Cutaneous Anguillulosis During Immunotherapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

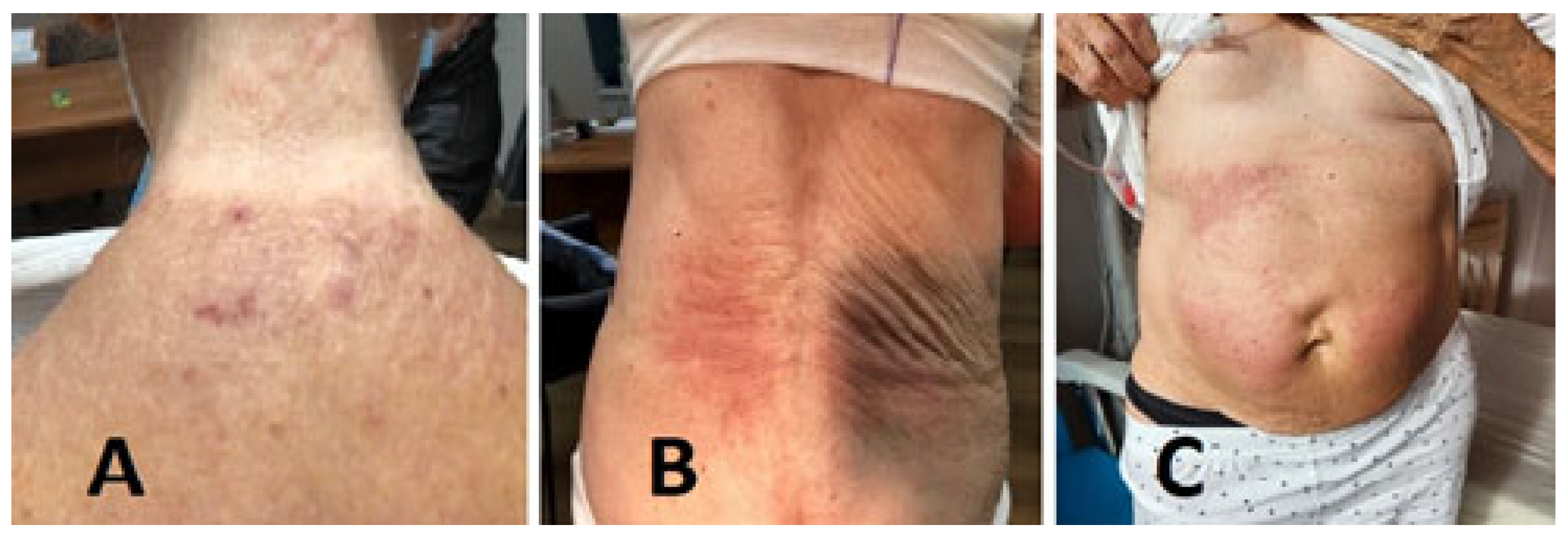

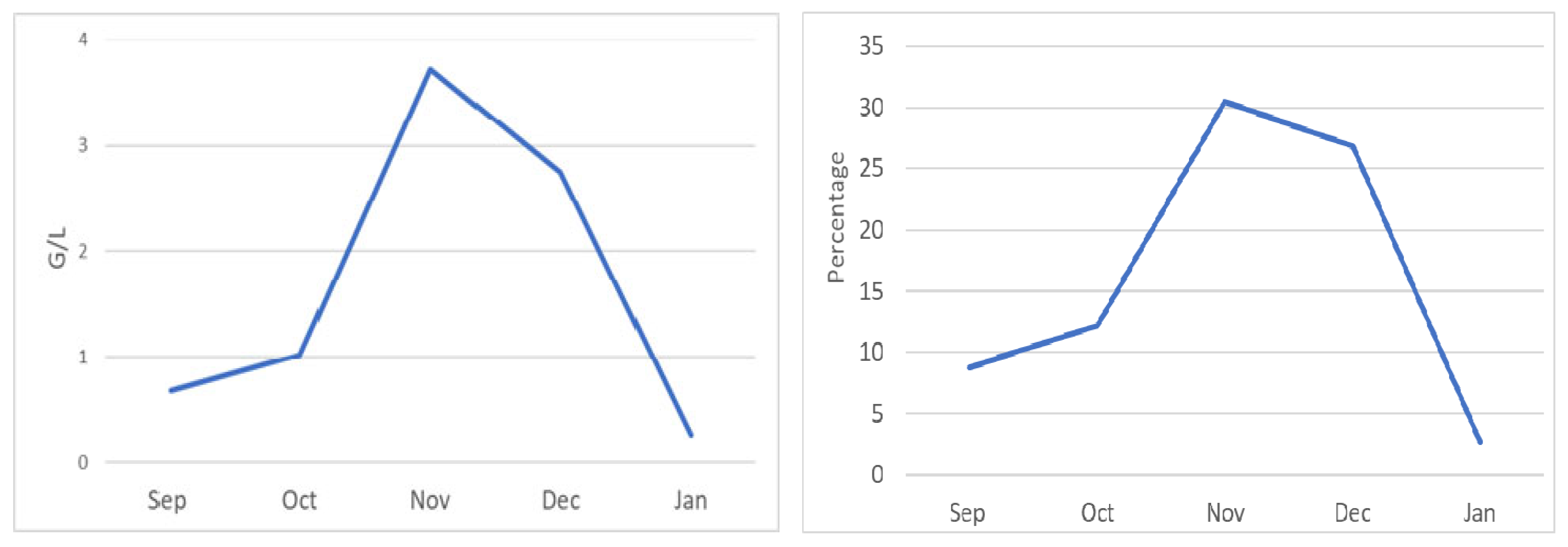

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forman, R.; Long, J.B.; Westvold, S.J.; Agnish, K.; McManus, H.D.; Leapman, M.S.; Hurwitz, M.E.; Spees, L.P.; Wheeler, S.B.; Gross, C.P.; et al. Cost trends of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Therapy: The impact of oral anticancer agents and immunotherapy. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, X.; Chevalier, B.; Klotz, F. Anguillule et anguillulose. EMC-Mal. Infect. 2005, 2, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourée, P.; Taugourdeau, A.; Barthélémy, M.; PequignotRicome, H.; Passeron, J.; Bouvier, J.B. Anguillulose: Analyse clinique, biologique et épidémiologique de 350 observations. Nouv. Presse Medicale 1981, 10, 679–681. [Google Scholar]

- Gann, P.H.; Neva, F.A.; Gam, A.A. A randomized trial of single- and two-dose ivermectin versus thiabendazole for treatment of strongyloidiasis. J. Infect. Dis. 1994, 169, 1076–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loutfy, M.R.; Wilson, M.; Keystone, J.S.; Kain, K.C. Serology and eosinophil count in the diagnosis and management of strongyloidiasis in a non-endemic area. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002, 66, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corona-Rodarte, E.; Olivas-Martínez, A.; Remolina-Bonilla, Y.A.; Domínguez-Cherit, J.G.; Lam, E.T.; Bourlon, M.T. Do we need skin toxicity? Association of immune checkpoint inhibitor and tyrosine kinase inhibitor-related cutaneous adverse events with outcomes in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamińska-Winciorek, G.; Cybulska-Stopa, B.; Lugowska, I.; Ziobro, M.; Rutkowski, P. Principles of prophylactic and therapeutic management of skin toxicity during treatment with checkpoint inhibitors. Postępy Dermatol. I Alergol. 2019, 36, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guinat, M.; Rusca, M.; Stalder, M.; Praz, G. Eosinophilie: De la néoplasie à l’anguillulose [Eosinophilia: From neoplastic disease to anguillulosis]. Rev. Medicale Suisse 2014, 10, 1853-4–1856-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jouini, R.; Hedhli, R.; Khanchel, F.; Sabbah, M.; Trad, D.; Hlel, I.; Koubaa, W.; Khayat, O.; Ben Brahim, E.; Debbiche, A.C. Anguillulosis: Circumstances of infestation and evolution towards the malignant form. Tunis. Medicale 2019, 97, 1419–1421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.D.; Wilkinson, R.J. Immune reconstitution disease associated with parasitic infections following antiretroviral treatment. Parasite Immunol. 2006, 28, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Breton, G. Syndrome inflammatoire de reconstitution immune [Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome or IRIS]. Med. Sci. 2010, 26, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottlaender, L.; Sève, P.; Cotte, L.; Gerfaud-Valentin, M.; Jamilloux, Y. Successful treatment with anakinra of an HIV-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome mimicking adult-onset Still’s disease. Rheumatology 2019, 58, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muço, E.; Karruli, A.; Hoxha, N.; Hoxhaj, A.; Kokici, M. Visceral Leishmaniasis and Herpes Zoster as a Component of Syndrome of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in an HIV-Positive Patient. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2022, 2022, 2784898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lawn, S.D. Immune reconstitution disease associated with parasitic infections following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 20, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, S.; Fernández, G.; Kapila, R.; Lambert, W.C.; Schwartz, R.A. Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis associated with the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Examination Name | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Blood—Virology | HIV1, HIV2, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C | Negative |

| Blood—Antibody | Anti-Skin, Anti-HuD, Anti-Yo, Anti-Ri, Anti-CV2, Anti-Amphiphysin, Anti-Ma1, Anti-Ma2, Anti-GAD65, Anti-Sox1, Anti-Tr, Anti-Zic4, Anti-Titin (MGT30), Anti-PKCgamma, Anti-Recoverin | Negative |

| Blood—Parasitology Stool—Parasitology | Anguillulosis, Bilharziasis, Distomatosis, Filariosis, Toxocarosis, Trichinosis Check for eggs, cysts, or larvae of adult parasites | Anguillulosis + Negative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cornillon, P.; Beguinot, M.; Maillet, D.; Bouleftour, W.; Bouqallaba, Y.; Flori, P.; Corbaux, P.; Li, G. Cutaneous Anguillulosis During Immunotherapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Medicina 2025, 61, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020339

Cornillon P, Beguinot M, Maillet D, Bouleftour W, Bouqallaba Y, Flori P, Corbaux P, Li G. Cutaneous Anguillulosis During Immunotherapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Medicina. 2025; 61(2):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020339

Chicago/Turabian StyleCornillon, Pierre, Marie Beguinot, Denis Maillet, Wafa Bouleftour, Yanis Bouqallaba, Pierre Flori, Pauline Corbaux, and Guorong Li. 2025. "Cutaneous Anguillulosis During Immunotherapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma" Medicina 61, no. 2: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020339

APA StyleCornillon, P., Beguinot, M., Maillet, D., Bouleftour, W., Bouqallaba, Y., Flori, P., Corbaux, P., & Li, G. (2025). Cutaneous Anguillulosis During Immunotherapy for Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Medicina, 61(2), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020339