Current Perspectives on Remifentanil-PCA for Labor Analgesia: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Analgesic Efficacy of Remifentanil-PCA Compared to Other Labor Pain Relief Options

2.4. Parturient Satisfaction

2.5. Maternal Side Effects and Potential Complications

2.6. Safety Concerns

2.7. Association with the Progress of Labor and Neonatal Outcomes

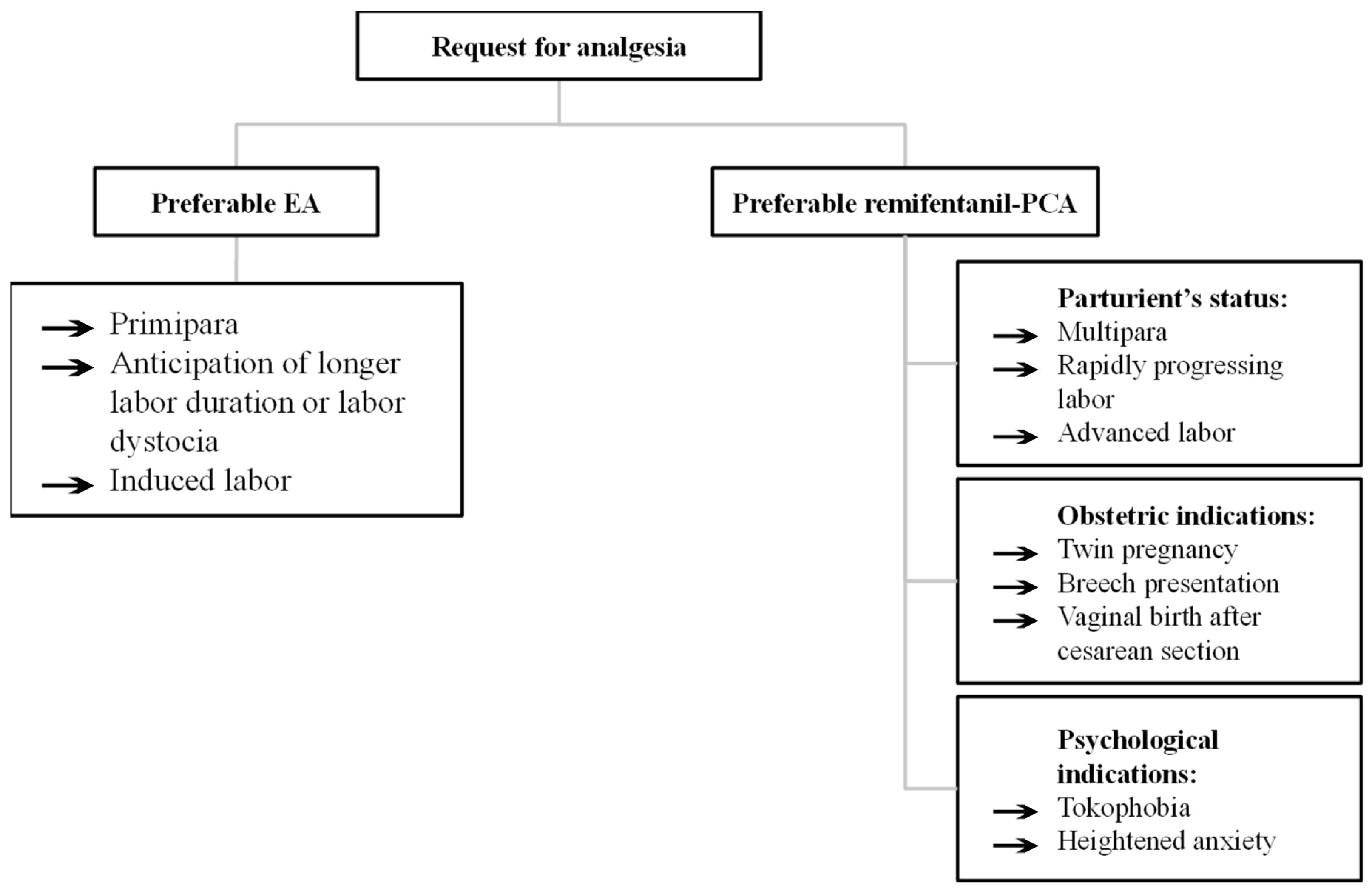

2.8. Obstetric Considerations

2.9. Off-Label Use and Informed Consent

2.10. Limitations of Reviewed Evidence

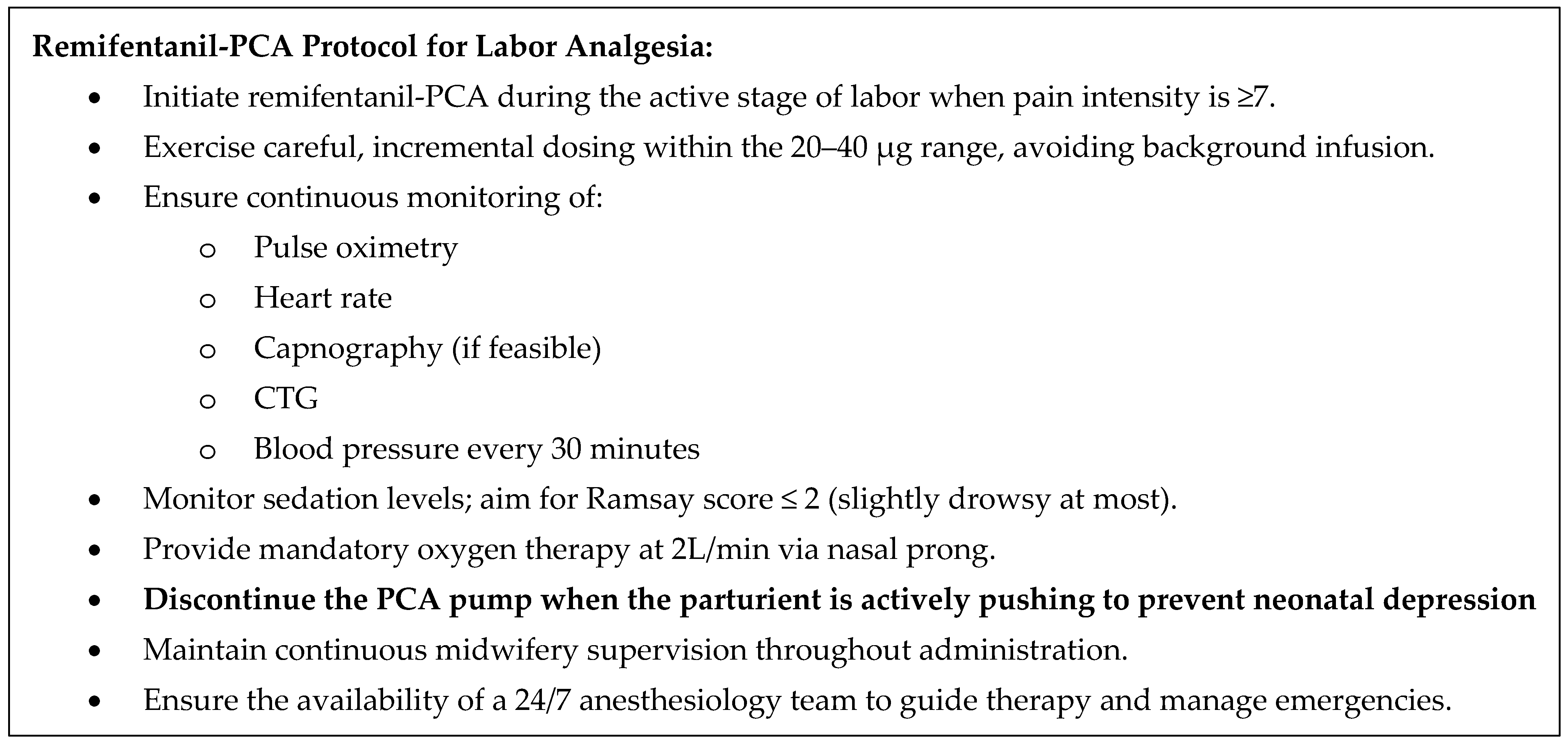

2.11. Our Experience

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lowe, N.K. The nature of labor pain. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, L.; Nelson, S.M.; Kearns, R.J. Epidural analgesia in labor: A narrative review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuarez-Easton, S.; Erez, O.; Zafran, N.; Carmeli, J.; Garmi, G.; Salim, R. Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S1246–S1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Pegrum, A.; Stacey, R.G. Patient-controlled analgesia using remifentanil in the parturient with thrombocytopaenia. Anaesthesia 1999, 54, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlow, J.A.; Waterhouse, P. Patient-controlled analgesia in labour using remifentanil in two parturients with platelet abnormalities. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 411–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.M.; Hill, D.A.; Fee, J.P. Patient-controlled analgesia for labour using remifentanil: A feasibility study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2001, 87, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronel, I.; Weiniger, C.F. Non-regional analgesia for labour: Remifentanil in obstetrics. BJA Educ. 2019, 19, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Velde, M.; Carvalho, B. Remifentanil for labor analgesia: An evidence-based narrative review. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2016, 25, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintaric, T.S. B20 Non-neuraxial labour analgesia. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2024, 49, A350–A353. [Google Scholar]

- Blajic, I.; Zagar, T.; Semrl, N.; Umek, N.; Lucovnik, M.; Stopar Pintaric, T. Analgesic efficacy of remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia versus combined spinal-epidural technique in multiparous women during labour. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markova, L.; Lucovnik, M.; Verdenik, I.; Stopar Pintarič, T. Delivery mode and neonatal morbidity after remifentanil-PCA or epidural analgesia using the Ten Groups Classification System: A 5-year single-centre analysis of more than 10,000 deliveries. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 277, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucovnik, M.; Verdenik, I.; Stopar Pintaric, T. Intrapartum Cesarean Section and Perinatal Outcomes after Epidural Analgesia or Remifentanil-PCA in Breech and Twin Deliveries. Medicina 2023, 59, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopar Pintarič, T.; Pavlica, M.; Druškovič, M.; Kavšek, G.; Verdenik, I.; Pečlin, P. Relationship between labour analgesia modalities and types of anaesthetic techniques in categories 2 and 3 intrapartum caesarean deliveries. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 24, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopar Pintaric, T.; Vehar, L.; Sia, A.T.; Mirkovic, T.; Lucovnik, M. Remifentanil Patient-Controlled Analgesia for Labor Analgesia at Different Cervical Dilations: A Single Center Retrospective Analysis of 1045 Cases. Medicina 2025, 61, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stourac, P.; Kosinova, M.; Harazim, H.; Huser, M.; Janku, P.; Littnerova, S.; Jarkovsky, J. The analgesic efficacy of remifentanil for labour. Systematic review of the recent literature. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc Czech Repub. 2016, 160, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmanen, P.; Sarvela, J.; Akural, E.I.; Raudaskoski, T.; Korttila, K.; Alahuhta, S. Intravenous remifentanil vs. epidural levobupivacaine with fentanyl for pain relief in early labour: A randomised, controlled, double-blinded study. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2008, 52, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evron, S.; Glezerman, M.; Sadan, O.; Boaz, M.; Ezri, T. Remifentanil: A novel systemic analgesic for labor pain. Anesth. Analg. 2005, 100, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.J.A.; MacArthur, C.; Hewitt, C.A.; Handley, K.; Gao, F.; Beeson, L.; Daniels, J. Intravenous remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia versus intramuscular pethidine for pain relief in labour (RESPITE): An open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, A.; Hahn, N.; Broscheit, J.; Muellenbach, R.M.; Rieger, L.; Roewer, N.; Kranke, P. Remifentanil for labour analgesia: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2012, 29, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Zhu, F.; Moodie, J.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, D.; Martin, J. Remifentanil as an alternative to epidural analgesia for vaginal delivery: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Clin. Anesth. 2017, 39, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Q.; Chen, X.B.; Li, H.B.; Qiu, M.T.; Duan, T. A comparison of remifentanil parturient-controlled intravenous analgesia with epidural analgesia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volmanen, P.; Akural, E.; Raudaskoski, T.; Ohtonen, P.; Alahuhta, S. Comparison of remifentanil and nitrous oxide in labour analgesia. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2005, 49, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, M.R.; Verwey, R.A.; Kam-Endtz, C.E.; van der Linden, P.D.; Stienstra, R. Obstetric analgesia: A comparison of patient-controlled meperidine, remifentanil, and fentanyl in labour. Br. J. Anaesth. 2010, 104, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.L.; Sng, B.L.; Sia, A.T. A comparison between remifentanil and meperidine for labor analgesia: A systematic review. Anesth. Analg. 2011, 113, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.K.; Cheng, B.C.; Chan, W.S.; Lam, K.K.; Chan, M.T. A double-blind randomised comparison of intravenous patient-controlled remifentanil with intramuscular pethidine for labour analgesia. Anaesthesia 2011, 66, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.M.; Dobson, G.T.; Hill, D.A.; McCracken, G.R.; Fee, J.P.H. Patient controlled analgesia for labour: A comparison of remifentanil with pethidine*. Anaesthesia 2005, 60, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volikas, I.; Male, D. A comparison of pethidine and remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia in labour. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2001, 10, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stourac, P.; Suchomelova, H.; Stodulkova, M.; Huser, M.; Krikava, I.; Janku, P.; Haklova, O.; Hakl, L.; Stoudek, R.; Gal, R.; et al. Comparison of parturient—Controlled remifentanil with epidural bupivacain and sufentanil for labour analgesia: Randomised controlled trial. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc Czech Repub. 2014, 158, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocki, D.; Matot, I.; Einav, S.; Eventov-Friedman, S.; Ginosar, Y.; Weiniger, C.F. A randomized controlled trial of the efficacy and respiratory effects of patient-controlled intravenous remifentanil analgesia and patient-controlled epidural analgesia in laboring women. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 118, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logtenberg, S.; Oude Rengerink, K.; Verhoeven, C.J.; Freeman, L.M.; van den Akker, E.; Godfried, M.B.; van Beek, E.; Borchert, O.; Schuitemaker, N.; van Woerkens, E.; et al. Labour pain with remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia versus epidural analgesia: A randomised equivalence trial. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 124, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnet, M.-P.; Prunet, C.; Baillard, C.; Kpéa, L.; Blondel, B.; Le Ray, C. Anesthetic and Obstetrical Factors Associated with the Effectiveness of Epidural Analgesia for Labor Pain Relief: An Observational Population-Based Study. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2017, 42, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agaram, R.; Douglas, M.J.; McTaggart, R.A.; Gunka, V. Inadequate pain relief with labor epidurals: A multivariate analysis of associated factors. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2009, 18, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, M.A. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S110–S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, W.; Ip, W.Y.; Chan, D. Maternal anxiety and feelings of control during labour: A study of Chinese first-time pregnant women. Midwifery 2007, 23, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, V.H.; Thomson, G.; Cook, J.; Storey, H.; Beeson, L.; MacArthur, C.; Wilson, M. Qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of intramuscular pethidine or remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia for labour pain. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, T.O.; Seiler, S.; Halvorsen, A.; Rosland, J.H. Labour analgesia: A randomised, controlled trial comparing intravenous remifentanil and epidural analgesia with ropivacaine and fentanyl. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2012, 29, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douma, M.R.; Middeldorp, J.M.; Verwey, R.A.; Dahan, A.; Stienstra, R. A randomised comparison of intravenous remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia with epidural ropivacaine/sufentanil during labour. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2011, 20, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.T.; Hassanin, M.Z. Neuraxial analgesia versus intravenous remifentanil for pain relief in early labor in nulliparous women. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 286, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcioglu, O.; Akin, S.; Demir, S.; Aribogan, A. Patient-controlled intravenous analgesia with remifentanil in nulliparous subjects in labor. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2007, 8, 3089–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balki, M.; Kasodekar, S.; Mbbs, S.D.; Bernstein, P.; Carvalho, J.C. Remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia for labour: Optimizing drug delivery regimens. Can. J. Anaesth. 2007, 54, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.M.; Bloemenkamp, K.W.; Franssen, M.T.; Papatsonis, D.N.; Hajenius, P.J.; Hollmann, M.W.; Woiski, M.D.; Porath, M.; van den Berg, H.J.; van Beek, E.; et al. Patient controlled analgesia with remifentanil versus epidural analgesia in labour: Randomised multicentre equivalence trial. BMJ 2015, 23, h846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurlow, J.A.; Laxton, C.H.; Dick, A.; Waterhouse, P.; Sherman, L.; Goodman, N.W. Remifentanil by patient-controlled analgesia compared with intramuscular meperidine for pain relief in labour. Br. J. Anaesth. 2002, 88, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodnett, E.D. Pain and women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: A systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, S160–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, L.Y.; Jones, L.E.; Davey, M.A.; McDonald, S. The nature of labour pain: An updated review of the literature. Women Birth 2019, 32, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Paech, M.J.; McDonald, S.J.; Evans, S.F. Maternal satisfaction with childbirth and intrapartum analgesia in nulliparous labour. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2003, 43, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messmer, A.A.; Potts, J.M.; Orlikowski, C.E. A prospective observational study of maternal oxygenation during remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia use in labour. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, P.N.; Colquhoun, A.D.; Hanning, C.D. Maternal oxygenation during normal labour. Br. J. Anaesth. 1989, 62, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.P.; Reynolds, F. Maternal hypoxaemia during labour and delivery: The influence of analgesia and effect on neonatal outcome. Anaesthesia 1995, 50, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinney, M.A.; Rose, C.H.; Traynor, K.D.; Deutsch, E.; Memon, H.U.; Tanouye, S.; Arendt, K.W.; Hebl, J.R. Emergency bedside cesarean delivery: Lessons learned in teamwork and patient safety. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, R.; Hyams, J.; Bythell, V. Cardiac arrest in an obstetric patient using remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia. Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melber, A.A. Remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) in labour-in the eye of the storm. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logtenberg, S.L.M.; Vink, M.L.; Godfried, M.B.; Beenakkers, I.C.M.; Schellevis, F.G.; Mol, B.W.; Verhoeven, C.J. Serious adverse events attributed to remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia during labour in The Netherlands. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2019, 39, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.L.; Sng, B.L.; Zhang, Q.; Han, N.L.R.; Sultana, R.; Sia, A.T.H. A case series of vital signs-controlled, patient-assisted intravenous analgesia (VPIA) using remifentanil for labour and delivery. Anaesthesia 2017, 72, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, A.; Aubelle, M.S.; Chollat, C. Fetal, Preterm, and Term Neonate Exposure to Remifentanil: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Paediatr. Drugs 2023, 25, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- e Silva, Y.P.; Gomez, R.S.; Marcatto Jde, O.; Maximo, T.A.; Barbosa, R.F.; e Silva, A.C. Early awakening and extubation with remifentanil in ventilated premature neonates. Pediatr. Anesth. 2008, 18, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorbiörnson, A.; da Silva Charvalho, P.; Gupta, A.; Stjernholm, Y.V. Duration of labor, delivery mode and maternal and neonatal morbidity after remifentanil patient-controlled analgesia compared with epidural analgesia. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2020, 6, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadha, Y.C.; Mahmood, T.A.; Dick, M.J.; Smith, N.C.; Campbell, D.M.; Templeton, A. Breech Delivery and Epidural Analgesia. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1992, 99, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parissenti, T.K.; Hebisch, G.; Sell, W.; Staedele, P.E.; Viereck, V.; Fehr, M.K. Risk factors for emergency caesarean section in planned vaginal breech delivery. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2017, 295, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobman, W.A.; Dooley, S.L.; Peaceman, A.M. Risk Factors for Cesarean Delivery in Twin Gestations near Term. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 92, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaschevatzky, O.E.; Shalit, A.; Levy, Y.; Günstein, S. Epidural Analgesia during Labour in Twin Pregnancy. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1977, 84, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruikshank, D.P. Intrapartum Management of Twin Gestations. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Remifentanil-PCA Dose | Comparator | Result—Analgesic Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Douma et al., 2010, N = 180 [23] | LD: 40 µg + B 40 µg LO: 2 min | Pethidine IV LD 49.5 mg + B 5 mg LO 10 min Fentanyl IV LD 50 µg + B 20 µg LO 5 min | Remifentanil provided superior analgesia to pethidine and fentanyl during the 1st hour |

| Evron et al., 2005, N = 88 [17] | B: 20–70 µg LO: 3 min | Pethidine IV 75 mg (+ 75 mg + 50 mg if needed) | Remifentanil resulted in significantly lower VAS scores |

| Ng et al., 2011, N = 69 [25] | B: 25–30 µg LO: 3.75–4.5 min | Pethidine IM 50–75 mg | Remifentanil provided significantly lower pain scores |

| Blair et al., 2005, N = 39 [26] | B: 40 µg LO: 2 min | Pethidine IV B 15 mg LO 10 min | No difference |

| Volikas et al., 2001, N = 17 [27] | B: 0.5 µg/kg LO: 2 min | Pethidine IV 10 mg LO 5 min | Remifentanil resulted in significantly reduced hourly VAS |

| Stourac et al., 2014, N = 24 [28] | B: 20 µg LO: 3 min | EA: bupivacaine 0.125% + sufentanil 0.5 µg/mL LD 10 mL + 5 mL/60–90 min | No difference |

| Tveit et al., 2012, N = 37 [36] | B: 0.15 µg/kg + increase 0.15 µg/kg until relief LO: 2 min | EA: ropivacaine 0.1% + fentanyl 2 µg/mL LD 10 mL + inf 5–15 mL/h + rescue 5 ml | Remifentanil was inferior to EA |

| Volmanen et al., 2008, N = 45 [16] | B: 0.1–0.9 µg/kg LO: 1 min | EA: levobupivacaine 0.625 mg/mL + fentanyl 20 µg/mL B 20 ml | Remifentanil was inferior to EA |

| Douma et al., 2011, N = 20 [37] | B: 40 µg LO: 2 min | 0.2% ropivacaine B 12.5 mL + 0.1% ropivacaine + sufentanil 0.5 µg/mL inf 10 mL/h | Remifentanil was inferior to EA |

| Ismail et al., 2012, N = 1140 [38] | B: 0.1/0.9 µg/kg LO: 1 min | EA: 0.125% levobupivacaine + 2 µg/mL fentanyl 8 mL LD + inf 8 mL/h CSE: B spinal levobupivacaine 2 mg + fentanyl 15 µg; epidural 0.125% levobupivacaine + 2 µg/mL fentanyl 8 mL LD + inf 8 mL/h | CSE was superior to EA and remifentanil |

| Stocki et al., 2014, N = 39 [29] | B: 20–60 µg LO: 1–2 min | EA: 0.1% bupivacaine + fentanyl 2 µg/mL LD 15 mL + inf 5 mL/h + rescue 10 mL/20 min | Remifentanil was inferior to EA |

| Balcioglu et al., 2007, N = 60, [39] | Compared two background infusions; Fixed B: 0.15 µg I1: 0.1 µg/kg/min I2: 0.15 µg/kg/min | Not applicable; compared two background infusions of remifentanil | Higher background infusion provided lower VAS scores |

| Balki et al., 2007, N = 20, [40] | Compared two dosing regimens; B1: 0.25 µg/kg + I1: 0.025–0.1 µg/kg/min B2: 0.25–1 µg/kg + I2: 0.025 µg/kg/min | Not applicable; compared two dosing regimens of remifentanil | No significant difference between groups in pain scores |

| Freeman et al., 2015, N = 1414 [41] | B: 20–40 µg LO: 3 min | According to local protocol | Remifentanil resulted in significantly higher mean pain intensity scores |

| Logtenberg et al., 2016, N = 409 [30] | B: 30 µg LO: 3 min | 0.2% ropivacaine 12.5 mL LD + inf 0.1% ropivacaine + sufentanil 0.5 µg/mL | Remifentanil resulted in significantly higher pain intensity scores |

| Volmanen et al., 2005, N = 15 [22] | B: 0.4 µg/kg LO: 1 min | 50% N2O | Remifentanil provided significantly better pain-relieving scores |

| Thurlow et al., 2002, N = 36 [42] | B: 20 µg LO: 3 min | Pethidine IM 100 mg | Remifentanil provided significantly better pain-relieving scores |

| Wilson et al., 2018, N = 400 [18] | B: 40 µg LO: 2 min | Pethidine IM 100 mg/4 h max 400 mg | Remifentanil resulted in a significantly greater reduction in median VAS scores |

| Meta-Analysis | N of RCTs | Analgesia Methods | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2017 [20] | 8 | Remifentanil-PCA vs. EA | Significantly higher average VAS scores and VAS at 1 h in remifentanil-PCA Effect size difference: 1.33 points (95%CI 0.3 to 2.36) |

| Liu et al., 2014 [21] | 5 | Remifentanil-PCA vs. EA | Remifentanil inferior to EA for analgesic efficacy measured by VAS scores Effect size difference: 3 points (95%CI 0.7 to 5.2) |

| Schnabel et al., 2012 [19] | 12 | Remifentanil-PCA vs. EA, pethidine, N2O, fentanyl | Remifentanil-PCA superior to pethidine, inferior to EA for analgesic efficacy |

| Stourac et al., 2016 [15] | 15 | Remifentanil-PCA | Significant decrease in VAS (−2.826 points) during the first hour |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vovk Racman, P.; Lučovnik, M.; Stopar Pintarič, T. Current Perspectives on Remifentanil-PCA for Labor Analgesia: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091550

Vovk Racman P, Lučovnik M, Stopar Pintarič T. Current Perspectives on Remifentanil-PCA for Labor Analgesia: A Narrative Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091550

Chicago/Turabian StyleVovk Racman, Pia, Miha Lučovnik, and Tatjana Stopar Pintarič. 2025. "Current Perspectives on Remifentanil-PCA for Labor Analgesia: A Narrative Review" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091550

APA StyleVovk Racman, P., Lučovnik, M., & Stopar Pintarič, T. (2025). Current Perspectives on Remifentanil-PCA for Labor Analgesia: A Narrative Review. Medicina, 61(9), 1550. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091550