A Comparison of Periodontal Health in Elderly Individuals with and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

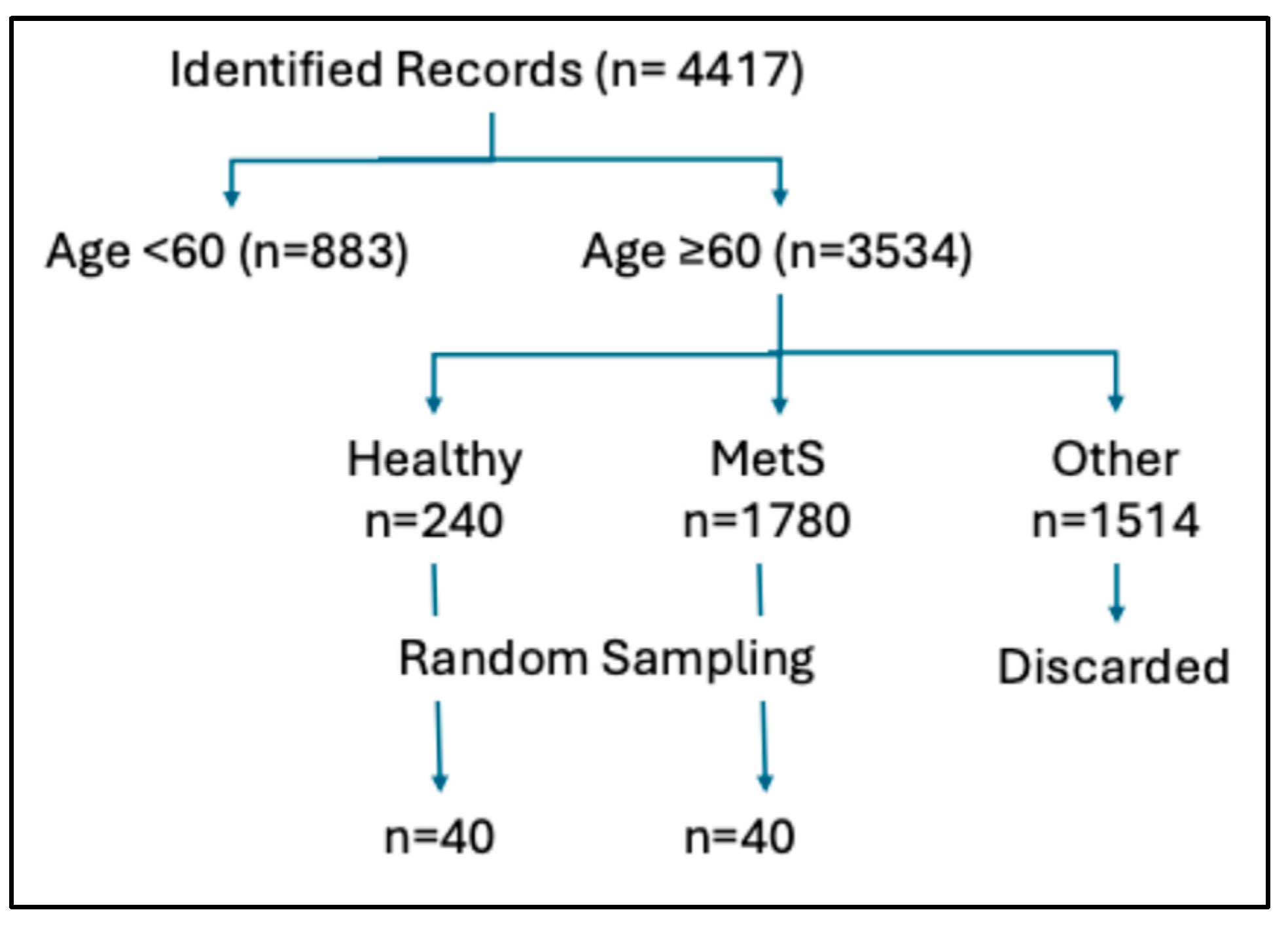

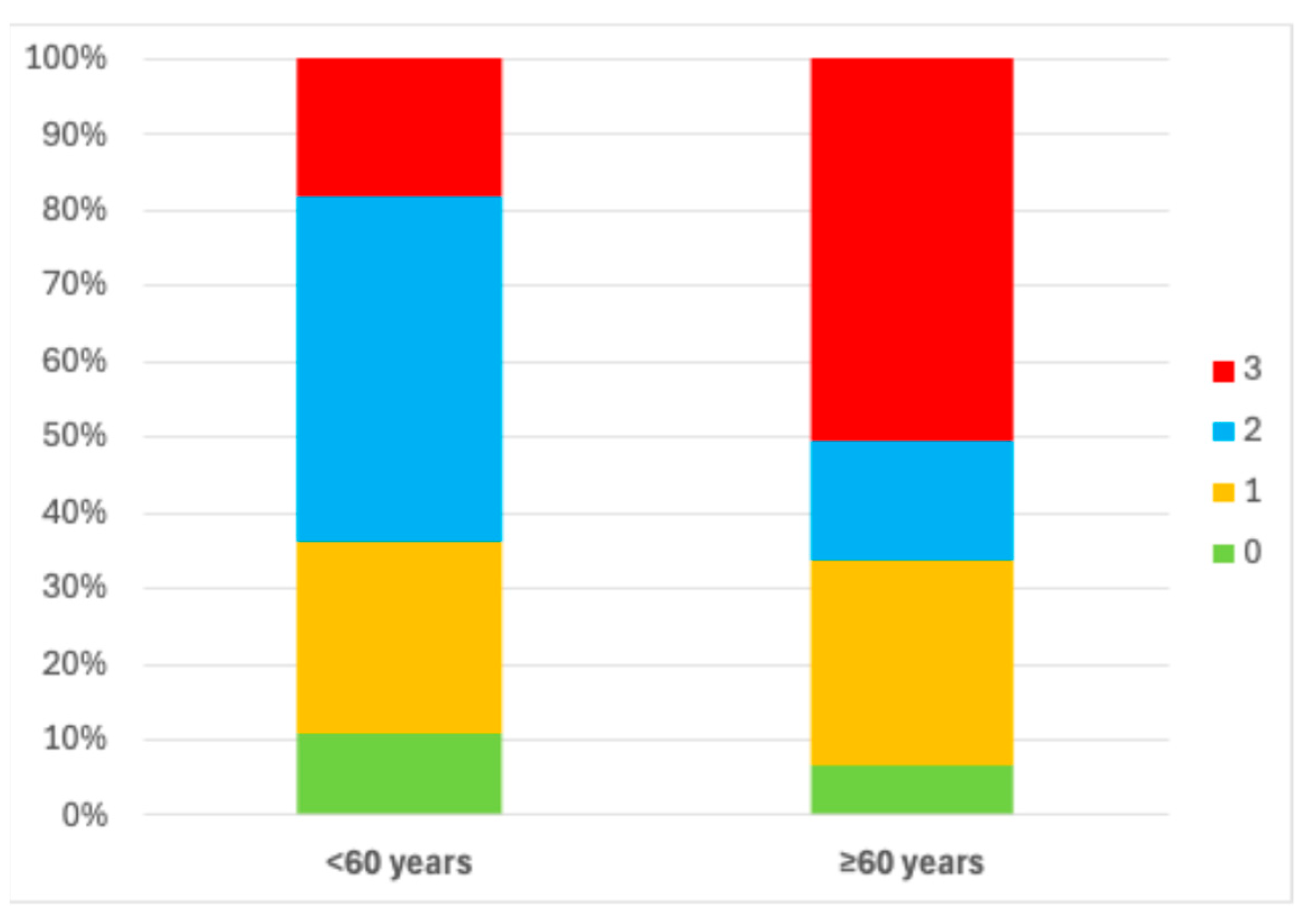

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MetS | Metabolic Syndrome |

References

- Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S173–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G. Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: Keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 2014, 35, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekici, A.; Kantarci, A.; Hasturk, H.; Van Dyke, T.E. Inflammatory and immune pathways in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000 2014, 64, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eke, P.I.; Dye, B.A.; Wei, L.; Thornton-Evans, G.O.; Genco, R.J. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, P.I.; Wei, L.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Thornton-Evans, G.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; McGuire, L.C.; Genco, R.J. Periodontitis prevalence in adults ≥ 65 years of age, in the USA. Periodontology 2000 2016, 72, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Brewer, H.B., Jr.; Cleeman, J.I.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Lenfant, C.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Definition of metabolic syndrome: Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, e13–e18. [Google Scholar]

- Kosho, M.X.F.; Verhelst, A.R.E.; Teeuw, W.J.; van Bruchem, S.; Nazmi, K.; Gerdes, V.E.A.; Loos, B.G. The Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome and Undiagnosed Diabetes in Periodontitis Patients and Non-Periodontitis Controls in a Dental School. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Huang, Y. Metabolic syndrome exacerbates inflammation and bone loss in periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.; Hoffmann, T.; Fischer, S.; Bornstein, S.; Grassler, J.; Noack, B. Obesity alters composition and diversity of the oral microbiota in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus independently of glycemic control. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, S.; Suvan, J.; Deschner, J. The association of periodontal diseases with metabolic syndrome and obesity. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, J.; Koponen, K.; Kambur, O.; Manzoor, M.; Aarnisalo, K.; Nissilä, V.; Männistö, S.; Salomaa, V.; Jousilahti, P.; Könönen, E.; et al. The Association of Periodontitis with Risk of Prevalent and Incident Metabolic Syndrome. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2025, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wu, H.; Fu, Z.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q. The Association Between Periodontitis and the Prevalence and Prognosis of Metabolic Syndrome. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2025, 18, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Shimazaki, Y.; Yoshii, S.; Takeyama, H. Periodontitis and the incidence of metabolic syndrome: An 8-year longitudinal study of an adult Japanese cohort. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.X.; Chaudhary, N.; Akinyemiju, T. Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence by Race/Ethnicity and Sex in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2017, 14, E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau USC. Older Americans Month: May 2017. 2017. Available online: www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2017/cb17-ff08.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Swami, V.; Stieger, S.; Harris, A.S.; Nader, I.W.; Pietschnig, J.; Voracek, M.; Tovée, M.J. Further investigation of the validity and reliability of the photographic figure rating scale for body image assessment. J. Pers. Assess. 2012, 94, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conover, W.J.; Iman, L. Rank Transformations as a Bridge Between Parametric and Nonparametric Statistics. Am. Stat. 1981, 35, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassi, E.; Pervanidou, P.; Kaltsas, G.; Chrousos, G. Metabolic syndrome: Definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.K.; Jensen, M.D. Metabolic changes in aging humans: Current evidence and therapeutic strategies. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e158451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. Aging of the Immune System. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, S422–S428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, M.J.; Reynolds, M.A.; Shiau, H.; Choe, K.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L. Association of periodontitis and metabolic syndrome in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 22, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaye, E.K.; Chen, N.; Cabral, H.J.; Vokonas, P.; Garcia, R.I. Metabolic Syndrome and Periodontal Disease Progression in Men. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. The association between periodontal disease severity and metabolic syndrome in Vietnamese patients. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegelberg, P.; Tervonen, T.; Knuuttila, M.; Jokelainen, J.; Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, S.; Auvinen, J.; Ylöstalo, P. Long-term metabolic syndrome is associated with periodontal pockets and alveolar bone loss. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2019, 46, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlushchenko, T.A.; Batig, V.M.; Borysenko, A.V.; Tokar, O.M.; Batih, I.V.; Vynogradova, O.M.; Boychuk-Tovsta, O.G. Prevalence and Intensity of Periodontal Disease in Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome. J. Med. Life 2020, 13, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, U.J.; Choi, M.S. Obesity and its metabolic complications: The role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 6184–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, M.; Zatterale, F.; Naderi, J.; Parrillo, L.; Formisano, P.; Raciti, G.A.; Beguinot, F.; Miele, C. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboleda, S.; Vargas, M.; Losada, S.; Pinto, A. Review of obesity and periodontitis: An epidemiological view. Br. Dent. J. 2019, 227, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, Z.; Safii, S.H.; Vaithilingam, R.D.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Javed, F.; Vohra, F. Efficacy of non-surgical periodontal therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis among obese and non-obese patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pischon, N.; Heng, N.; Bernimoulin, J.P.; Kleber, B.M.; Willich, S.N.; Pischon, T. Obesity, inflammation, and periodontal disease. J. Dent. Res. 2007, 86, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozcan, E.; Saygun, N.I.; Serdar, M.A.; Kubar, A.; Bengi, V.U. Porphyromonas gingivalis and Epstein-Barr Virus Are Associated With Increased Levels of Visfatin in Gingival Crevicular Fluid. J. Periodontol. 2016, 87, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khocht, A.; Paster, B.; Lenoir, L.; Irani, C.; Fraser, G. Metabolomic profiles of obesity and subgingival microbiome in periodontally healthy individuals: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2023, 50, 1455–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Z.; Yuan, Y.H.; Liu, H.H.; Li, S.S.; Zhang, B.W.; Chen, W.; An, Z.-J.; Chen, S.-Y.; Wu, Y.-Z.; Han, B.; et al. Epidemiologic relationship between periodontitis and type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumaedi, A.I.; Purnamasari, D.; Wijaya, I.P.; Soeroso, Y. The relationship of diabetes, periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2019, 13, 1675–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Al-Askar, M.; Al-Hezaimi, K. Cytokine profile in the gingival crevicular fluid of periodontitis patients with and without type 2 diabetes: A literature review. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.J.; Preshaw, P.M.; Lalla, E. A review of the evidence for pathogenic mechanisms that may link periodontitis and diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, S113–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, C.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll Cardiol. 2018, 71, e127–e248. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesi, C.; Dentali, F.; Nicolini, E.; Maresca, A.M.; Tayebjee, M.H.; Franz, M.; Tayebjee, M.H.; Franz, M.; Guasti, L.; Venco, A.; et al. Plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hypertens. 2012, 30, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virdis, A.; Dell’Agnello, U.; Taddei, S. Impact of inflammation on vascular disease in hypertension. Maturitas 2014, 78, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, X.F.; Ng, C.Y.; Badiah, B.; Das, S. Association between hypertension and periodontitis: Possible mechanisms. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 768237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsioufis, C.; Kasiakogias, A.; Thomopoulos, C.; Stefanadis, C. Periodontitis and blood pressure: The concept of dental hypertension. Atherosclerosis 2011, 219, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, M.F.; Brilhante, F.V.; Goncalves, T.E.; Pires, A.G.; Napimoga, M.H.; Marques, M.R.; Duarte, P.M. Hypertension may affect tooth-supporting alveolar bone quality: A study in rats. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khocht, A.; Rogers, T.; Janal, M.N.; Brown, M. Gingival Fluid Inflammatory Biomarkers and Hypertension in African Americans. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2017, 2, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MetS Group n = 32 | Healthy Group n = 33 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Ave. (SD) years | 78.12 (7.43) | 73.18 (8.48) | 0.01 |

| Gender (male %) | 53 | 45 | 0.53 |

| Race | 0.15 | ||

| Asian % | 15.63 | 12.12 | |

| Black % | 9.38 | 0 | |

| Hispanic % | 9.38 | 6.06 | |

| White % | 65.63 | 81.82 | |

| BMI | 34 (32–35) | 26 (24–27.5) | <0.0001 |

| Waist circumference | 42 (39–44) | 31 (30–33) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes % | 100 | 0 | |

| Hypertension % | 100 | 0 | |

| Current smoker | 6.25 | 3.03 | 0.53 |

| MetS Group n = 32 | Healthy Group n = 33 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI% | 45.5 (23–66.25) | 42 (23–65.5) | 0.89 |

| PD% (≥4 mm) | 7.17 (1.86–18.76) | 1.11 (0–4.64) | 0.001 |

| BOP% | 21.5 (5–35.25) | 4 (2–16.25) | 0.0005 |

| ABL average (mm) | 3.24 (2.52–4.07) | 2.53 (2.03–3.54) | 0.03 |

| ABL % ≥ 4 mm | 26.38 (12.21–49.45) | 12.24 (0–34.09) | 0.02 |

| Missing teeth (number) | 5.5 (3–7) | 5 (1–8.5) | 0.55 |

| Model 1 Demographics | Model 2 Cigarette Smoking | Model 3 Plaque Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PD % ≥ 4 mm | 0.31 * | 0.39 ** | 0.40 ** |

| BOP% | 0.41 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.42 ** |

| ABL average (mm) | 0.29 * | 0.24 * | 0.28 * |

| ABL % ≥ 4 mm | 0.31 * | 0.26 * | 0.29 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LeNoir, J.; Lenoir, L.; Khocht, A. A Comparison of Periodontal Health in Elderly Individuals with and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122200

LeNoir J, Lenoir L, Khocht A. A Comparison of Periodontal Health in Elderly Individuals with and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122200

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeNoir, Jacqueline, Leticia Lenoir, and Ahmed Khocht. 2025. "A Comparison of Periodontal Health in Elderly Individuals with and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Study" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122200

APA StyleLeNoir, J., Lenoir, L., & Khocht, A. (2025). A Comparison of Periodontal Health in Elderly Individuals with and Without Metabolic Syndrome: A Retrospective Study. Medicina, 61(12), 2200. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122200