The Role of Empathy in ADHD Children: Neuropsychological Assessment and Possible Rehabilitation Suggestions—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

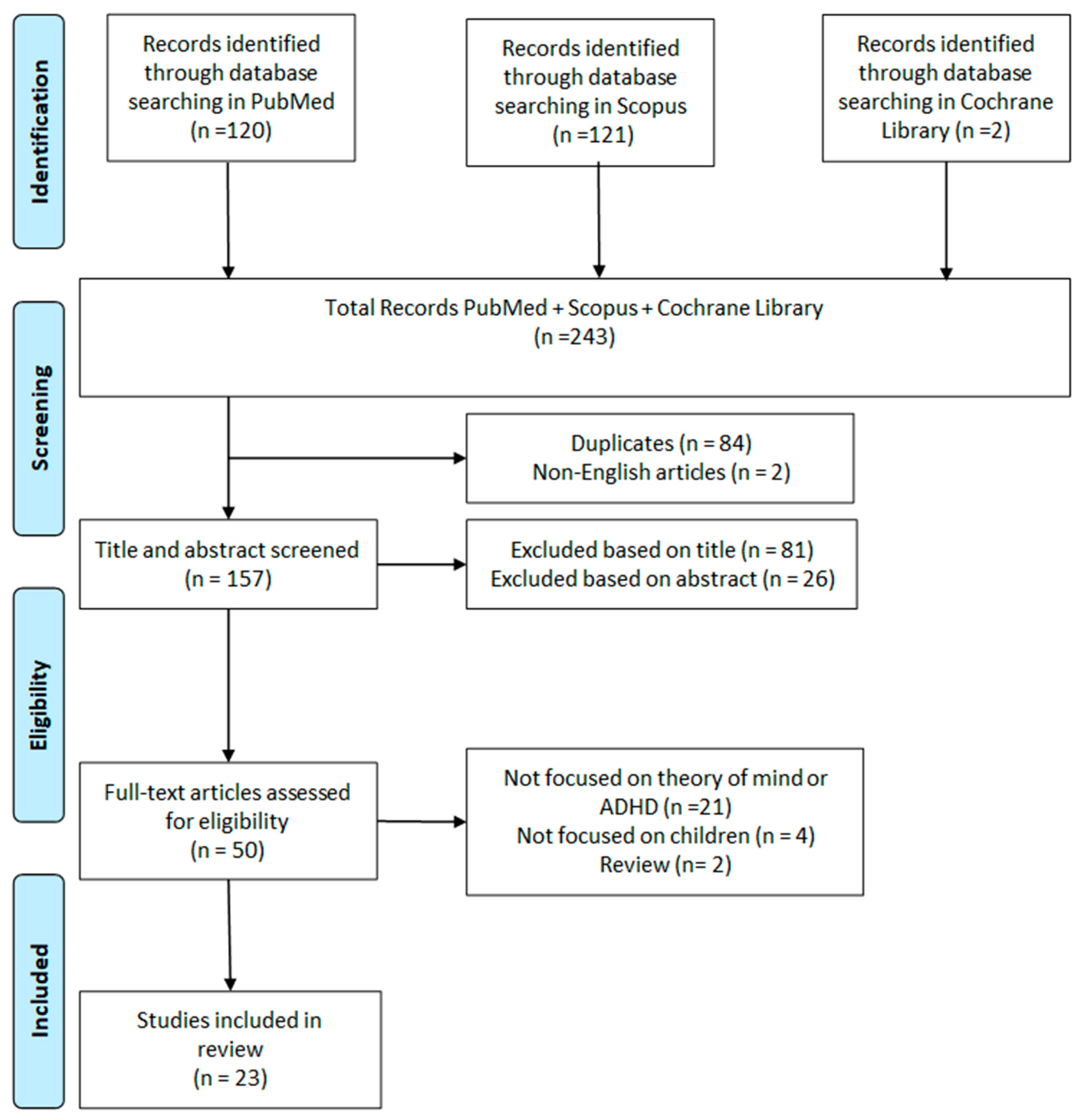

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- The study population included ADHD patients;

- Theory of mind or cognitive empathy was assessed using questionnaires;

- Articles were published in English.

- 4.

- Reviews or meta-analyses;

- 5.

- Conference papers or editorials;

- 6.

- Duplicated studies;

- 7.

- Animal studies.

2.3. Study Selection

3. Results

3.1. False Belief Task (FBT)

3.2. Faux Pas Recognition Test (FPRT)

3.3. Happé’s Strange Stories

3.4. Narrative and Internal State Language (ISL): Telling a Story from a Book

3.5. Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment, Second Edition (NEPSY-II)

3.6. Reading Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET)

3.7. Theory of Mind Assessment Scale (Th.o.m.a.s.)

3.8. Animated Triangles Task—Paradigmatic Task of Moving Forms

3.9. Empathy Quotient (EQ)

3.10. Theory of Mind Inventory, ToM Task Battery

3.11. ToMI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lange, K.W.; Reichl, S.; Lange, K.M.; Tucha, L.; Tucha, O. The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2010, 2, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S.V.; Banaschewski, T.; Coghill, D.; Zheng, Y.; Biederman, J.; Bellgrove, M.A.; Newcorn, J.H.; Gignac, M.; Al Saud, N.M.; Manor, I.; et al. The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 128, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitzianti, M.; Grelloni, C.; Casarelli, L.; D’Agati, E.; Spiridigliozzi, S.; Curatolo, P.; Pasini, A. Neurological soft signs, but not theory of mind and emotion recognition deficit distinguished children with ADHD from healthy control. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, S.; Hechtman, L.; Morgenstern, G. Outcome issues in ADHD: Adolescent and adult long-term outcome n.d. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 1999, 5, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, J.; Joober, R.; Koborsy, B.L.; Mitchell, S.; Sahlas, E.; Palmer, C. Can electroencephalography (EEG) identify ADHD subtypes? A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 139, 104752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demontis, D.; Walters, G.B.; Athanasiadis, G.; Walters, R.; Therrien, K.; Farajzadeh, L.; Voloudakis, G.; Bendl, J.; Zeng, B.; Zhang, W.; et al. Genome-wide analyses of ADHD identify 27 risk loci, refine the genetic architecture and implicate several cognitive domains. MedRxiv 2022, 15, 2022.02.14.22270780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzari, N.; Matvienko-Sikar, K.; Baldoni, F.; O’Keeffe, G.W.; Khashan, A.S. Prenatal maternal stress and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in the offspring: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, B.M.; Class, Q.A.; Rickert, M.E.; Larsson, H.; Långström, N.; Lichtenstein, P. Preterm Birth and Mortality and Morbidity: A Population-Based Quasi-experimental Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 1231–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, H.C.; Holton, K.F.; Anderson, A.N.; Nousen, E.K.; Sullivan, C.A.; Loftis, J.M.; Nigg, J.T.; Sullivan, E.L. Increased Maternal Prenatal Adiposity, Inflammation, and Lower Omega-3 Fatty Acid Levels Influence Child Negative Affect. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 482901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momany, A.M.; Kamradt, J.M.; Nikolas, M.A. A Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Birth Weight and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2018, 46, 1409–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkenstam, E.; Björkenstam, C.; Jablonska, B.; Kosidou, K. Cumulative exposure to childhood adversity, and treated attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A cohort study of 543 650 adolescents and young adults in Sweden. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodlad, J.K.; Marcus, D.K.; Fulton, J.J. Lead and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musser, E.D.; Willoughby, M.T.; Wright, S.; Sullivan, E.L.; Stadler, D.D.; Olson, B.F.; Steiner, R.D.; Nigg, J.T. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and offspring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A quasi-experimental sibling-comparison, population-based design. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2017, 58, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J.T.; Sibley, M.H.; Thapar, A.; Karalunas, S.L. Development of ADHD: Etiology, Heterogeneity, and Early Life Course. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 2, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Yousif, L.H.; Clarke, D.E.; Wang, P.S.; Gogtay, N.; Appelbaum, P.S. DSM-5-TR: Overview of what’s new and what’s changed. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehr, B. American Psychiatric Association explains DSM-5. BMJ 2013, 346, f3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt, E.G. The Prevalence of DSM-IV Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analytic Review. Neurotherapeutics 2012, 9, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabildas, N.; Pennington, B.F.; Willcutt, E.G. A Comparison of the Neuropsychological Profiles of the DSM-IV Subtypes of ADHD. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2001, 29, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Sanders, S.; Doust, J.; Beller, E.; Glasziou, P. Prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e994–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyad, J.; Sampson, N.A.; Hwang, I.; Adamowski, T.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.H.S.G.; Borges, G.; de Girolamo, G.; Florescu, S.; et al. The descriptive epidemiology of DSM-IV Adult ADHD in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2017, 9, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G.; De Lima, M.S.; Horta, B.L.; Biederman, J.; Rohde, L.A. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: A systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowson, J.H. Pharmacological Treatments for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2006, 2, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S. Causal models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: From common simple deficits to multiple developmental pathways. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.A.; Cooper, P.W. Understanding and Supporting Children with ADHD: Strategies for Teachers, Parents and Other Professionals; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg, J.T. What Causes ADHD?: Understanding What Goes Wrong and Why; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.E. A New Understanding of ADHD in Children and Adults: Executive Function Impairments; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A.; Murphy, K.R. The Nature of Executive Function (EF) Deficits in Daily Life Activities in Adults with ADHD and Their Relationship to Performance on EF Tests. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011, 33, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Alhucema, W.; Aristizabal, E.; Escudero-Cabarcas, J.; Acosta-López, J.E.; Vélez, J.I. Executive Function and Theory of Mind in Children with ADHD: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2018, 28, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milich, R.; Balentine, A.C.; Lynam, D.R. ADHD combined type and ADHD predominantly inattentive type are distinct and unrelated disorders. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2001, 8, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheres, A.; Oosterlaan, J.; Geurts, H.; Morein-Zamir, S.; Meiran, N.; Schut, H.; Vlasveld, L.; Sergeant, J.A. Executive functioning in boys with ADHD: Primarily an inhibition deficit? Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2004, 19, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, H.M.; Verté, S.; Oosterlaan, J.; Roeyers, H.; Sergeant, J.A. ADHD subtypes: Do they differ in their executive functioning profile? Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2005, 20, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, A.; Slama, H.; Mousty, P.; Massat, I.; Capiau, T.; Drabs, V.; Peigneux, P. Executive and attentional contributions to Theory of Mind deficit in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Child. Neuropsychol. 2016, 22, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Campbell, R.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Grant, J.; Walker, J. Are children with autism blind to the mentalistic significance of the eyes? Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 13, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Arun, P.; Bajaj, M.K. Theory of Mind and Executive Functions in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Specific Learning Disorder. Indian. J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanipour, S.; Sheikh, M.; Shayestefar, M.; Baloochnejad, T. Deficits in Working Memory and Theory of Mind May Underlie Difficulties in Social Perception of Children with ADHD. Neurol. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 3793750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decety, J.; Jackson, P.L. The Functional Architecture of Human Empathy. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 2004, 3, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decety, J.; Lamm, C. The Biological Basis of Empathy. In Handbook of Neuroscience for the Behavioral Sciences; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Target, M. The Mentalization-Focused Approach to Self Pathology. J. Pers. Disord. 2006, 20, 544–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüne, M. “Theory of Mind” in Schizophrenia: A Review of the Literature. Schizophr. Bull. 2005, 31, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löytömäki, J.; Ohtonen, P.; Laakso, M.L.; Huttunen, K. The role of linguistic and cognitive factors in emotion recognition difficulties in children with ASD, ADHD or DLD. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2020, 55, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevincok, D.; Avcil, S.; Ozbek, M.M. The relationship between theory of mind and sluggish cognitive tempo in school-age children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoz, H.; Gvirts, H.Z.; Sheffer, M.; Bloch, Y. Theory of Mind and Empathy in Children with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2017, 23, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbaran, B.; Kalyoncu, T.; Köse, S. Theory of mind and emotion regulation difficulties in children with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilincel, S. The Relationship between the Theory of Mind Skills and Disorder Severity among Adolescents with ADHD. Alpha Psychiatry 2021, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dağdelen, F. Decreased Theory of Mind Abilities and Increased Emotional Dysregulation in Adolescents with ASD and ADHD. Alpha Psychiatry 2021, 22, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillies, S.; Bertot, V.; Motte, J.; Raynaud, C.; Abely, M. Social cognition in ADHD: Irony understanding and recursive theory of mind. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 3191–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razjouan, K.; Hosseinzadeh, M.; Zahed, G.; Khademi, M.; Davari, R.; Arabgol, F. Theory of mind in adolescents with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A cross-sectional study. Iran. J. Child. Neurol. 2023, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parke, E.M.; Becker, M.L.; Graves, S.J.; Baily, A.R.; Paul, M.G.; Freeman, A.J.; Allen, D.N. Social Cognition in Children with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Yıldırım Demirdöğen, E.; Kolak Çelik, M.; Akıncı, M.A. An assessment of dynamic facial emotion recognition and theory of mind in children with ADHD: An eye-tracking study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Son, J.W.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.E.; Chung, S.; Ghim, H.R.; Lee, S.-I.; Shin, C.-J.; Ju, G. Disrupted Association Between Empathy and Brain Structure in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Korean Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 32, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, A.L.; Kamp-Becker, I.; Becker, K.; Kauschke, C. Narrative competence and internal state language of children with Asperger Syndrome and ADHD. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.; Tehrani-Doost, M.; Khorrami, A.; Noorian, N. Understanding intentionality in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2016, 8, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz Kafali, H.; Kayan Ocakoğlu, B.; Işık, A.; Ayvalık Baydur, Ü.G.; Müjdecioğlu Demir, G.; Şahin Erener, M.; Üneri, Ö.Ş. Theory of mind failure and emotion dysregulation as contributors to peer bullying among adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children’s Health Care 2021, 50, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demurie, E.; De Corel, M.; Roeyers, H. Empathic accuracy in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, A.; Khorrami Banaraki, A.; Tehrani Doost, M.; Castelli, F. A new semi-nonverbal task glance, moderate role of cognitive flexibility in ADHD children’s theory of mind. Cogn. Neuropsychiatry 2020, 25, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolat, N.; Eyüboğlu, D.; Eyüboğlu, M.; Eliacik, K. Emotion recognition and theory of mind deficits in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Anatol. J. Psychiatry 2017, 18, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, S.; Yao, S.; Su, L.; McWhinnie, C. The relationship between theory of mind and executive function in a sample of children from mainland China. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2009, 40, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perner, J.; Kain, W.; Barchfeld, P. Executive control and higher-order theory of mind in children at risk of ADHD. Infant. Child. Dev. 2002, 11, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, C.; Roselló, B.; Colomer, C.; Baixauli, I.; Miranda, A. Children with autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Relationships between symptoms and executive function, theory of mind, and behavioral problems. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 83, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, H.; Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 1983, 13, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; O’Riordan, M.; Stone, V.; Jones, R.; Plaisted, K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1999, 29, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happé, F.G.E. An advanced test of theory of mind: Understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 1994, 24, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeghly, M.; Bretherton, I.; Mervis, C.B. Mothers’ internal state language to toddlers. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 4, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkman, M.; Kirk, U.; Kemp, S. NEPSY II: Administrative Manual; Harcourt Assessment, PsychCorp: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test Revised Version: A Study with Normal Adults, and Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High-functioning Autism. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, F.M.; Colle, L.; Pecorara, R.S.; Tirassa, M. ThOMAS, Theory of Mind Assessment Scale: Uno strumento per la valutazione della teoria della mente. Sistemi Intelligenti 2006, XVIII, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abell, F.; Happé, F.; Frith, U. Do triangles play tricks? Attribution of mental states to animated shapes in normal and abnormal development. Cogn. Dev. 2000, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, T.L.; Prelock, P.A.; Bonazinga, L. Psychometric evaluation of the Theory of Mind Inventory (ToMI): A study of typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2012, 42, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, R.; Brem, S.; Brandeis, D.; Grünblatt, E.; Berger, G.; Walitza, S. ADHD: Current concepts and treatments in children and adolescents. Neuropediatrics 2020, 51, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.D.I.; Liu, S.; Soares, N. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, risk factors and evaluation in youth. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosello, B.; Berenguer, C.; Baixauli, I.; García, R.; Miranda, A. Theory of Mind Profiles in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Adaptive/Social Skills and Pragmatic Competence. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 567401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferberg, A.; Hasler, G. The social cost of depression: Investigating the impact of impaired social emotion regulation, social cognition, and interpersonal behavior on social functioning. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S.; Becker, S.P.; Bölte, S.; Castellanos, F.X.; Franke, B.; Newcorn, J.H.; Nigg, J.T.; Rohde, L.A.; Simonoff, E. Annual Research Review: Perspectives on progress in ADHD science—from characterization to cause. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2023, 64, 506–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storebø, O.J.; Andersen, M.E.; Skoog, M.; Hansen, S.J.; Simonsen, E.; Pedersen, N.; Tendal, B.; Callesen, H.E.; Faltinsen, E.; Gluud, C. Social skills training for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD008223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, B.; Mota, B.; Viana, V.; Igreja, A.I.; Candeias, L.; Rocha, H.; Guardiano, M. Theory of mind in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Rev. Neurol. 2023, 77, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, B.; Karabekiroğlu, K.; Bozkurt, A.; Usta, M.B.; Aydın, M.; Çobanoğlu, C. The Relationship of Clinical Symptoms with Social Cognition in Children Diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Specific Learning Disorder or Autism Spectrum Disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, J.; Golec, K.; Haman, M.; Wolak, T.; Kochański, B.; Pluta, A. Processing False Beliefs in Preschool Children and Adults: Developing a Set of Custom Tasks to Test the Theory of Mind in Neuroimaging and Behavioral Research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 493479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, C.C.; Alderson, R.M.; Roberts, D.K.; Tatsuki, M.O.; Sullivan, M.A.; Kofler, M.J. Social functioning in children with ADHD: An examination of inhibition, self-control, and working memory as potential mediators. Child Neuropsychol. 2024, 30, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovagnoli, A.R.; Bell, B.; Erbetta, A.; Paterlini, C.; Bugiani, O. Analyzing theory of mind impairment in patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K. Unraveling Generational Threads: Navigating the Familial Landscape of ADHD from a Developmental Lens. Ph.D. Thesis, Guilford College, Greensboro, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaland, N.; Møller-Nielsen, A.; Smith, L.; Mortensen, E.L.; Callesen, K.; Gottlieb, D. The Strange Stories test: A replication study of children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 14, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikou, E.G.; Thompson, W.J. Assessing Cognitive and Affective Empathy Through the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Assessment 2015, 23, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, M.J.; Groves, N.B.; Chan, E.S.M.; Marsh, C.L.; Cole, A.M.; Gaye, F.; Cibrian, E.; Tatsuki, M.O.; Singh, L.J. Working memory and inhibitory control deficits in children with ADHD: An experimental evaluation of competing model predictions. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1277583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik-Parvinchi, D.; Wright, L.; Schachar, R. Cognitive Rehabilitation for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Promises and Problems. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, L.Y.C.; Taechameekietichai, Y.; Allen, J.L. Individual child factors affecting the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Criterion | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inattention | A. Attention to details | Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, or other activities. |

| B. Sustained attention | Has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities (e.g., during lessons, conversations, or extended reading). | |

| C. Listening | Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly (appears to be elsewhere mentally). | |

| D. Following instructions | Fails to follow through on instructions and does not complete schoolwork, chores, or workplace duties. | |

| E. Organization | Has difficulty organizing tasks and activities (e.g., managing time, keeping materials in order, meeting deadlines). | |

| F. Avoidance of sustained effort | Avoids or is reluctant to engage in tasks requiring sustained mental effort. | |

| G. Losing necessary items | Frequently loses objects necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., school supplies, keys, documents). | |

| H. Easily distracted | Is easily distracted by extraneous stimuli or unrelated thoughts. | |

| I. Forgetfulness | Often forgets daily activities (e.g., chores, appointments, bill payments). | |

| Hyperactivity/Impulsivity | A. Motor restlessness | Often fidgets with hands or feet, squirms in seat. |

| B. Leaving seat frequently | Gets up in situations where remaining seated is expected. | |

| C. Excessive movement | Runs or climbs in inappropriate situations (in adults, this may manifest as restlessness). | |

| D. Difficulty playing quietly | Struggles to engage in leisure activities quietly. | |

| E. Always “on the go” | Acts as if “driven by a motor,” has difficulty staying still. | |

| F. Excessive talking | Talks excessively, struggles to regulate speech. | |

| G. Impulsively answering | Answers before a question is completed, interrupts others. | |

| H. Difficulty waiting turn | Struggles to wait for their turn in social situations or games. | |

| I. Interrupting and intruding | Interrupts conversations or intrudes on others’ activities. | |

| General diagnostic requirements | Persistence of symptoms | Several symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity persisted for at least 6 months at a level inconsistent with developmental stage and negatively impacting social, academic, or occupational activities. |

| Early onset of symptoms | Several symptoms of inattention or hyperactivity-impulsivity were present before the age of 12. | |

| Symptoms in multiple settings | Symptoms are present in two or more settings (e.g., at home, school, or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities). | |

| Significant impairment | Clear evidence that symptoms interfere with social, academic, or occupational functioning or reduce quality of life. | |

| Exclusion of other disorders | Symptoms do not occur exclusively during schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder and are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, personality disorder, substance intoxication, or withdrawal). |

| Study | Population | Control Group | First Order Empathy Measure | Second Order Empathy Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Löytömäki 2020 [42] | 20 ASD (2 female) mean age 8.25 (SD = 1.21); 17 ADHD (3 female) mean age 8.06 (1.30); 13 DLD (4 female) mean age 7.62 (1.61) | TD: 106 (59 female). Mean age 8.02 SD = 1.42) | Sally–Anne task | Ice Cream Truck/Van Task | Children with ADHD exhibited notably lower ToM performance than TD group |

| Sevincok 2021 [43] | 50 ADHD (7 female) age 10.00 (SD = 1.70) | 40 TD (6 female) age 11.80 (SD = 2.00) | Sally–Anne task; RMET | NA | All ToM scores were significantly lower in children with ADHD than in TD children |

| Maoz 2017 [44] | 24 ADHD (66% male) age 10.28 (SD = 1.64) | 36 TD (53% male) 9.37 (SD = 1.35) | FPRT | IRI | Children with ADHD displayed reduced self-reported empathy |

| Özbaran 2018 [45] | 100 ADHD (41 female) 14.03 (SD = 1.75) | 100 TD (41 female) 14.03 (SD = 1.75) | RMET | UOT | ToM scores were lower in children with ADHD, and a significant link between ToM abilities (especially UOT) and emotion regulation was observed |

| Kılınçel 2021 [46] | 42 ADHD (52.4% male) 13.20 (SD = 1.30) | 41 TD (56.1% male) 12.10 (SD = 2.51) | FPRT, Smarties Test | II Order: Ice Cream Truck Test | ToM skills were impaired in adolescents with ADHD and were linked to the severity of the disorder |

| Dağdelen 2021 [47] | 60 ADHD (30 female) 14 (SD = 1.43); 60 SD (30 female) 14.02 (SD = 14,44) | 60 TD (30 female) age 13.55 (SD = 1.41) | FPRT, RMET, the Hinting Task | DERS | Adolescents with ASD and ADHD had weaker ToM and ER abilities than TD, and ToM impairments negatively affected ER in all groups |

| Singh 2021 [35] | 20 ADHD 10.00 (SD = 2.29) (3 female); 20 SLD 11.45 (SD = 2.18) | 20 TD 11.35 (SD = 2.51) 11.45 (SD = 2.18) | ToMI, ToM task battery | NA | Children with ADHD showed greater deficits in ToM tasks than children with SLD and TD of similar age and education |

| Cailles 2014 [48] | 15 ADHD (5 female), mean age 9 (SD = 1.3) | 15 TD mean age 9 (SD = 1.93) | NA | The ice cream story, the birthday story | Only 5 out of 15 children with ADHD succeeded in the second-order false-belief tasks, compared with 14 out of 15 controls |

| Razjouan 2023 [49] | 52 ADHD (31 female) 14.05 (SD = 1.81) | 42 TD (12 female) 14.32 (SD = 2.49) | Th.o.m.a.s.; RMET | NA | No significant differences in ToM abilities were found between the two groups, nor was any correlation found between ToM scores and sociocultural factors |

| Parke 2018 [50] | 25 ADHD (70% male) 10.57 (SD = 2.09) | 25 TD (60% male) 10.07 (SD = 1.90) | Happé’s Strange Stories; IRI; NEPSY II; RMET | NA | Children with ADHD performed worse on cognitive ToM, affect recognition, and cognitive empathy than TD peers |

| Bozkurt 2024 [51] | 47 ADHD 10.0 years (SD = 1.7) (9 female) | 38 TD 10.6 (SD = 1.8) (10 female) | RMET; FPRT | NA | The recognition of disgust and ToM skills were positively correlated, suggesting distinct deficits in social cognition related to emotion recognition |

| Lee 2014 [52] | 14 ADHD (14 male) 13.37 years (SD = 0.90) | 19 TD (11 male) 13.35 (SD = 1.18) | IRI; EQ-C-CEE; EQ-C-CE | NA | The ADHD group had a smaller cortical volume linked to emotional empathy than the control group, with no brain region showing a significant correlation with empathy |

| Rumpf 2012 [53] | 11 ADHD (1 female); 9.11 years, (SD = 11.8) 11 AS (all males) 10.5 years, (SD = 16.9) | 11 TD (1 female) 9.11 years, (SD = 11.8) | Telling a story from a book | NA | Children with ADHD had ISL use similar to HC, suggesting no significant impairment in emotional empathy |

| Mary 2015 [33] | 30 ADHD 10.3 years (SD = 1.28) | 31 TD 10.0 years (SD = 1.0) | RMET; FPRT | NA | ToM deficits in children with ADHD were primarily due to impairments in attention and EFs, which may contribute to their socioemotional difficulties |

| Mohammadzadeh 2016 [54] | 30 ADHD 7.70 years, (SD = 1.77) | 30 TD 9 years (SD = 1.94) | Moving shapes paradigm task (or animated triangles) | NA | Children with ADHD performed significantly worse than normal children (p < 0.05) in comprehending others’ intentionality |

| Yilmaz Kafali 2021 [55] | 15 ADHD, 13.9 ± 1.8 years (77 male). | RMET | NA | Adolescents with ADHD who were victims or perpetrators of bullying demonstrated poorer ToM abilities than those who were not involved in bullying | |

| Demurie 2011 [56] | 13 ADHD (1 female) 13.69 (SD = 1.43) 13 ASD (1 female) 14.35 (SD = 1.24) | 18 TD (4 female) 13.86 (SD = 1.73) | IRI, RMET | EAT | Adolescents with ADHD showed similar empathic accuracy to those with ASD and controls, suggesting mind-reading deficits potentially linked to inhibitory control issues |

| Mohammadzadeh 2019 [57] | ADHD 30 7.28 (SD = 1.64) | 30 TD 7 years, (SD = 1.34) | Animated Triangles Task | NA | ADHD group had a significant ToM and EF impairment relative to the TD group |

| Bolat 2017 [58] | ADHD 69 (21 females), 10.17 years (SD = 1.99). | 69 TD (21 females), 10.28 years (SD = 2.10). | First- and second-order false belief Tasks; CT | UOT | ADHD had an independent negative effect on overall ToM and emotion recognition abilities |

| Yang 2009 [59] | ADHD 26 participants (4 females), 8.2 years (SD = 2.9). ASD 20 (2 females) 8.1 years (SD = 3.5) | 30 TD participants (3 females) 8.0 years (SD = 3.1). | Appearance–Reality Task, Unexpected-Location Task | Unexpected-Content Task | Children with ADHD performed similarly to TD children on ToM tasks, showing no significant deficits in first-order or second-order ToM |

| Perner 2002 [60] | ADHD 24 children, 67.0 months (SD = 7.1). | 22 TD 69.4 months (SD = 7.1). | NA | Second-order false belief task | The at-risk ADHD group performed worse than the control group on several executive tasks but showed no impairment on the advanced Tom tasks |

| Pitzianti 2017 [3] | ADHD group: 23 (9 females), 10.39 years (SD = 2.35) | 20 TD (9 females) 9.10 years (SD = 1.92). | NEPSY-II | NA | The study found no significant differences in ToM or emotion recognition performance between children with ADHD and TD, suggesting that ToM and ER deficits were not a consistent feature in ADHD |

| Berenguer 2018 [61] | ADHD 26, 9.96 years (SD = 14.93) ASD 19, 9.68 years (SD = 24.63) | 30 TD 9.23 years (SD = 12.06) | ToMI; NEPSY-II | NA | Children with ADHD showed impairments in ToM tasks, performing better than those with ASD but worse than those TD, especially in applying ToM knowledge to real-life situations |

| Test | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| False Belief Task (FBT) | Widely used and well-established; detects impairments at both first- and second-order levels; sensitive to difficulties in understanding others’ beliefs and intentions [62]. | Some studies have shown inconsistent results in second-order tasks; the relationship with executive functions (EF) may vary [62]. |

| False Passage Recognition Test (FPRT) | Effectively evaluates social cognition and ToM deficits [63]; can highlight correlations with symptom severity (e.g., inattention, impulsivity) [63]. | Variability related to age and sample size [63]. |

| Happé’s Strange Stories | Highlights difficulties in interpreting complex social interactions and subtle intentions [64]. | Focus on complex scenarios that might limit generalizability [50]. |

| Narrative and Internal State Language (ISL) | Helps distinguish deficits in narrative coherence [65]. | Grammatical skills may remain intact, masking difficulties [53]. |

| NEPSY-II | Allows investigation of the relationship between executive functions and ToM [66]. | Variable results in subtests due to discrepancies in emotion recognition and the relationship with executive functions [66]. |

| Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET) | Complementary data (e.g., eye-tracking) highlight differences between ADHD and TD groups [67]. | Possible confusion between visual attention and ADHD symptoms; variations based on the age of the sample [67]. |

| Theory of Mind Assessment Scale (Thomas) | Effective for assessing ToM and EF and for group comparisons [68]. | Has not always shown significant differences between children with ADHD and TD [68]. |

| Animated Triangles Task | Detects deficits in attributing mental states to abstract stimuli [69]. | Correlation with executive functions is not always clear [69]. |

| Empathy Quotient (EQ) | Investigates the cognitive dimensions of empathy and highlights deficits in perspective-taking [41]. | Risk of self-report bias [41]. |

| Theory of Mind Inventory, TOM Battery | Comprehensive approach covering early, basic, and advanced levels of ToM; useful for differentiating ADHD, DSA, and TD [35]. | Complex administration; possible caregiver report bias [35]. |

| ToMI (Theory of Mind Inventory) | Revised version that assesses ToM through parent reports; highlights differences between groups (ADHD, ASD, TD) and covers various ToM abilities [70]. | Difficulty in clearly separating ToM deficits from those of EF [70]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Casula, A.; Belluardo, G.; Antenucci, C.; Bianca, F.; Corallo, F.; Ferraioli, F.; Gargano, D.; Giuffrè, S.; Giunta, A.L.C.; La Torre, A.; et al. The Role of Empathy in ADHD Children: Neuropsychological Assessment and Possible Rehabilitation Suggestions—A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030505

Casula A, Belluardo G, Antenucci C, Bianca F, Corallo F, Ferraioli F, Gargano D, Giuffrè S, Giunta ALC, La Torre A, et al. The Role of Empathy in ADHD Children: Neuropsychological Assessment and Possible Rehabilitation Suggestions—A Narrative Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(3):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030505

Chicago/Turabian StyleCasula, Antony, Giulia Belluardo, Carmine Antenucci, Federica Bianca, Francesco Corallo, Francesca Ferraioli, Domenica Gargano, Salvatore Giuffrè, Alice Lia Carmen Giunta, Antonella La Torre, and et al. 2025. "The Role of Empathy in ADHD Children: Neuropsychological Assessment and Possible Rehabilitation Suggestions—A Narrative Review" Medicina 61, no. 3: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030505

APA StyleCasula, A., Belluardo, G., Antenucci, C., Bianca, F., Corallo, F., Ferraioli, F., Gargano, D., Giuffrè, S., Giunta, A. L. C., La Torre, A., Massimino, S., Mirabile, A., Parisi, G., Pizzuto, C. D., Spartà, M. C., Tartaglia, A., Tomaiuolo, F., & Culicetto, L. (2025). The Role of Empathy in ADHD Children: Neuropsychological Assessment and Possible Rehabilitation Suggestions—A Narrative Review. Medicina, 61(3), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030505