Estrogen Treatment Lowers the Risk of Complications in Menopausal Women with Mild Burn Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

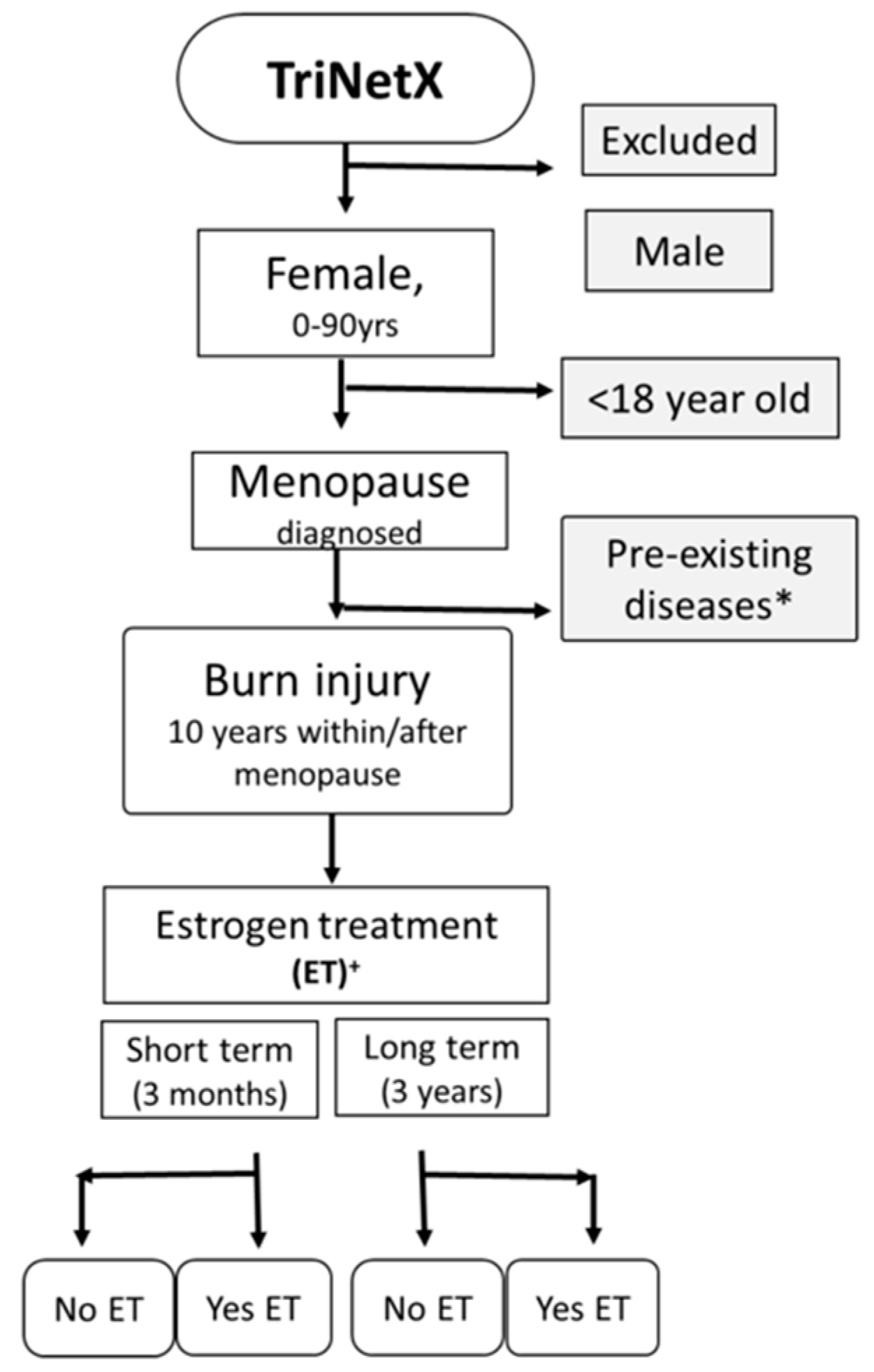

2. Methods

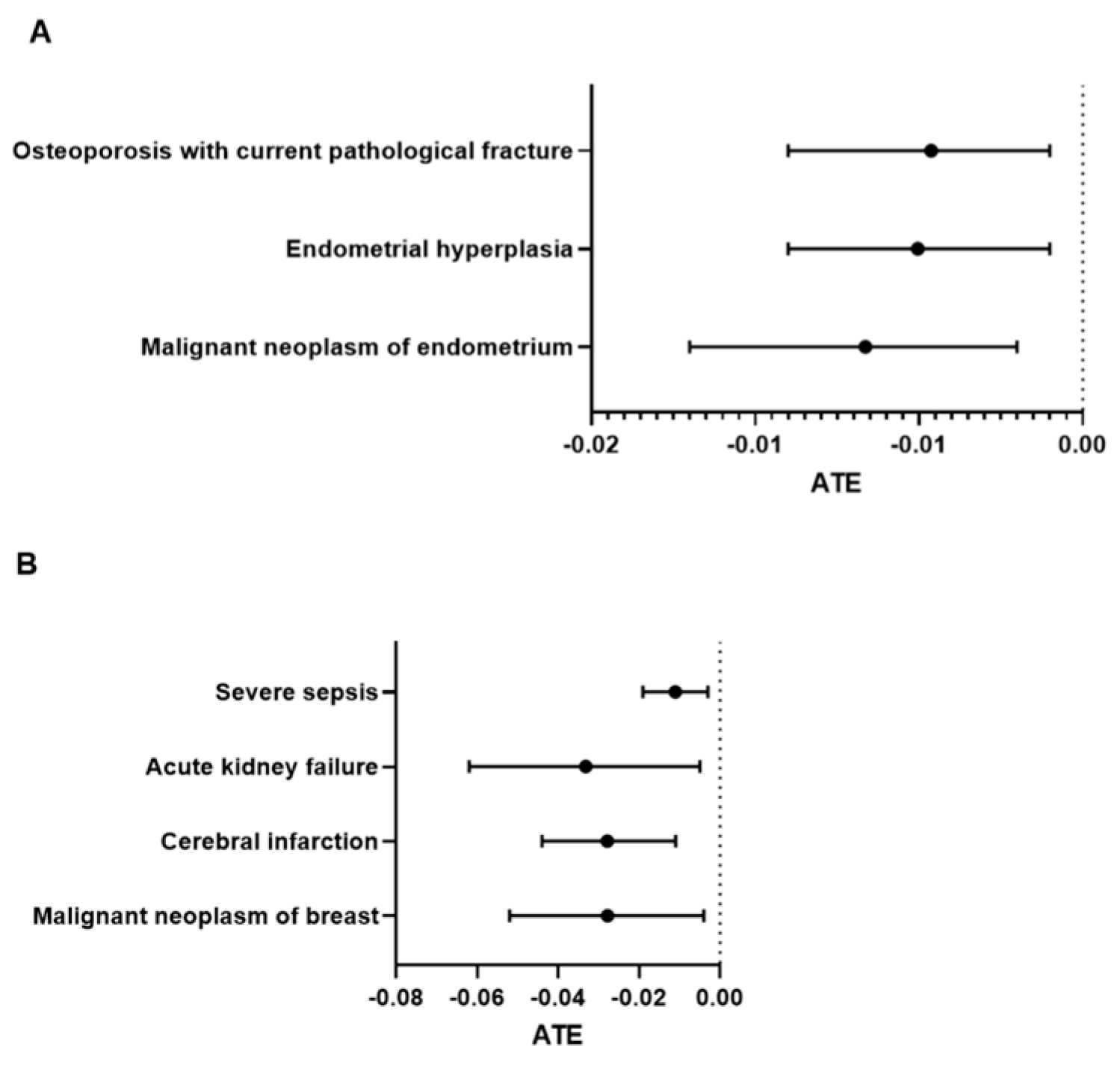

3. Results

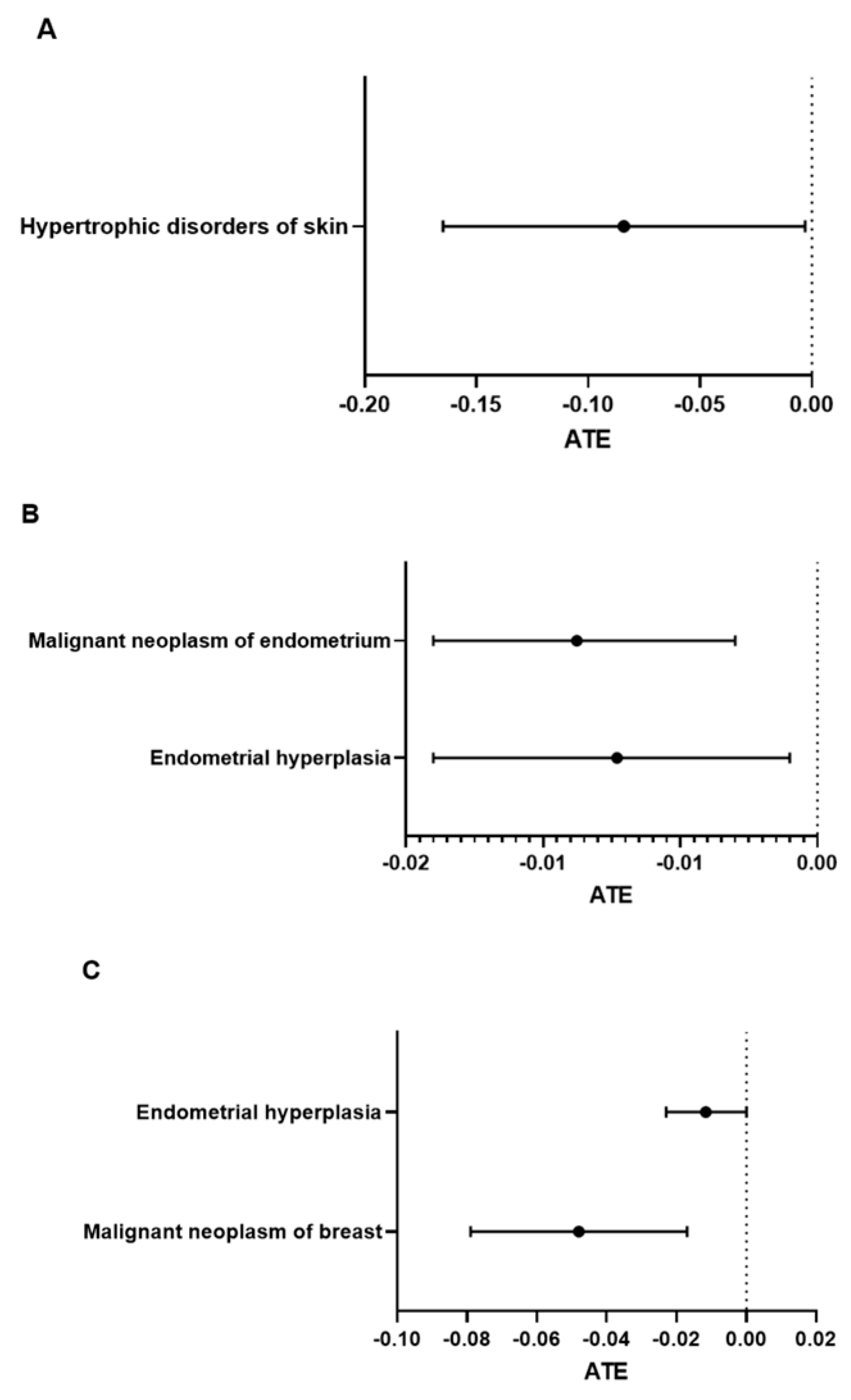

Long-Term (3-Year) Complications in Postmenopausal Burn Patients with Estrogen Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, L. Women live longer than men but have more illness throughout life, global study finds. BMJ 2024, 385, q999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, M.D. Epidemiology of burns throughout the world. Part I: Distribution and risk factors. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2011, 37, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Burn Association NBR Advisory Committee. National Burn Repository; American Burn Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.W.; Fear, V.S.; Waithman, J.C.; Wood, F.M.; Fear, M.W. Understanding acute burn injury as a chronic disease. Burn. Trauma 2019, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Beld, A.W.; Kaufman, J.M.; Zillikens, M.C.; Lamberts, S.W.J.; Egan, J.M.; van der Lely, A.J. The physiology of endocrine systems with ageing. Lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.R.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Lumsden, M.; Mishra, G.D.; Pal, L.; Rees, M.; Santoro, N.; Simoncini, T. Menopause. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.; Ho, V.; Pasquet, R.; Singh, R.J.; Goetz, M.P.; Tu, D.; Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N. Baseline estrogen levels in postmenopausal women participating in the MAP.3 breast cancer chemoprevention trial. Menopause 2020, 27, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteley, J.; DiBonaventura, M.; Wagner, J.S.; Alvir, J.; Shah, S. The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes. J. Women’s Health 2013, 22, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tarrah, K.; Moiemen, N.; Lord, J.M. The influence of sex steroid hormones on the response to trauma and burn injury. Burn. Trauma 2017, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, C.R.; Plackett, T.P.; Kovacs, E.J. Aging and estrogen: Modulation of inflammatory responses after injury. Exp. Gerontol. 2007, 42, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.P.; Chaudry, I.H. The role of estrogen and receptor agonists in maintaining organ function after trauma-hemorrhage. Shock 2009, 31, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wigginton, J.G.; Maass, D.L.; Ma, L.; Carlson, D.; Wolf, S.E.; Minei, J.P.; Zang, Q.S. Estrogen-provided cardiac protection following burn trauma is mediated through a reduction in mitochondria-derived DAMPs. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 306, H882–H894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatson, J.W.; Maass, D.L.; Simpkins, J.W.; Idris, A.H.; Minei, J.P.; Wigginton, J.G. Estrogen treatment following severe burn injury reduces brain inflammation and apoptotic signaling. J. Neuroinflamm. 2009, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Ozhathil, D.K.; El Ayadi, A.; Golovko, G.; Wolf, S.E. C-reactive protein elevation is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in elderly burned patients. Burns 2023, 49, 806–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, K.; Faraklas, I.; Lewis, G.; Ha, D.; Walker, B.; Zhai, Y.; Graves, G.; Dissanaike, S. Increased mortality in women: Sex differences in burn outcomes. Burn. Trauma 2017, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, N.N.; Hung, N.T.; Duc, N.M. Influence of gender difference on outcomes of adult burn patients in a developing country. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2019, 32, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, P.K.; Agarwal, M. Postmenopausal syndrome. Indian J. Psychiatry 2015, 57 (Suppl. S2), S222–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Rizzi, N.; Vegeto, E.; Ciana, P.; Maggi, A. Estrogen accelerates the resolution of inflammation in macrophagic cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D.S.; Fischer Sigel, L.K.; Azurmendi, P.J.; Vlachovsky, S.G.; Oddo, E.M.; Armando, I.; Ibarra, F.R.; Silberstein, C. Estradiol stimulates cell proliferation via classic estrogen receptor-alpha and G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1 in human renal tubular epithelial cell primary cultures. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 512, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.; Sheriff, S.; Faroqui, R.; Siddiqui, F.; Hawse, J.R.; Amlal, H. Klotho/fibroblast growth factor 23- and PTH-independent estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated direct downregulation of NaPi-IIa by estrogen in the mouse kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2016, 311, F249–F259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugarten, J.; Golestaneh, L. Female sex reduces the risk of hospital-associated acute kidney injury: A meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksen, B.O.; Ingebretsen, O.C. The progression of chronic kidney disease: A 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, M.; Clark, A.T.; Neyra, J.A.; Ostermann, M. Acute kidney injury in patients with burns. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2023, 20, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Neyra, J.A.; Madni, T.; Imran, J.; Phelan, H.; Arnoldo, B.; Wolf, S.E. Acute kidney injury after burn. Burns 2017, 43, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gong, Y.; Chen, J.; Yuan, L.; Luo, G.; Peng, Y.; Yuan, Z. Late-Onset Acute Kidney Injury is a Poor Prognostic Sign for Severe Burn Patients. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 842999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodis, H.N. Assessing benefits and risks of hormone therapy in 2008: New evidence, especially with regard to the heart. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2008, 75 (Suppl. S4), S3–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapking, C.; Popp, D.; Herndon, D.N.; Branski, L.K.; Hundeshagen, G.; Armenta, A.M.; Busch, M.; Most, P.; Kinsky, M.P. Cardiac Dysfunction in Severely Burned Patients: Current Understanding of Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Shock 2020, 53, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, T.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Huang, M.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Su, Y.C. Increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with burn injury: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2016, 24, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, G.S.; Mills, S.J.; Lei, K.; Gibbons, L.; Jeong, M.J.; Taniguchi, M.; Burow, M.; Horan, M.A.; Wahl, S.M.; Nakayama, T. Estrogen modulates cutaneous wound healing by downregulating macrophage migration inhibitory factor. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, R.; Teixeira, D.; Calhau, C. Estrogen signaling in metabolic inflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 615917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Horike, S.I.; Meguro-Horike, M.; Nakajima, Y.; Iswara, A.; Nakatani, T. Topical estrogen application promotes cutaneous wound healing in db/db female mice with type 2 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, G.S.; Dodsworth, J.; van Boxtel, E.; Tarnuzzer, R.W.; Horan, M.A.; Schultz, G.S.; Ferguson, M.W. Estrogen accelerates cutaneous wound healing associated with an increase in TGF-β1 levels. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 1209–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, L.; Emmerson, E.; Davies, F.; Gilliver, S.C.; Krust, A.; Chambon, P.; Ashcroft, G.S.; Hardman, M.J. Estrogen promotes cutaneous wound healing via estrogen receptor beta independent of its antiinflammatory activities. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 1825–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, H.C.; Chang, W.H.; Yeh, C.C.; Huang, B.S.; Chang, C.P.; Chen, Y.J.; Tsui, K.H.; Wang, P.H. Estrogen Effects on Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.F.; Perez-Stable, E.J.; Whitaker, E.E.; Posner, S.F.; Alexander, M.; Gathe, J.; Washington, A.E. Ethnic differences in hormone replacement prescribing patterns. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1999, 14, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, S.D.; Burnett-Bowie, S.M.; Greendale, G.A.; Avis, N.E.; Reeves, A.N.; Richards, T.R.; Lewis, T.T. Disparities in Reproductive Aging and Midlife Health between Black and White women: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Women’s Midlife Health 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPaolo, N.; Hulsebos, I.F.; Yu, J.; Gillenwater, T.J.; Yenikomshian, H.A. Race and Ethnicity Influences Outcomes of Adult Burn Patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2023, 44, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeschke, M.G.; Patsouris, D.; Stanojcic, M.; Abdullahi, A.; Rehou, S.; Pinto, R.; Chen, P.; Burnett, M.; Amini-Nik, S. Pathophysiologic Response to Burns in the Elderly. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzensen, N.; Trabert, B. Hormone therapy: Short-term relief, long-term consequences. Lancet 2015, 385, 1806–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz Brinton, R. Minireview: Translational animal models of human menopause: Challenges and emerging opportunities. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 3571–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | No | Yes | ||||

| Patients | % of Cohort | Patients | % of Cohort | p-Value | ||

| 11816 | 2226 | |||||

| age [mean (SD)] | 60 (12) | 100 | 58 (12) | 100 | 1.0000 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 813 | 6.88 | 124 | 5.57 | 0.0260 | |

| Not Hispanic | 8887 | 75.21 | 1785 | 80.19 | 0.0001 | |

| Unknown | 2116 | 17.91 | 317 | 14.24 | 0.0001 | |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 47 | 0.40 | 8 | 0.36 | 0.9355 | |

| Asian | 258 | 2.18 | 37 | 1.66 | 0.1355 | |

| African American | 2015 | 17.05 | 248 | 11.14 | 0.0001 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 11 | 0.09 | 2 | 0.09 | 1.0000 | |

| Unknown | 1418 | 12.00 | 223 | 10.02 | 0.0084 | |

| White | 8067 | 68.27 | 1708 | 76.73 | 0.0001 | |

| Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | No | Yes | ||||

| Patients | % of Cohort | Patients | % of Cohort | p-Value | ||

| 12016 | 3237 | |||||

| age [mean (SD)] | 60(12) | 100 | 58 (12) | 100 | 1.0000 | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 854 | 7.11 | 187 | 5.78 | 0.0087 | |

| Not Hispanic | 9087 | 75.62 | 2558 | 79.02 | 0.0001 | |

| Unknown | 2075 | 17.27 | 492 | 15.20 | 0.0057 | |

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 46 | 0.38 | 11 | 0.34 | 0.8465 | |

| Asian | 258 | 2.15 | 54 | 1.67 | 0.1013 | |

| African American | 2066 | 17.19 | 382 | 11.80 | 0.0001 | |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 9 | 0.08 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.6150 | |

| Unknown | 1413 | 11.76 | 325 | 10.04 | 0.0069 | |

| White | 8224 | 68.44 | 2461 | 76.03 | 0.0001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, J.; Golovko, G.; Botnar, K.; El Ayadi, A.; Vincent, K.L.; Wolf, S.E. Estrogen Treatment Lowers the Risk of Complications in Menopausal Women with Mild Burn Injury. Medicina 2025, 61, 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020300

Song J, Golovko G, Botnar K, El Ayadi A, Vincent KL, Wolf SE. Estrogen Treatment Lowers the Risk of Complications in Menopausal Women with Mild Burn Injury. Medicina. 2025; 61(2):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020300

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Juquan, George Golovko, Kostiantyn Botnar, Amina El Ayadi, Kathleen L. Vincent, and Steven E. Wolf. 2025. "Estrogen Treatment Lowers the Risk of Complications in Menopausal Women with Mild Burn Injury" Medicina 61, no. 2: 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020300

APA StyleSong, J., Golovko, G., Botnar, K., El Ayadi, A., Vincent, K. L., & Wolf, S. E. (2025). Estrogen Treatment Lowers the Risk of Complications in Menopausal Women with Mild Burn Injury. Medicina, 61(2), 300. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020300