Flat Magnetic Stimulation in the Conservative Management of Mild Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. POP-Q Assessment

2.3. Intervention: Flat Magnetic Stimulation

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Consent and Questionnaire Administration

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Anatomical Outcomes

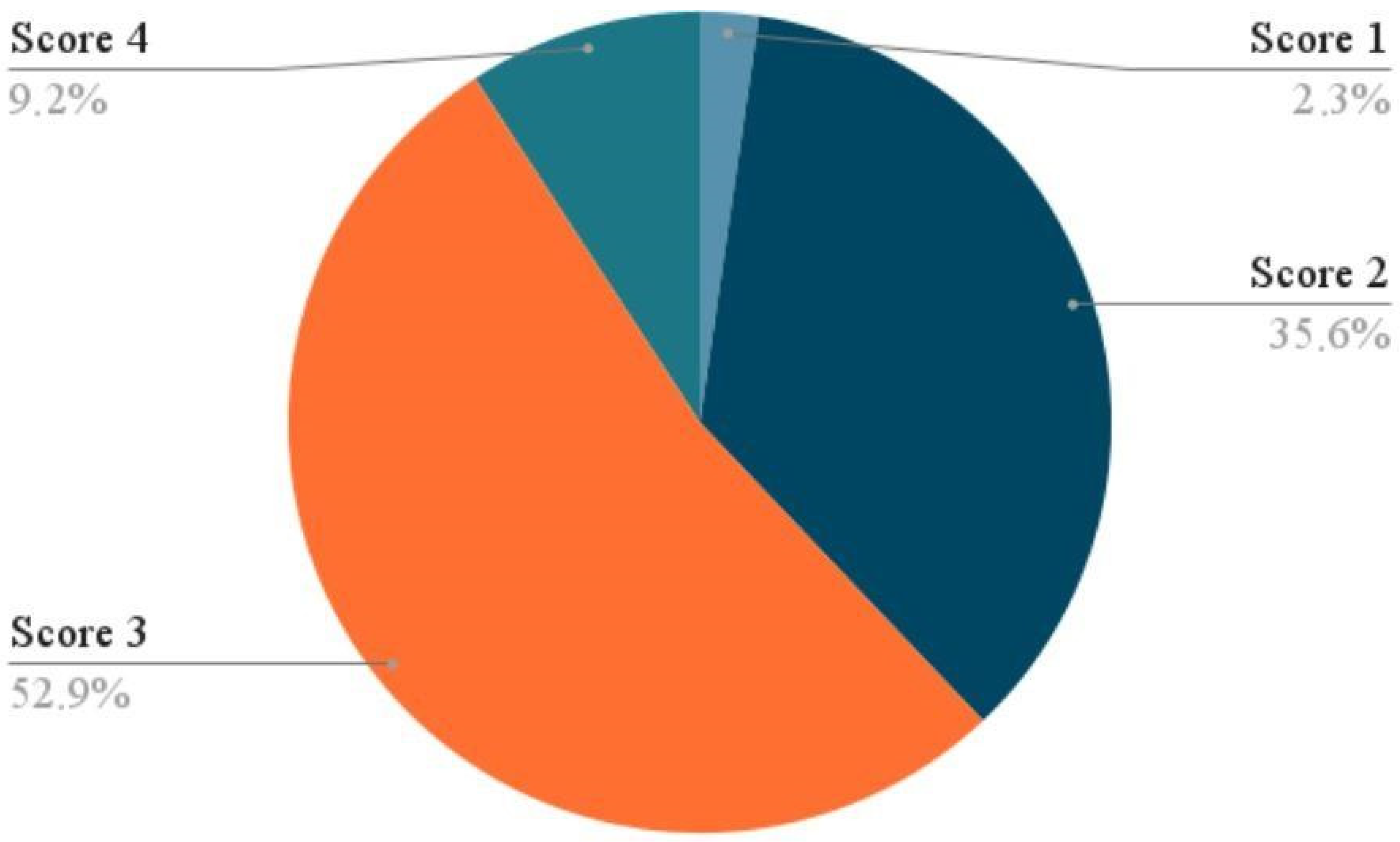

3.2. Subjective Outcomes (PGI-I Scores)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Schmid, C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD004014. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.; Feiner, B.; Baessler, K.; Christmann-Schmid, C.; Haya, N.; Brown, J. Surgery for women with apical vaginal prolapse. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2017, 28, 1785–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milsom, I.; Gyhagen, M. The prevalence of urinary incontinence. Climacteric 2019, 22, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, I.; Barber, M.D.; Burgio, K.L.; Kenton, K.; Meikle, S.; Schaffer, J.; Spino, C.; Whitehead, W.E.; Wu, J.; Brody, D.J.; et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 104, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, S.; Woodman, P.; O’BOyle, A.; Kahn, M.; Valley, M.; Bland, D.; Wang, W.; Schaffer, J. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): The distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, S.L.; Clark, A.; Nygaard, I.; Aragaki, A.; Barnabei, V.; McTiernan, A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women’s Health Initiative: Gravity and gravidity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M.D. Symptoms and outcome measures of pelvic organ prolapse. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 48, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.; Stark, D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 2011, CD003882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, C.; Hay-Smith, E.J.; Mac Habée-Séguin, G. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 2014, CD005654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegersma, M.; Panman, C.M.C.R.; Kollen, B.J.; Berger, M.Y.; Lisman-Van Leeuwen, Y.; Dekker, J.H. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training compared with watchful waiting in older women with symptomatic mild pelvic organ prolapse: Randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMJ 2014, 349, g7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, S.; Stark, D.; Glazener, C.; Dickson, S.; Barry, S.; Elders, A.; Frawley, H.; Galea, M.P.; Logan, J.; McDonald, A.; et al. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, S.; Glazener, C. Conservative management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. JAMA 2020, 324, 1680–1681. [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi, T.; Sakakibara, R.; Uchiyama, T.; Suda, S.; Hattori, T.; Ito, H.; Yasuda, K. Comparative study of the effects of magnetic versus electrical stimulation on inhibition of detrusor overactivity. Urology 2000, 56, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lay, A.H.; Das, A.K. The Role of Neuromodulation in Patients with Neurogenic Overactive Bladder. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2012, 13, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClurg, D.; Ashe, R.; Marshall, K.; Lowe-Strong, A. Comparison of pelvic floor muscle training, electromyography biofeedback, and neuromuscular electrical stimulation for bladder dysfunction in people with multiple sclerosis: A randomized pilot study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2006, 25, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Rezzan, G.; Costa, C.; Re, I.; Volontè, S.; Terzoni, S.; Frigerio, M.; Maruccia, S. Flat Magnetic Stimulation for Urge Urinary Incontinence. Medicina 2023, 59, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, M.; Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Marino, G.; Volontè, S.; Melocchi, T.; De Vicari, D.; Maruccia, S. Flat Magnetic Stimulation for Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Prospective Comparison Study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondo, A.; Murina, F.; Fusco, I. Treatment of Pelvic Floor Hypertonic Disorders with top Flat Magnetic Stimulation in Women with Vestibulodynia: A Pilot Study. J. Women’s Health Dev. 2022, 05, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, G.; Donolo, E.; Borghero, G.; Dessole, S. Conservative treatment of female urinary incontinence with functional magnetic stimulation. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 39, 491–494. [Google Scholar]

- Lukanović, D.; Kunič, T.; Batkoska, M.; Matjašič, M.; Barbič, M. Effectiveness of Magnetic Stimulation in the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Results of Our Study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bump, R.C.; Mattiasson, A.; Bø, K.; Brubaker, L.P.; DeLancey, J.O.; Klarskov, P.; Shull, B.L.; Smith, A.R. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 175, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ShahAli, S.; Bø, K.; Hejazi, A.; Hashemi, H.; Kharaji, G. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training on pelvic floor muscle morphometry in subjects with pelvic organ prolapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Women’s Health 2025, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braga, A.; Castronovo, F.; Caccia, G.; Papadia, A.; Regusci, L.; Torella, M.; Salvatore, S.; Scancarello, C.; Ghezzi, F.; Serati, M. Efficacy of 3 Tesla Functional Magnetic Stimulation for the Treatment of Female Urinary Incontinence. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcin, I.; Bump, R.C. Validation of two global impression questionnaires for incontinence. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petros, P.E.; Ulmsten, U. An integral theory of female urinary incontinence: Experimental and clinical considerations. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. Suppl. 1990, 153, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Zalm, P.J.V.; Pelger, R.C.; Stiggelbout, A.M.; Elzevier, H.W.; Nijeholt, G.A.L.À. Effects of magnetic stimulation in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction. BJU Int. 2006, 97, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Re, I.; De Vicari, D.; Costa, C.; Frigerio, M.; Da Pozzo, B.; Maruccia, S. Flat Magnetic Stimulation for Anal Incontinence: A Prospective Study. Int. J. Womens Health 2025, 17, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quek, P. A critical review on magnetic stimulation: What is its role in the management of pelvic floor disorders? Curr. Opin. Urol. 2005, 15, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopopolo, G.; Salsi, B.; Banfi, A.; Isaza, P.G.; Fusco, I. Is It Possible to Improve Urinary Incontinence and Quality of Life in Female Patients? A Clinical Evaluation of the Efficacy of Top Flat Magnetic Stimulation Technology. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.; Liong, M.L.; Leong, W.S.; Khan, N.A.K.; Yuen, K.H. Magnetic stimulation for stress urinary incontinence: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Pavčnik, M.; Lukanović, A.; Matjašič, M.; Lukanović, D. Magnetic stimulation in the treatment of female urgency urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2023, 34, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, M.; Cola, A.; De Vicari, D.; Costa, C.; La Greca, G.; Vigna, A.; Volontè, S.; Frigerio, M.; Terzoni, S.; Maruccia, S. Changes in Pelvic Floor Ultrasonographic Features after Flat Magnetic Stimulation in Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain and Levator Ani Muscle Hypertonicity. Medicina 2024, 60, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Rezzan, G.; Costa, C.; Melocchi, T.; De Vicari, D.; Terzoni, S.; Frigerio, M.; Maruccia, S. Flat Magnetic Stimulation for Stress Urinary Incontinence: A 3-Month Follow-Up Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value (Mean ± SD or n, %) |

|---|---|

| Number of participants | 87 |

| Age, years | 59.1 ± 6.4 (range: 30–75) |

| Parity (number of vaginal births) | 2 |

| Body mass index (BMI), kg/m2 | 23.4 ± 2.6 |

| POP stage (POP-Q) | All stage ≤ 2 |

| Predominant compartment | Anterior vaginal wall |

| POP-Q Point | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Post-Treatment (Mean ± SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | −0.3 ± 1.2 | −0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.03 |

| Ba | −0.3 ± 1.3 | −0.7 ± 1.3 | 0.04 |

| C | −5.4 ± 2.5 | −5.5 ± 2.4 | 0.59 |

| Ap | −1.1 ± 1.3 | −1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.42 |

| Bp | −1.2 ± 1.4 | −1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Vicari, D.; Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Amatucci, N.; Carrara, S.; Frigerio, M. Flat Magnetic Stimulation in the Conservative Management of Mild Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Retrospective Observational Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122198

De Vicari D, Barba M, Cola A, Amatucci N, Carrara S, Frigerio M. Flat Magnetic Stimulation in the Conservative Management of Mild Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Retrospective Observational Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122198

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Vicari, Desirèe, Marta Barba, Alice Cola, Nicola Amatucci, Sebastiano Carrara, and Matteo Frigerio. 2025. "Flat Magnetic Stimulation in the Conservative Management of Mild Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Retrospective Observational Study" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122198

APA StyleDe Vicari, D., Barba, M., Cola, A., Amatucci, N., Carrara, S., & Frigerio, M. (2025). Flat Magnetic Stimulation in the Conservative Management of Mild Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Retrospective Observational Study. Medicina, 61(12), 2198. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122198