From Echo to Coronary Angiography: Optimizing Ischemia Evaluation Through Multimodal Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objective

3. Materials and Methods

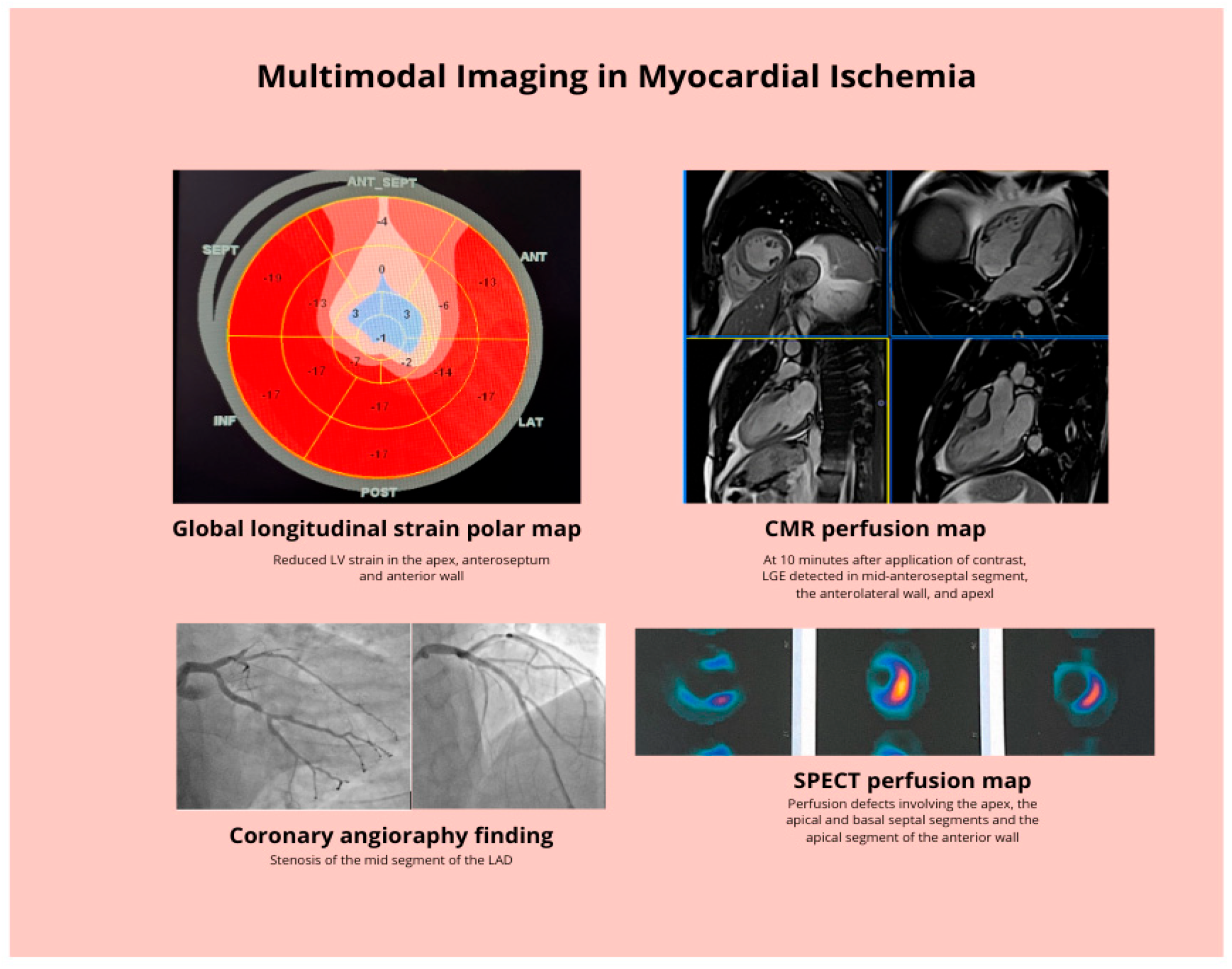

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

4. Rationale for a Multimodal Strategy

5. Echocardiography in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

Practical Considerations and Integration of Echocardiography into Multimodal Strategy

6. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

Practical Considerations and Integration of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography into Multimodal Strategy

7. SPECT and PET in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

Practical Considerations and Integration of SPECT and PET into Multimodal Strategy

8. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

Practical Considerations and Integration of CMR into Multimodal Strategy

9. Coronary Angiography and Intracoronary Imaging

Practical Considerations and Integration of Intracoronary Imaging in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

10. The Summary of Practical Implications and Patient Oriented Approach to Multimodality Imaging in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

11. The Future of Multimodal Imaging in the Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia

12. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naghavi, M.; Ong, K.L.; Aali, A.; Ababneh, H.S.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasgholizadeh, R.; Abbasian, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; et al. Global Burden of 288 Causes of Death and Life Expectancy Decomposition in 204 Countries and Territories and 811 Subnational Locations, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 833–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsen, T.; Asch, F.M.; Davidson, B.; Delgado, V.; DeMaria, A.; Dilsizian, V.; Gaemperli, O.; Garcia, M.J.; Kamp, O.; Lee, D.C.; et al. Non-Invasive Imaging in Coronary Syndromes: Recommendations of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging and the American Society of Echocardiography, in Collaboration With the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2022, 35, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zito, A.; Galli, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Abbate, A.; Douglas, P.S.; Princi, G.; D’aMario, D.; Aurigemma, C.; Romagnoli, E.; Trani, C.; et al. Diagnostic Strategies for the Assessment of Suspected Stable Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, R.; Morrow, A.J.; Stanley, B.; Ang, D.; Roditi, G.; Stobo, D.; Corcoran, D.; Lang, N.N.; Mahrous, A.; Young, R.; et al. Exercise Electrocardiography Stress Testing in Suspected Angina and Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2920–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, D.E.; Maron, D.J.; Blankstein, R.; Chang, I.C.; Kirtane, A.J.; Kwong, R.Y.; Pellikka, P.A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Russell, R.; Sandhu, A.T. ACC/AHA/ASE/ASNC/ASPC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2023 Multimodality Appropriate Use Criteria for the Detection and Risk Assessment of Chronic Coronary Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2445–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Polymeropoulos, A.; Baravelli, M.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M.; Biondi-Zoccai, G. Diagnostic Accuracy of Exercise Stress Testing, Stress Echocardiography, Myocardial Scintigraphy, and Cardiac Magnetic Resonance for Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of 104 Studies Published from 1990 to 2025. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leischik, R.; Dworrak, B.; Sanchis-Gomar, F.; Lucia, A.; Buck, T.; Erbel, R. Echocardiographic Assessment of Myocardial Ischemia. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiseth, O.A.; Torp, H.; Opdahl, A.; Haugaa, K.H.; Urheim, S. Myocardial Strain Imaging: How Useful Is It in Clinical Decision Making? Eur. Heart J. 2015, 37, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, N.; Iliopoulou, S.; Raptis, D.G.; Grammenos, O.; Kalaitzoglou, M.; Chrysikou, M.; Mantzios, C.; Theodorou, P.; Bostanitis, I.; Charisopoulou, D.; et al. Global Longitudinal Strain in Stress Echocardiography: A Review of Its Diagnostic and Prognostic Role in Noninvasive Cardiac Assessment. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steeds, R.P.; Wheeler, R.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Reiken, J.; Nihoyannopoulos, P.; Senior, R.; Monaghan, M.J.; Sharma, V. Stress Echocardiography in Coronary Artery Disease: A Practical Guideline from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res. Pract. 2019, 6, G17–G33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, R.; Becher, H.; Monaghan, M.; Agati, L.; Zamorano, J.; Vanoverschelde, J.L.; Nihoyannopoulos, P. Contrast Echocardiography: Evidence-Based Recommendations by European Association of Echocardiography. Eur. J. Echocardiogr. 2008, 10, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salame, G.; Juselius, W.E.; Burden, M.; Long, C.S.; Bendelow, T.; Beaty, B.; Masoudi, F.A.; Krantz, M.J. Contrast-Enhanced Stress Echocardiography and Myocardial Perfusion Imaging in Patients Hospitalized with Chest Pain: A Randomized Study. Crit. Pathw. Cardiol. J. Evid. Based Med. 2018, 17, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellikka, P.A.; Arruda-Olson, A.; Chaudhry, F.A.; Chen, M.H.; Marshall, J.E.; Porter, T.R.; Sawada, S.G. Guidelines for Performance, Interpretation, and Application of Stress Echocardiography in Ischemic Heart Disease: From the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 1–41.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Dow, S.; Shah, K.; Henkin, S.; Taub, C. Complications of Exercise and Pharmacologic Stress Echocardiography. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1228613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peteiro, J.; Bouzas-Mosquera, A. Complications of Exercise Echocardiography. Analysis of a Cohort of 19,239 Patients. Int. Cardiovasc. Forum J. 2017, 9, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Civieri, G.; Montisci, R.; Kerkhof, P.L.; Iliceto, S.; Tona, F. Coronary Flow Velocity Reserve by Echocardiography: Beyond Atherosclerotic Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Levy, P.D.; Mukherjee, D.; Amsterdam, E.; Bhatt, D.L.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blankstein, R.; Boyd, J.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Conejo, T.; et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 144, E368–E454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkriki, L.; Kleitsioti, P.; Dimitriadis, F.; Sidiropoulos, G.; Alkagiet, S.; Efstratiou, D.; Kalaitzoglou, M.; Charisopoulou, D.; Siarkos, M.; Mavrogianni, A.-D.; et al. The Utility of Low-Dose-Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: An Update. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.; King, G.; Murphy, R.T.; Walsh, D. Myocardial Strain: A Clinical Review. Ir. J. Med. Sci. (1971-) 2022, 192, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; D’aNdrea, A.; Sperlongano, S.; Tagliamonte, E.; Mandoli, G.E.; Santoro, C.; Evola, V.; Bandera, F.; Morrone, D.; Malagoli, A.; et al. Echocardiographic Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction: Basic Concepts, Technical Aspects, and Clinical Settings. Echocardiography 2021, 38, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Zanella, H.; Arbucci, R.; Fritche-Salazar, J.F.; Ortiz-Leon, X.A.; Tuttolomondo, D.; Lowenstein, D.H.; Wierzbowska-Drabik, K.; Ciampi, Q.; Kasprzak, J.D.; Gaibazzi, N.; et al. Vasodilator Strain Stress Echocardiography in Suspected Coronary Microvascular Angina. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, Y.; Kurata, A.; Matsuda, T.; Yoshida, K.; Baruah, D.; Kido, T.; Mochizuki, T.; Rajiah, P. Computed Tomographic Evaluation of Myocardial Ischemia. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2020, 38, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scot-Heart Investigators. Coronary CT Angiography and 5-Year Risk of Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, P.S.; Hoffmann, U.; Lee, K.L.; Mark, D.B.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Anstrom, K.; Dolor, R.J.; Kosinski, A.; Krucoff, M.W.; Mudrick, D.W.; et al. PROspective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain: Rationale and Design of the PROMISE Trial. Am. Heart J. 2014, 167, 796–803.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahman, K.M.; Chen, M.Y.; Dey, A.K.; Virmani, R.; Finn, A.V.; Khamis, R.Y.; Choi, A.D.; Min, J.K.; Williams, M.C.; Buckler, A.J.; et al. Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography from Clinical Uses to Emerging Technologies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serruys, P.W.; Kotoku, N.; Nørgaard, B.L.; Garg, S.; Nieman, K.; Dweck, M.R.; Bax, J.J.; Knuuti, J.; Narula, J.; Perera, D.; et al. Computed Tomographic Angiography in Coronary Artery Disease. EuroInterv. J. Eur. Collab. Work. Group Interv. Cardiol. Eur. Soc. Cardiol. 2023, 18, e1307–e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, C.-H.; Hung, C.-L.; Wen, M.-S.; Wan, Y.-L.; So, A. CT Assessment of Myocardial Perfusion and Fractional Flow Reserve in Coronary Artery Disease: A Review of Current Clinical Evidence and Recent Developments. Korean J. Radiol. 2021, 22, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Rochitte, C.E.; Arbab-Zadeh, A.; Dewey, M.; George, R.T.; Miller, J.M.; Niinuma, H.; Yoshioka, K.; Kitagawa, K.; Sakuma, H.; et al. Prognostic Value of Combined CT Angiography and Myocardial Perfusion Imaging versus Invasive Coronary Angiography and Nuclear Stress Perfusion Imaging in the Prediction of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events: The CORE320 Multicenter Study. Radiology 2017, 284, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontone, G.; Baggiano, A.; Andreini, D.; Guaricci, A.I.; Guglielmo, M.; Muscogiuri, G.; Fusini, L.; Fazzari, F.; Mushtaq, S.; Conte, E.; et al. Stress Computed Tomography Perfusion versus Fractional Flow Reserve CT Derived in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danad, I.; Szymonifka, J.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Norgaard, B.L.; Zarins, C.K.; Knaapen, P.; Min, J.K. Diagnostic Performance of Cardiac Imaging Methods to Diagnose Ischaemia-Causing Coronary Artery Disease When Directly Compared with Fractional Flow Reserve as a Reference Standard: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 38, ehw095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, F.; Klotz, E.; Flohr, T.; Becker, A.; Becker, L.; Berman, D.S.; Raff, G.; Hurwitz-Koweek, L.M.; Pontone, G.; Kawasaki, T.; et al. Real-World Clinical Utility and Impact on Clinical Decision-Making of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve: Lessons from the ADVANCE Registry. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3701–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Wragg, A.; Klotz, E.; Pirro, F.; Moon, J.C.; Nieman, K.; Pugliese, F. Dynamic Computed Tomography Myocardial Perfusion Imaging. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, e005505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nørgaard, B.L.; Leipsic, J.; Gaur, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Ko, B.S.; Ito, H.; Jensen, J.M.; Mauri, L.; De Bruyne, B.; Bezerra, H.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Noninvasive Fractional Flow Reserve Derived from Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in Suspected Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, P.S.; Pontone, G.; Hlatky, M.A.; Patel, M.R.; Norgaard, B.L.; Byrne, R.A.; Curzen, N.; Purcell, I.; Gutberlet, M.; Rioufol, G.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Fractional Flow Reserve by Computed Tomographic Angiography-Guided Diagnostic Strategies vs. Usual Care in Patients with Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: The Prospective Longitudinal Trial of FFRCT: Outcome and Resource Impacts Study. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 3359–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.C.; Weir-McCall, J.R.; Baldassarre, L.A.; De Cecco, C.N.; Choi, A.D.; Dey, D.; Dweck, M.R.; Isgum, I.; Kolossvary, M.; Leipsic, J.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (CCT): A White Paper of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT). J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2024, 18, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, C.; Carabetta, N.; Morano, M.B.; Manica, M.; Strangio, A.; Sabatino, J.; Leo, I.; Castagna, A.; Cianflone, E.; Torella, D.; et al. Understanding Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besutti, G.; Marvisi, C.; Mancuso, P.; Farì, R.; Monelli, F.; Revelli, M.; Durmo, R.; Galli, E.; Muratore, F.; Spaggiari, L.; et al. Prevalence and Distribution of Vascular Calcifications at CT Scan in Patients with and without Large Vessel Vasculitis: A Matched Cross-Sectional Study. RMD Open 2023, 9, e003278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanoudaki, V.C.; Ziegler, S.I. PET & SPECT Instrumentation. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2008, 185, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, R.; Celiker-Guler, E.; Rotstein, B.H.; deKemp, R.A. PET and SPECT Tracers for Myocardial Perfusion Imaging. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2020, 50, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, B.; Tägil, K.; Cuocolo, A.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Bardiés, M.; Bax, J.; Bengel, F.; Busemann Sokole, E.; Davies, G.; Dondi, M.; et al. EANM/ESC Procedural Guidelines for Myocardial Perfusion Imaging in Nuclear Cardiology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2005, 32, 855–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Kronenberg, M.W. Myocardial Perfusion and Viability Imaging in Coronary Artery Disease: Clinical Value in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Guidance. Am. J. Med. 2021, 134, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergamaschi, L.; Pavon, A.G.; Angeli, F.; Tuttolomondo, D.; Belmonte, M.; Armillotta, M.; Sansonetti, A.; Foà, A.; Paolisso, P.; Baggiano, A.; et al. The Role of Non-Invasive Multimodality Imaging in Chronic Coronary Syndrome: Anatomical and Functional Pathways. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soman, P.; Gropler, R.J.; deKemp, R.A. Absolute Myocardial Blood Flow Quantification with PET: Should Diagnostic Cutoffs Be Tracer Specific? Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, e018354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakano, S.; Gatate, Y.; Okano, N.; Muramatsu, T.; Nishimura, S.; Kuji, I.; Fukushima, K.; Matsunari, I. Feasibility of Simultaneous 99mTc-Tetrofosmin and 123I-BMIPP Dual-Tracer Imaging with Cadmium-Zinc-Telluride Detectors in Patients Undergoing Primary Coronary Intervention for Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Nucl. Cardiol. Off. Publ. Am. Soc. Nucl. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, T.; Utanohara, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Kurihara, M.; Iguchi, N.; Umemura, J.; Sumiyoshi, T.; Tomoike, H. A Preliminary Feasibility Study of Simultaneous Dual-Isotope Imaging with a Solid-State Dedicated Cardiac Camera for Evaluating Myocardial Perfusion and Fatty Acid Metabolism. Heart Vessel. 2014, 31, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, M.; Kamani, C.H.; Allenbach, G.; Rubimbura, V.; Fournier, S.; Dunet, V.; Treglia, G.; Lalonde, M.N.; Schaefer, N.; Eeckhout, E.; et al. Comparison of the Prognostic Value of Impaired Stress Myocardial Blood Flow, Myocardial Flow Reserve, and Myocardial Flow Capacity on Low-Dose Rubidium-82 SiPM PET/CT. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2022, 30, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubrey, R.O.; Mason, S.M.; Le, V.T.; Bride, D.L.; Horne, B.D.; Meredith, K.G.; Sekaran, N.K.; Anderson, J.L.; Knowlton, K.U.; Min, D.B.; et al. A Highly Predictive Cardiac Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Risk Score for 90-Day and One-Year Major Adverse Cardiac Events and Revascularization. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileva, N.; Nagumo, S.; Mizukami, T.; Sonck, J.; Berry, C.; Gallinoro, E.; Monizzi, G.; Candreva, A.; Munhoz, D.; Vassilev, D.; et al. Prevalence of Coronary Microvascular Disease and Coronary Vasospasm in Patients with Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Caobelli, F.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, K.; Yu, F. The Role of Deep Learning in Myocardial Perfusion Imaging for Diagnosis and Prognosis: A Systematic Review. iScience 2024, 27, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, W.-Y.I.; Su, M.-Y.M.; Tseng, Y.-H.E. Introduction to Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: Technical Principles and Clinical Applications. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2016, 32, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.E.; Hong, Y.J.; Kim, H.-K.; Kim, J.A.; Na, J.O.; Yang, D.H.; Kim, Y.J.; Choi, E.-Y. 2014 Korean Guidelines for Appropriate Utilization of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Joint Report of the Korean Society of Cardiology and the Korean Society of Radiology. Korean J. Radiol. 2014, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, D.P.; De Pasquale, C.G.; Selvanayagam, J.B. Heart Failure with Normal Ejection Fraction: The Complementary Roles of Echocardiography and CMR Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 3, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.R.; Salerno, M.; Kwong, R.Y.; Singh, A.; Heydari, B.; Kramer, C.M. Stress Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Myocardial Perfusion Imaging. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1655–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen Johansson, R.; Tornvall, P.; Sörensson, P.; Nickander, J. Reduced Stress Perfusion in Myocardial Infarction with Nonobstructive Coronary Arteries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaert, D.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Giri, S.; Mihai, G.; Rajagopalan, S.; Simonetti, O.P.; Raman, S.V. Direct T2 Quantification of Myocardial Edema in Acute Ischemic Injury. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2011, 4, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajiah, P.; Desai, M.Y.; Kwon, D.; Flamm, S.D. MR Imaging of Myocardial Infarction. RadioGraphics 2013, 33, 1383–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.F.; A Thrysøe, S.; Robich, M.P.; Paaske, W.P.; Ringgaard, S.; Bøtker, H.E.; Hansen, E.S.S.; Kim, W.Y. Assessment of Intramyocardial Hemorrhage by T1-Weighted Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Reperfused Acute Myocardial Infarction. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2012, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugander, M.; Bagi, P.S.; Oki, A.J.; Chen, B.; Hsu, L.; Aletras, A.H.; Shah, S.; Greiser, A.; Kellman, P.; Arai, A.E. Myocardial Edema as Detected by Pre-Contrast T1 and T2 CMR Delineates Area at Risk Associated with Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messroghli, D.; Walters, K.; Plein, S.; Sparrow, P.; Friedrich, M.G.; Ridgway, J.P.; Sivananthan, M.U. Myocardial T1 Mapping: Application to Patients with Acute and Chronic Myocardial Infarction. Magn. Reson. Med. 2007, 58, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellman, P.; Wilson, J.R.; Xue, H.; Ugander, M.; Arai, A.E. Extracellular Volume Fraction Mapping in the Myocardium, Part 1: Evaluation of an Automated Method. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2012, 14, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, W.; Duffy, S.J.; White, D.A.; Gao, X.-M.; Du, X.-J.; Ellims, A.H.; Dart, A.M.; Taylor, A.J. Acute Left Ventricular Remodeling Following Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 5, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauner, K.U.; Biffar, A.; Theisen, D.; Greiser, A.; Zech, C.J.; Nguyen, E.T.; Reiser, M.F.; Wintersperger, B.J. Extracellular Volume Fractions in Chronic Myocardial Infarction. Investig. Radiol. 2012, 47, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.J.; Kim, H.W.; James, O.; Parker, M.; Wu, E.; Bonow, R.O.; Judd, R.M.; Kim, R.J. Prevalence of Regional Myocardial Thinning and Relationship with Myocardial Scarring in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA 2013, 309, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.R.; McCann, G.P. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance: Applications and Practical Considerations for the General Cardiologist. Heart 2019, 106, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiry, M.A.; Abdelaziz, I.; Davidson, R.; Mahmoud, M.Z. The Recent Advances, Drawbacks, and the Future Directions of CMRI in the Diagnosis of IHD. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotschy, A.; Niemann, M.; Kozerke, S.; Lüscher, T.F.; Manka, R. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance for the Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 193, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwitter, J.; Arai, A.E. Assessment of Cardiac Ischaemia and Viability: Role of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltzfus, M.T.; Capodarco, M.D.; Anamika, F.N.U.; Gupta, V.; Jain, R.; Stoltzfus, M.T.; Capodarco, M.D.; Anamika, F.N.U.; Gupta, V.; Jain, R. Cardiac MRI: An Overview of Physical Principles with Highlights of Clinical Applications and Technological Advancements. Cureus 2024, 16, e55519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Q.; Lelieveldt, B.P.F.; van der Geest, R.J. Deep Learning for Quantitative Cardiac MRI. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 214, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggiano, A.; Mushtaq, S.; Fusini, L.; Muratori, M.; Pontone, G.; Pepi, M. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Imaging: Current Applications and New Horizons. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2025, 35, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Farzaneh-Far, A.; Kim, R.J. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance in Patients with Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 55, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pu, J. Recent Advances in Cardiac Magnetic Resonance for Imaging of Acute Myocardial Infarction. Small Methods 2023, 8, e2301170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, E.; Greenwood, J.P.; McCann, G.P.; Bettencourt, N.; Shah, A.M.; Hussain, S.T.; Perera, D.; Plein, S.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Paul, M.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Perfusion or Fractional Flow Reserve in Coronary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2418–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.P.; Biederman, R.W.W. Cardiac MRI. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 99, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.-S.H.; Horwood, L.; Stojanovska, J.; Attili, A.; Frank, L.; Oral, H.; Bogun, F. Safety of CMR in Patients with Cardiac Implanted Electronic Devices. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2016, 18, O123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, N. Management of Patients with Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices Undergoing Magnetic Resonance Imaging—Proposal for Unified Hospital Protocol: Croatian Working Group on Arrhythmias and Cardiac Pacing. Acta Clin. Croat. 2020, 59, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, K.; Basso, C.; d’Amati, G.; Giordano, C.; Kholová, I.; Preston, S.D.; Rizzo, S.; Sabatasso, S.; Sheppard, M.N.; Vink, A.; et al. Diagnosis of Myocardial Infarction at Autopsy: AECVP Reappraisal in the Light of the Current Clinical Classification. Virchows Arch. 2019, 476, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.R.; Alkhouli, M. Past, Present, and Future of Interventional Cardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2738–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, G.; Byrne, R.; Windecker, S.; Kastrati, A. State of the Art: Coronary Artery Stents—Past, Present and Future. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scafa Udriște, A.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Bădilă, E. Cardiovascular Stents: A Review of Past, Current, and Emerging Devices. Materials 2021, 14, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twing, A.H.; Meyer, J.; Dickens, H.; Young, M.N.; Shroff, A. A Brief History of Intracoronary Imaging. Curr. Cardiovasc. Imaging Rep. 2020, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavarini, A.; Kilic, I.D.; Redondo Diéguez, A.; Longo, G.; Vandormael, I.; Pareek, N.; Kanyal, R.; De Silva, R.; Di Mario, C. Intracoronary Imaging. Heart 2017, 103, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, J.; Guedes, C.; Soares, P.; Zalc, S.; Campos, C.M.; Lopes, A.C.; Spadaro, A.G.; Perin, M.A.; Filho, A.E.; Takimura, C.K.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance to Minimize the Use of Iodine Contrast in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentias, A.; Sarrazin, M.V.; Saad, M.; Panaich, S.; Kapadia, S.; Horwitz, P.A.; Girotra, S. Long-Term Outcomes of Coronary Stenting with and without Use of Intravascular Ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.J.; Lim, S.; Choo, E.H.; Hwang, B.-H.; Kim, C.J.; Park, M.-W.; Lee, J.-M.; Park, C.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoo, K.-D.; et al. Impact of Intravascular Ultrasound on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. JACC. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 2431–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darmoch, F.; Alraies, M.C.; Al-Khadra, Y.; Moussa Pacha, H.; Pinto, D.S.; Osborn, E.A. Intravascular Ultrasound Imaging–Guided versus Coronary Angiography–Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e013678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintz, G.S.; Lefèvre, T.; Lassen, J.F.; Testa, L.; Pan, M.; Singh, J.; Stankovic, G.; Banning, A.P. Intravascular Ultrasound in the Evaluation and Treatment of Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: A Consensus Statement from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 2018, 14, e467–e474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Matsumura, M.; Usui, E.; Noguchi, M.; Fujimura, T.; Fall, K.N.; Zhang, Z.; Nazif, T.M.; Parikh, S.A.; Rabbani, L.E.; et al. Intravascular Ultrasound–Derived Calcium Score to Predict Stent Expansion in Severely Calcified Lesions. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.F.; Patel, M.P.; Abbott, J.D.; Bangalore, S.; Brilakis, E.S.; Croce, K.J.; Doshi, D.; Kaul, P.; Kearney, K.E.; Kerrigan, J.L.; et al. SCAI Expert Consensus Statement on the Management of Calcified Coronary Lesions. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2024, 3, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugo, F.; Franzino, M.; Massaro, G.; Maltese, L.; Cavallino, C.; Abdirashid, M.; Benedetto, D.; Costa, F.; Rametta, F.; Sangiorgi, G.M. The Role of IVUS in Coronary Complications. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. Off. J. Soc. Card. Angiogr. Interv. 2025, 105, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesic, M.; Mladenovic, D.; Vukcevic, V.; Jelic, D.; Milasinovic, D. The Role of Intravascular Ultrasound in the Evaluation and Treatment of Free-Floating Stent Struts Following Inadequate Ostial Circumflex Stenting: A Case Report. Medicina 2024, 60, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, N.C.; Johnson, T.W. Intracoronary Optical Coherence Tomography—An Introduction. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 100, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, H.G.; Costa, M.A.; Guagliumi, G.; Rollins, A.M.; Simon, D.I. Intracoronary Optical Coherence Tomography: A Comprehensive Review. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009, 2, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahandeh, N.; Kashiyama, K.; Honda, Y.; Nsair, A.; Ali, Z.A.; Tobis, J.M.; Fearon, W.F.; Parikh, R.V. Invasive Coronary Imaging Assessment for Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy: State-of-The-Art Review. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2022, 1, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velleca, A.; Shullo, M.A.; Dhital, K.; Azeka, E.; Colvin, M.; DePasquale, E.; Farrero, M.; García-Guereta, L.; Jamero, G.; Khush, K.; et al. The International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Guidelines for the Care of Heart Transplant Recipients. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, e1–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A.; Karimi Galougahi, K.; Mintz, G.S.; Maehara, A.; Shlofmitz, R.A.; Mattesini, A. Intracoronary Optical Coherence Tomography: State of the Art and Future Directions. EuroIntervention 2021, 17, e105–e123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigkas, G.; Spyropoulou, P.; Bousoula, E.; Apostolos, A.; Vasilagkos, G.; Karamasis, G.; Dimitriadis, K.; Moulias, A.; Davlouros, P. Intracoronary Imaging: Current Practice and Future Perspectives. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlofmitz, E.; Croce, K.; Bezerra, H.; Sheth, T.; Chehab, B.; Nick; Shlofmitz, R.; Ali, Z.A. The MLD MAX OCT Algorithm: An Imaging-Based Workflow for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2022, 100, S7–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, F.; Kumar, S.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Tu, S. Intravascular Imaging for Acute Coronary Syndrome. npj Cardiovasc. Health 2025, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Park, S.-J.; Jang, Y.; Lee, S.; Kim, C.-J.; Minami, Y.; Ong, D.; Soeda, T.; Vergallo, R.; Lee, H.; et al. Comparison of Neoatherosclerosis and Neovascularization between Patients with and without Diabetes. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.A.; Rathod, K.S.; Koganti, S.; Hamshere, S.; Astroulakis, Z.; Lim, P.; Sirker, A.; O’Mahony, C.; Jain, A.K.; Knight, C.J.; et al. Angiography Alone versus Angiography plus Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2018, 11, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-J.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Cho, D.-K.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, S.M.; Hur, S.-H.; Heo, J.H.; Jang, J.-Y.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography-Guided versus Angiography-Guided Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with Complex Lesions (OCCUPI): An Investigator-Initiated, Multicentre, Randomised, Open-Label, Superiority Trial in South Korea. Lancet 2024, 404, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, N.R.; Andreasen, L.D.; Neghabat, O.; Laanmets, P.; Kumsars, I.; Bennett, J.; Olsen, N.T.; Odenstedt, J.; Hoffmann, P.; Dens, J.; et al. OCT or Angiography Guidance for PCI in Complex Bifurcation Lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufaro, V.; Jaffer, F.A.; Serruys, P.W.; Onuma, Y.; van Stone, G.W.; Muller, J.E.; Marcu, L.; Van Soest, G.; Courtney, B.K.; Tearney, G.J.; et al. Emerging Hybrid Intracoronary Imaging Technologies and Their Applications in Clinical Practice and Research. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2024, 17, 1963–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohyeldin, M.; Mohamed, F.O.; Allu, S.; Shrivastava, S.F. Mason Sones Jr.: The Serendipitous Discovery of Coronary Angiography and Its Lasting Impact on Cardiology. Cureus 2024, 16, e61080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milzi, A.; Dettori, R.; Lubberich, R.K.; Reith, S.; Frick, M.; Burgmaier, K.; Marx, N.; Burgmaier, M. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Is a Hallmark of All Subtypes of MINOCA. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 113, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Travieso, A.; van der Hoeven, N.; Lombardi, M.; van Leeuwen, M.A.; Janssens, G.; Shabbir, A.; Mejía-Rentería, H.; Milasinovic, D.; Gonzalo, N.; et al. Angiography-versus Wire-Based Microvascular Resistance Index to Detect Coronary Microvascular Obstruction Associated with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 411, 132256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaramella, L.; Di Serafino, L.; Mitrano, L.; De Rosa, M.L.; Carbone, C.; Rea, F.S.; Monaco, S.; Scalamogna, M.; Cirillo, P.; Esposito, G. Invasive Assessment of Coronary Microcirculation: A State-of-The-Art Review. Diagnostics 2023, 14, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, B. His Master’s Art, Andreas Grüntzig’s Approach to Performing and Teaching Coronary Angioplasty. EuroIntervention 2017, 13, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI Guideline for the Management of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2025, 151, e771–e862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.C.; Stewart, C.; Weir, N.W.; Newby, D.E. Using Radiation Safely in Cardiology: What Imagers Need to Know. Heart 2019, 105, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedetti, G.; Pizzi, C.; Gavaruzzi, G.; Lugaresi, F.; Cicognani, A.; Picano, E. Suboptimal Awareness of Radiologic Dose among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Stress Scintigraphy. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2008, 5, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D. Dealing with At-Risk Populations in Radiological/Nuclear Emergencies. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2009, 134, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Walli-Attaei, M.; Gray, A.; Torbica, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Huculeci, R.; Bairami, F.; Aboyans, V.; Timmis, A.D.; Vardas, P.; et al. Economic Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases in the European Union: A Population-Based Cost Study. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4752–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschetti, K.; Kwong, R.Y.; Petersen, S.E.; Lombardi, M.; Garot, J.; Atar, D.; Rademakers, F.; Sierra-Galan, L.M.; Mavrogeni, S.; Li, K.; et al. Cost-Minimization Analysis for Cardiac Revascularization in 12 Health Care Systems Based on the EuroCMR/SPINS Registries. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Pandya, A.; Steel, K.; Bingham, S.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Mikolich, J.R.; Arai, A.E.; Bandettini, W.P.; Patel, A.R.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Stress Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Stable Chest Pain Syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezel, T.; Toupin, S.; Bousson, V.; Hamzi, K.; Hovasse, T.; Lefevre, T.; Chevalier, B.; Unterseeh, T.; Sanguineti, F.; Champagne, S.; et al. A Machine Learning Model Using Cardiac CT and MRI Data Predicts Cardiovascular Events in Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. Radiology 2025, 314, e233030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Li, H.; Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.; Guo, K. New Technique for Enhancing Residual Oil Recovery from Low-Permeability Reservoirs: The Cooperation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria and SiO2 Nanoparticles. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.K.; Sejr-Hansen, M.; Maillard, L.; Campo, G.; Råmunddal, T.; E Stähli, B.; Guiducci, V.; Di Serafino, L.; Escaned, J.; Santos, I.A.; et al. Quantitative Flow Ratio versus Fractional Flow Reserve for Coronary Revascularisation Guidance (FAVOR III Europe): A Multicentre, Randomised, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2024, 404, 1835–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, T.K.; Hothi, S.S.; Venugopal, V.; Taleyratne, J.; O’bRien, D.; Adnan, K.; Sehmi, J.; Daskalopoulos, G.; Deshpande, A.; Elfawal, S.; et al. The Use and Efficacy of FFR-CT. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 1056–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopoulos, A.A.; Gaemperli, O. Hybrid Imaging in Ischemic Heart Disease. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.; Han, D.; Danad, I.; Hartaigh, B.Ó.; Lee, J.H.; Gransar, H.; Stuijfzand, W.J.; Roudsari, H.M.; Park, M.W.; Szymonifka, J.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Hybrid Cardiac Imaging Methods for Assessment of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Compared with Stand-Alone Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Different Diagnostic Method | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | Regional wall motion abnormalities, CFR- perfusion reserve, LVEF, noninvasive | Suboptimal windows, suboptimal exertion, tachyarrhythmia, poor sensitivity in balanced ischemia, operator dependent |

| CCTA | Quantification of atherosclerosis, verification of coronary anatomy and bypass grafts | Radiation exposure, contrast nephropathy, allergies, heavy calcifications, heart rate dependent |

| CMR | Tissue characterization- LGE scar detection, perfusion defects, good spatial and temporal resolution, regional wall motion abnormalities, no radiation exposure, noninvasive | Time consuming, noncompatible metal devices, claustrophobia, breath holding method, heart rate dependent |

| SPECT and PET | Perfusion defects, myocardial viability | Radiation exposure, attenuation artefacts |

| ICA | Direct lesion visualization, PCI if indicated, further functional and morphological assessment | Radiation exposure, invasive, possible serious complications |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marija, B.; Lidija, M.; Marko, R.; Milorad, T.; Snezana, T.; Marija, B.; Popovic, D. From Echo to Coronary Angiography: Optimizing Ischemia Evaluation Through Multimodal Imaging. Medicina 2025, 61, 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122212

Marija B, Lidija M, Marko R, Milorad T, Snezana T, Marija B, Popovic D. From Echo to Coronary Angiography: Optimizing Ischemia Evaluation Through Multimodal Imaging. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122212

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarija, Babic, Mikic Lidija, Ristic Marko, Tesic Milorad, Tadic Snezana, Bjelobrk Marija, and Dejana Popovic. 2025. "From Echo to Coronary Angiography: Optimizing Ischemia Evaluation Through Multimodal Imaging" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122212

APA StyleMarija, B., Lidija, M., Marko, R., Milorad, T., Snezana, T., Marija, B., & Popovic, D. (2025). From Echo to Coronary Angiography: Optimizing Ischemia Evaluation Through Multimodal Imaging. Medicina, 61(12), 2212. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122212