How Can We Prevent Postoperative Kyphosis in Cervical Laminoplasty?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Surgical Procedure

2.2. Independent Variables

2.2.1. Preoperative Demographic Independent Variables

- Age

- Sex

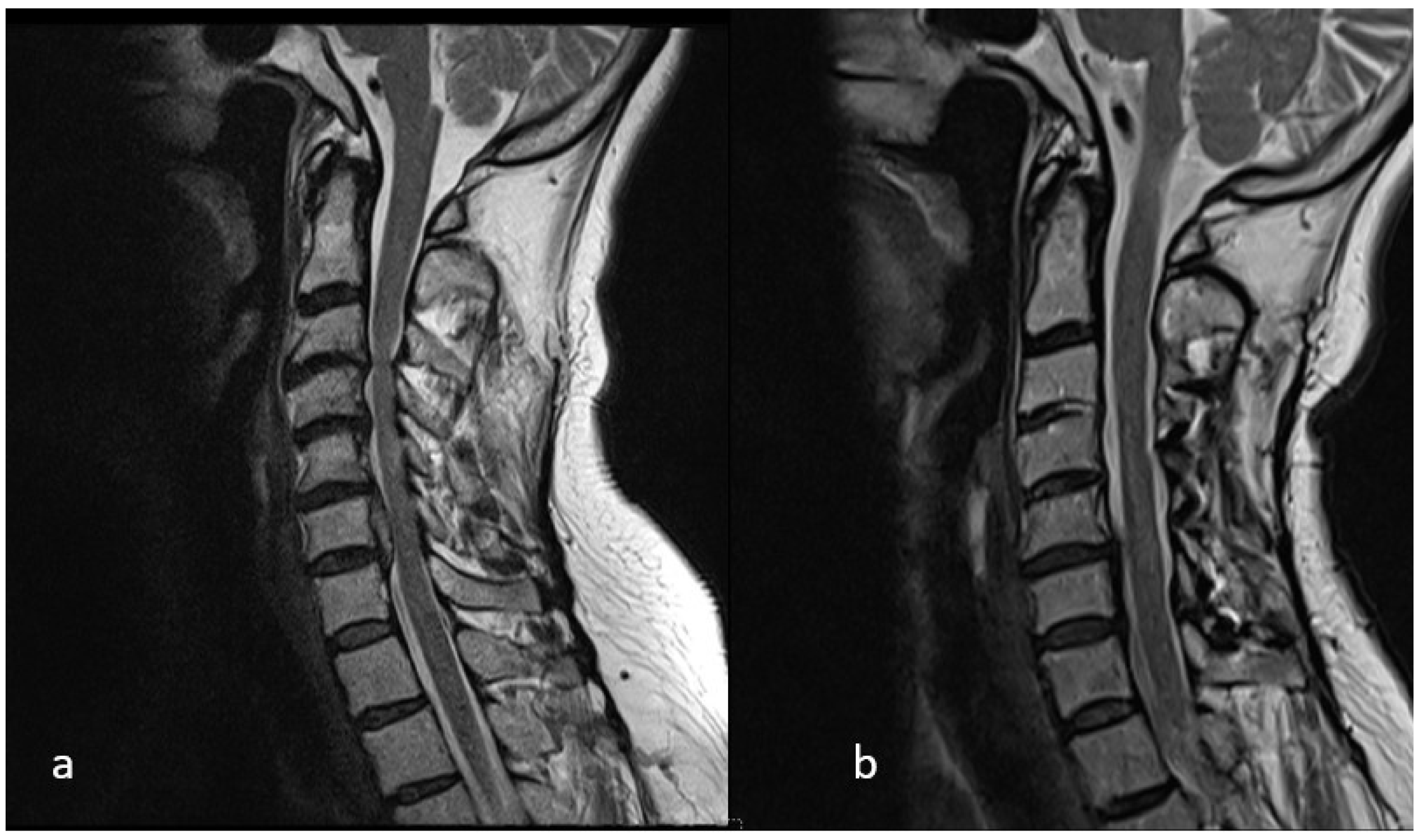

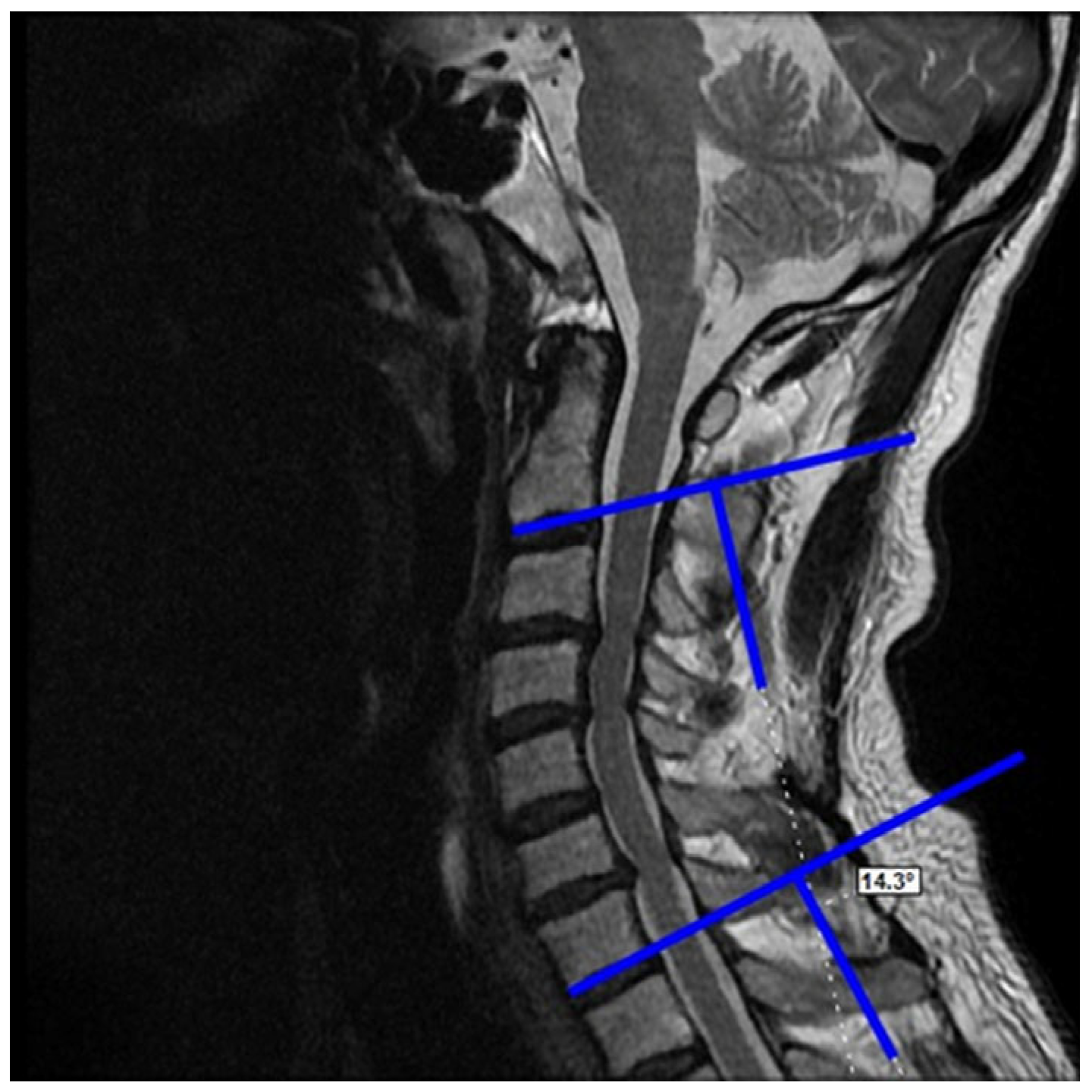

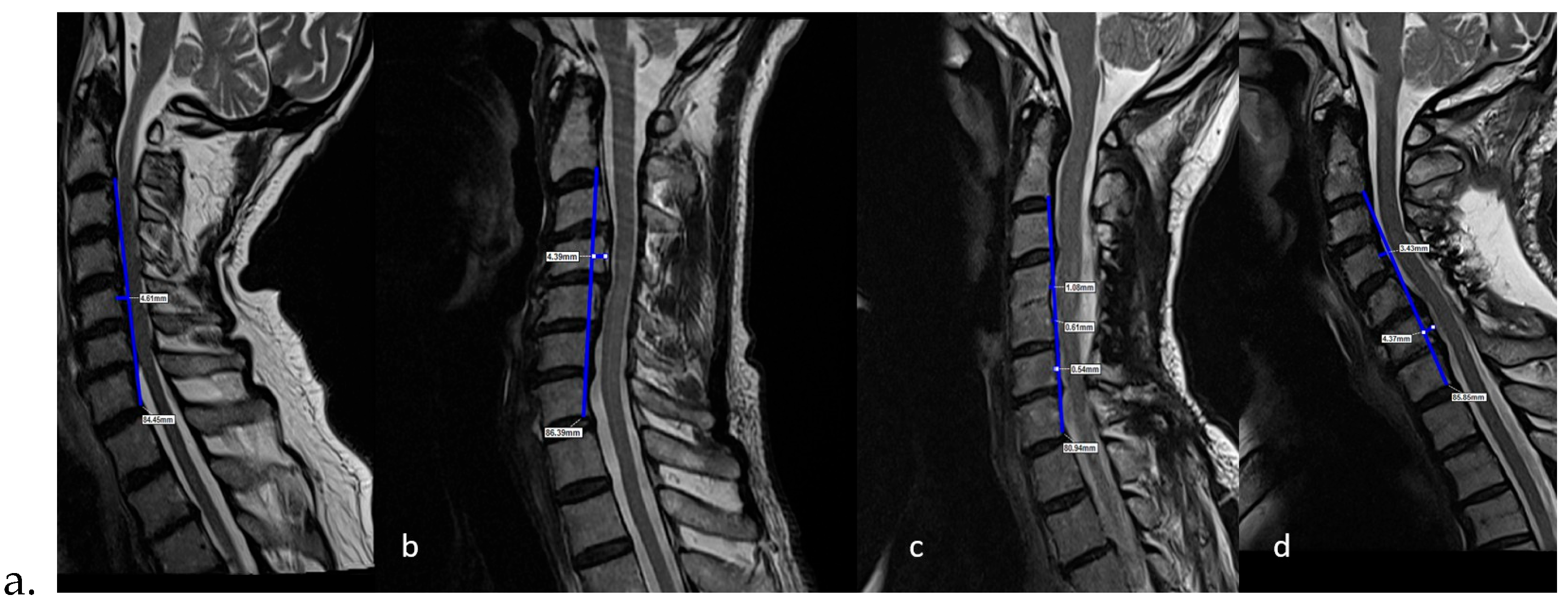

2.2.2. Preoperative Radiological Independent Variables

2.2.3. Intraoperatively Identified Independent Variables

- Lamina lifting side

- Total number of levels applied laminoplasty

- Whether laminoplasty performed on C3 or not

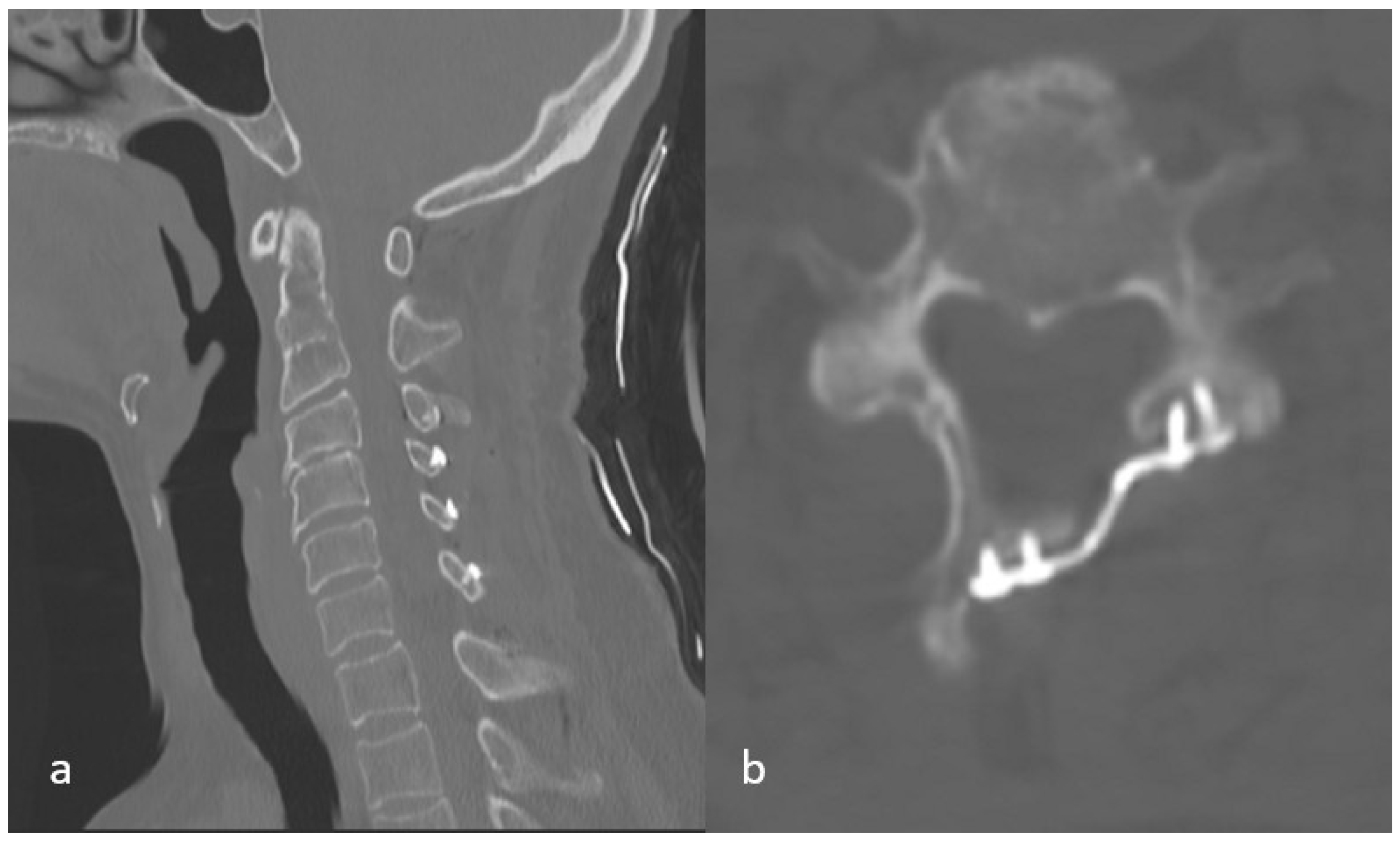

2.2.4. Independent Variables Detected on Early Postoperative CT Imaging

- Whether there is a lamina fracture or not

- Total number of lamina fractures

- Whether or not there is a fracture at the highest level where laminoplasty was performed

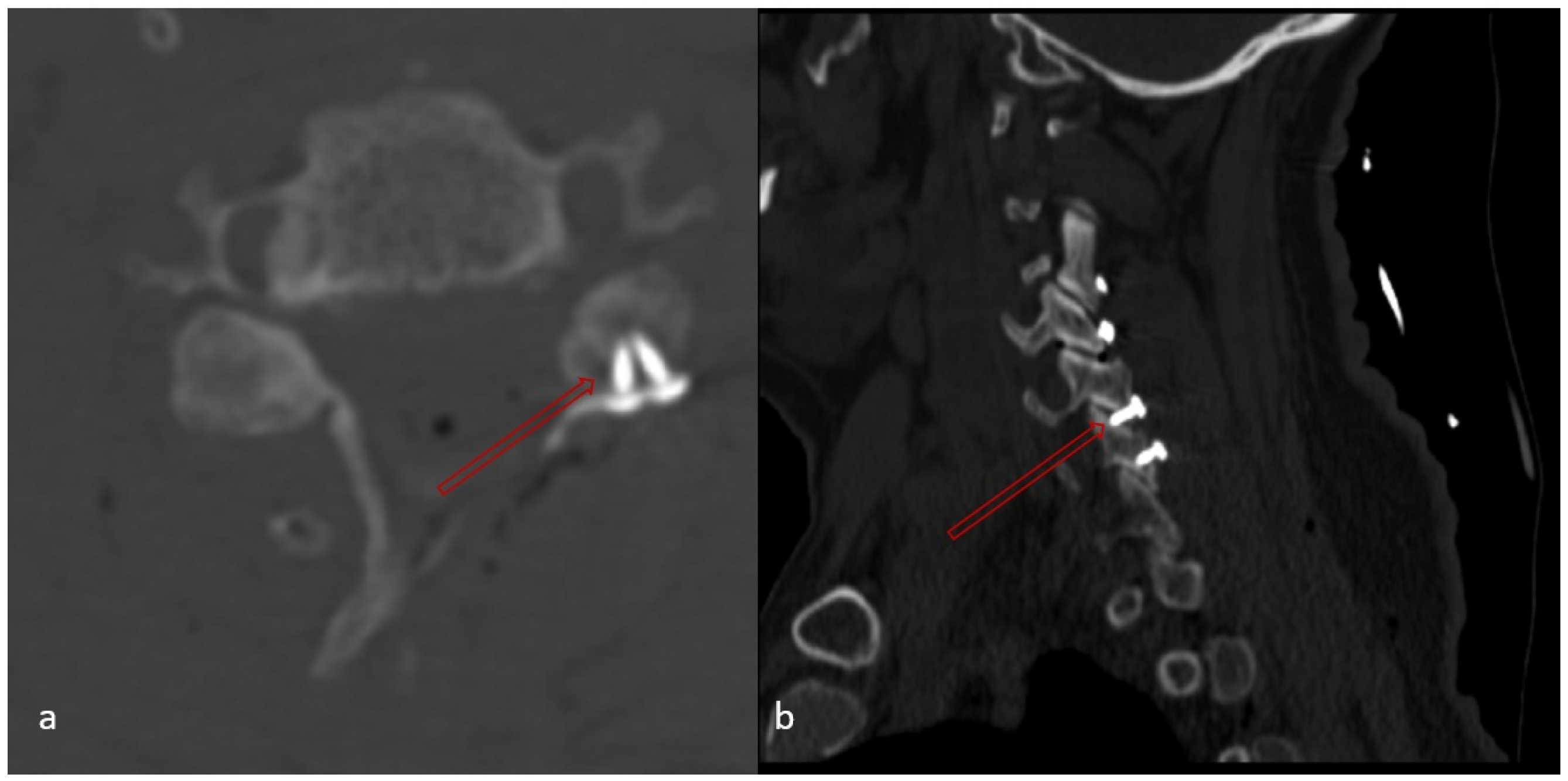

- Whether any of the screw placed in the lateral mass causes facet joint disturbance or not (Figure 6),

- Number of facet disturbance,

- Whether there is uppermost facet disturbance or not,

- Whether there is lowermost facet disturbance or not

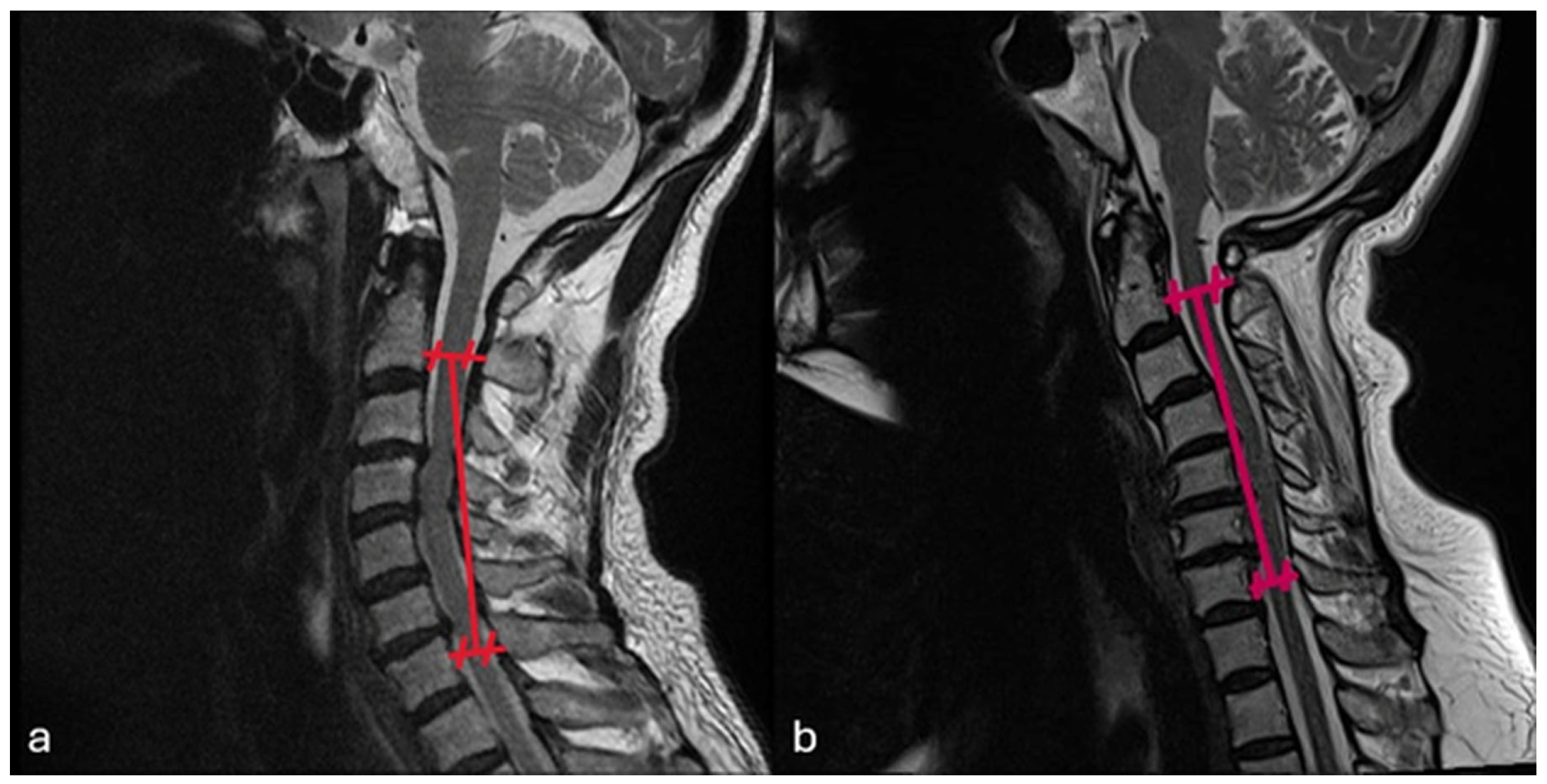

2.3. Dependent Variables (Radiological)

- Postoperative last control C2–C7 Cobb angle

- Postoperative last control cervical alignment

- Postoperative last control K-line

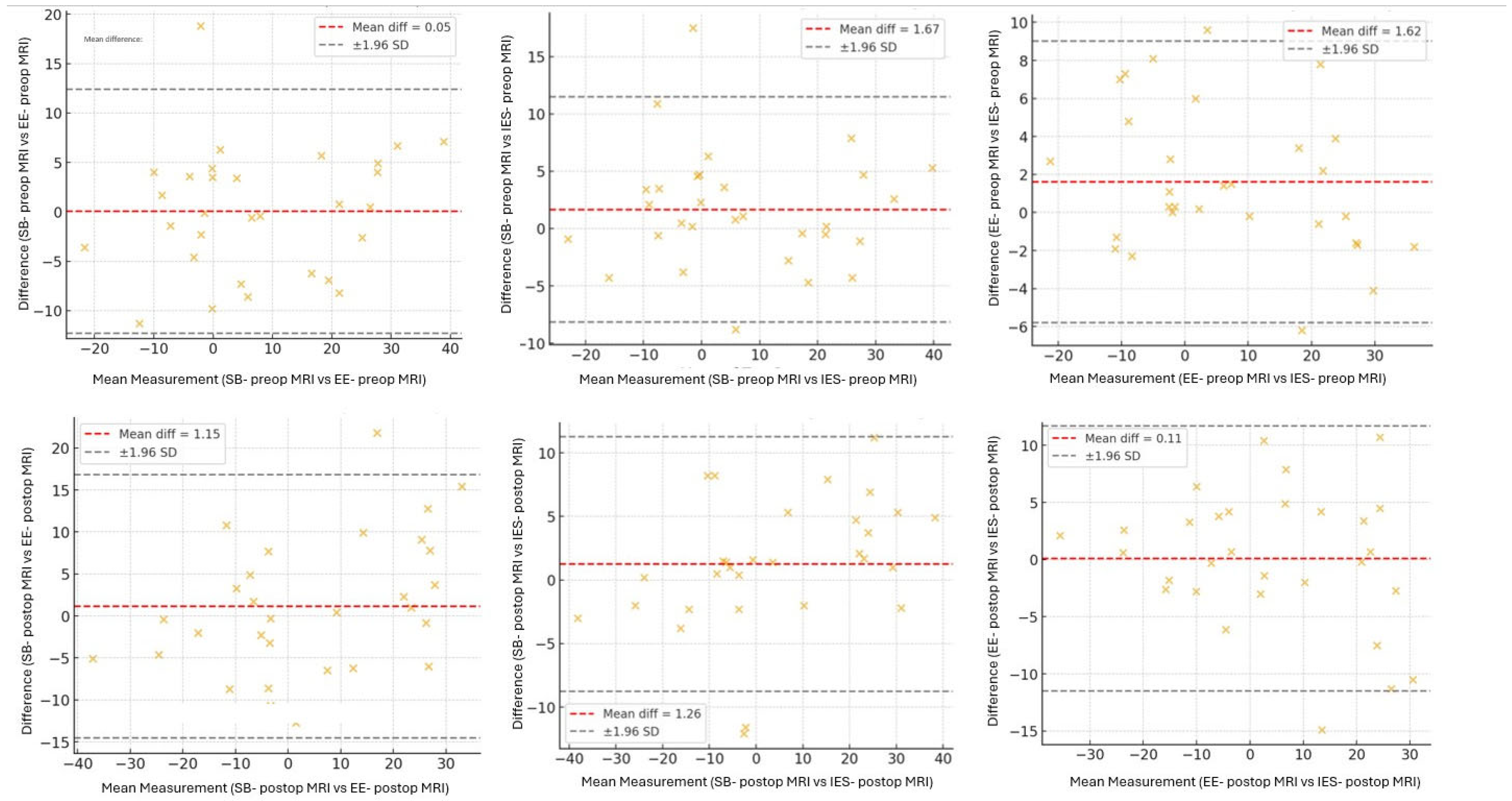

2.4. Observer Agreement

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Observer Reliability

3.2. Study Population

3.3. Relationships Between Independent and Dependent Variables

3.3.1. Preoperative Demographic Independent Variables vs. Dependent Variables

3.3.2. Preoperative Radiological Independent Variables vs. Dependent Variables

Preoperative C2–C7 Cobb Angle vs. Postoperative Last Control C2–C7 Cobb Angle

Preoperative Cervical Alignment Category vs. Postoperative Cervical Alignment Category

Preoperative K-Line vs. Postoperative K-Line

3.3.3. Intraoperatively Identified Independent Variables vs. Dependent Variables

Whether or Not Laminoplasty Performed on C3 vs. Postoperative Last Control C2–C7 Cobb Angle

3.3.4. Independent Variables Detected on Early Postoperative CT Imaging vs. Dependent Variables

Whether There Is a Lamina Fracture vs. Postoperative Last Control C2–C7 Cobb Angle

Whether or Not There Is a Uppermost Lamina Fracture vs. Postoperative Last Control C2–C7 Cobb Angle

Whether or Not There Is Uppermost Facet Disturbance vs. Postoperative Last Control C2–C7 Cobb Angle

3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Uppermost Facet Disturbance: The Key Independent Predictor

4.2. Role of Preoperative Lordosis

4.3. Uppermost Lamina Fracture: Loss of Significance in Multivariate Analysis

4.4. Role of C3 Involvement

4.5. Clinical Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CSM | Cervical spondylotic myelopathy |

| OPLL | Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

References

- Gembruch, O.; Jabbarli, R.; Rashidi, A.; Chihi, M.; El Hindy, N.; Wetter, A.; Hütter, B.O.; Sure, U.; Dammann, P.; Özkan, N. Degenerative cervical myelopathy in higher-aged patients: How do they benefit from surgery? J. Clin. Med. 2019, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, A.; Tetreault, L.; Singh, A.; Karadimas, S.K.; Fehlings, M.G. Degenerative cervical myelopathy: Epidemiology, genetics, and pathogenesis. Spine 2015, 40, E675–E693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, H.; Kim, H.-C.; Kim, T.W.; An, S.B.; Shin, D.A.; Yi, S.; Kim, K.N.; Yoon, D.H.; Borkar, S.A.; Son, D.W.; et al. Prediction of angular kyphosis after cervical laminoplasty using radiologic measurements. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 85, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Endo, K.; Nishimura, H.; Suzuki, H.; Sawaji, Y.; Takamatsu, T.; Seki, T.; Murata, K.; Konishi, T.; Yamamoto, K. Cervical kyphotic deformity after laminoplasty in patients with cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament with normal sagittal spinal alignment. Spine Surg. Relat. Res. 2018, 2, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, K.; Abumi, K.; Ito, M.; Shono, Y.; Kaneda, K.; Fujiya, M. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine 2003, 28, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, K.-S.; Kim, K.-T.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Lim, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-S. Sagittal alignment of the cervical spine after the laminoplasty. Spine 2007, 32, E656–E660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.Y.; Shah, S.; Green, B.A. Clinical outcomes following cervical laminoplasty for 204 patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Surg. Neurol. 2004, 62, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaura, H.; Hosono, N.; Mukai, Y.; Oshima, K.; Iwasaki, M.; Yoshikawa, H. Preservation of the nuchal ligament plays an important role in preventing unfavorable radiologic changes after laminoplasty. Clin. Spine Surg. 2008, 21, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.-Y.; Shin, M.-H.; Kim, J.-T. Impact of C3 Involvement on Postoperative Kyphosis Following Cervical Laminoplasty: A Comparison Between High and Low T1 Slope. World Neurosurg. 2022, 167, e1084–e1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; He, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, B.; Gong, Q.; Li, T.; Liu, H. Cervical Alignment and Range of Motion Change after Anterior 3-Level Hybrid Surgery Compared with Cervical Laminoplasty: A Matched Cohort Study. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 16, 1893–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Yang, L.; Shen, Y. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with kyphotic deformity after laminoplasty in cervical spondylotic myelopathy patients without preoperative kyphotic alignment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Li, T.; Gong, Q.; Song, Y.; Liu, H. Facet joint disturbance induced by miniscrews in plated cervical laminoplasty: Dose it influence the clinical and radiologic outcomes? Medicine 2016, 95, e4666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, W.-K.; Seo, I.; Na, S.-B.; Choi, Y.-S.; Choi, J.-Y. Radiological analysis of minimal safe distance and optimal screw angle to avoid facet violation in open-door laminoplasty using precontoured plate. J. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 25, 2309499017736562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Rong, X.; Gong, Q.; Li, T.; Song, Y.; Liu, H. Optimal area of lateral mass mini-screws implanted in plated cervical laminoplasty: A radiography anatomy study. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machino, M.; Ando, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Morozumi, M.; Tanaka, S.; Kanbara, S.; Ito, S.; Inoue, T.; Ito, K.; Kato, F.; et al. Postoperative kyphosis in cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Cut-off preoperative angle for predicting the postlaminoplasty kyphosis. Spine 2020, 45, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-H.; Park, S.; Cho, J.H.; Hwang, C.J.; Yang, J.J.; Lee, C.S. Risk factors for postoperative loss of lordosis, cervical kyphosis, and sagittal imbalance after cervical laminoplasty. World Neurosurg. 2023, 180, e324–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-H.; Kim, H.; Lee, C.S.; Hwang, C.-J.; Cho, J.-H.; Cho, S.K. Clinical and radiographic outcomes following hinge fracture during open-door cervical laminoplasty. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 43, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, K.; Seichi, A.; Akune, T.; Kawamura, N.; Kawaguchi, H.; Nakamura, K. Can laminoplasty maintain the cervical alignment even when the C2 lamina is contained? Spine 2005, 30, 1294–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevin, I.E.; Bozdag, S.; Erisken, E.; Sucu, H.K. Comparison of Radiography with Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Measurement of Cervical Lordosis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Imaging | Interobserver Reliability * | Intraobserver Reliability * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB | IES | EE | ||

| Preop-MRI | 0.981 | 0.940 | 0.910 | 0.946 |

| Postop-MRI | 0.940 | 0.951 | 0.903 | 0.910 |

| Preoperative MRI Alignment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lordosis | Straight | Sigmoidal | Kyphosis | Total | |

| Postoperative MRI Alignment | |||||

| Lordosis | 29 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 32 |

| Straight | 6 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 23 |

| Sigmoidal | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Kyphosis | 1 | 7 | 0 | 13 | 21 |

| Total | 36 | 23 | 1 | 18 | 78 |

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97–1.05 | 0.723 |

| Gender (female) | 0.52 | 0.21–1.29 | 0.160 |

| Preop Cobb angle | 1.01 | 0.98–1.5 | 0.321 |

| Preop alignment (lordosis) | 0.93 | 0.62–1.38 | 0.726 |

| Level number of laminoplasty | 1.72 | 0.92–3.23 | 0.091 |

| C3 laminoplasty | 2.36 | 0.79–7.06 | 0.124 |

| Lamina fracture | 1.86 | 0.74–4.60 | 0.182 |

| Lamina fracture at the top level | 2.80 | 0.89–8.71 | 0.075 |

| Lamina fracture at the lowest level | 1.63 | 0.54–4.93 | 0.382 |

| Facet disturbance | 3.00 | 0.89–10.00 | 0.073 |

| Facet disturbance at the top level | 2.73 | 1.01–7.34 | 0.046 |

| Facet disturbance at the lowest level | 2.53 | 1.00–6.37 | 0.048 |

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level number of laminoplasty | 1.24 | 0.78–2.11 | 0.297 |

| Lamina fracture at the top level | 1.63 | 0.56–4.83 | 0360 |

| Facet disturbance | 1.18 | 0.40–3.42 | 0.761 |

| Facet disturbance at the top level | 4.62 | 1.07–19.3 | 0.039 |

| Facet disturbance at the lowest level | 1.72 | 0.65–4.51 | 0.273 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Erisken, E.; Bozdag, S.; Sevin, I.E.; Sucu, H.K. How Can We Prevent Postoperative Kyphosis in Cervical Laminoplasty? Medicina 2026, 62, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010058

Erisken E, Bozdag S, Sevin IE, Sucu HK. How Can We Prevent Postoperative Kyphosis in Cervical Laminoplasty? Medicina. 2026; 62(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleErisken, Efecan, Selin Bozdag, Ismail Ertan Sevin, and Hasan Kamil Sucu. 2026. "How Can We Prevent Postoperative Kyphosis in Cervical Laminoplasty?" Medicina 62, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010058

APA StyleErisken, E., Bozdag, S., Sevin, I. E., & Sucu, H. K. (2026). How Can We Prevent Postoperative Kyphosis in Cervical Laminoplasty? Medicina, 62(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010058