Proteomic Insights into the Retinal Response to PRGF in a Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental AMD Animal Model and Study Treatments

2.2. PRGF Preparation

2.3. Retinal Tissue Collection

2.4. Protein Extraction

2.5. Sample Preparation

2.6. Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.7. Protein Identification and Quantification

2.8. Functional Analysis

3. Results

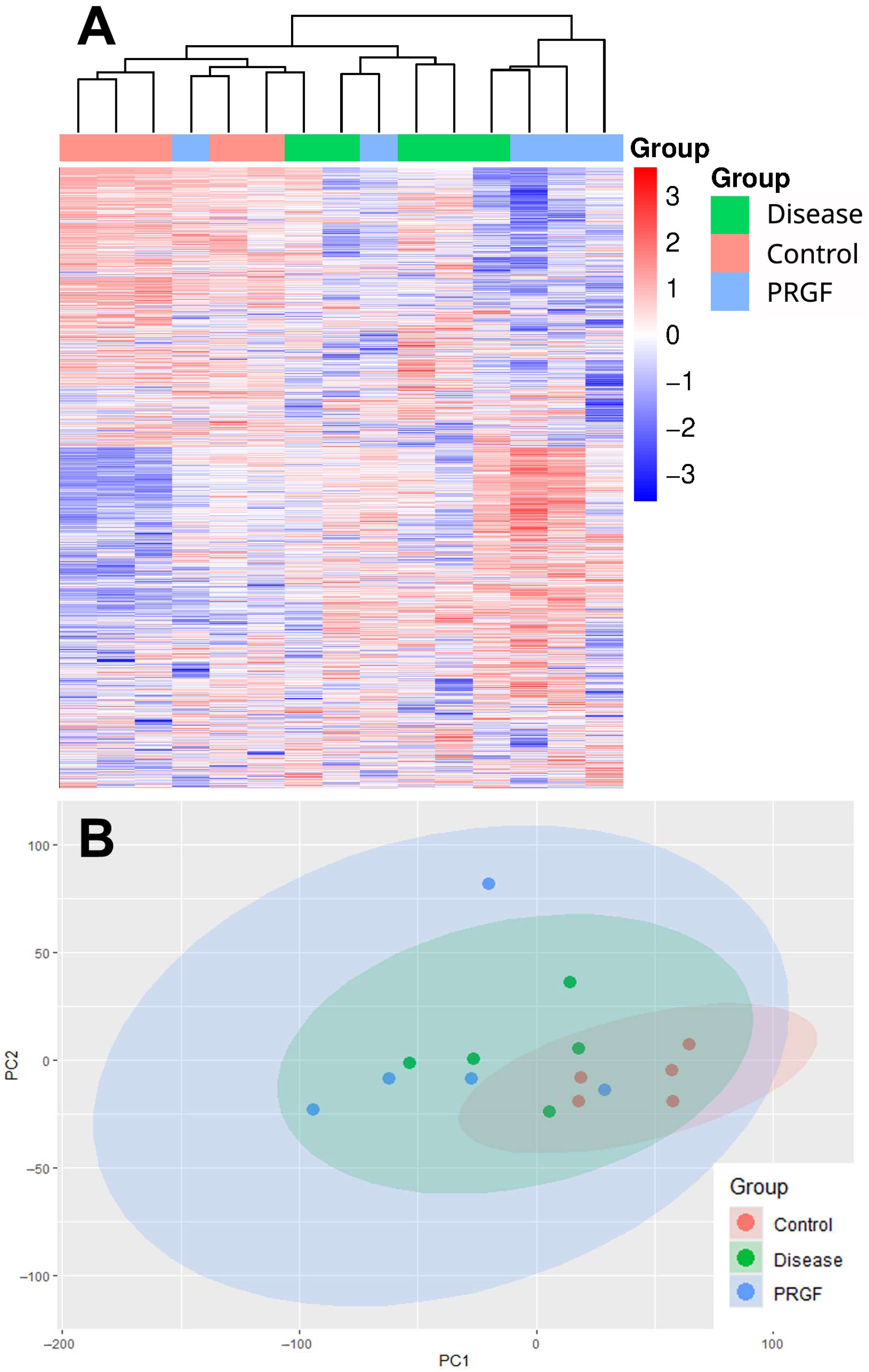

3.1. Protein Profile Evaluation

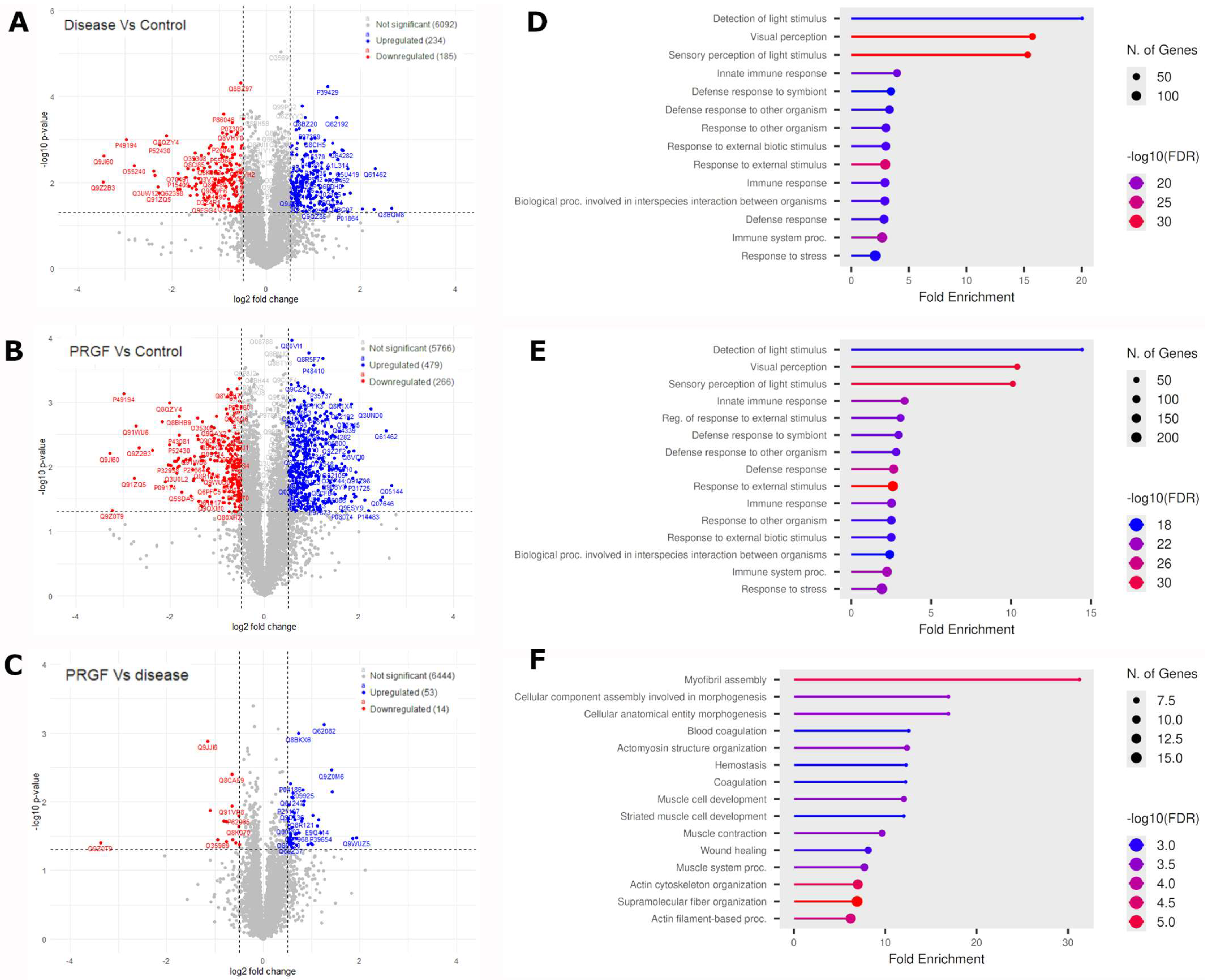

3.2. Differential Protein Analysis

3.3. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| CB-PRP | Cord blood-derived platelet-rich plasma |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| FA | Formic acid |

| FASP | Filter-aided sample preparation |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| GA | Geographic atrophy |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| IPA | Ingenuity pathway analysis |

| NaIO3 | Sodium iodate |

| nAMD | Neovascular AMD |

| PASEF | Parallel accumulation serial fragmentation |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PRGF | Plasma rich in growth factors |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| α-SMA | Alpha-smooth muscle actin |

References

- Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study; Blindness, G.B.D.; Vision Impairment, C. Global estimates on the number of people blind or visually impaired by age-related macular degeneration: A meta-analysis from 2000 to 2020. Eye 2024, 38, 2070–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, L.G.; Igl, W.; Bailey, J.N.; Grassmann, F.; Sengupta, S.; Bragg-Gresham, J.L.; Burdon, K.P.; Hebbring, S.J.; Wen, C.; Gorski, M.; et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, C.J.; Webster, A.R.; Snieder, H.; Bird, A.C.; Gilbert, C.E.; Spector, T.D. Genetic influence on early age-related maculopathy: A twin study. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.S.; Chee, Y.E.; Saraf, S.S.; Chew, E.Y.; Lee, C.S.; Lee, A.Y.; Manookin, M.B. Association of Environmental Factors with Age-Related Macular Degeneration using the Intelligent Research in Sight Registry. Ophthalmol. Sci 2022, 2, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, F.L., 3rd; Wilkinson, C.P.; Bird, A.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.; Csaky, K.; Sadda, S.R. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadda, S.R.; Guymer, R.; Holz, F.G.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Curcio, C.A.; Bird, A.C.; Blodi, B.A.; Bottoni, F.; Chakravarthy, U.; Chew, E.Y.; et al. Consensus Definition for Atrophy Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration on OCT: Classification of Atrophy Report 3. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armento, A.; Ueffing, M.; Clark, S.J. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 4487–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Cano, M.; Ebrahimi, K.; Wang, L.; Handa, J.T. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, D.Y.; Butcher, E.; Saint-Geniez, M. EMT and EndMT: Emerging Roles in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Koskela, A.; Blasiak, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Autophagy in drusen biogenesis secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.S.; Grossi, F.V.; El Mehdi, D.; Gerber, M.R.; Brown, D.M.; Heier, J.S.; Wykoff, C.C.; Singerman, L.J.; Abraham, P.; Grassmann, F.; et al. Complement C3 Inhibitor Pegcetacoplan for Geographic Atrophy Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Ophthalmology 2020, 127, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Sugita, S.; Kurimoto, Y.; Takahashi, M. Trends of Stem Cell Therapies in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Qiao, L.; Du, M.; Qu, C.; Wan, L.; Li, J.; Huang, L. Age-related macular degeneration: Epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and targeted therapy. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarkanova, D.; Cox, S.; Hernandez, D.; Rodriguez, L.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Madrigal, A.; Querol, S. Cord Blood Platelet Rich Plasma Derivatives for Clinical Applications in Non-transfusion Medicine. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykov, A.P.; Poveshchenk, O.V.; Surovtseva, M.A.; Stanishevskaya, O.M.; Chernykh, D.V.; Arben’eva, N.S.; Bratko, V.I. Autologous Plasma Enriched with Platelet Lysate for the Treatment of Idiopathic Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Prospective Study. Ann. Russ. Acad. Med. Sci. 2018, 73, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, S.; Savastano, M.C.; Falsini, B.; Bernardinelli, P.; Boselli, F.; De Vico, U.; Carlà, M.M.; Giannuzzi, F.; Fossataro, C.; Gambini, G.; et al. Safety Results for Geographic Atrophy Associated with Age-Related Macular Degeneration Using Subretinal Cord Blood Platelet-Rich Plasma. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, M.C.; Teofili, L.; Rizzo, S. Intravitreal cord-blood platelet-rich plasma for dry-AMD: Safety profile. AJO Int. 2024, 1, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, M.C.; Fossataro, C.; Berni, A.; Savastano, A.; Cestrone, V.; Giannuzzi, F.; Boselli, F.; Carlà, M.M.; Cusato, M.; Mottola, F.; et al. Intravitreal Injections of Cord Blood Platelet-Rich Plasma in Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Regenerative Therapy. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 5, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitua, E. Plasma rich in growth factors: Preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1999, 14, 529–535. [Google Scholar]

- Anitua, E.; Zalduendo, M.M.; Prado, R.; Alkhraisat, M.H.; Orive, G. Morphogen and proinflammatory cytokine release kinetics from PRGF-Endoret fibrin scaffolds: Evaluation of the effect of leukocyte inclusion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Muruzabal, F.; Recalde, S.; Fernandez-Robredo, P.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Potential Use of Plasma Rich in Growth Factors in Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Evidence from a Mouse Model. Medicina 2024, 60, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, C.; van den Hurk, K.T.; Ten Brink, J.B.; Lewallen, C.F.; Stanzel, B.V.; Bharti, K.; Bergen, A.A. Sodium-Iodate Injection Can Replicate Retinal Degenerative Disease Stages in Pigmented Mice and Rats: Non-Invasive Follow-Up Using OCT and ERG. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.E.; Alsaeedi, H.A.; Rashid, M.B.A.; Lam, C.; Harun, M.H.N.; Saleh, M.; Luu, C.D.; Kumar, S.S.; Ng, M.H.; Isa, H.M.; et al. Retinal degeneration rat model: A study on the structural and functional changes in the retina following injection of sodium iodate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 196, 111514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, J.R.; Zougman, A.; Nagaraj, N.; Mann, M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: Neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrazzaq, G.M.; Merkhan, M.M.; Billa, N.; Alany, R.G.; Amoaku, W.M.; Tint, N.L.; Ahmad, Z.; Qutachi, O. Current and emerging therapies for dry and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2025, 30, 1147–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.J.; Mirza, R.G.; Gill, M.K. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 105, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardue, M.T.; Allen, R.S. Neuroprotective strategies for retinal disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 65, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basyal, D.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.J. Antioxidants and Mechanistic Insights for Managing Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlingemann, R.O. Role of growth factors and the wound healing response in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2004, 242, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutto, I.A.; McLeod, D.S.; Hasegawa, T.; Kim, S.Y.; Merges, C.; Tong, P.; Lutty, G.A. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in aged human choroid and eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2006, 82, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Plandolit, S.; Morales, M.C.; Freire, V.; Etxebarria, J.; Duran, J.A. Plasma rich in growth factors as a therapeutic agent for persistent corneal epithelial defects. Cornea 2010, 29, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Nurden, P.; Prado, R.; Nurden, A.T.; Padilla, S. Autologous fibrin scaffolds: When platelet- and plasma-derived biomolecules meet fibrin. Biomaterials 2019, 192, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Barrio, C.; Del Olmo-Aguado, S.; Garcia-Perez, E.; de la Fuente, M.; Muruzabal, F.; Anitua, E.; Baamonde-Arbaiza, B.; Fernandez-Vega-Cueto, L.; Fernandez-Vega, L.; Merayo-Lloves, J. Antioxidant Role of PRGF on RPE Cells after Blue Light Insult as a Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; de la Fuente, M.; Del Olmo-Aguado, S.; Suarez-Barrio, C.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Muruzabal, F. Plasma rich in growth factors reduces blue light-induced oxidative damage on retinal pigment epithelial cells and restores their homeostasis by modulating vascular endothelial growth factor and pigment epithelium-derived factor expression. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 48, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsu, T.; Nagata, A.; Chiba, T.; Miyata, Y. Reduction of Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 levels in retinal pigment epithelial cells induces inflammation and inhibits autophagy flux: Pathology of age-related macular degeneration. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 43, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrington, D.A.; Fisher, C.R.; Kowluru, R.A. Mitochondrial Defects Drive Degenerative Retinal Diseases. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feher, J.; Kovacs, I.; Artico, M.; Cavallotti, C.; Papale, A.; Balacco Gabrieli, C. Mitochondrial alterations of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S. Role of Mitochondria in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Aging and Degeneration. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 926627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenin, R.R.; Koh, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.; Yeo, Y.Z.; Parikh, B.H.; Seah, I.; Wong, W.; Su, X. Dysfunctional Autophagy, Proteostasis, and Mitochondria as a Prelude to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashijima, F.; Hasegawa, M.; Yoshimoto, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Wakuta, M.; Kimura, K. Molecular mechanisms of TGFβ-mediated EMT of retinal pigment epithelium in subretinal fibrosis of age-related macular degeneration. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 1060087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, B. Myofibroblasts. Exp. Eye Res. 2016, 142, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Sang, X.; Liu, J.; Su, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; et al. Autophagy Dysfunction, Cellular Senescence, and Abnormal Immune-Inflammatory Responses in AMD: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Potential. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3632169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.C.; Ma, J.Y.W.; Jobling, A.I.; Brandli, A.; Greferath, U.; Fletcher, E.L.; Vessey, K.A. Exploring the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration: A review of the interplay between retinal pigment epithelium dysfunction and the innate immune system. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1009599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enzbrenner, A.; Zulliger, R.; Biber, J.; Pousa, A.M.Q.; Schäfer, N.; Stucki, C.; Giroud, N.; Berrera, M.; Kortvely, E.; Schmucki, R.; et al. Sodium Iodate-Induced Degeneration Results in Local Complement Changes and Inflammatory Processes in Murine Retina. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karema-Jokinen, V.; Koskela, A.; Hytti, M.; Hongisto, H.; Viheriälä, T.; Liukkonen, M.; Torsti, T.; Skottman, H.; Kauppinen, A.; Nymark, S.; et al. Crosstalk of protein clearance, inflammasome, and Ca2+ channels in retinal pigment epithelium derived from age-related macular degeneration patients. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maceroni, E.; Cimini, A.; Quintiliani, M.; d’Angelo, M.; Castelli, V. Retinal Gatekeepers: Molecular Mechanism and Therapeutic Role of Cysteine and Selenocysteine. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korwar, A.M.; Hossain, A.; Lee, T.J.; Shay, A.E.; Basrur, V.; Conlon, K.; Smith, P.B.; Carlson, B.A.; Salis, H.M.; Patterson, A.D.; et al. Selenium-dependent metabolic reprogramming during inflammation and resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyong, E.N.; Gurley, J.M.; De Ieso, M.L.; Stamer, W.D.; Elliott, M.H. Caveolar and non-Caveolar Caveolin-1 in ocular homeostasis and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 91, 101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Litwin, C.; Cheng, R.; Ma, J.X.; Chen, Y. DARPP32, a target of hyperactive mTORC1 in the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207489119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klevay, L.M. Calcium can delay age-related macular degeneration via enhanced copper metabolism. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 135, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, O.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Luo, P. Association between age-related macular degeneration and osteoporosis in US. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T.A.; Wang, C.T.; Colicos, M.A.; Zaccolo, M.; DiPilato, L.M.; Zhang, J.; Tsien, R.Y.; Feller, M.B. Imaging of cAMP levels and protein kinase A activity reveals that retinal waves drive oscillations in second-messenger cascades. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 12807–12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes de Faria, J.M.; Duarte, D.A.; Simó, R.; García-Ramirez, M.; Dátilo, M.N.; Pasqualetto, F.C.; Lopes de Faria, J.B. δ Opioid Receptor Agonism Preserves the Retinal Pigmented Epithelial Cell Tight Junctions and Ameliorates the Retinopathy in Experimental Diabetes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 3842–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, J.J.; Starr, C.R.; Lee, E.J.; Park, K.S.; Zhylkibayev, A.; Medina, A.; Lin, J.H.; Gorbatyuk, M. The endoplasmic reticulum: Homeostasis and crosstalk in retinal health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 98, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, H.; Paldanius, K.M.A.; Natunen, T.; Takalo, M.; Marttinen, M.; Leskelä, S.; Huber, N.; Mäkinen, P.; Bertling, E.; Dhungana, H.; et al. DHCR24 exerts neuroprotection upon inflammation-induced neuronal death. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Ismail, E.N.; Yao, P.L.; Tayyari, F.; Radu, R.A.; Nusinowitz, S.; Boulton, M.E.; Apte, R.S.; Ruberti, J.W.; Handa, J.T.; et al. LXRs regulate features of age-related macular degeneration and may be a potential therapeutic target. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e131928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Canonical Pathways | −log(p-Value) | z-Score | Related Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil degranulation | 33.20 | 5.67 | Inflammation |

| Visual phototransduction | 23.10 | −5.21 | - |

| Signaling by Rho Family GTPases | 17.00 | 2.80 | Fibrosis |

| EIF2 signaling | 16.50 | 3.40 | Oxi. Stress |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation | 15.50 | 6.08 | Cel. Stress |

| Selenoamino acid metabolism | 15.10 | 5.33 | Oxi. Stress |

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 14.80 | 5.92 | - |

| Response of EIF2AK4 (GCN2) to amino acid deficiency | 14.20 | 5.39 | Cel. Stress |

| Eukaryotic translation elongation | 13.60 | 5.57 | Protein Metab. |

| Nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) | 13.40 | 5.48 | Protein Metab. |

| Signaling by ROBO receptors | 13.30 | 2.32 | Angiogenesis |

| Mitochondrial protein degradation | 13.00 | −4.54 | Energy Metab. |

| Sirtuin signaling pathway | 11.90 | 2.12 | Angiogenesis |

| Ribosomal quality control signaling pathway | 11.50 | 5.34 | Protein Metab. |

| Regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling | 11.50 | 2.65 | Oxi. Stress |

| Class I MHC mediated antigen processing and presentation | 11.40 | 5.08 | Inflammation |

| Eukaryotic translation termination | 11.30 | 5.29 | Protein Metab. |

| RHO GTPase cycle | 10.90 | 4.13 | Fibrosis |

| IL-8 Signaling | 10.80 | 3.05 | Inflammation |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | 10.60 | 3.36 | Energy Metab. |

| Major pathway of rRNA processing in the nucleolus and cytosol | 10.30 | 5.15 | Protein Metab. |

| CLEAR signaling pathway | 9.29 | 2.59 | Cel. Stress |

| Coronavirus pathogenesis pathway | 8.78 | −2.56 | - |

| Protein ubiquitination pathway | 8.54 | 2.14 | Protein Metab. |

| Cristae formation | 8.31 | −3.61 | Energy Metab. |

| Canonical Pathways | −log(p-Value) | z-Score | Related Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil Degranulation | 38.60 | 5.44 | Inflammation |

| Signaling by Rho Family GTPases | 24.00 | 2.29 | Fibrosis |

| RHO GTPase Cycle | 23.40 | 4.08 | Fibrosis |

| Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling | 23.30 | 4.18 | Fibrosis |

| Visual Phototransduction | 23.10 | −5.58 | - |

| RHOGDI Signaling | 21.60 | −2.21 | Fibrosis |

| Integrin Signaling | 15.10 | 3.61 | Inflammation |

| Class I MHC Mediated Antigen Processing and Presentation | 13.30 | 3.16 | Inflammation |

| Remodeling of Epithelial Adherens Junctions | 13.20 | 2.11 | Homeostasis |

| EIF2 Signaling | 12.10 | 3.13 | Oxi. stress |

| Regulation of Actin-based Motility by Rho | 12.10 | 2.75 | Fibrosis |

| ILK Signaling | 11.40 | 2.97 | Fibrosis |

| Striated Muscle Contraction | 10.80 | 4.24 | Fibrosis |

| RAC Signaling | 10.60 | 3.02 | Angiogenesis |

| Response to Elevated Platelet Cytosolic Ca2+ | 10.50 | 4.90 | Homeostasis |

| Selenoamino Acid Metabolism | 10.40 | 4.11 | Homeostasis |

| fMLP Signaling in Neutrophils | 9.72 | 2.12 | Inflammation |

| CXCR4 Signaling | 9.68 | 2.19 | Inflammation |

| Caveolar-mediated Endocytosis Signaling | 9.44 | 2.18 | Homeostasis |

| Fcγ Receptor-mediated Phagocytosis in Macrophages and Monocytes | 9.19 | 3.27 | Inflammation |

| Paxillin Signaling | 9.14 | 2.29 | Fibrosis |

| Gluconeogenesis I | 9.12 | −2.31 | Energy Metab. |

| Thrombin Signaling | 8.93 | 2.41 | Inflammation |

| Eukaryotic Translation Initiation | 8.83 | 5.58 | Cel. Stress |

| Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling | 8.82 | 3.89 | Inflammation |

| Canonical Pathways | −log(p-Value) | z-Score | Related Processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Striated Muscle Contraction | 11.20 | 3.16 | Cel migration |

| Calcium Signaling | 11.10 | −2.12 | Inflammation, lipofucsin accumulation, and fibrosis |

| Protein Kinase A Signaling | 10.50 | −2.14 | Homeostasis |

| Opioid Signaling | 8.21 | −2.71 | Homeostasis |

| MHC class II Antigen Presentation | 7.58 | −3.46 | Inflammation |

| LXR/RXR Activation | 7.51 | 2.83 | Homeostasis |

| DHCR24 Signaling Pathway | 7.05 | 2.53 | Homeostasis |

| Dilated Cardiomyopathy Signaling Pathway | 6.79 | −3.32 | Fibrosis |

| Response to Elevated Platelet Cytosolic Ca2+ | 5.56 | 2.53 | - |

| Hepatic Fibrosis Signaling Pathway | 5.21 | 2.50 | Fibrosis |

| Dopamine-DARPP32 Feedback in cAMP Signaling | 5.20 | −2.11 | Fibrosis and RPE degeneration |

| Semaphorin Neuronal Repulsive Signaling Pathway | 5.14 | 2.33 | Angiogenesis |

| Smooth Muscle Contraction | 5.07 | 2.45 | Fibrosis |

| Nuclear Cytoskeleton Signaling Pathway | 5.04 | −2.31 | Fibrosis |

| Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Signaling | 4.94 | −2.33 | Inflammation and stress |

| Intra-Golgi and Retrograde Golgi-to-ER Traffic | 4.64 | −2.71 | Protein Metab. |

| Eicosanoid Signaling | 4.01 | −2.11 | Oxi. stress |

| Post-translational Protein Phosphorylation | 3.66 | 2.65 | - |

| Integration of Energy Metabolism | 3.63 | −2.65 | Energy Metab. |

| HSP90 Chaperone Cycle for Steroid Hormone Receptors in the Presence of Ligand | 3.33 | −2.24 | Cel. stress |

| Ephrin Receptor Signaling | 3.29 | −2.12 | Angiogenesis |

| Regulation of Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Transport and Uptake by IGFBPs | 3.27 | 2.65 | Angiogenesis |

| Synaptic Long-Term Potentiation | 3.27 | −2.65 | - |

| Kinesins | 3.16 | −2.24 | Protein Metab. |

| Formation of Fibrin Clot (Clotting Cascade) | 3.01 | 2.00 | Fibrosis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anitua, E.; Muruzabal, F.; Recalde, S.; de la Fuente, M.; Reparaz, I.; Azkargorta, M.; Elortza, F.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Proteomic Insights into the Retinal Response to PRGF in a Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Medicina 2025, 61, 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122235

Anitua E, Muruzabal F, Recalde S, de la Fuente M, Reparaz I, Azkargorta M, Elortza F, Alkhraisat MH. Proteomic Insights into the Retinal Response to PRGF in a Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122235

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnitua, Eduardo, Francisco Muruzabal, Sergio Recalde, María de la Fuente, Iraia Reparaz, Mikel Azkargorta, Félix Elortza, and Mohammad Hamdan Alkhraisat. 2025. "Proteomic Insights into the Retinal Response to PRGF in a Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122235

APA StyleAnitua, E., Muruzabal, F., Recalde, S., de la Fuente, M., Reparaz, I., Azkargorta, M., Elortza, F., & Alkhraisat, M. H. (2025). Proteomic Insights into the Retinal Response to PRGF in a Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Medicina, 61(12), 2235. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122235