Relationship Between the Degree of Diabetic Retinopathy and Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

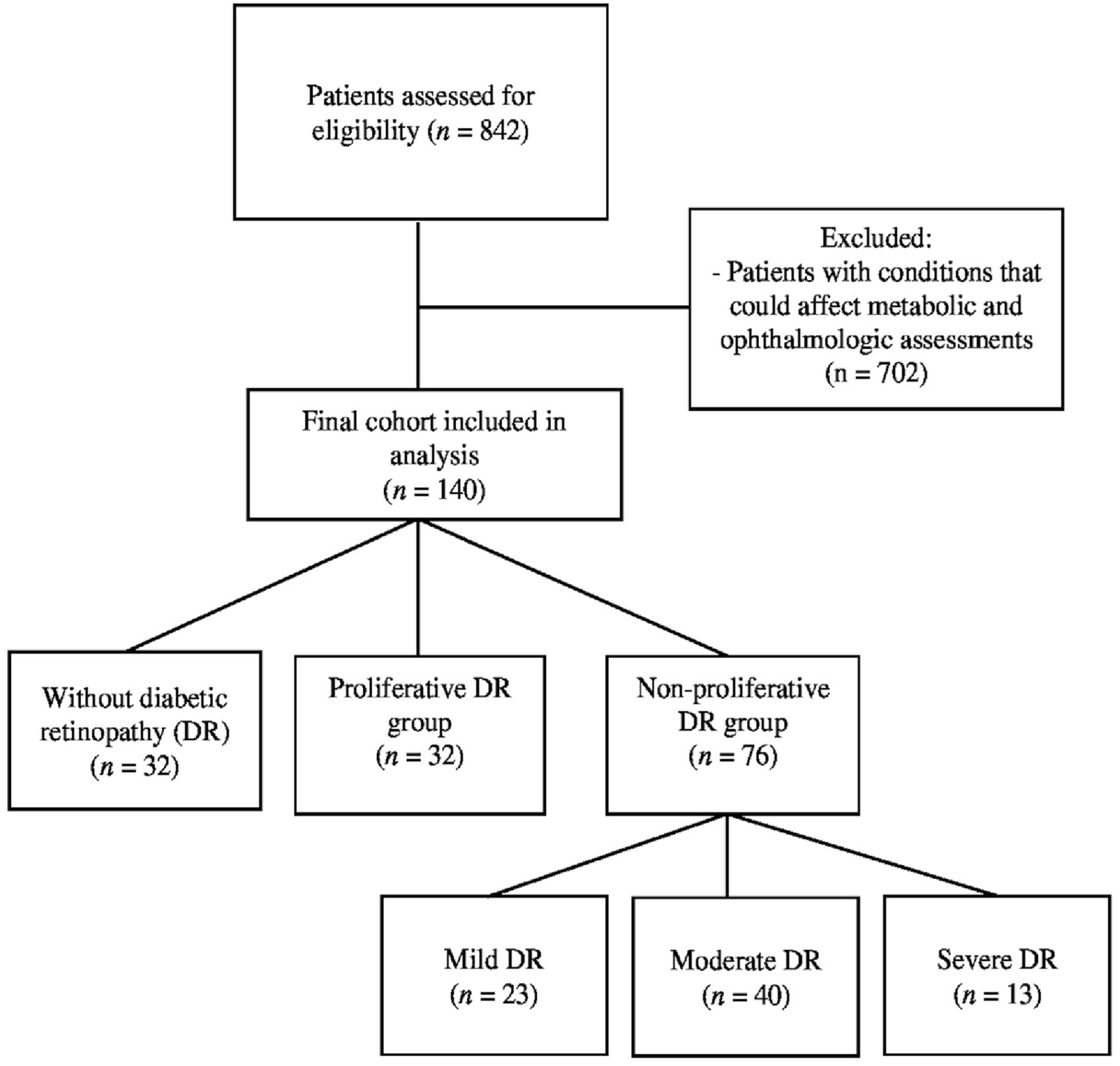

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Diabetic Retinopathy Assessment Method

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Blood Sampling and Biochemical Analysis

2.6. Measurement of Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) Levels

2.7. Outcomes

2.8. Statistical Analysis

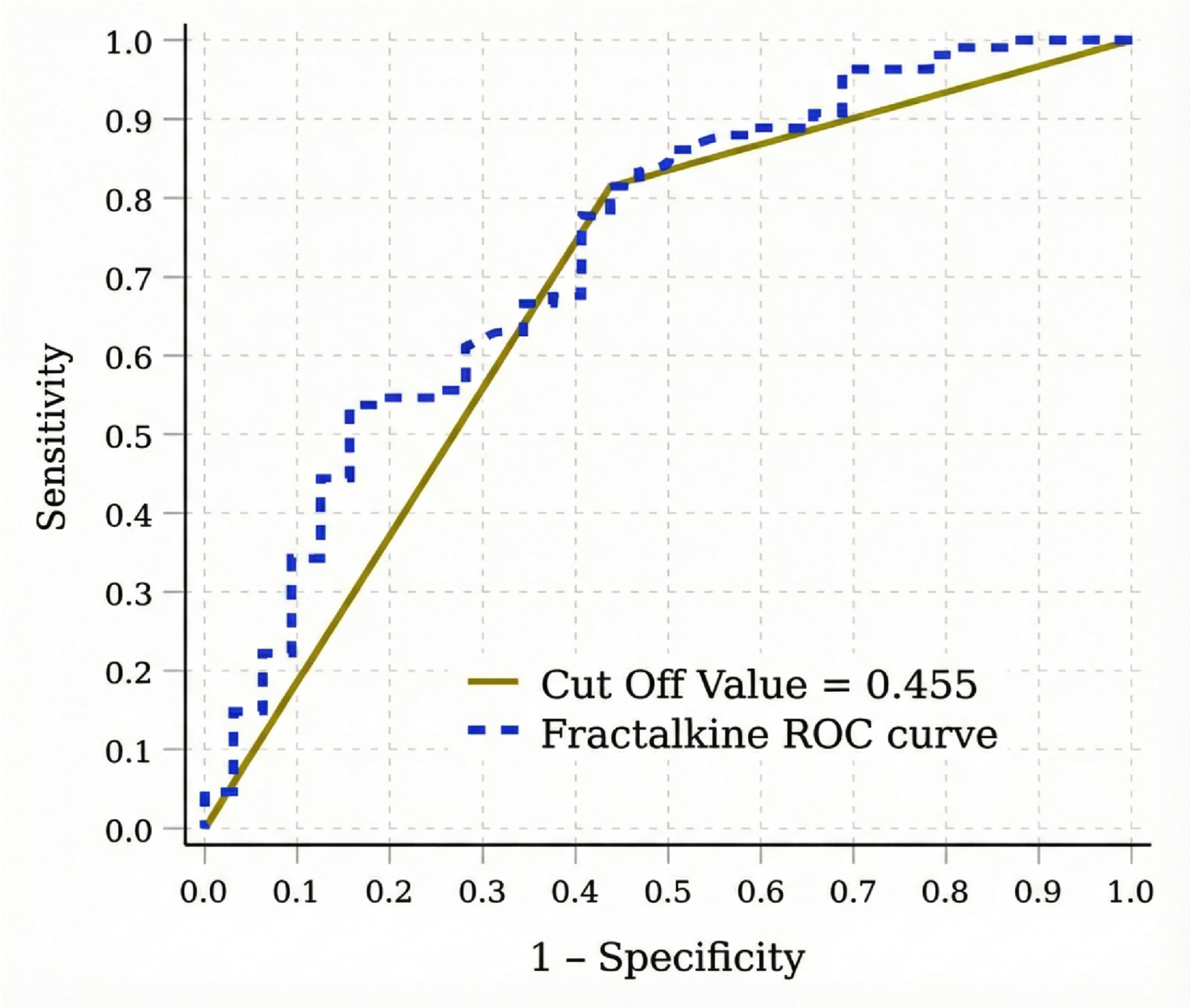

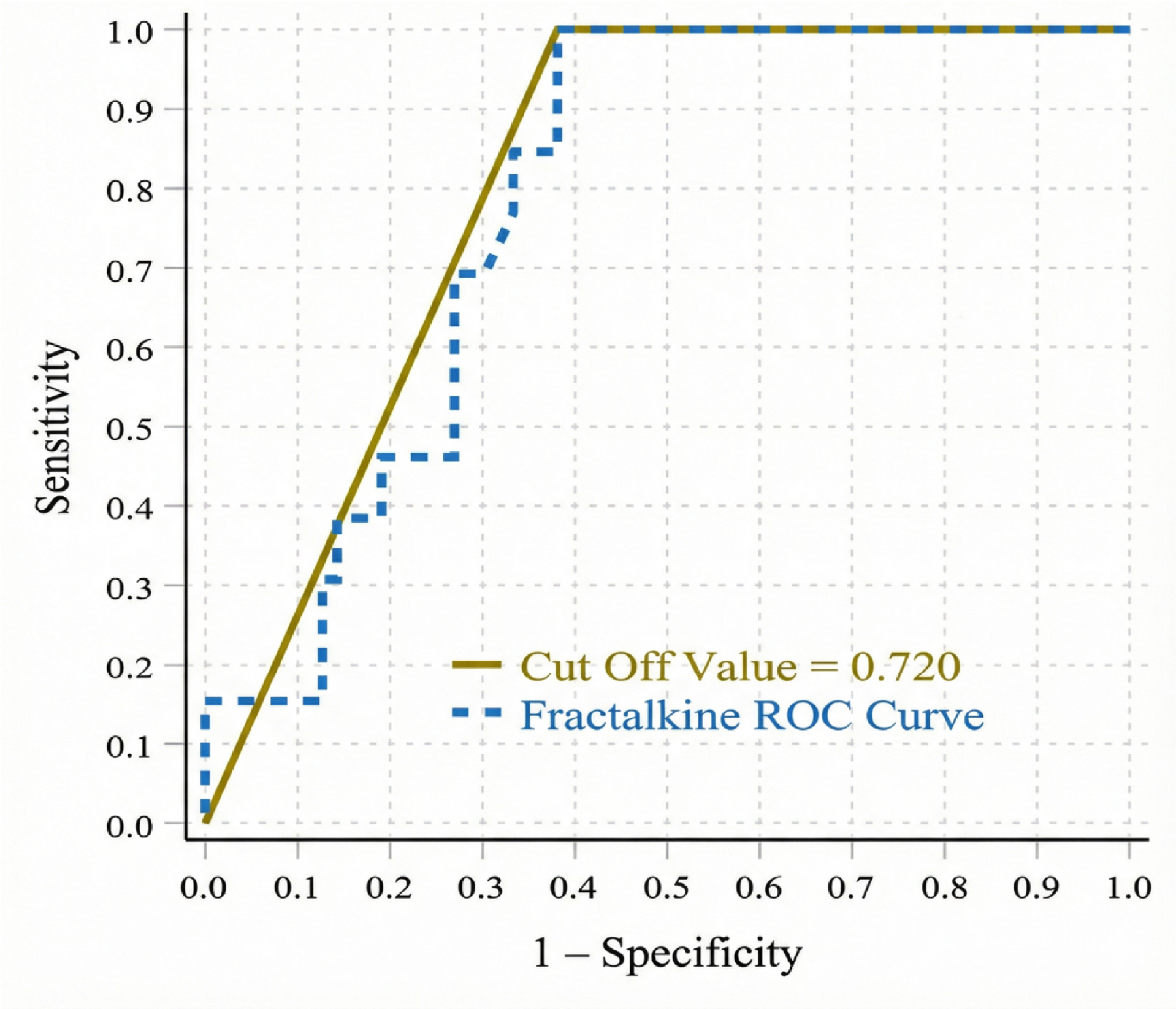

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DR | Diabetic retinopathy |

| PDR | Proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| NPDR | Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| CX3CL1 | Fractalkine |

| CX3CR1 | CX3C chemokine receptor 1 |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| ADA | American diabetes association |

| ICDR | International clinical diabetic retinopathy severity scale |

| ETDRS | Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c (Glycated Hemoglobin) |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| ADAM10 | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase Domain-Containing Protein 10 |

| ADAM17 | A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase Domain-Containing Protein 17 |

| UKPDS 33 | The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 33 |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| TMB | Tetramethylbenzidine |

References

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.C.; Yu, M.; Chee, M.L.; Rim, T.H.; Cheung, N.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Global Prevalence of Diabetic Retinopathy and Projection of Burden through 2045: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitt, A.W.; Curtis, T.M.; Chen, M.; Medina, R.J.; McKay, G.J.; Jenkins, A.; Gardiner, T.A.; Lyons, T.J.; Hammes, H.-P.; Simó, R.; et al. The progress in understanding and treatment of diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 51, 156–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonetti, D.A.; Barber, A.J.; Bronson, S.K.; Freeman, W.M.; Gardner, T.W.; Jefferson, L.S.; Kester, M.; Kimball, S.R.; Krady, J.K.; LaNoue, K.F.; et al. Diabetic retinopathy: Seeing beyond glucose-induced microvascular disease. Diabetes 2006, 55, 2401–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, H.P.; Lin, J.; Renner, O.; Shani, M.; Lundqvist, A.; Betsholtz, C.; Brownlee, M.; Deutsch, U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 2002, 51, 3107–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simó, R.; Stitt, A.W.; Gardner, T.W. Neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: Does it really matter? Diabetologia 2018, 61, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; Chew, E.; Duh, E.J.; Sobrin, L.; Sun, J.K.; VanderBeek, B.L.; Wykoff, C.C.; Gardner, T.W. Diabetic Retinopathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Kern, T.S. Inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Yang, C.H. The Role of Fractalkine in Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Yang, C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, J.F.; Bacon, K.B.; Hardiman, G.; Wang, W.; Soo, K.; Rossi, D.; Greaves, D.R.; Zlotnik, A.; Schall, T.J. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature 1997, 385, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.E.; Greaves, D.R. Fractalkine: A survivor’s guide: Chemokines as antiapoptotic mediators. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.J.; Yang, C.H.; Huang, J.S.; Chen, M.S.; Yang, C.M. Fractalkine, a CX3C chemokine, as a mediator of ocular angiogenesis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5290–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, S.M.; Mendiola, A.S.; Yang, Y.C.; Adkins, S.L.; Torres, V.; Cardona, A.E. Disruption of Fractalkine Signaling Leads to Microglial Activation and Neuronal Damage in the Diabetic Retina. ASN Neuro 2015, 7, 1759091415608204. [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola, A.S.; Garza, R.; Cardona, S.M.; Mythen, S.A.; Lira, S.A.; Akassoglou, K.; Cardona, A.E. Fractalkine Signaling Attenuates Perivascular Clustering of Microglia and Fibrinogen Leakage during Systemic Inflammation in Mouse Models of Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, D.; Church, K.A.; Pietramale, A.N.; Cardona, S.M.; Vanegas, D.; Rorex, C.; Leary, M.C.; Muzzio, I.A.; Nash, K.R.; Cardona, A.E. Fractalkine isoforms differentially regulate microglia-mediated inflammation and enhance visual function in the diabetic retina. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra, A.M.; Waddell, J.; Manivannan, A.; Xu, H.; Cotter, M.; Forrester, J.V. CD11b+ bone marrow-derived monocytes are the major leukocyte subset responsible for retinal capillary leukostasis in experimental diabetes in mouse and express high levels of CCR5 in the circulation. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchini, F.; Mancin, S.; Cangelosi, G.; Palomares, S.M.; Caggianelli, G.; Gravante, F.; Petrelli, F. The role of artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy screening in type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2025, 39, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musetti, D.; Cutolo, C.A.; Bonetto, M.; Giacomini, M.; Maggi, D.; Viviani, G.L.; Gandin, I.; Traverso, C.E.; Nicolò, M. Autonomous artificial intelligence versus teleophthalmology for diabetic retinopathy. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 35, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Introduction and Methodology: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, S1–S4. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE reporting checklist. EQUATOR Netw. 2025.

- Wilkinson, C.P.; Ferris, F.L.; Klein, R.E.; Lee, P.P.; Agardh, C.D.; Davis, M.; Dills, D.; Kampik, A.; Pararajasegaram, R.; Verdaguer, J.T. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs. Ophthalmology 1991, 98, 786–806. [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.A.; Jobling, A.I.; Dixon, M.A.; Bui, B.V.; Vessey, K.A.; Phipps, J.A.; Greferath, U.; Venables, G.; Wong, V.H.Y.; Wong, C.H.Y.; et al. Fractalkine-induced microglial vasoregulation occurs within the retina and is altered early in diabetic retinopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2112561118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Matthews, G.J.; Shah, R.Y.; McLaughlin, C.; Chen, J.; Wolman, M.; Master, S.R.; Chai, B.; Xie, D.; Rader, D.J.; et al. Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) and Cardiovascular Outcomes and Diabetes: Findings from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monickaraj, F.; Acosta, G.; Cabrera, A.P.; Das, A. Transcriptomic Profiling Reveals Chemokine CXCL1 as a Mediator for Neutrophil Recruitment Associated with Blood-Retinal Barrier Alteration in Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes 2023, 72, 781–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Bisht, K.; Tremblay, M.È. Fractalkine regulation of microglial physiology and consequences on the brain and behavior. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu El-Asrar, A.M.; Nawaz, M.I.; Ahmad, A.; De Zutter, A.; Siddiquei, M.M.; Blanter, M.; Allegaert, E.; Gikandi, P.W.; De Hertogh, G.; Van Damme, J.; et al. Evaluation of Proteoforms of the Transmembrane Chemokines CXCL16 and CX3CL1, Their Receptors, and Their Processing Metalloproteinases ADAM10 and ADAM17 in Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 601–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratton, I.M.; Adler, A.I.; Neil, H.A.; Matthews, D.R.; Manley, S.E.; Cull, C.A.; Hadden, D.; Turner, R.C.; Holman, R.R. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): Prospective observational study. BMJ 2000, 321, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, R.; Torres, M.; Peña, F.; Klein, R.; Azen, S.P.; Los Angeles Latino Eye Study Group. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in adult Latinos: The Los Angeles Latino eye study. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998, 352, 837–853, Erratum in Lancet 1999, 354, 602.. [CrossRef]

- Writing Team for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2002, 287, 2563–2569. [CrossRef]

- Varadhan, L.; Humphreys, T.; Hariman, C.; Walker, A.B.; Varughese, G.I. GLP-1 agonist treatment: Implications for diabetic retinopathy screening. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 94, e68–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Asrar, A.M.; Al-Rubeaan, K.A.; Al-Amro, S.A.; Moharram, O.A.; Kangave, D. Retinopathy as a predictor of other diabetic complications. Int. Ophthalmol. 2001, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Su, X.; Ye, Q.; Guo, X.; Xu, B.; Guan, T.; Chen, A. The predictive value of diabetic retinopathy on subsequent diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ren. Fail. 2021, 43, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.; Mustafa, N.; Fawwad, A.; Askari, S.; Haque, M.S.; Tahir, B.; Basit, A. Relationship between diabetic retinopathy and diabetic nephropathy; A longitudinal follow-up study from a tertiary care unit of Karachi, Pakistan. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 1659–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaviat, M.R.; Afkhami, M.; Shoja, M.R. Retinopathy and microalbuminuria in type II diabetic patients. BMC Ophthalmol. 2004, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, R.; Pillai, G.S.; Kumar, H.; Shajan, A.T.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Ravindran, G.C. Relationship between diabetic retinopathy and diabetic peripheral neuropathy—Neurodegenerative and microvascular changes. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 3370–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwahashi, Y.; Ishida, Y.; Mukaida, N.; Kondo, T. Pathophysiological Roles of the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 Axis in Renal Disease, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Without Retinopathy (n = 32) | With Retinopathy (n = 108) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 53 (48–59) | 59 (52–66) | 0.071 |

| DM duration, year | 3.5 (1–30) | 10 (1–35) | <0.001 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (40.6) | 58 (53.7) | 0.194 |

| Male | 19 (59.4) | 50 (46.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.2 ± 4.9 | 29 ± 4.4 | 0.180 |

| HT, n (%) | |||

| Absent | 26 (81.2) | 68 (63) | 0.053 |

| Present | 6 (18.8) | 40 (37) | |

| Smoking Status, n (%) | |||

| No | 29 (90.6) | 91 (84.3) | 0.366 |

| Yes | 3 (9.4) | 17 (15.7) | |

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Oral Antidiabetic | 23 (71.9) | 46 (42.6) | 0.004 |

| Insulin | 2 (6.3) | 7 (6.5) | 0.963 |

| Insulin + OAD | 7 (21.9) | 51 (42.2) | 0.011 |

| Antihypertensive | 6 (18.8) | 36 (33.3) | 0.114 |

| Parameters | Without Retinopathy (n = 32) | With Retinopathy (n = 108) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractalkine, ng/mL | 0.4 (0.4–0.95) | 0.7 (0.42–0.85) | <0.001 |

| CRP, mg/L | 2.8 (1.5–5.5) | 3.7 (2.1–7.3) | 0.773 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 152.5 (119–223) | 212.5 (163–276) | 0.022 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.6 (6.7–9.8) | 9.1 (8.1–9.8) | 0.004 |

| HOMA-IR | 4.7 (2.6–7.1) | 4.4 (2.3–6.7) | 0.749 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 29.9 (23–37) | 34 (28–41) | 0.008 |

| UACR, mg/g | 13.9 (7.5–58.2) | 35.3 (16.6–157) | 0.003 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1) | <0.001 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 117 (89–152) | 117.5 (90–152) | 0.656 |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 44.5 (36–50) | 42 (38–53) | 0.356 |

| TG, mg/dL | 191.5 (120–242) | 175.5 (126–232) | 0.580 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 184 (166–221) | 194.5 (153–231) | 0.962 |

| WBC, 103/mm3 | 7.3 (6.9–9.3) | 8.2 (7.3–10.2) | 0.013 |

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | %95 CI | p | OR | %95 CI | p | |

| Duration of diabetes | 1.18 | 1.09–1.28 | <0.001 | 1.17 | 1.06–1.28 | 0.001 |

| Fractalkine | 25.3 | 4.1–154.4 | <0.001 | 10.2 | 1.2–89.6 | 0.036 |

| Glucose | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.032 | |||

| HbA1c | 1.42 | 1.11–1.81 | 0.005 | 1.42 | 1.08–1.87 | 0.012 |

| UACR | 1.001 | 1–1.001 | 0.201 | |||

| Creatinine | 22.75 | 3.41–152.0 | 0.001 | 20.78 | 1.97–219.1 | 0.012 |

| WBC | 1.32 | 1.06–1.65 | 0.014 | |||

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | %95 CI | p | OR | %95 CI | p | |

| Duration of diabetes | 1.25 | 1.03–1.53 | 0.023 | 1.22 | 0.97–1.52 | 0.077 |

| Fractalkine | 7.53 | 0.52–108 | 0.138 | |||

| Creatinine | 2.40 | 1.59–3.62 | 0.032 | 2.21 | 0.59–8.20 | 0.074 |

| UACR | 1.01 | 0.99–1.19 | 0.325 | |||

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | %95 CI | p | OR | %95 CI | p | |

| Duration of diabetes | 1.14 | 1.04–1.25 | 0.003 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 0.006 |

| Fractalkine | 34.0 | 3.38–342 | 0.003 | 52.6 | 3.35–825 | 0.005 |

| Creatinine | 1.25 | 1.00–11.0 | 0.023 | 0.81 | 0.08–7.9 | 0.075 |

| UACR | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.386 | |||

| Parameters | Proliferative DR (n = 32) | Non-Proliferative DR (n = 76) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fractalkine, ng/mL | 0.5 (0.38–1.03) | 0.7 (0.44–0.83) | 0.274 |

| CRP, mg/L | 4.5 (2–7) | 3.1 (1–6) | 0.668 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 209 (165–300) | 215.5 (158–265) | 0.696 |

| HbA1c, % | 9.6 (8–9.8) | 9 (8.4–9.7) | 0.279 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.7 (2.3–6.3) | 4.8 (2.3–7.2) | 0.623 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 33 (31–54) | 35 (26–41) | 0.497 |

| UACR, mg/g | 65.6 (14–150) | 33.3 (16–244) | 0.218 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.8–1) | 0.9 (0.7–1) | 0.893 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 127 (90–150) | 118 (90–154) | 0.326 |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 44 (38–53) | 43 (38–54) | 0.731 |

| TG, mg/dL | 187.8 ± 94.5 | 181.8 ± 87 | 0.751 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 204 (147–231) | 190 (153–231) | 0.214 |

| WBC, 103/mm3 | 8.2 (7.4–9.7) | 8.2 (7.2–10.5) | 0.797 |

| Parameters | Mild Non-Proliferative DR (n = 23) | Moderate Non-Proliferative DR (n = 40) | Severe Non-Proliferative DR (n = 13) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractalkine, ng/mL | 0.68 (0.41–0.79) | 0.63 (0.46–0.91) | 0.83 (0.45–0.93) * | 0.004 |

| CRP, mg/L | 2.2 (1–5) | 4.4 (2–13) | 2.5 (2–8) | 0.092 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 218 (165–269) | 197.5 (136–267) | 244 (162–246) | 0.992 |

| HbA1c, % | 9.2 (7.9–10.1) | 8.8 (8–9.4) | 9.2 (8.7–9.7) | 0.788 |

| HOMA-IR | 5 (3.3–6.7) | 4.7 (2–7.6) | 4.1 (2.4–7) | 0.881 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 33 (25–36) | 33.5 (24–41) | 36.7 (28–41) | 0.777 |

| UACR, mg/g | 20.8 (8.7–119) ¥ | 49.3 (25–325) | 45 (30–338) | 0.015 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.589 |

| LDL-c, mg/dL | 115.5 ± 36.5 | 118.7 ± 43.5 | 125.9 ± 33.7 | 0.754 |

| HDL-c, mg/dL | 41 (36–55) | 40 (38–53) | 43 (40–54) | 0.328 |

| TG, mg/dL | 164.8 ± 67.7 | 193.5 ± 100.7 | 176 ± 69.7 | 0.442 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 183 (169–233) | 190 (147–212) | 217 (181–251) | 0.251 |

| WBC, 103/mm3 | 8.5 ± 2.5 | 8.7 ± 2.1 | 8.7 ± 1.9 | 0.772 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yilmaz, O.; Erdogan, M.; Algemi, M.; Kocak, I.; Yoldemir, S.A.; Akarsu, M. Relationship Between the Degree of Diabetic Retinopathy and Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2026, 62, 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020312

Yilmaz O, Erdogan M, Algemi M, Kocak I, Yoldemir SA, Akarsu M. Relationship Between the Degree of Diabetic Retinopathy and Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):312. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020312

Chicago/Turabian StyleYilmaz, Ozgur, Mehmet Erdogan, Murvet Algemi, Ibrahim Kocak, Sengul Aydin Yoldemir, and Murat Akarsu. 2026. "Relationship Between the Degree of Diabetic Retinopathy and Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study" Medicina 62, no. 2: 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020312

APA StyleYilmaz, O., Erdogan, M., Algemi, M., Kocak, I., Yoldemir, S. A., & Akarsu, M. (2026). Relationship Between the Degree of Diabetic Retinopathy and Serum Fractalkine (CX3CL1) in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Single-Center Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina, 62(2), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020312