Intralesional Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treating Chronic Peyronie’s Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Details

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. PRP Preparation and Injection Protocol

2.4. Outcomes and Patient Assessments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

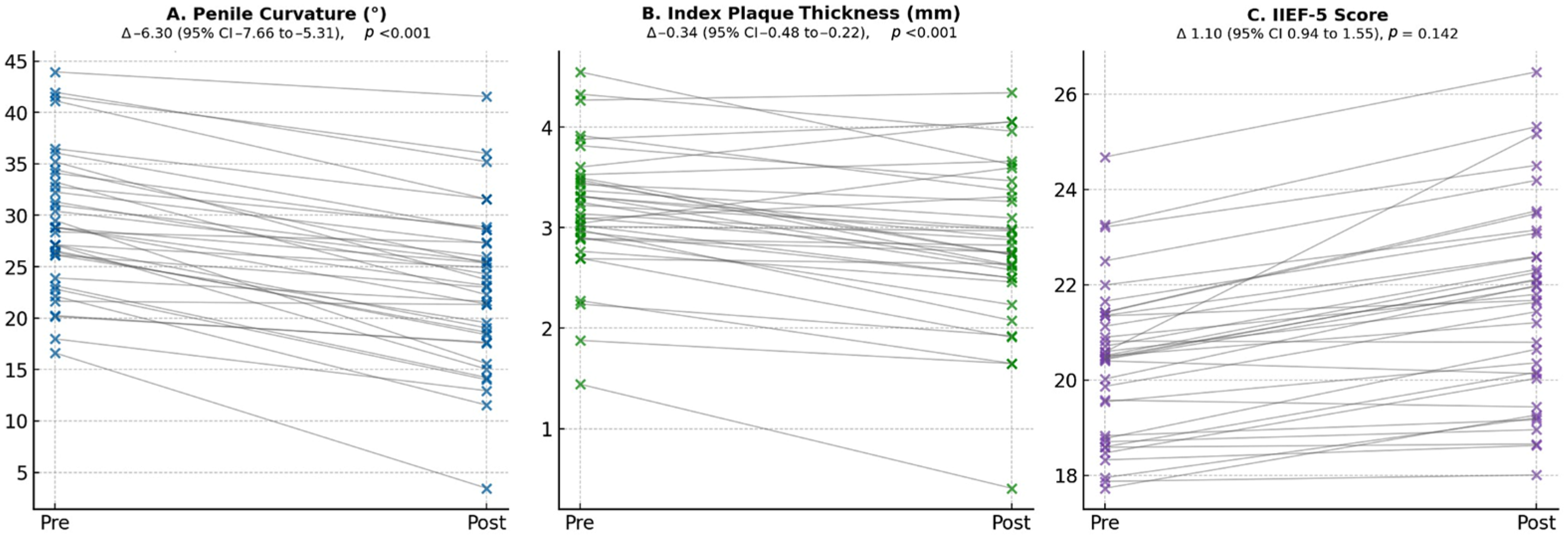

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings and Previous Literature

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CC BY | Creative Commons Attribution |

| CCH | Collagenase Clostridium histolyticum |

| CD | Clavien–Dindo classification |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CIs | Confidence Intervals |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| ED | Erectile Dysfunction |

| IIEF-5 | 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| Li-ESWT | Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy |

| MD | Medical Doctor |

| PD | Peyronie’s Disease |

| PDE5Is | Phosphodiesterase Type-5 Inhibitors |

| PDQ | Peyronie’s Disease Questionnaire |

| PNT | Penile Needling Therapy |

| PRP | Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| RBC | Red Blood Cell |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDΔ | Standard Deviation of the Paired Difference |

| SPL | Stretched Penile Length |

References

- Minore, A.; Cacciatore, L.; Presicce, F.; Iannuzzi, A.; Testa, A.; Raso, G.; Papalia, R.; Martini, M.; Scarpa, R.M.; Esperto, F. Intralesional and topical treatments for Peyronie’s disease: A narrative review of current knowledge. Asian J. Androl. 2025, 27, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmundo, M.G.; Durukan, E.; von Rohden, E.; Thy, S.A.; Jensen, C.F.S.; Fode, M. Platelet-rich plasma therapy in erectile dysfunction and Peyronie’s disease: A systematic review of the literature. World J. Urol. 2024, 42, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, F.C.; Barros, R.; Lima, T.F.N.; Velasquez, D.; Favorito, L.A.; Pozzi, E.; Dornbush, J.; Miller, D.; Petrella, F.; Ramasamy, R. Evidence of restorative therapies in the treatment of Peyronie disease: A narrative review. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2024, 50, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmann, A.; Boutin, E.; Faix, A.; Yiou, R. Tolerance and efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections in Peyronie’s disease: Pilot study. Prog. Urol. 2022, 32, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achraf, C.; Ammani, A.; El Anzaoui, J. Platelet-rich plasma in patients affected with Peyronie’s disease. Arab. J. Urol. 2023, 21, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dachille, G.; Panunzio, A.; Bizzotto, L.; D’Agostino, M.V.; Greco, F.; Guglielmi, G.; Carbonara, U.; Spilotros, M.; Citarella, C.; Ostuni, A.; et al. Platelet-rich plasma intra-plaque injections rapidly reduce penile curvature and improve sexual function in Peyronie’s disease patients: Results from a prospective large-cohort study. World J. Urol. 2025, 43, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergün, M.; Sağır, S. Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy and platelet-rich plasma: Effective combination treatment of chronic-phase Peyronie’s disease. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2025, 78, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Sexual and Reproductive Health 2025; Peyronie’s Disease Chapter; EAU Guidelines Office: Arnhem, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelâmi, A. Autophotography in evaluation of functional penile disorders. Urology 1983, 21, 628–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, R.C.; Cappelleri, J.C.; Smith, M.D.; Lipsky, J.; Peña, B.M. Development and evaluation of an abridged 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int. J. Impot. Res. 1999, 11, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindo, D.; Demartines, N.; Clavien, P.A. Classification of surgical complications: A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 2004, 240, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshuaibi, M.; Zugail, A.S.; Lombion, S.; Beley, S. New protocol in the treatment of Peyronie’s disease by combining platelet-rich plasma, percutaneous needle tunneling, and penile modeling: Preliminary results. Prog. Urol. 2024, 34, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, J.M. Analysis of paired data. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2025, 40, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Tumkaya, T.; Aryal, S.; Choi, H.; Claridge-Chang, A. Moving beyond P values: Data analysis with estimation graphics. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zugail, A.S.; Alshuaibi, M.; Lombion, S. Safety and feasibility of percutaneous needle tunneling with platelet-rich plasma injections for Peyronie’s disease in the outpatient setting: A pilot study. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2024, 36, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, B.R.; Velasquez, D.A.; Egemba, C. A phase 2 randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial to evaluate safety and efficacy of platelet-rich plasma injections for Peyronie’s disease: Clinical trial update. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2024, 36, 813–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virag, R. Evaluation of the benefit of using a combination of autologous platelet rich-plasma and hyaluronic acid for the treatment of Peyronie’s disease. Sex. Health Issues 2017, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Platelet-rich plasma: Evidence to support its use. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereaux, J.; Dargahi, N.; Fraser, S.; Nurgali, K.; Kiatos, D.; Apostolopoulos, V. Leucocyte-Rich Platelet-Rich Plasma Enhances Fibroblast and Extracellular Matrix Activity: Implications in Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellini, F.; Tani, A.; Vallone, L.; Nosi, D.; Pavan, P.; Bambi, F.; Orlandini, S.Z.; Sassoli, C. Platelet-Rich Plasma Prevents In Vitro Transforming Growth Factor-β1-Induced Fibroblast to Myofibroblast Transition: Involvement of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)-A/VEGF Receptor-1-Mediated Signaling. Cells 2018, 7, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnappa, P.; Tammaro, S.; Sneha, J.; Matippa, P.; Arcaniolo, D.; De Sio, M.; Manfredi, C. Virtual reality in the management of male sexual dysfunction: An updated narrative review of the literature. Sex. Med. Rev. 2025, 14, qeaf051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of patients | 36 |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 61.2 (10.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) Kg/m2 | 24.3 (2.5) |

| Smoking habits, n (%) | 15 (42) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 14 (38) |

| SPL, mean (SD), cm | 12.08 (1.86) |

| Duration of PD, mean (SD), months | 19.2 (5.8) |

| Penile curvature, mean (SD), degrees | 30.5 (7.26) |

| Direction of curvature, n (%) | |

| 15 (41.7) |

| 13 (36.1) |

| 8 (22.2) |

| Penile plaque, n (%) | |

| 28 (77.8) |

| 6 (16.7) |

| 2 (5.6) |

| Index penile plaque thickness, mean (SD), mm | 3.25 (0.69) |

| IIEF-5, mean (SD), points | 20.0 (1.72) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pucci, L.; Manfredi, C.; Sansone, C.; Tammaro, S.; Stanziola, G.; Langella, N.; Dachille, G.; Arcaniolo, D.; De Sio, M.; Carrino, M. Intralesional Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treating Chronic Peyronie’s Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina 2026, 62, 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010221

Pucci L, Manfredi C, Sansone C, Tammaro S, Stanziola G, Langella N, Dachille G, Arcaniolo D, De Sio M, Carrino M. Intralesional Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treating Chronic Peyronie’s Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010221

Chicago/Turabian StylePucci, Luigi, Celeste Manfredi, Catello Sansone, Simone Tammaro, Giorgio Stanziola, Nunzio Langella, Giuseppe Dachille, Davide Arcaniolo, Marco De Sio, and Maurizio Carrino. 2026. "Intralesional Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treating Chronic Peyronie’s Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study" Medicina 62, no. 1: 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010221

APA StylePucci, L., Manfredi, C., Sansone, C., Tammaro, S., Stanziola, G., Langella, N., Dachille, G., Arcaniolo, D., De Sio, M., & Carrino, M. (2026). Intralesional Platelet-Rich Plasma for Treating Chronic Peyronie’s Disease: A Single-Center Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicina, 62(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010221