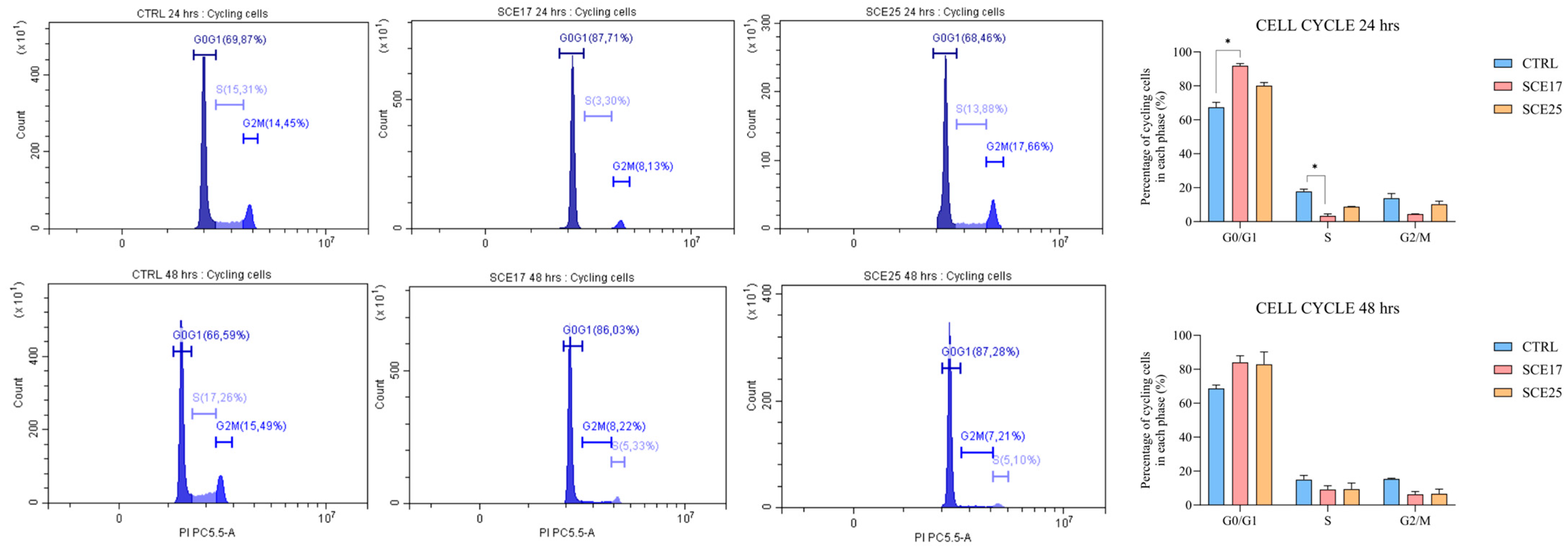

2.6. Confirmatory Assays

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Algal Sampling

4.3. Preparation of Algal Crude Extracts

4.4. Cell Culture

4.5. Preliminary Cytotoxicity Screening of Algal Crude Extracts

4.6. SCE Cytotoxicity

4.7. Selectivity of SCE Against Tumor Cell Lines

4.8. Chemical Characterization of SCE

4.9. Incubation of Cells for Gene Expression Analysis (RNA-seq) and Confirmatory Assays (qPCR, Flow Cytometry, Immunoblotting)

4.10. RNA Extraction

4.11. RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

4.12. DGE Analysis and Functional Analysis

4.13. Confirmatory Assays (qPCR, Flow Cytometry, Immunoblotting)

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Alamar Blue |

| A/G | Alanine-Glutamine |

| AnnV | Annexin V |

| AnnV/PI | Annexin V/Propidium iodide |

| AOAH | Acyloxyacyl Hydrolase |

| ATR_FTIR | Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma |

| Bcl-XL | B-cell lymphoma extra large |

| BET | Betulin |

| BH | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| CASP3/7 | Caspase 3/7 |

| CCNB2 | Cyclin B2 |

| CDKN1A | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A |

| CPT1A | Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A |

| CTRL | Control |

| CXCL13 | CXC Motif Chemokine Ligand 13 |

| DAD | Diode array |

| ΔΔCT | Comparative Cycle Threshold |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DGE | Differential Gene Expression |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulphoxide |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| FAME | Fatty acid methyl esters |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| fc | Fold changes |

| FOS | FOS proto-oncogene |

| GC/MS | Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| H-ESI | Heated electrospray ionization |

| HK2 | Hexokinase 2 |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| LAMC2 | Laminin Subunit Gamma 2 |

| JUNB | JUNB proto-oncogene |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| MCT | Mast cell tumor |

| MDCK | Madin-Darby canine kidney |

| MELPATH | Mevalonate pathway |

| MEM | Minimum Essential Medium |

| NCs | Natural compounds |

| NEAA | Non-essential amino acids |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| NRU | Neutral Red Uptake |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| P/S | Penicillin-streptomycin |

| PYR | Sodium pyruvate |

| qPCR | Quantitative RT-PCR |

| RAD51 | RAD51 Recombinase |

| RIN | RNA Integrity Number |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| Rt | Retention times |

| PIM2 | Pim-2 Proto-Oncogene |

| PLK1 | Polo-like kinase 1 |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulphate |

| SC | Sphaerococcus coronopifolius |

| SCE | Sphaerococcus coronopifolius extract |

| SCE8 | Sphaerococcus coronopifolius extract, 8.33 µg/mL |

| SCE17 | Sphaerococcus coronopifolius extract, 16.66 µg/mL |

| SCE25 | Sphaerococcus coronopifolius extract, 25.00 µg/mL |

| SI | selectivity index |

| SQLE | Squalene Epoxidase |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| TBST | Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

| TMM | Trimmed mean of M-values |

| TP53INP1 | Tumor Protein 53 Inducible Nuclear Protein 1 |

References

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Vallinas, M.; González-Castejón, M.; Rodríguez-Casado, A.; Ramírez de Molina, A. Dietary Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention and Therapy: A Complementary Approach with Promising Perspectives. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salaroli, R.; Andreani, G.; Bernardini, C.; Zannoni, A.; La Mantia, D.; Protti, M.; Forni, M.; Mercolini, L.; Isani, G. Anticancer Activity of an Artemisia Annua L. Hydroalcoholic Extract on Canine Osteosarcoma Cell Lines. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Mei, C.; Xian, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H. Toosendanin-induced Apoptosis of CMT-U27 Is Mediated through the Mitochondrial Apoptotic Pathway. Vet. Compar. Oncol. 2023, 21, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, B.; Alves, L. Synergy in Plant Medicines. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedney, A.; Salah, P.; Mahoney, J.A.; Krick, E.; Martins, R.; Scavello, H.; Lenz, J.A.; Atherton, M.J. Evaluation of the Anti-tumour Activity of Coriolus versicolor Polysaccharopeptide (I’m-Yunity) Alone or in Combination with Doxorubicin for Canine Splenic Hemangiosarcoma. Vet. Compar. Oncol. 2022, 20, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C.B.; Bayle, J.; Biourge, V.; Wakshlag, J.J. Effects and Synergy of Feed Ingredients on Canine Neoplastic Cell Proliferation. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C.B.; Bayle, J.; Biourge, V.; Wakshlag, J.J. Cellular Effects of a Turmeric Root and Rosemary Leaf Extract on Canine Neoplastic Cell Lines. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Arellanes, S.; Salgado-Garciglia, R.; Báez-Magaña, M.; Ochoa-Zarzosa, A.; López-Meza, J.E. Cytotoxicity of a Lipid-Rich Extract from Native Mexican Avocado Seed (Persea americana Var. Drymifolia) on Canine Osteosarcoma D-17 Cells and Synergistic Activity with Cytostatic Drugs. Molecules 2021, 26, 4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nardi, A.B.; dos Santos Horta, R.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; de Paiva, F.N.; Linhares, L.C.M.; Firmo, B.F.; Ruiz Sueiro, F.A.; de Oliveira, K.D.; Lourenço, S.V.; De Francisco Strefezzi, R.; et al. Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment of Canine Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Mast Cell Tumors. Cells 2022, 11, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, M.; Hadzijusufovic, E.; Hermine, O.; Dacasto, M.; Marconato, L.; Bauer, K.; Peter, B.; Gamperl, S.; Eisenwort, G.; Jensen-Jarolim, E.; et al. Comparative Oncology: The Paradigmatic Example of Canine and Human Mast Cell Neoplasms. Vet. Compar. Oncol. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, S.; Vecchiarelli, L.; Pagni, E.; Gramanzini, M. The Role of Canine Models of Human Cancer: Overcoming Drug Resistance Through a Transdisciplinary “One Health, One Medicine” Approach. Cancers 2025, 17, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Chen, Y.; Shan, S.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhao, C. Marine Algae-derived Characterized Bioactive Compounds as Therapy for Cancer: A Review on Their Classification, Mechanism of Action, and Future Perspectives. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 4053–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazzini, S.; Rossi, L. Anticancer Properties of Macroalgae: A Comprehensive Review. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication; National University of Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2025; Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Rodrigues, D.; Alves, C.; Horta, A.; Pinteus, S.; Silva, J.; Culioli, G.; Thomas, O.P.; Pedrosa, R. Antitumor and Antimicrobial Potential of Bromoditerpenes Isolated from the Red Alga, Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, B.; Narayanan, M. Enhancing Cancer Treatment with Marine Algae–Derived Bioactive Chemicals: A Review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verza, F.A.; Da Silva, G.C.; Nishimura, F.G. The Impact of Oxidative Stress and the NRF2-KEAP1-ARE Signaling Pathway on Anticancer Drug Resistance. Oncol. Res. 2025, 33, 1819–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Wilson, I.; Orton, T.; Pognan, F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (Resazurin) Fluorescent Dye for the Assessment of Mammalian Cell Cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 5421–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.; Baroutian, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, B.; Ying, T.; Lu, J. Combination of Marine Bioactive Compounds and Extracts for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1047026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elias, N.; Farag, M.A.; Chen, L.; Saeed, A.; Hegazy, M.-E.F.; Moustafa, M.S.; Abd El-Wahed, A.; Al-Mousawi, S.M.; Musharraf, S.G.; et al. Marine Natural Products: A Source of Novel Anticancer Drugs. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaky, A.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Eun, J.B.; Shim, J.H.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Bioactivities, Applications, Safety, and Health Benefits of Bioactive Peptides From Food and By-Products: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 815640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.H.; Cho, J.Y. Comparative Oncology: Overcoming Human Cancer through Companion Animal Studies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincze, O.; Spada, B.; Bilder, D.; Cagan, A.; DeGregori, J.; Gorbunova, V.; Maley, C.C.; Schiffman, J.D.; Seluanov, A.; Giraudeau, M.; et al. Advancing Cancer Research via Comparative Oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2025, 25, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.S.; Ngo, D.H.; Kim, S.K. Marine Algae as a Potential Pharmaceutical Source for Anti-Allergic Therapeutics. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueck, T.; Seidel, A.; Fuhrmann, H. Effects of Essential Fatty Acids on Mediators of Mast Cells in Culture. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2003, 68, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueck, T.; Seidel, A.; Baumann, D.; Meister, A.; Fuhrmann, H. Alterations of Mast Cell Mediator Production and Release by Gamma-Linolenic and Docosahexaenoic Acid. Vet. Dermatol. 2004, 15, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, R.; Federico, S.; Glaviano, F.; Somma, E.; Zupo, V.; Costantini, M. Bioactive Compounds from Marine Sponges and Algae: Effects on Cancer Cell Metabolome and Chemical Structures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.M.N.; Dao, T.K.D.; Tran, T.T.T.; Trinh, T.T.H.; Nguyen, L.N.; Dam, D.T.; Guerrae, I.R.; Doan, L.P. Lipid Composition, Cytotoxic and Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition Effects of Two Brown Algae Species Lobophora tsengii and Lobophora australis. J. Oleo Sci. 2024, 73, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, P.; Aulner, N.; Bickle, M.; Davies, A.M.; Nery, E.D.; Ebner, D.; Montoya, M.C.; Östling, P.; Pietiäinen, V.; Price, L.S.; et al. Screening Out Irrelevant Cell-based Models of Disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, M.; Seghatoleslam, A.; Namavari, M.; Amiri, A.; Fahmidehkar, M.A.; Ramezani, A.; Eftekhar, E.; Hosseini, A.; Erfani, N.; Fakher, S. Selective Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis-Induction of Cyrtopodion scabrum Extract Against Digestive Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Cancer Manag. 2017, 10, 111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoccia, D.; Ravaioli, S.; Santi, S.; Mariani, V.; Santarcangelo, C.; De Filippis, A.; Montanaro, L.; Arciola, C.R.; Daglia, M. Exploring the Anticancer Effects of Standardized Extracts of Poplar-Type Propolis: In Vitro Cytotoxicity toward Cancer and Normal Cell Lines. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haglund, C.; Aleskog, A.; Nygren, P.; Gullbo, J.; Höglund, M.; Wickström, M.; Larsson, R.; Lindhagen, E. In Vitro Evaluation of Clinical Activity and Toxicity of Anticancer Drugs Using Tumor Cells from Patients and Cells Representing Normal Tissues. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2012, 69, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Pinteus, S.; Horta, A.; Pedrosa, R. High Cytotoxicity and Anti-Proliferative Activity of Algae Extracts on an in Vitro Model of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Silva, J.; Pinteus, S.; Gaspar, H.; Alpoim, M.C.; Botana, L.M.; Pedrosa, R. From Marine Origin to Therapeutics: The Antitumor Potential of Marine Algae-Derived Compounds. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Serrano, E.; Silva, J.; Rodrigues, C.; Pinteus, S.; Gaspar, H.; Botana, L.M.; Alpoim, M.C.; Pedrosa, R. Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Bromoterpenes as Potential Cancer Stem Cell-Targeting Agents. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 128, 110275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Silva, J.; Pinteus, S.; Alonso, E.; Alvariño, R.; Duarte, A.; Marmitt, D.; Goettert, M.I.; Gaspar, H.; Alfonso, A.; et al. Cytotoxic Mechanism of Sphaerodactylomelol, an Uncommon Bromoditerpene Isolated from Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Molecules 2021, 26, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Silva, J.; Pintéus, S.; Guedes, R.A.; Guedes, R.C.; Alvariño, R.; Freitas, R.; Goettert, M.I.; Gaspar, H.; Alfonso, A.; et al. Bromoditerpenes from the Red Seaweed Sphaerococcus coronopifolius as Potential Cytotoxic Agents and Proteasome Inhibitors and Related Mechanisms of Action. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etahiri, S.; Bultel-Poncé, V.; Caux, C.; Guyot, M. New Bromoditerpenes from the Red Alga Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 1024–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrniotopoulos, V.; Vagias, C.; Roussis, V. Sphaeroane and Neodolabellane Diterpenes from the Red Alga Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Mar. Drugs 2009, 7, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrniotopoulos, V.; Vagias, C.; Bruyère, C.; Lamoral-Theys, D.; Kiss, R.; Roussis, V. Structure and in Vitro Antitumor Activity Evaluation of Brominated Diterpenes from the Red Alga Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1321–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrniotopoulos, V.; De Andrade Tomaz, A.C.; De Fátima Vanderlei De Souza, M.; Da Cunha, E.V.L.; Kiss, R.; Mathieu, V.; Ioannou, E.; Roussis, V. Halogenated Diterpenes with in Vitro Antitumor Activity from the Red Alga Sphaerococcus coronopifolius. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, D.; Fortunato, M.A.G.; Silva, J.; Pingo, M.; Martins, A.; Afonso, C.A.M.; Pedrosa, R.; Siopa, F.; Alves, C. Sphaerococcenol A Derivatives: Design, Synthesis, and Cytotoxicity. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adepoju, F.O.; Duru, K.C.; Li, E.; Kovaleva, E.G.; Tsurkan, M.V. Pharmacological Potential of Betulin as a Multitarget Compound. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, R.; Pawlak, A.; Henklewska, M.; Sysak, A.; Wen, L.; Yi, J.E.; Obmińska-Mrukowicz, B. Antitumor Activity of Betulinic Acid and Betulin in Canine Cancer Cell Lines. In Vivo 2018, 32, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, P.J.; Yu, R.; Longo, J.; Archer, M.C.; Penn, L.Z. The Interplay between Cell Signalling and the Mevalonate Pathway in Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurnher, M.; Gruenbacher, G.; Nussbaumer, O. Regulation of Mevalonate Metabolism in Cancer and Immune Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2013, 1831, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Recio, C.; Aranda-Tavío, H.; Guerra-Rodríguez, M.; García-Castellano, J.M.; Fernández-Pérez, L. The Mevalonate Pathway, a Metabolic Target in Cancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 626971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasunción, M.A.; Martínez-Botas, J.; Martín-Sánchez, C.; Busto, R.; Gómez-Coronado, D. Cell Cycle Dependence on the Mevalonate Pathway: Role of Cholesterol and Non-Sterol Isoprenoids. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022, 196, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Bell, E.; Mischel, P.; Chakravarti, A. Targeting SREBP-1-Driven Lipid Metabolism to Treat Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Feng, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y. SREBP-1 Inhibitor Betulin Enhances the Antitumor Effect of Sorafenib on Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Restricting Cellular Glycolytic Activity. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laka, K.; Makgoo, L.; Mbita, Z. Cholesterol-Lowering Phytochemicals: Targeting the Mevalonate Pathway for Anticancer Interventions. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 841639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed-Pastor, W.A.; Mizuno, H.; Zhao, X.; Langerød, A.; Moon, S.H.; Rodriguez-Barrueco, R.; Barsotti, A.; Chicas, A.; Li, W.; Polotskaia, A.; et al. Mutant P53 Disrupts Mammary Tissue Architecture via the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell 2012, 148, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Idate, R.; Cronise, K.E.; Gustafson, D.L.; Duval, D.L. Identifying Candidate Druggable Targets in Canine Cancer Cell Lines Using Whole-Exome Sequencing. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1460–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X. PPM1D Regulates P21 Expression via Dephoshporylation at Serine 123. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Kent, M.S.; Rodriguez, C.O.; Chen, X. Establishment of a Dog Model for the P53 Family Pathway and Identification of a Novel Isoform of P21 Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009, 7, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Ortiz, E.; de la Cruz-López, K.G.; Becerril-Rico, J.; Sarabia-Sánchez, M.A.; Ortiz-Sánchez, E.; García-Carrancá, A. Mutant P53 Gain-of-Function: Role in Cancer Development, Progression, and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 607670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.H.; Li, N. Altered Metabolism in Cancer: Insights into Energy Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chard Dunmall, L.S.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, L. Natural Products Targeting Glycolysis in Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1036502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Shi, Z. CPT1A in cancer: Tumorigenic Roles and Therapeutic Implications. Biocell 2023, 47, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, V.C.; Butterfield, H.E.; Poral, A.H.; Yan, M.J.; Yang, K.L.; Pham, C.D.; Muller, F.L. Why Great Mitotic Inhibitors Make Poor Cancer Drugs. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 924–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, N.H.; Jung, Y.P.; Kim, A.; Kim, T.; Ma, J.Y. Induction of Apoptotic Cell Death by Betulin in Multidrug-Resistant Human Renal Carcinoma Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Hsieh, C.P.; Huang, Y.F.; Chang, I.L. Betulin Inhibits MTOR and Induces Autophagy to Promote Apoptosis in Human Osteosarcoma Cell Lines. Environ. Toxicol. 2020, 35, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzeski, W.; Stepulak, A.; Szymański, M.; Sifringer, M.; Kaczor, J.; Wejksza, K.; Zdzisińska, B.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M. Betulinic Acid Decreases Expression of Bcl-2 and Cyclin D1, Inhibits Proliferation, Migration and Induces Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2006, 374, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drag, M.; Surowiak, P.; Malgorzata, D.Z.; Dietel, M.; Lage, H.; Oleksyszyn, J. Comparision of the Cytotoxic Effects of Birch Bark Extract, Betulin and Betulinic Acid towards Human Gastric Carcinoma and Pancreatic Carcinoma Drug-Sensitive and Drug-Resistant Cell Lines. Molecules 2009, 14, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šiman, P.; Filipová, A.; Tichá, A.; Niang, M.; Bezrouk, A.; Havelek, R. Effective Method of Purification of Betulin from Birch Bark: The Importance of Its Purity for Scientific and Medicinal Use. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, J.M.; Damasceno, J.L.; Oliveira, R.A.M.; Júnior Dias, H.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Tavares, D.C. Cytotoxicity Screening of Essential Oils in Cancer Cell Lines. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucignat, G.; Bassan, I.; Giantin, M.; Pauletto, M.; Bardhi, A.; Iori, S.; Lopparelli, R.M.; Barbarossa, A.; Zaghini, A.; Novelli, E.; et al. Does Bentonite Cause Cytotoxic and Whole-Transcriptomic Adverse Effects in Enterocytes When Used to Reduce Aflatoxin B1 Exposure? Toxins 2022, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, C.E.E.; Lakshmi, P.K.; Meenakshi, S.; Vaidyanathan, S.; Srisudha, S.; MMary, M.B. Biomolecular Transitions and Lipid Accumulation in Green Microalgae Monitored by FTIR and Raman Analysis. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 224, 117382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC. A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-Optimal Probabilistic RNA-Seq Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneson, C.; Love, M.I.; Robinson, M.D. Differential Analyses for RNA-Seq: Transcript-Level Estimates Improve Gene-Level Inferences. F1000Research 2015, 4, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durinck, S.; Spellman, P.T.; Birney, E.; Huber, W. Mapping Identifiers for the Integration of Genomic Datasets with the R/Bioconductor Package BiomaRt. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. EdgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, A.T.L.; Chen, Y.; Smyth, G.K. It’s DE-Licious: A Recipe for Differential Expression Analyses of RNA-Seq Experiments Using Quasi-Likelihood Methods in EdgeR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1418, 391–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasaol, J.C.; Dejnaka, E.; Mucignat, G.; Bajzert, J.; Henklewska, M.; Obmińska-Mrukowicz, B.; Giantin, M.; Pauletto, M.; Zdyrski, C.; Dacasto, M.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Olaparib Induces DNA Damage and Acts as a Drug Sensitizer in an in Vitro Model of Canine Hematopoietic Cancer. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giantin, M.; Granato, A.; Baratto, C.; Marconato, L.; Vascellari, M. Global Gene Expression Analysis of Canine Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumor: Could Molecular Profiling Be Useful for Subtype Classification and Prognostication? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 95481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresu, L.; Giantin, M.; Morello, E.; Vascellari, M.; Castagnaro, M.; Lopparelli, R.; Zancanella, V.; Granato, A.; Garbisa, S.; Aricò, A.; et al. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Canine Mammary Tumors. BMC Vet. Res. 2011, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giantin, M.; Baratto, C.; Marconato, L.; Vascellari, M.; Mutinelli, F.; Dacasto, M.; Granato, A. Transcriptomic Analysis Identified Up-Regulation of a Solute Carrier Transporter and UDP Glucuronosyltransferases in Dogs with Aggressive Cutaneous Mast Cell Tumours. Vet. J. 2016, 212, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mucignat, G.; Lakhdar, F.; Maghrebi, H.; Dejnaka, E.; Lucatello, L.; Benhniya, B.; Capolongo, F.; Etahiri, S.; Pauletto, M.; Pawlak, A.; et al. Anti-Cancer Activity of Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Algal Extract: Hopes and Fears of a Possible Alternative Treatment for Canine Mast Cell Tumor. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120457

Mucignat G, Lakhdar F, Maghrebi H, Dejnaka E, Lucatello L, Benhniya B, Capolongo F, Etahiri S, Pauletto M, Pawlak A, et al. Anti-Cancer Activity of Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Algal Extract: Hopes and Fears of a Possible Alternative Treatment for Canine Mast Cell Tumor. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):457. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120457

Chicago/Turabian StyleMucignat, Greta, Fatima Lakhdar, Hanane Maghrebi, Ewa Dejnaka, Lorena Lucatello, Bouchra Benhniya, Francesca Capolongo, Samira Etahiri, Marianna Pauletto, Aleksandra Pawlak, and et al. 2025. "Anti-Cancer Activity of Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Algal Extract: Hopes and Fears of a Possible Alternative Treatment for Canine Mast Cell Tumor" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120457

APA StyleMucignat, G., Lakhdar, F., Maghrebi, H., Dejnaka, E., Lucatello, L., Benhniya, B., Capolongo, F., Etahiri, S., Pauletto, M., Pawlak, A., Giantin, M., & Dacasto, M. (2025). Anti-Cancer Activity of Sphaerococcus coronopifolius Algal Extract: Hopes and Fears of a Possible Alternative Treatment for Canine Mast Cell Tumor. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 457. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120457