Integrated Hospital–Territory Organizational Models and the Role of Family and Community Nurses in the Management of Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- What models of integrated hospital-to-community care are used for the management of chronic conditions with nursing involvement?

- -

- What is the role of the family and community nurse within these organizational models?

- -

- What outcomes (clinical, organizational, economic, or experiential) are associated with such models?

- -

- What barriers and facilitators influence the implementation of these models?

- -

- Population: Nurses who work in community contexts or in integrated care settings, including family and community nurses.

- -

- Concept: Organizational models for the management of chronic conditions that include an active role of nursing care.

- -

- Context: Any health system, national or local, with no geographical restrictions.

2.1. Databases Used and Search Strategy

2.2. Data Extraction

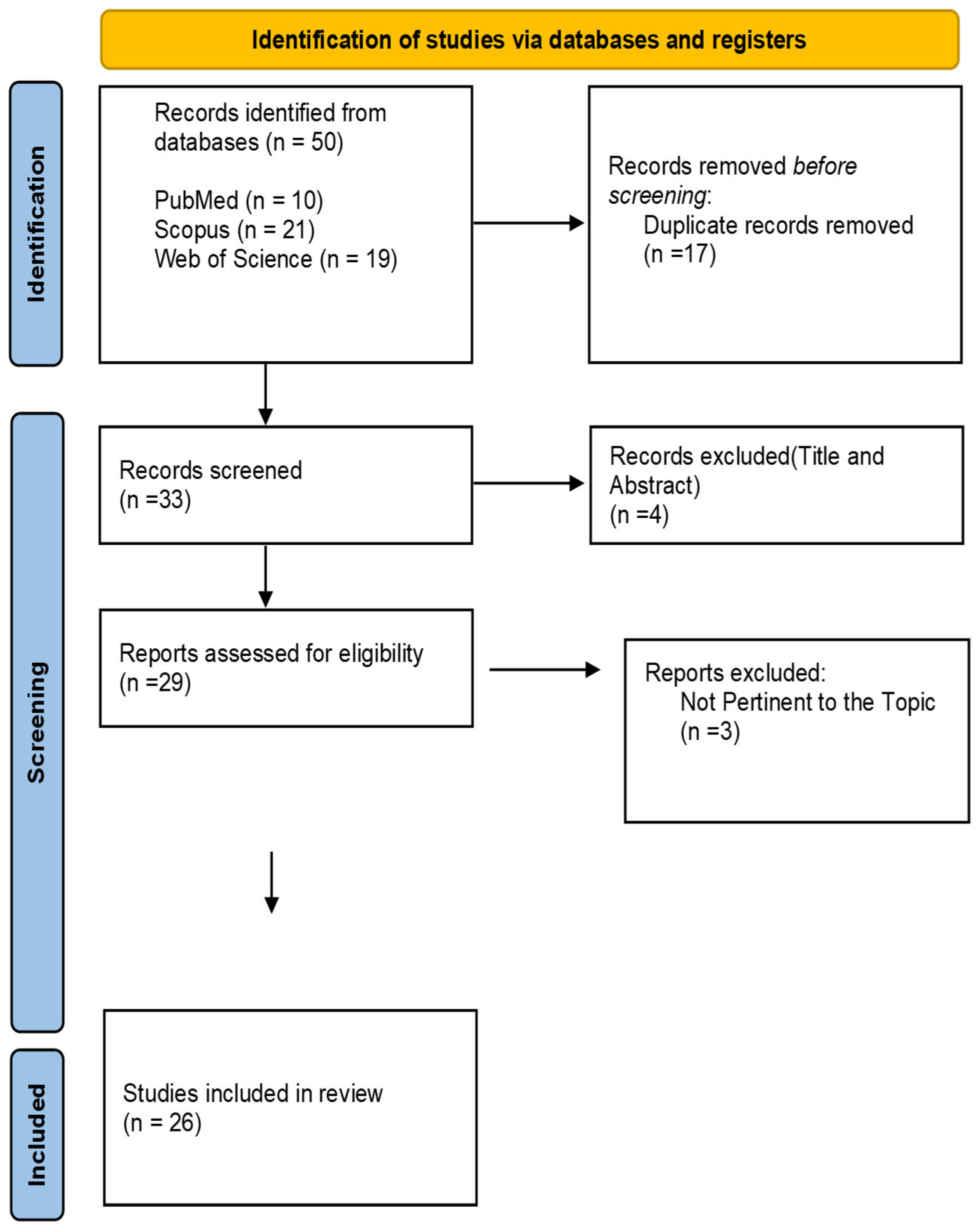

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Screening Process

2.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Main Results

- Integrated organizational models

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Role of the Community/Family Nurse

- Clinical, organizational, and subjective outcomes

- Barriers and Facilitators

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

4.2. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Endalamaw, A.; Zewdie, A.; Wolka, E.; Assefa, Y. Care models for individuals with chronic multimorbidity: Lessons for low- and middle-income countries. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, P.; Pickard, S.; Sheaff, R.; Boaden, R. Patient and carer perceptions of case management for long-term conditions. Health Soc. Care Community 2007, 15, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraeder, K.; Dimitropoulos, G.; McBrien, K.; Li, J.; Samuel, S. Perspectives from primary health care providers on their roles for supporting adolescents and young adults transitioning from pediatric services. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruikes, F.; Zuidema, S.; Akkermans, R.; Assendelft, W.; Schers, H.; Koopmans, R. Multicomponent Program to Reduce Functional Decline in Frail Elderly People: A Cluster Controlled Trial. J. Am. BOARD Fam. Med. 2016, 29, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, A.; Taylor, S.; Taylor, R.; Khan, F.; Krum, H.; Underwood, M. Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 9, CD002752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Understanding Nurse-led Case Management in Patients with Chronic Illnesses: A Realist Review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzellino, G.; De Martinis, M. Territorial reorganization, telemedicine and operative centres: Challenges and opportunities for the nursing profession. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 33, 4518–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzellino, G.; Aitella, E.; Ginaldi, L.; Vagnarelli, P.; De Martinis, M. Use of Digital and Telemedicine Tools for Postoperative Pain Management at Home: A Scoping Review of Health Professionals’ Roles and Clinical Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzellino, G.; Aitella, E.; Passamonti, M.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Protected discharge and combined interventions: A viable path to reduce hospital readmissions. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrimaglia, S.; Ricci, M.; Masini, A.; Montalti, M.; Conti, A.; Camedda, C.; Panella, M.; Dallolio, L.; Longobucco, Y. The Role of Family or Community Nurse in Dealing with Frail and Chronic Patients in Italy: A Scoping Review. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, G.; Renzi, E.; Longobucco, Y.; Cianciulli, A.; Rosso, A.; Marzuillo, C.; De Vito, C.; Villari, P.; Massimi, A. State of the Art on Family and Community Health Nursing International Theories, Models and Frameworks: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijten, F.R.M.; Struckmann, V.; van Ginneken, E.; Czypionka, T.; Kraus, M.; Reiss, M.; Tsiachristas, A.; Boland, M.; de Bont, A.; Bal, R.; et al. The SELFIE framework for integrated care for multi-morbidity: Development and description. Health Policy Amst. Neth. 2018, 122, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudin, J.; Chouinard, M.-C.; Hudon, É.; Hudon, C. Factors and Strategies Influencing Integrated Self-Management Support for People with Chronic Diseases and Common Mental Disorders: A Qualitative Study of Canadian Primary Care Nurses’ Experience. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025; epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirey, M.; Selleck, C.; White-Williams, C.; Talley, M.; Harper, D. Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Model to Advance Population Health. Popul. Health Manag. 2021, 24, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koontalay, A.; Botti, M.; Hutchinson, A. Development of a User-Centred Chronic Care Model for Patients with Heart Failure in a Limited-Resource Setting: A Codesign Study. Health Expect. 2025, 28, e70142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschodt, M.; Laurent, G.; Cornelissen, L.; Yip, O.; Zúñiga, F.; Denhaerynck, K.; Briel, M.; Karabegovic, A.; De Geest, S.; Blozik, E.; et al. Core components and impact of nurse-led integrated care models for home-dwelling older people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 105, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.; Ramsey, I.; Sharplin, G.; Eckert, M.; Shakib, S. A nurse-led, telehealth transitional care intervention for people with multimorbidity: A feasibility study. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 41, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepma, P.; Latour, C.H.M.; ten Barge, I.H.J.; Verweij, L.; Peters, R.J.G.; Scholte op Reimer, W.J.M.; Buurman, B.M. Experiences of frail older cardiac patients with a nurse-coordinated transitional care intervention-a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynia, K.; Uittenbroek, R.J.; van der Mei, S.F.; Slotman, K.; Reijneveld, S.A. Experiences of case managers in providing person-centered and integrated care based on the Chronic Care Model: A qualitative study on embrace. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armold, S. Utilization of the Health Care System of Community Case Management Patients. Prof. CASE Manag. 2017, 22, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Eckert, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Harmon, J.; Sharplin, G.; Shakib, S.; Caughey, G. Continuity of care for people with multimorbidity: The development of a model for a nurse-led care coordination service. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 37, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.K.Y.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Chan, T.M.F.; Chung, L.Y.F.; Chang, K.K.P.; Lee, R.P.L. Community nursing services for postdischarge chronically ill patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chow, S.K.Y.; Wong, F.K.Y. Health-related quality of life in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis: Effects of a nurse-led case management programme. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 1780–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, S.K.Y.; Wong, F.K.Y. A randomized controlled trial of a nurse-led case management programme for hospital-discharged older adults with co-morbidities. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 2257–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Eckert, M.; Shakib, S.; Harmon, J.; Hutchinson, A.; Sharplin, G.; Caughey, G. Development and Implementation of a Nurse-Led Model of Care Coordination to Provide Health-Sector Continuity of Care for People with Multimorbidity: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.; Eckert, M.; Hutchinson, A.; Harmon, J.; Sharplin, G.; Shakib, S.; Caughey, G. Effectiveness of nurse-led services for people with chronic disease in achieving an outcome of continuity of care at the primary-secondary healthcare interface: A quantitative systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 121, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsmo, A.; Løhre, A.; Røsstad, T.; Gjerde, I.; Heiberg, I.; Steinsbekk, A. Disease-specific clinical pathways-are they feasible in primary care? A mixed-methods study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2018, 36, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, C.; Sibley, J.; Palmer, J.; Phillips, A.; Willis, E.; Marshall, R.; Thompson, S.; Ward, S.; Forrest, R.; Pearson, M. Development, implementation and evaluation of nurse-led integrated, person-centred care with long-term conditions. J. Integr. CARE 2017, 25, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Mendes, D.; Caldeira, S.; Jesus, E.; Nunes, E. Nurse-led care management models for patients with multimorbidity in hospital settings: A scoping review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1960–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McParland, C.; Johnston, B.; Cooper, M. A mixed-methods systematic review of nurse-led interventions for people with multimorbidity. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3930–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, C.H.M.; van der Windt, D.A.W.M.; de Jonge, P.; Riphagen, I.I.; de Vos, R.; Huyse, F.J.; Stalman, W.A.B. Nurse-led case management for ambulatory complex patients in general health care: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 62, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Govern, E.M.; Maillart, E.; Bourgninaud, M.; Manzato, E.; Guillonnet, C.; Mochel, F.; Bourmaleau, J.; Lubetzki, C.; Baulac, M.; Roze, E. Making a ‘JUMP’ from paediatric to adult healthcare: A transitional program for young adults with chronic neurological disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 395, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.B.; Bendtsen, F.; Nørholm, V.; Brødsgaard, A.; Kimer, N. Nurse-assisted and multidisciplinary outpatient follow-up among patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0278545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraeder, C.; Fraser, C.; Clark, I.; Long, B.; Shelton, P.; Waldschmidt, V.; Kucera, C.; Lanker, W. Evaluation of a primary care nurse case management intervention for chronically ill community dwelling older people. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, A.; Petty, J. Preparing young people with complex needs and their families for transition to adult services. Nurs. Child. Young People 2019, 31, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzellino, G.; Dante, A.; Petrucci, C.; Caponnetto, V.; Aitella, E.; Lancia, L.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Intention to leave and missed nursing care: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2025, 8, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Counsell, S.R.; Callahan, C.M.; Clark, D.O.; Tu, W.; Buttar, A.B.; Stump, T.E.; Ricketts, G.D. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007, 298, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suijker, J.; van Rijn, M.; Buurman, B.; ter Riet, G.; van Charante, E.; de Rooij, S. Effects of Nurse-Led Multifactorial Care to Prevent Disability in Community-Living Older People: Cluster Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, L.; Naef, R.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Schwarz, J.; Mahrer-Imhof, R. Effects of an advanced practice nurse in-home health consultation program for community-dwelling persons aged 80 and older. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 2223–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stijnen, M.M.N.; Jansen, M.W.J.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M.; Duimel-Peeters, I.G.P. Development of a home visitation programme for the early detection of health problems in potentially frail community-dwelling older people by general practices. Eur. J. Ageing 2013, 10, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boult, C.; Reider, L.; Leff, B.; Frick, K.D.; Boyd, C.M.; Wolff, J.L.; Frey, K.; Karm, L.; Wegener, S.T.; Mroz, T.; et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: Results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, M.; Hirschman, K.; Toles, M.; Jarrín, O.; Shaid, E.; Pauly, M. Adaptations of the evidence-based Transitional Care Model in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 213, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, T.L.; Falbo, K.J.; Phelan, H.; Gravely, A.; Krebs, E.E.; Finn, J.A.; Matsumoto, M.; Muschler, K.; Olney, C.M.; Kiecker, J.; et al. Clinician perspectives on postamputation pain assessment and rehabilitation interventions. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2024, 48, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, M.; Oddone, E.Z.; Henderson, W.G. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morilla-Herrera, J.C.; Garcia-Mayor, S.; Martín-Santos, F.J.; Kaknani Uttumchandani, S.; Leon Campos, Á.; Caro Bautista, J.; Morales-Asencio, J.M. A systematic review of the effectiveness and roles of advanced practice nursing in older people. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/ Year | Main Theme | Geographical Context | Study Type | Sample/Population | Key Findings | Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endalamaw et al., 2024 [1] | Mapping care models for chronic multimorbidity, with a focus on their components, impacts, implementation barriers, and facilitators, especially relevant for low- and middle-income countries | Multinational | Scoping review | 54 studies addressing care models for adults with chronic multimorbidity; models covered included integrated, collaborative, nurse-led, chronic, and geriatric models, among others | Care models have been implemented to improve patient satisfaction, cost efficiency, health outcomes, and the overall quality of care. The analysis highlighted several key elements, including multidisciplinary teams, personalized care plans, follow-up, the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), the involvement of patients and caregivers, leadership, and funding structures. Some critical issues emerged, such as limited resources, team coordination, communication, and access to technology. Among the models analyzed, nurse-led and integrated models proved to be effective and adaptable to various care settings. | Few studies conducted in low-income countries; limited evidence on implementation feasibility in resource-constrained contexts; lack of standardized evaluation tools; need for culturally adapted models and further testing of models in diverse healthcare systems. |

| Sargent et al., 2007 [2] | Understanding patient and carer perspectives on nurse-led case management for long-term conditions in community settings | United Kingdom | Qualitative study | 72 patients and 52 carers receiving community matron case management across six Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) | Five key areas were identified in care delivery based on the principles of case management: (1) clinical care, (2) care coordination, (3) health education, (4) advocacy, and (5) psychosocial support. Patients and caregivers assigned equal importance to psychosocial support and clinical care, often describing “community matrons” as the only reliable source of emotional support. Their role, in terms of advocacy and psychological support, went beyond the recommendations outlined in the Department of Health guidelines. | Discrepancy between official policy definitions and real-world practice (“implementation surplus”); need for inclusion of psychosocial support as a formal competency domain; limited prior exploration of dual support role for both patients and carers in UK community case management. |

| Ruikes et al., 2016 [4] | To evaluate the effectiveness of an integrated primary care model based on multidisciplinary case management for frail older adults compared to usual care | Netherlands | Cluster controlled trial | 536 frail elderly aged ≥70 years (287 in the intervention group, 249 in the control group); identified using the EASY-Care Two-Step screening tool | The use of the CareWell program, designed for primary care targeting frail older adults, included structured interventions such as proactive care planning, case management, medication review, and multidisciplinary team meetings. However, it did not yield significant results regarding functional status (Katz-15), quality of life (EQ-5D), mental health, social functioning, hospital admissions, institutionalization, or mortality. Subgroup analyses also did not show any relevant differences. | Twelve-month duration may be insufficient to show effects; high heterogeneity and individual tailoring of interventions; need for person-centered outcome measures and further longitudinal research on frailty trajectories and timing of interventions. |

| Takeda et al., 2012 [5] | Effectiveness of different models of clinical service organization in reducing mortality and hospital readmissions among patients with chronic heart failure | Multinational | Systematic review of 25 RCTs | 5942 adult patients with chronic heart failure recently discharged from the hospital; follow-up of at least 6 months | There are three care models analyzed in patients with heart failure: case management, outpatient care, and multidisciplinary interventions. In particular, case management models that included specialist nurses, home visits, and telephone follow-ups consistently showed an association with reduced hospital readmissions and all-cause mortality. Other multidisciplinary approaches were also identified as effective in reducing readmissions. In contrast, interventions delivered exclusively in outpatient settings produced mixed results. Key and recurring components of the most effective care models included patient education, medication review, and support for self-management. | Uncertainty remains regarding the optimal components of each intervention; high heterogeneity across studies; lack of standardization in outcomes and intervention reporting; limited evidence on cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability. |

| Beaudin et al., 2025 [13] | Factors influencing the integration of self-management support by primary care nurses for patients with coexisting chronic diseases and common mental disorders, and strategies for improvement | Canada | Qualitative interpretive descriptive study | 23 primary care nurses with experience in follow-up care for patients with both chronic diseases and common mental disorders | The key determinants influencing the spread of nurse-led self-management support include clinical factors (knowledge, skills, workload, clinical tools, and attitudes), professional factors (roles, interdisciplinary collaboration, and team composition), and regulatory and functional factors (organizational culture and operational mechanisms). Potential improvement strategies include training focused on common mental health disorders, the development of appropriate clinical tools, and clinical support and coaching. All of this requires effective collaboration and cultural change. | Need for targeted training programs and standardized tools for SMS integration; lack of implementation frameworks and cultural safety considerations; future research needed on the effectiveness of digital tools and on the perspectives of other stakeholders including patients. |

| Shirey et al., 2021 [14] | Development and implementation of a nurse-led, interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) model focused on transitional care coordination and chronic disease management for underserved populations | United States | Descriptive implementation study | Uninsured and underinsured adults with diabetes (PATH clinic) and heart failure (HRTSA clinic), mainly African American and low-income, with complex chronic and behavioral health needs | The nurse-led care models analyzed and identified in the included studies showed high heterogeneity in terms of design, target populations, and implementation settings. Key components emerging from the most effective models included multidisciplinary collaboration, person-centered care planning, structured post-discharge follow-up, and support for patient self-management. Nurse-coordinated interventions were associated with improved continuity of care, higher patient satisfaction, and increased self-efficacy. Some studies highlighted a reduction in the unplanned use of healthcare services, such as hospital readmissions and emergency department visits, although with variable evidence. The effectiveness of these models was strongly influenced by contextual factors such as nursing autonomy, interprofessional integration, and system-level support. | Further research needed on scalability, sustainability, and generalizability to other populations and systems; limited empirical evidence linking IPCP to Quadruple Aim outcomes; call for rigorous mixed-methods evaluation and cost-effectiveness analysis across settings. |

| Koontalay et al., 2025 [15] | Codesign and development of a user-centered, nurse-led chronic care model for patients with heart failure in a limited-resource setting | Thailand | A codesign study | 19 participants: 1 heart failure patient, 16 clinicians (nurses, cardiologist, pharmacist, and dietitian), and 2 organizational leaders from a tertiary hospital | Nine models aimed at improving continuity of care were identified. Among them, the most effective and suitable for the management of chronic heart failure (CHF) was nurse-led case management, supported by a multidisciplinary team and characterized by strong integration with community-based services. | Need for future testing and evaluation of the prototype’s impact on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and scalability in other low- and middle-income countries; limited patient participation due to illness/readmission; potential barriers to implementation include resource constraints and hierarchical cultural norms. |

| Deschodt et al., 2020 [18] | Core components and effects of nurse-led integrated care models for home-dwelling older people | Europe, North America, New Zealand | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 19 studies, 22,168 older adults (mostly ≥65 years) living at home | Most nurse-led models were oriented toward a person-centered approach, with individualized care plans and support from multidisciplinary teams. Although many studies reported positive effects on quality of life, mortality, and hospital and emergency department access, meta-analyses did not show overall statistically significant results. | The meta-analyses did not show significant effects on outcomes. Almost no model used implementation theories to explain how the model should work. Aspects such as reimbursement, costs, and the use of technologies (e.g., telemedicine) were rarely included or described. |

| Davis et al., 2024 [19] | Feasibility of a nurse-led transitional care intervention via telehealth for adult patients with multimorbidity discharged from an acute care hospital | Australia | Feasibility study using mixed methods | 21 adult patients (mean age 78 years) with multimorbidity (3 to 10 chronic conditions), followed for 6–10 weeks post-discharge | The study analyzed a nurse-led intervention for patients with multimorbidity, focused on continuity of care and remote transitional support (telehealth). Patients reported high satisfaction, improved access to services, and a reduced perception of readmission risk. In fact, only 24% were actually readmitted. Furthermore, healthcare professionals played an active role in managing hospital flow through the presence of a Transition Coordinator. The intervention proved to be feasible, practical, and adaptable to the clinical context. | Need for a randomized controlled trial to assess effectiveness and cost-efficiency; absence of systematic hospital readmission risk assessment for patients with multimorbidity; inconsistencies in discharge handover to primary care. |

| Jepma et al., 2021 [20] | Experiences of frail older cardiac patients with a nurse-coordinated transitional care intervention (Cardiac Care Bridge) | Netherlands | Qualitative study | 16 frail cardiac patients aged ≥70 years (mean age: 82.4) who had participated in the intervention arm of a transitional care program | Study participants expressed satisfaction with the active support received through post-discharge home visits, which ensured continuity of care. However, recovery experiences varied: some reported physical improvements, while others faced difficulties due to comorbidities or frailty. Home visits conducted by the community nurse had a positive impact, although their added value is often not fully recognized. Individuals who regularly rely on formal or informal support networks tended to be skeptical about the interventions provided by professionals involved in the continuity-of-care team. | Difficulty distinguishing between usual care and the intervention; uncertainty about which patient subgroups benefit most; need to tailor interventions to frailty level, self-management abilities, and existing care networks. |

| Uittenbroek et al., 2018 [21] | Experiences and role adaptation of case managers in delivering person-centered and integrated care to older adults through the Embrace model | Netherlands | Qualitative study | 11 case managers | Case managers have shifted from a task-based model to a person-centered one, focusing on building trust-based relationships, empowerment, and patient autonomy. The main themes that emerged included a new relational approach with older patients, the introduction of new professional roles, the enhancement of skills and knowledge, and the perceived benefits resulting from case management activities. Despite the role not receiving the recognition it deserves, case managers found this position rewarding both personally and professionally. | Need for clearer support structures, integration of guidelines, and better role definition; issues with combining traditional roles and case management; the importance of continuous training and organizational backing to support long-term implementation and identity development in new care models. |

| Armold, 2017 [22] | Effectiveness of a nurse-led community case management (CCM) program in reducing healthcare utilization in chronically ill adult patients | United States | Retrospective observational study | 307 patients with at least one chronic disease; 151 accepted CCM services, 156 refused | Patients who took part in chronic care management (CCM) services experienced a 55% reduction in emergency department visits and a 61% decrease in hospital admissions compared to those who did not participate. A reduction of 47% in non-urgent visits was also observed, although it was not statistically significant. The CCM services, offered free of charge, were delivered by nurses with advanced training and a master’s degree through home visits and care coordination activities. | Lack of demographic data to identify which subgroups benefit most; limited tracking of patients who may have used other health systems or moved; further research needed on the timing and specific interventions that yield the greatest impact. |

| Davis et al., 2020 [23] | Development of a nurse-led, person-centered care coordination model to improve the continuity of care for people with multimorbidity at the primary–secondary healthcare interface | Australia | Qualitative descriptive | 44 stakeholders (nurses, physicians, allied health professionals, consumer advocates, Aboriginal representatives, executives, general practitioners, and academics) participated in forums and a validation workshop | A pragmatic and adaptable nurse-led care coordination model was designed. The model is built around a transversal component (intersectoral multidisciplinary collaboration), four domains (coordination, governance, communication, and culture), and six operational areas. It addresses existing care challenges in light of current models, integrates cultural and governance elements, ensures personalized and person-centered care, and enhances continuity of care across different healthcare settings. | The model’s feasibility and impact are yet to be evaluated in practice (to be addressed in Part 2 of the study); future studies should assess its implementation, sustainability, and effect on health outcomes; need for tools to validate stakeholder input and broader application in diverse care settings. |

| Chow et al., 2008 [24] | Evaluation of the impact of community nursing services (CNSs) on self-reported health and hospital readmission among chronically ill patients after discharge | Hong Kong, China | Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial | 46 chronically ill patients | Clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) played an important role in improving the perceived health status of patients with cardiac and respiratory conditions. However, no significant reduction in hospital readmissions was observed. The vast majority of identified issues were related to physiological factors and health-related behaviors. The most commonly adopted nursing intervention was surveillance, followed by health education activities and care procedures. For patients with respiratory conditions, greater emphasis was placed on health education. | Home visits led to significant improvements in self-reported health among patients with respiratory and cardiovascular conditions, but no statistically significant effects were found for hospital readmissions. Additionally, age, gender, and financial status were identified as predictors of self-perceived health. |

| Chow & Wong, 2010 [25] | A nurse-led case management program with motivational telephone follow-up to improve the quality of life of patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis | Hong Kong | Randomized controlled trial with pre- and post-test designs | 85 patients with end-stage renal failure (43 in the intervention group, 42 in the control) | The study found that the nurse-led case management model, followed by motivational telephone follow-ups, significantly improved the quality of life in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Improvements were noted in symptoms, the impact of kidney disease, sleep, pain, emotional well-being, social functioning, and patient satisfaction. Additional positive outcomes included perceived support from healthcare staff, sleep quality, and social functioning. However, no significant differences were observed in physical health or in the general perception of overall health status. | Generalizability limited due to recruitment from only two hospitals; control group also had access to hotline services, which may have diluted differences; further studies needed to assess long-term outcomes, cost-effectiveness, and scalability across broader renal populations. |

| Chow & Wong, 2014 [26] | Effectiveness of a nurse-led case management program using empowerment strategies to improve outcomes in older adults with multiple chronic conditions after hospital discharge | Hong Kong | Randomized controlled trial | 281 older adults | Older adults with at least two chronic conditions received case management interventions, specifically home visits and phone calls. They were randomly assigned to two intervention groups and one control group. The results showed that readmission rates in the intervention groups were significantly reduced within 84 days after discharge. Additionally, these patients reported improvements in self-efficacy, perceived health status, and physical quality of life. No significant differences were found in mental health outcomes. Key elements contributing to the success of post-discharge interventions delivered by nurse case managers included personalization, empowerment, and support for self-management. | Unclear long-term impact beyond 12 weeks; further evaluation needed for cost-effectiveness and scalability; results influenced by nurse–patient relationship and intervention fidelity; generalizability may be limited due to local context and inclusion criteria. |

| Davis et al., 2019 [27] | Design and implementation of a nurse-led model to enhance continuity of care across health sectors for individuals with multimorbidity | Australia | Mixed-methods study protocol | Patients with multimorbidity discharged from a tertiary hospital | The protocol proposes a flexible, person-centered nurse-led care coordination model. It consists of six phases: assessment during hospitalization, identification of an individualized care plan, post-discharge follow-up, communication with general practitioners, coordination of care across different healthcare settings, and evaluation. Particular emphasis is placed on multidisciplinary collaboration and the integration of governance and cultural aspects within the reference model. | As a study protocol, no clinical outcomes have yet been reported. Future work is needed to evaluate the feasibility, effectiveness, and cost-efficiency of the model in real-world practice, especially its impact on patient outcomes and health system integration. |

| Davis et al., 2021 [28] | Effectiveness of nurse-led services in achieving continuity of care for chronic disease patients across the primary–secondary healthcare interface | Multinational | Quantitative systematic review | 14 studies included with a total of 4090 adult patients (aged 29–95) with chronic diseases | Nurse-led services are associated with improved patient outcomes, such as reduced hospitalizations and readmissions, increased patient satisfaction, enhanced quality of life, better self-management, and improved symptom control. All the analyzed models included interventions that ensured continuity of care—relational, informational, and managerial—but only a few measured continuity as a specific outcome using validated tools. | Need for cost-effectiveness studies and validation of continuity measurement tools. |

| Grimsmo et al., 2018 [29] | Feasibility of implementing disease-specific clinical pathways in primary care settings, with a focus on multimorbidity and care transitions | Norway | Mixed-methods study (qualitative + quantitative) | 155 health professionals and managers in two case studies (qualitative); 214,722 adult inhabitants and 6061 home healthcare patients across four municipalities (quantitative) | The structuring of disease-specific clinical pathways is not suitable for managing chronic patients in the context of primary care. An effective approach is person-centered, using flexible and personalized care pathways based on individual needs rather than a single condition. Disease-specific pathways tend to be too complex and rigid to apply in everyday practice, especially in home care settings where time is limited and flexibility is essential. | Insufficient research on the contextual adaptation of clinical guidelines during care transitions from hospital to home. |

| Harvey et al., 2017 [30] | Design, implementation, and evaluation of a nurse-led, person-centered integrated care model for people living with long-term conditions (LTCs) | New Zealand | Implementation project with mixed-methods evaluation (qualitative, quantitative, and participatory) | Adults with LTCs, particularly those recently discharged from a hospital or newly diagnosed; focus on populations in high-deprivation areas | The model introduced the role of Liaison Nurse Consultants (LNCs) with the aim of coordinating care between primary and secondary services, thereby reducing hospital admissions. Key aspects examined included continuity of care, quality of life, equity, and health literacy. Preliminary analyses showed a reduction in hospital admissions and greater engagement within disadvantaged communities. This model highlighted the importance of cultural competence, intersectoral collaboration, and patient empowerment. | Full outcome data and long-term results pending. |

| Gonçalves et al., 2022 [31] | Mapping and classification of nurse-led care management models for hospitalized patients with multimorbidity | Multinational | Scoping review | 21 included studies | The review identified three categories of nurse-led care models: (1) nurse-led programs (such as discharge planning activities, outpatient clinics, and targeted interventions), (2) case management models (led by clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, etc.), and (3) models with nurse facilitators (e.g., nurse navigators and care coordinators). All these approaches share the goal of delivering patient-centered care, supporting transitions between care settings, and promoting self-management. However, variability was observed in terms of autonomy, roles, and competencies across the different models. | Lack of standardized definitions for nurse-led care models. Need for clarity on the roles and competencies required. |

| McParland et al., 2022 [32] | Identification and evaluation of nurse-led interventions for people with multimorbidity, and the outcomes these interventions impact | Multinational | Mixed-methods systematic review | 20 studies | Most of the interventions reviewed included case management or transitional care models, all led by nurses with advanced competencies. Common features identified included support for self-management, person-centered care planning, and continuity of care. Positive effects were most evident in patient-reported outcomes, such as perceived quality of care, health-related quality of life, and self-efficacy. However, the impact on healthcare service use, costs, and mortality proved to be more variable. | Few studies used standardized definitions or validated tools for continuity and multimorbidity; more robust evaluations needed to assess long-term and cost-related outcomes. |

| Latour et al., 2007 [33] | Effectiveness of nurse-led case management for complex ambulatory patients in general health care | Multinational | Systematic review | Ambulatory adults (≥18 years) with complex needs (e.g., multimorbidity, psychiatric comorbidity, and social vulnerabilities), not disease-specific | Post-discharge nursing case management shows - Positive effects on patient satisfaction; - No impact on emergency room visits; - Contrasting results on other clinical outcomes. | Greater clarity is needed in the definitions of “complex patient” and in the standardized evaluation of outcomes. High-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary, with sufficiently long follow-up periods and precise indicators of patient complexity. |

| McGovern et al., 2018 [34] | Evaluation of a multidisciplinary, nurse-led transitional care program (JUMP) for young adults with chronic neurological conditions moving from pediatric to adult healthcare | France | Descriptive observational study with quantitative outcome assessment (satisfaction survey) | 111 patients | In relation to the transition processes of patients with chronic neurological conditions, high levels of satisfaction were reported by both patients (89%) and parents (91%). Key factors contributing to these outcomes included a personalized and multidisciplinary approach, along with the role of Coordination Nurse Specialists (CoNSs), who ensured continuity of care by supporting patients before, during, and after the transition. | Limited generalizability due to single-center design; lack of long-term outcome data; response rate of 48% may bias results; further evaluation needed on adherence, quality of life, and engagement post-transition. |

| O’Connell et al., 2023 [35] | Assessment of the effects of nurse-assisted and multidisciplinary outpatient follow-up interventions for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis | Multinational (16 studies from Europe, Asia, the USA, and Australia) | Systematic review | 1224 adult patients; 16 included studies | Three main types of interventions were identified: (1) Educational interventions; (2) Nurse-led case management; (3) Standardized hospital follow-up. All these approaches demonstrated at least one improvement in various outcomes, such as reduced mortality, decreased readmissions, increased knowledge, greater self-efficacy, and improved quality of life. In some cases, a favorable cost-effectiveness ratio was also observed. However, none of these models proved to be superior to the others. | Significant heterogeneity across interventions and outcomes; most studies had moderate-to-low methodological quality; need for well-designed RCTs to evaluate real-world effectiveness, especially in personalized nurse-led models for liver disease. |

| Schraeder et al., 2008 [36] | Effectiveness of a collaborative nurse-led case management model in reducing healthcare utilization and costs for chronically ill older adults in primary care | United States | Non-randomized controlled trial | 677 community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 years at high risk for mortality, functional decline, or high healthcare use (400 in intervention group, 277 in control) | The integration of nurse case managers into primary care for frail older adults significantly reduced the risk of rehospitalization among hospitalized patients, improved continuity of care, and contributed to a modest reduction in overall healthcare costs. | Generalizability is limited due to regional scope; non-randomized design may introduce bias; future studies should include broader populations, randomized designs, and long-term outcome evaluations to confirm sustainability and effectiveness. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azzellino, G.; Vagnarelli, P.; Passamonti, M.; Mengoli, L.; Ginaldi, L.; De Martinis, M. Integrated Hospital–Territory Organizational Models and the Role of Family and Community Nurses in the Management of Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071175

Azzellino G, Vagnarelli P, Passamonti M, Mengoli L, Ginaldi L, De Martinis M. Integrated Hospital–Territory Organizational Models and the Role of Family and Community Nurses in the Management of Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071175

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzzellino, Gianluca, Patrizia Vagnarelli, Mauro Passamonti, Luca Mengoli, Lia Ginaldi, and Massimo De Martinis. 2025. "Integrated Hospital–Territory Organizational Models and the Role of Family and Community Nurses in the Management of Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071175

APA StyleAzzellino, G., Vagnarelli, P., Passamonti, M., Mengoli, L., Ginaldi, L., & De Martinis, M. (2025). Integrated Hospital–Territory Organizational Models and the Role of Family and Community Nurses in the Management of Chronic Conditions: A Scoping Review. Medicina, 61(7), 1175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071175