Effectiveness of a Fluid-Collection Device for the Duodenoscope Biopsy Channel During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Data Collection

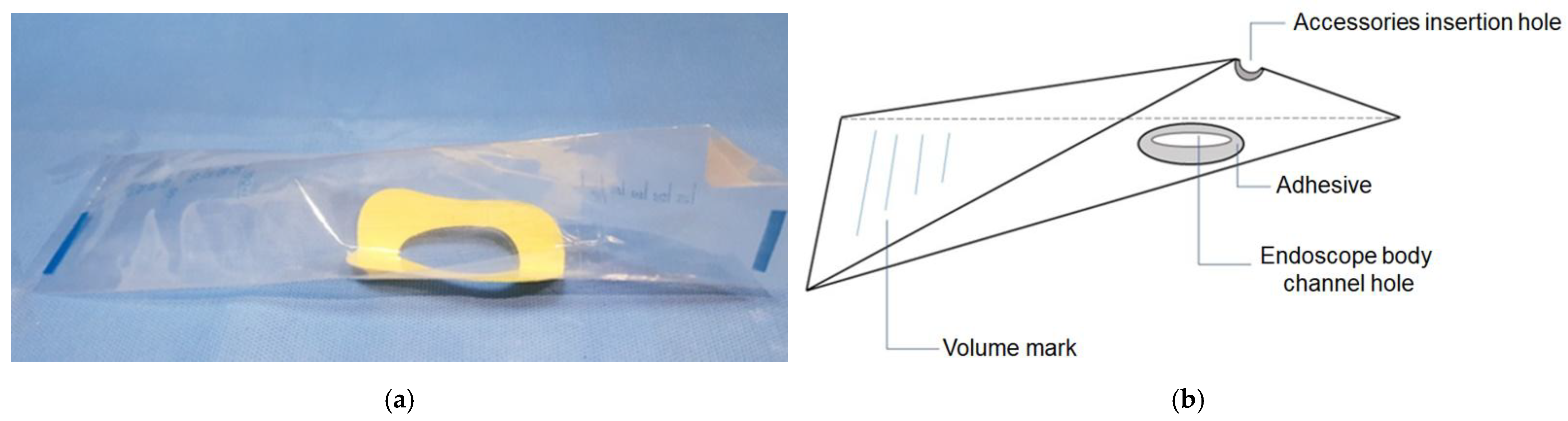

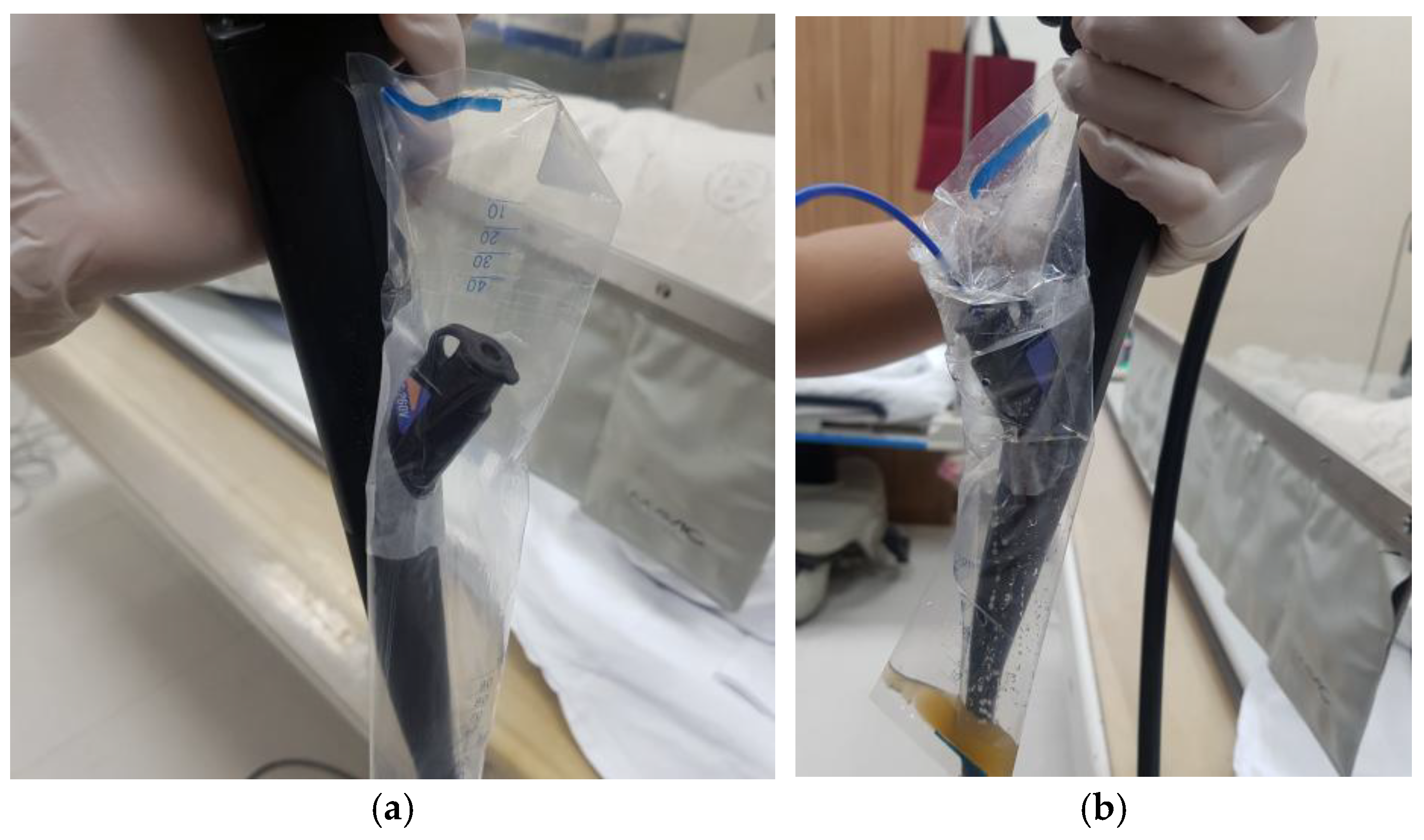

2.2. Device and Technique

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison Between Low-Leakage and High-Leakage Groups

3.2. Association Between Procedural Complexity (Schutz Grade) and Fluid Leakage

3.3. Association Between Procedural Factors and Fluid Leakage Volume

3.4. Predictive Factors for Significant Fluid Leakage in ERCP: Results from Logistic Regression Analysis

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis Using an Alternative Cutoff

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| ERCP | endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

References

- Adler, D.G.; Baron, T.H.; Davila, R.E.; Egan, J.; Hirota, W.K.; Leighton, J.A.; Qureshi, W.; Rajan, E.; Zuckerman, M.J.; Fanelli, R.; et al. ASGE guideline: The role of ERCP in diseases of the biliary tract and the pancreas. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 62, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Standards of Practice Committee; Anderson, M.A.; Appalaneni, V.; Ben-Menachem, T.; Decker, G.A.; Early, D.S.; Evans, J.A.; Fanelli, R.D.; Fisher, D.A.; Fisher, L.R.; et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and treatment of patients with biliary neoplasia. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 77, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.C.; Santo, P.A.D.E.; Baraldo, S.; Nau, A.L.; Meine, G.C. EUS-versus ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 395–405.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Chandrasekhara, V.; Chathadi, K.V.; Acosta, R.D.; Decker, G.A.; Early, D.S.; Eloubeidi, M.A.; Evans, J.A.; Faulx, A.L.; Fanelli, R.D.; et al. The role of endoscopy in benign pancreatic disease. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015, 82, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Li, T.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, B.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided vs. ERCP-guided biliary drainage for malignant biliary obstruction: A up-to-date meta-analysis and systematic review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 1247–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröner, P.T.; Bilal, M.; Samuel, R.; Umar, S.; Abougergi, M.S.; Lukens, F.J.; Raimondo, M.; Carr-Locke, D.L. Use of ERCP in the United States over the past decade. Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 8, E761–E769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, N.; Elmunzer, B.J.; Allain, T.; Parkins, M.D.; Sheth, P.M.; Waddell, B.J.; Du, K.; Douchant, K.; Oladipo, O.; Saleem, A.; et al. Effect of disposable elevator cap duodenoscopes on persistent microbial contamination and technical performance of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: The ICECAP randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, R.M.; McDonnell, G. Superbugs on duodenoscopes: The challenge of cleaning and disinfection of reusable devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 3118–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.; Alfa, M.J. Cleaning and disinfecting gastrointestinal endoscopy equipment. In Clinical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 32–50.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. “Meticulous” cleaning of duodenoscopes may not eliminate infection risk, US watchdog warns. Br. Med. J. 2015, 350, h997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, Z.; Huang, S.; Ren, J.; Luo, M.; Xu, X.; Chen, G.; et al. Practical experience of endoscope reprocessing and working-platform disinfection in COVID-19 patients: A report from Guangdong, China during the pandemic. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2020, 9869742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, S.M.; Yin, T.; Xiong, J.X.; Peng, T.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.S. Treatment of pancreatic diseases and prevention of infection during outbreak of 2019 coronavirus disease. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 2020, 58, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutfless, S. Endoscope infection transmission state-of-the-art: Beyond duodenoscopes to a culture of infection prevention. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 36, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, M.; Liao, G.-Q.; Zhao, Y.-E.; Yue, D.-Y.; Yuan, Y.; Cheng, B.; Qin, H. Precautionary measures: Performing ERCP on a patient with juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula (JPDD)-related biliary stone after COVID-19 lockdown restriction lifted in Wuhan, China. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schutz, S.M. Grading the degree of difficulty of ERCP procedures. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 7, 674–676. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Xu, T.; Ngamruengphong, S.; A Makary, M.; Kalloo, A.; Hutfless, S. Rates of infection after colonoscopy and osophagogastroduodenoscopy in ambulatory surgery centres in the USA. Gut 2018, 67, 1626–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstead, C.L.; Buro, B.L.; Hopkins, K.M.; Eiland, J.E.; Wetzler, H.P.; Lichtenstein, D.R. Duodenoscope-associated infection prevention: A call for evidence-based decision making. Endosc. Int. Open 2020, 8, E1769–E1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakman, J.A.; Erler, N.S.; Vos, M.C.; Bruno, M.J. Risk evaluation of duodenoscope-associated infections in the Netherlands calls for a heightened awareness of device-related infections: A systematic review. Endoscopy 2022, 54, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günșahin, D.; Șandru, V.; Constantinescu, G.; Ilie, M.; Cabel, T.; Popescu, R.Ș.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Miron, V.D.; Balan, G.G.; Cotigă, D.; et al. A comprehensive review of digestive endoscopy-associated infections: Bacterial pathogens, host susceptibility, and the impact of viral hepatitis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhurwal, A.; Pioppo, L.; Reja, M.; Tawadros, A.; Sarkar, A.; Shahid, H.M.; Tyberg, A.; Kahaleh, M. Su1444 post ERCP bacteremia and post ERCP fever leads to early unplanned readmission—Incidence and outcomes. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, AB349–AB350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuduva Rajan, S.; Madireddy, S.; Jaladi, P.R.; Ravat, V.; Masroor, A.; Queeneth, U.; Rashid, W.; Patel, R.S. Burdens of postoperative infection in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography inpatients. Cureus 2019, 11, e5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Suo, J.; Liu, B.; Xing, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y. Post-ERCP infection and its epidemiological and clinical characteristics in a large Chinese tertiary hospital: A 4-year surveillance study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, P.B.; Connor, P.; Rawls, E.; Romagnuolo, J. Infection after ERCP, and antibiotic prophylaxis: A sequential quality-improvement approach over 11 years. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 67, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, G.G.; Sfarti, C.V.; Chiriac, S.A.; Stanciu, C.; Trifan, A. Duodenoscope-associated infections: A review. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.R.; Perisetti, A.; Coman, R.; Bansal, P.; Chhabra, R.; Goyal, H. Duodenoscope-associated infections: Update on an emerging problem. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2019, 64, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 183) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 69.3 ± 13.1 |

| Male, n (%) | 107 (58.5) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Biliary stone disease | 108 (59) |

| IgG4-related cholangitis | 3 (1.6) |

| Benign stricture | 22 (12) |

| Benign tumor | 2 (1.1) |

| Bile duct or gallbladder cancer | 20 (10.9) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 10 (5.5) |

| Bile leak | 8 (4.4) |

| Others | 10 (5.5) |

| Procedure time, min (mean ± SD) | 16.1 ± 12.6 |

| Duodenal irrigation frequency, times (mean ± SD) | 5.9 ± 2.4 |

| Volume of leaked fluid, mL (mean ± SD) | 11.3 ± 15.5 |

| ERCP status | First 81 (44.3%), Repeat 102 (55.7%) |

| Endoscopic procedure, n (%) | |

| Guidewire-assisted | 127 (69.4) |

| Stone extraction basket | 173 (94.5) |

| Retrieval balloon catheter | 153 (83.6) |

| Biopsy forceps | 22 (12) |

| Biliary metal stenting | 9 (4.9) |

| Biliary plastic stenting | 99 (54.1) |

| Biliary stent removal | 81 (44.3) |

| Variable | Low-Leakage Group (n = 126) | High-Leakage Group (n = 57) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 69.3 ± 13.5 | 69.5 ± 12.5 | 0.93 |

| Male, n (%) | 71 (56.3) | 36 (63.2) | 0.48 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.002 | ||

| Biliary stone disease | 86 (68) | 22 (39) | |

| IgG4-related cholangitis | 3 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Benign stricture | 13 (10) | 9 (16) | |

| Benign tumor | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Bile duct or gallbladder cancer | 6 (4.8) | 14 (25) | |

| Pancreatic cancer | 5 (4.0) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Bile leak | 7 (5.6) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Others | 5 (4.0) | 5 (8.8) | |

| Procedure time, min (mean ± SD) | 11.1 ± 8.1 | 27.2 ± 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Duodenal flushing, times (mean ± SD) | 5.0 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Volume of leaked fluid, mL (mean ± SD) | 2.5 ± 4.3 | ± 13.7 | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic procedure, n (%) | |||

| Guidewire-assisted procedure | 72 (57.2) | 55 (96.5) | <0.001 |

| Stone extraction basket | 125 (99.2) | 48 (84.2) | <0.001 |

| Retrieval balloon catheter | 108 (85.7) | 45 (78.9) | 0.35 |

| Biopsy forceps | 8 (6.3) | 14 (24.6) | 0.001 |

| Biliary metal stenting | 7 (5.6) | 2 (3.5) | 0.82 |

| Biliary plastic stenting | 49 (38.9) | 50 (87.7) | <0.001 |

| Biliary stent removal | 66 (52.4) | 15 (26.3) | 0.002 |

| Schutz Grade | n | Mean Leak (mL) | SD | Median Leak (mL) | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 59 | 5.1 | 10.8 | 0 | 0–5 |

| Grade 2 | 82 | 7.8 | 11.7 | 0 | 0–10 |

| Grade 3 | 34 | 27.9 | 18.7 | 20 | 11.2–40 |

| Grade 4 | 8 | 21.2 | 9.9 | 20 | 17.5–22.5 |

| Procedure | Category | n | Leaked Fluid (mL) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biliary metal stenting | No | 174 | 11.5 ± 15.7 | 0.15 |

| Yes | 9 | 6.7 ± 8.7 | ||

| Biliary plastic stenting | No | 84 | 3.4 ± 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 99 | 17.9 ± 16.9 | ||

| Biliary stent removal | No | 102 | 15.5 ± 17.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 81 | 5.9 ± 11.1 | ||

| Biopsy forceps | No | 161 | 9.1 ± 12.9 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 22 | 27.3 ± 22.3 | ||

| Guidewire-assisted procedure | No | 56 | 1.8 ± 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 127 | 15.4 ± 16.2 | ||

| 3 times | 1 | 30 ± NA | ||

| 2 times | 33 | 27.7 ± 16.8 | ||

| 1 time | 93 | 10.9 ± 13.6 | ||

| 0 times | 56 | 1.8 ± 7.4 | ||

| Retrieval balloon catheter | No | 30 | 13.3 ± 17.5 | 0.47 |

| Yes | 153 | 10.8 ± 15.1 | ||

| Stone extraction basket | No | 10 | 26.5 ± 12.5 | 0.003 |

| Yes | 173 | 10.4 ± 15.2 |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Male | 1.33 (0.70–2.53) | 0.39 | 0.42 (0.16–1.05) | 0.070 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.93 | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.318 |

| Malignancy | 4.65 (2.20–9.79) | <0.001 | 3.02 (1.13–8.39) | 0.029 |

| Procedure time (min) | 1.14 (1.10–1.19) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.06–1.17) | <0.001 |

| Duodenal flushing (≥6 times) | 20.07 (7.47–53.96) | <0.001 | 5.38 (1.80–18.75) | 0.004 |

| Guidewire use (≥1 time) | 20.63 (4.82–88.31) | <0.001 | ||

| Guidewire use (≥2 times) | 13.28 (5.48–32.16) | <0.001 | ||

| Stone extraction basket use | 0.04 (0.01–0.35) | 0.003 | ||

| Retrieval balloon catheter use | 0.63 (0.28–1.40) | 0.26 | ||

| Biopsy forceps use | 4.80 (1.88–12.25) | 0.001 | ||

| Biliary plastic stenting | 11.22 (4.71–26.75) | <0.001 | 4.53 (1.54–14.69) | 0.008 |

| Biliary metal stenting | 0.62 (0.12–3.07) | 0.56 | ||

| Biliary stent removal | 0.33 (0.16–0.64) | 0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.M.; Jung, I.; Sung, C.; Hong, S.; Kim, T.I.; Jeon, H.J.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, E.S.; Keum, B.; et al. Effectiveness of a Fluid-Collection Device for the Duodenoscope Biopsy Channel During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Medicina 2025, 61, 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122203

Lee HS, Lee JM, Jung I, Sung C, Hong S, Kim TI, Jeon HJ, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, et al. Effectiveness of a Fluid-Collection Device for the Duodenoscope Biopsy Channel During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122203

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Ho Seung, Jae Min Lee, Inhwan Jung, Chaeyun Sung, Seokju Hong, Tae In Kim, Han Jo Jeon, Hyuk Soon Choi, Eun Sun Kim, Bora Keum, and et al. 2025. "Effectiveness of a Fluid-Collection Device for the Duodenoscope Biopsy Channel During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122203

APA StyleLee, H. S., Lee, J. M., Jung, I., Sung, C., Hong, S., Kim, T. I., Jeon, H. J., Choi, H. S., Kim, E. S., Keum, B., Jeen, Y. T., & Lee, H. S. (2025). Effectiveness of a Fluid-Collection Device for the Duodenoscope Biopsy Channel During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Medicina, 61(12), 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122203