Sex Hormone Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Abstract

1. Key Points

- Low testosterone levels seem to be associated with increased cardiovascular (CV) risk and mortality; however, the relationship remains complex. It is still debatable whether testosterone should be perceived as a biomarker of overall health or an independent cardiovascular risk factor.

- It seems that clinically tailored transdermal TRT is not associated with increased incidence of major cardiovascular events and mortality; moreover, it may even be protective when testosterone levels are normalized.

- While TRT showed promising results in metabolic syndrome treatment, due to inconsistent study results and possible conflicts of interest, further studies are needed.

- The impact of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) on cardiovascular diseases (CVD) in women remains inconclusive. Evidence suggests that initiating HRT within 10 years of menopause or before age 60 may lower CVD risk and mortality compared to later initiation.

- Transdermal HRT is considered safer than oral therapy—particularly in women with obesity or dyslipidemia—because it carries a lower risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and more favorable effects on lipid metabolism.

2. Introduction

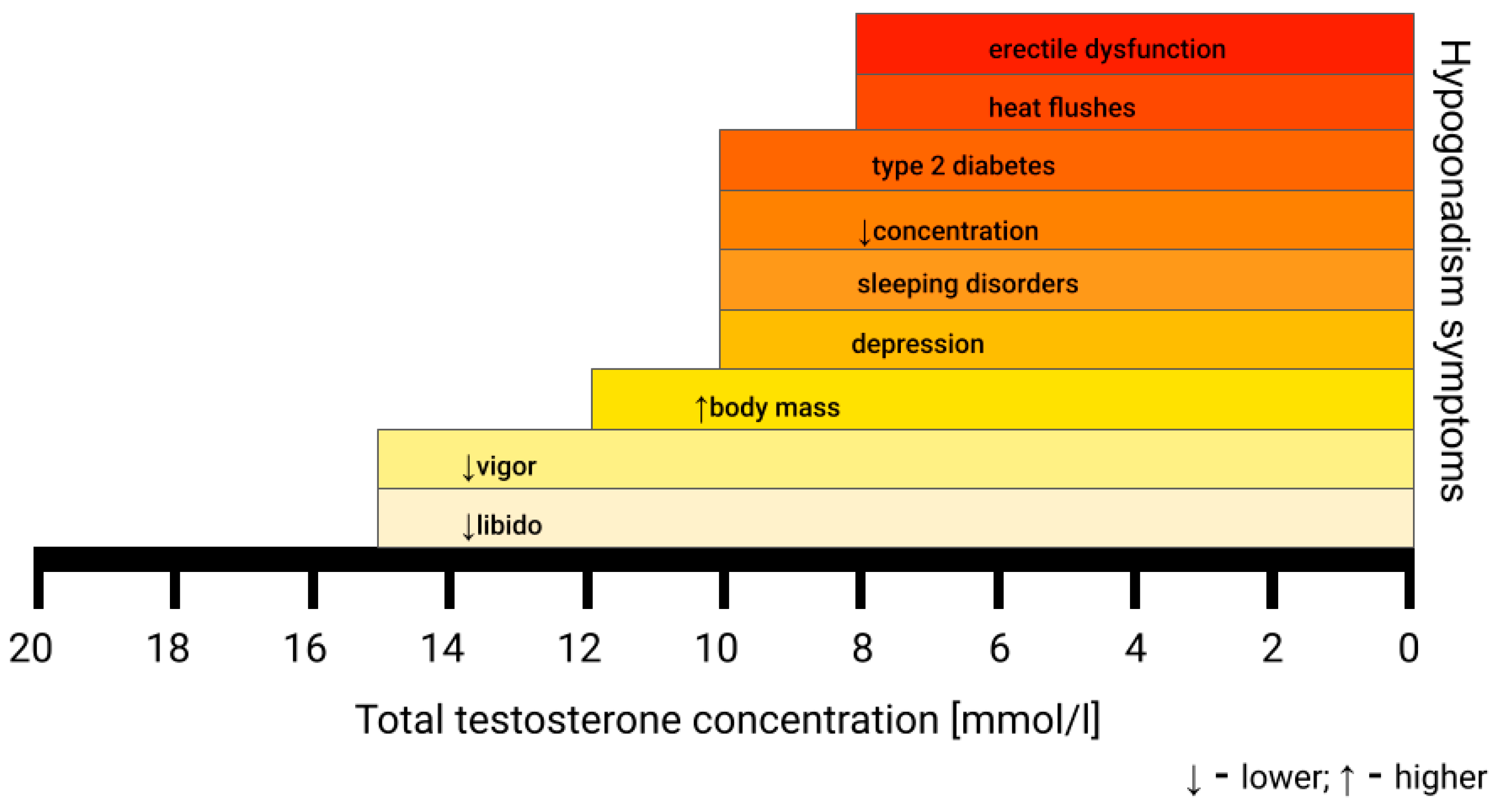

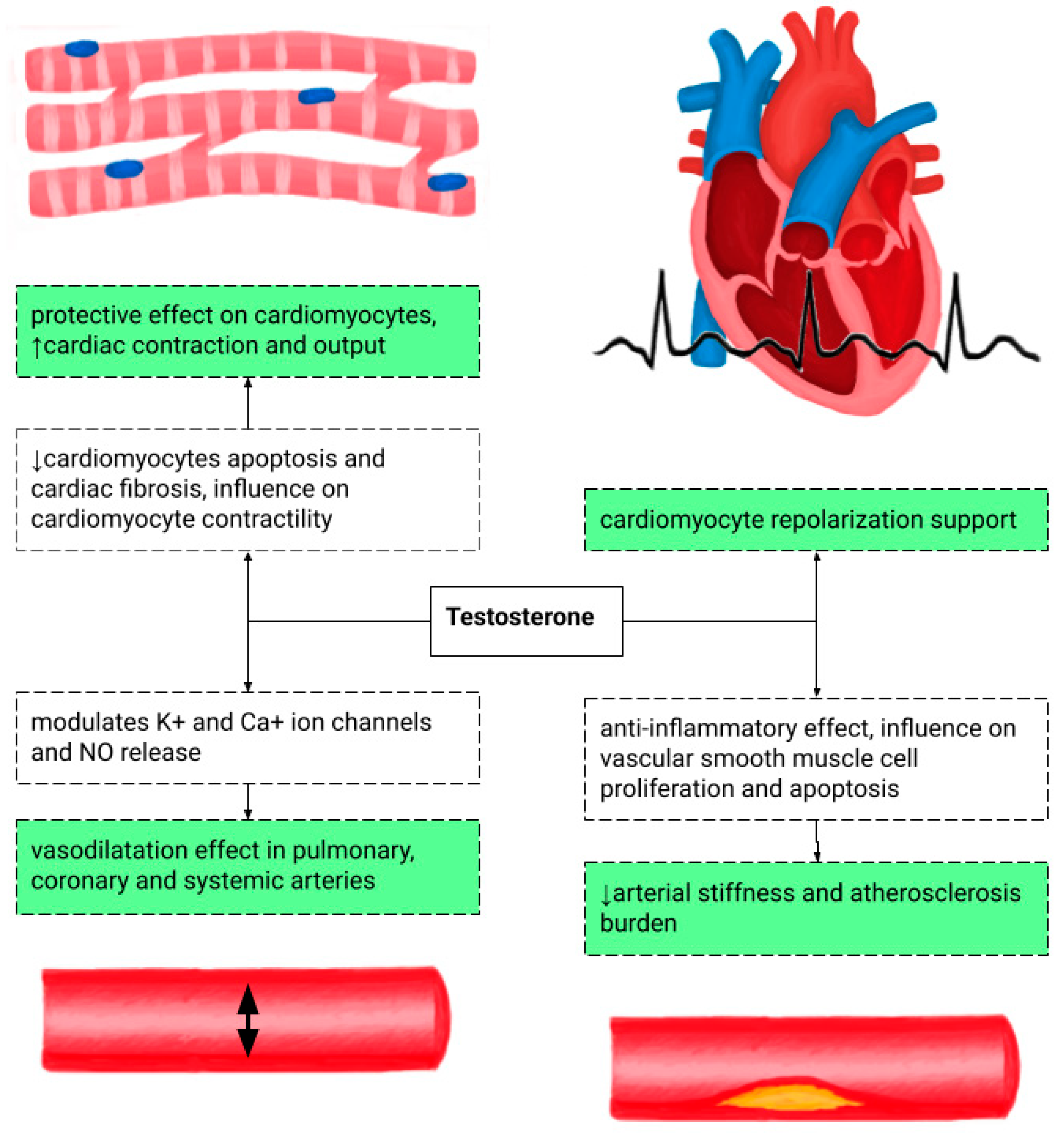

3. Hypogonadism

4. Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Cardiovascular Risk

5. Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Mortality

6. Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Metabolic Disorders

7. Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Heart Failure

8. Anabolic Steroids and Cardiomyopathy

9. Hormonal Replacement Therapy in Women and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

10. Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy in Transgender Women and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

11. Contraception and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

11.1. Combined Oral Contraception and Cardiovascular Risk

11.2. Progestogens and Cardiovascular Risk

11.3. Hormonal Contraception Summary and Cardiovascular Risk Considerations

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| HRT | hormone replacement therapy |

| TRT | testosterone replacement therapy |

| CV | cardiovascular |

| HF | heart failure |

| VTE | venous thromboembolism |

| LOH | late-onset hypogonadism |

| HpEF | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| EAU | European Association of Urology |

| SHBG | sex hormone-binding globulin |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| TT | total testosterone concentration |

| fT | free testosterone |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| MACE | major adverse cardiovascular event |

| TOM | The Testosterone in Older Men with Mobility Limitations |

| DHEA | dehydroepiandrosterone |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| TG | triglyceride |

| HbA1c | hemoglobin A1c |

| FPG | fasting plasma glucose |

| BP | blood pressure |

| 6MWT | 6-minute walk test |

| peak VO2 | peak oxygen consumption |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| AAS | anabolic androgenic steroid |

| LV | left ventricle |

| RAAS | renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| EF | ejection fraction |

| RV | right ventricle |

| CCTA | coronary computed tomography angiography |

| FSH | follicle-stimulating hormone |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| DM | diabetes |

| WHI | Woman’s Health Initiative |

| USA | the United States |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| ELITE | Early Versus Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol |

| CIMT | carotid artery intima-media thickness |

| ASCVD | atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| TIA | transient ischemic attack |

| PE | pulmonary embolism |

| GAHT | gender-affirming hormone therapy |

| OR | odds ratio |

| SMR | standardized mortality ratio |

| COC | combined oral contraception |

| RR | relative risk |

| T2DM | type 2 diabetes |

| T1DM | type 1 diabetes |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| POC | progestogen-only contraception |

| LG-IUDs | intrauterine levonorgestrel devices |

| IUDs | intrauterine devices |

| U.S. MEC | U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use |

| ACOG | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

References

- Corona, G.; Rastrelli, G.; Monami, M.; Guay, A.; Buvat, J.; Sforza, A.; Forti, G.; Mannucci, E.; Maggi, M. Hypogonadism as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in men: A meta-analytic study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 165, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakaran, A.; Ar, S.; Rajagambeeram, R.; Nanda, S.K.; Daniel, M. SHBG and Insulin resistance—Nexus revisited. Bioinformation 2024, 20, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsametis, C.P.; Isidori, A.M. Testosterone replacement therapy: For whom, when and how? Metabolism 2018, 86, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunenfeld, B.; Mskhalaya, G.; Zitzmann, M.; Arver, S.; Kalinchenko, S.; Tishova, Y.; Morgentaler, A. Recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of hypogonadism in men. Aging Male 2015, 18, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, C.J.; Lo, K.; Lee, Y.; Krakowsky, Y.; Garbens, A.; Satkunasivam, R.; Herschorn, S.; Kodama, R.T.; Cheung, P.; Narod, S.A.; et al. Survival and cardiovascular events in men treated with testosterone replacement therapy: An intention-to-treat observational cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shores, M.M.; Smith, N.L.; Forsberg, C.W.; Anawalt, B.D.; Matsumoto, A.M. Testosterone treatment and mortality in men with low testosterone levels. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, 2050–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Goulis, D.G.; Huhtaniemi, I.; Zitzmann, M.; Toppari, J.; Forti, G.; Vanderschueren, D.; Wu, F.C. European Academy of Andrology (EAA) guidelines on investigation, treatment and monitoring of functional hypogonadism in males: Endorsing organization: European Society of Endocrinology. Andrology 2020, 8, 970–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, K.; Blackwell, M.; Blackwell, T. Testosterone Replacement Therapy and Cardiovascular Disease: Balancing Safety and Risks in Hypogonadal Men. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakis, N.; Kreouzi, M.; Hitas, C.; Anagnostou, D.; Kollia, Z.; Vamvakou, G.; Nikolaou, M. Testosterone replacement therapy in heart failure: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hormones 2025, 24, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbonetti, A.; D’Andrea, S.; Francavilla, S. Testosterone replacement therapy. Andrology 2020, 8, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesti, F.; Pofi, R.; Minnetti, M.; Tenuta, M.; Gianfrilli, D.; Isidori, A.M. Late-onset hypogonadism: Reductio ad absurdum of the cardiovascular risk-benefit of testosterone replacement therapy. Andrology 2020, 8, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lodovico, E.; Facondo, P.; Delbarba, A.; Pezzaioli, L.C.; Maffezzoni, F.; Cappelli, C.; Ferlin, A. Testosterone, Hypogonadism, and Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2022, 15, e008755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal de Velasco, L.M.; González Flores, J.E. Testosterone Therapy in Men in Their 40s: A Narrative Review of Indications, Outcomes, and Mid-Term Safety. Cureus 2025, 17, e92778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Oni, O.A.; Gupta, K.; Chen, G.; Sharma, M.; Dawn, B.; Sharma, R.; Parashara, D.; Savin, V.J.; Ambrose, J.A. Normalization of testosterone level is associated with reduced incidence of myocardial infarction and mortality in men. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2706–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Oni, O.A.; Chen, G.; Sharma, M.; Dawn, B.; Sharma, R.; Parashara, D.; Savin, V.J.; Barua, R.S.; Gupta, K. Association Between Testosterone Replacement Therapy and the Incidence of DVT and Pulmonary Embolism: A Retrospective Cohort Study of the Veterans Administration Database. Chest 2016, 150, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Bhasin, S.; Flevaris, P.; Mitchell, L.M.; Basaria, S.; Boden, W.E.; Cunningham, G.R.; Granger, C.B.; Khera, M.; Thompson, I.M., Jr.; et al. Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillargeon, J.; Urban, R.J.; Kuo, Y.F.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Raji, M.A.; Du, F.; Lin, Y.L.; Goodwin, J.S. Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Older Men Receiving Testosterone Therapy. Ann. Pharmacother. 2014, 48, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basaria, S.; Coviello, A.D.; Travison, T.G.; Storer, T.W.; Farwell, W.R.; Jette, A.M.; Eder, R.; Tennstedt, S.; Ulloor, J.; Zhang, A.; et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Freeman, G.; Cowling, B.J.; Schooling, C.M. Testosterone therapy and cardiovascular events among men: A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Rastrelli, G.; Di Pasquale, G.; Sforza, A.; Mannucci, E.; Maggi, M. Endogenous Testosterone Levels and Cardiovascular Risk: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. J. Sex Med. 2018, 15, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, B.; Vuilleumier, N.; Nanchen, D.; Collet, T.H.; Klingenberg, R.; Räber, L.; Auer, R.; Carballo, D.; Carballo, S.; Aghlmandi, S.; et al. Prognostic value of total testosterone levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, M.; McAlister, F.A.; Coglianese, E.E.; Vidi, V.; Vasaiwala, S.; Bakal, J.A.; Armstrong, P.W.; Ezekowitz, J.A. Testosterone supplementation in heart failure: A meta-analysis. Circ. Heart Fail. 2012, 5, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarz, N.; Miedziaszczyk, M.; Wieckowska, B.; Szalek, E.; Lacka, K. Effects of Testosterone Replacement Therapy on Metabolic Syndrome in Male Patients-Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shigehara, K.; Konaka, H.; Nohara, T.; Izumi, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kadono, Y.; Iwamoto, T.; Koh, E.; Mizokami, A.; Namiki, M. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy on metabolic syndrome among Japanese hypogonadal men: A subanalysis of a prospective randomised controlled trial (EARTH study). Andrologia 2018, 50, e12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustsen, I.R.; Larsen, S.B.; Duun-Henriksen, A.K.; Tjønneland, A.; Kjær, S.K.; Brasso, K.; Johansen, C.; Dalton, S.O. Risk of cardiovascular events in men treated for prostate cancer compared with prostate cancer-free men. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, X.; Bai, W. Testosterone Supplementation in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Windfeld-Mathiasen, J.; Heerfordt, I.M.; Dalhoff, K.P.; Andersen, J.T.; Andersen, M.A.; Johansson, K.S.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; Olsen, F.J.; Horwitz, H. Cardiovascular Disease in Anabolic Androgenic Steroid Users. Circulation 2025, 151, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadah, K.; Gopi, G.; Lingireddy, A.; Blumer, V.; Dewald, T.; Mentz, R.J. Anabolic androgenic steroids and cardiomyopathy: An update. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1214374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhusban, Z.; Alaaraj, M.M.; Saimeh, A.R.; Nassar, W.; Awad, A.; Ghanima, K.; Abouelkheir, M.; Hamed, A.M.; Afsa, A.; Morra, M.E. Steroid-Induced Cardiomyopathy: Insights from a Systematic Literature Review and a Case Report. Clin. Case Rep. 2025, 13, e70171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montisci, M.; El Mazloum, R.; Cecchetto, G.; Terranova, C.; Ferrara, S.D.; Thiene, G.; Basso, C. Anabolic androgenic steroids abuse and cardiac death in athletes: Morphological and toxicological findings in four fatal cases. Forensic. Sci. Int. 2012, 217, e13–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, M.C.; Lawrence, C. Anabolic steroid abuse and cardiac death. Med. J. Aust. 1993, 158, 346–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielb, J.; Saffak, S.; Weber, J.; Baensch, L.; Shahjerdi, K.; Celik, A.; Farahat, N.; Riek, S.; Chavez-Talavera, O.; Grandoch, M.; et al. Transformation or replacement—Effects of hormone therapy on cardiovascular risk. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 254, 108592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Safi, Z.A.; Santoro, N. Menopausal hormone therapy and menopausal symptoms. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassertheil-Smoller, S.; Hendrix, S.L.; Limacher, M.; Heiss, G.; Kooperberg, C.; Baird, A.; Kotchen, T.; Curb, J.D.; Black, H.; Rossouw, J.E.; et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on stroke in postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative: A randomized trial. JAMA 2003, 289, 2673–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manson, J.E.; Hsia, J.; Johnson, K.C.; Rossouw, J.E.; Assaf, A.R.; Lasser, N.L.; Trevisan, M.; Black, H.R.; Heckbert, S.R.; Detrano, R.; et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G.L.; Limacher, M.; Assaf, A.R.; Bassford, T.; Beresford, S.A.; Black, H.; Bonds, D.; Brunner, R.; Brzyski, R.; Caan, B.; et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004, 291, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, X. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obs. Gynecol. 2018, 131, 604. [CrossRef]

- Stuenkel, C.A.; Davis, S.R.; Gompel, A.; Lumsden, M.A.; Murad, M.H.; Pinkerton, J.V.; Santen, R.J. Treatment of Symptoms of the Menopause: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 3975–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, J.E.; Prentice, R.L.; Manson, J.E.; Wu, L.; Barad, D.; Barnabei, V.M.; Ko, M.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Margolis, K.L.; Stefanick, M.L. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA 2007, 297, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boardman, H.M.; Hartley, L.; Eisinga, A.; Main, C.; Roqué i Figuls, M.; Bonfill Cosp, X.; Gabriel Sanchez, R.; Knight, B. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 10, CD002229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, M.A.; Irigoyen, M.C.; Spritzer, P.M. Menopause, estrogens, and endothelial dysfunction: Current concepts. Clinics 2007, 62, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodis, H.N.; Mack, W.J.; Henderson, V.W.; Shoupe, D.; Budoff, M.J.; Hwang-Levine, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, M.; Dustin, L.; Kono, N.; et al. Vascular Effects of Early versus Late Postmenopausal Treatment with Estradiol. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergendal, A.; Kieler, H.; Sundström, A.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Kocoska-Maras, L. Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with local and systemic use of hormone therapy in peri- and postmenopausal women and in relation to type and route of administration. Menopause 2016, 23, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldštajn, M.Š.; Mikuš, M.; Ferrari, F.A.; Bosco, M.; Uccella, S.; Noventa, M.; Török, P.; Terzic, S.; Laganà, A.S.; Garzon, S. Effects of transdermal versus oral hormone replacement therapy in postmenopause: A systematic review. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 1727–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straczek, C.; Oger, E.; Yon de Jonage-Canonico, M.B.; Plu-Bureau, G.; Conard, J.; Meyer, G.; Alhenc-Gelas, M.; Lévesque, H.; Trillot, N.; Barrellier, M.T.; et al. Prothrombotic mutations, hormone therapy, and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women: Impact of the route of estrogen administration. Circulation 2005, 112, 3495–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakatsuki, A.; Okatani, Y.; Ikenoue, N.; Fukaya, T. Different effects of oral conjugated equine estrogen and transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on size and oxidative susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein particles in postmenopausal women. Circulation 2002, 106, 1771–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitcroft, S.I.; Crook, D.; Marsh, M.S.; Ellerington, M.C.; Whitehead, M.I.; Stevenson, J.C. Long-term effects of oral and transdermal hormone replacement therapies on serum lipid and lipoprotein concentrations. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 84, 222–226. [Google Scholar]

- Cushman, M.; Kuller, L.H.; Prentice, R.; Rodabough, R.J.; Psaty, B.M.; Stafford, R.S.; Sidney, S.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Estrogen plus progestin and risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2004, 292, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimbo, D.; Wang, L.; Lamonte, M.J.; Allison, M.; Wellenius, G.A.; Bavry, A.A.; Martin, L.W.; Aragaki, A.; Newman, J.D.; Swica, Y.; et al. The effect of hormone therapy on mean blood pressure and visit-to-visit blood pressure variability in postmenopausal women: Results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trials. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slopien, R.; Wender-Ozegowska, E.; Rogowicz-Frontczak, A.; Meczekalski, B.; Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz, D.; Jaremek, J.D.; Cano, A.; Chedraui, P.; Goulis, D.G.; Lopes, P.; et al. Menopause and diabetes: EMAS clinical guide. Maturitas 2018, 117, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Fournier, A.; Fabre, A.; Simon, N.; Mesrine, S.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Balkau, B.; Clavel-Chapelon, F. Menopausal hormone therapy and new-onset diabetes in the French Etude Epidemiologique de Femmes de la Mutuelle Générale de l’Education Nationale (E3N) cohort. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2092–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, J.; Bouman, W.P.; Van Den Noortgate, W.; Claes, L.; Witcomb, G.; Fernandez-Aranda, F. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies in transsexualism. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangpricha, V.; den Heijer, M. Oestrogen and anti-androgen therapy for transgender women. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, E.; Lee, J.; Torbati, T.; Garcia, M.; Merz, C.N.B.; Shufelt, C. Cardiovascular implications of gender-affirming hormone treatment in the transgender population. Maturitas 2019, 129, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, T.; Nguyen, T.; Ryan, A.; Dwairy, A.; McCaffrey, J.; Yunus, R.; Forgione, J.; Krepp, J.; Nagy, C.; Mazhari, R.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual Outcomes 2019, 12, e005597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asscheman, H.; Giltay, E.J.; Megens, J.A.; de Ronde, W.P.; van Trotsenburg, M.A.; Gooren, L.J. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 164, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulprachakarn, K.; Ounjaijean, S.; Rerkasem, K.; Molinsky, R.L.; Demmer, R.T. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among transgender women in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 10, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Guallar, E.; Ouyang, P.; Subramanya, V.; Vaidya, D.; Ndumele, C.E.; Lima, J.A.; Allison, M.A.; Shah, S.J.; Bertoni, A.G.; et al. Endogenous Sex Hormones and Incident Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Women. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2555–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, S.K.; Rabinovich-Nikitin, I.; Kirshenbaum, L.A. Oral hormonal contraceptives and cardiovascular risks in females. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2024, 102, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skafar, D.F.; Xu, R.; Morales, J.; Ram, J.; Sowers, J.R. Clinical review 91: Female sex hormones and cardiovascular disease in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997, 82, 3913–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Pang, Y. Protective actions of progesterone in the cardiovascular system: Potential role of membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs) in mediating rapid effects. Steroids 2013, 78, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K.; Abma, J.C. Current Contraceptive Status Among Females Ages 15–49: United States, 2022–2023. NCHS Data Brief 2025, 539, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, S.; Petitti, D.B.; Soff, G.A.; Cundiff, D.L.; Tolan, K.K.; Quesenberry, C.P., Jr. Venous thromboembolic disease in users of low-estrogen combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives. Contraception 2004, 70, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidegaard, Ø.; Løkkegaard, E.; Svendsen, A.L.; Agger, C. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: National follow-up study. BMJ 2009, 339, b2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oedingen, C.; Scholz, S.; Razum, O. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of combined oral contraceptives on the risk of venous thromboembolism: The role of the progestogen type and estrogen dose. Thromb. Res. 2018, 165, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, N.A.; Blyler, C.A.; Bello, N.A. Oral Contraceptive Pills and Hypertension: A Review of Current Evidence and Recommendations. Hypertension 2023, 80, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K. Associations between oral contraceptive use and risks of hypertension and prehypertension in a cross-sectional study of Korean women. BMC Womens Health 2013, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, R.J. Effect on blood pressure or changing from high to low dose steroid preparations in women with oral contraceptive induced hypertension. Scott. Med. J. 1982, 27, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, R.E.; Helmerhorst, F.M.; Lijfering, W.M.; Stijnen, T.; Algra, A.; Dekkers, O.M. Combined oral contraceptives: The risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD011054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, L.; Hennekens, C.H.; Rosner, B.; Belanger, C.; Rothman, K.J.; Speizer, F.E. Oral contraceptive use in relation to nonfatal myocardial infarction. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1980, 111, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampfer, M.J.; Willett, W.C.; Colditz, G.A.; Speizer, F.E.; Hennekens, C.H. A prospective study of past use of oral contraceptive agents and risk of cardiovascular diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Huang, J.; Xu, B.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, X.; et al. Associations of Oral Contraceptive Use with Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Death: Evidence from the UK Biobank Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Liu, Q.; Bi, J.; Qin, X.; Fang, Q.; Luo, F.; Huang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, L. Reproductive factors, genetic susceptibility and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab. 2024, 50, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snell-Bergeon, J.K.; Dabelea, D.; Ogden, L.G.; Hokanson, J.E.; Kinney, G.L.; Ehrlich, J.; Rewers, M. Reproductive history and hormonal birth control use are associated with coronary calcium progression in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 2142–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, A.; Kiechl, S.J.; Gande, N.; Hochmayr, C.; Bernar, B.; Stock, K.; Geiger, R.; Egger, A.; Griesmacher, A.; Knoflach, M.; et al. Influence of Oral Contraceptives on Lipid Profile and Trajectories in Healthy Adolescents-Data From the EVA-Tyrol Study. J. Adolesc. Health. 2024, 75, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teichmann, A. Metabolic profile of six oral contraceptives containing norgestimate, gestodene, and desogestrel. Int. J. Fertil. Menopausal Stud. 1995, 40, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skouby, S.O.; Endrikat, J.; Düsterberg, B.; Schmidt, W.; Gerlinger, C.; Wessel, J.; Goldstein, H.; Jespersen, J. A 1-year randomized study to evaluate the effects of a dose reduction in oral contraceptives on lipids and carbohydrate metabolism: 20 microg ethinyl estradiol combined with 100 microg levonorgestrel. Contraception 2005, 71, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarajan, K.; Rich, M.W. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Prognosis of Heart Failure in Older Adults. Heart Fail. Clin. 2017, 13, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Li, H.; Chen, P.; Xie, N.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, C. Association between oral contraceptive use and incident heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 2282–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachenfeld, N.S.; Keefe, D.L. Estrogen effects on osmotic regulation of AVP and fluid balance. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 283, E711–E721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, N.K.; Nguyen, A.T.; Whiteman, M.K.; Curtis, K.M. Progestin-only contraception and thrombosis: An updated systematic review. Contraception 2025, 110978, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, K.; Amaral, E.; Hays, M.; Viscola, M.A.; Mehta, N.; Bahamondes, L. Pharmacokinetic interactions between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate and combination antiretroviral therapy. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrum, R.H.; Soo, J.; Ham, S.A.; Cohen, K.S.; Snow, S.G. Association of Progestogens and Venous Thromboembolism Among Women of Reproductive Age. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 140, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glisic, M.; Shahzad, S.; Tsoli, S.; Chadni, M.; Asllanaj, E.; Rojas, L.Z.; Brown, E.; Chowdhury, R.; Muka, T.; Franco, O.H. Association between progestin-only contraceptive use and cardiometabolic outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonis, H.; Løkkegaard, E.; Kragholm, K.; Granger, C.B.; Møller, A.L.; Mørch, L.S.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Meaidi, A. Stroke and myocardial infarction with contemporary hormonal contraception: Real-world, nationwide, prospective cohort study. BMJ 2025, 388, e082801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnar, G.; Andersen, K.K.; Olsen, T.S. Risk of Stroke in Women Using Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Device for Contraception. Stroke 2024, 55, 1830–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease; Contraception, S.H. Cardiovascular disease and use of oral and injectable progestogen-only contraceptives and combined injectable contraceptives. Results of an international, multicenter, case-control study. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Contraception 1998, 57, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.F. Progestogen-only pills and high blood pressure: Is there an association? A literature review. Contraception 2004, 69, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, T.; Burke, A.E.; Barnhart, K.T.; Archer, D.F.; Colli, E.; Westhoff, C.L. A 1-year prospective, open-label, single-arm, multicenter, phase 3 trial of the contraceptive efficacy and safety of the oral progestin-only pill drospirenone 4 mg using a 24/4-day regimen. Contracept X 2020, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelkers, W.; Foidart, J.M.; Dombrovicz, N.; Welter, A.; Heithecker, R. Effects of a new oral contraceptive containing an antimineralocorticoid progestogen, drospirenone, on the renin-aldosterone system, body weight, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and lipid metabolism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995, 80, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkfeldt, J.; Virkkunen, A.; Dieben, T. The effects of two progestogen-only pills containing either desogestrel (75 microg/day) or levonorgestrel (30 microg/day) on lipid metabolism. Contraception 2001, 64, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Würtz, P.; Auro, K.; Morin-Papunen, L.; Kangas, A.J.; Soininen, P.; Tiainen, M.; Tynkkynen, T.; Joensuu, A.; Havulinna, A.S. Effects of hormonal contraception on systemic metabolism: Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunca, A.F.; Ilıman, D.E.; Karakaş, S.; Alay, I.; Eren, E.; Yildiz, S.; Kaya, C. Effects of Dienogest Only Treatment on Lipid Profile. Med. J. Bakirkoy 2022, 18, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, K.J.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Davis, M.B.; Madden, T.; Park, K.; Bello, N.A.; American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Disease in Women Committee and the Cardio-Obstetrics Work Group. Contraception and Reproductive Planning for Women with Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Focus Seminar 5/5. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Curtis, K.M.; Tepper, N.K.; Kortsmit, K.; Brittain, A.W.; Snyder, E.M.; Cohen, M.A.; Zapata, L.B.; Whiteman, M.K. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2024. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2024, 73, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.M.; Tepper, N.K.; Jatlaoui, T.C.; Berry-Bibee, E.; Horton, L.G.; Zapata, L.B.; Simmons, K.B.; Pagano, H.P.; Jamieson, D.J.; Whiteman, M.K. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2016, 65, 1–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Gynecologic Considerations for Adolescents and Young Women with Cardiac Conditions: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 813. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, e90–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S.; MacGregor, A.; Nelson-Piercy, C. Risks of contraception and pregnancy in heart disease. Heart 2006, 92, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, A.; Vyas, A.; Roselle, A.; Velu, D.; Hota, L.; Kadiyala, M. Contraception and Cardiovascular Effects: What Should the Cardiologist Know? Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2023, 25, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, P.M.; Spillers, N.J.; Talbot, N.C.; Sinnathamby, E.S.; Ellison, D.; Kelkar, R.A.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Kaye, A.D. Testosterone replacement therapy: Clinical considerations. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, A.; Fantus, R.J. Testosterone Replacement Therapy for Testosterone Deficiency in Older Men. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2025, 41, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | Indication |

|---|---|

| 40–49 | TRT is recommended when TT < 300 ng/dL (10.4 nmol/L) with co-existing hypogonadal symptoms |

| 50–80 | when TT < 15 nmol/L with hypogonadal symptoms—TRT may be beneficial (fT < 225 pmol/L (65 pg/mL) or 243 pmol/L (70 pg/mL) support TRT administration) |

| when TT < 12.1 nmol/L—indication to start TRT |

| Study | Study Design | Endpoint | Result | Limitations | Guideline Inconsistencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lincoff et al., 2023 [16] Cardiovascular Safety of Testosterone-Replacement Therapy | A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, noninferiority trial; 5246 men randomly assigned transdermal 1.62% testosterone gel or placebo gel | Occurrence of any component of a composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke | TRT was noninferior to the placebo with respect to the incidence of MACCE | High rate of treatment discontinuations; short treatment and follow-up time | Heightened risk of MI/stroke during TRT |

| Wallis et al., 2016 [5] Survival and cardiovascular events in men treated with testosterone replacement therapy: an intention-to-treat observational cohort study | A population-based matched cohort study; 10,311 men treated with TRT and 28,029 controls | Mortality, CV events, and prostate cancer | Long-term TRT—reduced mortality, cardiovascular events, and prostate cancer; short-term TRT—higher mortality and cardiovascular events | Lack of randomization; possible selection and detection bias; no baseline T level | Intensive cardiac monitoring during the first 3–4 months of TRT was not suggested; TRT requires frequent prostate cancer screening |

| Baillargeon et al., 2014 [17] Risk of Myocardial Infarction in Older Men Receiving Testosterone Therapy | A population-based cohort; 6355 patients on TRT and 19,065 testosterone nonusers | MI | TRT was not associated with a heightened risk of MI; TRT seemed to be protective against MI in men from the highest-risk group | No assessment of actual T level; only intramuscular route of T administration | TRT should be avoided or used with extreme caution in men with high CV risk |

| Basaria et al., 2010 [18] Adverse events associated with testosterone administration | A randomized, controlled trial; 209 participants randomly assigned to receive placebo gel or testosterone gel | Primary endpoint—mobility improvement measured by leg-press strength; safety endpoints: MI, stroke, CV mortality, hospitalization for HF, UA, arrhythmias, and HT-related events | The application of a testosterone gel was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events; TRT improved leg and chest-press strength | Study conducted on an extremely high-risk population; terminated early; may lack statistical power | Contemporary guidelines suggested TRT was safe if patients were screened for prostate cancer |

| Xu et al., 2013 [19] Testosterone therapy and cardiovascular events among men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials | A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials of TRT lasting 12+ weeks; encompassed 2994 men | CV events: MI, stoke, CV mortality, PCI, CABG, investigator-reported palpitations, peripheral edema, other HF symptoms, and new-onset arrhythmias | TRT increased the risk of cardiovascular-related events regardless of the baseline T level; the effect of TRT varied regarding the source of funding—in trials funded by the pharmaceutical industry, the CV risk was lower | Pooled small trials were inconsistent; broad endpoint, including minor events | Guidelines relying on pharmaceutical data might be incomplete in terms of safety |

| Corona et al., 2011 [1] Hypogonadism as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality in men: a meta-analytic study | A meta-analysis of 6 RCT, 54 cross-sectional, and 10 longitudinal studies to evaluate the relationship between hypogonadism and CV mortality | Cross-sectional endpoint—prevalence of CV disease; longitudinal endpoint—all-cause mortality and CV mortality; RCT endpoint—changes in treadmill test parameters | Lower testosterone and higher 7-β estradiol levels were associated with increased risk of CVD and CV mortality | Included a small number of RCTs with 258 patients, and the follow-up was short (23 to 52 weeks); in the longitudinal and cross-sectional studies, there was an inability to determine if low T was the biomarker or the cause | It was a novelty for contemporary guidelines that a low T level is one of the CVD risk factors, as well as a high estrogen level |

| Corona et al., 2018 [20] Endogenous Testosterone Levels and Cardiovascular Risk: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies | A meta-analysis of 37 observational studies, including 43,041 men | CV mortality and morbidity | Low T in aging men could represent a marker of CV risk | Many incorporated studies lacked complete follow-up and suffered from poor management of missing data; the link between low T and CV death was influenced by diabetes and active smoking | Guidelines recommend a strict T level threshold—in the study, men in the “low-normal” range still showed increased CV risk (linear association) |

| Shores et al., 2012 [6] Testosterone treatment and mortality in men with low testosterone levels | An observational study, encompassing 1 031 male veterans, testosterone-treated, compared with untreated men | All-cause mortality | In men with low T levels, testosterone TRT was associated with decreased mortality compared with no the TRT group | Lack of randomization; non-standardized testosterone level measurement; possible “Healthy User” selection bias | Contemporary guidelines focused on the potential risks of TRT, while according to this study, the real danger was not treating the patient with a very low T level |

| Gencer et al., 2021 [21] Prognostic value of total testosterone levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes | A prospective observational cohort study, including 1054 men hospitalized for ACS | All-cause mortality at one year | After adjustment for high-risk confounders, low T levels were not associated with mortality; a low T level was prevalent in almost 40% | T levels measured during acute cardiac event; one year follow-up; no interventional data | A low T level may serve as a mortality predictor, which is not included in guidelines; guidelines recommend testing T levels in stable and healthy patients |

| Sharma et al., 2016 [15] Association Between Testosterone Replacement Therapy and the Incidence of DVT and Pulmonary Embolism: A Retrospective Cohort Study of the Veterans Administration Database. | A retrospective study; 10,854 subjects without TRT and 60,553 with TRT (after treatment, 38,362 normal T, 22,191 low TT) | The incidence of DVT and PE during TRT therapy | TRT in patients with low–moderate risk of DVT/PE was not associated with an increased risk of DVT/PE | Recent surgery and immobilization not taken into consideration; excluded patients with prior DVT/PE/hypercoagulable state | Guidelines treat the history of VTE as a relative contraindication for TRT |

| Study | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wassertheil-Smoller et al., 2003 [34] | Randomized controlled trial (WHI) | Postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years; conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg/day + medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) 2.5 mg/day | Combined HRT associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke; no protective effect on cerebrovascular outcomes |

| Manson et al., 2003 [35] | Randomized controlled trial (WHI) | Women aged 50–79 years without prior CHD; CEE 0.625 mg/day + MPA 2.5 mg/day | No reduction in coronary heart disease risk; early increase in CHD events observed after initiation of therapy |

| Anderson et al., 2004 [36] | Randomized controlled trial (WHI) | Postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years with hysterectomy; CEE 0.625 mg/day | Estrogen-only therapy did not reduce coronary heart disease risk; increased risk of stroke observed |

| Yang et al., 2013 [37] | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials | Postmenopausal women receiving mainly standard doses (CEE 0.625 mg/day ± MPA 2.5 mg/day) | HRT did not reduce cardiovascular mortality or coronary events; increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism reported |

| Rossouw et al., 2007 [40] | Secondary analysis of randomized controlled trials (WHI) | Women aged 50–79 years; stratified by <10, 10–19, ≥20 years since menopause | CVD risk varied by age and years since menopause; younger women and those closer to menopause showed lower absolute CVD risk, but no overall cardiovascular benefit; increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism |

| Boardman et al., 2015 [41] | Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis | Postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy (oral and transdermal) for primary or secondary CVD prevention | Hormone therapy did not prevent cardiovascular disease; increased risk of stroke and venous thromboembolism; evidence does not support HRT for CVD prevention |

| Hodis et al., 2016 [43] | Randomized controlled trial (ELITE) | Healthy women aged 55–79 years; early (<6 years) vs. late (≥10 years) postmenopause; oral estradiol 1 mg/day (or transdermal 50 µg/day) with vaginal progesterone in women with a uterus | Early initiation of estradiol slowed progression of subclinical atherosclerosis; no benefit observed with late initiation, supporting the timing hypothesis |

| Bergendal et al., 2016 [44] | Population-based case–control study | Peri- and postmenopausal women using local or systemic hormone therapy | Systemic oral estrogen associated with increased VTE risk; transdermal and local estrogen showed lower or no increased VTE risk |

| Goldštajn et al., 2023 [45] | Systematic review | Postmenopausal women; comparison of oral vs. transdermal estrogen at standard therapeutic doses | Transdermal HRT associated with more favorable cardiovascular and thrombotic risk profile compared with oral therapy |

| Straczek et al., 2005 [46] | Case–control study | Postmenopausal women, including carriers of prothrombotic mutations; oral vs. transdermal estrogen | Oral estrogen markedly increased VTE risk, especially in women with thrombophilic mutations; transdermal estrogen showed no significant risk increase |

| Wakatsuki et al., 2002 [47] | Randomized controlled trial | Postmenopausal women; oral CEE vs. transdermal estradiol (standard doses) | Oral estrogen increased LDL particle size but also oxidative susceptibility; transdermal estrogen had more neutral metabolic effects |

| Cushman et al., 2004 [49] | Randomized controlled trial (WHI) | Women aged 50–79 years; CEE 0.625 mg/day + MPA 2.5 mg/day | Combined HRT significantly increased risk of venous thrombosis, particularly during the first year of therapy |

| Shimbo et al., 2014 [50] | Randomized controlled trial (WHI) | Postmenopausal women 50–79 years, mean 12–13 years since menopause; WHI participants without prior CVD; CEE 0.625 mg/day ± MPA 2.5 mg/day; BP measured longitudinally | Hormone therapy slightly increased mean blood pressure and blood pressure variability, with potential implications for cardiovascular risk |

| de Lauzon-Guillain et al., 2009 [52] | Prospective cohort study | Postmenopausal women using predominantly transdermal HRT | HRT associated with reduced risk of new-onset diabetes, particularly with transdermal estrogen |

| Study | Study Design | Population Characteristics | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhao et al., 2018 [59] | Prospective cohort | Postmenopausal women without baseline cardiovascular disease, predominantly aged ≥ 60 years, recruited from a large US community-based cohort | Higher endogenous estradiol associated with increased CVD risk |

| Bhullar et al., 2024 [60] | Narrative review | Women of reproductive age using combined and progestin-only oral contraceptives | Increased risk of VTE, hypertension, MI, and stroke with combined OCs |

| Skafar et al., 1997 [61] | Clinical review | Women across the lifespan, including premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal age groups | Estrogen protective; progestins show heterogeneous CV effects |

| Thomas and Pang, 2013 [62] | Experimental/review | Animal models and adult human cardiovascular cell lines | Progesterone shows rapid protective effects |

| Sidney et al., 2004 [64] | Case–control | Premenopausal women, most aged 18–44 years | Low-estrogen combined oral contraceptives were associated with higher risk of venous thromboembolism compared with nonusers |

| Lidegaard et al., 2009 [65] | Nationwide cohort | Danish women aged 15–49 years without prior thromboembolism | Hormonal contraception, particularly combined oral contraceptives with higher estrogen doses and certain progestin types, was associated with a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolism in women aged 15–49, though absolute risk remained low |

| Oedingen et al., 2018 [66] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Women of reproductive age using COCs (typically 15–49 years) | Higher VTE risk with newer progestins and higher EE doses |

| Cameron et al., 2023 [67] | Narrative review | Women of reproductive age and early perimenopause | Oral contraceptives associated with modest BP increases |

| Park and Kim, 2013 [68] | Cross-sectional | Korean women aged 20–49 years | OC use associated with hypertension and prehypertension |

| Weir, 1982 [69] | Interventional | Adult women, mainly 20–40 years, with OC-induced hypertension | BP reduction after switching to low-dose formulations |

| Roach et al., 2015 [70] | Systematic review (Cochrane) | Premenopausal women, mostly <50 years | Increased risk of MI and ischemic stroke |

| Rosenberg et al., 1980 [71] | Case–control | Premenopausal women aged approximately 20–44 years | OC use increases nonfatal MI risk |

| Stampfer et al., 1988 [72] | Prospective cohort | Healthy women, baseline age mainly 30–55 years | No increased long-term CVD risk after past OC use |

| Dou et al., 2023 [73] | Prospective cohort | Middle-aged women, mean age ~55–60 years (UK Biobank) | OC use associated with lower all-cause mortality |

| Fan et al., 2024 [74] | Prospective cohort | Women of reproductive age, generally 20–49 years | Reproductive factors (parity, age at menarche/menopause) and hormonal contraceptive use were associated with differential risk of type 2 diabetes, with genetic susceptibility further modifying this risk; certain combinations of reproductive history and genetic profile significantly increased diabetes incidence |

| Snell-Bergeon et al., 2008 [75] | Observational cohort | Women with type 1 diabetes, mean age ~40 years | Hormonal contraception linked to coronary calcium progression |

| Staudt et al., 2024 [76] | Longitudinal cohort | Healthy adolescent girls aged ~14–19 years | Adolescent OC users exhibited changes in lipid metabolism, suggesting early monitoring of lipid profiles may be warranted during hormonal contraceptive use |

| Skouby et al., 2005 [78] | Randomized controlled trial | Healthy women aged ~18–40 years | Lower EE dose improved lipid and glucose metabolism |

| Luo et al., 2021 [80] | Prospective cohort | Adult women, mainly 40–60 years at baseline | OC use associated with incident heart failure |

| Stachenfeld and Keefe, 2002 [81] | Experimental | Healthy adult women | Estrogen influenced AVP secretion and fluid balance |

| Tepper et al., 2025 [82] | Systematic review | Women of reproductive age using progestin-only contraception | No significant increase in thrombosis risk |

| Cockrum et al., 2022 [84] | Case–control | Women aged 18–49 years | VTE risk differed by progestogen type; higher for desogestrel and drospirenone compared with levonorgestrel |

| Glisic et al., 2018 [85] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Women of reproductive age using POPs | POP use not associated with adverse cardiometabolic outcomes; generally neutral effects on BP, lipids, and glucose |

| Yonis et al., 2025 [86] | Nationwide prospective cohort | Women aged 15–49 years | Hormonal contraception slightly increased risk of stroke and MI; absolute risk low, influenced by age, smoking, and hormone type |

| Letnar et al., 2024 [87] | Cohort study | Women of reproductive age using LNG-IUD | No increased ischemic stroke risk |

| WHO Collaborative Study, 1998 [88] | Multicenter case–control | Women aged 15–49 years from multiple countries | Minimal CVD risk with progestogen-only methods |

| Hussain, 2004 [89] | Literature review | Women of reproductive age using POPs | No consistent BP elevation |

| Kimble et al., 2020 [90] | Prospective phase 3 trial | Healthy women aged 18–45 years | Favorable safety and BP profile |

| Oelkers et al., 1995 [91] | Interventional study | Adult women of reproductive age | Drospirenone OC lowered renin–aldosterone activity, modestly reduced BP, and maintained neutral/favorable metabolic profile |

| Barkfeldt et al., 2001 [92] | Comparative trial | Women aged ~18–45 years | Desogestrel POP caused slightly higher total cholesterol and LDL increases than levonorgestrel; HDL and triglycerides largely unchanged |

| Wang et al., 2016 [93] | Cross-sectional and longitudinal | Population-based cohort, mostly <50 years | HC use altered systemic metabolism, affecting lipids and amino acids; effects dependent on contraceptive type and duration |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kampka, Z.; Balwierz-Podgórna, M.; Wybraniec, M.T. Sex Hormone Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Medicina 2026, 62, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010134

Kampka Z, Balwierz-Podgórna M, Wybraniec MT. Sex Hormone Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010134

Chicago/Turabian StyleKampka, Zofia, Magdalena Balwierz-Podgórna, and Maciej T. Wybraniec. 2026. "Sex Hormone Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk" Medicina 62, no. 1: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010134

APA StyleKampka, Z., Balwierz-Podgórna, M., & Wybraniec, M. T. (2026). Sex Hormone Supplementation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Medicina, 62(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010134