Two New Chromone Derivatives from a Marine Algicolous Fungus Aspergillus versicolor GXIMD 02518 and Their Osteoclastogenesis Inhibitory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

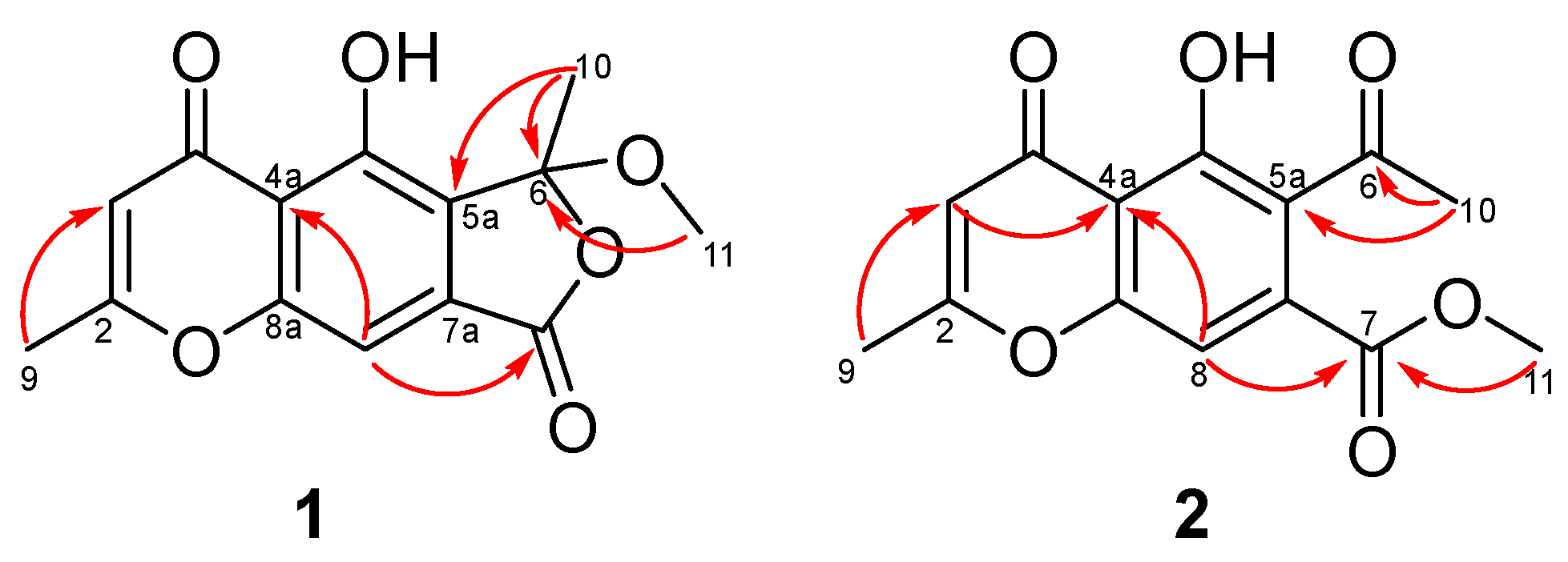

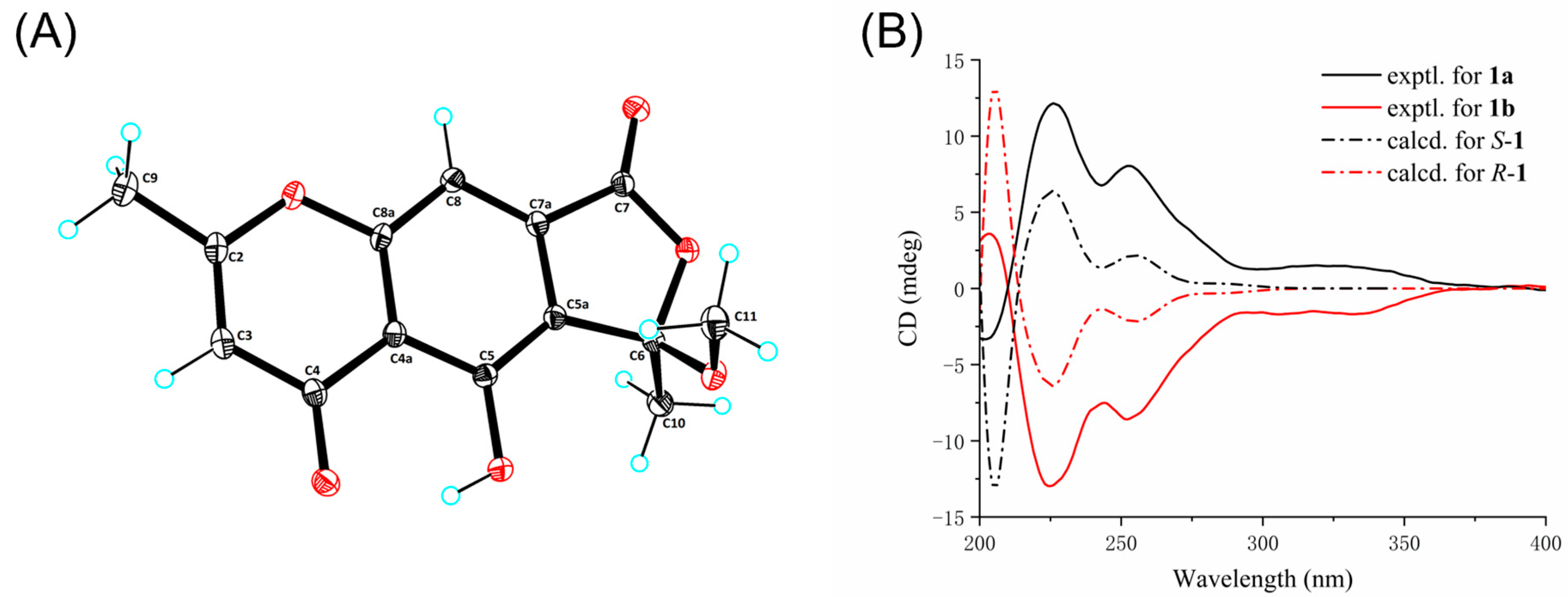

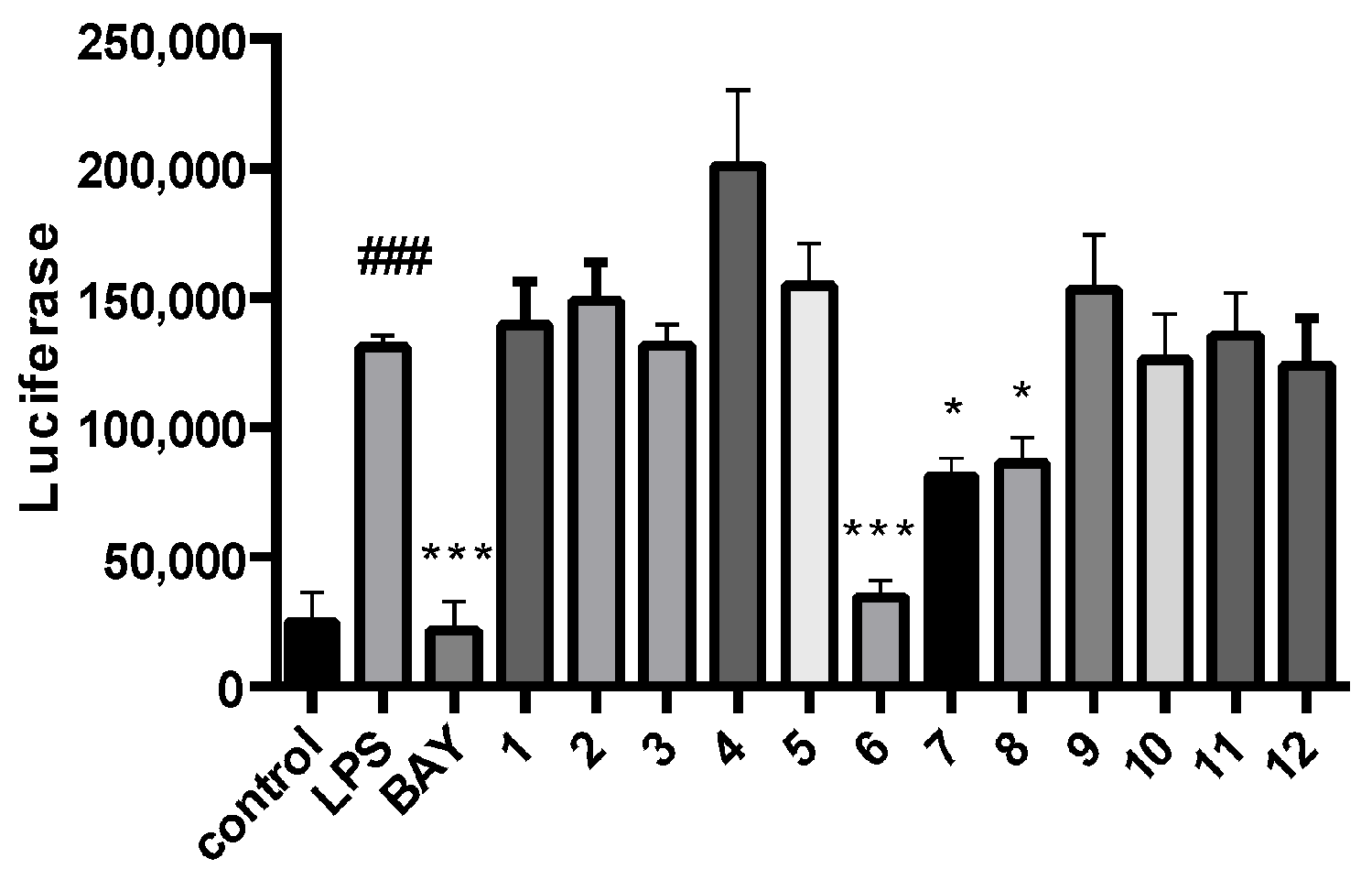

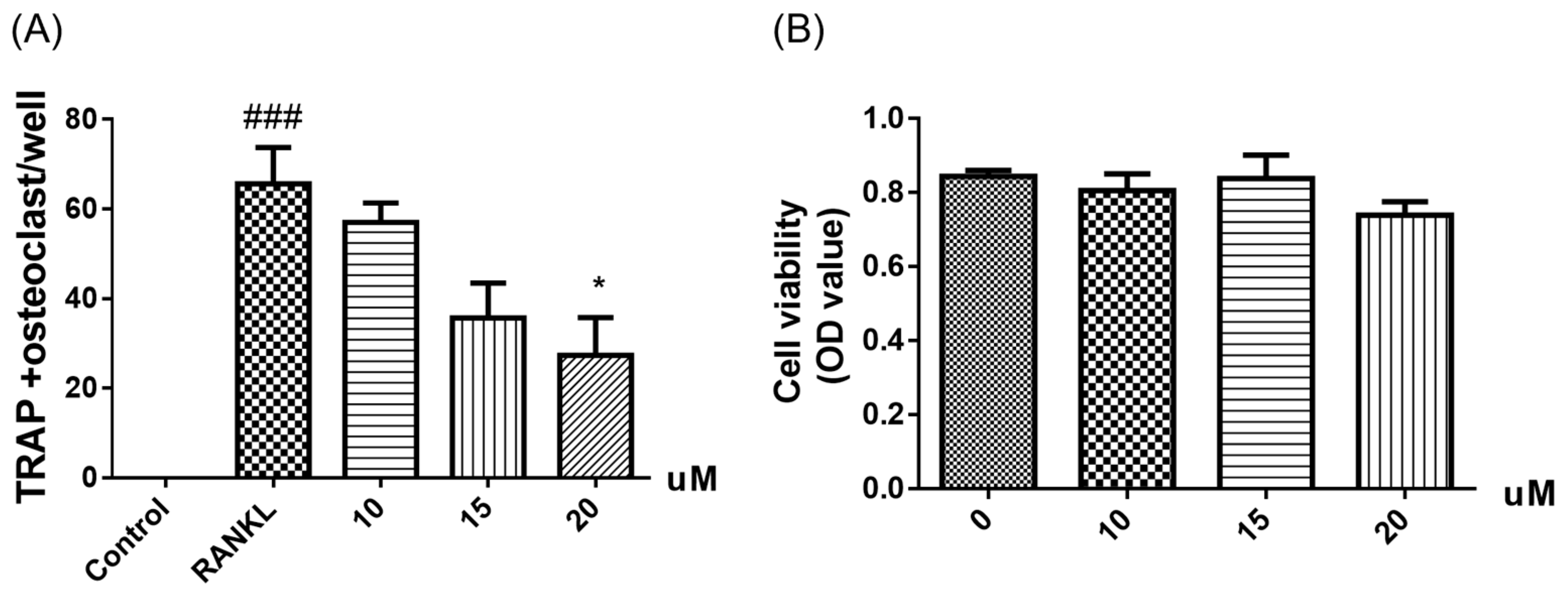

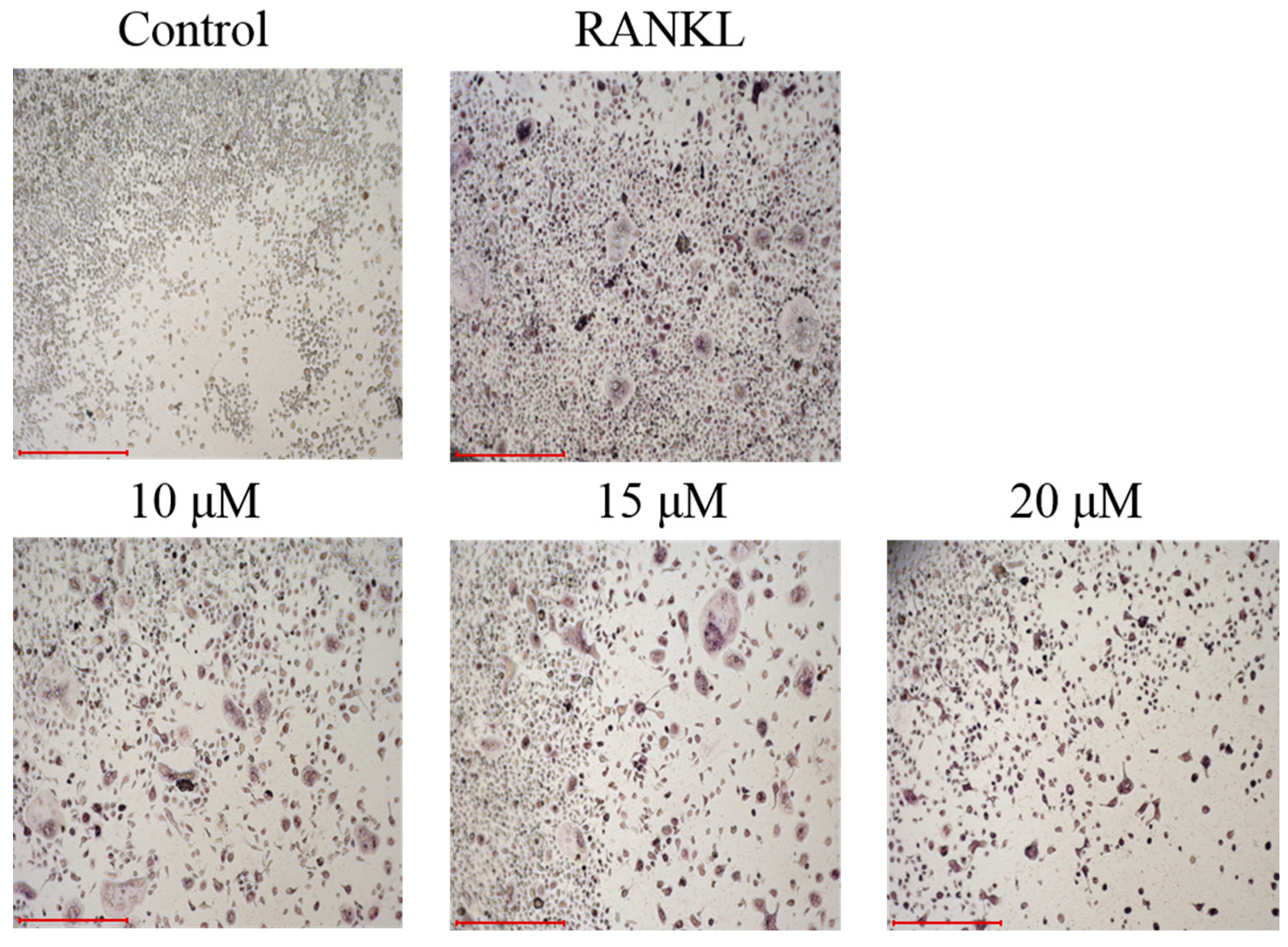

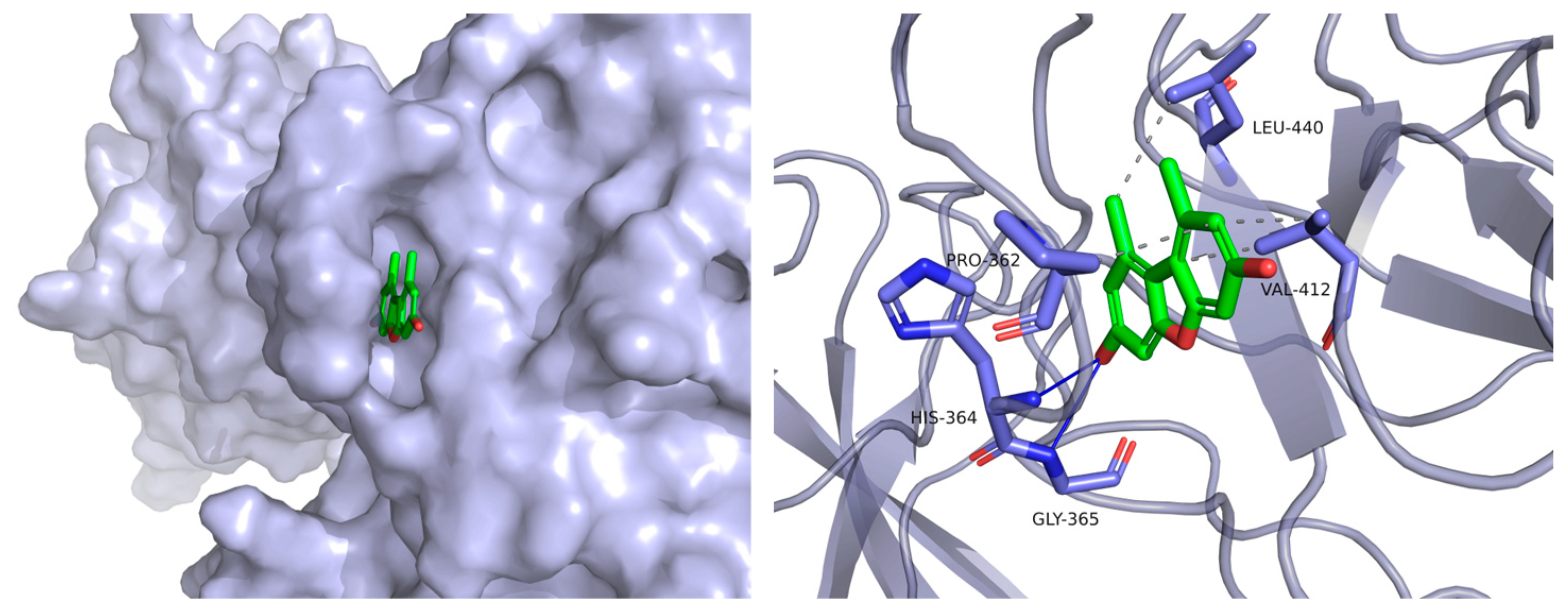

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.2. Fungal Strain and Fermentation

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

3.4. ECD Calculation of Compound 1

3.5. Crystallographic Data for Compound 1

3.6. Anti-Osteoclastogenic Assay

3.7. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodan, G.A.; Martin, T.J. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science 2000, 289, 1508–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.R.; Li, S.X.; Luo, H.Y.; Li, J.N.; Wang, T.; Han, X.Z. The crucial role of SPP1 in osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and cancer. Pharm. Sci. Adv. 2025, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.J.; Huang, K.S.; Hu, J.L. Potential of Panax ginseng for bone health and osteoporosis management. Chin. Herb. Med. 2025, 17, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compston, J.E.; McClung, M.R.; Leslie, W.D. Osteoporosis. Lancet 2019, 393, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheer, S.M.; Noble, S. Zoledronic Acid. Drugs 2001, 61, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sølling, A.S.; Tsourdi, E.; Harsløf, T.; Langdahl, B.L. Denosumab discontinuation. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2023, 21, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegen, S.; Moermans, K.; Stockmans, I.; Thienpont, B.; Carmeliet, G. The serine synthesis pathway drives osteoclast differentiation through epigenetic regulation of NFATc1 expression. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.H.; Deng, W.D.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Ke, M.H.; Zou, B.H.; Luo, X.W.; Su, J.B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Xu, J.L.; Nandakumar, K.S.; et al. A marine fungus-derived nitrobenzoyl sesquiterpenoid suppresses receptor activator of NF-κB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis and inflammatory bone destruction. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 4242–4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.P.; Tan, Y.H.; Lu, H.M.; Feng, Y.Y.; Li, M.; Gao, C.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Luo, X.W. Azaphilone derivatives with RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis inhibition from the mangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2025, 23, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Li, R.F.; Lin, M.P.; Chen, C.M.; Qi, X.; Zhou, X.F.; Liu, Y.H.; Tan, Y.H.; Luo, X.W. Antiosteoclastogenic indole alkaloids from the mangrove endophytic fungus Penicillium brefeldianum GXIMD 02511. J. Nat. Prod. 2025, 88, 1671–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Li, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.T.; Chen, C.M.; Chen, W.H.; Gao, C.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Tan, Y.H.; Luo, X.W. A new α-cyclopiazonic acid alkaloid identified from the Weizhou Island coral-derived fungus Aspergillus flavus GXIMD 02503. J. Ocean Univ. China 2022, 21, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Li, Z.C.; Huang, B.Y.; Liu, K.; Peng, S.; Liu, X.M.; Gao, C.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Tan, Y.H.; Luo, X.W. Anti-Osteoclastogenic and antibacterial effects of chlorinated polyketides from the Beibu Gulf coral-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis GXIMD 02505. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.M.; Xiao, L.X.; Luo, X.W.; Cai, J.; Huang, L.S.; Tao, H.M.; Zhou, X.F.; Tan, Y.H.; Liu, Y.H. Identifying marine-derived tanzawaic acid derivatives as novel inhibitors against osteoclastogenesis and osteoporosis via downregulation of NF-κB and NFATc1 activation. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 2602–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Li, M.; Xiao, L.X.; Zheng, X.; Li, R.; Dong, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Wen, H.Y.; Ruan, K.L.; Cheng, K.G.; et al. 6-O-angeloylplenolin inhibits osteoclastogenesis in vitro via suppressing c-Src/NF-κB/NFATc1 pathways and ameliorates bone resorption in collagen-induced arthritis mouse model. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 224, 116230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intaraudom, C.; Bunbamrung, N.; Dramae, A.; Boonyuen, N.; Choowong, W.; Rachtawee, P.; Pittayakhajonwut, P. Chromone derivatives, R- and S-taeniolin, from the marine-derived fungus Taeniolella sp. BCC31839. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, K.; Kawanishi, H.; Taniguchi, M.; Kozawa, M. Chromones from Cnidium Monnieri. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Lin, C.H.; Kuo, C.C.; Wu, M.D.; Cheng, M.J.; Chen, J.J.; Chao, C.Y.; Huang, G.J.; Kuo, Y.H. Two new chromones and a new coumarin from the fruit of Cnidium Monnieri (L.) Cusson. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.M.; Yang, D.; Adhikari, A.; Ye, F.; Zheng, C.J.; Yan, W.; Meng, S.; Su, P.; Shen, B. Neogrisemycin, a trisulfide-bridged angucycline, produced upon expressing the thioangucycline biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces Albus J1074. Org. Lett. 2023, 25, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, A.N.; Smetanina, O.F.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Pivkin, M.V.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Kuznetsova, T.A. A new meroterpenoid from the marine fungus Aspergillus versicolor (Vuill.) Tirab. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2010, 59, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Mou, Y.H.; Dong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, B.Y.; Bai, J.; Yan, D.J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, D.Q.; Pei, Y.H.; et al. Diphenyl ethers from a marine-derived Aspergillus sydowii. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.L.; Wang, X.J.; Xiang, Z.D.; Wang, J.D.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.X.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, W.S. Diphenyl etheric metabolites from Streptomyces sp. Neau50. J. Antibiot. 2011, 64, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanahashi, T.; Takenaka, Y.; Nagakura, N.; Hamada, N. Dibenzofurans from the cultured lichen mycobionts of Lecanora cinereocarnea. Phytochemistry 2001, 58, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Y.; Liu, M.M.; Jenkins, I.D.; Liu, X.T.; Zhang, L.X.; Quinn, R.J.; Feng, Y.J. Genome-inspired chemical exploration of marine fungus Aspergillus Fumigatus MF071. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Lin, Y.C. Three xanthones from a marine-derived mangrove endophytic fungus. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2007, 43, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, S.A.; Lee, S.U.; Asami, Y.; Ahn, J.S.; Oh, H.; Baltrusaitis, J.; Gloer, J.B.; Wicklow, D.T. Aflaquinolones A–G: Secondary metabolites from marine and fungicolous isolates of Aspergillus spp. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulistyowaty, M.I.; Uyen, N.H.; Suganuma, K.; Chitama, B.-Y.A.; Yahata, K.; Kaneko, O.; Sugimoto, S.; Yamano, Y.; Kawakami, S.; Otsuka, H.; et al. Six new phenylpropanoid derivatives from chemically converted extract of Alpinia galanga (L.) and their antiparasitic activities. Molecules 2021, 26, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.Y.; Tan, M.H.; Liu, C.X.; Lv, M.M.; Deng, Z.S.; Cao, F.; Zou, K.; Proksch, P. Aspergoterpenins A–D: Four new antimicrobial bisabolane sesquiterpenoid derivatives from an endophytic fungus Aspergillus versicolor. Molecules 2018, 23, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prachayasittikul, S.; Suphapong, S.; Worachartcheewan, A.; Lawung, R.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. Bioactive metabolites from Spilanthes acmella Murr. Molecules 2009, 14, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.J.; Liu, C.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Li, C.; Pei, Y.H. A new tetracyclic triterpenoid from endophytic fungus Fusarium sporotrichioides. Chin. Herb. Med. 2024, 16, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.W.; Lin, X.P.; Tao, H.M.; Wang, J.F.; Li, J.Y.; Yang, B.; Zhou, X.F.; Liu, Y.H. Isochromophilones A–F, cytotoxic chloroazaphilones from the marine mangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthe sp. SCSIO 41011. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Position | 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, Type | δH, (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH, (J in Hz) | |

| 2 | 169.4, C | 171.8, C | ||

| 3 | 109.8, CH | 6.23, s | 110.6, CH | 6.34, s |

| 4 | 183.9, C | 184.6, C | ||

| 4a | 113.4, C | 113.0, C | ||

| 5 | 156.5, C | 159.2, C | ||

| 5a | 126.2, C | 126.1, C | ||

| 6 | 109.3, C | 203.1, C | ||

| 7 | 166.7, C | 167.4, C | ||

| 7a | 133.8, C | 136.6, C | ||

| 8 | 103.9, CH | 7.36, s | 109.8, CH | 7.42, s |

| 8a | 158.3, C | 158.1, C | ||

| 9 | 20.9, CH3 | 2.46, s | 20.5, CH3 | 2.48, s |

| 10 | 23.8, CH3 | 1.94, s | 31.7, CH3 | 2.61, s |

| 11 | 51.8, CH3 | 3.17, s | 53.5, CH3 | 3.90, s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qi, X.; Li, Z.; Lin, M.; Lu, H.; Peng, S.; Qin, H.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C.; Luo, X. Two New Chromone Derivatives from a Marine Algicolous Fungus Aspergillus versicolor GXIMD 02518 and Their Osteoclastogenesis Inhibitory Activity. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110429

Qi X, Li Z, Lin M, Lu H, Peng S, Qin H, Liu Y, Gao C, Luo X. Two New Chromone Derivatives from a Marine Algicolous Fungus Aspergillus versicolor GXIMD 02518 and Their Osteoclastogenesis Inhibitory Activity. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(11):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110429

Chicago/Turabian StyleQi, Xin, Zhen Li, Miaoping Lin, Humu Lu, Shuai Peng, Huangxue Qin, Yonghong Liu, Chenghai Gao, and Xiaowei Luo. 2025. "Two New Chromone Derivatives from a Marine Algicolous Fungus Aspergillus versicolor GXIMD 02518 and Their Osteoclastogenesis Inhibitory Activity" Marine Drugs 23, no. 11: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110429

APA StyleQi, X., Li, Z., Lin, M., Lu, H., Peng, S., Qin, H., Liu, Y., Gao, C., & Luo, X. (2025). Two New Chromone Derivatives from a Marine Algicolous Fungus Aspergillus versicolor GXIMD 02518 and Their Osteoclastogenesis Inhibitory Activity. Marine Drugs, 23(11), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110429