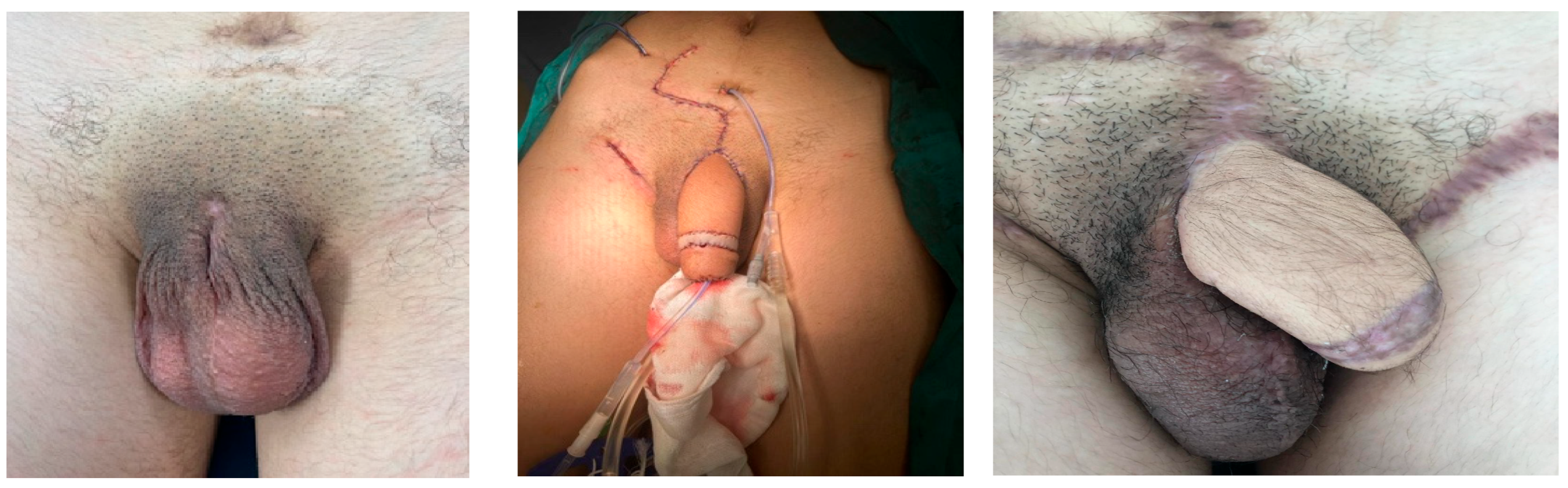

Phalloplasty in Children with Severe Penile Tissue Loss: Single Center Case Series

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ochoa, B. Trauma of the external genitalia in children: Amputation of the penis and emasculation. J. Urol. 1998, 160, 1116–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bahnasawy, M.S.; El-Sherbiny, M.T. Paediatric penile trauma. BJU Int. 2002, 90, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amukele, S.A.; Lee, G.W.; Stock, J.A.; Hanna, M.K. 20-year experience with iatrogenic penile injury. J. Urol. 2003, 170, 1691–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gearhart, J.P.; Rock, J.A. Total ablation of the penis after circumcision with electrocautery: A method of management and long-term followup. J. Urol. 1989, 142, 799–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertoy, A.; Tiryaki, H.T.; Şenel, E.; Demirtas, G.; Yayla, D.; Tagci, S. A rare complication of circumcision due to monopolar cauterization: Penile necrosis. Pediatr. Urol. Case Rep. 2021, 8, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, G.R.; Stoller, M.L.; Jacobs, M.M.; Kogan, B.A. Newborn penile glans amputation during circumcision and successful reattachment. J. Urol. 1995, 153, 778–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.K.; Min, J.K.; Kim, H.J. Reimplantation of an amputated penis in prepubertal boys. J. Urol. 2001, 165, 586–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezior, J.R.; Brady, J.D.; Schlossberg, S.M. Management of penile amputation injuries. World J. Surg. 2001, 25, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retik, A.B.; Keating, M.; Mandell, J. Complications of hypospadias repair. Urol. Clin. N. Am. 1988, 15, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoha, C.G.; Shu’aibu, S.I.; Akpayak, I.C.; Dakum, N.K.; Ramyil, V.M. Male external genital injuries; pattern of presentation and management at the Jos University Teaching Hospital. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2014, 13, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, J.T.; Bjurlin, M.A.; Cheng, E.Y. Pediatric genital injury: An analysis of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Urology 2013, 82, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hage, J.J.; De Graaf, F.H. Addressing the ideal requirements by free flap phalloplasty: Some reflections on refinements of technique. Microsurgery 1993, 14, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoriaty, N.; Schick, E. Penile gangrene: An unusual complication of priapism. How to avoid it? Urology 1980, 16, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.B.; Sadove, A.M.; Rink, R.C. Reconstruction after total penile amputation and emasculation. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2003, 50, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beniamin, F.; Castagnetti, M.; Rigamonti, W. Surgical management of penile amputation in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 1939–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cezarino, B.N.; Arceo, R.; Leslie, J.A.; Koyle, M.; Dénes, F.T.; Prieto, J. Scrotal flap phalloplasty as temporary neophallus in infants and children with penile agenesis: Multi-institutional experience and long-term follow-up. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaffa, G.; Raheem, A.A.; Ralph, D.J. An update on penile reconstruction. Asian J. Androl. 2011, 13, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancı, A.; Gülpınar, B.; Gülpınar, Ö. Successful management of hair follicles following urethroplasty with holmium:YAG laser epilation: A case report. J. Surg. Med. 2019, 3, 817–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, D.E., Jr.; Orihuela, E.; Crotty, K.; LaHaye, M.; Davidson, S.; Motamedi, M. Laser ablation of urethral hair. Lasers Surg. Med. 1999, 24, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagario, U.G.; Piramide, F.; Pang, K.H.; Durukan, E.; Tzelves, L.; Ricapito, A.; Baekelandt, L.; Checcucci, E.; Carrion, D.M.; Bettocchi, C.; et al. Techniques for Penile Augmentation Surgery: A Systematic Review of Surgical Outcomes, Complications, and Quality of Life. Medicina 2024, 60, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardi, Y.; Har-Shai, Y.; Gil, T.; Gruenwald, I. A critical analysis of penile enhancement procedures for patients with normal penile size: Surgical techniques, success, and complications. Eur. Urol. 2008, 54, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogoraz, N.A. On complete plastic reconstruction of a penis is sufficient for coitus. Sov. Surg. 1936, 8, 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hage, J.J.; Bout, C.A.; Bloem, J.J.A.M.; Megens, J.A.J. Phalloplasty in female-to-male transsexuals: What do our patients ask for? Ann. Plast. Surg. 1993, 30, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.; Tamimy, M.S. Phalloplasty: The dream and the reality. Indian. J. Plast. Surg. 2013, 46, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puckett, C.L.; Reinisch, J.; Montie, J.E. Free flap phalloplasty. J. Urol. 1982, 128, 294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Bianchi, A. The parascrotal flap phallo-urethroplasty for aphallia reconstruction in childhood: Report of a new technique. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2014, 10, 769–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.E.; da Cruz, M.L.; Liguori, R.; Garrone, G.; Leslie, B.; Ottoni, S.L.; Souza, G.R.; Ortiz, V.; de Castro, R.; Macedo, A., Jr. Neophalloplasty in boys with aphallia: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2016, 12, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, R.; Merlini, E.; Rigamonti, W.; Macedo, A., Jr. Phalloplasty and urethroplasty in children with penile agenesis: Preliminary report. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 1112–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Cause | Type of Tissue Loss | Treatment | Continence | Cosmetic Appearance | Secondary Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | Corpus/Penile Shaft | ||||||

| 5 y | Exprophy vesica, aphallia | No cavernous tissue | Local scrotal skin flap | Scrotal flap phalloplasty | Incontinent | Poor | Bladder neck closure |

| 17 y | Trauma | Total penile amputation, no cavernous tissue | Forearm free skin flap | Microsurgical free radial forearm flap phalloplasty | Incontinent | Poor | Urethral stricture, urethroplasty, vesicostomy |

| 3 y | Monopolar cautery burn | Partial penile amputation | Local skin graft | Cavernous body dissection, | Continent | Adequate | - |

| 6 m | Monopolar cautery burn | Total penile amputation, no cavernous tissue | Local skin graft | Cavernous body dissection | Continent | Adequate | - |

| 5 y | Hypospadias surgery | Partial glans loss, penile skin loss | Local skin graft | Glans and penile skin reconstruction | Continent | Good | - |

| 8 y | Fournier gangrene (Burkitt lymphoma) | Glans loss, total penile skin loss | Local skin graft | Glans and penile skin reconstruction | Continent | Good | - |

| 6 y | Gun shot | Partial penile amputation | Local skin graft | Cavernous body dissection | Continent | Good | - |

| 5 y | Extrophy cloaca | Partially existing corpus cavernousum | Local skin graft | Cavernous body dissection | Incontinent | Poor | - |

| 2 y | Rudimentary penis | No cavernous tissue | Suprapubic skin flap | Local skin flap phalloplasty | Continent | Poor | Urethral dilatation |

| 5 y | Extrophy vesica, diphallia | Two separate cavenous tissues | Local skin graft | Excision of non-functional cavernous tissue and reconstruction with local skin graft | Continent | Excellent | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Demirtas, G.; Tagcı, S.; Yayla, D.; Ergani, H.M.; Ekberli, G.; Karabulut, B.; Tiryaki, H.T. Phalloplasty in Children with Severe Penile Tissue Loss: Single Center Case Series. Medicina 2025, 61, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071124

Demirtas G, Tagcı S, Yayla D, Ergani HM, Ekberli G, Karabulut B, Tiryaki HT. Phalloplasty in Children with Severe Penile Tissue Loss: Single Center Case Series. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071124

Chicago/Turabian StyleDemirtas, Gokhan, Suleyman Tagcı, Derya Yayla, Hasan Murat Ergani, Gunay Ekberli, Bilge Karabulut, and Huseyin Tugrul Tiryaki. 2025. "Phalloplasty in Children with Severe Penile Tissue Loss: Single Center Case Series" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071124

APA StyleDemirtas, G., Tagcı, S., Yayla, D., Ergani, H. M., Ekberli, G., Karabulut, B., & Tiryaki, H. T. (2025). Phalloplasty in Children with Severe Penile Tissue Loss: Single Center Case Series. Medicina, 61(7), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071124