Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Excision and Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect: A Scoping Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Volume Calculation (Base x Height))/2, as Simple or first degree < 15 mm2; Simple with one branch or second degree = 16–25 mm2 or Complex with more than one branch or third degree > 25 mm2.

- -

- Deficiency Ratio, the ratio between residual myometrium and healthy myometrium x 100, as Large when the thickness of the residual myometrium is <50% of the healthy myometrium or Small when the thickness of the residual myometrium is >50% of the healthy myometrium.

- -

- Measure of the minimum free myometrium, as Large if the residual myometrium is <2 mm with US, <2.5 mm with SHG, < 3 mm with MRI or Small, if the residual myometrium is >2 mm with US, > 2.5 mm with SHG, >3 mm with MRI.

- -

- Shape (triangle, semicircle, rectangle, circular, drop, inclusion cyst) [2].

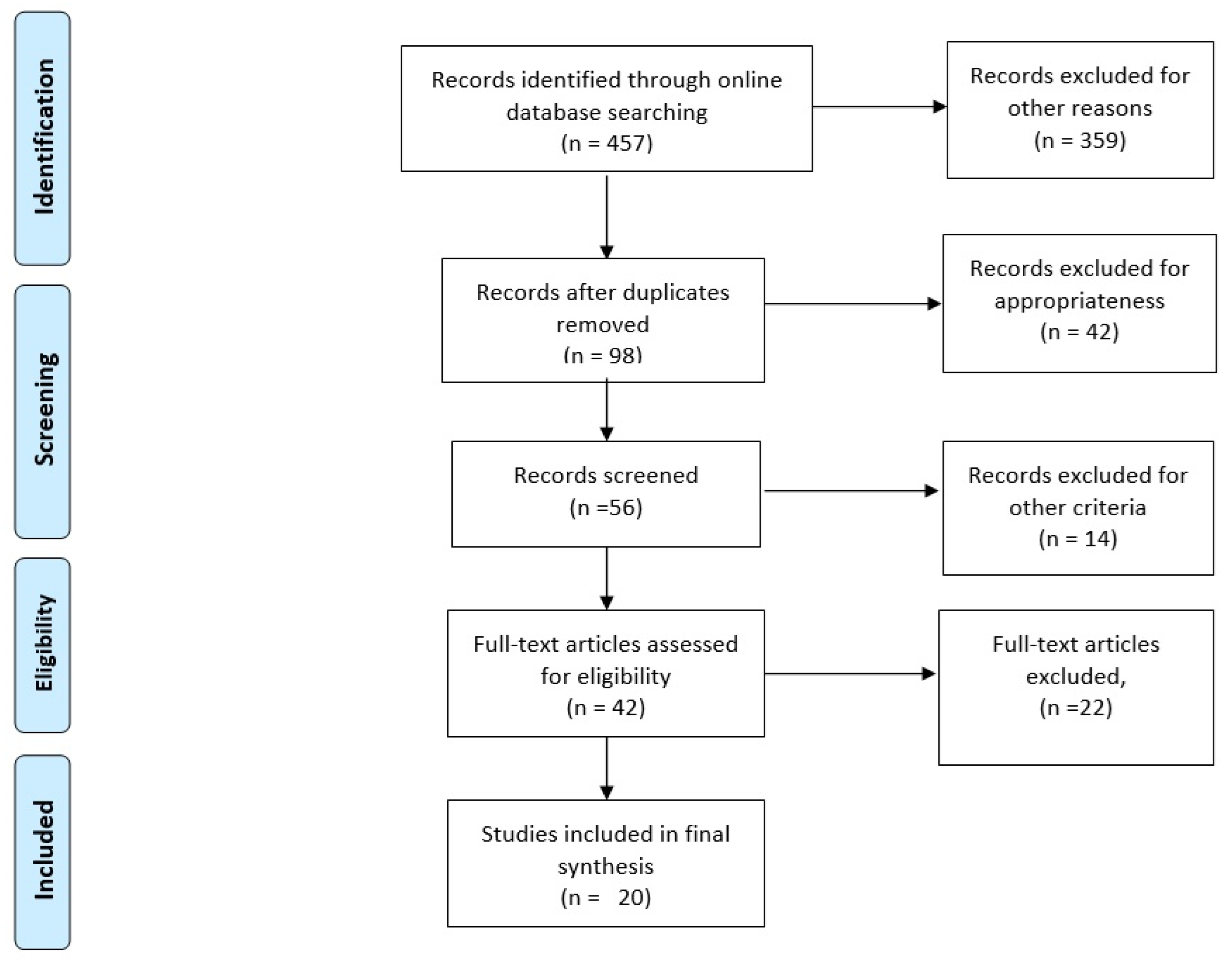

2. Methods

Relevant Sections

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dominguez, J.A.; Pacheco, L.A.; Moratalla, E.; Carugno, J.A.; Carrera, M.; Perez-Milan, F.; Caballero, M.; Alcázar, J.L. Diagnosis and management of isthmocele (Cesarean scar defect): A SWOT analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 62, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremer, T.G.; Ghiorzi, I.B.; Dibi, R.P. Isthmocele: An overview of diagnosis and treatment. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. (1992) 2019, 65, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bij de Vaate, A.J.M.; Br ¨olmann, H.A.; van der Voet, L.F.; van der Slikke, J.W.; Veersema, S.; Huirne, J.A. Ultrasound evaluation of the Cesarean scar: Relation between a niche andpostmenstrual spotting. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 37, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordans, I.P.M.; de Leeuw, R.A.; Stegwee, S.I.; Amso, N.N.; Barri-Soldevila, P.N.; van den Bosch, T.; Bourne, T.; Brölmann, H.A.M.; Donnez, O.; Dueholm, M.; et al. Sonographic examination of uterine isthmocele in non-pregnant women: A modified Delphi procedure. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 53, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordans, I.P.M.; Verberkt, C.; De Leeuw, R.A.; Bilardo, C.M.; Van Den Bosch, T.; Bourne, T.; Brölmann, H.A.M.; Dueholm, M.; Hehenkamp, W.J.K.; Jastrow, N.; et al. Definition and sonographic reporting system for Cesarean scar pregnancy in early gestation: Modified Delphi method. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 59, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, S.G.; Ludwin, A.; Vilos, G.A.; Török, P.; Tesarik, J.; Vitagliano, A.; Lasmar, R.B.; Chiofalo, B. From hysteroscopy to laparoendoscopic surgery: What is the best surgical approach for symptomatic isthmocele? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setubal, A.; Alves, J.; Osório, F.; Guerra, A.; Fernandes, R.; Albornoz, J.; Sidiroupoulou, Z. Treatment for Uterine Isthmocele, A Pouchlike Defect at the Site of a Cesarean Section Scar. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Salvador, E.; Haladjian, M.C.; Bradbury, M.; Cubo-Abert, M.; Barrachina, L.M.; Escude, E.V.; Puig, O.P.; Gil-Moreno, A. Laparoscopic Isthmocele Repair with Hysteroscopic Assistance. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreibelbis, S.; Collett, A.; Pugh, C. Techniques for robotic isthmocele resection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardaillac, C.; Salmon, C.; Vaucel, E.; Gueudry, P.; Lavoue, V.; Nyangoh Timoh, K.; Thubert, T. Robot-assisted laparoscopy repair of uterine isthmocele: A two-center observational study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 160, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Surico, D.; Vigone, A.; Mazza, M.; Osella, E.; Troìa, L.; Aquino, C.I. Firefly Imaging System in Robotic Tailored Excision and Repair of a Cesarean Scar Defect. A Video-Illustrated Case Report. p1-6. Chirurgia-5884. Chirurgia Minerva pISSN 0394-9508. Available online: https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/chirurgia/index.php (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- van Reesema, L.; Shadowen, C.; Woo, J.J. Eight steps to success: Minimally invasive surgical management of cesarean scar pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2025; Epub ahead of print, S0015-0282(25)00256-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muendane, A.; Babaei Bidhendi, A.; Imesch, P.; Witzel, I.; Betschart, C. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic niche repair (RALNR): Technique development and pregnancy-associated outcomes. J. Robot. Surg. 2025, 19, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, D.; Othieno, A.; Lehrman, E.D.; Ito, T. Repair of Isthmocele Following Embolization of Uterine Arteriovenous Malformation. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2023, 30, 948–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, Z.; Gargiulo, A. Near-infrared and hysteroscopy-guided robotic excision of uterine isthmocele with laser fiber: A novel high-precision technique. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 120, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, R.; Sasaki, K.; Miller, C.E. Laparoscopic Excision of Cesarean Scar Pregnancy with Scar Revision. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 746–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, E.; Vahanian, S.; Martinelli, V.T.; Chavez, M.; Mesbah, M.; Nezhat, F.R. Combined Medical and Minimally Invasive Robotic Surgical Approach to the Treatment and Repair of Cesarean Scar Pregnancies. JSLS 2021, 25, e2021.00039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Katebi Kashi, P.; Dengler, K.L.; Welch, E.K.; DiCarlo-Meacham, A.; Jackson, A.A.; Rose, G.S. A stepwise approach to robotic assisted excision of a cesarean scar pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2021, 64, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hofgaard, E.; Westman, K.; Brunes, M.; Bossmar, T.; Persson, J. Cesarean scar pregnancy: Reproductive outcome after robotic laparoscopic removal with simultaneous repair of the uterine defect. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 262, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.F.; Chen, H.H.; Ting, W.H.; Lu, H.F.; Lin, H.H.; Hsiao, S.M. Robotic or laparoscopic treatment of cesarean scar defects or cesarean scar pregnancies with a uterine sound guidance. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyangoh Timoh, K.; Enderle, I.; Leveque, J.; Lavoue, V. Prise en charge chirurgicale d’une rétention trophoblastique après grossesse sur cicatrice de césarienne et réparation d’une isthmocèle par cœlioscopie robot-assistée associée à l’hystéroscopie [Robotic-assisted laparoscopy using hysteroscopy treatment of a residual cesarean scar pregnancy and isthmocele]. Gynecol Obstet. Fertil Senol. 2020, 48, 460–461. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, Z.; Liu, J.; Bardawil, E.; Guan, X. Surgical Management of Cesarean Scar Defect: The Hysteroscopic-Assisted Robotic Single-Site Technique. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Gu, C.; Meng, Y. Robotic CSP Resection and Hysterotomy Repair. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2021, 28, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, A.; Crochet, P.; Agostini, A. Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Treatment of Residual Ectopic Pregnancy in a Previous Cesarean Section Scar: A Case Report. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siedhoff, M.T.; Schiff, L.D.; Moulder, J.K.; Toubia, T.; Ivester, T. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic removal of cesarean scar ectopic and hysterotomy revision. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, 681.e1–681.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.S.; Nezhat, F.R. Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Repair of a Cesarean Section Scar Defect. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2015, 22, 1135–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Rosa, M.F.; McCarthy, S.; Richter, C.; Azodi, M. Robotic repair of uterine dehiscence. JSLS 2013, 17, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yalcinkaya, T.M.; Akar, M.E.; Kammire, L.D.; Johnston-MacAnanny, E.B.; Mertz, H.L. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic repair of symptomatic cesarean scar defect: A report of two cases. J. Reprod. Med. 2011, 56, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Persson, J.; Gunnarson, G.; Lindahl, B. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery of a 12-week scar pregnancy with temporary occlusion of the uterine blood supply. J. Robot Surg. 2009, 3, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Voet, L.; Bij de Vaate, A.; Veersema, S.; Brölmann, H.A.M.; Huirne, J. Long-term complications of caesarean section. The niche in the scar: A prospective cohort study on niche prevalence and its relation to abnormal uterine bleeding. BJOG An. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampini, V.; Amadori, R.; Laudiero, L.B.; Vendola, N.; Marafon, D.P.; Gerbino, M.; Piccirillo, V.; Rizza, E.; Aquino, C.I.; Surico, D. COVID-19 seroprevalence in a group of pregnant women compared to a group of non-pregnant women. Italian J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 33, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Amadori, R.; Aquino, C.I.; Colagiorgio, S.; Osella, E.; Surico, D.; Remorgida, V. What may happen if you are pregnant during COVID-19 lockdown? A retrospective study about peripartum outcomes. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 74, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cobec, I.M.; Varzaru, V.B.; Kövendy, T.; Kuban, L.; Eftenoiu, A.E.; Moatar, A.E.; Rempen, A. External Cephalic Version-A Chance for Vaginal Delivery at Breech Presentation. Medicina 2022, 58, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamberg, C.; Hinkson, L.; Dudenhausen, J.W.; Bujak, V.; Kalache, K.D.; Henrich, W. Longitudinal transvaginal ultrasound evaluation of cesarean scar niche incidence and depth in the first two years after single- or double- layer uterotomy closure: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.sieog.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Guida-al-Counseling-Istmocele1.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Nahum, G.G.; Pham, K.Q.; Chelmow, D. Uterine Rupture in Pregnancy. Medscape Reference. Available online: http://reference.medscape.com/article/275854-overview (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Gullo, G.; Basile, G.; Cucinella, G.; Greco, M.E.; Perino, A.; Chiantera, V.; Marinelli, S. Fresh vs. frozen embryo transfer in assisted reproductive techniques: A single center retrospective cohort study and ethical-legal implications. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 6809–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etrusco, A.; Fabio, M.; Cucinella, G.; de Tommasi, O.; Guastella, E.; Buzzaccarini, G.; Gullo, G. Utero-cutaneous fistula after caesarean section delivery: Diagnosis and management of a rare complication. Prz Menopauzalny. 2022, 21, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gullo, G.; Scaglione, M.; Cucinella, G.; Perino, A.; Chiantera, V.; D’Anna, R.; Laganà, A.S.; Buzzaccarini, G. Impact of assisted reproduction techniques on the neuro-psycho-motor outcome of newborns: A critical appraisal. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 2583–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinella, G.; Gullo, G.; Etrusco, A.; Dolce, E.; Culmone, S.; Buzzaccarini, G. Early diagnosis and surgical management of heterotopic pregnancy allows us to save the intrauterine pregnancy. Prz. Menopauzalny. 2021, 20, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vitagliano, A.; Cicinelli, E.; Viganò, P.; Sorgente, G.; Nicolì, P.; Busnelli, A.; Dellino, M.; Damiani, G.R.; Gerli, S.; Favilli, A. Isthmocele, not cesarean section per se, reduces in vitro fertilization success: A systematic review and meta-analysis of over 10,000 embryo transfer cycles. Fertil Steril. 2024, 121, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemma, G.; De Franciscis, P.; Torella, M.; Narciso, G.; La Verde, M.; Morlando, M.; Cobellis, L.; Colacurci, N. Reproductive and pregnancy outcomes following embryo transfer in women with previous cesarean section: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, A.; Geiger, J.; Vinayahalingam, V.; Pape, J.; Gulz, M.; Karrer, T.; Mueller, M.D.; von Wolff, M. High live birth rates after laparoscopic isthmocele repair in infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1507482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tanos, V.; Toney, Z.A. Uterine scar rupture—Prediction, prevention, diagnosis, and management. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 59, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.F.C.; Amaral, A.; Carvalho, J.P.M.; Junior, J.D. Robotic Isthmocele Repair of a Big Cesarean Scar Defect—A Feasible Technique. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 26, S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.E.; Sasaki, K.J. Surgical Repair of the Symptomatic Isthmocele. In Atlas of Robotic, Conventional, and Single-Port Laparoscopy; Escobar, P.F., Falcone, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitas, G.; Hanker, L.; Rody, A.; Ackermann, J.; Alkatout, I. Robotic surgery in gynecology: Is the future already here? Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied. Technol. 2022, 31, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.; Mckenna, M.; Sasaki, K.; Miller, C. Robotic-assisted repair of a large isthmocele. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkegkes, I.D.; Psomiadou, V.; Minis, E.; Iavazzo, C. Robot-assisted laparoscopic repair of cesarean scar defect: A systematic review of clinical evidence. J. Robot. Surg. 2023, 17, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavridis, K.; Balafoutas, D.; Vlahos, N.; Joukhadar, R. Current surgical treatment of uterine isthmocele: An update of existing literature. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2025, 311, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libretti, A.; Surico, D.; Corsini, C.; Aquino, C.I.; Fracon, S.; Remorgida, V. YouTube™ as a Source of Information on Acupuncture for Correction of Breech Presentation. Cureus 2023, 15, e35182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Libretti, A.; Vitale, S.G.; Saponara, S.; Corsini, C.; Aquino, C.I.; Savasta, F.; Tizzoni, E.; Troìa, L.; Surico, D.; Angioni, S.; et al. Hysteroscopy in the new media: Quality and reliability analysis of hysteroscopy procedures on YouTube™. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors/Year and Type of Study | Sample and Medical Indication | Surgical Technique and Anesthesia | Gestational Age (if CSP), in Weeks | Description of the Procedure in the Article | Duration (MOT) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surico et al. [12], 2025. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Intraoperative hysteroscopy and a robotic-assisted laparoscopy with Firefly technology. General anesthesia | / | Cold scissors were used to remove the isthmocele entirely. To heal the myometrium, a double-layer interrupted Vicryl 2-0 suture was used. There were no intraoperative difficulties. | 90 min | Correction of the defect after 30 days following surgery, healthy pregnancy after 14 months of the surgery. |

| van Reesema et al. [13], 2025. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopy. General anesthesia | 6 | The tissue around the CSP was injected with 12 mL of diluted vasopressin (20 units vasopressin in 100 mL normal saline). The cervicovaginal junction was then marked by inserting an end-to-end anastomosis sizer into the patient’s vagina. The cervix was reapproximated using two layers of running 2-0 V-loc sutures on the anterior and posterior cervix, followed by modified mattress stitches at the bilateral apices using two distinct 2-0 V-loc sutures (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN). | N.A. | Correction of the defect and negative saline-infused sonography. |

| Muendane et al. [14], 2025. Cohort study- | 24 patients, Isthmocele | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic niche repair preceded by diaphanoscopy. General anesthesia | / | Vicryl 2-0 continuous non-locked suture was used for the serosal layer of the three-layer closure, while running and barbed suture (V-Loc™ 3-0) were used for the two inner layers, which contained the first half of the myometrium without endometrium, and a second outer myometrial layer. Slow-resorbable polydioxanone sutures (PDS 2-0) are used to stitch the round ligaments to the anterior uterine wall. This reduces tension on the scar and allows for an antefexed uterine position for two to three months while the wound heals. | 145 min | Widths and depths of the niches were significantly reduced (p < 0.001), with increment of the pregnancy rate. |

| Cardaillac et al. [10], 2023. Cohort study | 33 patients, Isthmocele | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. General anesthesia | / | Monopolar scissors, bipolar forceps, and gripping forceps were the tools utilized. The whole fibrotic tissue of the isthmocele was removed. The operator used either Vicryl 1 (polyglactin 910 suture, undyed braided, Ethicon) or Monocryl 0 (poliglecaprone 25 suture, undyed monofilament, Ethicon) X stitches to suture the wound. Three or six months following the procedure, an MRI or ultrasound was conducted. | 98 min | Improved myometrial thickness [mean difference 2.71; 95% CI, 1.91–3.51], p = 0.0005); improved pregnancy rate and symptoms. 51.5% of the patients stated that they would choose to have this surgery again. |

| Huang et al. [15], 2023. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (EVAC) embolization followed by robot-assisted laparoscopic technique. General anesthesia | / | EVAC image guided uterine embolization. Isthmocele and residual EVAC in the cavity are identified hysteroscopically,and defined by fluorescence transillumination. Creation of a bladder flaps and dissection of the retroperitoneal region to skeletonize uterine arteries. Vascular clamps are used to temporarily block the uterine arteries to reduce operative blood loss. The isthmocele is removed, and any remaining intracavitary EVAC is eliminated. The uterine blood flow was restored through multilayer, bidirectional hysterotomy closure and vascular clamp removal. | N.A. | Successful treatment. |

| Walker et al. [16], 2023. Video-case report- | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery, employing a carbon dioxide laser fiber, under hysteroscopy and Firefly near-infrared guidance. General anesthesia | / | Five units of vasopressin were injected into the uterus. Energy source for dissection was a 5-watt carbon dioxide laser fiber (Lumenis FiberLase). A 20-watt laser was used for the excision in the infrared/gray scale, eliminating the whole region that the Firefly had marked. A two-layer closure was used for hysterotomy: a running 2-0 PDS Stratafix (Ethicon) was placed after four mattress sutures of 2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon). The peritoneal layer was closed in a running way with 2-0 PDS Stratafix (Ethicon). A 14 French Malecot catheter (Bard) was inserted into the uterus cavity. After covering the repair region with interceed adhesion barrier (Gynecare), the process was completed. | N.A. | Improved myometrial thickness. |

| Yoon R et al. [17], 2021. Video- case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery and hysteroscopy. General anesthesia | First trimester | Diluted vasopressin, carefully applying electrosurgical energy and, a multilayer closure were used. | N.A. | Successful treatment. |

| Hoffmann et al. [18], 2021. Case series | 5 patients, Isthmocele and CSP | Combined medical and surgical approach with robotic assisted laparoscopic resection, Firefly, and hysteroscopy. General anesthesia | 6–8 | Adesiolisis and a bladder flap were performed. The ectopic pregnancy was cut off from the uterine defect using monopolar instruments. The uterine defect was subsequently transversely repaired utilizing a two-layer closure with #0 barbed suture in a continuous, non-locked method. Chromopertubation was carried out. | N.A. | Valid treatment of current ectopic pregnancy and repair of uterine defect. |

| Katebi Kashi et al. [19], 2021. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and CSP | Robotic assisted excision and hysteroscopy with metroplasty. General anesthesia | 6 | Following the failure of methotrexate therapy, the patient had a simple robotic aided excision of the CSP and a two-layer metroplasty: Step 1: Make a bladder flap; Step 2: Separate and remove CSP; Step 3: Close the hysterotomy in two layers; and Step 4: Perform a hysteroscopy. | N.A. | Valid treatment of current ectopic pregnancy and repair of uterine defect, followed by a successful pregnancy. |

| Hofgaard et al. [20], 2021. Case series | 14 patients, Isthmocele and CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopy and intraoperative occlusion of the uterine blood supply. General anesthesia | 6–13 | After the pelvic sidewalls were dissected, nine women had their distal internal iliac arteries clipped with detachable metal clips (Bulldog clips; Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany), then taken off. The myometrium surrounding the defect was removed and then readjusted in two layers using either a continuous V-Loc suture or a single 2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany). The myometrium surrounding the CSP was injected with one to three units of Vasopressin (Pitressin®; Link Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). | N.A. | Uneventful surgeries, 64% of patients conceived naturally. |

| Wang et al. [21], 2021. Case series- | 20 patients: robotic (n = 3) or conventional laparoscopic (n = 17) surgery, Isthmocele and CSP | Robotic or laparoscopic repair, and hysteroscopy. General anesthesia | N.A. | The myometrium surrounding the cervix was penetrated with diluted vasopressin. The bladder was occasionally carefully separated from the cervix using a monopolar scissor. The uterine sound (TY90, TAIYU Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was then bent to around 90 degrees using a 2 cm tip. Whole-layer sutures with barbed threads were used to close the myometrium. | 137 min | Improvement in postmenstrual vaginal bleeding, decrease in the depth and width of the cesarean scar defect, and increased residual myometrial thickness. |

| Nyangoh Timoh et al. [22], 2020. Video- case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Robotic-assisted laparoscopy using hysteroscopy treatment. General anesthesia | N.A. | The vesico-uterine cleft was treated as initial stage. To obtain healthy tissue, they ultimately removed the tissue scars from the isthmocele. Additionally, a slow absorption suture of the various regions of the uterus was applied. | 120 min | Successful treatment. |

| Guan et al. [23], 2020. Video-case report | 2 patients, Isthmocele | Robotic single-site laparoscopy and hysteroscopy. General anesthesia | N.A. | The fascia was grabbed and penetrated with Mayo scissors. The bladder was carefully removed from the lower uterine portion and then backfilled. Cold scissors (Endoshears) were used to trim the edges, and in the second surgery, a monopolar hook. Two layers of V-Loc suture were used to close the uterine defect. An extra V-Loc suture was used to seal the peritoneum in a running pattern. | 90 and 85 min (Respectively, for the two patients) | Successful repair of the cesarean scar defect and resolution of the patients’ symptoms. |

| Ye et al. [24], 2020. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. General anesthesia | 7 | Surgery was used to repair the hysterotomy and remove the ectopic pregnancy through a robot-assisted laparoscopic procedure. | N.A. | Effective procedure, no more symptoms. |

| Schmitt et al. [25] 2017. Video-case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and residual CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. General anesthesia | N.A. | Video step-by-step explanation of the procedure trough minimally invasive surgery. | N.A. | Valid correction of the pouch, possibility to treat residual cesarean scar pregnancy. |

| Siedhoff et al. [26], 2015. Video Case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and residual CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. General anesthesia | N.A. | The defect was made visible by opening the vesicovaginal area. Diluted vasopressin was administered. Pregnancy tissue and scar were removed. A delayed-absorbable barbed suture was used to seal the hysterotomy, extending the procedure from laparoscopic myomectomy. The first layer was imbricated with a second. | N.A. | Correction of the defect, no more symptoms, the woman became pregnant. |

| Mahmoud et al. [27], 2015. Video Case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Hysteroscopy and robotic-assisted laparoscopic repair. General anesthesia | / | Executed a bladder flap, the scar tissue around the defect was dissected, and the area closed with delayed absorbable suture. Chromopertubation confirmed the watertightness. | N.A. | Regular normal periods and negative hysterosalpingogram. |

| La Rosa et al. [28], 2013. Review and case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery and hysteroscopy. General anesthesia | / | Adhesiolysis was carried out utilizing electrocautery and sharp dissection. An incision was made in the uterus. Unipolar electrocautery was used to refresh the defect’s edges. Two layers of 0-Vicryl sutures were used to seal the uterus. | N.A. | Successful repair. |

| Yalcinkaya et al. [29], 2011. Cases report | 2 patients, Isthmocele | Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery. General anesthesia | / | Using 45 Watts’ coagulating current and electrode, midline adhesions were taken down between the omentum and abdominal wall, until cervicouterine fascia was clearly detected. Using a hook electrode, the edges were trimmed off. Hemostasis was obtained and the retracted visceral peritoneum was carefully approximated to the pubo-cervico-vesicular fascia at midline to partially cover the peritoneal defect. Vitagel was instilled into the sub-peritoneal region to promote hemostasis. | N.A. | No more symptoms, women became pregnant. |

| Persson et al. [30], 2009. Case report | 1 patient, Isthmocele and CSP | Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery with temporary occlusion of the main uterine blood supply. General anesthesia | 11 | After methotrexate and mifepristone treatments in previous days, the pelvic side walls were surgically dissected and the distal internal iliac arteries were clipped with detachable metal clips (bulldog clips; Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany). The propria ligaments were clamped similarly. Using a laparoscopic retrieval bag and a suction device, the pregnancy was removed. The myometrium surrounding the defect was treated using a single 2-0 Vicryl suture (Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany). The metal clips were finally taken off. | 171 min | Feasible and safe technique for a cesarean scar pregnancy and for the correction of the isthmocele. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Surico, D.; Vigone, A.; Monateri, C.; Tortora, M.; Aquino, C.I. Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Excision and Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Medicina 2025, 61, 1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071123

Surico D, Vigone A, Monateri C, Tortora M, Aquino CI. Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Excision and Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071123

Chicago/Turabian StyleSurico, Daniela, Alessandro Vigone, Carlotta Monateri, Mario Tortora, and Carmen Imma Aquino. 2025. "Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Excision and Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect: A Scoping Review of the Literature" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071123

APA StyleSurico, D., Vigone, A., Monateri, C., Tortora, M., & Aquino, C. I. (2025). Minimally Invasive Surgery for the Excision and Repair of Cesarean Scar Defect: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Medicina, 61(7), 1123. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071123