A2BAR-Mediated Antiproliferative and Anticancer Effects of Okhotoside A1-1 in Monolayer and 3D Culture of Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells

Abstract

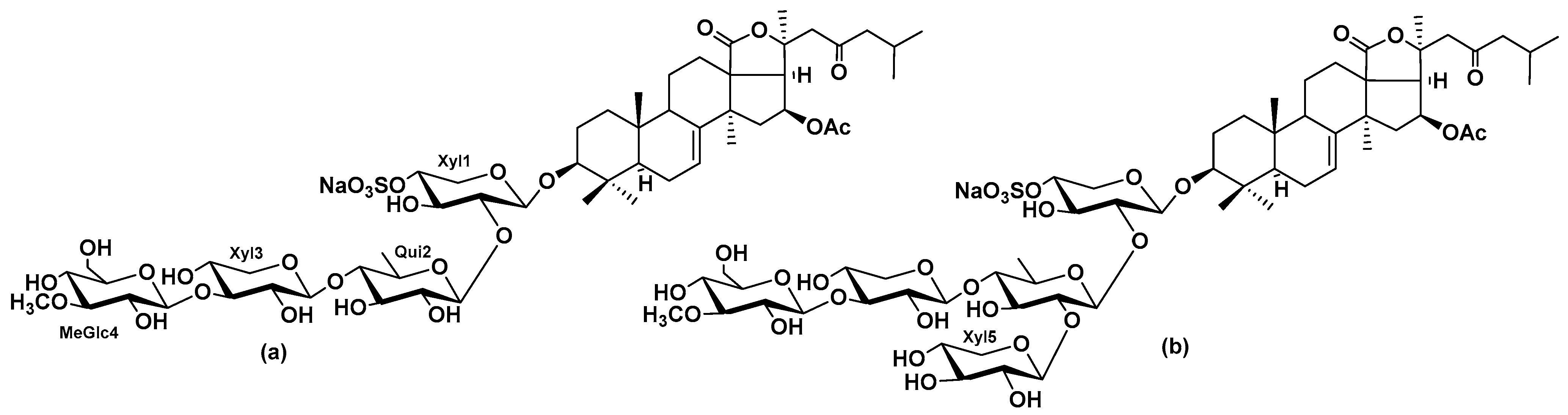

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Dependence of the Antiproliferative Action of Okh Against MDA-MB-231 Cell on A2BAR

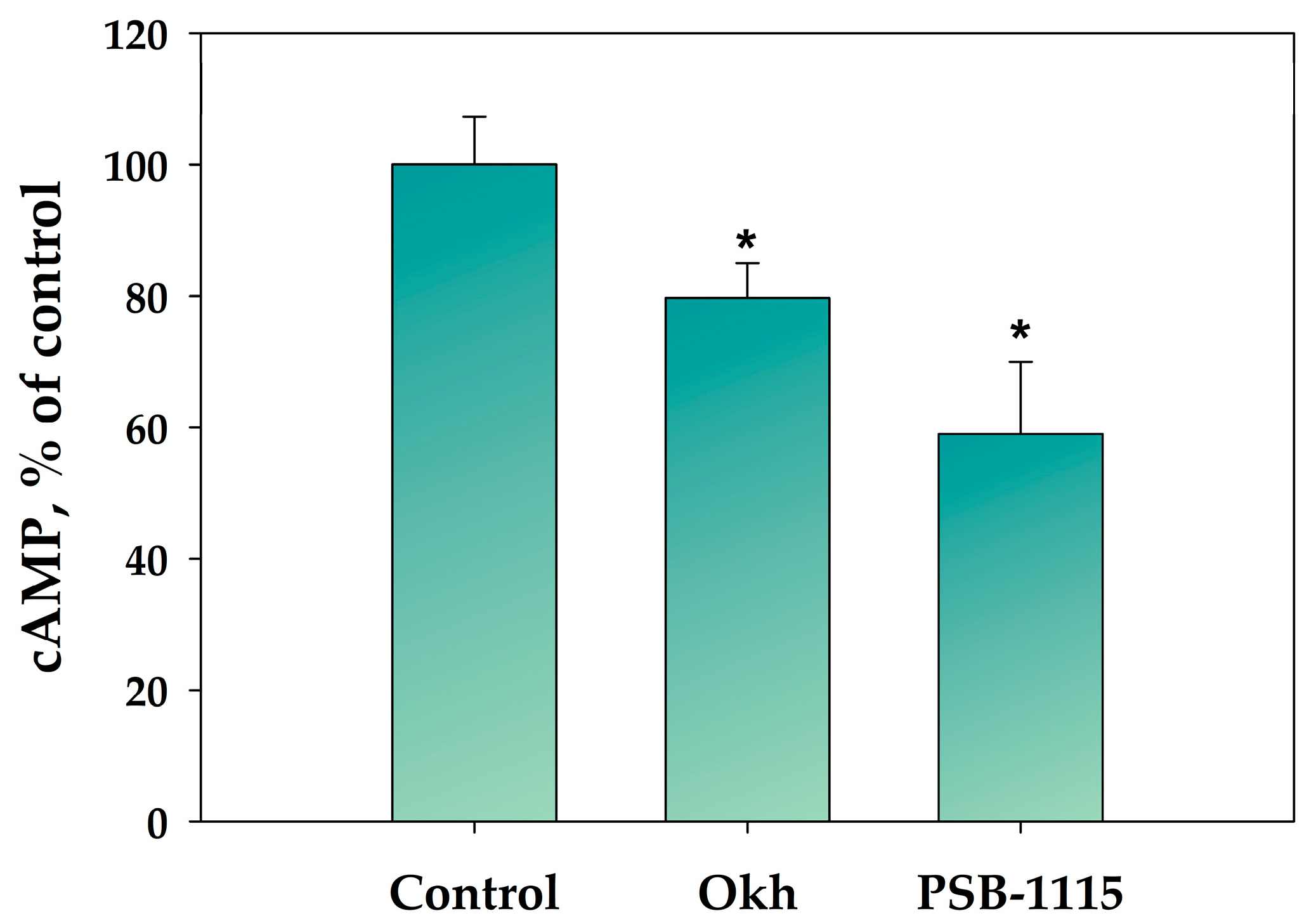

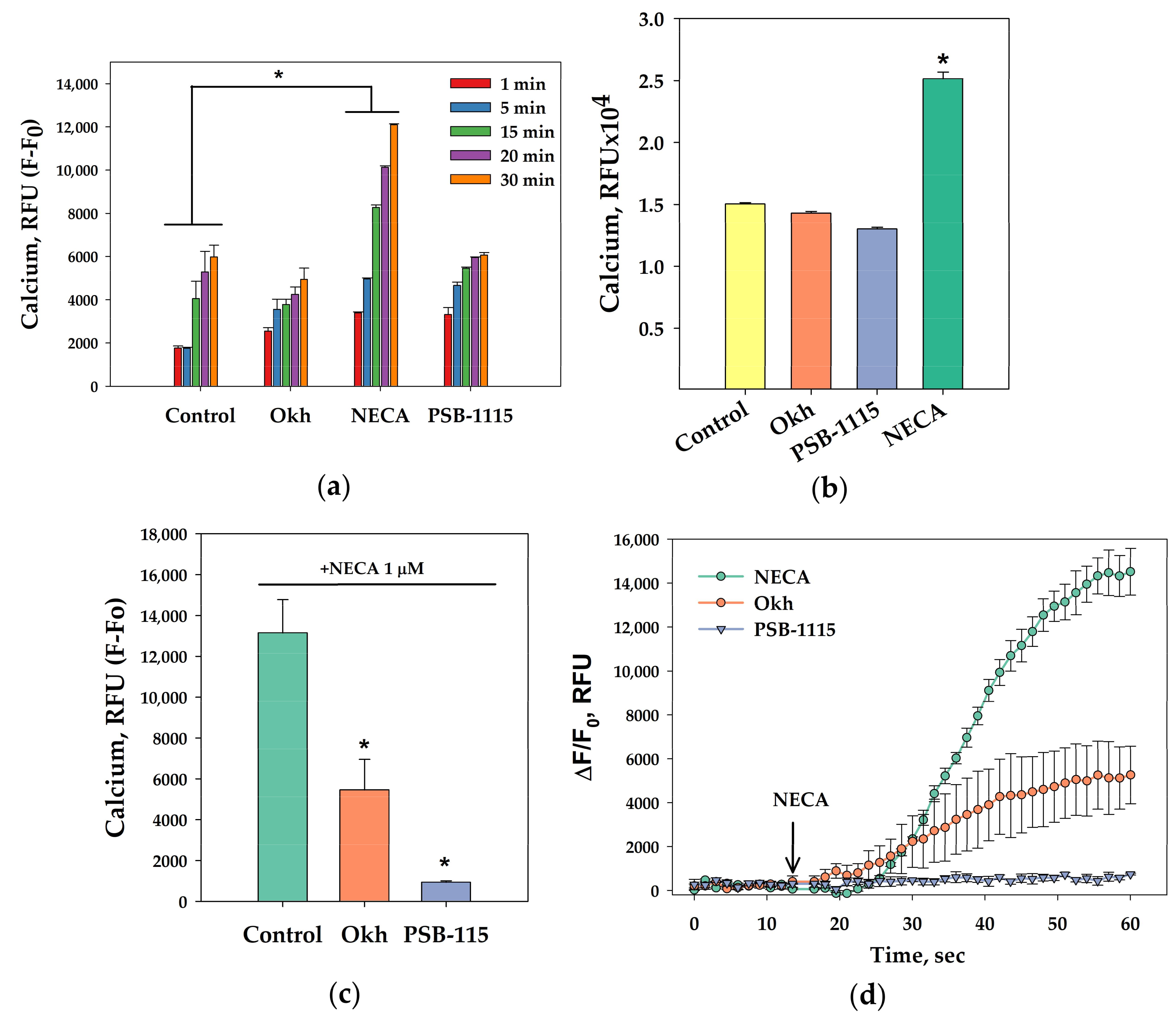

2.2. The Influence of Okh on Intracellular cAMP and Ca2+ Levels in MDA-MB-231 Cells

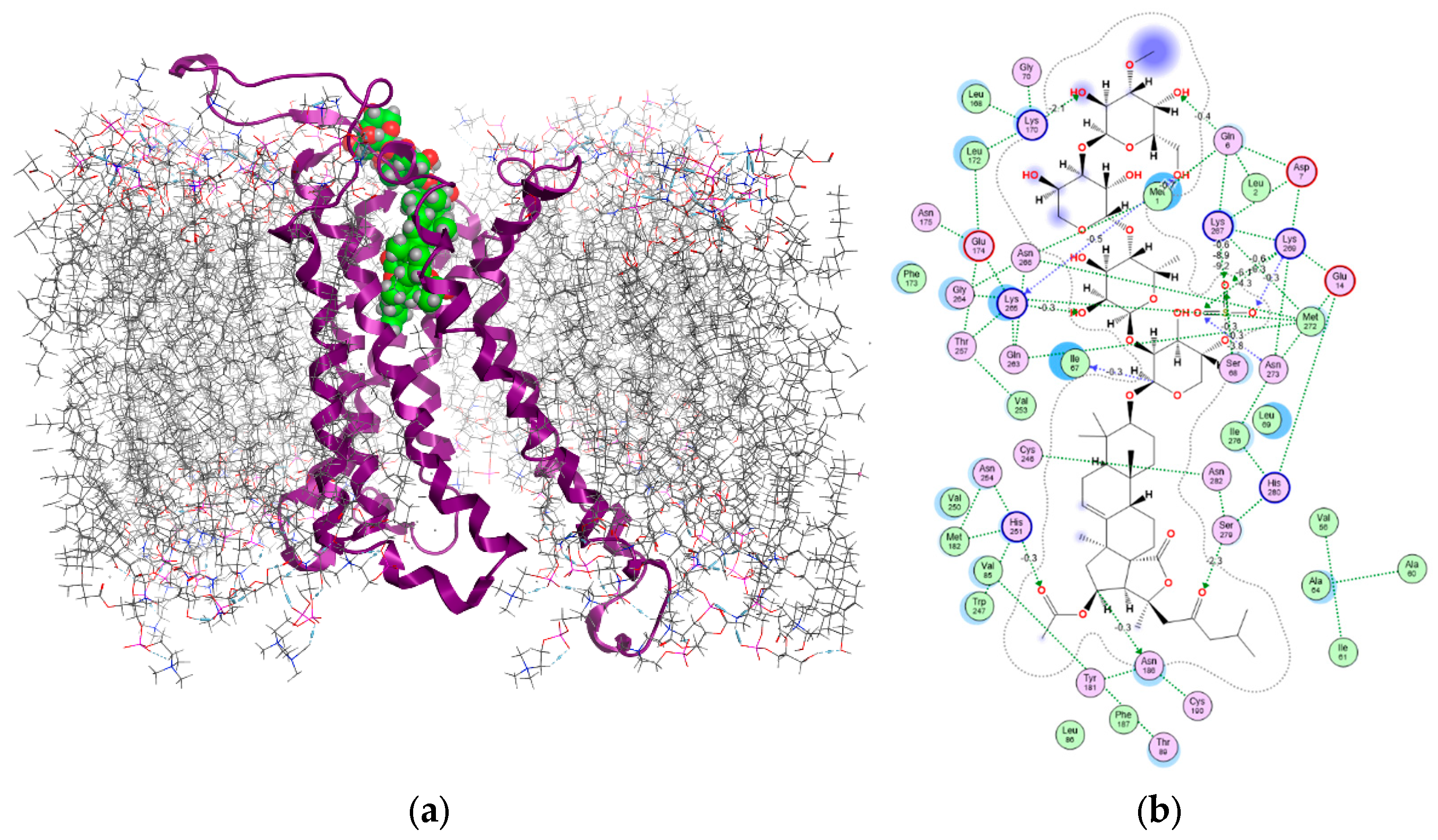

2.3. In Silico Modeling of Okh Binding with A2B Adenosine Receptor (A2BAR)

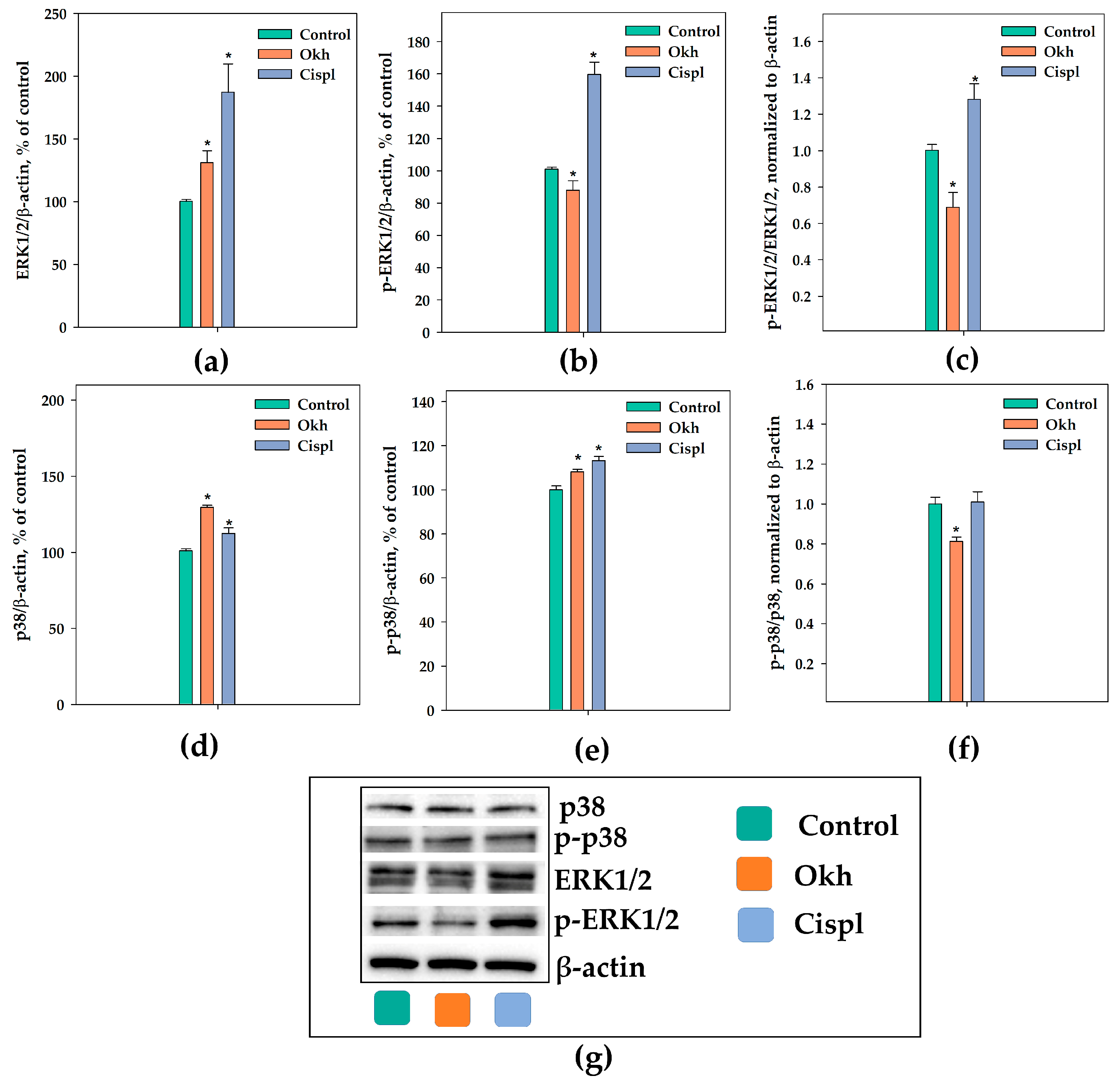

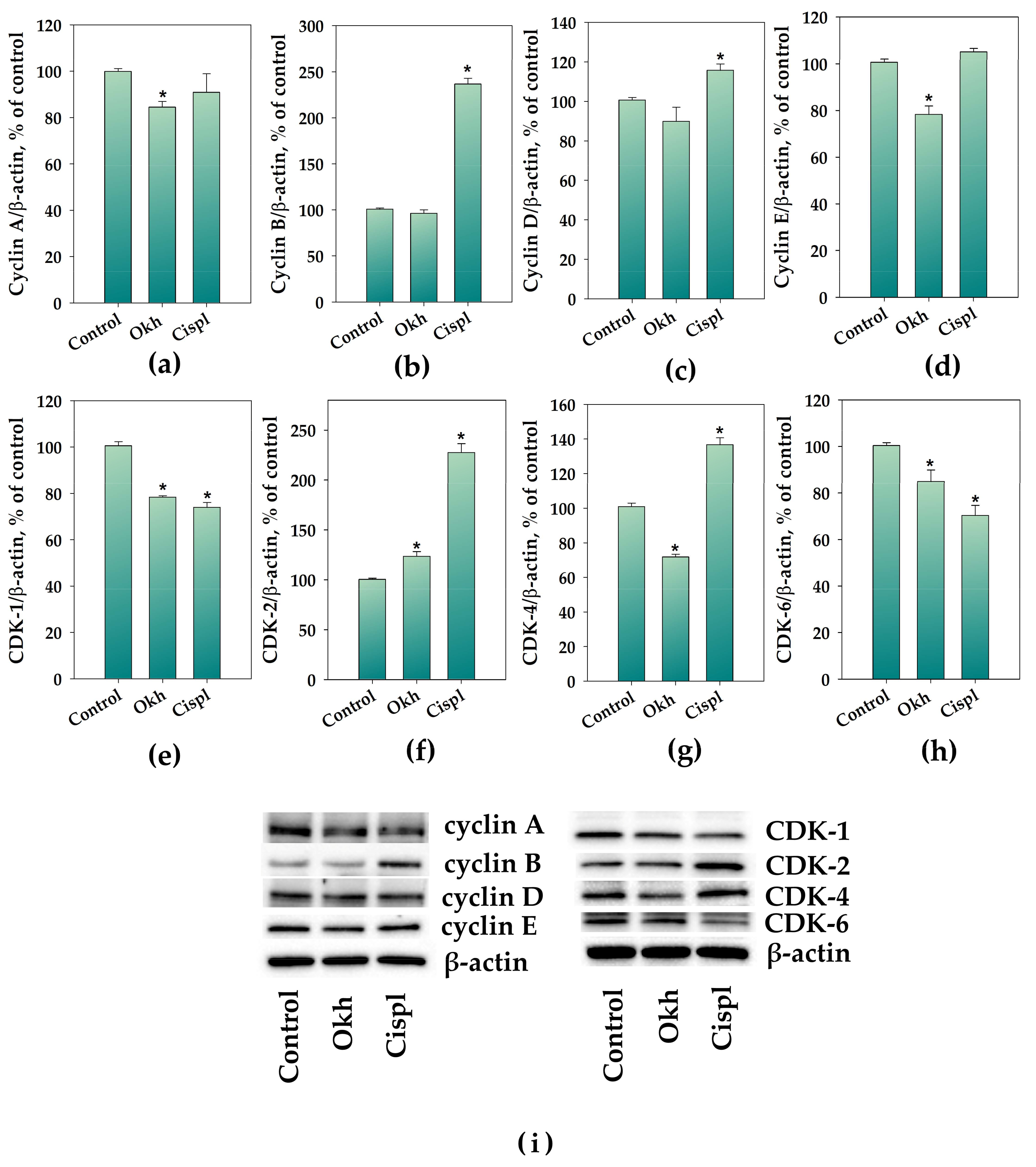

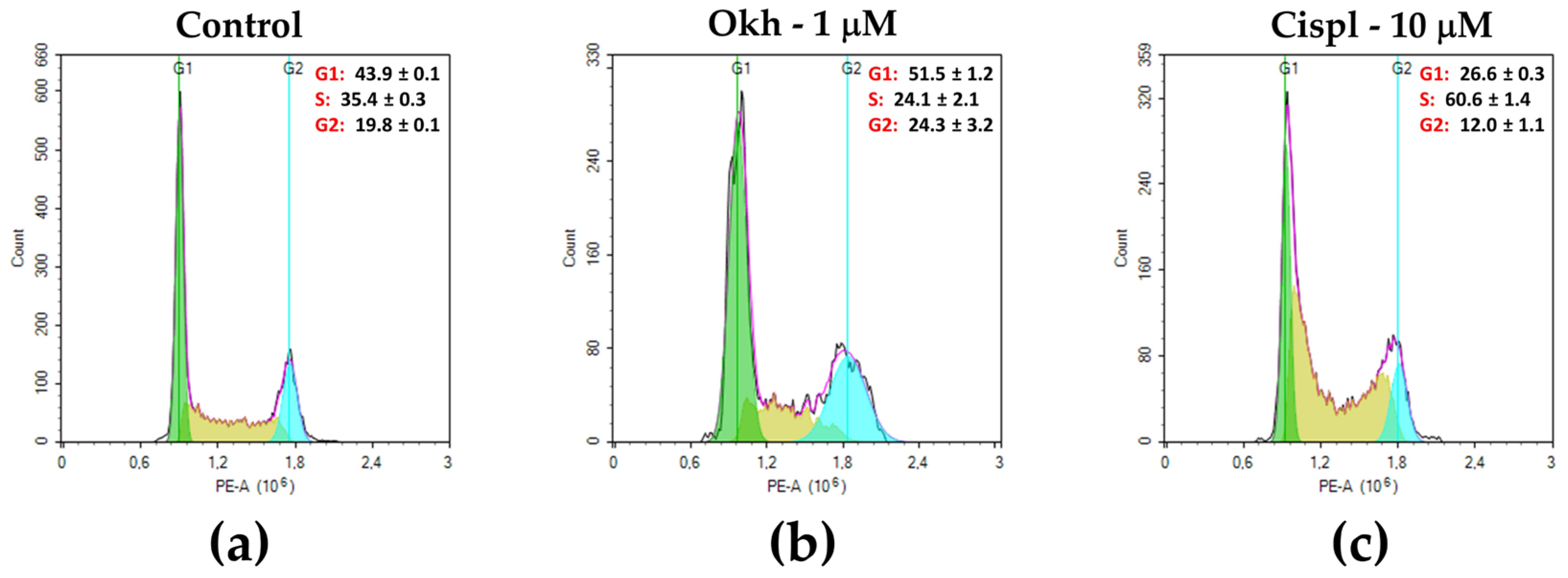

2.4. The Influence of Okh on p38/p-p38, ERK1/2/p-ERK1/2, Cyclins and CDKs Levels, and Cell Cycle Progression in MDA-MB-231 Cells

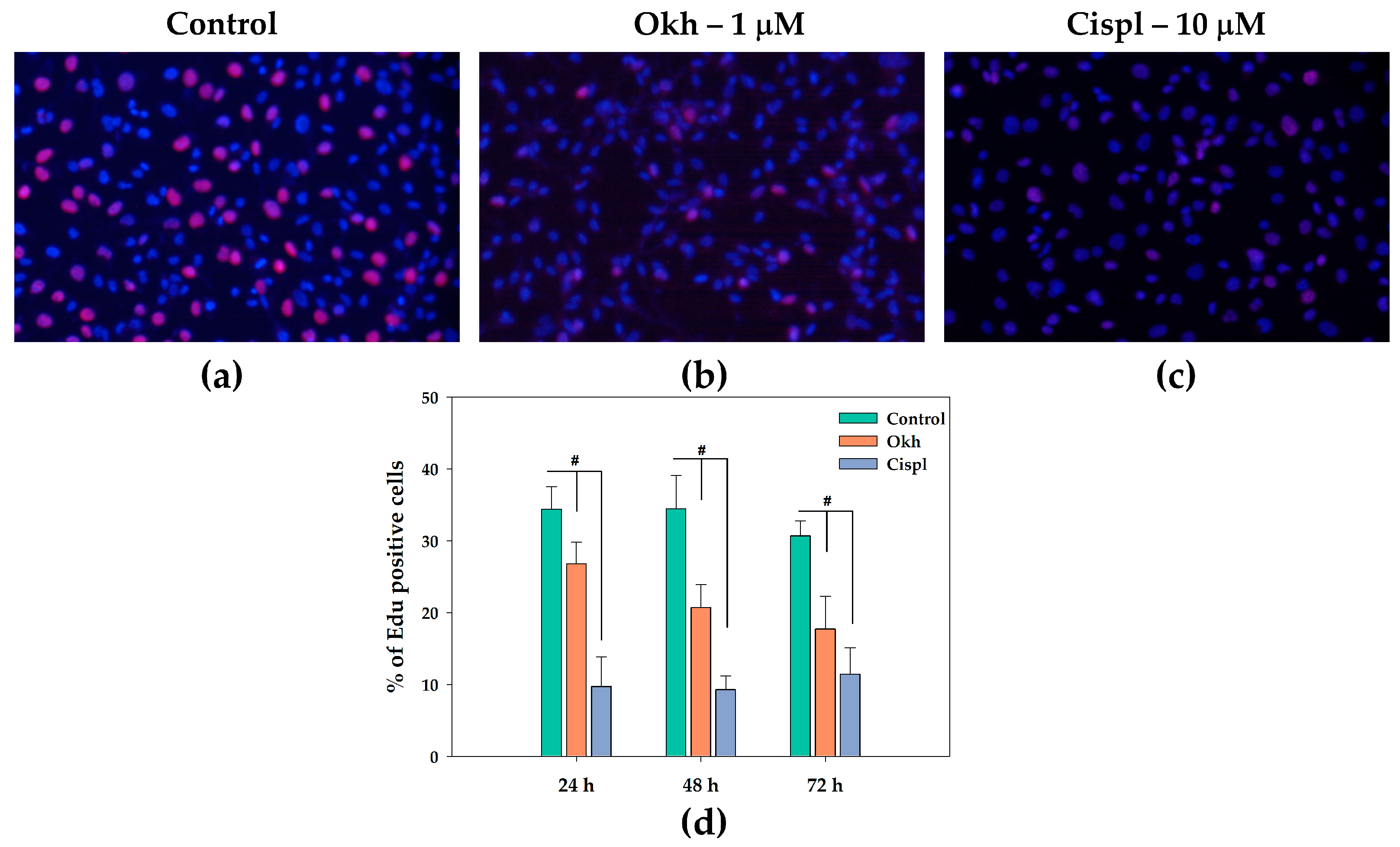

2.5. Effect of Okh on MDA-MB-231 Cell Proliferation in the 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Incorporation Assay

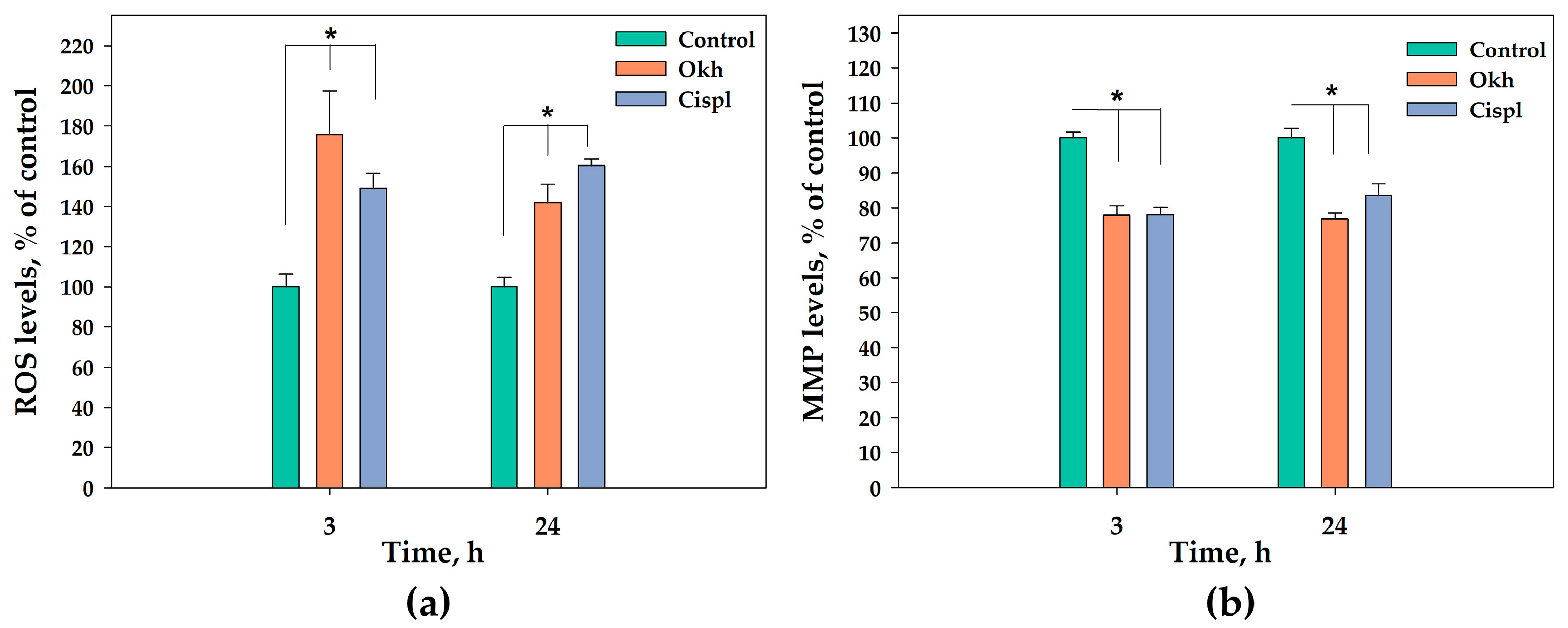

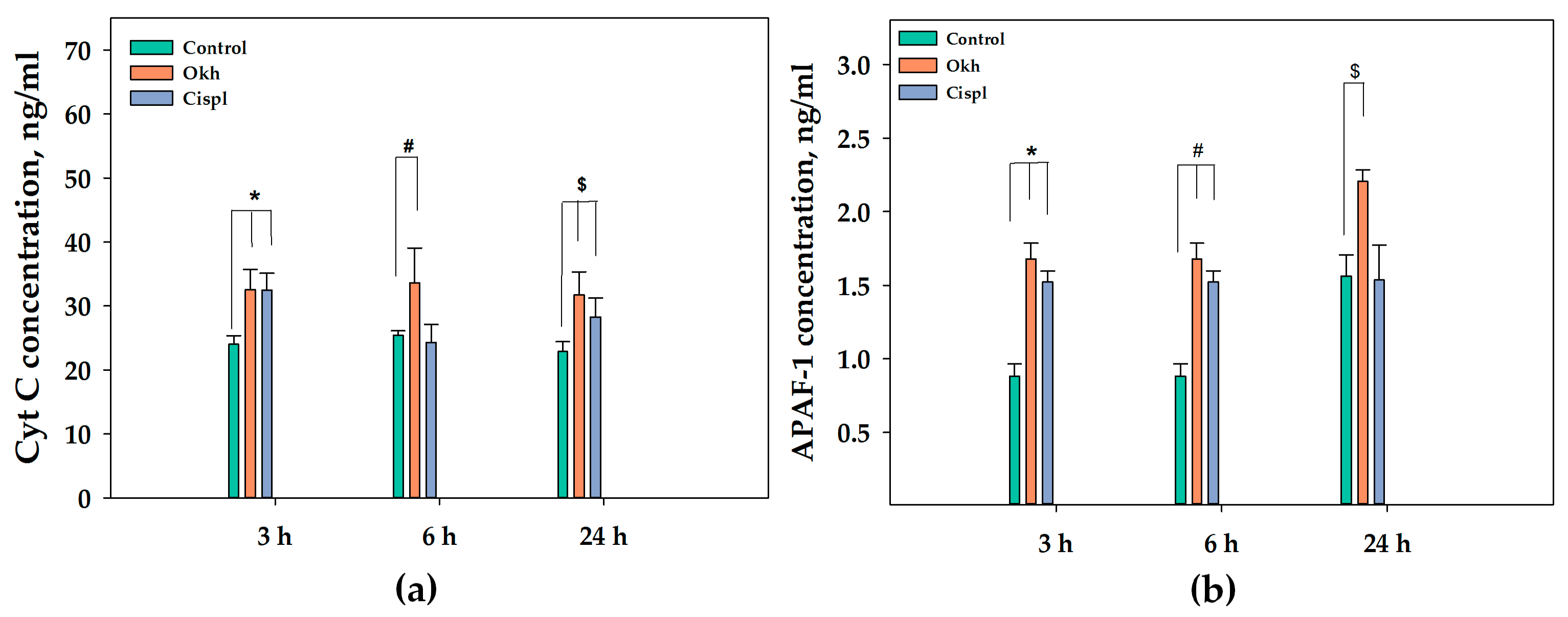

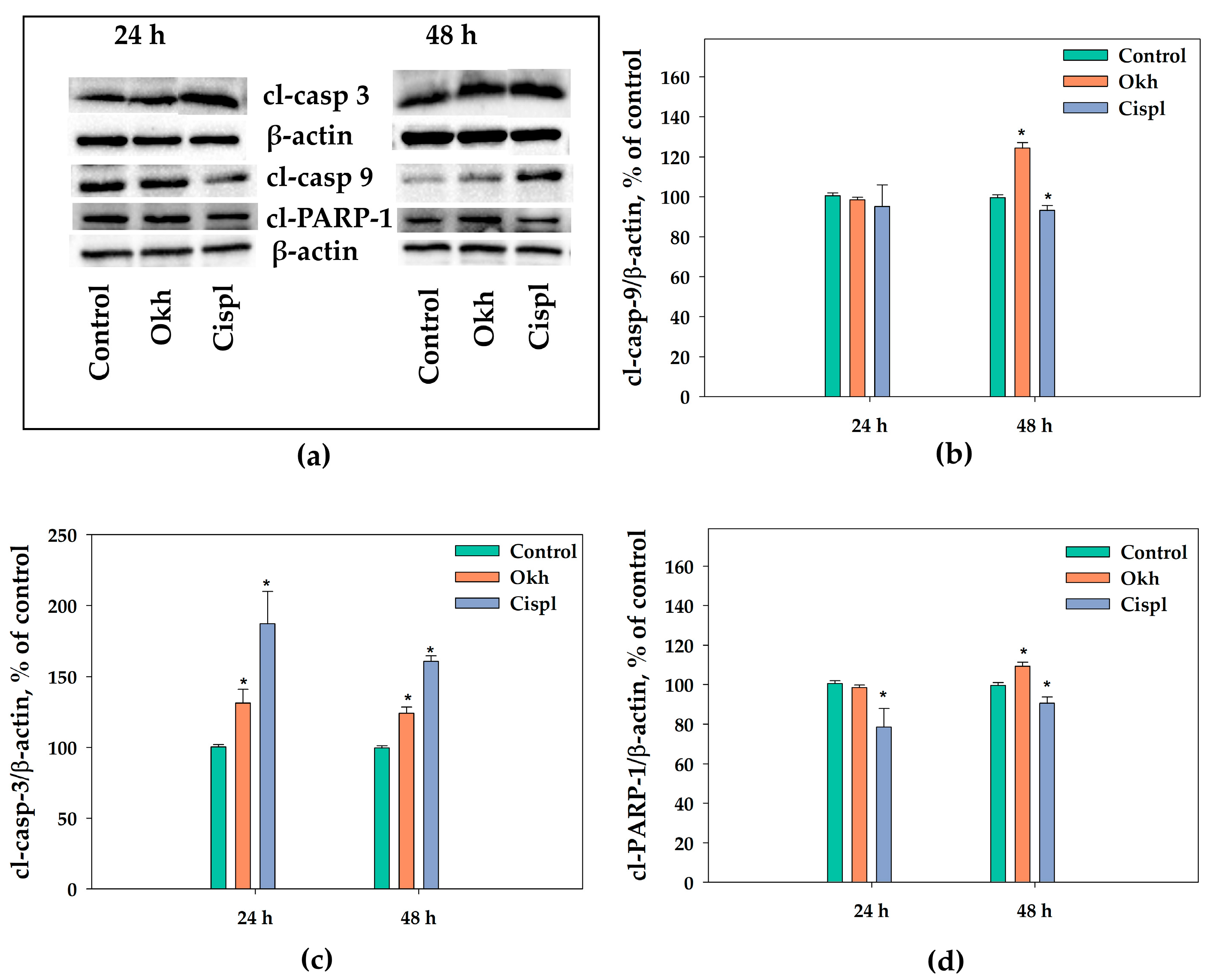

2.6. The Apoptotic Pathway in MDA-MB-231 Cells Induced by Okh

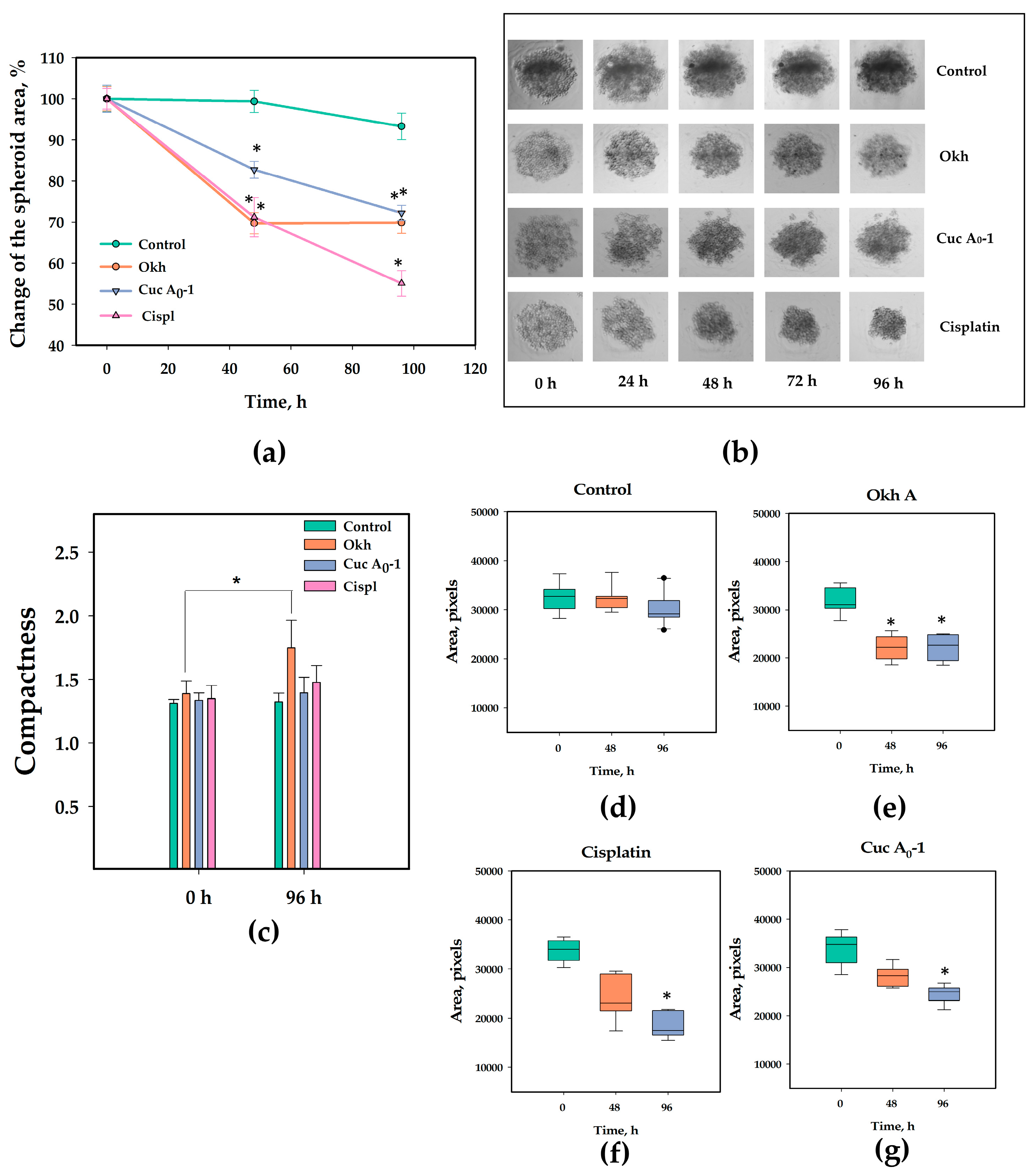

2.7. The Anticancer Effect of Okh in 3D Culture of MDA-MB-231 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Antibodies

4.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

4.3. Analysis of ROS and MMP Levels

4.4. Modeling and Molecular Docking of Okh Binding with A2BAR in Lipid Environment

4.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.6. Calcium Level

4.7. Cell Cycle Analysis

4.8. Western Blotting

4.9. Apoptosis Analysis

4.10. EdU Incorporation Assay

4.11. Cell Counting Assay

4.12. Colony Formation Assay

4.13. Three-Dimensional Culture of MDA-MB-231 Cells

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Harper, A.; McCormack, V.; Sung, H.; Houssami, N.; Morgan, E.; Mutebi, M.; Garvey, G.; Soerjomataram, I.; Fidler-Benaoudia, M.M. Global patterns and trends in breast cancer incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagami, P.; Carey, L.A. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. NPJ Breast Cancer 2022, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattar, A.; Antonini, M.; Amorim, A.G.; Teixeira, M.D.; de Resende, C.A.A.; Cavalcante, F.P.; Zerwes, F.; Arakelian, R.; Millen, E.C.; Brenelli, F.P.; et al. Overall survival and economic impact of triple-negative breast cancer in Brazilian public health care: A real-world study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2025, 11, 2400340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueng, S.H.; Chen, S.C.; Chang, Y.S.; Hsueh, S.; Lin, Y.C.; Chien, H.P.; Lo, Y.F.; Shen, S.C.; Hsueh, C. Phosphorylated mTOR expression correlates with poor outcome in early-stage triple negative breast carcinomas. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2012, 5, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.; Flanagan, L.; Quinn, C.; Evoy, D.; McDermott, E.W.; Pierce, A.; Duffy, M.J. mTOR in breast cancer: Differential expression in triple-negative and non-triple-negative tumors. Breast 2012, 21, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.; Abbas, K.; Alam, M.; Ahmad, W.; Moinuddin; Usmani, N.; Ali Siddiqui, S.; Habib, S. Molecular pathways and therapeutic targets linked to triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Ferre, R.A.; Jonas, S.F.; Salgado, R.; Loi, S.; de Jong, V.; Carter, J.M.; Nielsen, T.O.; Leung, S.; Riaz, N.; Chia, S.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JAMA 2024, 331, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, P.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Su, X.; Han, S.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, C.; Deng, S.; et al. Application of gene editing technology based on targeted delivery materials in TNBC. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 42110–42126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Advances in siRNA drug delivery strategies for targeted TNBC therapy. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, H.E.; Bedair, K.; Hasan, A.; Al-Mansoori, L.; Caratelli, S.; Sconocchia, G.; Gaiba, A.; Cenciarelli, C. Current status and innovative developments of CAR-T-cell therapy for the treatment of breast cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, A.; Vidula, N.; Ellisen, L.; Bardia, A. Novel antibody-drug conjugates for triple negative breast cancer. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2020, 12, 1758835920915980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjehpour, M.; Castro, M.; Klotz, K.N. The human breast cell line MDA-MB-231 expresses endogenous A2B adenosine receptors mediating a Ca2+ signal. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 155, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Lu, H.; Samanta, D.; Salman, S.; Lu, Y.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent expression of adenosine receptor 2B promotes breast cancer stem cell enrichment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E9640–E9648, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA2022, 119, e2210925119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasama, H.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kasamatsu, A.; Okamoto, A.; Koyama, T.; Minakawa, Y.; Ogawara, K.; Yokoe, H.; Shiiba, M.; Tanzawa, H.; et al. Adenosine A2B receptor promotes progression of human oral cancer. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.; Palomo, I.; Fuentes, E. Role of adenosine A2B receptor overexpression in tumor progression. Life Sci. 2016, 166, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chu, X.; Deng, F.; Tong, L.; Tong, G.; Yi, Y.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Tang, Y.; Xia, Y.; et al. The adenosine A2B receptor promotes tumor progression of bladder urothelial carcinoma by enhancing MAPK signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 48755–48768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.-G.; Jacobson, K.A. A2B adenosine receptor and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherne, C.M.; Kewley, E.M.; Eltzschig, H.K. The resurgence of A2B adenosine receptor signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2011, 1808, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.G.; Gao, R.R.; Meyer, C.K.; Jacobson, K.A. A2B adenosine receptor-triggered intracellular calcium mobilization: Cell type-dependent involvement of Gi, Gq, Gs proteins and protein kinase C. Purinergic Signal. 2025, 21, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkat, M.; Bast, H.; Drees, R.; Dünser, J.; Mahr, A.; Azoitei, N.; Marienfeld, R.; Frank, F.; Brhel, M.; Ushmorov, A.; et al. Adenosine receptor 2B activity promotes autonomous growth, migration as well as vascularization of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Meng, Z. Expression and gene regulation network of adenosine receptor A2B in lung adenocarcinoma: A potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 663011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, C.A.; Levine, K.; Oesterreich, S. Targeting adenosine receptor 2B in triple negative breast cancer. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2018, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelepuga, E.A.; Chingizova, E.A.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Avilov, S.A.; Kalinin, V.I.; Aminin, D.L.; Silchenko, A.S. Anticancer activity of triterpene glycosides cucumarioside A0-1 and djakonovioside A against MDA-MB-231 as A2B adenosine receptor antagonists. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silchenko, A.S.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Avilov, S.A.; Popov, R.S.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Chingizova, E.A.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Panina, E.G.; Stepanov, V.G.; Kalinin, V.I.; et al. Djakonoviosides A, A1, A2, B1–B4—Triterpene monosulfated tetra- and pentaosides from the sea cucumber Cucumaria djakonovi: The first finding of a hemiketal fragment in the aglycones; activity against human breast cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menchinskaya, E.S.; Chingizova, E.A.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Klimovich, A.A.; Zelepuga, E.A.; Aminin, D.L.; Avilov, S.A.; Silchenko, A.S. Mechanisms of action of sea cucumber triterpene glycosides cucumarioside A0-1 and djakonovioside A against human triple-negative breast cancer. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silchenko, A.S.; Chingizova, E.A.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Zelepuga, E.A.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Avilov, S.A.; Tabakmakher, K.M.; Popov, R.S.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Dautov, S.S.; et al. Composition of triterpene glycosides of the Far Eastern sea cucumber Cucumaria conicospermium Levin et Stepanov; structure elucidation of five minor conicospermiumosides A3-1, A3-2, A3-3, A7-1, and A7-2; cytotoxicity of the glycosides against human breast cancer cell lines; structure–activity relationships. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiedel, A.C.; Lacher, S.K.; Linnemann, C.; Knolle, P.A.; Müller, C.E. Antiproliferative effects of selective adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists on human lymphocytes: Evidence for receptor-independent mechanisms. Purinergic Signal. 2013, 9, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Xu, Y.; Guo, S.; He, X.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Yin, W.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, H.; et al. Structures of adenosine receptor A2BAR bound to endogenous and synthetic agonists. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, T.; Iyer, V.G.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI: A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 11, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Ingólfsson, H.I.; Cheng, X.; Lee, J.; Marrink, S.J.; Im, W. CHARMM-GUI Martini Maker for Coarse-Grained Simulations with the Martini Force Field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 4486–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keränen, H.; Gutiérrez-de-Terán, H.; Aqvist, J. Structural and energetic effects of A2A adenosine receptor mutations on agonist and antagonist binding. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 108492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimm, D.; Schiedel, A.C.; Sherbiny, F.F.; Hinz, S.; Hochheiser, K.; Bertarelli, D.C.; Maass, A.; Müller, C.E. Ligand-specific binding and activation of the human adenosine A(2B) receptor. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Ben, D.; Buccioni, M.; Lambertucci, C.; Thomas, A.; Volpini, R. Simulation and comparative analysis of binding modes of nucleoside and non-nucleoside agonists at the A2B adenosine receptor. In Silico Pharmacol. 2013, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, M.; Fassihi, A.; Saghaie, L.; Madadkar-Sobhani, A.; Mahnam, K.; Abbasi, M. QSAR and docking analysis of A2B adenosine receptor antagonists based on non-xanthine scaffold. Med. Chem. Res. 2015, 24, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherbiny, F.F.; Schiedel, A.C.; Maass, A.; Müller, C.E. Homology modelling of the human adenosine A2B receptor based on X-ray structures of bovine rhodopsin, the β2-adrenergic receptor and the human adenosine A2A receptor. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2009, 23, 807–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beerkens, B.L.H.; Wang, X.; Avgeropoulou, M.; Adistia, L.N.; van Veldhoven, J.P.D.; Jespers, W.; Liu, R.; Heitman, L.H.; IJzerman, A.P.; van der Es, D. Development of Subtype-Selective Covalent Ligands for the Adenosine A2B Receptor by Tuning the Reactive Group. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 13, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temirak, A.; Schlegel, J.G.; Voss, J.H.; Vaaßen, V.J.; Vielmuth, C.; Claff, T.; Müller, C.E. Irreversible Antagonists for the Adenosine A2B Receptor. Molecules 2022, 27, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beerkens, B.L.H.; Andrianopoulou, V.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; van Westen, G.J.P.; Jespers, W.; IJzerman, A.P.; Heitman, L.H.; van der Es, D. N-Acyl-N-Alkyl Sulfonamide Probes for Ligand-Directed Covalent Labeling of GPCRs: The Adenosine A2B Receptor as Case Study. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024, 19, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.T.; Lee, N.K. A2B adenosine receptor stimulation down-regulates M-CSF-mediated osteoclast proliferation. Biomed. Sci. Lett. 2017, 23, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chu, X.; Yi, Y.; Hao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Yuxin, T.; Dai, Y. MRS1754 inhibits proliferation and migration of bladder urothelial carcinoma by regulating mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 11360–11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Lérida, I.; Aragay, A.M.; Asensio, A.; Ribas, C. Gq signaling in autophagy control: Between chemical and mechanical cues. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, E.; Pulicati, A.; Cencioni, M.T.; Cozzolino, M.; Navoni, F.; di Martino, S.; Nardacci, R.; Carrì, M.T.; Cecconi, F. Apoptosome-deficient cells lose cytochrome c through proteasomal degradation but survive by autophagy-dependent glycolysis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 3576–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.M.; Oleinick, N.L. Dissociation of mitochondrial depolarization from cytochrome c release during apoptosis induced by photodynamic therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 84, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walzl, A.; Unger, C.; Kramer, N.; Unterleuthner, D.; Scherzer, M.; Hengstschläger, M.; Schwanzer-Pfeiffer, D.; Dolznig, H. The resazurin reduction assay can distinguish cytotoxic from cytostatic compounds in spheroid screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 2014, 19, 1047–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandarić, T.; Gutiérrez-de-Terán, H. Ligand and Residue Free Energy Perturbations Solve the Dual Binding Mode Proposal for an A2BAR Partial Agonist. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, A.; Evangelisti, C.; Cappellini, A.; Mongiorgi, S.; Koufi, F.-D.; Neri, I.; Marvi, M.V.; Russo, M.; Ghigo, A.; Manzoli, L.; et al. Emerging roles of phospholipase C beta isozymes as potential biomarkers in cardiac disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meij, J.T.; Suzuki, S.; Panagia, V.; Dhalla, N.S. Oxidative stress modifies the activity of cardiac sarcolemmal phospholipase C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1994, 1199, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, W.; Huang, B.; Zhang, S.; Miao, J. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C and ROS were involved in chicken blastodisc differentiation to vascular endothelial cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007, 102, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoguchi, T.; Sonta, T.; Tsubouchi, H.; Etoh, T.; Kakimoto, M.; Sonoda, N.; Sato, N.; Sekiguchi, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Sumimoto, H.; et al. Protein kinase C-dependent increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in vascular tissues of diabetes: Role of vascular NAD(P)H oxidase. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003, 14, S227–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Xu, L.; Guo, M. The role of protein kinase C in diabetic microvascular complications. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 973058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalpando-Rodriguez, G.E.; Gibson, S.B. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulates different types of cell death by acting as a rheostat. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9912436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfin, S.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Kesari, K.K.; Ruokolainen, J.; Roychoudhury, S.; Rathi, B.; Kumar, D. Oxidative stress in cancer cell metabolism. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowe, D.F.; Camara, A.K. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: Modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 1373–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Xiao, Z.; Ko, H.L.; Ren, E.C. The p53 response element and transcriptional repression. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Guerrero, G.; Umbaugh, D.S.; Ramachandran, A.A.; Artigues, A.; Jaeschke, H.; Ramachandran, A. Translocation of adenosine A2B receptor to mitochondria influences cytochrome P450 2E1 activity after acetaminophen overdose. Livers 2024, 4, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, T.; Noda, Y.; Tanaka, K.I.; Yamakawa, N.; Wada, M.; Mashimo, T.; Fukunishi, Y.; Mizushima, T.; Takenaga, M. A2B adenosine receptor inhibition by the dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker nifedipine involves colonic fluid secretion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baev, A.Y.; Vinokurov, A.Y.; Potapova, E.V.; Dunaev, A.V.; Angelova, P.R.; Abramov, A.Y. Mitochondrial permeability transition, cell death and neurodegeneration. Cells 2024, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, B. Cytochrome c and cancer cell metabolism: A new perspective. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Nijhawan, D.; Budihardjo, I.; Srinivasula, S.M.; Ahmad, M.; Alnemri, E.S.; Wang, X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell 1997, 91, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Yang, J.; Jones, D.P. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis: The role of cytochrome C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1998, 1366, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Hauschild, J.; Kriegs, M.; Hoffer, K.; Burenina, O.Y.; Strewinsky, N.; Malyarenko, T.V.; Kicha, A.A.; Ivanchina, N.V.; Stonik, V.A.; et al. Anticancer activity of triterpene glycosides from the sea star Solaster pacificus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Iguchi, T.; Kuroda, M.; Mishima, M.; Mimaki, Y. Novel oleanane-type triterpene glycosides from the Saponaria officinalis L. seeds and apoptosis-inducing activity via mitochondria. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloche, S.; Pouysségur, J. The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3227–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bitar, S.; Gali-Muhtasib, H. The role of the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21cip1/waf1 in targeting cancer: Molecular mechanisms and novel therapeutics. Cancers 2019, 11, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Dutta, A. p21 in cancer: Intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, R.; Satoh, R.; Takasaki, T. ERK: A double-edged sword in cancer. ERK-dependent apoptosis as a potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Lee, M.; Cha, E.; Sul, J.; Park, J.; Lee, J. Eribulin mesylate improves cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity of triple-negative breast cancer by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation. Medicina 2022, 58, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Karami-Tehrani, F.; Panjehpour, M.; Salami, S.; Fallahian, F. Adenosine induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in androgen-dependent and -independent prostate cancer cell lines, LNcap-FGC-10, DU-145, and PC3. Prostate 2012, 72, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirali, S.; Aghaei, M.; Shabani, M.; Fathi, M.; Sohrabi, M.; Moeinifard, M. Adenosine induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis via cyclinD1/Cdk4 and Bcl-2/Bax pathways in human ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR-3. Tumour Biol. 2013, 34, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.M.; Joshaghani, H.R.; Panjehpour, M.; Aghaei, M. A2B adenosine receptor agonist induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in breast cancer stem cells via ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Cell. Oncol. 2018, 41, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Pang, K.L.; Chen, S.J.; Yang, D.; Nai, A.T.; He, G.C.; Fang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Cai, M.B.; He, J.Y. ADORA2B promotes proliferation and migration in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and is associated with immune infiltration. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, L.N.; Faraoni, E.Y.; Ruan, W.; Yuan, X.; Eltzschig, H.K.; Bailey-Lundberg, J.M. The resurgence of the Adora2b receptor as an immunotherapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1163585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Akdemir, I.; Fan, J.; Linden, J.; Zhang, B.; Cekic, C. The expression of adenosine A2B receptor on antigen-presenting cells suppresses CD8+ T-cell responses and promotes tumor growth. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, L.; Salkeni, M.A.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Grewal, J.S.; Tester, W.J.; Pachynski, R.K.; Frigo, D.; Panaretakis, T.; Pastore, D.R.E.; Kramer, R.A.; et al. ADPORT-601: First-in-human study of adenosine 2A (A2A) and adenosine 2B (A2B) receptor antagonists in patients with select advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminin, D.L.; Chaykina, E.L.; Agafonova, I.G.; Avilov, S.A.; Kalinin, V.I.; Stonik, V.A. Antitumor activity of the immunomodulatory lead Cumaside. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminin, D. Immunomodulatory properties of sea cucumber triterpene glycosides. In Marine and Freshwater Toxins; Gopalkrishnakone, P., Haddad, V., Jr., Tubaro, A., Kim, E., Kem, W., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 381–401. [Google Scholar]

- Aminin, D.; Pisliagin, E.; Astashev, M.; Es’kov, A.; Kozhemyako, V.; Avilov, S.; Zelepuga, E.; Yurchenko, E.; Kaluzhskiy, L.; Kozlovskaya, E.; et al. Glycosides from edible sea cucumbers stimulate macrophages via purinergic receptors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE); Version 2019.01; Chemical Computing Group ULC: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2021.

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Babin, V.; Berryman, J.T.; Betz, R.M.; Cai, Q.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Darden, T.A.; Duke, R.E.; Gohlke, H.; et al. AMBER 14; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, C.J.; Madej, B.D.; Skjevik, A.A.; Betz, R.M.; Teigen, K.; Gould, I.R.; Walker, R.C. Lipid14: The amber lipid force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 865–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, D.R.; Swain-Bowden, M.J.; Lucas, A.M.; Carpenter, A.E.; Cimini, B.A.; Goodman, A. CellProfiler 4: Improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Formazan Production, % of Untreated Cells |

|---|---|

| Untreated cells | 100.0 ± 8.2 |

| Okh (1 µM) | 85.3 ± 6.3 * |

| Cuc A0-1 (1 µM) | 96.9 ± 11.8 |

| Cispl (10 µM) | 83.9 ± 1.7 * |

| Okh | ΔSASAL, Å2 | ΔSASAR, Å2 | Scompl | Ecompl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| binding mode A | 888.3 | 1117.2 | 0.7 | −0.62 |

| binding mode B | 630.5 | 739 | 0.63 | −0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chingizova, E.A.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Zelepuga, E.A.; Pislyagin, E.A.; Nesterenko, L.E.; Avilov, S.A.; Kalinin, V.I.; Aminin, D.L.; Silchenko, A.S. A2BAR-Mediated Antiproliferative and Anticancer Effects of Okhotoside A1-1 in Monolayer and 3D Culture of Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120456

Chingizova EA, Menchinskaya ES, Yurchenko EA, Zelepuga EA, Pislyagin EA, Nesterenko LE, Avilov SA, Kalinin VI, Aminin DL, Silchenko AS. A2BAR-Mediated Antiproliferative and Anticancer Effects of Okhotoside A1-1 in Monolayer and 3D Culture of Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(12):456. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120456

Chicago/Turabian StyleChingizova, Ekaterina A., Ekaterina S. Menchinskaya, Ekaterina A. Yurchenko, Elena A. Zelepuga, Evgeny A. Pislyagin, Liliana E. Nesterenko, Sergey A. Avilov, Vladimir I. Kalinin, Dmitry L. Aminin, and Alexandra S. Silchenko. 2025. "A2BAR-Mediated Antiproliferative and Anticancer Effects of Okhotoside A1-1 in Monolayer and 3D Culture of Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells" Marine Drugs 23, no. 12: 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120456

APA StyleChingizova, E. A., Menchinskaya, E. S., Yurchenko, E. A., Zelepuga, E. A., Pislyagin, E. A., Nesterenko, L. E., Avilov, S. A., Kalinin, V. I., Aminin, D. L., & Silchenko, A. S. (2025). A2BAR-Mediated Antiproliferative and Anticancer Effects of Okhotoside A1-1 in Monolayer and 3D Culture of Human Breast Cancer MDA-MB-231 Cells. Marine Drugs, 23(12), 456. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23120456