Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Suicide Attempts by Drug Overdose: A Comparative Study with a Comparison Group

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Selection Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Inclusion Criteria

- To be aged 18 and over;

- To have died by suicide via overdosing;

- To be kept under surveillance by being hospitalized in the Internal Medicine Clinic;

- To have the complete document of the hemogram and biochemical data belonging to the period of application and discharge.

2.2.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Having an overdose without thinking of committing suicide;

- Having an overdose by accident or by mistake;

- The attempted suicide through methods except for medication;

- Having alcohol or psychoactive substance abuse;

- The existence of acute or chronic inflammatory disease;

- The existence of infectious, endocrinologic, or autoimmune disease;

- The use of medicine that affects the function of bone marrow;

- Lack of data about the laboratory data belonging to the period of application or discharge.

2.2.4. Data Collection

2.2.5. Medication Classification

2.3. The Calculation of the Laboratory Analysis and Inflammatory Indexes

- CRP/Albumin Ratio: (CAR)/Albumin;

- The Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR): Neutrophil Count/Lymphocyte Count;

- Monocyte Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR): Monocyte Count/Lymphocyte Count;

- Platelet/Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR): Platelet Count/Lymphocyte Count;

- Systemic İmmune-Inflammation Index (SIII): (Neutrophil Count × Platelet Count)/Lymphocyte Count.

2.4. Ethical Approval

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delaney, S.; Fallon, B.; Alaedini, A.; Yolken, R.; Indart, A.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y.; Javitt, D. Inflammatory biomarkers in psychosis and clinical high risk populations. Schizophr. Res. 2019, 206, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Soczynska, J.K.; Kennedy, S.H. Inflammatory biomarkers in depression: An opportunity for novel therapeutic interventions. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2011, 13, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Caso, J.R.; García-Portilla, M.P.; De la Fuente-Tomás, L.; González-Blanco, L.; Sáiz-Martinez, P.; Leza, J.C.; Bobes, J. Regulation of inflammatory pathways in schizophrenia: A comparative study with bipolar disorder and healthy controls. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 47, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fadhel, S.Z.; Al-Hakeim, H.K.; Al-Dujaili, A.H.; Maes, M. IL-10 is associated with increased mu-opioid receptor levels in major depressive disorder. Eur. Psychiatry 2019, 57, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, M. Suicide prevention: A multisectorial public health concern. Prev. Med. 2021, 152, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.; Miller, B.J. Meta-Analysis of Cytokines and Chemokines in Suicidality: Distinguishing Suicidal Versus Nonsuicidal Patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 78, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguglia, A.; Natale, A.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Gnecco, G.B.; Lechiara, A.; Marino, M.; Meinero, M.; Pastorino, F.; Costanza, A.; Spedicato, G.A.; et al. C-Reactive Protein as a Potential Peripheral Biomarker for High-Lethality Suicide Attempts. Life 2022, 12, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chang, Q.; Meng, X.; Gao, N.; Wang, W. Prognostic value of Systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3295–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.H.; Huang, D.H.; Chen, Z.Y. Prognostic role of systemic immune-inflammation index in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 75381–75388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, V.; Wu, C.; Huang, C.; Baune, B.T.; Tseng, C.; McLachlan, C.S. Elevated neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts mortality in medical inpatients with multiple chronic conditions. Medicine 2016, 95, e0916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, D.R.; Rapaport, M.H.; Miller, B.J. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: Comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 1696–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, R.; O’Connor, J.C.; Freund, G.G.; Johnson, R.W.; Kelley, K.W. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshfeghinia, R.; Kavari, K.; Mostafavi, S.; Sanaei, E.; Farjadian, S.; Javanbakht, A. Haematological markers of inflammation in major depressive disorder (MDD) patients with suicidal behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 385, 119371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastava, S.; Sharma, B.; Avasthi, R.K.; Kotru, M. Comparison Between Inflammatory Biomarkers (High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio) and Psychological Morbidity in Suicide Attempt Survivors Brought to Medicine Emergency. Cureus 2021, 13, e17459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batty, G.D.; Bell, S.; Stamatakis, E.; Kivimäki, M. Association of Systemic Inflammation With Risk of Completed Suicide in the General Population. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundin, L.; Bryleva, E.Y.; Thirtamara Rajamani, K. Role of Inflammation in Suicide: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, B.R.; Kaysen, G. Serum albumin: Relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Semin. Dial. 2004, 17, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.C.; Crozier, J.E.; Canna, K.; Angerson, W.J.; McArdle, C.S. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) in patients undergoing resection for colon and rectal cancer. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2007, 22, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, A.; Onoda, H.; Imai, N.; Iwaku, A.; Oishi, M.; Tanaka, K.; Fushiya, N.; Koike, K.; Nishino, H.; Matsushima, M. The C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, a novel inflammation-based prognostic score, predicts outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhang, M. C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio is associated with increased depression: An exploratory cross-sectional analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 382, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, Á.; Rodríguez-Revuelta, J.; Olié, E.; Abad, I.; Fernández-Peláez, A.; Cazals, A.; Guillaume, S.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Jiménez-Treviño, L.; Gutiérrez, L.; et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: A potential new peripheral biomarker of suicidal behavior. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayhan, F.; Gündüz, Ş.; Ersoy, S.A.; Kandeğer, A.; Annagür, B.B. Relationships of neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios with the severity of major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 247, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivković, M.; Pantović-Stefanović, M.; Dunjić-Kostić, B.; Jurišić, V.; Lačković, M.; Totić-Poznanović, S.; Jovanović, A.A.; Damjanović, A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicting suicide risk in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: Moderatory effect of family history. Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 66, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varatharaj, A.; Galea, I. The blood-brain barrier in systemic inflammation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, V.H.; Teeling, J. Microglia and macrophages of the central nervous system: The contribution of microglia priming and systemic inflammation to chronic neurodegeneration. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhabhar, F.S. Effects of stress on immune function: The good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol. Res. 2014, 58, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, M.G.; Tringali, A.G.M.; Rossetti, A.; Botti, R.E.; Clerici, M. Cross-sectional study of neutrophil-lymphocyte, platelet-lymphocyte and monocyte-lymphocyte ratios in mood disorders. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, S.; Demırkol, S.; Kucuk, U. The platelet lymphocyte ratio may be useful inflammatory indicator in clinical practice. Hemodial. Int. 2013, 17, 668–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Tong, Y.; Tan, Y. Neutrophil/lymphocyte, platelet/lymphocyte, monocyte/lymphocyte ratios and systemic immune-inflammation index in patients with depression. Bratisl. Med. J. 2023, 124, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Torrigiani, S.; Carbone, M.G.; Mucci, F.; Flamini, W.; Ivaldi, T.; Dell’Osso, L. Neutrophil/Lymphocyte, Platelet/Lymphocyte, and Monocyte/Lymphocyte Ratios in Mood Disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 5758–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, G.N.; Pandey, S.C.; Dwivedi, Y.; Sharma, R.P.; Janicak, P.G.; Davis, J.M. Platelet serotonin-2A receptors: A potential biological marker for suicidal behavior. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovacic, Z.; Henigsberg, N.; Pivac, N.; Nedic, G.; Borovecki, A. Platelet serotonin concentration and suicidal behavior in combat related posttraumatic stress disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinko, D.; Pivac, N.; Martinac, M.; Jakovljević, M.; Mihaljević-Peles, A.; Muck-Seler, D. Platelet serotonin and serum cholesterol concentrations in suicidal and non-suicidal male patients with a first episode of psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 150, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Patient Group (n = 343) | Comparison Group (n = 421) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 31.12 ± 11.30 a | 32.64 ± 13.29 a | 0.088 b |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 104 (30.3%)/239 (69.7%) | 130 (30.9%)/291 (69.1%) | 0.868 c |

| Marital Status (Married) | 176 (51.3%) | 214 (50.8%) | 0.895 c |

| Experience of Suicide Attempts (%) | 23 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 c |

| Psychiatric diagnosis (%) | 111 (32.4%) | 0 (0%) | <0.001 c |

| Patients (n = 343) | |

|---|---|

| Psychiatric patient story (Yes/No) | |

| Yes | 111 (32.4%) |

| No | 232 (67.6%) |

| The group of Psychiatric illness diagnosis | |

| Mood disorders | 52 (15.2%) |

| Anxiety disorders | 22 (6.4%) |

| Psychotic disorders | 9 (2.6%) |

| Addiction disorders | 8 (2.3%) |

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | 6 (1.7%) |

| Bipolar and related disorders | 4 (1.2%) |

| Obsessive–Compulsive and related disorders | 4 (1.2%) |

| Others/symptom-based diagnoses | 4 (1.2%) |

| Impulse control disorder | 2 (0.6%) |

| Type of Medication | Patient Group (n = 343) |

|---|---|

| Psychiatric medication | 121 (35.3%) |

| Analgesics | 112 (32.7%) |

| Antibiotics | 41 (12.0%) |

| Toxic/non-pharmaceutical substances | 16 (4.7%) |

| Endocrine/metabolic medication | 13 (3.8%) |

| Cardiovascular medication | 12 (3.5%) |

| Antidiabetic medication | 8 (2.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal system medication | 6 (1.7%) |

| Respiratory & allergy medication | 5 (1.5%) |

| Others | 9 (2.6%) |

| Parameter | Patient Group (Admission) (n = 343) | Comparison Group (n = 421) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.60 [0.60–3.33] a | 0.24 [0.12–0.60] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.43 [4.24–4.64] a | 4.65 [4.50–4.86] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Leukocyte (103/µL) | 9.39 [7.68–11.07] a | 6.94 [6.06–8.10] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Neutrophil (103/µL) | 6.12 [4.78–7.58] a | 3.98 [3.30–4.75] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Lymphocyte (103/µL) | 2.33 [1.74–2.93] a | 2.34 [2.00–2.73] a | 0.677 b |

| Monocytes (103/µL) | 0.52 [0.41–0.64] a | 0.42 [0.35–0.51] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Platelet (103/µL) | 263 [224–310] a | 266 [233–298] a | 0.890 b |

| CAR | 0.37 [0.14–0.80] a | 0.04 [0.02–0.12] a | <0.001 b,* |

| NLR | 2.52 [1.84–3.59] a | 1.72 [1.34–2.05] a | <0.001 b,* |

| SIII | 685.24 [470–974] a | 447.88 [338–575] a | <0.001 b,* |

| PLR | 113.56 [87.07–145.74] a | 113.02 [95.66–133.45] a | 0.660 b |

| MLR | 0.21 [0.17–0.27] a | 0.17 [0.15–0.21] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Parameter | Application | Discharge | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.60 [0.60–3.33] a | 1.00 [0.60–2.17] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.43 [4.24–4.64] a | 4.10 [3.90–4.37] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Leukocyte (103/µL) | 9.39 [7.68–11.07] a | 7.96 [6.57–9.41] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Neutrophil (103/µL) | 6.12 [4.78–7.58] a | 4.54 [3.74–5.85] a | <0.001 b,* |

| Lymphocyte (103/µL) | 2.33 [1.74–2.93] a | 2.38 [1.93–3.02] a | 0.061 b |

| Monocytes (103/µL) | 0.52 [0.41–0.64] a | 0.51 [0.41–0.61] a | 0.350 b |

| Platelet (103/µL) | 263 [224–310] a | 241 [200–282] a | <0.001 b,* |

| CAR | 0.37 [0.14–0.80] a | 0.24 [0.13–0.53] a | <0.001 b,* |

| NLR | 2.52 [1.84–3.59] a | 1.92 [1.38–2.54] a | <0.001 b,* |

| SIII | 685.24 [470–974] a | 463.04 [326–647] a | <0.001 b,* |

| PLR | 113.56 [87.07–145.74] a | 101.87 [79.13–126.10] a | <0.001 b,* |

| MLR | 0.21 [0.17–0.27] a | 0.20 [0.16–0.26] a | 0.002 b,* |

| Parameter | Experience of Suicide Attempt (+) (n = 23) | Experience of Suicide Attempt (−) (n = 320) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.55 [0.37–3.20] a | 1.60 [0.60–3.35] b | 0.364 b |

| CAR | 0.36 [0.08–0.72] b | 0.38 [0.14–0.81] b | 0.370 b |

| NLR | 2.41 [1.83–3.00] b | 2.52 [1.83–3.59] b | 0.469 b |

| SIII | 650.79 [435.38–928.20] b | 686.70 [471.19–997.83] b | 0.812 b |

| PLR | 122.37 [92.34–163.02] b | 113.15 [86.84–144.52] b | 0.361 b |

| MLR | 0.19 [0.16–0.27] b | 0.21 [0.17–0.27] b | 0.590 b |

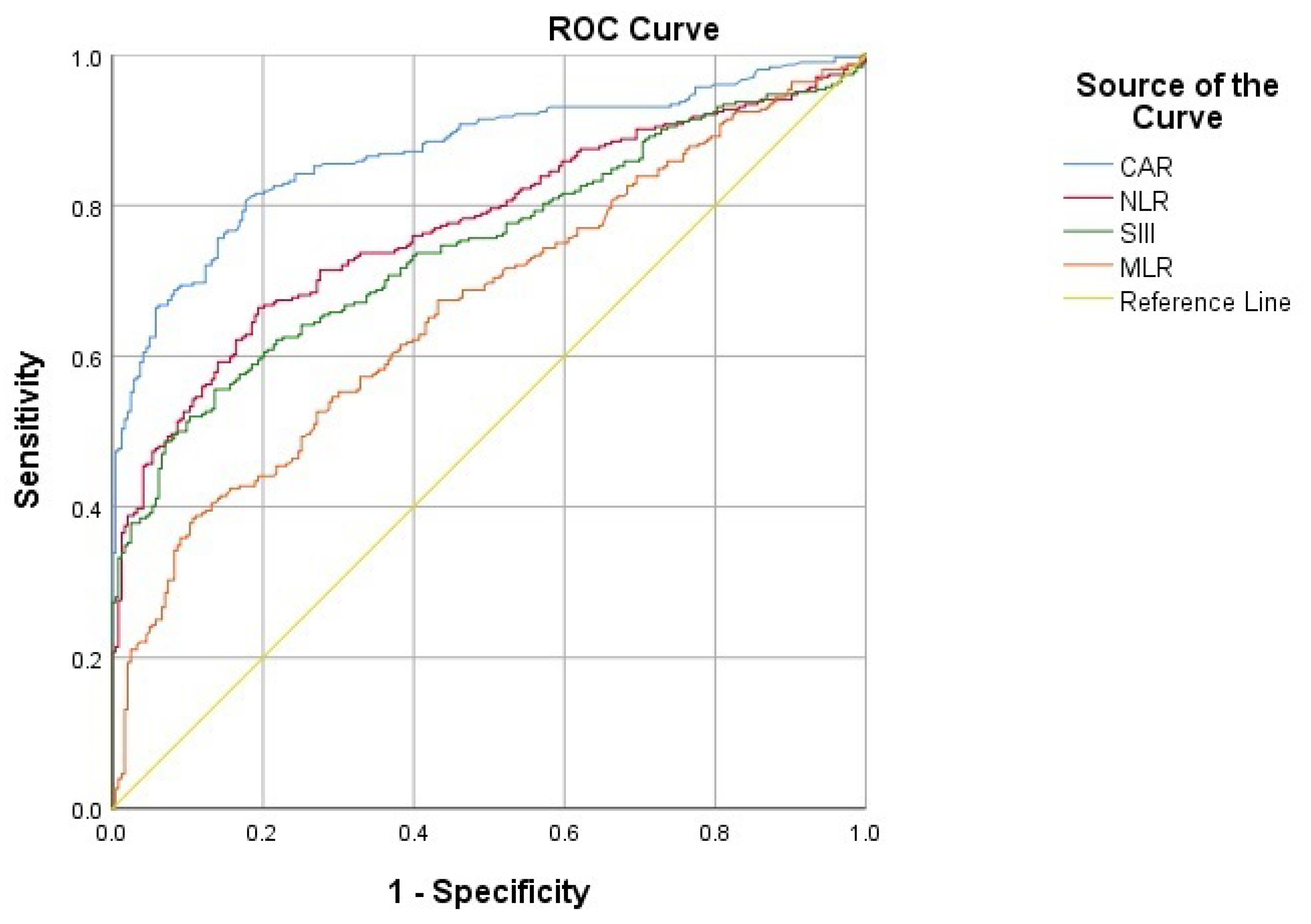

| Parameter | AUC (95% CI) | Cut-Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAR | 0.871 (0.841–0.901) | ≥0.13 | 80.6 | 82.3 | <0.001 * |

| NLR | 0.773 (0.734–0.812) | ≥2.14 | 66.4 | 80.7 | <0.001 * |

| SIII | 0.746 (0.706–0.787) | ≥647.16 | 55.6 | 86.4 | <0.001 * |

| MLR | 0.665 (0.620–0.710) | ≥0.23 | 38.5 | 89.3 | <0.001 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baş, S.; Danapınar, B.; Çetintulum Aydın, B.; Yeniçeri, M.; Şenoymak, M.C.; Arslan, K. Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Suicide Attempts by Drug Overdose: A Comparative Study with a Comparison Group. Medicina 2026, 62, 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020285

Baş S, Danapınar B, Çetintulum Aydın B, Yeniçeri M, Şenoymak MC, Arslan K. Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Suicide Attempts by Drug Overdose: A Comparative Study with a Comparison Group. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020285

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaş, Süleyman, Betül Danapınar, Büşra Çetintulum Aydın, Murat Yeniçeri, Mustafa Can Şenoymak, and Kadem Arslan. 2026. "Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Suicide Attempts by Drug Overdose: A Comparative Study with a Comparison Group" Medicina 62, no. 2: 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020285

APA StyleBaş, S., Danapınar, B., Çetintulum Aydın, B., Yeniçeri, M., Şenoymak, M. C., & Arslan, K. (2026). Inflammatory Parameters in Patients with Suicide Attempts by Drug Overdose: A Comparative Study with a Comparison Group. Medicina, 62(2), 285. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020285