Psychological Resilience Buffers Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due to Childhood Trauma in Thai Seniors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Self-Developed Sociodemographic and Health Condition Questionnaire

2.3.2. Instruments

Modified Traumatic Experience Scale (TES) for Childhood Trauma

Lifetime Traumatic Experience

9-Item Resilience Inventory (RI-9)

Thai Geriatric Depression Scale-6 (TGDS-6)

PTSD Check List for Civilian (PCL-C)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Difference Within Covariates

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Moderation Analysis

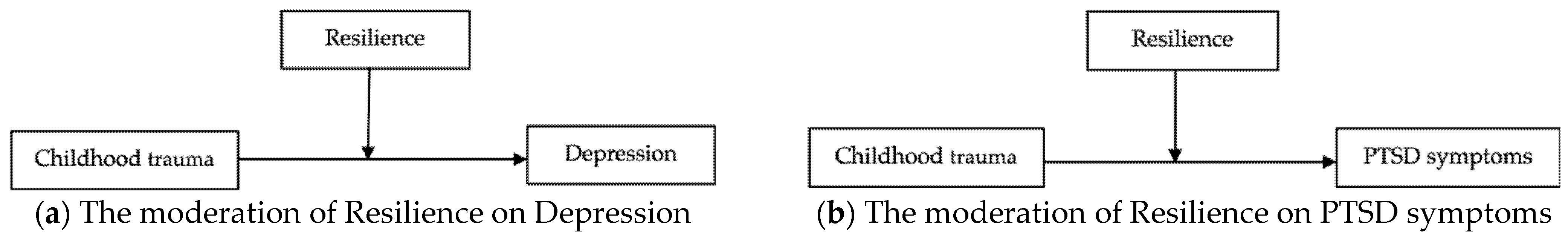

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications and Future Research

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| MBI | Mindfulness-Based Intervention |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

References

- Department of Older Persons. Situation of the Thai Older Persons; Amarin Corporations Public Company Limited: Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Yazdkhasti, M.; Rostami, M.; Ghavidel, N. Factors affecting mental health and happiness in the elderly: A structural equation model by gender differences. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, A.P.; Cook, J.M.; Glick, D.M.; Moye, J. Posttraumatic Stress. Disorder in Older Adults: A Conceptual Review. Clin. Gerontol. 2019, 42, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Kiely, K.M.; Callaghan, B.L.; Anstey, K.J. Childhood adversity is associated with anxiety and depression in older adults: A cumulative risk and latent class analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 354, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, S.M.; Mackenzie, C.S.; Henriksen, C.A.; Afifi, T.O. Time Does Not Heal All Wounds: Older Adults Who Experienced Childhood Adversities Have Higher Odds of Mood, Anxiety, and Personality Disorders. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2014, 22, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weich, S.; Patterson, J.; Shaw, R.; Stewart-Brown, S. Family relationships in childhood and common psychiatric disorders in later life: Systematic review of prospective studies. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zelst, W.H.; De Beurs, E.; Beekman, A.T.; Deeg, D.J.; Van Dyck, R. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Posttraumatic Stress. Disorder in Older Adults. Psychother. Psychosom. 2003, 72, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunea, I.M.; Szentágotai-Tătar, A.; Miu, A.C. Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: A meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammen, C.; Henry, R.; Daley, S.E. Depression and sensitization to stressors among young women as a function of childhood adversity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 68, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclaughlin, K.A.; Conron, K.J.; Koenen, K.C.; Gilman, S.E. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippard, E.T.C.; Nemeroff, C.B. The Devastating Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect: Increased Disease Vulnerability and Poor Treatment Response in Mood Disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrory, E.; De Brito, S.A.; Viding, E. Research Review: The neurobiology and genetics of maltreatment and adversity. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpawong, T.E.; Mekli, K.; Lee, J.; Phillips, D.F.; Gatz, M.; Prescott, C.A. A longitudinal study shows stress proliferation effects from early childhood adversity and recent stress on risk for depressive symptoms among older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2022, 26, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Stastistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5); American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Glaesmer, H.; Gunzelmann, T.; Braehler, E.; Forstmeier, S.; Maercker, A. Traumatic experiences and post-traumatic stress disorder among elderly Germans: Results of a representative population-based survey. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choksomngam, Y.; Petrungjarern, T.; Ketkit, P.; Boontak, P.; Panya, R.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Lerttrakarnnon, P. The Prevalence of Elder Abuse and its Association with Frailty in Elderly Patients at the Outpatient Department of a Super-Tertiary Care Hospital in Northern Thailand. Medicina 2023, 59, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saneha; Chongjit; Pinyopasakul, W.; Charnsri, W. Flood Disaster Experiences and Preparedness of Chronically Ill Patients and Family Caregivers in Thailand. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 33, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ritbunyakorn, N. Comparison Between the Prevalence of Probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Among Different Flood Types in Thailand. In Chulalongkorn University Theses and Dissertations; Chula Digital Collections: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sonpaveerawong, J.; Limmun, W.; Chuwichian, N. Prevalence of Psychological Distress and Mental Health Problems among the Survivors in the Flash Floods and Landslide in Southern Thailand. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. 2017, 16, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelo, M.; von Gunten, A.; Jardim, G.B.G.; Spanemberg, L.; Argimon, I.I.d.L.; Nogueira, E.L. Effects of childhood multiple maltreatment experiences on depression of socioeconomic disadvantaged elderly in Brazil. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 79, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Jin, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Ungvari, G.S.; Tang, Y.-L.; Ng, C.H.; Li, X.-H.; Xiang, Y.-T. Global prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological surveys. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 80, 103417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenebe, Y.; Akele, B.; W/Selassie, M.; Necho, M. Prevalence and determinants of depression among old age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Lerttrakarnnon, P.; Jiraniramai, S.; Sirirak, T.; Assanangkornchai, S.; Taemeeyapradit, U.; Tantirangsee, N.; Lertkachatarn, S.; Arunpongpaisal, S.; et al. Prevalence, clinical and psychosocial variables of depression, anxiety and suicidality in geriatric tertiary care settings. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2019, 41, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, D.; Purandare, N.; Conn, D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: A systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22, 1025–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, R.M.; Reynolds, C.F. Management of Depression in Older Adults: A Review. JAMA 2017, 317, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DellaCava, E.F.; Cabassa, J.; Kastenschmidt, E.; Scalmati, A. Eliciting Trauma History and PTSD Symptoms in Older Adults-Do Validated Instruments Improve Accuracy? Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, S127–S128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srifuengfung, M.; Thana-Udom, K.; Ratta-Apha, W.; Chulakadabba, S.; Sanguanpanich, N.; Viravan, N. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults living in long-term care centers in Thailand, and risk factors for post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 295, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, E.J.; Best, S.R.; Lipsey, T.L.; Weiss, D.S. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buhrmann, A.S.; Fuller-Thomson, E. Poorer physical and mental health among older adults decades after experiencing childhood physical abuse. Aging Health Res. 2022, 2, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Goldstein, R.B.; Southwick, S.M.; Grant, B.F. Physical health conditions associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in U.S. older adults: Results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sledjeski, E.M.; Speisman, B.; Dierker, L.C. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R). J. Behav. Med. 2008, 31, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, N.G.; DiNitto, D.M.; Marti, C.N.; Choi, B.Y. Association of adverse childhood experiences with lifetime mental and substance use disorders among men and women aged 50+ years. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2017, 29, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, T.G.; Barry, L.C.; Kuchel, G.A.; Steffens, D.C.; Wilkinson, S.T. Associations of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Past-Year DSM-5 Psychiatric and Substance Use Disorders in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2085–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krammer, S.; Kleim, B.; Simmen-Janevska, K.; Maercker, A. Childhood trauma and complex posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in older adults: A study of direct effects and social-interpersonal factors as potential mediators. J. Trauma Dissociation 2016, 17, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damian, A.J.; Oo, M.; Bryant, D.; Gallo, J.J.; Strutz, K. Evaluating the association of adverse childhood experiences, mood and anxiety disorders, and suicidal ideation among behavioral health patients at a large federally qualified health center. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, D.W.; Anda, R.F.; Tiemeier, H.; Felitti, V.J.; Edwards, V.J.; Croft, J.B.; Giles, W.H. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 37, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, M. Self-reported poor physical health is more common in older people with trauma exposure. Evid. Based Ment. Health 2011, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Papathanasiou, I.V.; Fradelos, E.C.; Mantzaris, D.; Rammogianni, A.; Malli, F.; Papagiannis, D.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Multimorbidity, Trauma Exposure, and Frailty of Older Adults in the Community. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 634742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheffler, J.L.; Burchard, V.; Pickett, S. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Poor Sleep Quality in Older Adults: The Influence of Emotion Regulation. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 1919–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, M.; Rice, J.; Black, S.R. Recurrence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Late Life: A Cognitive Aging Perspective. J. Clin. Geropsychology 2002, 8, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuelsdorff, M.; Sonnega, A.; Barnes, L.L.; Byrd, D.R.; Rose, D.K.; Cox, R.; Norton, D.; Turner, R.W. Childhood and Adulthood Trauma. Associate With Cognitive Aging Among Black and White Older Adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2024, 32, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donley, G.A.R.; Lönnroos, E.; Tuomainen, T.-P.; Kauhanen, J. Association of childhood stress with late-life dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: The KIHD study. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, G.A. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Westphal, M.; Mancini, A.D. Resilience to loss and potential trauma. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 511–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, D.M.; Parker, K.J.; Schatzberg, A.F. Animal models of early life stress: Implications for understanding resilience. Dev. Psychobiol. 2010, 52, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Jang, Y.; Lee, W.; Yu, H.; Yoon, J.; Oh, S.; Park, Y.S.; Ryoo, H.A.; Lee, J.; et al. Relationship between childhood trauma and resilience in patients with mood disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 323, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Obradovic, J. Disaster Preparation and Recovery Lessons from Research on Resilience in Human Development. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S.; Grych, J.; Banyard, V. Resilience portfolios and poly-strengths: Identifying protective factors associated with thriving after adversity. Psychol. Violence 2018, 8, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, H.S.; Akhlaghi, E.; Torkian, S.; Khosravi, V.; Etesami, R.; Froelicher, E.S.; Sharif, S.P. Predictors of Persistence of Anxiety, Hyperarousal Stress, and Resilience During the COVID-19 Epidemic: A National Study in Iran. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 671124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhungana, S.; Koirala, R.; Ojha, S.; Thapa, S. Resilience and its association with post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression symptomatology in the aftermath of trauma: A cross-sectional study from Nepal. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65 (Suppl. 1), 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, M.P.W.; Lucchetti, A.L.G.; Lucchetti, G. Association between depression and resilience in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva-Sauer, L.; Lima, T.R.G.; da Fonsêca, É.K.G.; de la Torre-Luque, A.; Yu, X.; Fernández-Calvo, B. Psychological Resilience Moderates the Effect of Perceived Stress on Late-Life Depression in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Trends Psychol. 2021, 29, 670–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfil, M.; Negida, A. Sampling methods in Clinical Research; an Educational Review. Emergency 2017, 5, e52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, T. 2015. Available online: https://www.wongpakaran.com/index.php?lay=show&ac=article&Id=2147664677 (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Benjet, C.; Bromet, E.; Karam, E.G.; Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Ruscio, A.M.; Shahly, V.; Stein, D.J.; Petukhova, M.; Hill, E.; et al. The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, T.; Yang, T.; Varnado, P.; Siriai, Y.; Mirnics, Z.; Kövi, Z.; Wongpakaran, N. The development and validation of a new resilience inventory based on inner strength. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Van Reekum, R. The Use of GDS-15 in Detecting MDD: A Comparison Between Residents in a Thai Long-Term Care Home and Geriatric Outpatients. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2013, 5, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F.W.; Litz, B.T.; Herman, D.S.; Huska, J.A.; Keane, T.M. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX, USA, 24–27 October 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, J.M.; Elhai, J.D.; Areán, P.A. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist with older primary care patients. J. Traum. Stress 2005, 18, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Van Ness, P.H.; Fried, T.R.; Galea, S.; Norris, F. Diagnostic utility and factor structure of the PTSD Checklist in older adults. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2012, 24, 1684–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.D.; Calhoun, P.S. The diagnostic accuracy of the PTSD Checklist: A critical review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunrasameesopa, S.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Influence of Attachment Anxiety on the Relationship between Loneliness and Depression among Long-Term Care Residents. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myint, K.M.; DeMaranville, J.; Wongpakaran, T.; Peisah, C.; Arunrasameesopa, S.; Wongpakaran, N. Meditation Moderates the Relationship between Insecure Attachment and Loneliness: A Study of Long-Term Care Residents in Thailand. Medicina 2024, 60, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingkachotivanich, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wongpakaran, N.; Oon-Arom, A.; Lohanan, T.; Leesawat, T. Different Effects of Perceived Social Support on the Relationship between Perceived Stress and Depression among University Students with Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms: A Multigroup Mediation Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oon-arom, A.; Wongpakaran, T.; Kuntawong, P.; Wongpakaran, N. Attachment anxiety, depression, and perceived social support: A moderated mediation model of suicide ideation among the elderly. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Prevalence of major depressive disorders and suicide in long-term care facilities: A report from northern Thailand. Psychogeriatrics 2012, 12, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booniam, S.; Wongpakaran, T.; Lerttrakarnnon, P.; Jiraniramai, S.; Kuntawong, P.; Wongpakaran, N. Predictors of Passive and Active Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt Among Older People: A Study in Tertiary Care Settings in Thailand. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 3135–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Cheong, E.; Sinnott, C.; Dahly, D.; Kearney, P.M. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and later-life depression: Perceived social support as a potential protective factor. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogle, C.M.; Rubin, D.C.; Siegler, I.C. Cumulative exposure to traumatic events in older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in Development and Psychopathology: Multisystem Perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotov, R.; Krueger, R.F.; Watson, D.; Achenbach, T.M.; Althoff, R.R.; Bagby, R.M.; Brown, T.A.; Carpenter, W.T.; Caspi, A.; Clark, L.A.; et al. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A Dimensional Alternative to Traditional Nosologies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017, 126, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, R.; Hyland, P.; Power, J.M.; Coogan, A.N. Patterns of comorbidity associated with ICD-11 PTSD among older adults in the United States. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Goldstein, R.B.; Southwick, S.M.; Grant, B.F. Psychiatric comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder among older adults in the United States: Results from wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 68.56 (±5.0) |

| 60–69 years | 118 (58.7%) |

| 70–79 years | 78 (38.8%) |

| 80 and above | 5 (2.5%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 141 (70.1%) |

| Male | 60 (29.9%) |

| Religion | |

| Buddhist | 194 (96.5%) |

| Non-Buddhist | 7 (3.5%) |

| Education | |

| No education | 3 (1.5%) |

| Primary education | 50 (24.9%) |

| Secondary education | 56 (27.9%) |

| Diploma | 3 (1.5%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 64 (31.8%) |

| Master’s degree and above | 25 (12.4%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 12 (6.0%) |

| Married | 140 (69.7%) |

| Divorced | 19 (9.5%) |

| Widowed | 30 (14.9%) |

| No. of household member | |

| 1 | 9 (4.5%) |

| 3 or less | 99 (49.3%) |

| 4 or more | 93 (45.3%) |

| Living status | |

| Living alone | 23 (11.4%) |

| Living with family | 173 (86.1%) |

| Living with others | 5 (2.5%) |

| Family relationship | |

| Good | 159 (79.1%) |

| Average | 42 (20.9%) |

| Poor | 0 |

| Monthly income | |

| 5000 or less | 59 (29.4%) |

| Between 5000 and 10,000 | 28 (13.9%) |

| 10,000 and above | 114 (56.7%) |

| Family history of psychiatric condition | |

| Yes | 16 (8.0%) |

| No | 185 (92.0%) |

| Medical coverage | |

| Gov. official | 168 (83.6%) |

| 30-baht scheme | 20 (10.0%) |

| Social security scheme | 5 (2.5%) |

| Health insurance | 2 (1.0%) |

| Self-paid | 6 (3.0%) |

| Alcohol consumption in the past month | |

| None | 175 (87.1%) |

| Less than 3 times a week | 20 (10.0%) |

| 3–5 times a week | 5 (2.5%) |

| More than 5 times a week | 1 (0.5%) |

| Smoking/tobacco use in the past month | |

| No | 196 (97.5%) |

| Yes | 5 (2.5%) |

| Cannabis use in the past month | |

| No | 196 (97.5%) |

| Yes | 5 (2.5%) |

| History of fall in the past month | |

| Yes | 6 (3.0%) |

| No | 195 (97%) |

| History of physical comorbidities | |

| Yes | 127 (63.2%) |

| No | 74 (36.8%) |

| History of psychiatric comorbidities | |

| Yes | 12 (6%) |

| No | 189 (94%) |

| Childhood trauma | |

| No | 120 (59.7%) |

| Yes | 81 (40.3%) |

| Lifetime trauma | |

| No | 84 (41.79%) |

| Yes | 117 (58.21%) |

| Resilience Inventory-RI (9–45) | 33.77 (±10.510) |

| Thai Geriatric Depression Scale 6 (TGDS-6) | 0.52 (±0.94) |

| Depression prevalence | 23 (11.4%) 95% CI: 7–17% |

| PTSD Check List for Civilian (PCL-C) (17–85) | 27.70 (±10.62) |

| PTSD prevalence | 23 (11.4%) 95% CI: 7–17% |

| Characteristics | Resilience Mean (SD) | Effect Size | Depression Score Mean (SD) | Effect Size | PTSD Symptoms Mean (SD) | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60–69 years | 33.93 (10.13) | η2p = 0.005 | 0.55 (0.95) | η2p = 0.026 | 27.57 (9.61) | η2p = 0.050 |

| 70–79 years | 33.03 (10.87) | 0.42 (0.83) | 26.96 (10.78) | ||||

| 80 and above | 37.20 (6.34) | 1.4 (1.95) | 42.40 (20.45) | ||||

| Sex | Female (141) | 32.59 (10.48) | Cohen’s d = 0.36 * | 0.59 (0.98) | Cohen’s d = 0.24 | 27.43 (11.11) | Cohen’s d = 0.089 |

| Male (60) | 36.18 (9.60) | 0.37 (0.82) | 28.35 (9.43) | ||||

| Education | <up to secondary | 32.86 (10.50) | η2p = 0.14 *** | 0.55 (0.98) | Cohen’s d = 0.19 | 27.48 (10.78) | Cohen’s d = 0.14 |

| >Above secondary | 38.06 (8.21) | 0.39 (0.72) | 28.90 (9.77) | ||||

| Monthly income | 5000 or less | 30.41 (11.68) | η2p = 0.073 ** | 0.66 (0.99) | η2p = 0.06 ** | 26.24 (11.29) | η2p = 0.120 |

| Between 5000 and 10,000 | 30.64 (11.13) | 1.07 (1.36) | 28.43 (12.59) | ||||

| 10,000 and above | 36.09 (8.70) | 0.32 (0.71) | 28.28 (9.74) | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 37.42 (5.43) | η2p = 0.021 | 0.58 (1.00) | η2p = 0.020 | 30.50 (10.82) | η2p = 0.034 |

| Married | 33.99 (10.29) | 0.43 (0.84) | 26.56 (9.04) | ||||

| Divorced | 33.53 (11.56) | 0.95 (1.31) | 32.63 (15.15) | ||||

| Widowed | 30.70 (10.94) | 0.67 (1.06) | 28.77 (13.14) | ||||

| Family relationship | Good | 33.94 (10.56) | Cohen’s d = 0.13 | 0.42 (0.83) | Cohen’s d = 0.46 * | 26.10 (8.34) | Cohen’s d = 0.62 ** |

| Average | 32.59 (9.47) | 0.90 (1.23) | 33.76 (15.31) | ||||

| Family history of psychiatric condition | Yes | 36.81 (8.79) | Cohen’s d = 0.36 | 1.31 (1.62) | Cohen’s d = 0.67 | 41.00 (19.13) | Cohen’s d = 0.97 ** |

| No | 33.39 (10.34) | 0.45 (0.83) | 26.55 (8.72) | ||||

| Alcohol consumption in the past month | None | 33.30 (10.55) | η2p = 0.012 | 0.53 (0.94) | η2p = 0.017 | 27.55 (10.87) | η2p = 0.0060 |

| Less than 3 times a week | 35.30 (8.96) | 0.55 (1.10) | 29.60 (9.44) | ||||

| 3–5 times a week | 37.6 (7.27) | 0.20 (0.45) | 26.80 (6.53) | ||||

| More than 5 times a week | 44 (0.00) | 1 (0.00) | 20 (0.00) | ||||

| Smoking/Tobacco use in the past month | No | 33.66 (10.38) | Cohen’s d = 0.01 | 0.48 (0.89) | Cohen’s d = 1.19 ** | 27.60 (10.64) | Cohen’s d = 0.38 |

| Yes | 33.60 (9.50) | 2.00 (1.58) | 31.60 (10.26) | ||||

| History of fall in the past month | No | 33.89 (10.14) | Cohen’s d = 0.61 | 0.50 (0.92) | Cohen’s d = 0.71 * | 27.27 (9.67) | Cohen’s d = 0.76 |

| Yes | 26.17 (14.59) | 1.33 (1.37) | 41.83 (25.28) | ||||

| History of physical comorbidities | No | 33.32 (10.59) | Cohen’s d = 0.05 | 0.54 (0.86) | Cohen’s d = 0.03 | 27.46 (9.39) | Cohen’s d = 0.04 |

| Yes | 33.86 (10.22) | 0.51 (0.99) | 27.84 (11.31) | ||||

| History of psychiatric comorbidities | No | 33.84 (10.37) | Cohen’s d = 0.29 | 0.42 (0.82) | Cohen’s d = 1.64 *** | 26.58 (8.86) | Cohen’s d = 1.28 *** |

| Yes | 30.92 (9.78) | 2.17 (1.27) | 45.33 (18.71) | ||||

| Childhood trauma | No trauma | 33.73 (11.15) | Cohen’s d = 0.01 | 0.31 (0.66) | Cohen’s d = 4.61 * | 24.78 (7.47) | Cohen’s d = 0.46 |

| At least one trauma | 33.63 (9.90) | 0.64 (1.05) | 29.33 (11.74) | ||||

| Lifetime trauma | No trauma | 32.24 (11.49) | Cohen’s d = 0.23 | 0.33 (0.79) | Cohen’s d = 0.36 * | 23.99 (7.11) | Cohen’s d = 0.65 *** |

| At least one trauma | 34.68 (9.34) | 0.66 (1.02) | 30.37 (11.88) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age in years | - | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Sex | 0.05 | - | |||||||||||||

| 3. Religion | −0.05 | 0.12 | - | ||||||||||||

| 4. Education | −0.03 | 0.19 ** | −0.03 | - | |||||||||||

| 5. Marital status | 0.16 * | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.16 * | - | ||||||||||

| 6. Living status | −0.13 | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.12 | - | |||||||||

| 7. Family relationship | 0.04 | −0.18 * | −0.04 | −0.20 ** | 0.16 * | −0.18 * | - | ||||||||

| 8. Monthly income | 0.02 | 0.32 ** | 0.06 | 0.61 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.01 | −0.22 ** | - | |||||||

| 9. Medical coverage | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.09 | −0.35 ** | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.22 ** | −0.27 ** | - | ||||||

| 10. Alcohol used in the past month | −0.07 | 0.21 ** | 0.07 | 0.14 * | −0.08 | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.22 ** | 0.04 | - | |||||

| 11. Childhood trauma | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.18 * | 0.14 * | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.06 | - | ||||

| 12. Lifetime trauma | 0.19 ** | 0 | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.04 | - | |||

| 13. Resilience | −0.03 | 0.18 * | −0.01 | 0.37 ** | −0.12 | 0.04 | −0.09 | 0.24 ** | −0.11 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.13 | - | ||

| 14. Depression | −0.02 | −0.13 | −0.02 | −0.15 * | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.19 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.25 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.25 ** | - | |

| 15. PTSD symptoms | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.15 * | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.22 ** | 0.14 * | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.14 * | 0.38 ** | 0.08 | 0.35 ** | - |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family HO psychiatric condition | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Smoking/tobacco use in the past month | 0.05 | - | |||||||||

| 3. Cannabis use in the past month | 0.05 | 0.18 * | - | ||||||||

| 4. History of fall in the past month | 0.16 * | −0.03 | −0.03 | - | |||||||

| 5. Physical comorbidity | 0.15 * | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | - | ||||||

| 6. Psychiatric comorbidity | 0.31 ** | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.10 | - | |||||

| 7. Childhood trauma | 0.1 | −0.07 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.27 ** | - | ||||

| 8. Lifetime trauma | 0.26 ** | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.20 ** | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.11 | - | |||

| 9. Resilience | 0.09 | −0.00 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −0.15 * | 0.16 * | - | ||

| 10. Depression | 0.25 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.15 * | −0.01 | 0.44 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.22 ** | - | |

| 11. PTSD symptoms | 0.37 ** | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.23 ** | 0.02 | 0.42 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.15 * | 0.51 ** | - |

| Measuring Variables | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Childhood trauma (0–25) | 0.76 (1.27) | - | ||||

| 2. Lifetime trauma (0–16) | 1.31 (1.78) | 0.11 | - | |||

| 3. Resilience (9–45) | 33.66 (10.34) | −0.15 * | 0.16 * | - | ||

| 4. Depression (0–6) | 0.53 (0.943) | 0.43 ** | 0.23 ** | −0.22 ** | - | |

| 5. PTSD symptoms (17–85) | 27.70(10.62) | 0.31 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.15 * | 0.51 ** | - |

| Model | Coeff. | SE | t | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constant | 0.37 | 0.05 | 7.63 | <0.001 | 0.273 | 0.463 |

| R2 = 0.12 | Childhood trauma (X) | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.29 | <0.001 | 0.102 | 0.254 |

| MSE = 0.475 | Resilience (W) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −2.08 | 0.039 | −0.019 | 0.000 |

| 2 | Constant | 0.35 | 0.05 | 7.36 | <0.001 | 0.260 | 0.450 |

| R2 = 0.14 | Childhood trauma (X) | 0.14 | 0.04 | 3.62 | <0.001 | 0.065 | 0.221 |

| MSE = 0.460 | Resilience (W) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −1.76 | 0.081 | −0.018 | 0.001 |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −2.17 | 0.032 | −0.013 | −0.001 | |

| 3 | Constant | 0.38 | 0.63 | 0.603 | 0.547 | −0.862 | 1.621 |

| R2 = 0.36 | Childhood trauma (X) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 2.14 | 0.034 | 0.007 | 0.160 |

| MSE = 0.364 | Resilience (W) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −1.51 | 0.133 | −0.016 | 0.002 |

| Interaction (X × W) | −0.01 | 0.00 | −3.00 | 0.003 | −0.015 | −0.003 |

| Model | Predictors | R2 | ∆R2 | f2 | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X, M | 0.12 | - | - | 12.99 | 0.000 |

| 2 | X, M, X × M (interaction) | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.023 | 10.38 | 0.000 |

| 3 | X, M, X × M (with covariates) | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.375 | 6.50 | 0.000 |

| Model | Coeff. | SE | t | p-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constant | 27.70 | 0.70 | 39.52 | <0.001 | 26.319 | 29.084 |

| R2 = 0.09 | Childhood trauma (X) | 2.83 | 0.56 | 5.04 | <0.001 | 1.723 | 3.936 |

| MSE = 102.7 | Resilience (W) | 0.21 | 0.07 | 2.99 | 0.003 | 0.070 | 3.341 |

| 2 | Constant | 27.84 | 0.70 | 39.50 | <0.001 | 26.446 | 29.225 |

| R2 = 0.14 | Childhood trauma (X) | 3.05 | 0.58 | 5.27 | <0.001 | 1.908 | 4.193 |

| MSE = 98.16 | Resilience (W) | 0.19 | 0.07 | 2.75 | 0.007 | 0.054 | 0.327 |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.48 | 0.142 | −0.023 | 0.158 | |

| 3 | Constant | 16.01 | 8.56 | 1.871 | 0.063 | −0.876 | 32.895 |

| R2 = 0.45 | Childhood trauma (X) | 1.65 | 0.53 | 3.11 | 0.002 | 0.601 | 2.692 |

| MSE = 67.32 | Resilience (W) | 0.15 | 0.06 | 2.41 | 0.017 | 0.027 | 0.270 |

| Interaction (X × W) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.634 | −0.060 | 0.099 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moe Yu, M.; Pinyopornpanish, K.; Wongpakaran, N.; O’Donnell, R.; Wongpakaran, T. Psychological Resilience Buffers Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due to Childhood Trauma in Thai Seniors. Medicina 2025, 61, 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081355

Moe Yu M, Pinyopornpanish K, Wongpakaran N, O’Donnell R, Wongpakaran T. Psychological Resilience Buffers Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due to Childhood Trauma in Thai Seniors. Medicina. 2025; 61(8):1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081355

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoe Yu, Moe, Kanokporn Pinyopornpanish, Nahathai Wongpakaran, Ronald O’Donnell, and Tinakon Wongpakaran. 2025. "Psychological Resilience Buffers Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due to Childhood Trauma in Thai Seniors" Medicina 61, no. 8: 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081355

APA StyleMoe Yu, M., Pinyopornpanish, K., Wongpakaran, N., O’Donnell, R., & Wongpakaran, T. (2025). Psychological Resilience Buffers Depression and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Due to Childhood Trauma in Thai Seniors. Medicina, 61(8), 1355. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61081355