Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Design and Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics and Associations

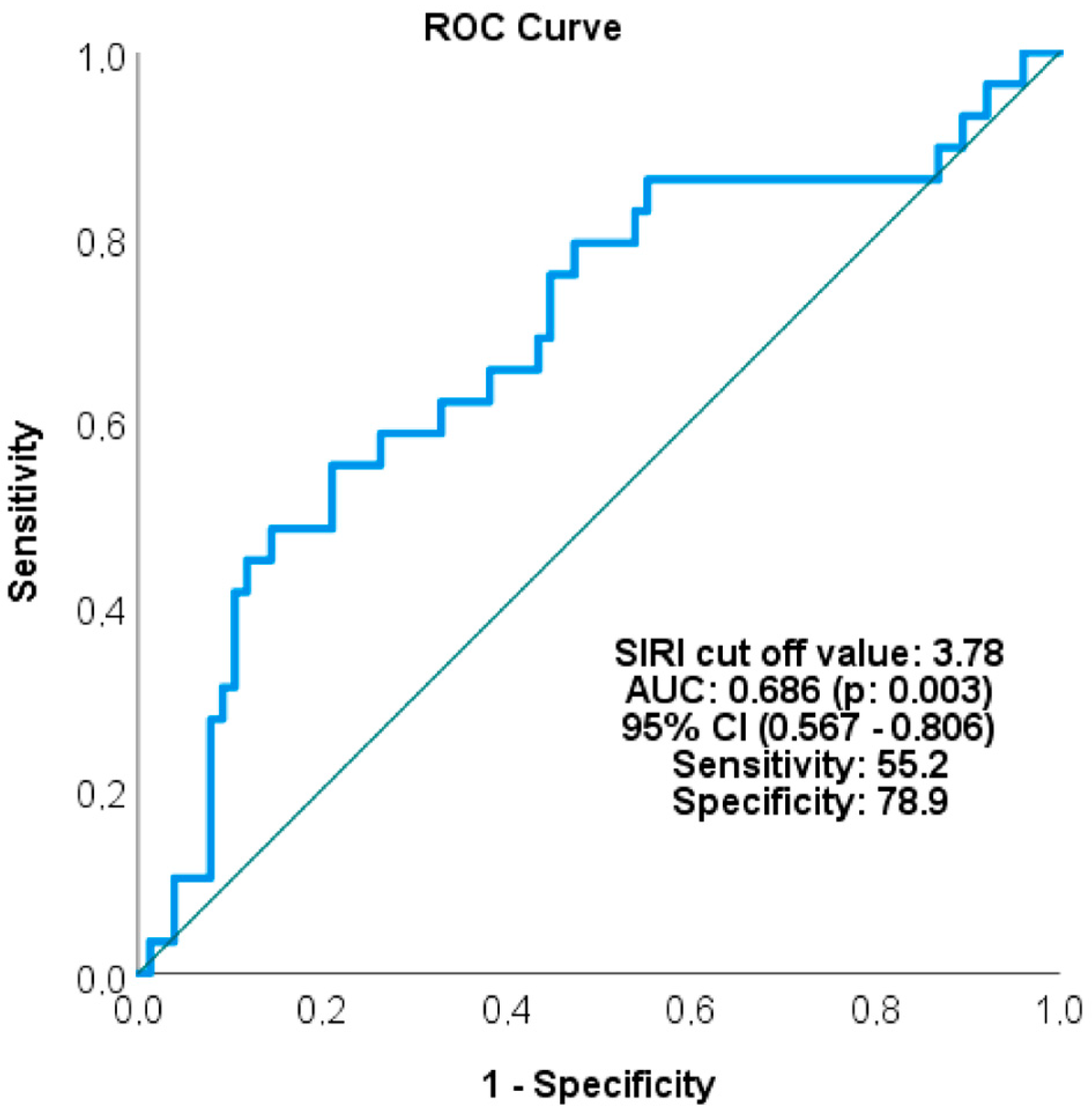

3.2. Survival Analyses

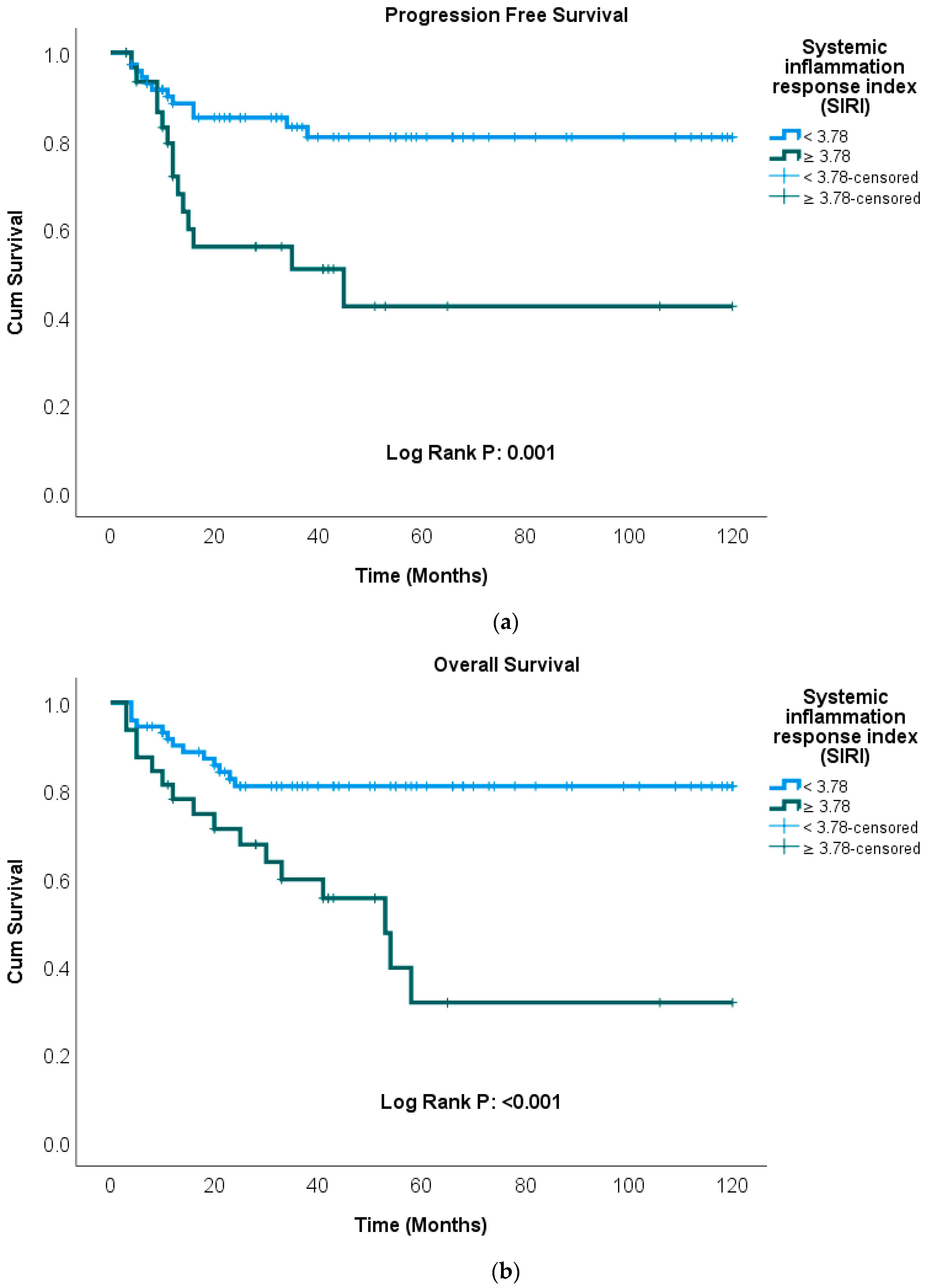

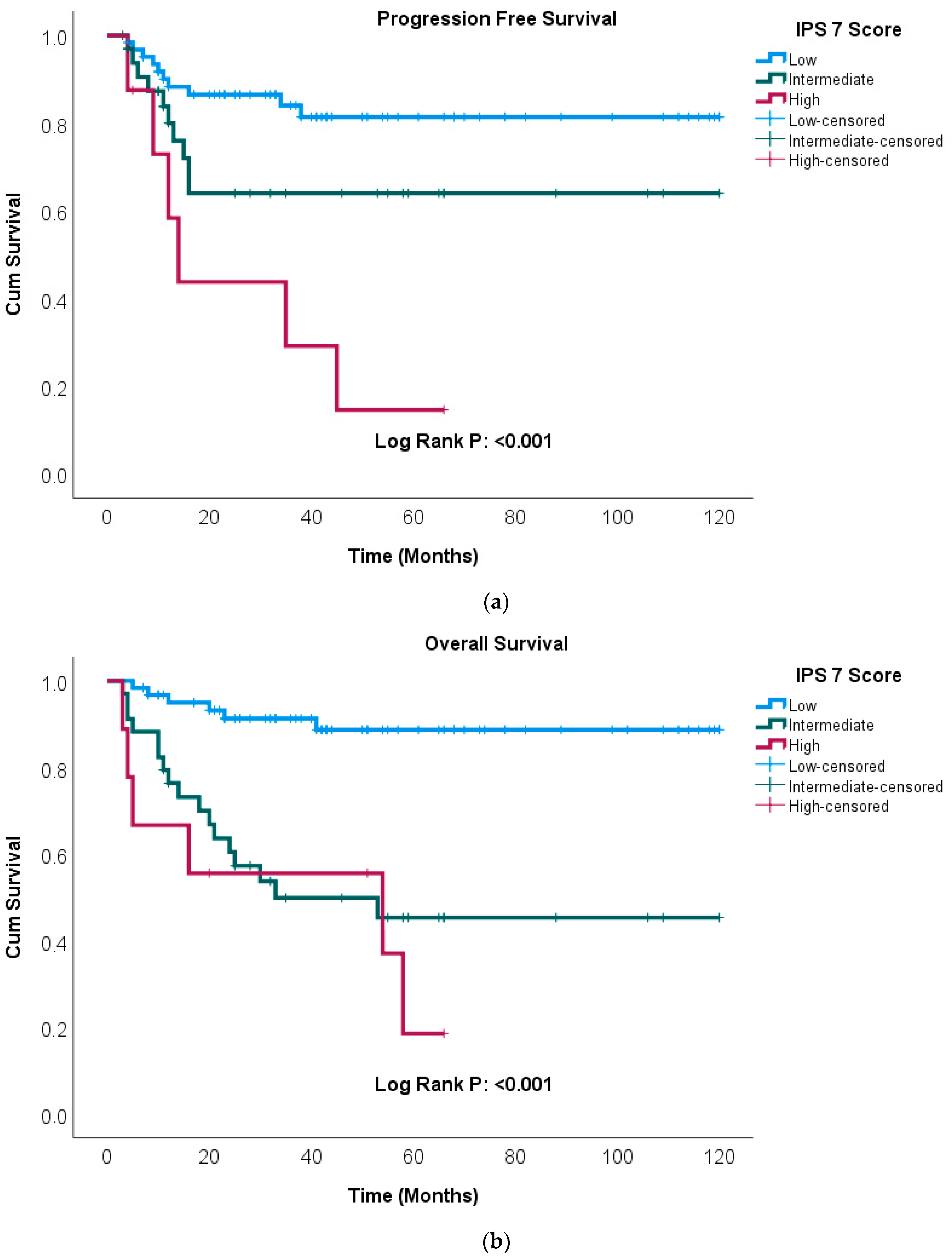

3.3. Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis

4. Discussion

Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eichenauer, D.A.; Aleman, B.M.P.; André, M.; Federico, M.; Hutchings, M.; Illidge, T.; Engert, A.; Ladetto, M. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Hodgkin lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, S.; Fanale, M.; DeVos, S.; Engert, A.; Illidge, T.; Borchmann, P.; Younes, A.; Morschhauser, F.; McMillan, A.; Horning, S.J. Defining a Hodgkin lymphoma population for novel therapeutics after relapse from autologous hematopoietic cell transplant. Leuk. Lymphoma 2013, 54, 2531–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansell, S.M.; Radford, J.; Connors, J.M.; Długosz-Danecka, M.; Kim, W.S.; Gallamini, A.; Ramchandren, R.; Friedberg, J.W.; Advani, R.; Hutchings, M.; et al. ECHELON-1 Study Group. Overall Survival with Brentuximab Vedotin in Stage III or IV Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.B.; Savas, H.; Evens, A.M.; Advani, R.H.; Palmer, B.; Pro, B.; Karmali, R.; Mou, E.; Bearden, J.; Dillehay, G.; et al. Pembrolizumab followed by AVD in untreated early unfavorable and advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2021, 137, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bröckelmann, P.J.; Bühnen, I.; Meissner, J.; Trautmann-Grill, K.; Herhaus, P.; Halbsguth, T.V.; Schaub, V.; Kerkhoff, A.; Mathas, S.; Bormann, M.; et al. Nivolumab and Doxorubicin, Vinblastine, and Dacarbazine in Early-Stage Unfavorable Hodgkin Lymphoma: Final Analysis of the Randomized German Hodgkin Study Group Phase II NIVAHL Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1193–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasenclever, D.; Diehl, V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, C.S.; Li, H.; Hong, F.; Gordon, L.I.; Fisher, R.I.; Bartlett, N.L.; Crump, M.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Wagner, H., Jr.; Stiff, P.J.; et al. Evaluation of the International Prognostic Score (IPS-7) and a Simpler Prognostic Score (IPS-3) for advanced Hodgkin lymphoma in the modern era. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 171, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Kang, S.Y.; He, X.H.; Liu, P.; Yang, S.; Zhou, S.Y.; Zhang, C.G.; Gui, L.; Yang, J.L.; et al. Decreased Prognostic Value of International Prognostic Score in Chinese Advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients Treated in the Contemporary Era. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 2780–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biccler, J.L.; El-Galaly, T.C.; Bøgsted, M.; Jørgensen, J.; de Nully Brown, P.; Poulsen, C.B.; Starklint, J.; Juul, M.B.; Christensen, J.H.; Josefsson, P.; et al. Clinical prognostic scores are poor predictors of overall survival in various types of malignant lymphomas. Leuk. Lymphoma 2019, 60, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triumbari, E.K.A.; Morland, D.; Cuccaro, A.; Maiolo, E.; Hohaus, S.; Annunziata, S. Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Joint Clinical and PET Model to Predict Poor Responders at Interim Assessment. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; He, X.; Qin, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhou, S.; Yang, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; et al. A new prognostic model including platelet/lymphocyte ratio and International Prognostic Score 3 for freedom from progression in patients with previously untreated advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 18, e486–e494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.W.; Chan, F.C.; Hong, F.; Rogic, S.; Tan, K.L.; Meissner, B.; Ben-Neriah, S.; Boyle, M.; Kridel, R.; Telenius, A.; et al. Gene expression-based model using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies predicts overall survival in advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luminari, S.; Donati, B.; Casali, M.; Valli, R.; Santi, R.; Puccini, B.; Kovalchuk, S.; Ruffini, A.; Fama, A.; Berti, V.; et al. A Gene Expression-based Model to Predict Metabolic Response After Two Courses of ABVD in Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.Q.; Gao, J.; Tao, H.; Wang, S.T.; Wang, F.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y.Q. The derived neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio are related to poor prognosis in Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Am. J. Blood Res. 2021, 11, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jakovic, L.R.; Mihaljevic, B.S.; Andjelic, B.M.; Bogdanovic, A.D.; Perunicic Jovanovic, M.D.; Babic, D.D.; Bumbasirevic, V.Z. Prognostic value of lymphocyte/monocyte ratio in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma: Correlation with International Prognostic Score and tumor associated macrophages. Leuk. Lymphoma 2016, 57, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, A.; Parrinello, N.L.; Vetro, C.; Chiarenza, A.; Cerchione, C.; Ippolito, M.; Palumbo, G.A.; Di Raimondo, F. Prognostic meaning of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and lymphocyte to monocyte ration (LMR) in newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated upfront with a PET-2 based strategy. Ann. Hematol. 2018, 97, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakos, C.I.; Charles, K.A.; McMillan, D.C.; Clarke, S.J. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e493–e503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Hua, Y.Q.; Wang, D.; Chen, L.Y.; Wu, C.J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L.M.; Chen, H. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.R.; Kim, A.S.; Choi, H.I.; Jung, J.H.; Park, J.Y.; Ko, H.J. Inflammatory markers for predicting overall survival in gastric cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, W.; Fang, X.; Wang, X. Prognostic significance of peripheral blood absolute lymphocyte count and derived neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with newly diagnosed extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 4243–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirili, C.; Paydas, S.; Kapukaya, T.K.; Yılmaz, A. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicting survival outcome in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Biomark. Med. 2019, 13, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ge, X.; Yuan, D.; Ding, M.; Qu, H.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Prognosis and complications of patients with primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Development and validation of the systemic inflammation response index-covered score. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9570–9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.Q.; Li, Y.H.; Lyu, B.; Gu, X.J.; Tian, M.X.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F. Effects of Prognostic Nutritional Index and Systemic Inflammatory Response Index on Short-Term Efficacy and Prognosis in Patients with Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. J. Exp. Hematol. 2025, 33, 1350–1357. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, R.; Maeoka, R.; Morimoto, T.; Nakazawa, T.; Morisaki, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Kotsugi, M.; Takeshima, Y.; Yamada, S.; Nishimura, F.; et al. Pre-treatment systemic inflammation response index and systemic immune inflammation in patients with primary central nerve system lymphoma as a useful prognostic indicator. J. Neurooncol. 2024, 168, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Deng, C.; Feng, Y.; Ma, F.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Hu, C.; Hou, T. Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) Independently Predicts Survival in Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients Treated with First-Generation EGFR-TKIs. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Kong, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J. Pretreatment Systemic Inflammation Response Index in Patients with Breast Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy as a Useful Prognostic Indicator. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 1543–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathas, S.; Hartmann, S.; Küppers, R. Hodgkin lymphoma: Pathology and biology. Semin. Hematol. 2016, 53, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, R.S.; Singh, G.; Singh, A.; Singh, P. Assessment of tumor microenvironment expression and clinical significance of immune inhibitory molecule CTLA-4, ligand B7-1, and tumor-infiltrating regulatory cells in Hodgkin lymphoma. J. Med. Life 2023, 16, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheson, B.D.; Fisher, R.I.; Barrington, S.F.; Cavalli, F.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zucca, E.; Lister, T.A. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Hodgkin lymphoma. In NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bachanova, V.; Connors, J.M. Hodgkin lymphoma in the elderly, pregnant, and HIV-infected. Semin. Hematol. 2016, 53, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, J.; Halthur, C.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Landgren, O.; Nygell, U.A.; Dickman, P.W.; Björkholm, M. Progress in Hodgkin lymphoma: A population-based study on patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973–2009. Blood 2012, 119, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Wu, P.; Wang, F.; Tao, H.; Shen, Q.; Wang, S.; Gong, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Causes of death and effect of non-cancer-specific death on rates of overall survival in adult classic Hodgkin lymphoma: A populated-based competing risk analysis. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böll, B.; Görgen, H.; Fuchs, M.; Pluetschow, A.; Eich, H.T.; Bargetzi, M.J.; Weidmann, E.; Junghanß, C.; Greil, R.; Scherpe, A.; et al. ABVD in older patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma treated within the German Hodgkin Study Group HD10 and HD11 trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1522–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evens, A.M.; Hong, F.; Gordon, L.I.; Fisher, R.I.; Bartlett, N.L.; Connors, J.M.; Gascoyne, R.D.; Wagner, H.; Gospodarowicz, M.; Cheson, B.D.; et al. The efficacy and tolerability of adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine and Stanford V in older Hodgkin lymphoma patients: A comprehensive analysis from the North American intergroup trial E2496. Br. J. Haematol. 2013, 161, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, A.A.; Aeppli, S.; Güsewell, S.; Bargetzi, M.; Caspar, C.; Brülisauer, D.; Ebnöther, M.; Fehr, M.; Fischer, N.; Ghilardi, G.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients over 60 years with Hodgkin lymphoma treated in Switzerland. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 39, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moccia, A.A.; Donaldson, J.; Chhanabhai, M.; Hoskins, P.J.; Klasa, R.J.; Savage, K.J.; Shenkier, T.N.; Slack, G.W.; Skinnider, B.; Gascoyne, R.D.; et al. International Prognostic Score in advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Altered utility in the modern era. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3383–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duminuco, A.; Del Fabro, V.; Santuccio, G.; Chiarenza, A.; Caruso, A.L.; Figuera, A.; Motta, G.; Fiumara, P.F.; Petronaci, A.; Palumbo, F.; et al. Hodgkin-Inflammatory-Based Model ME-IPS Is a New Inflammatory-Based Prognostic Model Calculated at Diagnosis: Results From a Real-Life Study. Eur. J. Haematol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodday, A.M.; Parsons, S.K.; Upshaw, J.N.; Friedberg, J.W.; Gallamini, A.; Hawkes, E.; Hodgson, D.; Johnson, P.; Link, B.K.; Mou, E.; et al. The Advanced-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma International Prognostic Index: Development and Validation of a Clinical Prediction Model From the HoLISTIC Consortium. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2076–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Aoki, T.; Tsuruyama, T.; Narumiya, S. Definition of Prostaglandin E2-EP2 Signals in the Colon Tumor Microenvironment That Amplify Inflammation and Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clatot, F.; Gouérant, S.; Mareschal, S.; Cornic, M.; Berghian, A.; Choussy, O.; El Ouakif, F.; François, A.; Bénard, M.; Ruminy, P.; et al. The gene expression profile of inflammatory, hypoxic and metabolic genes predicts the metastatic spread of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2014, 50, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.J.; McNamara, M.G.; Šeruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocaña, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.M.; Sloane, B.F. Cysteine cathepsins: Multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, J.A.; Pollard, J.W. Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanmee, T.; Ontong, P.; Konno, K.; Itano, N. Tumor-associated macrophages as major players in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers 2014, 6, 1670–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durgeau, A.; Virk, Y.; Corgnac, S.; Mami-Chouaib, F. Recent Advances in Targeting CD8 T-Cell Immunity for More Effective Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Hu, X.; Ren, S.; Li, X. Validation and comparison of prognostic value of different preoperative systemic inflammation indices in non-metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 2799–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SIRI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3.78 | ≥3.78 | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | p | ||

| Age (years) | <45 | 27 (37) | 15 (46.9) | 0.341 |

| ≥45 | 46 (63) | 17 (53.1) | ||

| Gender | Female | 32 (43.8) | 16 (50) | 0.559 |

| Male | 41 (56.2) | 16 (50) | ||

| Stage | 1 + 2 | 28 (38.4) | 6 (18.8) | 0.048 |

| 3 + 4 | 45 (61.6) | 26 (81.3) | ||

| ECOG PS | 0 + 1 | 72 (98.6) | 24 (75) | <0.001 |

| 2 + 3 | 1 (1.4) | 8 (25) | ||

| Bulky Disease | None | 70 (95.9) | 29 (90.6) | 0.366 |

| Yes | 3 (4.1) | 3 (9.4) | ||

| IPS 7 Score | Low | 49 (67.1) | 13 (40.6) | 0.002 |

| Intermediate | 22 (30.1) | 12 (37.5) | ||

| High | 2 (2.7) | 7 (21.9) | ||

| IPS 3 Score | 0 | 15 (20.5) | 5 (15.6) | 0.047 |

| 1 | 37 (50.7) | 9 (28.1) | ||

| 2 | 17 (23.3) | 16 (50) | ||

| 3 | 4 (5.5) | 2 (6.3) | ||

| Risk group | Early stage favorable risk | 9 (12.4) | 1 (3.1) | 0.117 |

| Early stage unfavorable risk | 19 (26) | 5 (15.6) | ||

| Advanced stage | 45 (61.6) | 26 (81.3) | ||

| Comorbidity | None | 46 (63) | 19 (59.4) | 0.724 |

| Yes | 27 (37) | 13 (40.6) | ||

| Treatment response | No/Partial response | 12 (16.4) | 14 (43.8) | 0.003 |

| Complete response | 61 (83.6) | 18 (56.3) | ||

| Relapse status | None | 61 (83.6) | 18 (56.3) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 12 (16.4) | 14 (43.8) | ||

| Survival status | Survivor | 60 (82.2) | 16 (50) | <0.001 |

| Non-survivor | 13 (17.8) | 16 (50) | ||

| SIRI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <3.78 | ≥3.78 | ||

| Mean ± SD Median (Min–Max) | Mean ± SD Median (Min–Max) | p | |

| Wbc (103/μL) | 6.82 (2.5–26.18) | 11.6 (4.1–28.8) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophil (103/μL) | 4.43 (1.2–19.75) | 9.1 (3.02–25.83) | <0.001 |

| Monocyte (103/μL) | 0.57 (0.03–2.47) | 0.96 (0.21–4.03) | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte (103/(μL) | 1.78 (0.35–12.17) | 1.51 (0.27–5.65) | 0.035 |

| Hemoglobin (gr/dL) | 12.9 ± 1.8 | 11.5 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| Platelet (103/μL) | 297 ± 105 | 367± 161 | 0.029 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 (3.2–5.1) | 3.8 (2.4–4.5) | 0.001 |

| D. bilirubine (mg/dL) | 0.1 (0–0.8) | 0.1 (0.1–0.7) | 0.096 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 19 (2–111) | 50 (9–110) | <0.001 |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | HR | 95% CI for HR | p | HR | 95% CI for HR | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender | 0.168 | 1.796 | 0.781 | 4.131 | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.939 | 0.970 | 0.445 | 2.114 | ||||

| Stage | 0.082 | 2.020 | 0.916 | 4.454 | 0.440 | 1.415 | 0.587 | 3.410 |

| Hemoglobin(gr/dL) | 0.004 | 3.498 | 1.507 | 8.117 | 0.159 | 1.986 | 0.764 | 5.162 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.055 | 0.469 | 0.217 | 1.015 | 0.688 | 0.835 | 0.347 | 2.011 |

| Wbc (103/μL) | 0.991 | 0.992 | 0.234 | 4.201 | ||||

| Lymphocyte (103/μL) | 0.411 | 1.834 | 0.432 | 7.789 | ||||

| IPS 7 Score (intermediate vs. low) | 0.069 | 2.258 | 0.938 | 5.432 | ||||

| IPS 7 Score (high vs. low) | 0.000 | 6.521 | 2.361 | 18.011 | ||||

| SIRI | 0.002 | 3.359 | 1.548 | 7.293 | 0.033 | 2.516 | 1.077 | 5.881 |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | HR | 95% CI for HR | p | HR | 95% CI for HR | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender | 0.655 | 1.184 | 0.565 | 2.480 | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.025 | 2.800 | 1.139 | 6.882 | 0.016 | 3.155 | 1.241 | 8.018 |

| Stage | 0.086 | 1.929 | 0.911 | 4.087 | 0.770 | 1.135 | 0.485 | 2.657 |

| Hemoglobin(gr/dL) | 0.001 | 3.541 | 1.642 | 7.637 | 0.127 | 2.038 | 0.816 | 5.090 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.001 | 0.288 | 0.133 | 0.619 | 0.175 | 0.537 | 0.218 | 1.318 |

| Wbc (103/μL) | 0.631 | 1.340 | 0.405 | 4.430 | ||||

| Lymphocyte (103/μL) | 0.010 | 4.084 | 1.408 | 11.840 | 0.414 | 1.674 | 0.486 | 5.773 |

| IPS 7 Score (intermediate vs. low) | 0.000 | 6.237 | 2.456 | 15.838 | ||||

| IPS 7 Score (high vs. low) | 0.000 | 9.356 | 3.013 | 29.048 | ||||

| SIRI | 0.001 | 3.316 | 1.588 | 6.923 | 0.012 | 2.731 | 1.251 | 5.964 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ilkkilic, K.; Sen, B. Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma. Medicina 2026, 62, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020264

Ilkkilic K, Sen B. Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020264

Chicago/Turabian StyleIlkkilic, Kadir, and Bayram Sen. 2026. "Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma" Medicina 62, no. 2: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020264

APA StyleIlkkilic, K., & Sen, B. (2026). Prognostic Significance of the Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) in Patients with Hodgkin Lymphoma. Medicina, 62(2), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020264