Patients’ Experiences of the Treatment Received During Their Stay in the Stroke Unit at Spanish Healthcare Centers: A Qualitative Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

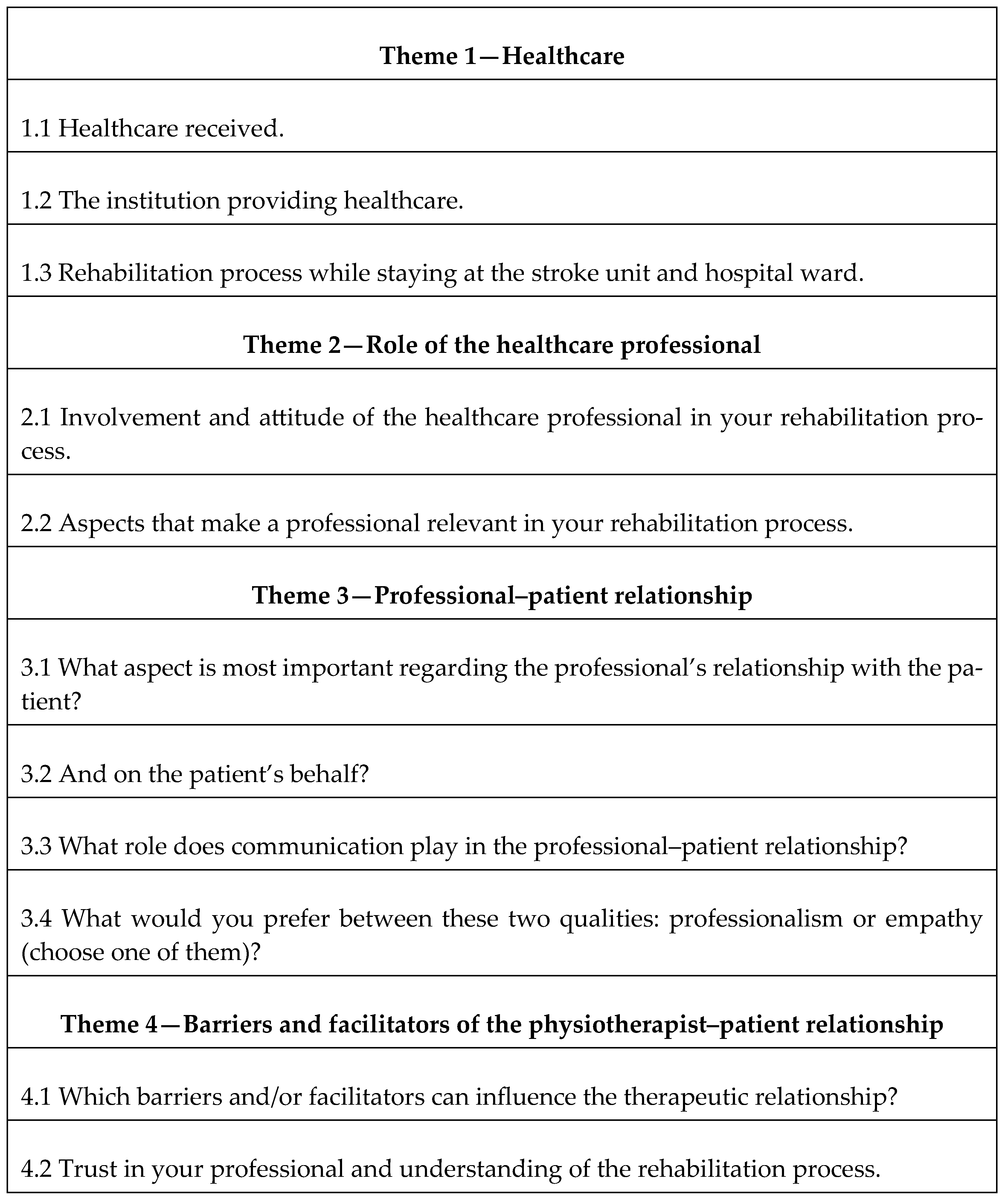

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample/Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analysis of the Results

2.5. Ethical Issues/Statement

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Healthcare

3.1.1. Subtheme 1.1: Healthcare Received

‘On 9 March I started with a loss of strength in my right arm and was diagnosed with an anxiety attack. I went home and in a couple of days I felt worse and ended up in the emergency room of the XX hospital where they determined that I had suffered a stroke. I was admitted to the stroke unit for 4 days, but when I left everything was complicated by a compartment syndrome, due to a hematoma, which meant that everything was paralyzed, and I went back to the operating theatre. I only had therapy for the first week because it stopped due to the operation. The total stay in the XX was one month.’ (P 3).

‘After a month I was referred to the XX clinic (medium stay brain damage) in mid-April. There I had physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and neuropsychology from Monday to Friday (as it was a service provided by the health service of her autonomous community). After two months, I was transferred to an outpatient regime, with two hours a day of therapy, one of physiotherapy and the other shared with the rest of the professionals.’ (P 10).

‘My accident happened in August, and I was admitted to the ICU for a couple of days until it stabilized. During that time nobody came to give me rehabilitation. I only had (occasional) contact with nurses and once a day the doctor came. Then I went up to the ward and was admitted to hospital X for 30 days. I can say that they didn’t pay any attention to what I asked for (a lot of pain in my shoulder and sacrum, and the nurses told me to put up with it). In all that time the physio only came up one day, and all he did was move my arms and legs. I told him that my shoulder was hurting, and asked if he could help me, however he just left.

‘A couple of days before I was discharged (and without knowing what would become of me because I could not fend for myself), they told me that they would talk to a center in X (a city in the same autonomous community, although very far away) to assess me and see if I was a candidate for treatment at that center. What a horrible day I had! They hurt me a lot and I could see that their assessment was ridiculous. Before we left (all the professionals who were there assessed me in an hour and a half), they told me (both my family and myself) that there was no solution and that from now on I should ‘fend for myself’. I’m honestly not lying. What I am telling you can be confirmed by my husband, my sister and my son, who were present.’ (P 22).

3.1.2. Subtheme 1.2 and 1.3: The Institution Providing Healthcare and Rehabilitation Process During Their Stay

‘Initially I was referred to the XX (public hospital) for a month. I only had physiotherapy, but very little. Then I was at the XX hospital (public half-stay hospital) for 3 months, with daily intensive treatment, receiving physio and occupational therapy. Then I went to Ceadac (a public non-health center specialized in neurological damage) for 7 months, and I ended up at XX (private center) since October 2019.’ (P 6).

‘It hit me at home at night, and I fell to the floor. I arrived at the hospital by ambulance, they did tests in the emergency room. The treatment was fantastic (the hospital is in the north of Spain). I was not in the stroke unit, and they operated on me. I spent four days in the boxes and got worse because I had another stroke. All together I was there one week and then I was discharged (even though my left side was paralyzed).

In occupational therapy I did make progress (received after physiotherapy). There, I really did improve. Thanks to a relative, I got to know a private neurological center.’ (P 19).

3.2. Theme 2: Role of Health Professionals

3.2.1. Subtheme 2.1: Involvement and Attitude of the Healthcare Professional

3.2.2. Subtheme 2.2: Aspects That Make a Professional Relevant in Your Rehabilitation Process

3.3. Theme 3: Professional-Patient Relationship

3.3.1. Subtheme 3.1 and 3.2: Professional Relationship with the Patient

3.3.2. Subtheme 3.3: Communication

3.3.3. Subtheme 3.4: Professionalism or Empathy

3.4. Theme 4: Barriers and Facilitators of the Physiotherapist–Patient Relationship

4. Discussion

- -

- Healthcare:

- -

- Care provided by health professionals

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COREQ | Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| ABI | Acquired Brain Injury |

| SU | Stroke Units |

| ICUs | Intensive Care Units |

References

- Informe Sanitario Sistema Nacional de Salud Gobierno de España. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/tablasEstadisticas/InfAnualSNS2023/INFORME_ANUAL_2023.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Abordaje del Accidente Cerebrovascular [Internet]. Madrid: Sistema Nacional de Salud. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/docs/200204_1.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Díaz-Guzmán, J.; Egido, J.A.; Gabriel-Sánchez, R.; Barberá-Comes, G.; Fuentes-Gimeno, B.; Fernández-Pérez, C. IBERICTUS Study Investigators of the Stroke Project of the Spanish Cerebrovascular Diseases Study Group. Stroke and transient ischemic attack incidence rate in Spain: The IBERICTUS study. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2012, 34, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Guzmán, J.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Benito-León, J.; Vega, S.; Gabriel, R.; Medrano, M.J.; Neurological Disorders in Central Spain (NEDICES) Study Group. Prevalence of stroke and transient ischemic attack in three elderly populations of central Spain. Neuroepidemiology 2008, 30, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vloothuis, J.D.; Mulder, M.; Veerbeek, J.M.; Konijnenbelt, M.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Ket, J.C.; Kwakkel, G.; van Wegen, E.E. Caregiver-mediated exercises for improving outcomes after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 21, CD011058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cuadrado, Á.A. Rehabilitación del ACV: Evaluación, pronóstico y tratamiento. Galicia Clínica 2009, 70, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- AVERT Trial Collaboration Group. Efficacy and safety of very early mobilisation within 24 h of stroke onset (AVERT): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 46–55, Erratum in Lancet 2015, 386, 30; Erratum in Lancet 2017, 389, 1884. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhorne, P.; Stott, D.J.; Robertson, L.; MacDonald, J.; Jones, L.; McAlpine, C.; Dick, F.; Taylor, G.S.; Murray, G. Medical complications after stroke: A multicenter study. Stroke 2000, 31, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasell, R.W.; Foley, N.C.; Bhogal, S.K.; Speechley, M.R. An evidence-based review of stroke rehabilitation. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2003, 10, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musicco, M.; Emberti, L.; Nappi, G.; Caltagirone, C. Italian Multicenter Study on Outcomes of Rehabilitation of Neurological Patients. Early and long-term outcome of rehabilitation in stroke patients: The role of patient characteristics, time of initiation, and duration of interventions. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 84, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risedal, A.; Zeng, J.; Johansson, B.B. Early training may exacerbate brain damage after focal brain ischemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 1999, 19, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, E.R.; Moudgal, R.; Lang, K.; Hyacinth, H.I.; Awosika, O.O.; Kissela, B.M.; Feng, W. Early Rehabilitation After Stroke: A Narrative Review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Estrategia en Ictus del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Available online: http://www.semg.es/doc/documentos_SEMG/estrategias_ictus_SNS.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2019).

- Álvarez-Sabín, J.; Quintana, M.; Masjuan, J.; Oliva-Moreno, J.; Mar, J.; Gonzalez-Rojas, N.; Becerra, V.; Torres, C.; Yebenes, M.; CONOCES Investigators Group. Economic impact of patients admitted to stroke units in Spain. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2017, 18, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norrving, B.; Barrick, J.; Davalos, A.; Dichgans, M.; Cordonnier, C.; Guekht, A.; Kutluk, K.; Mikulik, R.; Wardlaw, J.; Richard, E.; et al. Action Plan for Stroke in Europe 2018–2030. Eur. Stroke J. 2018, 3, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Masjuan, J.; Álvarez-Sabín, J.; Arenillas, J.; Calleja, S.; Castillo, J.; Dávalos, A.; Tejedor, E.D.; Freijo, M.; Gil-Núñez, A.; Fernández, J.L.; et al. Plan de asistencia sanitaria al ICTUS II. 2010. Neurología 2011, 26, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.L.; Vallejo, J.M.; Lara, J.A.; González, M.B.; Paniagua, E.B.; Naranjo, I.C.; Arbona, E.D.; Soriano, B.E.; Guerrero, M.F.; Fuentes, B.; et al. Análisis de recursos asistenciales para el ictus en España en 2012: ¿beneficios de la Estrategia del Ictus del Sistema Nacional de Salud? Neurología 2014, 29, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinsen, R.; Kirkevold, M.; Sveen, U. Young and midlife stroke survivors’ experiences with the health services and long-term follow-up needs. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2015, 47, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Saydah, H.; Turabi, R.; Sackley, C.; Moffatt, F. Stroke Survivor’s Satisfaction and Experience with Rehabilitation Services: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tholin, H.; Forsberg, A. Satisfaction with care and rehabilitation among people with stroke, from hospital to community care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 28, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pindus, D.M.; Mullis, R.; Lim, L.; Wellwood, I.; Rundell, A.V.; Abd Aziz, N.A.; Mant, J. Stroke survivors’ and informal caregivers’ experiences of primary care and community healthcare services—A systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192533, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adams, H.P., Jr.; Del Zoppo, G.; Alberts, M.J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Brass, L.; Furlan, A.; Grubb, R.L.; Higashida, R.T.; Jauch, E.C.; Kidwell, C.; et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2007, 38, 1655–1711, Erratum in Stroke 2007, 38, e38; Erratum in Stroke 2007, 38, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, J.; Ormston, R.; McNaughton Nicholls, C.; Lewis, J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garay Sánchez, A.; Marcén Román, Y. La importancia de la fisioterapia en el ictus. Fisioterapia 2015, 37, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Roy, M.; Rubio-Domínguez, J. Actividad asistencial y factores diferenciadores de las Unidades de Fisioterapia de un Área Sanitaria. Fisioterapia 2015, 37, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbolt, A.K.; Stenberg, M.; Lindgren, M.; Ulfarsson, T.; Lannsjö, M.; Stålnacke, B.M.; Borg, J.; DeBoussard, C.N. Associations between care pathways and outcome 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015, 30, E41–E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andelic, N.; Bautz-Holter, E.; Ronning, P.; Olafsen, K.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Schanke, A.K.; Sveen, U.; Tornas, S.; Sandhaug, M.; Roe, C. Does an early onset and continuous chain of rehabilitation improve the long-term functional outcome of patients with severe traumatic brain injury? J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekman, I.; Swedberg, K.; Taft, C.; Lindseth, A.; Norberg, A.; Brink, E.; Carlsson, J.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Johansson, I.L.; Kjellgren, K.; et al. Person-centered care--ready for prime time. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2011, 10, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten, N.; Ekman, I.; Naldemirci, Ö.; Javinger, M.; Hedman, H.; Wolf, A. Learning from Gothenburg model of person cent red healthcare. BMJ 2020, 370, m2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guía Europea de Recomendaciones Para el Tratamiento del Ictus de la European Stroke Organization (ESO). Available online: https://eso-stroke.org/wp-content/uploads/ESO08_Guidelines_Spanish.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Duncan, P.W.; Bushnell, C.; Sissine, M.; Coleman, S.; Lutz, B.J.; Johnson, A.M.; Radman, M.; Pvru Bettger, J.; Zorowitz, R.D.; Stein, J. Comprehensive Stroke Care and Outcomes: Time for a Paradigm Shift. Stroke 2021, 52, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Wu, M.; Xu, L.; Guo, Z.; Chen, S.; Ling, K.; Li, H.; Yu, X.; Zhu, X. Challenges in Accessing Community-Based Rehabilitation and Long-Term Care for Older Adult Stroke Survivors and Their Caregivers: A Qualitative Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 4829–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garnett, A.; Ploeg, J.; Markle-Reid, M.; Strachan, P.H. Factors impacting the access and use of formal health and social services by caregivers of stroke survivors: An interpretive description study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ayaz, M.; Sarwar, H.; Yaqoob, A.; Khan, M.A. Enhancing knowledge of family caregivers and quality of life of patients with ischemic stroke. Pak. J. Neurol. Surg. 2021, 25, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez-de la Cruz, S. Patients’ Experiences of the Treatment Received During Their Stay in the Stroke Unit at Spanish Healthcare Centers: A Qualitative Approach. Medicina 2025, 61, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071185

Pérez-de la Cruz S. Patients’ Experiences of the Treatment Received During Their Stay in the Stroke Unit at Spanish Healthcare Centers: A Qualitative Approach. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071185

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez-de la Cruz, Sagrario. 2025. "Patients’ Experiences of the Treatment Received During Their Stay in the Stroke Unit at Spanish Healthcare Centers: A Qualitative Approach" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071185

APA StylePérez-de la Cruz, S. (2025). Patients’ Experiences of the Treatment Received During Their Stay in the Stroke Unit at Spanish Healthcare Centers: A Qualitative Approach. Medicina, 61(7), 1185. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071185