Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Cirrhosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Portal Vein Thrombosis in Liver Cirrhosis

3. Hepatic Vein Thrombosis in Liver Cirrhosis

4. Thrombosis in Patients After Liver Transplantation

4.1. Hepatic Artery Thrombosis

4.2. Portal Vein Thrombosis

5. Bleeding in Liver Cirrhosis

5.1. Spontaneous Hemostasis-Related Bleeding

5.2. Role of Possible Prophylactic Therapy in Spontaneous Bleeding

5.3. Portal Hypertension-Related Bleeding

6. Invasive Procedures in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

Assessment and Treatment of Coagulopathy

7. Treatment of Severe Thrombocytopenia

7.1. Platelet Transfusion

7.2. Interventional Management

- (a)

- Splenectomy

- (b)

- Partial splenic embolization (PSE)

- (c)

- Radiofrequency ablation of the spleen

- (d)

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and other shunt procedures

7.3. Pharmacological Therapies

- (a)

- Thrombopoietin receptor agonists

- (b)

- Recombinant TPO and human cytokines

- (c)

- Correction of underlying causes

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEG | Thromboelastogram |

| vWF | von Willebrand factor |

| TPO | Thrombopoietin |

| CLD | Chronic liver disease |

| tPA | Tissue plasminogen activator |

| PVT | Portal venous thrombosis |

| cm/s | Centimetre per second |

| CTP | Child Turcotte Pugh |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| CD | Color Doppler |

| MSCTA | Multislice computed tomography angiography |

| MRA | Magnetic resonance angiography |

| CEUS | Contrast-enhanced ultrasound |

| AC | Anticoagulant therapy |

| RR | Risk ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| p | p-value |

| LMWH | Low-molecular-weight heparin |

| DOACs | Direct oral anticoagulants |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| OLT | Orthotopic liver transplantation |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| TIPS | Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt |

| EGDS | Esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| BCS | Budd-Chiari syndrome |

| MPN | Myeloproliferative neoplasm |

| DUS | Doppler ultrasound |

| VKAs | Vitamin K antagonists |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| LT | Liver transplantation |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| HAT | Hepatic artery thrombosis |

| HVT | Hepatic vein thrombosis |

| IVC | Inferior vena cava |

| RI | Resistive index |

| LDLT | Living donor liver transplantation |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| CNIs | Calcineurin inhibitors |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 enzyme |

| INR | International normalized ratio |

| ICH | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 index |

| MHE | Minimal hepatic encephalopathy |

| d | Days |

| aPTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| UGIB | Upper gastrointestinal bleeding |

| FFP | Fresh frozen plasma |

| HVPG | Hepatic venous pressure gradient |

| mmHg | Millimeters of mercury |

| EASL | European Association for the Study of Liver |

| rFVIIa | Recombinant factor VIIa |

| h | Hour |

| PEG | Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy |

| LVP | Large volume paracentesis |

| AGA | American Gastroenterological Association |

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| NOACs | Novel oral anticoagulants |

| EVL | Endoscopic variceal band ligation |

| EV | Esophageal varices |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| TEE | Transesophageal echocardiography |

| LC | Liver cirrhosis |

| Plts | Platelets |

| PT | Prothrombin time |

| BT | Bleeding time |

| ROTEM | Rotational thromboelastometry |

| CT (ROTEM) | Clotting time |

| CFT | Clot formation time |

| mm | Millimeter |

| MA | Maximum amplitude |

| MCF | Maximum clot firmness |

| LY30 | Clot lysis at 30 min |

| ML | Maximum lysis |

| PCC | Prothrombin complex |

| SOC | Standard of care |

| SMD | Standardized mean difference |

| mg | Milligram |

| IU | International unit |

| po | Per os |

| iv | Intravenous |

| g | Gram |

| mL | Milliliter |

| kg | Kilogram |

| BW | Body weight |

| mg/dL | Milligram per deciliter |

| µL | Microliter |

| L | Liter |

| PSE | Partial splenic embolization |

| RFA | Radiofrequency ablation |

| TPO-RAs | Thrombopoietin receptor agonists |

References

- Winther-Larsen, A.; Sandfeld-Paulsen, B.; Hvas, A.M. New Insights in Coagulation and Fibrinolysis in Patients with Primary Brain Cancer: A Systematic Review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 48, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokarz-Deptuła, B.; Baraniecki, Ł.; Palma, J.; Stosik, M.; Syrenicz, A.; Kołacz, R.; Deptuła, W. Platelets and Their Role in Immunity: Formation, Activation and Activity, and Biologically Active Substances in Their Granules and Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Inflamm. 2025, 2025, 8878764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovna Gabrilchak, A.; Anatolievna Gusyakova, O.; Aleksandrovich Antipov, V.; Alekseevna Medvedeva, E.; Leonidovna Tukshumskaya, L. A modern overview of the process of platelet formation (thrombocytopoiesis) and its dependence on several factors. Biochem. Med. 2024, 34, 030503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, A.P.; Nikols, E.; Freire, D.; Machlus, K.R. The pathobiology of platelet and megakaryocyte extracellular vesicles: A (c)lot has changed. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 20, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, T.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Magnusson, M.; Roberts, L.; Stanworth, S.; Thachil, J.; Tripodi, A. The concept of rebalanced hemostasis in patients with liver disease: Communication from the ISTH SSC working group on hemostatic management of patients with liver disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1116–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginès, P.; Krag, A.; Abraldes, J.G.; Solà, E.; Fabrellas, N.; Kamath, P.S. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2021, 398, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northup, P.G.; Garcia-Pagan, J.C.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Intagliata, N.M.; Superina, R.A.; Roberts, L.N.; Lisman, T.; Valla, D.C. Vascular liver disorders, portal vein thrombosis, and procedural bleeding in patients with liver disease: 2020 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2021, 73, 366–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Rodríguez, D.; Narváez Chávez, G.A.; Rodríguez Ramos, S.T.; Orera Pérez, Á.; Barrueco-Francioni, J.E.; Merino García, P. SEMICYUC Working Groups on Critical Digestive Disease, and on Hemotherapy, Hematology, and Critical Oncology. Coagulation disorders in patients with chronic liver disease: A narrative review. Med. Intensiv. 2025, 502216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, T. Bleeding and Thrombosis in Patients with Cirrhosis: What’s New? Hemasphere 2023, 7, e886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopapas, A.A.; Savopoulos, C.; Skoura, L.; Goulis, I. Anticoagulation in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: Friend or Foe? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, M.; Tardugno, M.; Lancellotti, S.; Ferretti, A.; Ponziani, F.R.; Riccardi, L.; Zocco, M.A.; De Magistris, A.; Santopaolo, F.; Pompili, M.; et al. ADAMTS-13/von Willebrand factor ratio: A prognostic biomarker for portal vein thrombosis in compensated cirrhosis. A prospective observational study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 1672–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, P.; Terracciani, F.; Di Pasquale, G.; Esposito, M.; Picardi, A.; Vespasiani-Gentilucci, U. Thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease: Physiopathology and new therapeutic strategies before invasive procedures. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4061–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, H.; Beppu, T.; Shirabe, K.; Maehara, Y.; Baba, H. Management of thrombocytopenia due to liver cirrhosis: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, M.; Fujimura, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Ishizashi, H.; Kato, S.; Matsuyama, T.; Isonishi, A.; Ishikawa, M.; Yagita, M.; Morioka, C.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of ADAMTS13 in patients with liver cirrhosis. Thromb. Haemost. 2008, 99, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkata, C.; Kashyap, R.; Farmer, J.C.; Afessa, B. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with sepsis: Incidence, risk factors, and its association with clinical outcome. J. Intensive Care 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, S.; Mitchell, O.; Feldman, D.; Diakow, M. The pathophysiology of thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease. Hepatic Med. 2016, 8, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aster, R.H. Pooling of platelets in the spleen: Role in the pathogenesis of “hypersplenic” thrombocytopenia. J. Clin. Investig. 1966, 45, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandl, J.H.; Aster, R.H. Increased splenic pooling and the pathogenesis of hypersplenism. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1967, 253, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetto, A.; Campello, E.; Toffanin, S.; Russo, F.P.; Senzolo, M.; Simioni, P. Mean platelet volume is not a useful prognostic biomarker in patients with cirrhosis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 1576–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, J.; Lisman, T.; Quehenberger, P.; Hell, L.; Schwabl, P.; Scheiner, B.; Bucsics, T.; Nieuwland, R.; Ay, C.; Trauner, M.; et al. Intraperitoneal Activation of Coagulation and Fibrinolysis in Patients with Cirrhosis and Ascites. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkrief, L.; Hernandez-Gea, V.; Senzolo, M.; Albillos, A.; Baiges, A.; Berzigotti, A.; Bureau, C.; Murad, S.D.; De Gottardi, A.; Durand, F.; et al. Portal vein thrombosis: Diagnosis, management, and endpoints for future clinical studies. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 859–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzolo, M.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Garcia-Pagan, J.C. Current knowledge and management of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turon, F.; Driever, E.G.; Baiges, A.; Cerda, E.; García-Criado, Á.; Gilabert, R.; Bru, C.; Berzigotti, A.; Nuñez, I.; Orts, L.; et al. Predicting portal thrombosis in cirrhosis: A prospective study of clinical, ultrasonographic and hemostatic factors. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Shen, Y.; Chen, J.; Ruan, Z.; Hua, L.; Wang, K.; Xi, X.; Mao, J. The critical role of platelets in venous thromboembolism: Pathogenesis, clinical status, and emerging therapeutic strategies. Blood Rev. 2025, 74, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, F.J.; Ziccardi, M.R.; McCauley, M.D. Virchow’s Triad and the Role of Thrombosis in COVID-Related Stroke. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 769254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, B.L.; Sarin, S.K. Management of Portal Vein Thrombosis in Cirrhosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2024, 44, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, L.; Gao, F.; An, Y.; Yin, Y.; Guo, X.; Nery, F.G.; Yoshida, E.M.; Qi, X. Epidemiology of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 104, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, F.; Chevret, S.; Condat, B.; de Raucourt, E.; Boudaoud, L.; Rautou, P.E.; Plessier, A.; Roulot, D.; Chaffaut, C.; Bourcier, V.; et al. Causes and consequences of portal vein thrombosis in 1,243 patients with cirrhosis: Results of a longitudinal study. Hepatology 2015, 61, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocco, M.A.; Di Stasio, E.; De Cristofaro, R.; Novi, M.; Ainora, M.E.; Ponziani, F.; Riccardi, L.; Lancellotti, S.; Santoliquido, A.; Flore, R.; et al. Thrombotic risk factors in patients with liver cirrhosis: Correlation with MELD scoring system and portal vein thrombosis development. J. Hepatol. 2009, 51, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nery, F.; Correia, S.; Macedo, C.; Gandara, J.; Lopes, V.; Valadares, D.; Ferreira, S.; Oliveira, J.; Gomes, M.T.; Lucas, R.; et al. Nonselective beta-blockers and the risk of portal vein thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis: Results of a prospective longitudinal study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 49, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Guo, X.; De Stefano, V.; Silva-Junior, G.; Goyal, H.; Bai, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Qi, X. Nonselective beta-blockers and development of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J.I.; Carrera, I.G.; Puente, Á.; Cuadrado, A.; Huelin, P.; Tato, C.Á.; Fernández, P.Á.; Montes, M.D.R.P.; Céspedes, J.N.; López, A.B.; et al. Portal Thrombosis in Cirrhosis: Role of Thrombophilic Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, B.; Northup, P.G.; Gruber, A.B.; Semmler, G.; Leitner, G.; Quehenberger, P.; Thaler, J.; Ay, C.; Trauner, M.; Reiberger, T.; et al. The impact of ABO blood type on the prevalence of portal vein thrombosis in patients with advanced chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier-Hourmand, I.; Repesse, Y.; Nahon, P.; Chaffaut, C.; Dao, T.; Nguyen, T.T.N.; Marcellin, P.; Roulot, D.; De Ledinghen, V.; Pol, S.; et al. ABO blood group does not influence Child-Pugh A cirrhosis outcome: An observational study from CIRRAL and ANRS CO12 CIRVIR cohorts. Liver Int. 2022, 42, 1386–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadani, S.; Partovi, S.; Levitin, A.; Zerona, N.; Sengupta, S.; D’Amico, G.; Diago Uso, T.; Menon, K.V.N.; Quintini, C. Narrative review of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management from an interventional radiology perspective. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2022, 12, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.P.E.; Lim, J.K.; Francis, F.F.; Ahn, J. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Portal Vein Thrombosis in Patients with Cirrhosis: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Vaidya, A.; Agrawal, D.; Varghese, J.; Patel, R.K.; Tripathy, T.; Singh, A.; Das, S. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for differentiation of benign vs. malignant portal vein thrombosis in hepatocellular carcinoma-A systematic review a meta-analysis. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 27, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Guo, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Tacke, F.; Primignani, M.; He, Y.; Yin, Y.; Yi, F.; Qi, X. Natural history and predictors associated with the evolution of portal venous system thrombosis in liver cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Xu, X.; De Stefano, V.; Plessier, A.; Noronha Ferreira, C.; Qi, X. Anticoagulation Favors Thrombus Recanalization and Survival in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: Results of a Meta-Analysis. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 495–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffredo, L.; Pastori, D.; Farcomeni, A.; Violi, F. Effects of Anticoagulants in Patients with Cirrhosis and Portal Vein Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.H.; Liew, Z.H.; Ng, G.K.; Liu, H.T.; Tam, Y.C.; De Gottardi, A.; Wong, Y.J. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus vitamin K antagonist for portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.H.; Dong, W.G.; Tan, X.P.; Xu, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Efficacy and safety study of direct-acting oral anticoagulants for the treatment of chronic portal vein thrombosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 32, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, M.; Yu, S.; Xia, H.; Yu, W.; Huang, K.; Chen, Y. Comparison of the efficacy and safety between rivaroxaban and dabigatran in the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.J.; Yin, F.Q.; Ma, Y.T.; Gao, T.Y.; Tao, Y.T.; Liu, X.; Shen, X.F.; Zhang, C. Administration of anticoagulation strategies for portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis: Network meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1462338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, A.; Campo, L.D.; Piscaglia, F.; Scheiner, B.; Han, G.; Violi, F.; Ferreira, C.N.; Téllez, L.; Reiberger, T.; Basili, S.; et al. Anticoagulation improves survival in patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis: The IMPORTAL competing-risk meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vascular diseases of the liver. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessier, A.; Darwish-Murad, S.; Hernandez-Guerra, M.; Consigny, Y.; Fabris, F.; Trebicka, J.; Heller, J.; Morard, I.; Lasser, L.; Langlet, P.; et al. Acute portal vein thrombosis unrelated to cirrhosis: A prospective multicenter follow-up study. Hepatology 2010, 51, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Franchis, R.; Bosch, J.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Reiberger, T.; Ripoll, C.; Baveno VII Faculty. Baveno VII-Renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senzolo, M.; Sartori, T.M.; Rossetto, V.; Burra, P.; Cillo, U.; Boccagni, P.; Gasparini, D.; Miotto, D.; Simioni, P.; Tsochatzis, E.; et al. Prospective evaluation of anticoagulation and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the management of portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2012, 32, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.G.; Seijo, S.; Yepes, I.; Achécar, L.; Catalina, M.V.; García-Criado, A.; Abraldes, J.G.; de la Peña, J.; Bañares, R.; Albillos, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulation on patients with cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 776–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pagán, J.C.; Saffo, S.; Mandorfer, M.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Where does TIPS fit in the management of patients with cirrhosis? JHEP Rep. 2020, 2, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on TIPS. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, 177–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, R.; Vouche, M.; Baker, T.; Herrero, J.I.; Caicedo, J.C.; Fryer, J.; Hickey, R.; Habib, A.; Abecassis, M.; Koller, F.; et al. Pretransplant Portal Vein Recanalization-Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt in Patients with Complete Obliterative Portal Vein Thrombosis. Transplantation 2015, 99, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornburg, B.; Desai, K.; Hickey, R.; Hohlastos, E.; Kulik, L.; Ganger, D.; Baker, T.; Abecassis, M.; Caicedo, J.C.; Ladner, D.; et al. Pretransplantation Portal Vein Recanalization and Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt Creation for Chronic Portal Vein Thrombosis: Final Analysis of a 61-Patient Cohort. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 28, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, M.; Cavani, G.; Bonaccorso, A.; Turco, L.; Vizzutti, F.; Sartini, A.; Gitto, S.; Merighi, A.; Banchelli, F.; Villa, E.; et al. Low molecular weight heparin does not increase bleeding and mortality post-endoscopic variceal band ligation in cirrhotic patients. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, M.; Christol, C.; Plessier, A.; Corbic, M.; Péron, J.M.; Sommet, A.; Rautou, P.E.; Consigny, Y.; Vinel, J.P.; Valla, C.D.; et al. Bleeding risk of variceal band ligation in extrahepatic portal vein obstruction is not increased by oral anticoagulation. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 30, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R.; Loomba, R. Emerging role of statin therapy in the prevention and management of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and HCC. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1896–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siniscalchi, C.; Basaglia, M.; Riva, M.; Meschi, M.; Meschi, T.; Castaldo, G.; Di Micco, P. Statins Effects on Blood Clotting: A Review. Cells 2023, 12, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.D.; Muthiah, M.D.; Zheng, M.H. Statins in MASLD: Challenges and future directions. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferral, H.; Behrens, G.; Lopera, J. Budd-Chiari syndrome. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 199, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coilly, A.; Potier, P.; Broué, P.; Kounis, I.; Valla, D.; Hillaire, S.; Lambert, V.; Dutheil, D.; Hernández-Gea, V.; Plessier, A.; et al. Budd-Chiari syndrome. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2020, 44, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custo, S.; Tabone, E.; Aquilina, A.; Gatt, A.; Riva, N. Splanchnic Vein Thrombosis: The State-of-the-Art on Anticoagulant Treatment. Hamostaseologie 2024, 44, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriani, E.; Menichelli, D.; Palumbo, I.M.; Cammisotto, V.; Pastori, D.; Pignatelli, P. How to treat patients with splanchnic vein thrombosis: Recent advances. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2023, 133, 16499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; De Stefano, V.; Li, H.; Zheng, K.; Bai, Z.; Guo, X.; Qi, X. Epidemiology of Budd-Chiari syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2019, 43, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Bansal, V.; Kumar-M, P.; Sinha, S.K.; Samanta, J.; Mandavdhare, H.; Sharma, V.; Dutta, U.; Kochhar, R. Diagnostic accuracy of Doppler ultrasound, CT and MRI in Budd Chiari syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 2020, 93, 20190847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grus, T.; Lambert, L.; Grusova, G.; Banerjee, R.; Burgetova, A. Budd-Chiari syndrome. Prague Med. Rep. 2017, 118, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, V.; Gupta, P.; Sinha, S.; Dhaka, N.; Kalra, N.; Vijayvergiya, R.; Dutta, U.; Kochhar, R. Budd-Chiari syndrome: Imaging review. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20180441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliescu, L.; Toma, L.; Mercan-Stanciu, A.; Grumeza, M.; Dodot, M.; Isac, T.; Ioanitescu, S. Budd-Chiari syndrome-various etiologies and imagistic findings. A pictorial review. Med. Ultrason. 2019, 21, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rössle, M. Interventional Treatment of Budd-Chiari Syndrome. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liang, L.; Liu, J. Effect of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Traditional Anticoagulation in Budd-Chiari Syndrome. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2025, 31, 10760296251384904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.K.; Chandel, K.; Tripathy, T.; Behera, S.; Panigrahi, M.K.; Nayak, H.K.; Pattnaik, B.; Giri, S.; Dutta, T.; Gupta, S. Interventions in Budd-Chiari syndrome: An updated review. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 1307–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeve, L.D.; Valla, D.C.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; American Association for the Study Liver Diseases. Vascular disorders of the liver. Hepatology 2009, 49, 1729–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piardi, T.; Lhuaire, M.; Bruno, O.; Memeo, R.; Pessaux, P.; Kianmanesh, R.; Sommacale, D. Vascular complications following liver transplantation: A literature review of advances in 2015. World J. Hepatol. 2016, 8, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.P.; Hong, J.C.; Farmer, D.G.; Ghobrial, R.M.; Yersiz, H.; Hiatt, J.R.; Busuttil, R.W. Vascular complications of orthotopic liver transplantation: Experience in more than 4200 patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2009, 208, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi Nazari, S.; Eslamian, M.; Sheikhbahaei, E.; Zefreh, H.; Lashkarizadeh, M.M.; Shamsaeefar, A.; Kazemi, K.; Nikoupour, H.; Nikeghbalian, S.; Vatankhah, P. Early hepatic artery thrombosis treatments and outcomes: Aorto-hepatic arterial conduit interposition or revision of anastomosis? BMC Surg. 2024, 24, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekker, J.; Ploem, S.; de Jong, K.P. Early hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation: A systematic review of the incidence, outcome and risk factors. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareja, E.; Cortes, M.; Navarro, R.; Sanjuan, F.; López, R.; Mir, J. Vascular complications after orthotopic liver transplantation: Hepatic artery thrombosis. Transplant. Proc. 2010, 42, 2970–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, O.; Attia, H. Doppler ultrasonography in living donor liver transplantation recipients: Intra- and post-operative vascular complications. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 6145–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, M.; Patriquin, H. The hepatic artery studies using Doppler sonography. Ultrasound Q. 1999, 15, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciuna, I.; De Jonge, J.; Den Hoed, C.; Maan, R.; Polak, W.G.; Porte, R.J.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Procopet, B.; Darwish Murad, S. Antiplatelet Prophylaxis Reduces the Risk of Early Hepatic Artery Thrombosis Following Liver Transplantation in High-Risk Patients. Transplant. Int. 2024, 37, 13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, C.; Buccianti, S.; Risaliti, M.; Fortuna, L.; Tirloni, L.; Tucci, R.; Bartolini, I.; Grazi, G.L. Complications in Post-Liver Transplant Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Garg, I. Thrombotic complications post liver transplantation: Etiology and management. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 13, 96074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrepper, C.; Herber, A.; Weimann, A.; Siegemund, R.; Engelmann, C.; Aehling, N.; Seehofer, D.; Berg, T.; Petros, S. Safety and efficacy of direct oral anticoagulants under long-term immunosuppressive therapy after liver, kidney and pancreas transplantation. Transplant. Int. 2021, 34, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, D.M.; Tsapepas, D.; Papachristos, A.; Chang, J.H.; Martin, S.; Hardy, M.A.; McKeen, J. Direct oral anticoagulant considerations in solid organ transplantation: A review. Clin. Transplant. 2017, 31, e12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.; Bashir, B.; Chaballa, M.; Kraft, W.K. Drug interactions between direct-acting oral anticoagulants and calcineurin inhibitors during solid organ transplantation: Considerations for therapy. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, T.; Spriet, I.; Annaert, P.; Maertens, J.; Van Cleemput, J.; Vos, R.; Kuypers, D. Effect of the Direct Oral Anticoagulants Rivaroxaban and Apixaban on the Disposition of Calcineurin Inhibitors in Transplant Recipients. Ther. Drug Monit. 2017, 39, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, V.A.; O’Farrell, B.; Imber, C.; McCormack, L.; Northup, P.G.; Song, G.W.; Spiro, M.; Raptis, D.A.; Durand, F.; ERAS4OLT.org Working Group. What is the optimal management of thromboprophylaxis after liver transplantation regarding prevention of bleeding, hepatic artery, or portal vein thrombosis? A systematic review of the literature and expert panel recommendations. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36, e14629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, M.A.; Al-Theaby, A.; Tawhari, M.; Al-Shaggag, A.; Pyrke, R.; Gangji, A.; Treleaven, D.; Ribic, C. Efficacy and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants post-kidney transplantation. World J. Transplant. 2019, 9, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisman, T.; Caldwell, S.H.; Intagliata, N.M. Haemostatic alterations and management of haemostasis in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on prevention and management of bleeding and thrombosis in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 1151–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, S.; Kearon, C.; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 692–694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Catapano, J.S.; Lee, K.E.; Rumalla, K.; Srinivasan, V.M.; Cole, T.S.; Baranoski, J.F.; Winkler, E.A.; Graffeo, C.S.; Alabdly, M.; Jha, R.M.; et al. Liver Cirrhosis and Inpatient Mortality in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Propensity-Adjusted Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022, 167, e948–e952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, N.S.; Merkler, A.E.; Jesudian, A.; Kamel, H. Association between cirrhosis and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønbaek, H.; Johnsen, S.P.; Jepsen, P.; Gislum, M.; Vilstrup, H.; Tage-Jensen, U.; Sørensen, H.T. Liver cirrhosis, other liver diseases, and risk of hospitalisation for intracerebral haemorrhage: A Danish population-based case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gong, Z.; Wen, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Guo, W.; Tian, Y.; Li, Q. Association Between Liver Fibrosis and Risk of Incident Stroke and Mortality: A Large Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e037081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.S.; Navi, B.B.; Schneider, Y.; Jesudian, A.; Kamel, H. Association Between Cirrhosis and Stroke in a Nationally Representative Cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2017, 74, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.S.; Zhang, C.; Bruce, S.S.; Murthy, S.B.; Rosenblatt, R.; Liberman, A.L.; Liao, V.; Kaiser, J.H.; Navi, B.B.; Iadecola, C.; et al. Association between elevated fibrosis-4 index of liver fibrosis and risk of hemorrhagic stroke. Eur. Stroke J. 2025, 10, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.; Saleh, Z.M.; Serper, M.; Tapper, E.B. Falls are an underappreciated driver of morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2022, 20, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, E.; Córdoba, J.; Torrens, M.; Torras, X.; Villanueva, C.; Vargas, V.; Guarner, C.; Soriano, G. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with falls. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E.B.; Nikirk, S.; Parikh, N.D.; Zhao, L. Falls are common, morbid, and predictable in patients with cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustenberger, T.; Talving, P.; Lam, L.; Inaba, K.; Branco, B.C.; Plurad, D.; Demetriades, D. Liver cirrhosis and traumatic brain injury: A fatal combination based on National Trauma Databank analysis. Am. Surg. 2011, 77, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E.B.; Risech-Neyman, Y.; Sengupta, N. Psychoactive Medications Increase the Risk of Falls and Fall-related Injuries in Hospitalized Patients with Cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 1670–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Ho, C.H.; Wang, C.C.; Liang, F.W.; Wang, J.J.; Chio, C.C.; Chang, C.H.; Kuo, J.R. One-Year Mortality after Traumatic Brain Injury in Liver Cirrhosis Patients--A Ten-Year Population-Based Study. Medicine 2015, 94, e1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northup, P.G.; Lisman, T.; Roberts, L.N. Treatment of bleeding in patients with liver disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldrich, S.M.; Regal, R.E. Routine use of vitamin K in the treatment of cirrhosis-related coagulopathy: Is it A-O-K? Maybe not, we say. Pharm. Ther. 2019, 44, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Saja, M.F.; Abdo, A.A.; Sanai, F.M.; Shaikh, S.A.; Gader, A.G. The coagulopathy of liver disease: Does vitamin K help? Blood Coagul. Fibrinol 2013, 24, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Edwards, J.; Langevin, A.; Abu-Ulba, A.; Yallou, F.; Wilson, B.; Ghosh, S. Rebleeding in Variceal and Nonvariceal Gastrointestinal Bleeds in Cirrhotic Patients Using Vitamin K1: The LIVER-K Study. Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 73, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinian, N.H.; Hendrickson, J.E.; Triulzi, D.J.; Gottschall, J.L.; Michalkiewicz, M.; Chowdhury, D.; Kor, D.J.; Looney, M.R.; Matthay, M.A.; Kleinman, S.H.; et al. Contemporary Risk Factors and Outcomes of Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, A.; Kapuria, D.; Canakis, A.; Lin, H.; Amat, M.J.; Rangel Paniz, G.; Placone, N.T.; Thomasson, R.; Roy, H.; Chak, E.; et al. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in acute variceal haemorrhage: Results from a multicentre cohort study. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basili, S.; Raparelli, V.; Napoleone, L.; Talerico, G.; Corazza, G.R.; Perticone, F.; Sacerdoti, D.; Andriulli, A.; Licata, A.; Pietrangelo, A.; et al. Platelet Count Does Not Predict Bleeding in Cirrhotic Patients: Results from the PRO-LIVER Study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, G.; Shalimar; Gunjan, D.; Mahapatra, S.J.; Kedia, S.; Garg, P.K.; Nayak, B. Thromboelastography-guided Blood Product Transfusion in Cirrhosis Patients with Variceal Bleeding: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budnick, I.M.; Davis, J.P.E.; Sundararaghavan, A.; Konkol, S.B.; Lau, C.E.; Alsobrooks, J.P.; Stotts, M.J.; Intagliata, N.M.; Lisman, T.; Northup, P.G. Transfusion with Cryoprecipitate for Very Low Fibrinogen Levels Does Not Affect Bleeding or Survival in Critically Ill Cirrhosis Patients. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 121, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendtsen, F.; D’Amico, G.; Rusch, E.; de Franchis, R.; Andersen, P.K.; Lebrec, D.; Thabut, D.; Bosch, J. Effect of recombinant Factor VIIa on outcome of acute variceal bleeding: An individual patient based meta-analysis of two controlled trials. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khemichian, S.; Terrault, N.A. Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, R.; Germans, M.R.; Tjerkstra, M.A.; Vergouwen, M.D.I.; Jellema, K.; Koot, R.W.; Kruyt, N.D.; Willems, P.W.A.; Wolfs, J.F.C.; de Beer, F.C.; et al. Ultra-early tranexamic acid after subarachnoid haemorrhage (ULTRA): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HALT-IT Trial Collaborators. Effects of a high-dose 24-h infusion of tranexamic acid on death and thromboembolic events in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding (HALT-IT): An international randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desborough, M.J.; Kahan, B.C.; Stanworth, S.J.; Jairath, V. Fibrinogen as an independent predictor of mortality in decompensated cirrhosis and bleeding. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1079–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Gernsheimer, T.; Kleinman, S.; Tinmouth, A.T.; Capocelli, K.E.; Cipolle, M.D.; Cohn, C.S.; Fung, M.K.; Grossman, B.J.; et al. Platelet transfusion: A clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, Y.S. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2018, 24, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraldes, J.G.; Villanueva, C.; Bañares, R.; Aracil, C.; Catalina, M.V.; Garcia-Pagán, J.C.; Bosch, J.; Spanish Cooperative Group for Portal Hypertension and Variceal Bleeding. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelson, J.; Basso, J.E.; Rockey, D.C. Updated strategies in the management of acute variceal haemorrhage. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 37, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerini, F.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Torres, F.; Puente, Á.; Casas, M.; Vinaixa, C.; Berenguer, M.; Ardevol, A.; Augustin, S.; Llop, E.; et al. Impact of anticoagulation on upper-gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis. A retrospective multicenter study. Hepatology 2015, 62, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Tsao, G.; Abraldes, J.G.; Berzigotti, A.; Bosch, J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2017, 65, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.; Colomo, A.; Bosch, A.; Concepción, M.; Hernández-Gea, V.; Aracil, C.; Graupera, I.; Poca, M.; Álvarez-Urturi, C.; Gordillo, J.; et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisman, T.; Procopet, B. Fresh frozen plasma in treating acute variceal bleeding: Not effective and likely harmful. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1710–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intagliata, N.M.; Argo, C.K.; Stine, J.G.; Lisman, T.; Caldwell, S.H.; Violi, F.; Faculty of the 7th International Coagulation in Liver Disease. Concepts and Controversies in Haemostasis and Thrombosis Associated with Liver Disease: Proceedings of the 7th International Coagulation in Liver Disease Conference. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 118, 1491–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Janko, N.; Majeed, A.; Commins, I.; Kemp, W.; Roberts, S.K. Procedural bleeding risk, rather than conventional coagulation tests, predicts procedure related bleeding in cirrhosis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.; Amarapurkar, D.; Dharod, M.; Chandnani, M.; Baijal, R.; Kumar, P.; Jain, M.; Patel, N.; Kamani, P.; Gautam, S.; et al. Coagulopathy in cirrhosis: A prospective study to correlate conventional tests of coagulation and bleeding following invasive procedures in cirrhotics. Indian. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 34, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 406–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, J.G.; Greenberg, C.S.; Patton, H.M.; Caldwell, S.H. AGA Clinical Practice Update: Coagulation in Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, J.; Bufalini, J.; Dreer, J.; Shah, V.; King, L.; Wang, L.; Evans, M. Safety of abdominal paracentesis in hospitalised patients receiving uninterrupted therapeutic or prophylactic anticoagulants. Intern. Med. J. 2025, 55, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman, E.; Hobbs, R.A. Major bleeding after paracentesis associated with apixaban use: Two case reports. Hosp. Pharm. 2023, 58, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drolz, A.; Schramm, C.; Seiz, O.; Groth, S.; Vettorazzi, E.; Horvatits, T.; Wehmeyer, M.H.; Schramm, C.; Goeser, T.; Roesch, T.; et al. Risk factors associated with bleeding after prophylactic endoscopic variceal ligation in cirrhosis. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.S.; Yang, T.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Hou, M.C. The risk of variceal bleeding during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2022, 85, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odewole, M.; Sen, A.; Okoruwa, E.; Lieber, S.R.; Cotter, T.G.; Nguyen, A.D.; Mufti, A.; Singal, A.G.; Rich, N.E. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Incidence of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 1088–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A.; Garcia-Criado, A.; Moreno-Rojas, J.; Perez-Serrano, C.; Ubre, M.; Dieguez, I.; Panzeri, M.; Caballero, M.; Rivera, L.; Radosevic, A.; et al. A multicenter study of the risk of major bleeding in patients with and without cirrhosis undergoing percutaneous liver procedures. Liver Transplant. 2025, 31, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azer, A.; Kong, K.; Basta, D.; Modica, S.F.; Gore, A.; Gorman, E.; Sutherland, A.; Tafesh, Z.; Horng, H.; Glass, N.E. Evaluation of coagulopathy in cirrhotic patients: A scoping review of the utility of viscoelastic testing. Am. J. Surg. 2024, 227, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billoir, P.; Miranda, S.; Lévesque, H.; Benhamou, Y.; Duchez, V.L.C. Usefulness of the thrombin generation test in hypercoagulability states. Ann. Biol. Clin. 2025, 83, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitia, O.; Fouassier, M. Thrombin generation test. Rev. Med. Interne 2015, 36, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azer, A.; Panayotova, G.G.; Kong, K.; Hakakian, D.; Sheikh, F.; Gorman, E.; Sutherland, A.; Tafesh, Z.; Horng, H.; Guarrera, J.V.; et al. Clinical Application of Thromboelastography in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Single Center Experience. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 287, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, A.; Louissaint, J.; Shannon, C.; Tapper, E.B.; Lok, A.S. Viscoelastic Testing Prior to Non-surgical Procedures Reduces Blood Product Use Without Increasing Bleeding Risk in Cirrhosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 5290–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.; Subramanian, A. Thrombocytopenia in Chronic Liver Disease: Challenges and Treatment Strategies. Cureus 2021, 13, e16342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiji, H.; Ueno, Y.; Kurosaki, M.; Torimura, T.; Hatano, E.; Yatsuhashi, H.; Yamakado, K. Treatment algorithm for thrombocytopenia in patients with chronic liver disease undergoing planned invasive procedures. Hepatol. Res. 2021, 51, 1181–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronca, V.; Barabino, M.; Santambrogio, R.; Opocher, E.; Hodson, J.; Bertolini, E.; Birocchi, S.; Piccolo, G.; Battezzati, P.; Cattaneo, M.; et al. Impact of Platelet Count on Perioperative Bleeding in Patients with Cirrhosis Undergoing Surgical Treatments of Liver Cancer. Hepatol. Commun. 2022, 6, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilles, K.M.; Caldwell, S.H.; Flamm, S.L. Thrombocytopenia and Procedural Prophylaxis in the Era of Thrombopoietin Receptor Agonists. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Hum, J.; Jou, J.; Scanlan, R.M.; Shatzel, J. Transfusion strategies in patients with cirrhosis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 104, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigekawa, Y.; Uchiyama, K.; Takifuji, K.; Ueno, M.; Hama, T.; Hayami, S.; Tamai, H.; Ichinose, M.; Yamaue, H. A laparoscopic splenectomy allows the induction of antiviral therapy for patients with cirrhosis associated with hepatitis C virus. Am. Surg. 2011, 77, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S.; Hidemura, R. Surgical Treatment of Portal Hypertension: With Special Reference to the Feature of Intrahepatic Circulatory Disturbances. Jpn. Circ. J. 1964, 28, 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassn, A.M.F.; Al-Fallouji, M.A.; Ouf, T.I.; Saad, R. Portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy. Br. J. Surg. 2000, 87, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.A.; El Gendy, M.M.; Dawoud, I.E.; Shoma, A.; Negm, A.M.; Amer, T.A. Partial Splenic Embolization Versus Splenectomy for the Management of Hypersplenism in Cirrhotic Patients. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 1702–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangireddy, V.G.; Kanneganti, P.C.; Sridhar, S.; Talla, S.; Coleman, T. Management of thrombocytopenia in advanced liver disease. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 28, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ma, K.; He, Z.; Dong, J.; Hua, X.; Huang, X.; Qiao, L. Radiofrequency Ablation for Hypersplenism in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis: A Pilot Study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2005, 9, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, T.D.; Haskal, Z.J. The Role of Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt (Tips) in the Management of Portal Hypertension: Update 2009. Hepatology 2010, 51, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, H. Update on thrombopoietin in preclinical and clinical trials. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 1998, 5, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrault, N.; Chen, Y.C.; Izumi, N.; Kayali, Z.; Mitrut, P.; Tak, W.Y.; Allen, L.F.; Hassanein, T. Avatrombopag Before Procedures Reduces Need for Platelet Transfusion in Patients with Chronic Liver Disease and Thrombocytopenia. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidaka, H.; Kurosaki, M.; Tanaka, H.; Kudo, M.; Abiru, S.; Igura, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Seike, M.; Katsube, T.; Ochiai, T.; et al. Lusutrombopag Reduces Need for Platelet Transfusion in Patients with Thrombocytopenia Undergoing Invasive Procedures. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, H.; Kurosaki, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Itakura, J.; Tsuchiya, K.; Yasui, Y.; Tamaki, N.; Takaura, K.; Komiyama, Y.; et al. Real-life experience of lusutrombopag for cirrhotic patients with low platelet counts being prepared for invasive procedures. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Tateishi, R.; Hiroi, S.; Hongo, Y.; Fujiwara, M.; Kitanishi, Y.; Iwasaki, K.; Takeshima, T.; Igarashi, A. Effects of Lusutrombopag on Post-invasive Procedural Bleeding in Thrombocytopenic Patients with Chronic Liver Disease. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuter, D.J.; Begley, C.G. Recombinant human thrombopoietin: Basic biology and evaluation of clinical studies. Blood 2002, 100, 3457–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, C.; Xia, Y.; Bertino, A.; Glaspy, J.; Roberts, M.; Kuter, D.J. Thrombocytopenia caused by the development of antibodies to thrombopoietin. Blood 2001, 98, 3241–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetri, G.D. Targeted Approaches for the Treatment of Thrombocytopenia. Oncologist 2001, 6, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajiri, K.; Okada, K.; Ito, H.; Kawai, K.; Kashii, Y.; Tokimitsu, Y.; Muraishi, N.; Murayama, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Minemura, M.; et al. Long term changes in thrombocytopenia and leucopenia after HCV eradication with direct-acting antivirals. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Complication | Typical Timing | Pathophysiology | Shared RF with Pre-LT Cirrhosis | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) | Early (≤30 days) or late | Thrombosis at the anastomosis or due to endothelial injury; impaired arterial inflow to the graft and biliary tree | Hypercoagulable state, endothelial dysfunction, previous thrombosis, technical factors | Graft ischemia, biliary necrosis, graft loss, sepsis |

| Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) | Early or late | Thrombosis of the portal inflow due to sluggish flow, intimal injury, hypercoagulability | Portal hypertension, reduced portal flow, inherited/acquired thrombophilia | Impaired graft perfusion, portal hypertension, ascites |

| Hepatic vein thrombosis (HVT) | Early or late | Thrombosis or stenosis of hepatic venous outflow or anastomosis | Hypercoagulability, venous stasis, endothelial injury | Graft congestion, hepatomegaly, ascites, liver failure |

| Inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis or thrombosis | Early or late | Anastomotic narrowing, compression | Venous stasis, surgical technical factors | Lower extremity edema, graft congestion |

| DOAC | Metabolism | Interaction Risk with IS | Preferred Use After LT | Clinical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran [84] | Prodrug, substrate of P-gp only | Strongly affected by Cys, increased exposure with Tac | Avoid in the early and unstable post-LT period | High risk of bleeding due to elevated plasma levels; avoid with CNIs or mTOR inhibitors |

| Rivaroxaban [85,86] | Metabolized via CYP3A4 (60%) and P-gp | Exposure increases with Tac and Cys | Use with caution in stable LT recipients | Monitor for bleeding; adjust dose or avoid concurrent strong CYP3A4/P-gp inhibitors |

| Apixaban [85,86] | Dual elimination via CYP3A4 (~25%) and P-gp | Least affected by CNIs; mild increase with Tac | Preferred DOAC in stable LT patients | Lower interaction potential; suitable for patients with preserved hepatic and renal function |

| Edoxaban [84] | Minimal CYP metabolism; P-gp substrate | Possible accumulation with Cys | Consider only with careful monitoring | Limited data post-LT; avoid with potent P-gp inhibitors |

| Warfarin [88] | CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP3A4 | Multiple interactions but easily monitored via INR | Alternative during the early post-LT phase | Safe when close INR monitoring is feasible; unaffected by P-gp inhibition |

| Factor Concentrates or Blood Products | Current Recommendations (A) | Special Notice (A) | Current Recommendations (B) | Special Notice (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K | Not supported | No improvement of INR in liver cirrhosis [105,106] Not evaluated in the prevention of spontaneous bleeding | Not supported | No improvement of INR in liver cirrhosis [105,106] No reduction in rebleeding within 30 days in patients with cirrhosis and UGIB [107] |

| FFP transfusions | Not supported | Potential transfusion-related circulatory overload, transfusion-related acute lung injury [90,108] | Not supported | Potentially increases mortality, fails to control rebleeding [109] |

| Platelet transfusions | Not supported, controversial (low-grade evidence) | No clear-cut evidence suggesting a role in the prevention of spontaneous bleeding [90,110] | Not supported, controversial (low-grade evidence) | Potentially TEG-guided, no difference in rebleeding and 6-week mortality [111] |

| Cryoprecipitate (fibrinogen, factor VIII, factor XIII, and vWF) | Not supported | No effect on mortality risk or bleeding outcome [112] | Not supported yet, potential role | Benefit in acute bleeding, prevention of rebleeding on day 1–5, and 5-day mortality [113] |

| Thrombopoietin receptor agonists | Not supported | Possible role in the prevention of procedure-related bleeding [114] | Not supported | Possible role in the prevention of procedure-related bleeding [114] |

| Tranexamic acid | Not supported | Proved ineffective in subarachnoid hemorrhage [115] Possible thromboembolic adverse events [116] | Not supported | No benefit shown [116] Possible thromboembolic adverse events [116] |

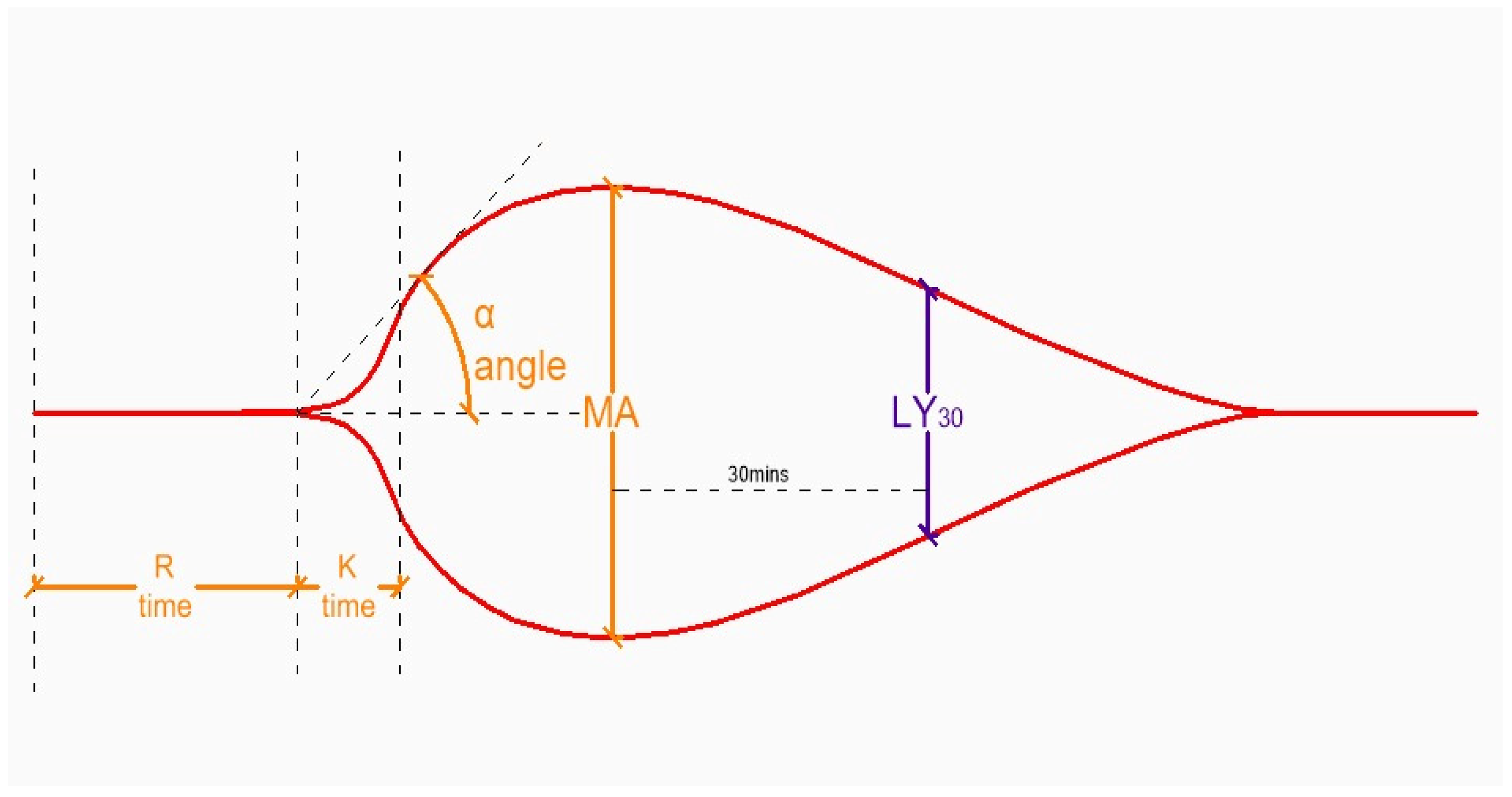

| TEG Parameter (ROTEM) | Aberrancy | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| R (CT) | ↑ | ↓ clotting factors, drugs (heparin, warfarin, NOACs) |

| K (CFT) | ↑ | ↓ fibrinogen ↓ fibrinogen, ↓ clotting factors, drugs |

| A (α) | ↓ | |

| MA (MCF) | ↓ | ↓ platelets, ↓ fibrinogen |

| LY30 (ML) | ↑ | ↑ fibrinolysis |

| Cause | Treatment | Dose (Administration Route) |

|---|---|---|

| Heparin | Protamin sulphate | 1 mg/100 IU heparin |

| Warfarin | Phytomenadion | 0.5–1 mg (po/iv) |

| Apixaban, rivaroxaban | Andexanet α | 480–1760 mg |

| Dabigatran | Idarucizumab | 5 g |

| ↓ Clotting factors | FFP | 10–15 mL/kg (iv) |

| PCC | 25–30 IU/kg (iv) | |

| ↓ Platelets | Platelet transfusion | 1 dose /10 kg BW (iv) |

| Avatrombopag Lusutrombopag | 40–60 mg/day over 5 d (po) 3 mg once daily over 7 d | |

| ↓ Fibrinogen | Cryoprecipitate | 1 U/10 kg BW (iv) |

| Fibrinogen concentrate | 1–2 g (iv) | |

| ↑ Fibrinolysis | Tranexamic acid | 500–1000 mg × 2–4/day (po/iv) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bozic, D.; Babic, A.; Olic, I.; Lalovac, M.; Mijic, M.; Madir, A.; Podrug, K.; Mestrovic, A. Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Cirrhosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Medicina 2026, 62, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010104

Bozic D, Babic A, Olic I, Lalovac M, Mijic M, Madir A, Podrug K, Mestrovic A. Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Cirrhosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleBozic, Dorotea, Ana Babic, Ivna Olic, Milos Lalovac, Maja Mijic, Anita Madir, Kristian Podrug, and Antonio Mestrovic. 2026. "Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Cirrhosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches" Medicina 62, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010104

APA StyleBozic, D., Babic, A., Olic, I., Lalovac, M., Mijic, M., Madir, A., Podrug, K., & Mestrovic, A. (2026). Coagulation Abnormalities in Liver Cirrhosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Medicina, 62(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010104