General Practitioner’s Practice in Romanian Children with Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Practice

3.2. Clinical Signs and Symptoms

3.3. Laboratory Tests

3.4. Differential Diagnosis

3.5. Treatment of GAS Pharyngitis

3.6. Follow-Up of a Patient with GAS Pharyngitis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAS | Beta-hemolytic group A streptococcus |

| GP | General practitioner |

| ENT | Ear–nose–throat |

| RADT | Rapid antigen detection test |

References

- Carapetis, J.R.; Steer, A.C.; Mulholland, E.K.; Weber, M. The Global Burden of Group A Streptococcal Diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Guideline on the Prevention and Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240100077 (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Centor, R.M.; Witherspoon, J.M.; Dalton, H.P.; Brody, C.E.; Link, K. The Diagnosis of Strep Throat in Adults in the Emergency Room. Med. Decis. Mak. 1981, 1, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIsaac, W.J.; White, D.; Tannenbaum, D.; Low, D.E. A Clinical Score to Reduce Unnecessary Antibiotic Use in Patients with Sore Throat. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1998, 158, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Poses, R.M.; Cebul, R.D.; Collins, M.; Fager, S.S. The Accuracy of Experienced Physicians’ Probability Estimates for Patients with Sore Throats. Implications for Decision Making. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1985, 254, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, W.L.; Arnup, S.; Danchin, M.; Steer, A.C. Rapid Diagnostic Tests for Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics 2014, 134, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.; Bertille, N.; Cohen, R.; Chalumeau, M. Rapid Antigen Detection Test for Group A Streptococcus in Children with Pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 7, CD010502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthys, J.; De Meyere, M.; van Driel, M.L.; De Sutter, A. Differences among International Pharyngitis Guidelines: Not Just Academic. Ann. Fam. Med. 2007, 5, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronman, M.P.; Zhou, C.; Mangione-Smith, R. Bacterial Prevalence and Antimicrobial Prescribing Trends for Acute Respiratory Tract Infections. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e956–e965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.M.; Shapiro, D.J.; Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; Hicks, L.A.; Hersh, A.L.; Kronman, M.P. Antibiotic Prescribing for Children in United States Emergency Departments: 2009–2014. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20181056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Raghuwanshi, S.K.; Asati, D.P. Antibiotic Use in Sore Throat: Are We Judicious? Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015, 67, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingale, M.H.; Mahajan, G.D. Evaluation of Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern in Acute Tonsillitis. Int. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 4, 1162–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Darod, H.H.; Melese, A.; Kibret, M.; Mulu, W. Throat Swab Culture Positivity and Antibiotic Resistance Profiles in Children 2-5 Years of Age Suspected of Bacterial Tonsillitis at Hargeisa Group of Hospitals, Somaliland: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 2023, 6474952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, V.D.; Bar, G.; Filimon, C.; Gaidamut, V.A.; Craiu, M. Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children: A Tertiary Pediatric Hospital in Bucharest, Romania. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2021, 13, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shulman, S.T.; Bisno, A.L.; Clegg, H.W.; Gerber, M.A.; Kaplan, E.L.; Lee, G.; Martin, J.M.; Van Beneden, C. Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, e86–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B.H.; Coomar, D.; Baragilly, M. Comparison of Centor and McIsaac Scores in Primary Care: A Meta-Analysis over Multiple Thresholds. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e245–e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa Júnior, A.R.; Oliveira, C.D.L.; Fontes, M.J.F.; Lasmar, L.M.d.L.B.F.; Camargos, P.A.M. Diagnosis of streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis in children and adolescents: Clinical picture limitations. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2014, 32, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.M.; Gilio, A.E.; Hsin, S.H.; Machado, B.M.; de Paulis, M.; Lotufo, J.P.B.; Martinez, M.B.; Grisi, S.J.E. Impact of the Rapid Antigen Detection Test in Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Pharyngotonsillitis in a Pediatric Emergency Room. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2013, 31, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, K.; Bhardwaj, P.; Gupta, A.; Mehra, S.; Nehra, D.; Nanda, S. Role of Epidemiological Risk Factors in Improving the Clinical Diagnosis of Streptococcal Sore Throat in Pediatric Clinical Practice. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3130–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, R.; Orda, U.; Elliott, B.; Heal, C.; Del Mar, C. What Is the Optimal Strategy for Managing Primary Care Patients with an Uncomplicated Acute Sore Throat? Comparing the Consequences of Nine Different Strategies Using a Compilation of Previous Studies. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orda, U.; Gunnarsson, R.; Orda, S.; Fitzgerald, M.; Rofe, G.; Dargan, A. Etiologic Predictive Value of a Rapid Immunoassay for the Detection of Group A Streptococcus Antigen from Throat Swabs in Patients Presenting with a Sore Throat. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 45, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orda, U.; Mitra, B.; Orda, S.; Fitzgerald, M.; Gunnarsson, R.; Rofe, G.; Dargan, A. Point of Care Testing for Group A Streptococci in Patients Presenting with Pharyngitis Will Improve Appropriate Antibiotic Prescription. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2016, 28, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson, M.S.; Sundvall, P.-D.; Gunnarsson, R. In Primary Health Care, Never Prescribe Antibiotics to Patients Suspected of Having an Uncomplicated Sore Throat Caused by Group A Beta-Haemolytic Streptococci without First Confirming the Presence of This Bacterium. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 44, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldan-Gradalska, P.; Gradalski, W.; Gunnarsson, R.K.; Sundvall, P.-D.; Rystedt, K. Is Streptococcus Pyogenes a Pathogen or Passenger in Uncomplicated Acute Sore Throat? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 145, 107100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, R.K.; Holm, S.E.; Söderström, M. The Prevalence of Beta-Haemolytic Streptococci in Throat Specimens from Healthy Children and Adults. Implications for the Clinical Value of Throat Cultures. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 1997, 15, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson, R.K.; Lanke, J. The Predictive Value of Microbiologic Diagnostic Tests If Asymptomatic Carriers Are Present. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyarchuk, O.; Mochulska, O.; Komorovsky, R. Diagnosis and Management of Pharyngitis in Children: A Survey Study in Ukraine. Germs 2021, 11, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröndal, H.; Hedin, K.; Strandberg, E.L.; André, M.; Brorsson, A. Near-Patient Tests and the Clinical Gaze in Decision-Making of Swedish GPs Not Following Current Guidelines for Sore Throat-a Qualitative Interview Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallon, J.; Sundqvist, M.; Hedin, K. The Use and Usefulness of Point-of-Care Tests in Patients with Pharyngotonsillitis-an Observational Study in Primary Health Care. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Vilaseca, I.; Lehrer-Coriat, E.; Boleda, X.; Cañada, J.L.; Moragas, A.; Cots, J.M. Survey of Spanish General Practitioners’ Attitudes toward Management of Sore Throat: An Internet-Based Questionnaire Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2017, 18, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiter, T.; Haering, M.; Bradic, S.; Coutinho, G.; Kostev, K. Reducing Antibiotic Misuse through the Use of Point-of-Care Tests in Germany: A Survey of 1257 Medical Practices. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESCMID Sore Throat Guideline, Group; Pelucchi, C.; Grigoryan, L.; Galeone, C.; Esposito, S.; Huovinen, P.; Little, P.; Verheij, T. Guideline for the Management of Acute Sore Throat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18 (Suppl. S1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashavya, S.; Pines, N.; Gayego, A.; Schechter, A.; Gross, I.; Moses, A. The Use of Bacterial DNA from Saliva for the Detection of GAS Pharyngitis. J. Oral. Microbiol. 2020, 12, 1771065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, A.E.; Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L.; Cordoba, G. Short- vs. Long-Course Antibiotic Treatment for Acute Streptococcal Pharyngitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meletis, G.; Soulopoulos Ketikidis, A.L.; Floropoulou, N.; Tychala, A.; Kagkalou, G.; Vasilaki, O.; Mantzana, P.; Skoura, L.; Protonotariou, E. Antimicrobial Resistance Rates of Streptococcus Pyogenes in a Greek Tertiary Care Hospital: 6-Year Data and Literature Review. New Microbiol 2023, 46, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Imöhl, M.; van der Linden, M. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Invasive Streptococcus Pyogenes Isolates in Germany during 2003–2013. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reinholdt, K.B.; Rusan, M.; Hansen, P.R.; Klug, T.E. Management of Sore Throat in Danish General Practices. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergova, R.T.; Petrova, G.; Gergov, S.; Minchev, P.; Mitov, I.; Strateva, T. Microbiological Features of Upper Respiratory Tract. Infections in Bulgarian Children for the Period. 1998–2014. Balk. Med. J. 2016, 33, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keuleyan, E.; Todorov, T.; Donchev, D.; Kevorkyan, A.; Vazharova, R.; Kukov, A.; Todorov, G.; Georgieva, B.; Altankova, I.; Uzunova, Y. Characterization of Streptococcus Pyogenes Strains from Tonsillopharyngitis and Scarlet Fever Resurgence, 2023—FIRST Detection of M1UK in Bulgaria. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karászi, É.; Kassa, C.; Tóth, K.; Onozó, B.; Erlaky, H.; Lakatos, B. A Hazai A-Csoportú Streptococcus (GAS-) Járvány Jellemzői a Gyermek-Alapellátásban 2023-Ban. Orv. Hetil. 2025, 166, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajdács, M.; Ábrók, M.; Lázár, A.; Burián, K. Beta-Haemolytic Group A, C and G Streptococcal Infections in Southern Hungary: A 10-Year Population-Based Retrospective Survey (2008–2017) and a Review of the Literature. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4739–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Your age? (years) | n = 56 |

| 29–35 | 11 (19.6%) |

| 36–45 | 22 (39.3%) |

| 46–55 | 4 (7.1%) |

| 56–65 | 12 (21.4%) |

| >65 | 7 (12.5%) |

| Praxis in: | n = 56 |

| Urban area | 34 (60.7%) |

| Rural area | 22 (39.3%) |

| Your gender | n = 56 |

| Male | 9 (16.1%) |

| Female | 47 (83.9%) |

| Number of children treated in your practice | n = 56 |

| 0–50 | 4 (7.1%) |

| 51–100 | 4 (7.1%) |

| 101–200 | 11 (19.6%) |

| >200 | 37 (66.1%) |

| How many GAS-pharyngitis per month have you treated last year? | n = 56 |

| <5 | 18 (32.1%) |

| 5–10 | 20 (35.7%) |

| >10 | 18 (32.1%) |

| What symptoms you think are suggestive for GAS-pharyngitis? | n = 56 |

| Fever > 38 °C | 48 (85.7%) |

| Swollen and tender anterior cervical adenopathy | 46 (82.1%) |

| Swollen tonsils with white exudate | 52 (92.9%) |

| Sore throat | 41 (73.2%) |

| Lack of appetite | 24 (42.9%) |

| Cough | 10 (17.9%) |

| Vomiting | 28 (50%) |

| Do you use the CENTOR Criteria for diagnosis of GAS? | n = 56 |

| Yes | 14 (25%) |

| No | 42 (75%) |

| Do you use a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) in your practice? | n = 56 |

| Yes | 6 (10.7%) |

| No | 50 (89.3%) |

| Do you request throat culture in all cases when GAS-pharyngitis is suspected? | n = 56 |

| Yes | 24 (42.9%) |

| No | 32 (57.1%) |

| You will make differential diagnosis with …. | n = 56 |

| Mononucleosis infectiosa | 51 (91.1%) |

| Peritonsillar abscess | 32 (57.1%) |

| Viral pharyngitis | 45 (80.4%) |

| Scarlet fever | 33 (58.9%) |

| Rhinopharyngitis | 36 (64.3%) |

| Do you start treatment after you have confirmed clinically the GAS-pharyngitis? | n = 56 |

| Yes, immediately | 48 (85%) |

| Yes, but only after a positive throat swab result | 8 (15%) |

| No | 0 (0%) |

| If YES, how you will treat the patient? | n = 56 |

| Targeted antibiotic therapy | 39 (69.6%) |

| Empirical antibiotic therapy | 21 (37.5%) |

| Symptomatic treatment | 8 (14.3%) |

| Non-drug symptomatic treatment (home remedies) | 4 (7.1%) |

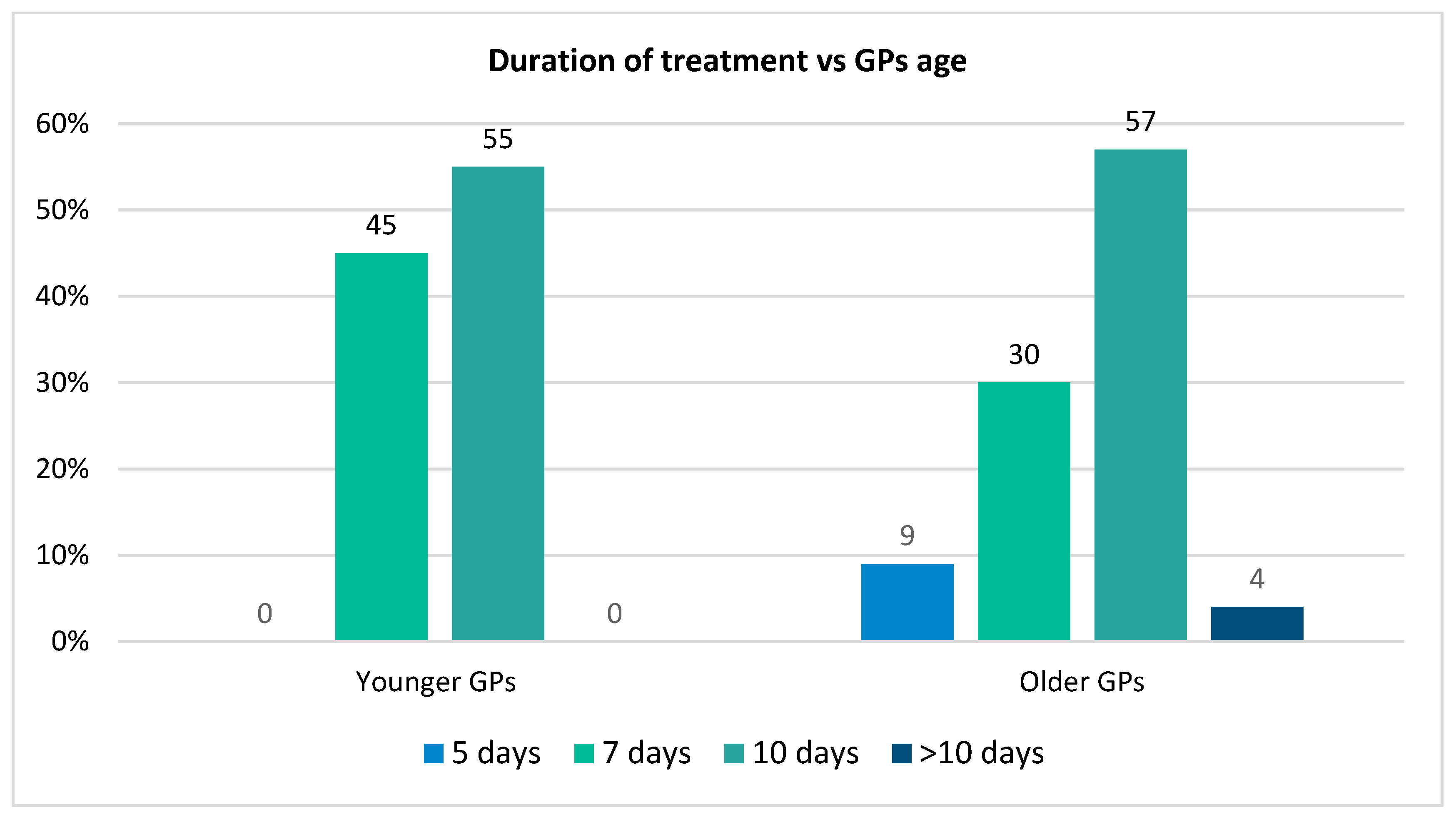

| How long will you treat the GAS patient? | n = 56 |

| 5 days | 2 (3.6%) |

| 7 days | 22 (39.3%) |

| 10 days | 31 (55.4%) |

| >10 days | 1 (1.8%) |

| Which antibiotic do you use most often as first choice? | n = 56 |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 31 (55.4%) |

| Penicillin V (po) | 22 (39.3%) |

| Erythromycin | 6 (10.7%) |

| Clindamycin | 1 (1.8%) |

| 3rd generation Cephalosporin | 3 (5.4%) |

| 2nd generation Cephalosporin | 5 (8.9%) |

| Penicillin G (iv) | 10 (17.9%) |

| Does access to medicines influence antibiotic choice? | n = 56 |

| Yes | 50 (89.3%) |

| No | 6 (10.7%) |

| Which route of antibiotic administration do you prefer? | n = 56 |

| Per oral | 50 (89%) |

| Intravenous | 5 (9%) |

| Do you recall your patient for a follow-up visit? | n = 56 |

| Yes, always | 54 (96.4%) |

| No | 2 (3.6%) |

| Yes, only if its evolution is not appropriate | 0 (0%) |

| When do you refer the patient to a pediatric specialist? | n = 56 |

| From the onset | 0 (0%) |

| If the symptoms worsen despite treatment | 20 (35.71%) |

| If I have exhausted outpatient treatment options | 13 (23.23%) |

| If the patient has a low compliance for p.o. treatment | 8 (14.28%) |

| If complications appear (e.g., scarlet fever, acute glomerulonephritis, etc.) | 15 (26.78%) |

| Do you use the ASLO titer to follow up patients? | n = 56 |

| Yes | 27 (48.2%) |

| No | 29 (51.8%) |

| Do you treat asymptomatic patients with high ASLO titers? | n = 56 |

| No | 22 (39.3%) |

| No, but I follow the dynamics of ASLO values | 29 (51.8%) |

| Yes | 5 (8.9%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balas, R.B.; Meliț, L.E.; Lupu, A.; Sandor, B.; Borka Balas, A.; Mărginean, C.O. General Practitioner’s Practice in Romanian Children with Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081408

Balas RB, Meliț LE, Lupu A, Sandor B, Borka Balas A, Mărginean CO. General Practitioner’s Practice in Romanian Children with Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081408

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalas, Reka Borka, Lorena Elena Meliț, Ancuța Lupu, Boglarka Sandor, Anna Borka Balas, and Cristina Oana Mărginean. 2025. "General Practitioner’s Practice in Romanian Children with Streptococcal Pharyngitis" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081408

APA StyleBalas, R. B., Meliț, L. E., Lupu, A., Sandor, B., Borka Balas, A., & Mărginean, C. O. (2025). General Practitioner’s Practice in Romanian Children with Streptococcal Pharyngitis. Medicina, 61(8), 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081408