Application of Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Real-World Data Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

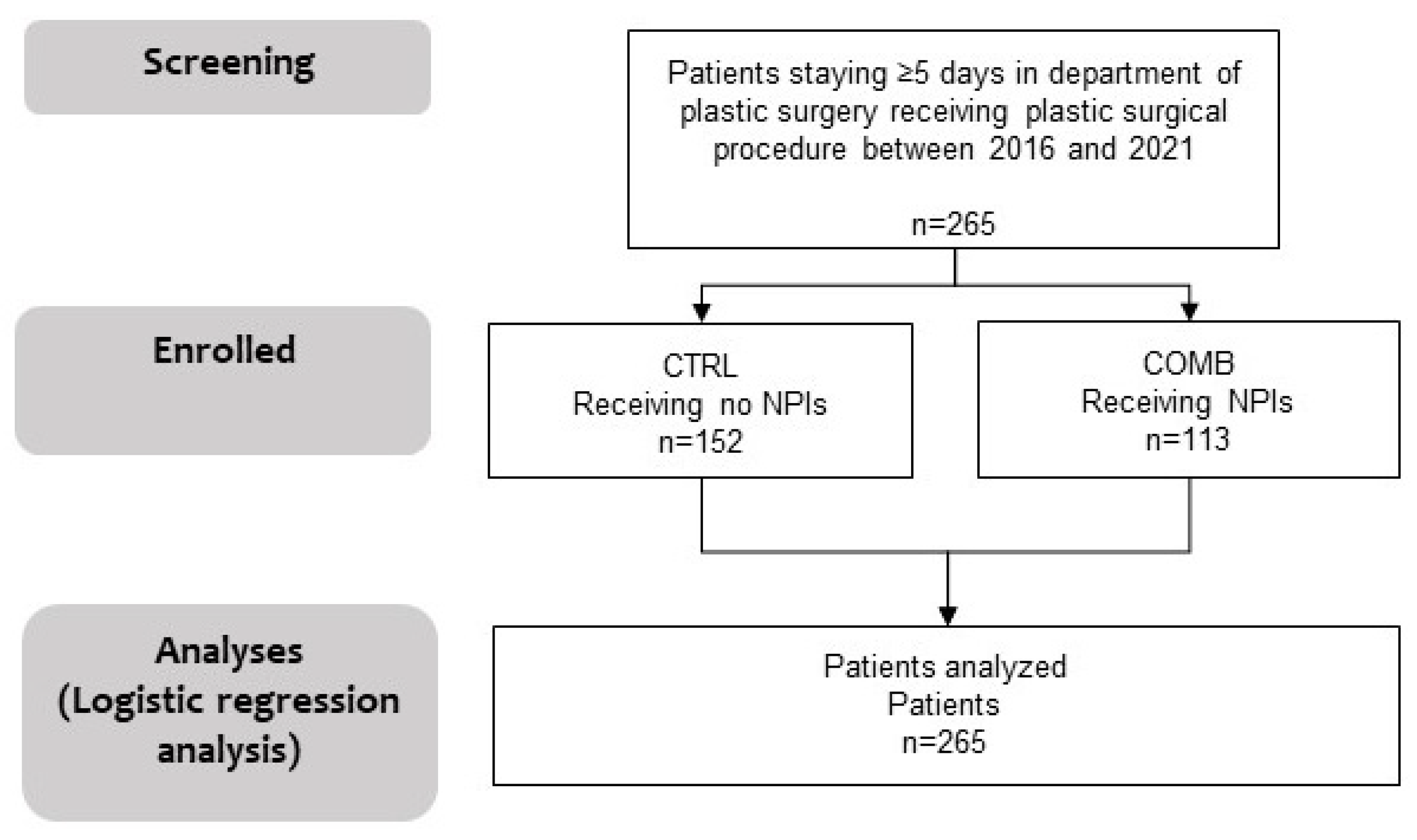

2.1. Study Design, Description of Study Participants, and Data Source Assessment

2.2. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.4. Plastic Surgery Procedures

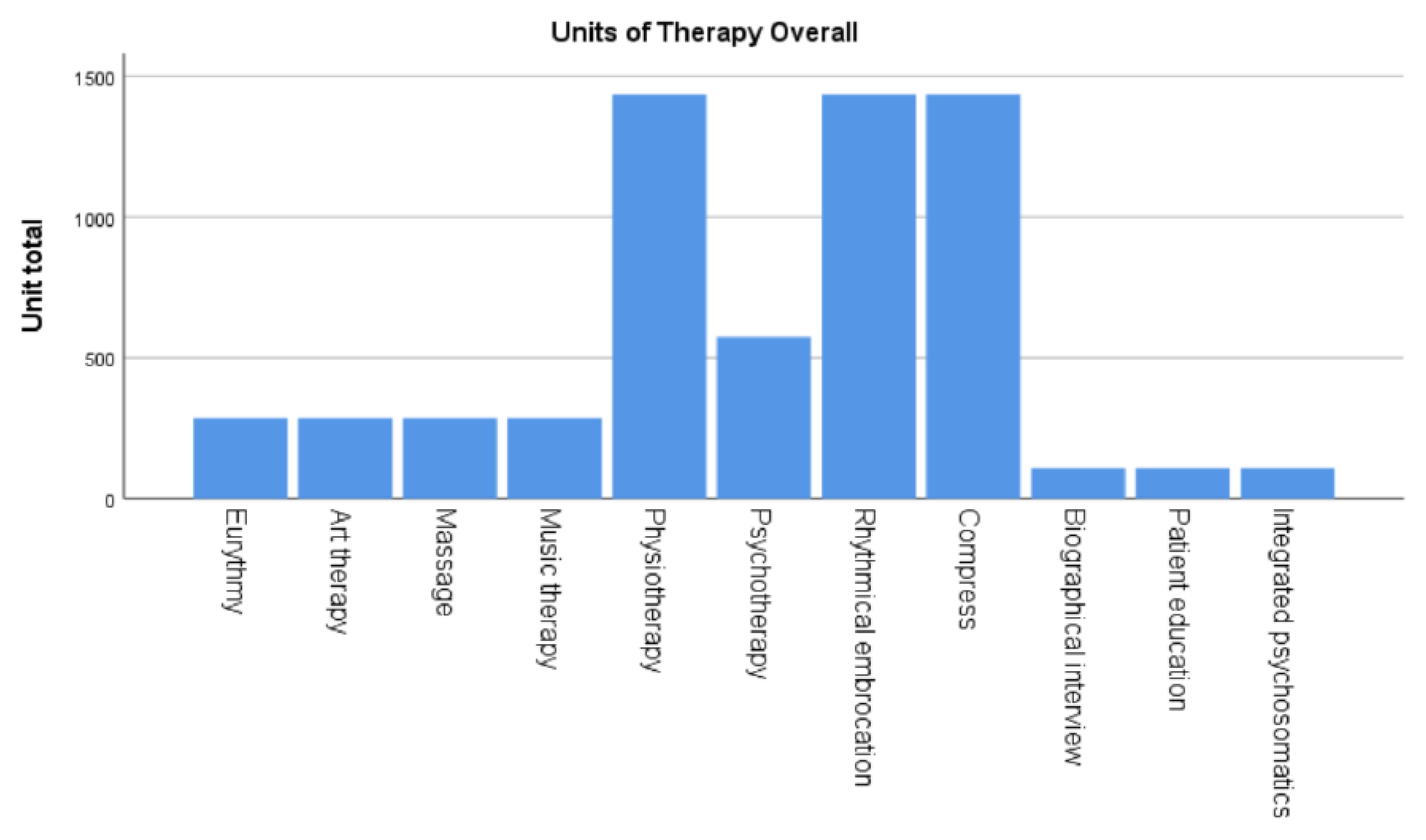

2.5. Complementary Procedures

- Eurythmy

- Breathing Therapy

- Painting therapy

- Music therapy

- Massages

- Rhythmical embrocations

- Compresses

- Physiotherapy

- Biographical interviews

- Psychoeducation and Integrated psychosomatics

3. Results

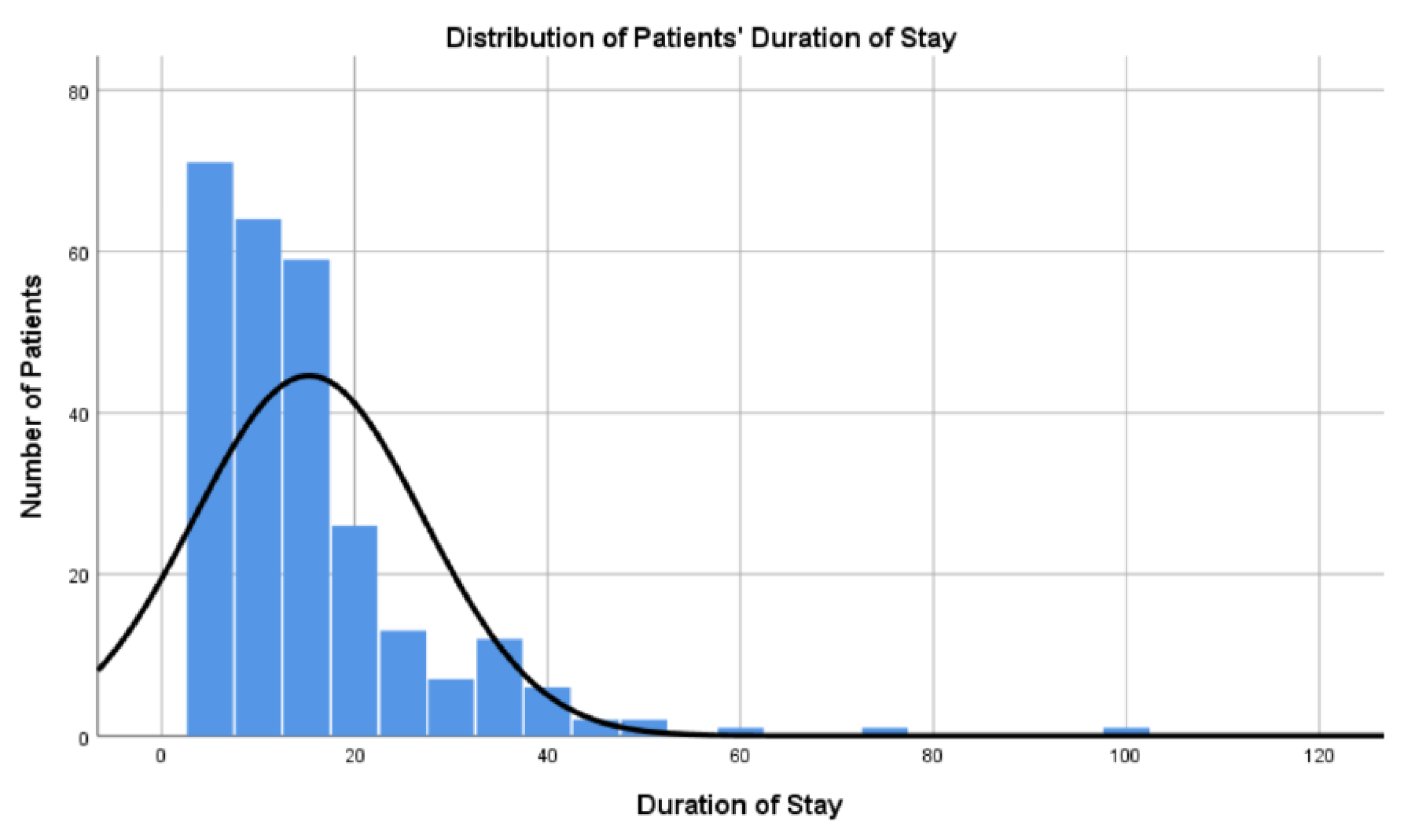

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Plastic Surgery

3.3. Non-Pharmacological Therapies

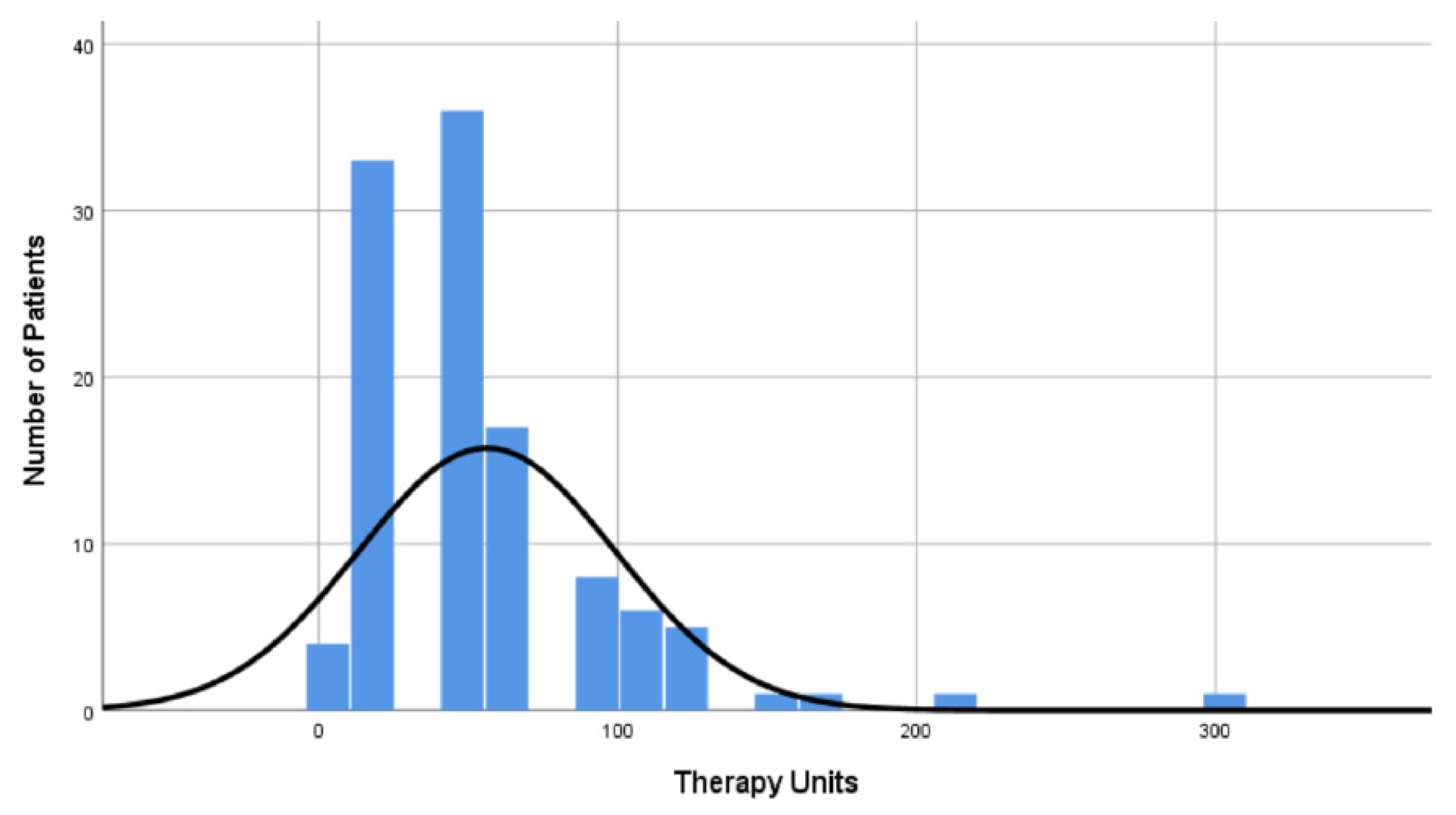

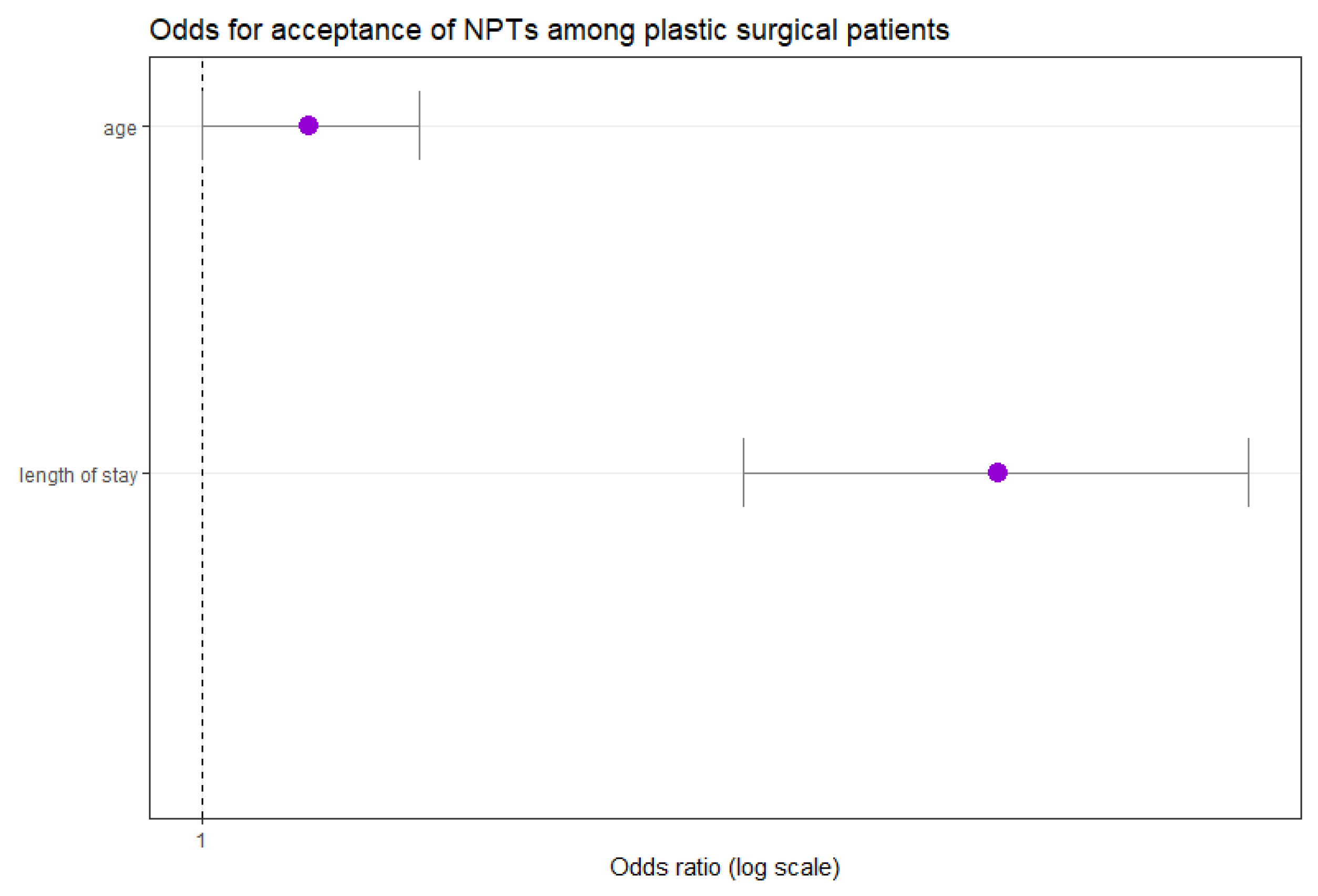

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seetharaman, M.; Krishnan, G.; Schneider, R.H. The Future of Medicine: Frontiers in Integrative Health and Medicine. Medicina 2021, 57, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D. Holistic integrative medicine: Toward a new era of medical advancement. Front. Med. 2017, 11, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thronicke, A.; Oei, S.L.; Merkle, A.; Herbstreit, C.; Lemmens, H.-P.; Grah, C.; Kröz, M.; Matthes, H.; Schad, F. Integrative cancer care in a certified Cancer Centre of a German Anthroposophic hospital. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 40, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.; Kanitz, J.-L.; Rihs, C.; Krause, I.; Witt, K.; Voss, A. Rhythmical massage improves autonomic nervous system function: A single-blind randomised controlled trial. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 16, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.Z.; Chen, A.D.; Tran, B.N.N.; Epstein, S.; Fukudome, E.Y.; Tobias, A.M.; Lin, S.J.; Lee, B.T.; Yeh, G.Y.; Singhal, D. Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Systematic Review of Our Literature. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 82, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megas, I.-F.; Tolzmann, D.S.; Bastiaanse, J.; Fuchs, P.C.; Kim, B.-S.; Kröz, M.; Schad, F.; Matthes, H.; Grieb, G. Integrative Medicine and Plastic Surgery: A Synergy-Not an Antonym. Medicina 2021, 57, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hole, J.; Hirsch, M.; Ball, E.; Meads, C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2015, 386, 1659–1671, Erratum in Lancet 2015, 386, 1630. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61181-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yu, L.; Yang, Y.; Deng, J.; Shao, L.; Zeng, C. Effects of Perioperative Music Therapy on Patients with Postoperative Pain and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2024, 30, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydın, L.Z.; Doğan, A. The Effect of Guided Imagery on Postoperative Pain Management in Patients Undergoing Lower Extremity Surgical Operations: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthop. Nurs. 2023, 42, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, K.; Aygin, D. Efficacy of Guided Imagery for Postoperative Symptoms, Sleep Quality, Anxiety, and Satisfaction Regarding Nursing Care: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. PeriAnesth. Nurs. 2019, 34, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffler, M.; Koranyi, S.; Meissner, W.; Strauß, B.; Rosendahl, J. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions for procedural pain relief in adults undergoing burn wound care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Burns 2018, 44, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.B.; Pierson, J.; Lee, T.B.; Mast, B.; Lee, B.T.; Estores, I.; Singhal, D. Utilization and Perception of Integrative Medicine Among Plastic Surgery Patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2017, 78, 557–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barqawi, A.; Egbaria, A.; Omari, A.; Abubaji, N.; Abushamma, F.; Koni, A.A.; Zyoud, S.H. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among surgical patients: A cross-sectional study. Perioper. Med. 2024, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Chen, Z. A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions used for pain relief after orthopedic surgical procedures. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.; Peck, S.; Collins, C.; Eades, G. The meaning and value of taking part in a person-centred arts programme to hospital-based stroke patients: Findings from a qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, H.; Shalaby, R.; Owusu, E.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, V.I.O.; Wei, Y. A Scoping Review of Adult Inpatient Satisfaction with Mental Health Services. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pintas, S.; Zhang, A.; James, K.J.; Lee, R.M.; Shubov, A. Effect of Inpatient Integrative Medicine Consultation on 30-Day Readmission Rates: A Retrospective Observational Study at a Major U.S. Academic Hospital. J. Integr. Complement. Med. 2022, 28, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.E.; Nguyen, N.H.; Cascavita, C.T.; Shariati, K.; Patel, A.K.; Chen, W.; Kang, Y.; Ren, X.; Tseng, C.H.; Hidalgo, M.A.; et al. The Impact of Psychological Prehabilitation on Surgical Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Ann. Surg. 2025, 281, 928–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L.M.; Gardner, V.; Bates, D.; Mason, S.; Nemecek, J.; DiFiore, J.B.; Bena, J.; Li, M.; Bethoux, F. Impact of Music Therapy on Hospitalized Patients Post-Elective Orthopaedic Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthop. Nurs. 2018, 37, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühlmann, A.Y.R.; de Rooij, A.; Kroese, L.F.; van Dijk, M.; Hunink, M.G.M.; Jeekel, J. Meta-analysis evaluating music interventions for anxiety and pain in surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kienle, G.S.; Albonico, H.-U.; Baars, E.; Hamre, H.J.; Zimmermann, P.; Kiene, H. Anthroposophic medicine: An integrative medical system originating in europe. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tola, Y.O.; Chow, K.M.; Liang, W. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in patients undergoing breast cancer surgery: A systematic review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 3369–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, R.K.; Olsen, B.F.; Rygh, L.; Moi, A.L. Pain relief from nonpharmacological interventions in the intensive care unit: A scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, S.L.; Thronicke, A.; Matthes, H.; Schad, F. Assessment of integrative non-pharmacological interventions and quality of life in breast cancer patients using real-world data. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 265 (100) |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 65 (52–80) |

| Gender | |

| Male, n (%) | 115 (43.3) |

| Female, n (%) | 150 (56.6) |

| Stay duration, days, median (IQR) | 12 (7–8) |

| Types | Number of Patients (n = 265) | Percent % |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstructive surgery 1, n (%) | 240 1 | 90.6 |

| Hand surgery, n (%) | 15 | 5.7 |

| Aesthetic surgery, n (%) | 7 | 2.6 |

| Oncological surgery, n (%) | 1 | 0.4 |

| Burn surgery 2, n (%) | 2 2 | 0.8 |

| Year of Patient’s Admittance to Hospital | Patients per Year (Stay in Hospital > 5 Days) | Patients Receiving NPIs |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 21 | 9 (42.9) |

| 2017 | 46 | 26 (56.5) |

| 2018 | 35 | 8 (22.9) |

| 2019 | 70 | 26 (37.1) |

| 2020 | 42 | 30 (71.4) |

| 2021 | 51 | 14 (27.5) |

| Total | 265 | 113 (42.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freytag, D.L.; Thronicke, A.; Bastiaanse, J.; Megas, I.-F.; Breidung, D.; Güler, I.; Matthes, H.; Johnson, S.; Schad, F.; Grieb, G. Application of Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Real-World Data Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081405

Freytag DL, Thronicke A, Bastiaanse J, Megas I-F, Breidung D, Güler I, Matthes H, Johnson S, Schad F, Grieb G. Application of Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Real-World Data Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081405

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreytag, David Lysander, Anja Thronicke, Jacqueline Bastiaanse, Ioannis-Fivos Megas, David Breidung, Ibrahim Güler, Harald Matthes, Sophia Johnson, Friedemann Schad, and Gerrit Grieb. 2025. "Application of Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Real-World Data Study" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081405

APA StyleFreytag, D. L., Thronicke, A., Bastiaanse, J., Megas, I.-F., Breidung, D., Güler, I., Matthes, H., Johnson, S., Schad, F., & Grieb, G. (2025). Application of Integrative Medicine in Plastic Surgery: A Real-World Data Study. Medicina, 61(8), 1405. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081405