A Foreign Body as a Gynaecological and Sexological Issue—Case Study and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

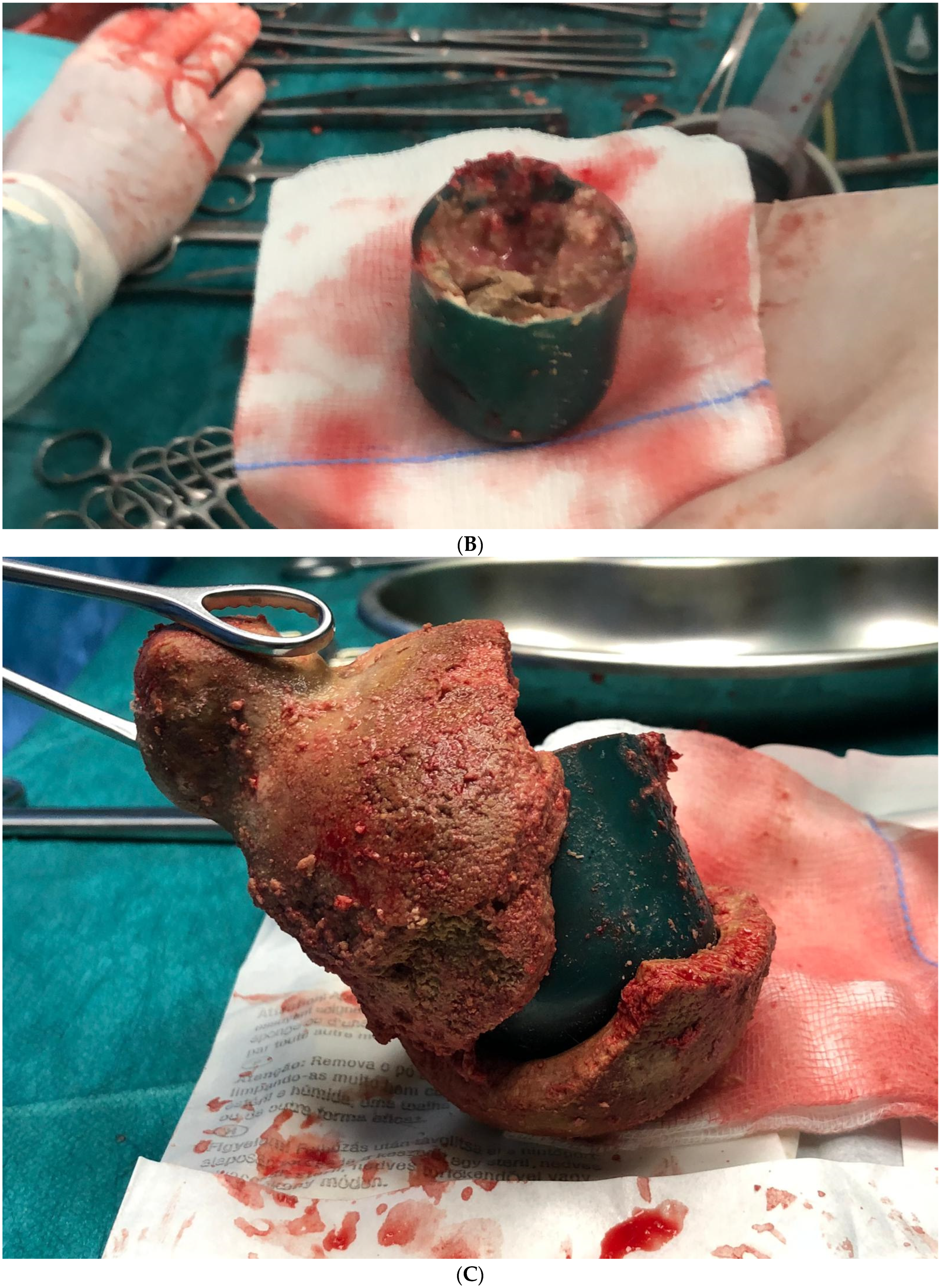

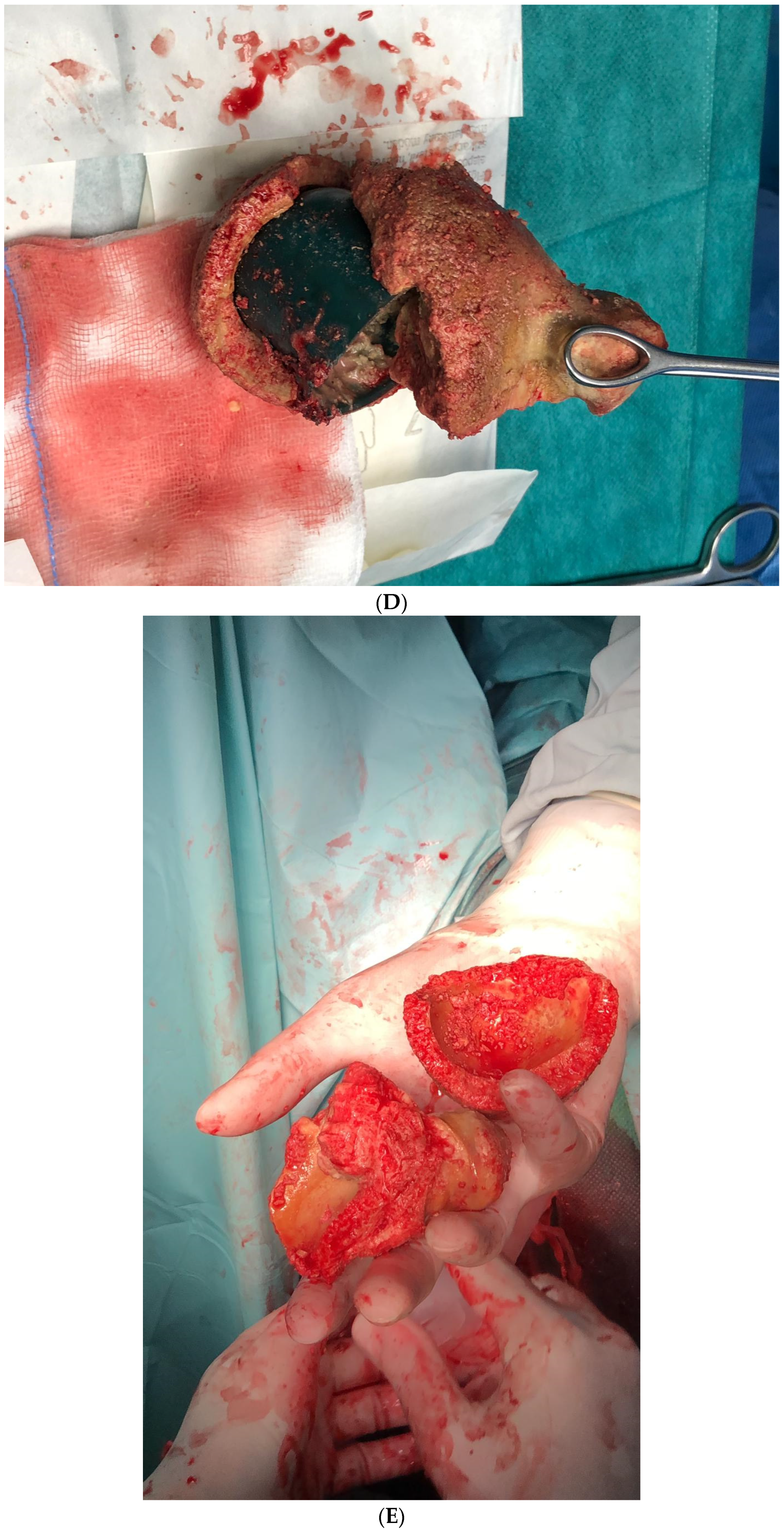

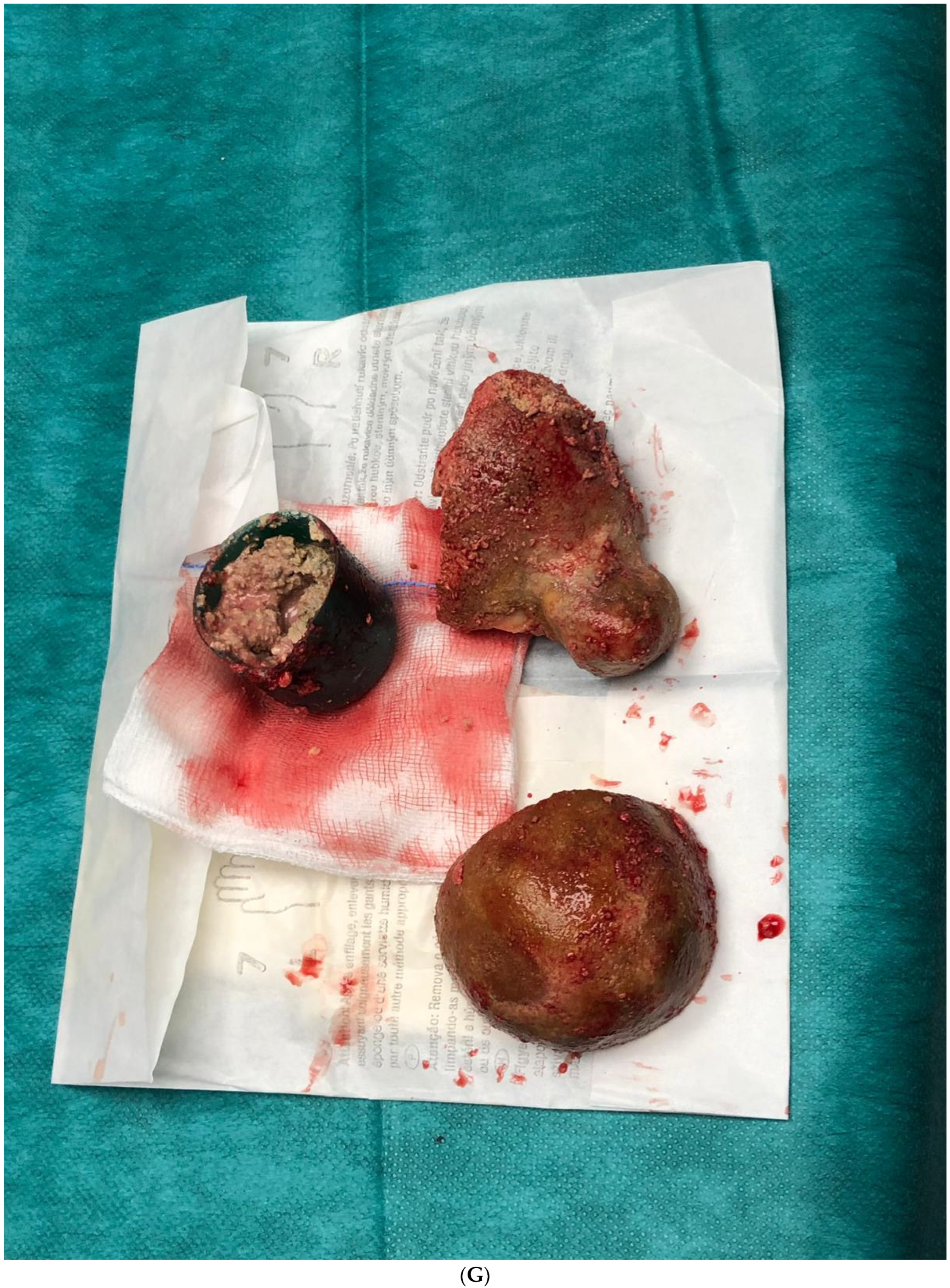

2. Case Study

Surgical Procedure

3. Discussion

4. Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ciebiera, M.; Słabuszewska-Jóźwiak, A.; Ledowicz, W.; Jakiel, G. Vaginal foreign body mimicking cervical cancer in postmenopausal woman—Case study. Menopause Rev./Przegląd Menopauzalny 2015, 3, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puppo, A.; Naselli, A.; Centurioni, M.G. Vesicovaginal fistula caused by a vaginal foreign body in a 72-year-old woman: Case report and literature review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2009, 20, 1387–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, S.; Singh, Y.; Magon, N. A case of intravaginal foreign body. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2010, 66, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umans, E.; Boogaerts, M.; Vergauwe, B.; Verest, A.; Van Calenbergh, S. Vaginal foreign body in the pediatric patient: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 297, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilton, P. Vesico-vaginal fistulas in developing countries. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2003, 82, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, M.; Baum, E.; Lewandowska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Dolińska-Kaczmarek, K.; Englert-Golon, M. A Unique Glassy Cell Carcinoma (GCC) of the Cervix Diagnosed during Pregnancy—A Case Report. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Oufi, D.; Alkharboush, H.M.; Younis, N.D.; Abu-Zaid, A. Disk Battery as a Vaginal Foreign Body in a Five-Year-Old Preadolescent Child. Cureus 2021, 13, e13727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bermúdez, J.; Sánchez, M. Retained polyurethane foam in the vagina: A case report. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 33, 557–558. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Sun, L.; Ye, J.; Li, X.; Tao, R. Ultrasonography in Detection of Vaginal Foreign Bodies in Girls: A Retrospective Study. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2017, 30, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saidman, J.M.; Bertoni, V.; Demeco, C.M.; Padilla, M.L.; Ormaechea, M.N.; Chacon, C.R.B.; Kreindel, T.G. Importance of Doppler ultrasound in vaginal foreign body: Case report and review of the literature. J. Ultrasound 2022, 25, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Itriyeva, K. Evaluation of vulvovaginitis in the adolescent patient. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Heal. Care 2020, 50, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, R.; Rottenstreich, A.; Mohr-Sasson, A.; Dori-Dayan, N.; Toren, A.; Levin, G. Tampon loss—Management among adolescents and adult women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 41, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanowski, B.; Kucharski, M.; Szeliga, A.; Snopek, M.; Kostrzak, A.; Smolarczyk, R.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M.; Duszewska, A.; Niwczyk, O.; Drozd, S.; et al. Cognitive decline and dementia in women after menopause: Prevention strategies. Maturitas 2023, 168, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mędrala, W.; Rodek, P.; Alli-Balogun, B.; Barabasz-Gembczyk, A.; Wójcik, P.; Kucia, K. Malignant complications of masturbation—A case study. Psychiatr. Pol. 2023, 57, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Vegda, D.S.; Vishwa SGandhi, V.S. Vaginal Foreign Body Forgotten for 20 Years in a Postmenopausal Female: A Case Report. Cureus 2022, 14, e33132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Witchel, S.F.; Sanfilippo, J.S. Vaginal foreign body: A delayed diagnosis. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2014, 27, e127–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasari, P.; Sagili, H. Incarcerated foreign body in the vagina—A metal bangle used as a pessary. BMJ Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr0120125596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dwiggins, M.; Gomez-Lobo, V. Current review of prepubertal vaginal bleeding. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 29, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plagens-Rotman, K.; Merks, P.; Pisarska-Krawczyk, M.; Bojanowska, K.; Jaguszewska, E.; Lewek, A.; Madziar, K.; Kapczuk, K.; Goździewicz, T.; Guszczyńska-Losy, M.; et al. Cervical Cancer Prevention: The Role of the Nurse and Medical Care in Primary and Secondary Cancer Prevention. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 50, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancati, A.; Crudele, G.D.; Gentile, G.; Zoja, R. The case of a prosthetic limb used to cause lethal intravaginal injuries: Forensic medical aspects in a case of intimate partner violence. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 234, e21–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengistu, Z.; Ayichew, Z. Large Vesicovaginal Fistula After Vaginal Insertion of a Plastic Cap Healed with Two Weeks of Catheterization: A Case Report. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2022, 15, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Irumba, C.; Baragaine, J.; Obore, S.; Mwanje, H.; Nteziyaremye, J. An intricate vagina penetrating injury with a 22 cm cassava stick in situ for 6 months: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2024, 18, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nkwabong, E.; Fomulu, J.N. Urethrovaginal fistula following vaginal prolapse of a pedunculated uterine myoma: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2017, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ovadia, J.; Reichman, J.; Goldman, J.A. Secondary cervical perforation by the Copper-T intrauterine device. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1979, 9, 403–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warraich, H.S.A.; Younis, Z.; Warraich, J.; Shaukat Ali, A.; Warraich, K. A Self-Induced Foreign Body in the Urinary Bladder of an Adolescent Female. Cureus 2024, 16, e61811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilczak, M.; Samulak, D.; Englert-Golon, M.; Pieta, B. Clinical usefulness of evaluation of quality parameters of blood flow: Pulsation index and resistance index in the uterine arteries in the initial differential diagnostics of pathology within the endometrium. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2010, 31, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frąckowiak, A.; Sajdak, S.; Jarząbek-Bielecka, G.; Dolińska-Kaczmarek, K.; Plagens-Rotman, K.; Merks, P.; Kościński, T.; Englert-Golon, M. A Foreign Body as a Gynaecological and Sexological Issue—Case Study and Literature Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020290

Frąckowiak A, Sajdak S, Jarząbek-Bielecka G, Dolińska-Kaczmarek K, Plagens-Rotman K, Merks P, Kościński T, Englert-Golon M. A Foreign Body as a Gynaecological and Sexological Issue—Case Study and Literature Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(2):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020290

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrąckowiak, Aleksander, Stefan Sajdak, Grażyna Jarząbek-Bielecka, Klaudia Dolińska-Kaczmarek, Katarzyna Plagens-Rotman, Piotr Merks, Tomasz Kościński, and Monika Englert-Golon. 2025. "A Foreign Body as a Gynaecological and Sexological Issue—Case Study and Literature Review" Medicina 61, no. 2: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020290

APA StyleFrąckowiak, A., Sajdak, S., Jarząbek-Bielecka, G., Dolińska-Kaczmarek, K., Plagens-Rotman, K., Merks, P., Kościński, T., & Englert-Golon, M. (2025). A Foreign Body as a Gynaecological and Sexological Issue—Case Study and Literature Review. Medicina, 61(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61020290