Comparison of Effects of General Versus Spinal Anesthesia on Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates After Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy Surgery: Retrospective Cohort Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

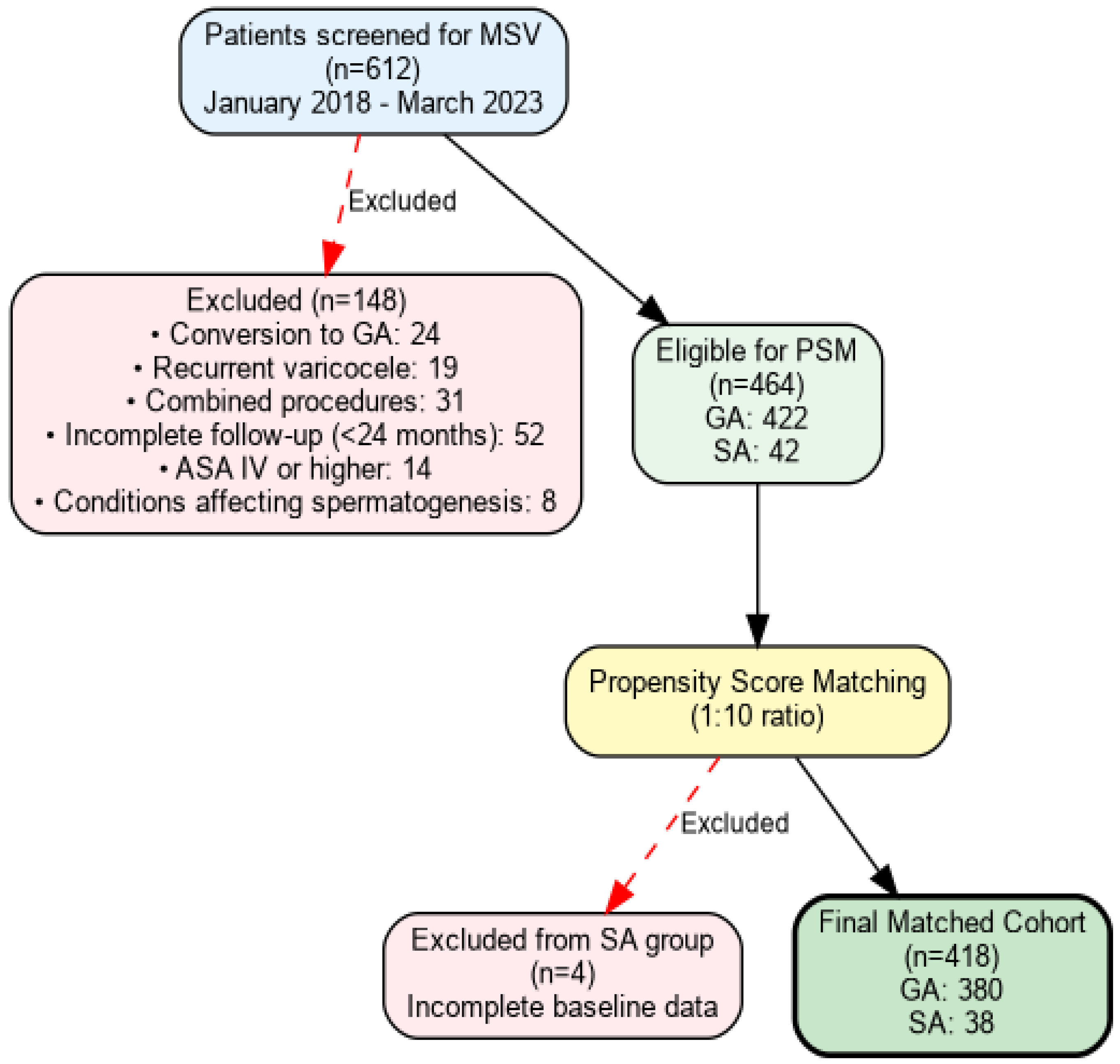

2.2. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.3. Propensity Score Matching Methodology

2.4. Anesthetic Management and Surgical Technique

2.5. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient’s Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Perioperative Outcomes and Complications

3.3. Recovery Parameters

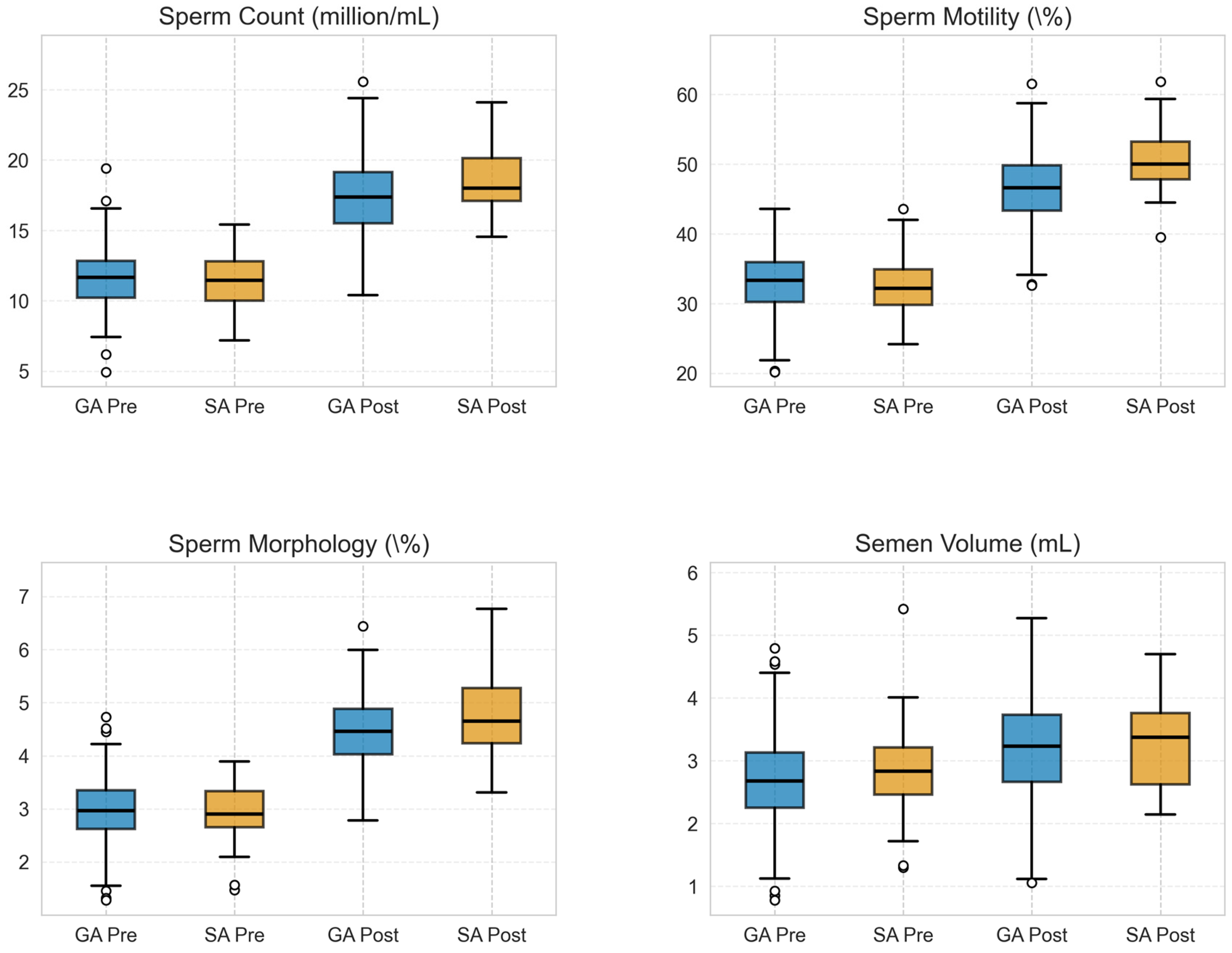

3.4. Comparison of Pre-Versus Postoperative Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ART | Assisted reproductive technology |

| ASA | American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| GA | General anesthesia |

| IVF | In vitro fertilization |

| MSV | Microscopic subinguinal varicocelectomy |

| SA | Spinal anesthesia |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Damsgaard, J.; Joensen, U.N.; Carlsen, E.; Erenpreiss, J.; Jensen, M.B.; Matulevicius, V.; Zilaitiene, B.; Olesen, I.A.; Perheentupa, A.; Punab, M.; et al. Varicocele Is Associated with Impaired Semen Quality and Reproductive Hormone Levels: A Study of 7035 Healthy Young Men from Six European Countries. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.F.S.; Østergren, P.; Dupree, J.M.; Ohl, D.A.; Sønksen, J.; Fode, M. Varicocele and male infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017, 14, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanin, A.M.; Ahmed, H.H.; Kaddah, A.N. A global view of the pathophysiology of varicocele. Andrology 2018, 6, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garolla, A.; Torino, M.; Miola, P.; Caretta, N.; Pizzol, D.; Menegazzo, M.; Bertoldo, A.; Foresta, C. Twenty-four-hour monitoring of scrotal temperature in obese men and men with a varicocele as a mirror of spermatogenic function. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Tian, J.; Du, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Open non-microsurgical, laparoscopic or open microsurgical varicocelectomy for male infertility: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Pan, C.; Li, J.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, G.; Bai, S.; Chai, J.; Shan, L. Prospective comparison of local anesthesia with general or spinal anesthesia in patients treated with microscopic varicocelectomy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungwirth, A.; Gögüs, C.; Hauser, G.; Gomahr, A.; Schmeller, N.; Aulitzky, W.; Frick, J. Clinical outcome of microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy in infertile men. Andrologia 2001, 33, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmar, J.L.; Kim, Y. Subinguinal microsurgical varicocelectomy: A technical critique and statistical analysis of semen and pregnancy data. J. Urol. 1994, 152, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.B.; Desai, N.R.; Agarwal, A. Varicocele repair: Does it still have a role in infertility treatment? Curr. Opin. Obs. Gynecol. 2008, 20, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Deepinder, F.; Cocuzza, M.; Agarwal, R.; Short, R.A.; Sabanegh, E.; Marmar, J.L. Efficacy of varicocelectomy in improving semen parameters: New meta-analytical approach. Urology 2007, 70, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivascu, R.; Torsin, L.I.; Hostiuc, L.; Nitipir, C.; Corneci, D.; Dutu, M. The Surgical Stress Response and Anesthesia: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra, K.; Dubravka, R.; Ljiljana, P.; Maja, P.; Ksenija, C. Oxidative stress under general intravenous and inhalation anaesthesia. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 2020, 71, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Haroutounian, S. Postoperative opioids, endocrine changes, and immunosuppression. Pain. Rep. 2018, 3, e640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Guan, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z. Modified Inguinal Microscope-Assisted Varicocelectomy under Local Anesthesia: A Non-randomised Controlled Study of 3565 Cases. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.J.; Rothman, K.J.; Bateman, B.T.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Huybrechts, K.F. A Propensity-score-based Fine Stratification Approach for Confounding Adjustment When Exposure Is Infrequent. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadihasanoglu, M.; Karaguzel, E.; Kacar, C.K.; Arıkan, M.S.; Yapici, M.E.; Türkmen, N. Local or spinal anesthesia in subinguinal varicocelectomy: A prospective randomized trial. Urology 2012, 80, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalias, G.A.; Liatsikos, E.N.; Nikiforidis, G.; Siablis, D. Treatment of varicocele for male infertility: A comparative study evaluating currently used approaches. Eur. Urol. 1998, 34, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayan, S.; Kadioglu, T.C.; Tefekli, A.; Kadioglu, A.; Tellaloglu, S. Comparison of results and complications of high ligation surgery and microsurgical high inguinal varicocelectomy in the treatment of varicocele. Urology 2000, 55, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ji, Z.G. Microsurgery Versus Laparoscopic Surgery for Varicocele: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Investig. Surg. 2020, 33, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopps, C.V.; Lemer, M.L.; Schlegel, P.N.; Goldstein, M. Intraoperative varicocele anatomy: A microscopic study of the inguinal versus subinguinal approach. J. Urol. 2003, 170, 2366–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, A.S.; Baird, D.D.; Weinberg, C.R.; Shore, D.L.; Shy, C.M.; Wilcox, A.J. Reduced fertility among women employed as dental assistants exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 327, 993–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Medikondu, H.; Jain, D.; Veeranki, S.; Hussain, S.Y.; Kashyap, L.; Mahey, R. Effect of Nitrous Oxide During Oocyte Retrieval on In Vitro Fertilization Outcomes: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2025, 17, e89146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaamoo, S.; Azmoodeh, A.; Yousefshahi, F.; Berjis, K.; Ahmady, F.; Qods, K.; Mirmohammad, K.; Hani, M. Does Spinal Analgesia have Advantage over General Anesthesia for Achieving Success in In-Vitro Fertilization? Oman Med. J. 2014, 29, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmude, A.; Agha’AMou, S.; Yousefshahi, F.; Berjis, K.; Mirmohammad, K.; Hani, M.; Ghods, K.; Dabbagh, A. Pregnancy outcome using general anesthesia versus spinal anesthesia for in vitro fertilization. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2013, 3, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mouzon, J.; Goossens, V.; Bhattacharya, S.; Castilla, J.A.; Ferraretti, A.P.; Korsak, V.; Kupka, M.; Nygren, K.G.; Andersen, A.N. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2006: Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circeo, L.; Grow, D.; Kashikar, A.; Gibson, C. Prospective, observational study of the depth of anesthesia during oocyte retrieval using a total intravenous anesthetic technique and the Bispectral index monitor. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsota, P.; Kaminioti, E.; Kostopanagiotou, G. Anesthesia Related Toxic Effects on In Vitro Fertilization Outcome: Burden of Proof. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 475362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahos, N.F.; Giannakikou, I.; Vlachos, A.; Vitoratos, N. Analgesia and anesthesia for assisted reproductive technologies. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2009, 105, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonen, O.; Shulman, A.; Ghetler, Y.; Shapiro, A.; Judeiken, R.; Beyth, Y.; Ben-Nun, I. The impact of different types of anesthesia on in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer treatment outcome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 1995, 12, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balki, M.; Carvalho, J.C. Intraoperative nausea and vomiting during cesarean section under regional anesthesia. Int. J. Obs. Anesth. 2005, 14, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | General Anesthesia (n = 380) | Spinal Anesthesia (n = 38) | p Value | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age and anthropometric data | ||||

| Age (years) | 34.15 ± 9.61 | 33.55 ± 9.66 | 0.711 | 0.062 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.42 ± 4.85 | 27.79 ± 5.03 | 0.096 | 0.089 |

| ASA physical status, n (%) | ||||

| I | 186 (48.9) | 17 (44.7) | 0.876 | 0.074 |

| II | 156 (41.1) | 17 (44.7) | ||

| III | 38 (10.0) | 4 (10.5) | ||

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Smoking | 112 (29.5) | 11 (28.9) | 0.946 | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | 68 (17.9) | 7 (18.4) | 0.936 | 0.013 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (11.1) | 4 (10.5) | 0.919 | 0.019 |

| Dyslipidemia | 54 (14.2) | 5 (13.2) | 0.866 | 0.029 |

| Varicocele characteristics, n (%) | ||||

| Grade II | 228 (60.0) | 22 (57.9) | 0.924 | 0.058 |

| Grade III | 152 (40.0) | 16 (42.1) | ||

| Bilateral | 342 (90.0) | 34 (89.5) | 0.918 | 0.016 |

| Preoperative semen parameters | ||||

| Sperm Count (million/mL) | 11.54 ± 2.04 | 11.56 ± 2.06 | 0.931 | 0.033 |

| Sperm Motility (%) | 32.65 ± 4.31 | 32.62 ± 4.25 | 0.932 | 0.007 |

| Sperm Morphology (%) | 2.97 ± 0.56 | 2.99 ± 0.62 | 0.810 | 0.041 |

| Semen Volume (mL) | 2.70 ± 0.70 | 2.84 ± 0.68 | 0.082 | 0.068 |

| Duration of infertility | ||||

| Months, median (IQR) | 24 (18–36) | 26 (19–38) | 0.842 | 0.52 |

| Complications | General Anesthesia (n = 380) | Spinal Anesthesia (n = 38) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative Events, n (%) | |||

| Bradycardia (<50 bpm) | 19 (5.0) | 3 (7.9) | 0.442 |

| Hypotension (MAP < 50 mmHg) | 24 (6.3) | 1 (2.6) | 0.714 |

| Bleeding (>50 mL) | 13 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.614 |

| No complications | 324 (85.3) | 34 (89.5) | 0.624 |

| Postoperative Events, n (%) | |||

| Nausea/Vomiting | 62 (16.3) | 8 (21.1) | 0.605 |

| PDPH | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Urinary retention | 7 (1.8) | 6 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| Scrotal hematoma | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.721 |

| Recovery Parameters | |||

| Time to ambulation (h) | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (h) | 28.4 ± 6.3 | 24.7 ± 5.1 | 0.002 |

| Morphine consumption in the first 24 h of the postoperative period (mg) | 8.4 ± 5.7 | 2.8 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| VAS pain score at 6 h | 3.8 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| VAS pain score at 24 h | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.004 |

| Parameter | General Anesthesia (n = 380) | Spinal Anesthesia (n = 38) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postoperative values (at 24th month after surgery) | ||||

| Sperm Count (million/mL) | 17.48 ± 2.63 | 18.29 ± 2.53 | 0.81 (−0.09 to 1.71) | 0.076 |

| Sperm Motility (%) | 46.39 ± 4.73 | 49.55 ± 4.74 | 3.16 (1.51 to 4.81) | 0.0002 |

| Sperm Morphology (%) | 4.45 ± 0.64 | 4.67 ± 0.71 | 0.22 (−0.01 to 0.45) | 0.058 |

| Semen Volume (mL) | 3.18 ± 0.72 | 3.30 ± 0.66 | 0.12 (−0.29 to 0.31) | 0.096 |

| Improvement from Baseline (%) * | ||||

| Sperm Count | 56.84 ± 28.41 | 63.63 ± 30.12 | 6.79 (−5.71 to 19.29) | 0.285 |

| Sperm Motility | 44.76 ± 21.83 | 54.46 ± 23.65 | 9.70 (1.12 to 18.28) | 0.027 |

| Sperm Morphology | 55.35 ± 58.42 | 63.95 ± 61.78 | 8.60 (−14.52 to 31.72) | 0.468 |

| Semen Volume | 17.77 ± 32.45 | 16.19 ± 31.87 | −1.58 (−16.52 to 8.94) | 0.553 |

| Pregnancy rate, % (n/N) | 32.9 (125/380) | 42.1 (16/38) | 9.2 | 0.031 |

| Achievement of WHO reference values, n (%) | ||||

| Sperm Count ≥ 15 million/mL | 312 (82.1) | 34 (89.5) | N/A | 0.368 |

| Motility ≥ 40% | 342 (90.0) | 37 (97.4) | N/A | 0.229 |

| Morphology ≥ 4% | 289 (76.1) | 32 (84.2) | N/A | 0.318 |

| Volume ≥ 1.5 mL | 371 (97.6) | 37 (97.4) | N/A | 0.947 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Özdemir, L.; Sagün, A.; Başaranoğlu, M.; Sevim, E.T.; Azizoğlu, M.; Akbay, E. Comparison of Effects of General Versus Spinal Anesthesia on Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates After Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy Surgery: Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Medicina 2026, 62, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010133

Özdemir L, Sagün A, Başaranoğlu M, Sevim ET, Azizoğlu M, Akbay E. Comparison of Effects of General Versus Spinal Anesthesia on Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates After Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy Surgery: Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010133

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzdemir, Levent, Aslınur Sagün, Mert Başaranoğlu, Elif Tuna Sevim, Mustafa Azizoğlu, and Erdem Akbay. 2026. "Comparison of Effects of General Versus Spinal Anesthesia on Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates After Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy Surgery: Retrospective Cohort Analysis" Medicina 62, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010133

APA StyleÖzdemir, L., Sagün, A., Başaranoğlu, M., Sevim, E. T., Azizoğlu, M., & Akbay, E. (2026). Comparison of Effects of General Versus Spinal Anesthesia on Spermiogram Parameters and Pregnancy Rates After Microscopic Subinguinal Varicocelectomy Surgery: Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Medicina, 62(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010133