Use of Laser in Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

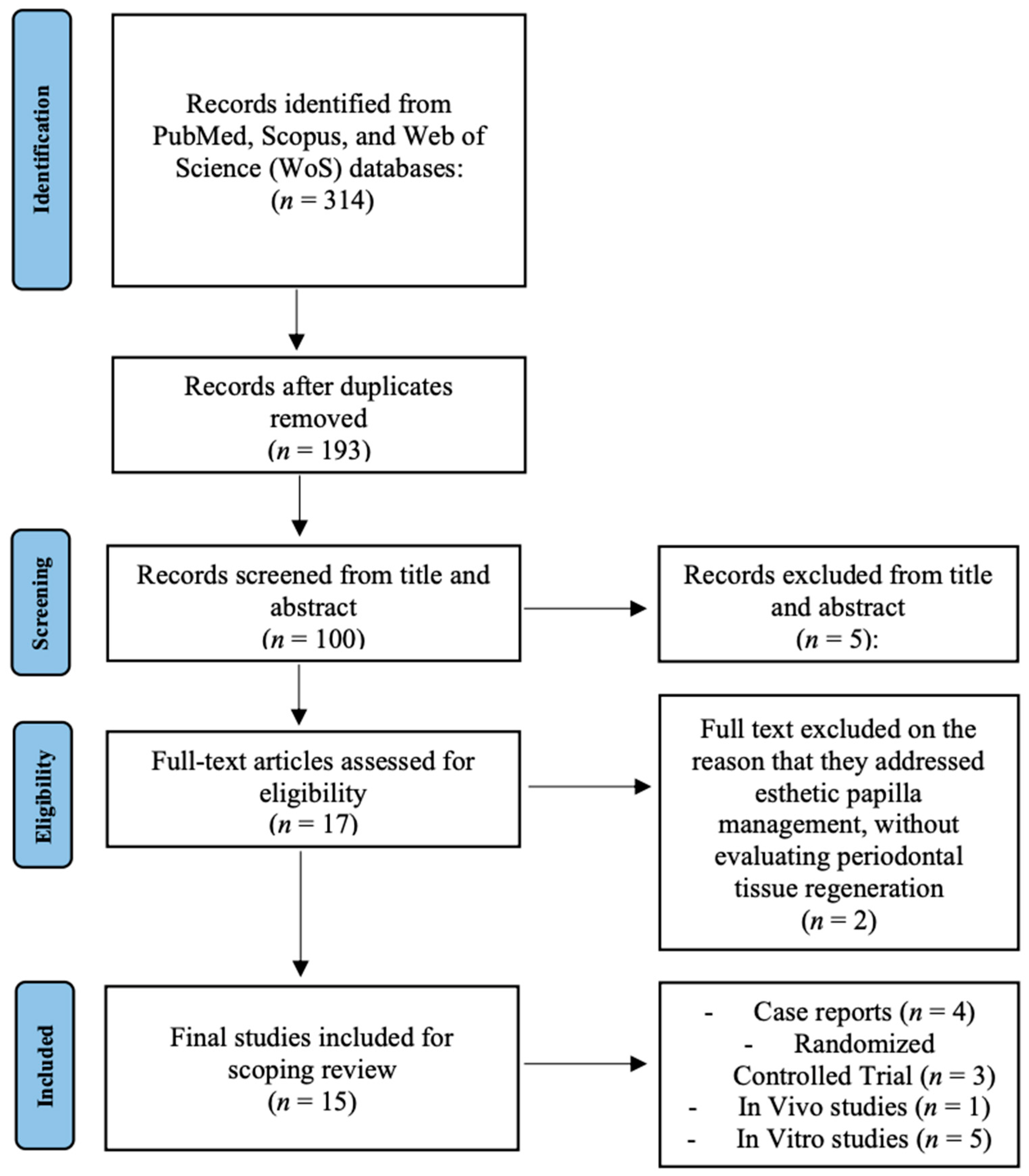

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2.3. Search Strategies and Information Source

2.2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.2.5. Methodological and Reporting Quality Assessment

2.2.6. Analysis of Included Studies

2.2.7. Methodological Appraisal of Randomized Controlled Trials

3. Results

3.1. Methodological Appraisal of Randomized Controlled Trials

3.2. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

| Author, Year | Study Design & Sample | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamauchi, 2017 [6] | In vitro study on PDLSCs obtained from human third molars, cultured under osteogenic conditions. | Cells irradiated with a high-power red LED at 650 nm, energy density of 8 J/cm2, applied in multiple sessions to simulate PBM therapy. | Non-irradiated PDLSCs cultured under the same conditions served as controls. | Assessed proliferation rate, ALP activity, calcium deposition, and ERK1/2 signaling pathway activation. | LED irradiation promoted PDLSC proliferation, significantly increased ALP activity and calcium deposition, and upregulated osteogenic marker expression. Activation of ERK1/2 confirmed a molecular mechanism underlying the observed effects. |

| El-Dahab, 2024 [18] | In vitro study on human PDLSCs isolated from extracted teeth and cultured under standard conditions. | Cells were irradiated with a diode laser at 970 nm using parameters consistent with PBM protocols. Irradiation was performed at multiple time points to assess cumulative effects on proliferation and differentiation. | Non-irradiated PDLSCs cultured in parallel were used as controls. | Cell proliferation assessed by CCK-8 assay; osteogenic differentiation evaluated via ALP activity, mineralized nodule formation, and gene expression of osteogenic markers. | Laser irradiation significantly enhanced PDLSC proliferation and osteogenic differentiation compared with controls, with greater mineralized nodule deposition, supporting the role of diode lasers in periodontal regeneration. |

| Aljabri, 2025 [19] | In vitro study using PDLSCs exposed to GMSCs conditioned medium, designed to mimic paracrine signaling in regeneration. | Diode laser at 980 nm applied under LLLT parameters. Irradiation was performed in conjunction with GMSCs conditioned medium to test synergistic effects. | PDLSCs without laser and without conditioned medium were used as baseline controls. | Cell viability, osteogenic differentiation markers (RUNX2, OCN, BMP-2), and activation of Wnt/TGF-β signaling were assessed. | The combination of GMSCs conditioned medium and laser irradiation significantly enhanced osteogenesis compared with controls. Upregulation of osteogenic markers and activation of Wnt/TGF-β pathway confirmed synergistic effects. |

| Wu, 2023 [20] | In vitro study on PDLSCs derived from extracted human teeth. | Cells irradiated with a Nd:YAG laser at sub-ablative low-energy settings (0.25–1.5 W, 30 s, MSP mode). Different power levels were tested to identify the optimal range for cell stimulation. | Non-irradiated PDLSCs served as controls. | Cell proliferation evaluated by CCK-8 assay, migration tested by Transwell assays, and gene/protein expression of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling assessed by RT-PCR and Western blot. | Nd:YAG laser irradiation at 1 W significantly enhanced PDLSC proliferation and migration compared to controls. These effects were mediated through SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling, indicating potential for improved stem cell homing in regenerative therapy. |

| Talebi-Ardakani, 2016 [21] | In vitro study on primary human gingival fibroblasts cultured under standard laboratory conditions. | Fibroblasts were exposed to Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers at sub-ablative energy settings, applied in a controlled in vitro environment. | Non-irradiated fibroblasts were used as controls. | Cell proliferation and viability were assessed by MTT assays. | Both Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG lasers increased fibroblast proliferation compared to controls, suggesting potential for enhanced soft tissue healing in periodontal therapy. |

| Author, Year | Study Design & Sample | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kalaivani, 2025 [22] | Ex vivo study on platelet concentrates (A-PRF and A-PRF+) prepared from human venous blood samples. | Diode laser irradiation at 630 nm applied in a non-contact mode for 15–20 s to stimulate growth factor release. | PRF and A-PRF samples not exposed to laser irradiation served as controls. | Quantification of PDGF-BB release using ELISA assays. | Laser irradiation significantly increased PDGF-BB release compared with non-irradiated controls, indicating that PBM enhances the regenerative potential of platelet concentrates. |

| Satish, 2023 [23] | Ex vivo study on periodontally compromised root surfaces collected from extracted human teeth. | Er,Cr:YSGG laser irradiation applied to root surfaces for smear layer removal and surface conditioning. | Root surfaces treated with EDTA or tetracycline, as well as untreated roots, were used as comparators. | Evaluation of smear layer removal and fibrin adhesion by SEM and histological analysis. | Laser irradiation effectively removed the smear layer and promoted fibrin adhesion, producing root surfaces more favorable for periodontal regeneration compared to conventional chemical conditioning methods. |

| Author, Year | Study Design & Model | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takemura, 2024 [24] | Animal study conducted on a rat model with surgically created periodontal defects. | Periodontal defects irradiated with Er:YAG laser in LLLT mode at sub-ablative parameters, repeated over the healing period. | Sham-irradiated defects served as controls. | Histological assessment of tissue repair, VEGF expression, angiogenesis, and new bone formation. | Er:YAG laser irradiation promoted angiogenesis and VEGF expression, leading to significantly greater new bone formation compared with controls, confirming its regenerative potential in vivo. |

| Author, Year | Study Design & Sample | Intervention | Comparator | Follow-Up | Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhardwaj, 2016 [28] | Case report on a single patient presenting with an intraosseous periodontal defect managed with regenerative surgery. | Treatment consisted of DBM graft combined with adjunctive LLLT using an 810 nm diode laser in PBM mode, applied post-surgically to stimulate healing. | No direct comparator; results were evaluated against conventional outcomes reported in the literature. | 12 months. | Clinical parameters (PD reduction, CAL gain) and radiographic bone fill. | The case showed a marked reduction in PD, significant CAL gain, and radiographic evidence of bone regeneration, supporting LLLT as an adjunct to grafting. |

| Cetiner, 2024 [25] | RCT including 40 intrabony defect sites in patients with chronic periodontitis. | Adjunctive diode laser at 970 nm for aPDT combined with LED PBM, applied alongside GTR with biomaterials. | Control group received GTR with biomaterials but no laser therapy. | 12 months. | PD, CAL, biochemical markers of bone metabolism. | Adjunctive laser therapy resulted in greater PD and CAL improvements and increased bone marker levels compared with the control group. |

| Dadas, 2025 [26] | RCT involving 45 patients with periodontitis undergoing SRP. | LANAP protocol with Nd:YAG laser combined with adjunctive LLLT applied after SRP. | SRP alone served as control. | 12 months. | PD, CAL, radiographic bone regeneration. | LANAP + LLLT produced superior clinical and radiographic outcomes compared with SRP alone, confirming enhanced regenerative effects. |

| Deepthi, 2024 [29] | Case report of one patient requiring preservation of a second molar affected by periodontitis. | Combined use of diode laser at 970 nm and PBM with adjunctive PRF. | Standard care approaches reported in the literature served as comparison. | 6 months. | PD, CAL, radiographic bone fill. | Laser combined with PRF reduced PD, improved CAL, and demonstrated radiographic regeneration, supporting tooth preservation. |

| Psg, 2025 [27] | RCT including 32 patients with intrabony periodontal defects. | Adjunctive LLLT using a diode laser during simplified papilla preservation flap surgery. | Control group underwent papilla preservation flap surgery without LLLT. | 6 months. | PD, CAL, molecular markers (RUNX2, BMP-2, COL1, OPN). | LLLT enhanced clinical improvements and upregulated osteogenic biomarkers, confirming both clinical and molecular regenerative benefits. |

| Puthalath, 2023 [30] | Case report of a patient with stage IV periodontitis requiring regenerative treatment. | Diode 940 nm laser-assisted curettage (LANAP-like protocol). | Conventional curettage outcomes described in the literature served as comparator. | 6 months. | PD, CAL, radiographic bone regeneration. | Laser-assisted curettage promoted periodontal healing and radiographic bone regeneration in advanced periodontitis. |

| Tan, 2022 [31] | Case report of two patients with periodontal bone defects treated with regenerative surgery. | Er:YAG laser applied in combination with A-PRF+. | Conventional regenerative approaches in the literature were used as comparators. | 36 months. | PD, CAL, radiographic bone stability. | Laser combined with A-PRF+ provided stable long-term PD reduction, CAL gain and radiographic bone regeneration over three years. |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Santonocito, S.; Polizzi, A.; Cavalcanti, R.; Lo Giudice, A.; Indelicato, F.; Isola, G. Impact of laser therapy on periodontal and peri-implant diseases: A review. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2022, 40, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.; Teughels, W.; Group A of European Workshop on Periodontology. Innovations in non-surgical periodontal therapy: Consensus report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35 (Suppl. S8), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behdin, S.; Monje, A.; Lin, G.H.; Edwards, B.; Othman, A.; Romanos, G.E. Effectiveness of laser application for periodontal surgical therapy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2015, 86, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, A.; Mizutani, K.; Schwarz, F.; Sculean, A.; Yukna, R.A.; Takasaki, A.A.; Romanos, G.E.; Taniguchi, Y.; Sasaki, K.M.; Zeredo, J.L.; et al. Periodontal and peri-implant wound healing following laser therapy. Periodontology 2000 2015, 68, 217–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; McGrath, C.; Jin, L.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y. The effectiveness of low-level laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A meta-analysis. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, N.; Taguchi, Y.; Kato, H.; Umeda, M. High-power, red-light-emitting diode irradiation enhances proliferation, osteogenic differentiation, and mineralization of human periodontal ligament stem cells via ERK signaling pathway. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gufran, K.; Alqahtani, A.; Alasqah, M.; Alsakr, A.; Alkharaan, H.; Alzahrani, H.G.; Almutairi, A. Effect of Er:YAG laser therapy in non-surgical periodontal treatment: An umbrella review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, A.; Mizutani, K.; Taniguchi, Y.; Lin, T.; Ohsugi, Y.; Mikami, R.; Katagiri, S.; Meinzer, W.; Iwata, T. Current status of Er:YAG laser in periodontal surgery. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2024, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slot, D.E.; Kranendonk, A.A.; Paraskevas, S.; Van der Weijden, F. The effect of a pulsed Nd:YAG laser in non-surgical periodontal therapy. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 1041–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elavarasu, S.; Naveen, D.; Thangavelu, A. Lasers in periodontics. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2012, 4 (Suppl. S2), S260–S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brindha, R. Low level laser therapy in periodontics: A review article. J. Acad. Dent. Educ. 2018, 4, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mathew, P.A.; More, V.; Pai, B.J. Lasers: Its role in periodontal regeneration. Health Inform. Int. J. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateson, M. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine: How to review and apply findings of healthcare research. Postgrad. Med. J. 2004, 80, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Stern, C.; Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Jordan, Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanin, F.; Moreira, M.S.; Pedroni, A.C.F.; Windlin, M.; Brugnera, A.P.; Brugnera Júnior, A.; Marques, M.M. Hemolasertherapy: A novel procedure for gingival papilla regeneration—Case report. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2018, 36, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mobadder, M.; Nammour, S. Photobiomodulation therapy in the management of “black triangles” due to the absence of the gingival interdental papilla. Cureus 2024, 16, e54682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dahab, M.M.A.; El Deen, G.N.; Shalash, M.; Gheith, M.; Abbass, A.; Aly, R.M. The efficacy of infrared diode laser in enhancing the regenerative potential of human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs). BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M.Y.; Alhazmi, Y.A.; Elsayyad, S.A.; Saber, S.M.; Shamel, M. Gingival stem cell-conditioned media and low-level laser therapy enhance periodontal ligament stem cell function by upregulating Wnt and TGF-β pathway components: An in vitro study. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2025, 11, e70151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Song, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, X.; Liu, T.; Wu, M. Effect of a low-energy Nd:YAG laser on periodontal ligament stem cell homing through the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi-Ardakani, M.R.; Torshabi, M.; Karami, E.; Arbabi, E.; Rezaei Esfahrood, Z. In vitro study of Er:YAG and Er,Cr:YSGG laser irradiation on human gingival fibroblast cell line. Acta Med. Iran. 2016, 54, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kalaivani, V.; Narayanan, V.; Ravishankar, P.L.; Ramkumar, K.M.; Ahmed, N.; Vinayachandran, D. A comparative evaluation of platelet-derived growth factor in a-PRF and a-PRF Plus, with and without low-level laser therapy—An ex vivo pilot study. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2025, 37, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, R.L.; Peter, M.R.; Bhaskar, A.; Vylopillil, R.; Balakrishnan, B.; Suresh, R. Comparative evaluation of fibrin network formation after root conditioning using Er,Cr:YSGG laser, EDTA, and tetracycline: A scanning electron microscopic study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2023, 14, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemura, S.; Mizutani, K.; Mikami, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Hakariya, M.; Sakaniwa, E.; Saito, N.; Kominato, H.; Kido, D.; Takeda, K.; et al. Enhanced periodontal tissue healing via VEGF expression following low-level erbium-doped:yttrium, aluminum, and garnet laser irradiation: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Periodontol. 2024, 95, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetiner, D.O.; Isler, S.C.; Ilikci-Sagkan, R.; Sengul, J.; Kaymaz, O.; Corekci, A.U. Adjunctive use of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, LED photobiomodulation, and ozone therapy in regenerative treatment of stage III/IV grade C periodontitis: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya Dadas, F.; Genc Kocaayan, S.; Saglam, M.; Dadas, O.F.; Koseoglu, S. Evaluating the efficacy of laser-assisted new attachment procedure and adjunctive low-level laser therapy in treating periodontitis: A single-blind randomized controlled clinical study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psg, P.; Sanjeev, K.; Subramanian, S.; Thanigaimalai, A.; Appukuttan, D. Clinical, radiographic and molecular efficacy of LLLT along with minimally invasive flaps in the regeneration of periodontal intrabony defects: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; George, J.P.; Remigus, D.; Khanna, D. Low-level laser therapy in the treatment of intra-osseous defect: A case report. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2016, 10, ZD06–ZD08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepthi, M.; Gowda, T.M.; Shah, R.; Kumar, A.B.T.; Priya, S. Salvaging the second molar with platelet-rich fibrin and photobiomodulation (970 nm diode laser) following third molar extraction. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2024, 28, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthalath, S.; Santhosh, V.C.; Nath, S.G.; Viswanathan, R. Rehabilitation and follow-up of a case of periodontitis—Generalized, stage IV, grade B, progressive, and with no risk factors. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2023, 14, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.S. Er:YAG laser and advanced PRF+ in periodontal diseases: Two case reports and review of the literature. World J. Clin. Cases 2022, 10, 12337–12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search String (Full Syntax) |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Periodontal Diseases”[MeSH] OR periodontitis[tiab] OR periodontal[tiab] OR “intrabony defect” [tiab] OR furcation[tiab]) AND (“Periodontal Regeneration”[MeSH] OR “tissue regeneration”[tiab] OR “guided tissue regeneration”[MeSH] OR GTR[tiab]) AND (“Lasers”[MeSH] OR laser[tiab] OR “Laser Therapy, Low-Level”[MeSH] OR photobiomodulation[tiab] OR LLLT[tiab] OR photodynamic[tiab] OR “Photochemotherapy”[MeSH] OR “Er:YAG”[tiab] OR “Er,Cr:YSGG”[tiab] OR Nd:YAG[tiab] OR diode[tiab] OR CO2[tiab] OR LANAP[tiab])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (periodontitis OR periodontal OR “intrabony defect” OR furcation) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“periodontal regeneration” OR “tissue regeneration” OR “guided tissue regeneration” OR GTR) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (laser OR “low level laser therapy” OR photobiomodulat OR LLLT OR photodynamic OR “Er:YAG” OR “Er,Cr:YSGG” OR “Nd:YAG” OR diode OR CO2 OR LANAP)) |

| Web of Science | TS = (periodontitis OR periodontal OR “intrabony defect” OR furcation) AND TS = (“periodontal regeneration” OR “tissue regeneration” OR “guided tissue regeneration” OR GTR) AND TS = (laser OR “low level laser therapy” OR photobiomodulation OR LLLT OR photodynamic OR “Er:YAG” OR “Er,Cr:YSGG” OR “Nd:YAG” OR diode OR CO2 OR LANAP) |

| Study | Randomization Reported | Blinding | Control Group Appropriate | Selective Outcome Reporting | Overall Appraisal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cetiner, 2024 [25] | Partially described | No blinding | Yes | Unclear | Moderate risk |

| Dadas, 2025 [26] | Reported | No blinding | Yes | Unclear | Moderate risk |

| Psg, 2025 [27] | Not clearly described | No blinding | Yes | Possible | High risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosisio, M.; Romeo, U.; Del Vecchio, A.; Giannì, A.B. Use of Laser in Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Medicina 2025, 61, 2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122199

Bosisio M, Romeo U, Del Vecchio A, Giannì AB. Use of Laser in Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122199

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosisio, Martina, Umberto Romeo, Alessandro Del Vecchio, and Aldo Bruno Giannì. 2025. "Use of Laser in Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122199

APA StyleBosisio, M., Romeo, U., Del Vecchio, A., & Giannì, A. B. (2025). Use of Laser in Periodontal Tissue Regeneration: A Scoping Review of Clinical and Experimental Evidence. Medicina, 61(12), 2199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122199