Potential Associations Between CT-Derived Muscle Indices and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

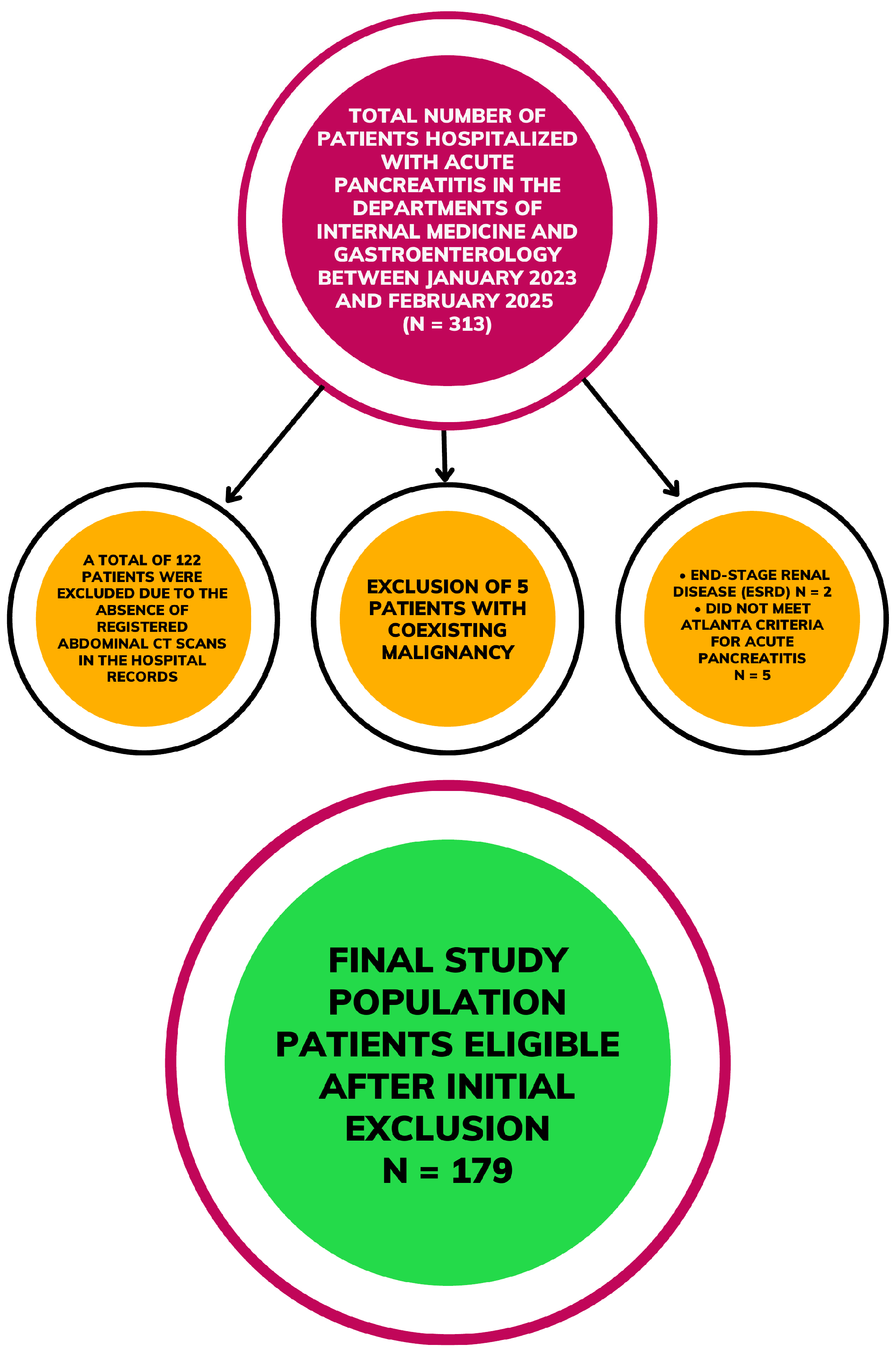

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Pancreatitis Classification and Patient Selection

2.3. Patient’s Characteristics, Laboratory Measurements, and CT Imaging

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics and Clinical Features

3.2. Correlation Analyses Between Muscle Indices and Clinical–Biochemical Parameters

3.3. Correlation Analyses Stratified by Sex

3.4. Correlation Analyses in Patients Aged 65 Years and Older

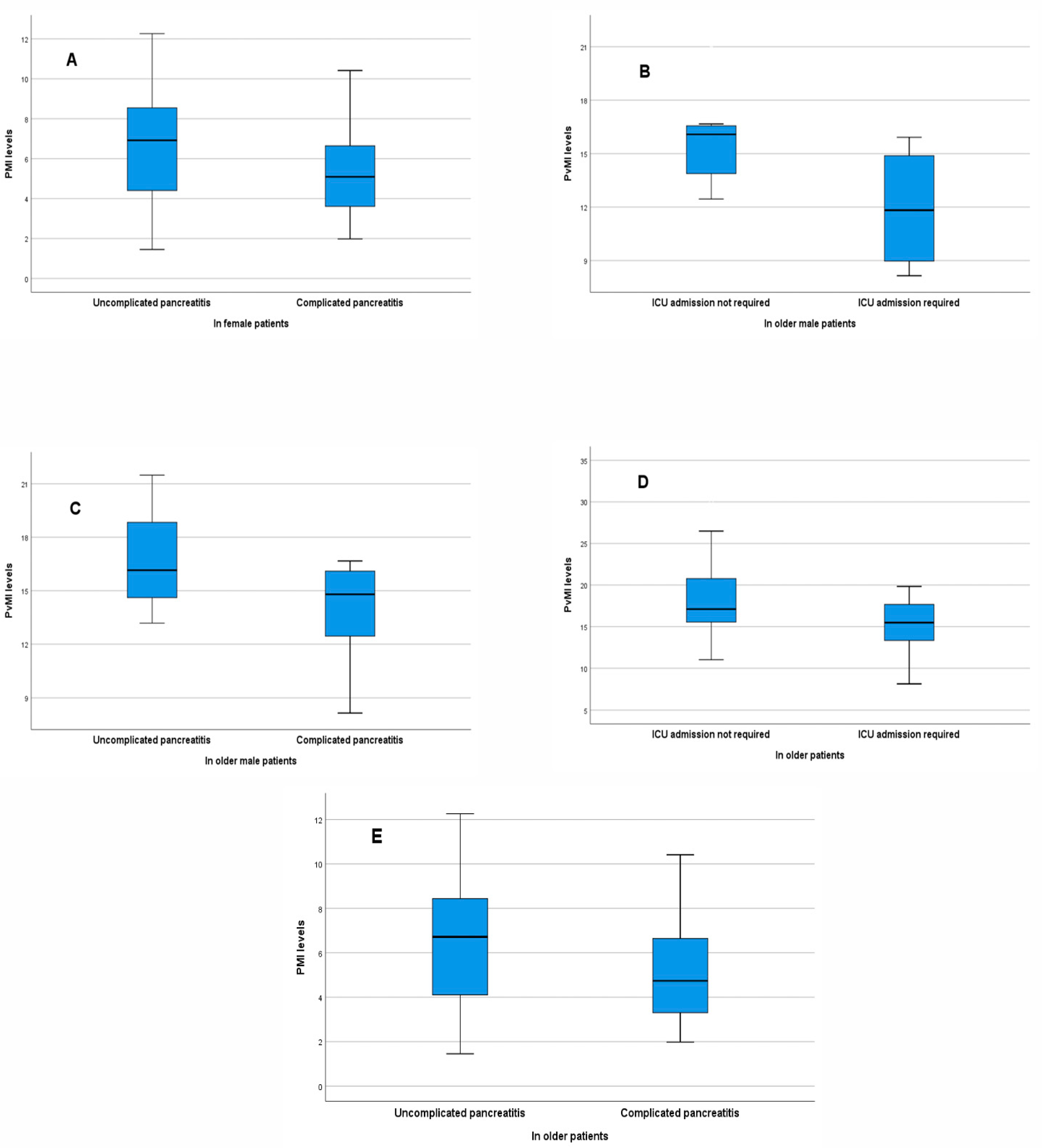

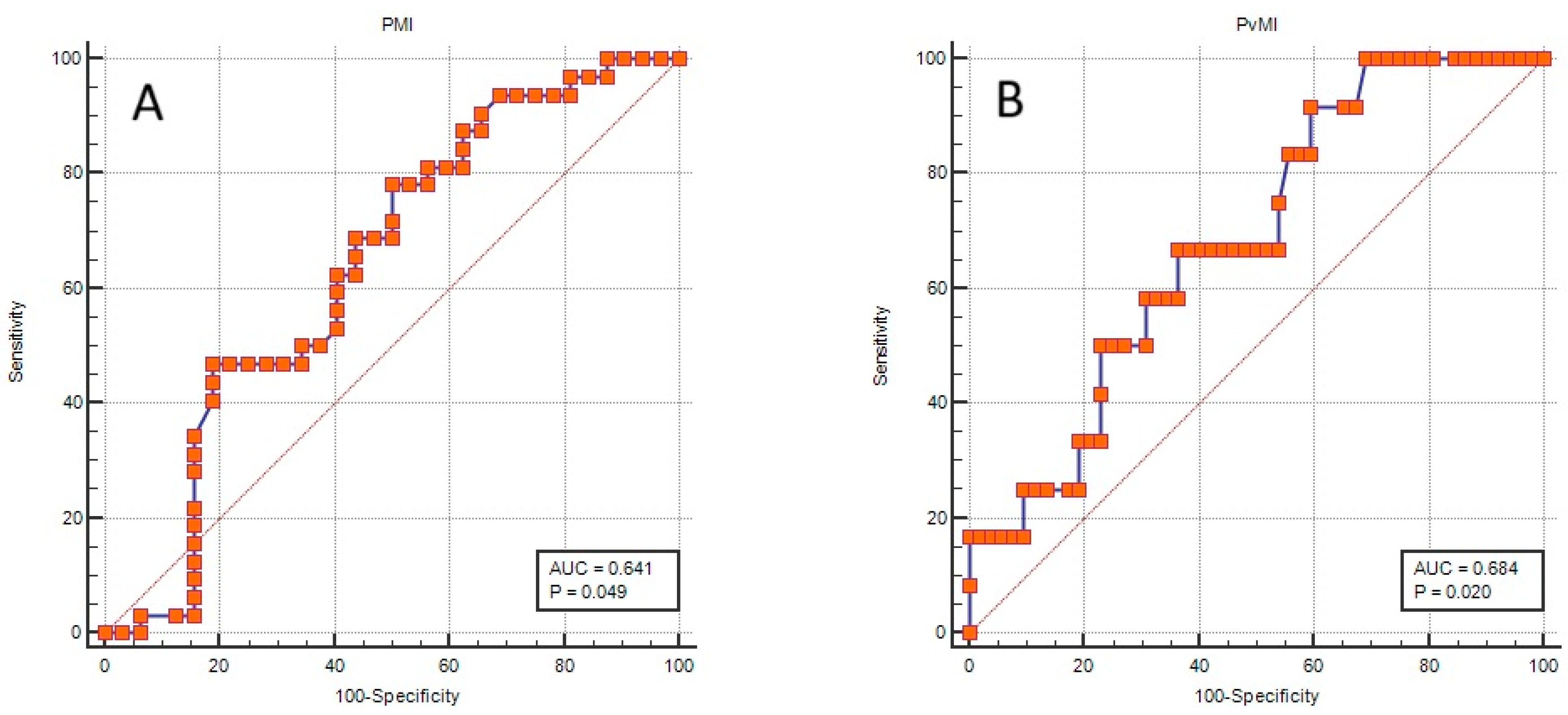

3.5. Association of Muscle Indices with Complicated Disease Course and Intensive Care Requirement

3.6. Comparisons of Muscle Indices According to Clinical Outcomes in Patients Aged 65 Years and Older

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AP | Acute pancreatitis |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| BISAP | Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis |

| CCI | Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| L3 | Third lumbar vertebral level |

| PMI | Psoas muscle index |

| PvMI | Paravertebral muscle index |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Siregar, G.A.; Siregar, G.P. Management of severe acute pancreatitis. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3319–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, A.Y.; Tan, M.L.; Wu, L.M.; Asrani, V.M.; Windsor, J.A.; Yadav, D.; Petrov, M.S. Global incidence and mortality of pancreatic diseases: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of population-based cohort studies. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larvin, M.; Mcmahon, M. APACHE-II score for assessment and monitoring of acute pancreatitis. Lancet 1989, 334, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.K.; Wu, B.U.; Bollen, T.L.; Repas, K.; Maurer, R.; Johannes, R.S.; Mortele, K.J.; Conwell, D.L.; A Banks, P. A prospective evaluation of the bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis score in assessing mortality and intermediate markers of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 104, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, F. Associations between sarcopenia (defined by low muscle mass), inflammatory markers, and all-cause mortality in older adults: Mediation analyses in a large U.S. NHANES community sample, 1999–2006. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1515839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodge, G.A.; Goenka, U.; Jajodia, S.; Agarwal, R.; Afzalpurkar, S.; Roy, A.; Goenka, M.K. Psoas Muscle Index: A Simple and Reliable Method of Sarcopenia Assessment on Computed Tomography Scan in Chronic Liver Disease and its Impact on Mortality. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2023, 13, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesen, S.S.; Büyükuslu, A.; Køhler, M.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Drewes, A.M. Sarcopenia associates with increased hospitalization rates and reduced survival in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2019, 19, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundred, J.; Thakkar, R.G.; Pandanaboyana, S. Systematic review of sarcopenia in chronic pancreatitis: Prevalence, impact on surgical outcomes, and survival. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 16, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, K.D.R.; Patel, H.; Downie, E. A systematic review on the prognostic role of radiologically-proven sarcopenia on the clinical outcomes of patients with acute pancreatitis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, P.A.; Bollen, T.L.; Dervenis, C.; Gooszen, H.G.; Johnson, C.D.; Sarr, M.G.; Tsiotos, G.G.; Vege, S.S. Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: Revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut 2013, 62, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, N.H.; Shin, C. Paravertebral Muscles as Indexes of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity: Comparison with Imaging and Muscle Function Indexes and Impact on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2021, 216, 1596–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Li, P.; Xing, Q.; Jiang, H.; Sui, H. Cutoff Value of Psoas Muscle Area as Reduced Muscle Mass and Its Association with Acute Pancreatitis in China. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 2733–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, N.; Li, X.; Huang, P.; Wang, L.; Cheng, X.; Yu, A. Percentiles for paraspinal muscle parameters at the L3 vertebra level in patients undergoing lumbar computed tomography scanning. Acta Radiol. 2023, 64, 2152–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, H.; Li, B.; Couris, C.M.; Fushimi, K.; Graham, P.; Hider, P.; Januel, J.-M.; Sundararajan, V. Updating and validating the charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 173, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.F.; Tariq, A.; Chandra, S. Acute pancreatitis. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 2 August 2025]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482468/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Kilic, G.S.; Tahtaci, M.; Yagmur, F.; Akin, F.E.; Yurekli, O.T.; Ersoy, O. Influence of sarcopenia as determined by bioelectrical impedance analysis in acute pancreatitis. Medicine 2024, 103, e40868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirzhner, A.; Rossels, A.; Sapojnik, D.; Zaharoni, H.; Cohen, R.; Lin, G.; Schiller, T. Psoas muscle index and density as prognostic predictors in patients hospitalized with acute pancreatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhu, P.; Jin, T.; Li, L.; Lin, Z.; Shi, N.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Q.; et al. The Clinical characteristics and outcomes of acute pancreatitis are different in elderly patients: A single-center study over a 6-year period. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çalim, A. Clinical evaluation of the severity of acute pancreatitis in elderly patients. Acta Gastro Enterol. Belg. 2023, 86, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Du, Y.; Xiang, C.; Li, X.; Zhou, W. Age-period-cohort analysis of pancreatitis epidemiological trends from 1990 to 2019 and forecasts for 2044: A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1118888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | All Patients n = 179 | Non-Complicated AP n = 108 | Complicated AP n = 71 | p-Value | Without ICU Admission n = 159 | With ICU Admission n = 20 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Characteristics | |||||||

| • Age, years | 58 (19–97) | 54 (19–97) | 63 (21–90) | 0.006 | 57 (19–97) | 68 (26–90) | 0.005 |

| • Gender, female | 95 (53.1) | 59 (54.6) | 36 (50.7) | 0.607 | 85 (53.5) | 10 (50.0) | 0.770 |

| • BMI, kg/m2 | 25.71 (19.05–44.62) | 25.84 (19.05–44.62) | 25.71 (20.55–38.06) | 0.892 | 25.71 (19.05–44.62) | 25.69 (20.55–37.87) | 0.491 |

| • Length of stay, days | 7 (3–40) | 6 (4–13) | 10 (3–40) | <0.001 | 7 (4–24) | 13 (3–40) | <0.001 |

| • Number of AP attacks | 1 (1–5) | 1 (1–5) | 1 (1–3) | 0.859 | 1 (1–5) | 1 (1–5) | 0.009 |

| • CCI | 0 (0–4) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–4) | 0.115 | 0 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | <0.001 |

| Etiology | |||||||

| • Non-biliary | 108 (60.3) | 72 (66.7) | 36 (50.7) | 0.033 | 97 (61.0) | 11 (55.0) | 0.605 |

| • Biliary | 71 (39.7) | 36 (33.3) | 35 (49.3) | 62 (39.0) | 9 (45.0) | ||

| Disease severity | |||||||

| • Mild | 108 (60.3) | 102 (94.4) | 6 (8.5) | <0.001 | 106 (66.7) | 2 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| • Moderate | 54 (30.2) | 5 (4.6) | 49 (69.0) | 47 (29.6) | 7 (35.0) | ||

| • Severe | 17 (9.5) | 1 (0.9) | 16 (22.5) | 6 (3.8) | 11 (55.0) | ||

| ICU need | 20 (11.2) | 3 (2.8) | 17 (23.9) | <0.001 | |||

| Complication rate | 71 (39.7) | - | - | - | 54 (34.0) | 17 (85.0) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 3 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.2) | 0.061 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Muscle measurements | |||||||

| • PMI, cm2/m2 | 5.51 (1.45–12.26) | 5.53 (1.45–12.26) | 5.51 (1.98–10.73) | 0.331 | 5.51 (1.45–12.26) | 5.74 (2.29–9.77) | 0.608 |

| • PvMI, cm2/m2 | 16.9 ± 4.12 | 17.07 ± 4.05 | 16.66 ± 4.24 | 0.514 | 17 ± 4.11 | 16.17 ± 4.22 | 0.400 |

| • Patients with low PMA, n (%) | 43 (24) | 28 (25.9) | 15 (21.1) | 0.462 | 39 (24.5) | 4 (20.0) | 0.786 |

| • Patients with low PvMA, n (%) | 67 (37.4) | 38 (35.2) | 29 (40.8) | 0.444 | 59 (37.1) | 8 (40.0) | 0.801 |

| Laboratory values | |||||||

| • WBC, 103/µL | 10.75 (2.1–39.54) | 10.17 (3.3–21.61) | 13.33 (2.1–39.54) | <0.001 | 10.62 (2.1–21.61) | 19.31 (6–39.54) | <0.001 |

| • PLT, 103/µL | 251 (85–605) | 249 (100–434) | 251 (85–605) | 0.378 | 249 (85–495) | 257 (100–605) | 0.636 |

| • HB, g/dL | 13.94 ± 2.08 | 13.74 ± 1.99 | 14.23 ± 2.19 | 0.125 | 13.94 ± 2.03 | 13.95 ± 2.51 | 0.985 |

| • ALT, U/L | 43 (5–1498) | 34 (5–696) | 58 (9–1498) | 0.144 | 37 (5–729) | 120.5 (19–1498) | 0.015 |

| • AST, U/L | 46 (5–3647) | 36 (5–1612) | 75 (5–3647) | 0.169 | 38 (5–1612) | 191.5 (17–3647) | 0.005 |

| • ALP, U/L | 93 (32–663) | 89 (32–631) | 109 (40–663) | 0.145 | 90 (32–631) | 141 (44–663) | 0.010 |

| • GGT, U/L | 65 (4–1542) | 50 (4–1204) | 133 (8–1542) | 0.023 | 55 (4–1204) | 225 (14–1542) | 0.006 |

| • Amylase, U/L | 625 (8–4618) | 473.5 (8–4618) | 884 (28–4228) | 0.029 | 603 (8–4618) | 793.5 (28–4228) | 0.716 |

| • Lipase, U/L | 1291 (15–12,701) | 1165 (24–12,701) | 1458 (15–10,204) | 0.098 | 1262 (24–12,701) | 1423.5 (15–9461) | 0.887 |

| • Glucose, mg/dL | 118 (54–474) | 107 (58–474) | 131 (54–406) | <0.001 | 116 (54–474) | 149 (60–406) | 0.050 |

| • Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.39–3.9) | 0.76 (0.41–3.9) | 0.85 (0.39–2.48) | 0.053 | 0.77 (0.41–3.9) | 1 (0.39–2.48) | <0.001 |

| • Total Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.7 (0.14–7) | 0.59 (0.14–5) | 0.85 (0.17–7) | 0.014 | 0.64 (0.14–7) | 1.05 (0.37–6.92) | 0.015 |

| • Direct Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.23 (0.09–4.96) | 0.2 (0.09–3.14) | 0.3 (0.09–4.96) | 0.038 | 0.21 (0.09–4.96) | 0.46 (0.09–4.63) | 0.024 |

| • Albumin, g/L | 40 (19–49) | 41 (27–49) | 40 (19–49) | 0.338 | 41 (24–49) | 37.5 (19–46) | 0.018 |

| • Calcium, mg/dL | 8.6 (6.3–10.7) | 8.6 (6.9–9.9) | 8.5 (6.3–10.7) | 0.442 | 8.6 (6.8–10.7) | 8.25 (6.3–10.4) | 0.038 |

| • Triglyceride, mg/dL | 104 (38–3421) | 100 (38–3421) | 120 (38–1257) | 0.028 | 101 (38–3421) | 158 (55–1256) | 0.050 |

| • CRP, mg/L | 15.3 (0.6–290) | 12 (0.6–105) | 23.42 (0.6–290) | 0.003 | 13.76 (0.6–290) | 47.19 (4.6–247) | 0.002 |

| • Procalcitonin, µg/L | 0.1 (0.01–100) | 0.06 (0.01–92) | 0.38 (0.02–34.8) | <0.001 | 0.08 (0.01–42) | 3 (0.12–100) | <0.001 |

| Parameters | Rho | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||

| • PMI vs. Albumin | 0.180 | 0.016 |

| • PMI vs. CRP | −0.160 | 0.032 |

| • PvMI vs. WBC | −0.156 | 0.037 |

| • PvMI vs. Hemoglobin | −0.270 | <0.001 |

| • PvMI vs. Creatinine | −0.257 | 0.001 |

| Female patients | ||

| • PMI vs. WBC | −0.307 | 0.002 |

| • PMI vs. NEU | −0.311 | 0.002 |

| • PMI vs. Albumin | 0.207 | 0.044 |

| • PMI vs. Triglyceride | −0.251 | 0.032 |

| • PvMI vs. ALT | −0.204 | 0.048 |

| • PvMI vs. GGT | −0.274 | 0.007 |

| • PvMI vs. Creatinine | −0.217 | 0.035 |

| Male patients | ||

| • PMI vs. Amylase | 0.258 | 0.018 |

| • PMI vs. Lipase | 0.284 | 0.009 |

| • PMI vs. Glucose | 0.233 | 0.042 |

| • PMI vs. CRP | −0.253 | 0.020 |

| • PvMI vs. Amylase | 0.268 | 0.014 |

| • PvMI vs. Lipase | 0.281 | 0.009 |

| • PvMI vs. ALP | 0.280 | 0.010 |

| ≥65 years (all patients) | ||

| • PvMI vs. Creatinine | −0.390 | 0.001 |

| • PvMI vs. ALT | −0.249 | 0.047 |

| ≥65 years (female patients) | ||

| • PvMI vs. Creatinine | −0.319 | 0.031 |

| • PvMI vs. GGT | −0.392 | 0.007 |

| • PvMI vs. AST | −0.316 | 0.032 |

| • PvMI vs. ALT | −0.335 | 0.023 |

| ≥65 years (male patients) | ||

| • PMI vs. Lipase | 0.490 | 0.039 |

| • PvMI vs. CCI | −0.479 | 0.044 |

| Outcome | Subgroup | Muscle Index | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complicated pancreatitis | Female patients | PMI 1 | 0.854 | 0.723–1.009 | 0.063 |

| PMI 2 | 0.655 | 0.462–0.929 | 0.018 | ||

| ≥65 years (male patients) | PvMI 3 | 0.669 | 0.411–1.088 | 0.105 | |

| ≥65 years (all patients) | PMI 4 | 0.829 | 0.682–1.007 | 0.059 | |

| PMI 5 | 0.775 | 0.604–0.995 | 0.045 | ||

| ICU requirement | ≥65 years (male patients) | PvMI 6 | 0.548 | 0.291–1.032 | 0.063 |

| ≥65 years (all patients) | PvMI 7 | 0.816 | 0.675–0.986 | 0.035 | |

| PvMI 8 | 0.780 | 0.611–0.997 | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Çelikdelen, S.Ö.; Keskin, Z.; Şahin, T.; Kollu, K.; Kizilarslanoglu, M.C. Potential Associations Between CT-Derived Muscle Indices and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis. Medicina 2026, 62, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010054

Çelikdelen SÖ, Keskin Z, Şahin T, Kollu K, Kizilarslanoglu MC. Potential Associations Between CT-Derived Muscle Indices and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇelikdelen, Selma Özlem, Zeynep Keskin, Tevhide Şahin, Korhan Kollu, and Muhammet Cemal Kizilarslanoglu. 2026. "Potential Associations Between CT-Derived Muscle Indices and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis" Medicina 62, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010054

APA StyleÇelikdelen, S. Ö., Keskin, Z., Şahin, T., Kollu, K., & Kizilarslanoglu, M. C. (2026). Potential Associations Between CT-Derived Muscle Indices and Clinical Outcomes in Acute Pancreatitis. Medicina, 62(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010054