Outcome of Matrix Rotation Versus Single Incision Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty in Upper Quadrant Breast Carcinomas

Abstract

1. Introduction

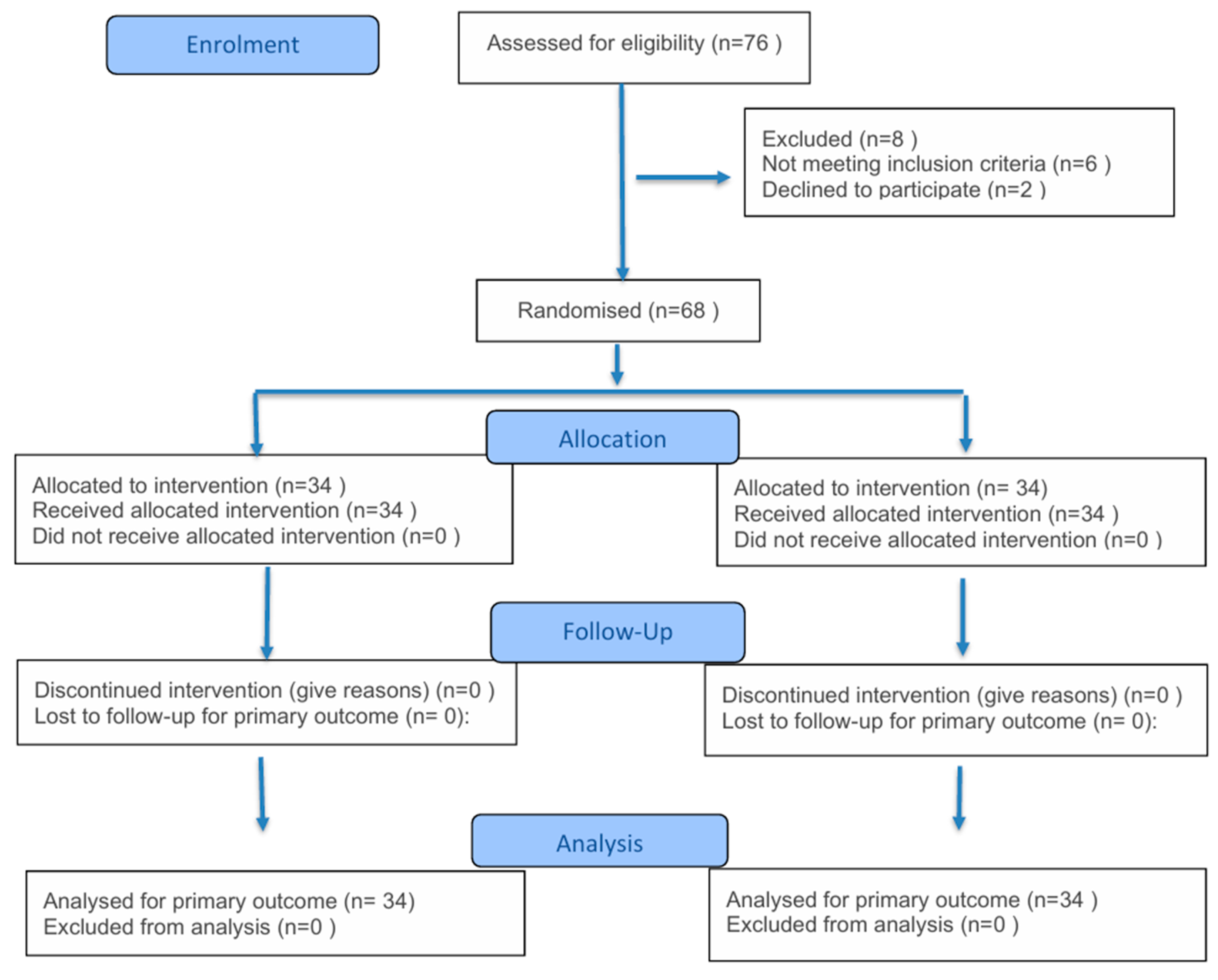

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Surgical Procedure

2.2.1. Preoperative Considerations and Flap Design

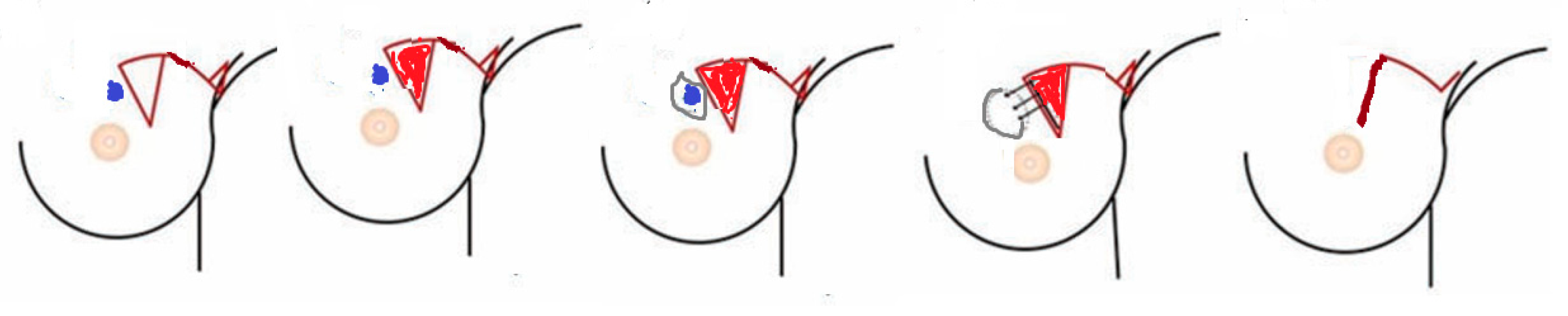

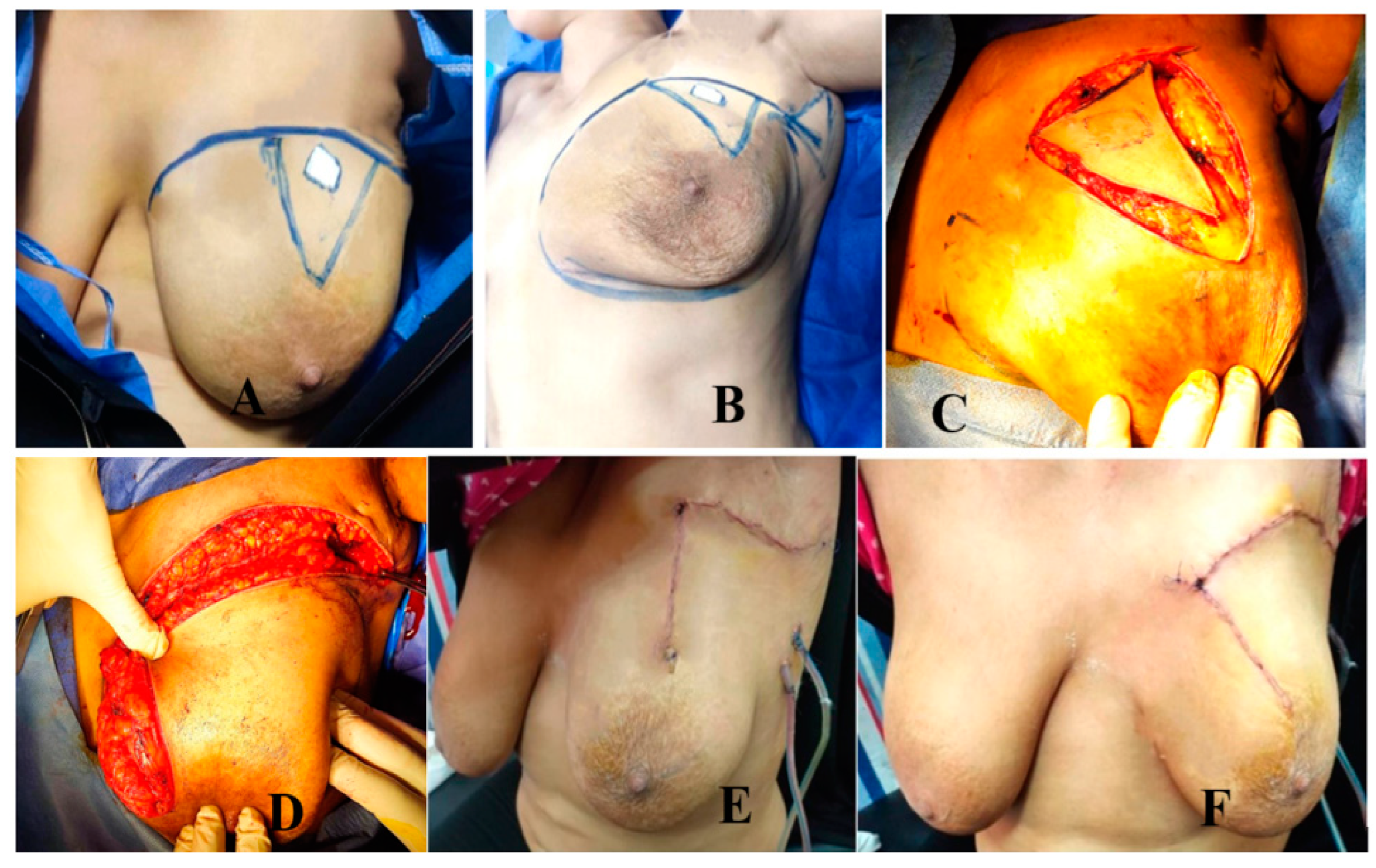

Group A: MRF Group (Figure 2 and Figure 3)

- Operative technique (Figure 3)

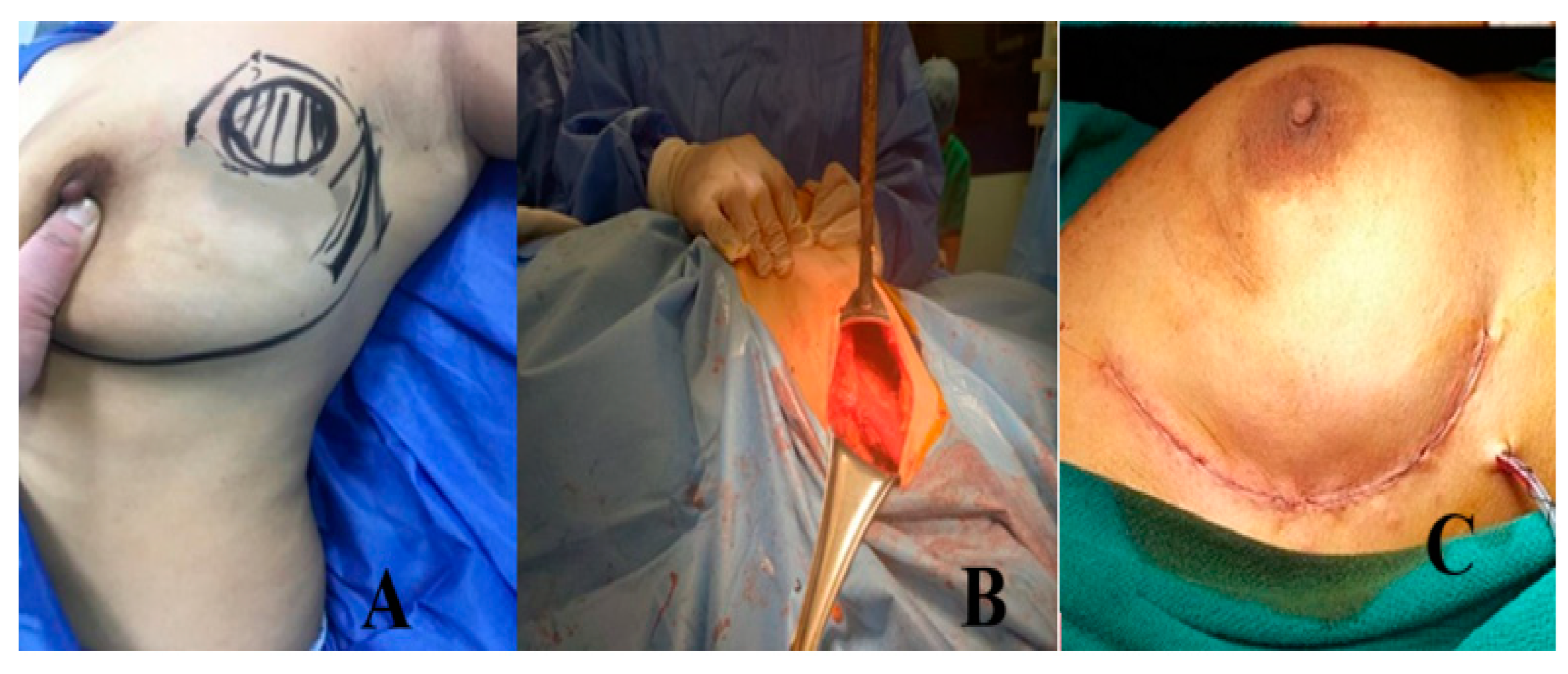

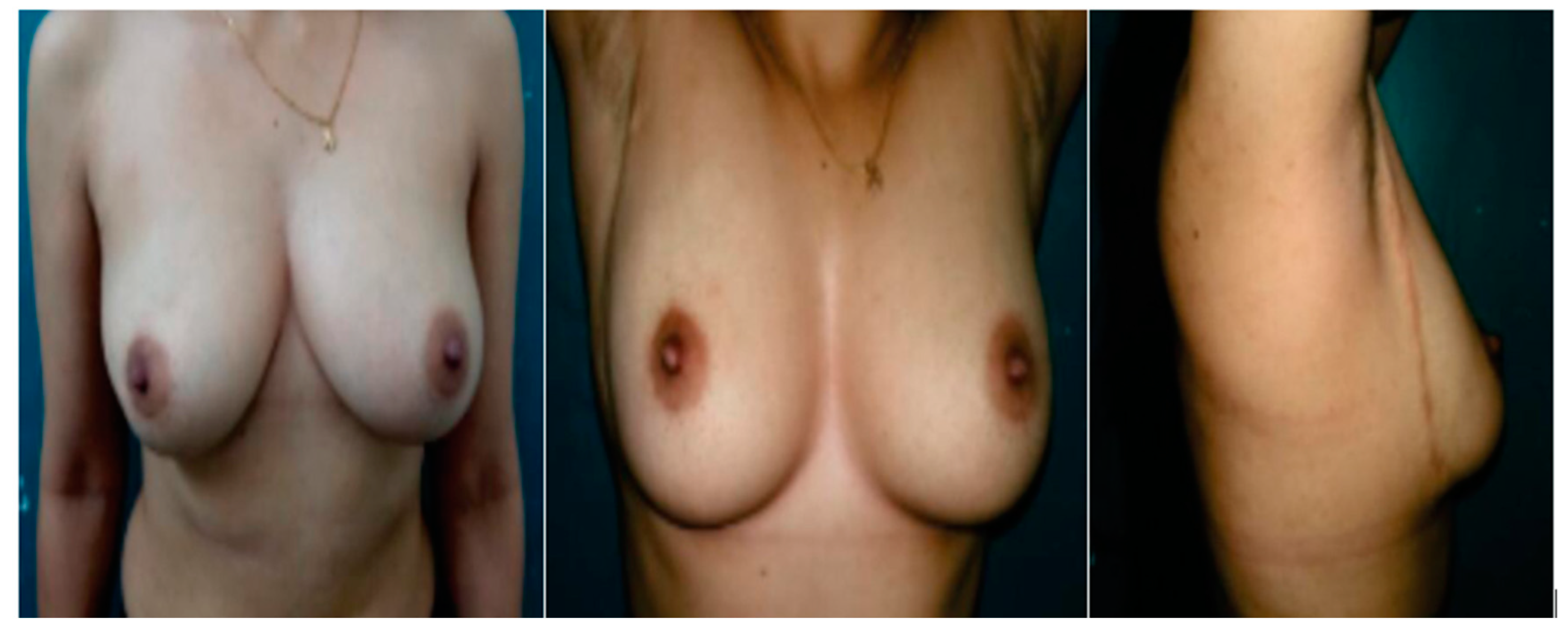

Group B: Lateral Mammoplasty Group (Figure 4 and Figure 5)

- Preoperative planning and marking

2.3. Follow-Up and Outcomes

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; Anderson, S. Conservative surgery for the management of invasive and noninvasive carcinoma of the breast: NSABP trials. National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project. World J. Surg. 1994, 18, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronesi, U.; Zucali, R.; Luini, A. Local control and survival in early breast cancer: The Milan trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1986, 12, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B.; Brown, A.; Mamounas, E.; Wieand, S.; Robidoux, A.; Margolese, R.G.; Cruz, A.B.; Fisher, E.R.; Wickerham, D.L.; Wolmark, N.; et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: Findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouzier, R.; Extra, J.-M.; Carton, M.; Falcou, M.-C.; Vincent-Salomon, A.; Fourquet, A.; Pouillart, P.; Bourstyn, E. Primary chemotherapy for operable breast cancer: Incidence and prognostic significance of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence after breast-conserving surgery. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 3828–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, K.B.; Cuminet, J.; Fitoussi, A.; Nos, C.; Mosseri, V. Cosmetic sequelae after conservative treatment for breast cancer: Classification and results of surgical correction. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1998, 41, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabka, C.J.; Bohmert, H. Future prospects for reconstructive surgery in breast cancer. Semin. Surg. Oncol. 1996, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munhoz, A.M.; Montag, E.; Gemperli, R. Oncoplastic breast surgery: Indications, techniques and perspectives. Gland Surg. 2013, 2, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clough, K.B.; Lewis, J.S.; Couturaud, B.; Fitoussi, A.; Nos, C.; Falcou, M.C. Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast-conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann. Surg. 2003, 237, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulley, S.J.; Durani, P.; Macmillan, R.D. Therapeutic mammaplasty for centrally located breast tumors. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006, 117, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huemer, G.M.; Schrenk, P.; Moser, F.; Wagner, E.; Wayand, W. Oncoplastic techniques allow breast-conserving treatment in centrally located breast cancers. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007, 120, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantürk, N.Z.; Şimşek, T.; Gürdal, S.Ö. Oncoplastic Breast-Conserving Surgery According to Tumor Location. Eur. J. Breast Health 2021, 17, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staub, G.; Fitoussi, A.; Falcou, M.C.; Salmon, R.J. Résultats carcinologiques et esthétiques du traitement du cancer du sein par plastie mammaire. 298 cas [Breast cancer surgery: Use of mammaplasty. Results. Series of 298 cases]. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2008, 53, 124–134. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrino, P.; Campora, E.; Santi, P. Postquadrantectomy breast deformities: Classification and techniques of surgical correction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1987, 79, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, K.; Jayarajah, U.; De Silva, A. Aesthetic and surgical outcomes of the modified matrix rotation technique for upper inner quadrant breast tumors: A case series. J. Int. Med. Res. 2024, 52, 3000605241239852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abdelrahman, E.M.; Shoulah, A.A.; Ghazal, S.O.; Nchoukat, M.K.; Balbaa, M.A. Cheek advancement flap for nasal reconstruction following surgical excision of basal cell carcinoma: Early outcome and patient satisfaction. Egypt. J. Surg. 2021, 40, 322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, J.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, E.J.; Park, K. Values of a patient and observer scar assessment scale to evaluate the facial skin graft scar. Ann. Dermatol. 2016, 28, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, V.; Hawaldar, R.; Badwe, R.A. Safety of partial breast reconstruction in extended indications for conservative surgery in breast cancer. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2010, 1, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, J.; Chen, D.R.; Wang, Y.F.; Lai, H.W. Oncoplastic Surgery for Upper/Upper Inner Quadrant Breast Cancer. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.S.; Chen, Y.-H.; Gadd, M.A.; Gelman, R.; Lester, S.C.; Schnitt, S.J.; Sgroi, D.C.; Silver, B.J.; Smith, B.L.; Troyan, S.L.; et al. Eight-year update of a prospective study of wide excision alone for small low- or intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 143, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szynglarewicz, B.; Maciejczyk, A.; Forgacz, J.; Matkowski, R. Breast segmentectomy with rotation mammoplasty as an oncoplastic approach to extensive ductal carcinoma in situ. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2016, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leclerc, A.F.; Jerusalem, G.; Devos, M.; Crielaard, J.M.; Maquet, D. Multidisciplinary management of breast cancer. Arch. Public Health 2016, 74, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filip, A.C.; Marcu, O.A.; Pop, M.S.; Debucean, D. The multidisciplinary approach to breast cancer—The role of support specialties before and after mastectomy. Arch. Balk. Med. Union 2020, 55, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabi, A.; Rossi, A.; Mocini, E.; Cardinali, L.; Bonavolontà, V.; Cenci, C.; Magno, S.; Barberi, V.; Moretti, A.; Besharat, Z.M.; et al. An Integrated Care Approach to Improve Wellbeing in Breast Cancer Patients. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre-Montero, J.C.; Casla-Barrio, S.; Herrero-López, B.; García-Saénz, J.Á. Editorial: Exercise, physical therapy, and wellbeing in breast cancer patients. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1118718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvet, L.; Thune, I.; Elvsaas, I.K.Ø.; Fors, E.; Lundgren, S.; Bertheussen, G.; Leivseth, G.; Oldervoll, L. The effect of exercise on fatigue and physical functioning in breast cancer patients during and after treatment and at 6 months follow-up: A meta-analysis. Breast 2017, 33, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letzkus, J.; Río, M.J.; del Rencoret, C.; Belmar, A.; Ivanova, G.; Hidalgo, D.; Gamboa, J. Burow’s triangle advancementflap: A reliabletool on oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery. Mastology 2021, 31, e20200087. [Google Scholar]

- Alkelany, A.; Hagag, M.; Bakr, F.; Abdella, A.; Eldesouky, M. Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty as an Oncoplastic Technique in the Management of Laterally Located Breast Cancer. Menoufia Med. J. 2024, 37, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fayed, M.; Sharaan, M.; Gebaly, A.; Asal, F. Oncoplastic surgery for laterally located breast cancer: A new approach. Clin. Surg. 2020, 5, 2790. [Google Scholar]

- van Paridon, M.W.; Kamali, P.; Paul, M.A.; Wu, W.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Kansal, K.J.; Houlihan, M.J.; Morris, D.J.; Lee, B.T.; Lin, S.J.; et al. Oncoplastic breast surgery: Achieving oncological and aesthetic outcomes. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 116, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Kohli, P.S.; Bagaria, D. Lateral oncoplastic breast surgery (LOBS) e a new surgical technique and short term results. Am. J. Surg. 2018, 216, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaviani, A.; Sodagari, N.; Sheikhbahaei, S.; Eslami, V.; Hafezi-Nejad, N.; Safavi, A.; Noparast, M.; Fitoussi, A. From radical mastectomy to breast-conserving therapy and oncoplastic breast surgery: A narrative review comparing oncological result, cosmetic outcome, quality of life, and health economy. ISRN Oncol. 2013, 2013, 742462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, E.J.D.; Gouveia, P.F.; Nos, C.; Poulet, B.; Sarfati, I.; Clough, K.B. A new level 1 oncoplastic technique for breast conserving surgery: Rotation glandular flap. Breast 2013, 22, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, A.; Elsisi, A.; Rageh, T.; Shahin, M. Modified Inferior Based Reduction Mammoplasty Versus Matrix Rotational Flap in Upper Inner Quadrant Breast Cancer. Menoufia Med. J. 2023, 36, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, M.; Rizk, M.; Fouad, H.; Mostafa, T.Y. Therapeutic mammoplasty: Is it a solution for treatment of early breast cancer? Egypt. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 45, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draaijers, L.J.; Tempelman, F.R.; Botman, Y.A.; Tuinebreijer, W.E.; Middelkoop, E.; Kreis, R.W.; van Zuijlen, P. The Patient and Observer Scar Assessment Scale: A Reliable and Feasible Tool for Scar Evaluation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004, 113, 1960–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitoussi, A.D.; Berry, M.G.; Famà, F.; Falcou, M.C.; Curnier, A.; Couturaud, B.; Reyal, F.; Salmon, R.J. Oncoplastic breast surgery for cancer: Analysis of 540 consecutive cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010, 125, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haloua, M.H.; Krekel, N.M.; Winters, H.A.; Rietveld, D.H.; Meijer, S.; Bloemers, F.W.; Tol, M.P.v.D. A systematic review of oncoplastic breast-conserving surgery: Current weaknesses and future prospects. Ann. Surg. 2013, 257, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, E.M.; Nawar, A.M.; Balbaa, M.A.; Shoulah, A.A.; Shora, A.A.; Kharoub, M.S. Oncoplastic Volume Replacement for Breast Cancer: Latissimus Dorsi Flap versus Thoracodorsal Artery Perforator Flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, E.; Khater, A.; Atef, A.; Hosam, A. Oncologic and Aesthetic Outcomes of Matrix Rotation Mammoplasty in Management of Upper Inner Quadrant Breast Cancer: A Single Centre Experience. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 16, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group A Matrix Rotation n = 34 | Group B SLIM n = 34 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 51.4 ± 9.4 | 52.6 ± 8.1 | 0.575 |

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 29.8 ± 3.11 | 28.3 ± 4.2 | 0.99 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Smoking | n (%) | 6 (17.7%) | 7 (20.6%) | 0.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | n (%) | 4 (11.8%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0.82 |

| Hypertension | n (%) | 4 (11.8%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0.85 |

| Ischemic heart disease | n (%) | 2 (5.9%) | 2 (5.9%) | 1.00 |

| Tumor Characteristics | ||||

| Tumor Size | ||||

| T1 | n (%) | 7 (20.6%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0.752 |

| T2 | n (%) | 21 (61.7%) | 23(67.6%) | 0.8 |

| T3 | n (%) | 6 (17.7%) | 6 (17.7%) | 1.00 |

| Variable | Group A MRF (n = 34) | Group B SLIM (n = 34) | p Value | Mean Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (Min) | Mean ± SD | 124.6 ± 23.2 | 106.3 ± 17.3 | <0.001 * | 18.3 (8.39–28.21) |

| Hospital stay (Days) | Mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.89 | 2.3 ± 0.76 | 0.051 | 0.4 (0.0007–0.8) |

| Mean postoperative follow-up (Months) | Mean ± SD | 13.2 ± 2.4 | 13.6 ± 3.1 | 0.554 | 0.4 (−1.47–0.94) |

| Safety margin | n (%) | 1.00 | ---- | ||

| Positive | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Negative | 34 (100%) | 34 (100%) |

| Postoperative Complications | Group A MRF (n = 34) | Group B SLIM (n = 34) | p Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematoma | n (%) | 5 (14.7%) | 2 (5.9%) | <0.001 * | 2.759 (0.51–14.5) |

| Seroma | n (%) | 4 (11.8%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.014 * | 2.133 (0.46–11.73) |

| Wound infection | n (%) | 4 (11.8%) | 1 (2.95%) | <0.001 * | 4.4 (0.65–55.23) |

| Marginal skin necrosis | n (%) | 1 (2.95%) | 1 (2.95%) | 1.00 | 1.0 (0.05–19.52) |

| NAC necrosis | n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | ---- |

| Impaired NAC sensation | n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | ---- |

| Fat necrosis | n (%) | 4 (11.8%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.014 * | 2.133 (0.46–11.73) |

| Areola deviation | n (%) | 5 (14.7%) | 1 (2.95%) | <0.001 * | 5.69 (0.68–68.76) |

| Asymmetry | n (%) | 7 (20.6%) | 8 (23.5%) | 0.072 | 0.843 (0.28–2.45) |

| Local recurrence | n (%) | 1 (2.95%) | 1 (2.95%) | 1.00 | 1.0 (0.05–19.52) |

| Time of recurrence (months) | Mean | 11 | 13. | 0.083 | |

| Distant metastasis | n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ---- |

| Variable | Group A MRF (n = 34) | Group B SLIM (n = 34) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likert Scale | ||||

| Excellent | n (%) | 11 (32.4%) | 17 (50%) | <0.001 * |

| Good | n (%) | 13 (38.2%) | 14 (41.2%) | 0.9 |

| Fair | n (%) | 9 (26.5%) | 3 (8.8%) | <0.001 * |

| Poor | n (%) | 1 (2.95%) | 0 (0%) | 0.92 |

| Bad | n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 |

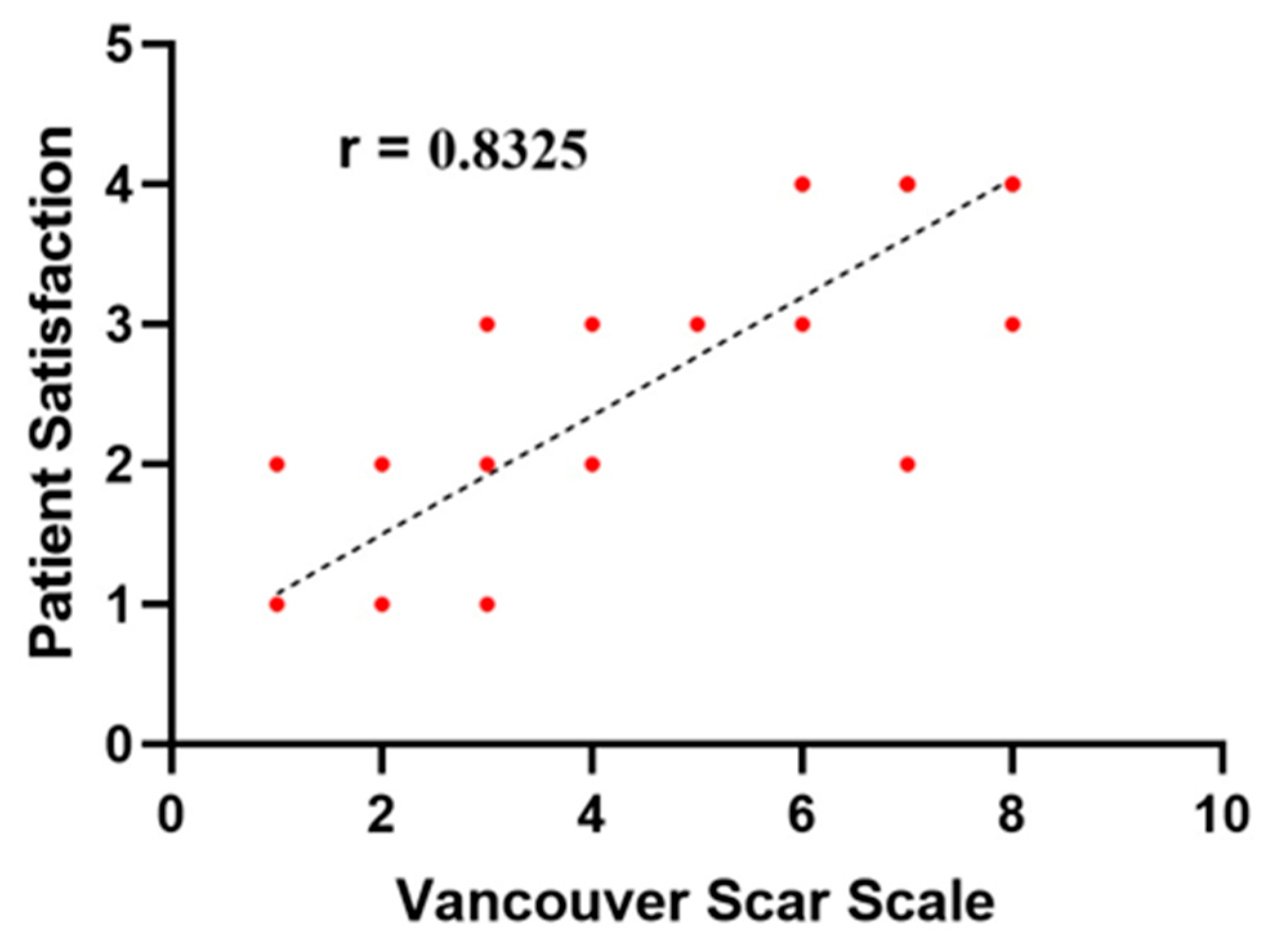

| Vancouver Scar Scale | Median (IQR) | 3.5 (4) | 2.5 (2) | <0.001 * |

| Vancouver Scar Components’ Score | ||||

| Vascularity | Mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.34 | 0.55 ± 0.13 | 0.01 * |

| Pigmentation | Mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 0.26 | 1.1 ± 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Pliability | Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 0.32 | 0.7 ± 0.12 | 0.001 * |

| Height (mm) | Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.22 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdelrahman, E.M.; Mohsen, S.M.; Mohamed, A.G.; Abdeen, M.S.; Elsayed, M.A.; Ibrahim, Z.M.; Abdelraouf, O.R.; Hegazy, H.; Abdelhalim, M.G. Outcome of Matrix Rotation Versus Single Incision Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty in Upper Quadrant Breast Carcinomas. Medicina 2025, 61, 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091609

Abdelrahman EM, Mohsen SM, Mohamed AG, Abdeen MS, Elsayed MA, Ibrahim ZM, Abdelraouf OR, Hegazy H, Abdelhalim MG. Outcome of Matrix Rotation Versus Single Incision Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty in Upper Quadrant Breast Carcinomas. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091609

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelrahman, Emad M., Sherif M. Mohsen, Amr G. Mohamed, Mostafa S. Abdeen, Mohamed A. Elsayed, Zizi M. Ibrahim, Osama R. Abdelraouf, Hassan Hegazy, and Mahmoud G. Abdelhalim. 2025. "Outcome of Matrix Rotation Versus Single Incision Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty in Upper Quadrant Breast Carcinomas" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091609

APA StyleAbdelrahman, E. M., Mohsen, S. M., Mohamed, A. G., Abdeen, M. S., Elsayed, M. A., Ibrahim, Z. M., Abdelraouf, O. R., Hegazy, H., & Abdelhalim, M. G. (2025). Outcome of Matrix Rotation Versus Single Incision Lateral Sulcus Mammoplasty in Upper Quadrant Breast Carcinomas. Medicina, 61(9), 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091609