Home Monitoring for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review of the Development and Implementation of Digital Health Solutions over a 25-Year Scientific Journey

Abstract

1. Introduction

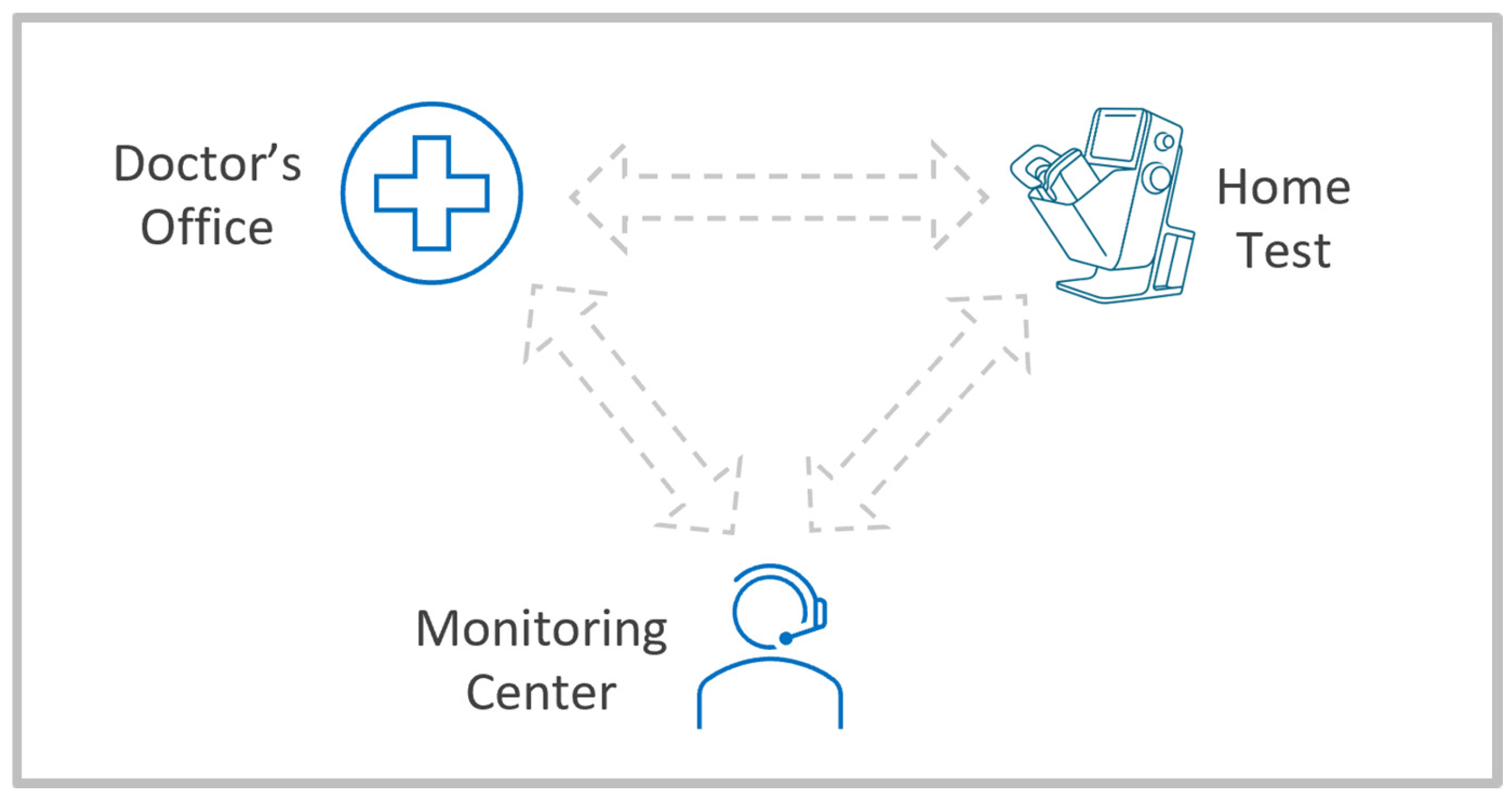

- Acceptable system performance addressing clinical needs, including a user interface, both hardware ergonomics and a software application, and a tele-connected device that can be self-installed and self-operated by the target population with a chronic retinal disease in a home environment.

- Automated analytics capabilities that can process large volumes of data from near-daily patient monitoring in support of a prescribing physician’s review and utilization of the data.

- Efficient remote patient engagement and support through a physician supervised digital healthcare provider entity. Such an entity should maintain ongoing relationships with a large number of patients under the care of a large number of clinics and physicians who prescribe the monitoring program.

- Low-cost medical device and data management solutions that can justify the use by a single patient, and a digital healthcare business model that allows proper compensation for both the technical services of the monitoring provider and the professional services of the prescribing physician.

2. Dry AMD

3. Wet AMD

4. Future Directions for Home Monitoring

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMD | Age-related Macular Degeneration |

| CMS | Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

| CONAN | Consensus Nomenclature for Reporting Neovascular AMD Data |

| CPT | Current Procedural Terminology |

| CSCR | Central Serous Chorioretinopathy |

| CST | Central Subfield Thickness |

| DME | Diabetic Macular Edema |

| DRCR | Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research |

| FA | Fluorescein Angiography |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FSH | ForeseeHome |

| HRS | Hypo Reflective Spaces |

| IDTF | Independent Diagnostics Testing Facility |

| MCPT | Macular Computerized Psychophysical Test |

| NOA | Notal OCT Analyzer |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| PK/PD | Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic |

| PHP | Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry |

| RCV | Reference Change Value |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| SD | Spectral Domain |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

| T&E | Treat and Extend |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors |

References

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assink, J.J.M.; Klaver, C.C.W.; Houwing-Duistermaat, J.J.; Wolfs, R.C.W.; van Duijn, C.M.; Hofman, A.; de Jong, P.T. Heterogeneity of the genetic risk in age-related macular disease. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, P.K.; Brown, D.M.; Zhang, K.; Hudson, H.L.; Holz, F.G.; Shapiro, H.; Schneider, S.; Acharya, N.R. Ranibizumab for Predominantly Classic Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration: Subgroup Analysis of First-year ANCHOR Results. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 850–857.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.Y.; Lee, C.S.; Butt, T.; Xing, W.; Johnston, R.L.; Chakravarthy, U.; Egan, C.; Akerele, T.; McKibbin, M.; Downey, L.; et al. UK AMD EMR USERS GROUP REPORT V: Benefits of initiating ranibizumab therapy for neovascular AMD in eyes with vision better than 6/12. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 99, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.C.; Kleinman, D.M.; Lum, F.C.; Heier, J.S.; Lindstrom, R.L.; Orr, S.C.; Chang, G.C.; Smith, E.L.; Pollack, J.S. Baseline Visual Acuity at Wet AMD Diagnosis Predicts Long-Term Vision Outcomes: An Analysis of the IRIS Registry. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2020, 51, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.Y.C.; Saxena, N.; Gan, A.; Wong, T.Y.; Gillies, M.C.; Chakravarthy, U.; Cheung, C.M.G. Detrimental Effect of Delayed Re-treatment of Active Disease on Outcomes in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2020, 4, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, A. The Significance of Early Detection of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina 2007, 27, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.C.; Albini, T.A.; Brown, D.M.; Boyer, D.S.; Regillo, C.D.; Heier, J.S. The Potential Importance of Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration When Visual Acuity Is Relatively Good. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westheimer, G. Visual acuity and hyperacuity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1975, 14, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoch, J.M. Hyperacuity Perimetry. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1984, 102, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; Danis, R.P.; Domalpally, A.; Heier, J.S.; Kim, J.E.; Garfinkel, R.A. Randomized trial of the ForeseeHome monitoring device for early detection of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. The HOme Monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study design—HOME Study report number 1. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2014, 37, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenstein, A.; Malach, R.; Goldstein, M.; Leibovitch, I.; Barak, A.; Baruch, E.; Alster, Y.; Rafaeli, O.; Avni, I.; Yassur, Y. Replacing the Amsler grid. Ophthalmology 2003, 110, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry Research Group. Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PreView PHP) for Detecting Choroidal Neovascularization Study. Ophthalmology 2005, 112, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.; Loewenstein, A.; Barak, A.; Pollack, A.; Bukelman, A.; Katz, H.; Springer, A.; Schachat, A.P.; Bressler, N.M.; Bressler, S.B.; et al. Results of a Multicenter Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter for Detection of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina 2005, 25, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.V.; Gower, E.W.; Cassard, S.D.; Boyer, D.; Bressler, N.M.; Bressler, S.B.; Heier, J.S.; Jefferys, J.L.; Singerman, L.J.; Solomon, S.D. Detection of New-Onset Choroidal Neovascularization Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Grattan, J.; Shi, Y.; Young, G.; Muldrew, A.; Chakravarthy, U. Functional and Morphologic Benefits in Early Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Using the Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter. Retina 2011, 31, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querques, G.; Querques, L.; Rafaeli, O.; Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Bandello, F.; Souied, E.H. Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter as a Functional Tool for Monitoring Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Patients Treated by Intravitreal Ranibizumab. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stur, M.; Manor, Y. Long-Term Monitoring of Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2010, 41, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Pahk, P.; Blaha, G.R.; Spindel, G.P.; Alster, Y.; Rafaeli, O.; Marx, J.L. Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry to Detect Hydroxychloroquine Retinal Toxicity. Retina 2009, 29, 1188–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querques, G.; Atmani, K.; Bouzitou-Mfoumou, R.; Leveziel, N.; Massamba, N.; Souied, E.H. Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter in Best Vitelliform Macular Dystrophy. Retina 2011, 31, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.H.; Kim, D.; Park, T.K.; Han, J.R.; Kim, H.; Nam, W. Preferential hyperacuity perimeter and prognostic factors for metamorphopsia after idiopathic epiretinal membrane surgery. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 155, 109–117.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querques, G.; Berboucha, E.; Leveziel, N.; Pece, A.; Souied, E.H. Preferential hyperacuity perimeter in assessing responsiveness to ranibizumab therapy for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 95, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Das, R.; Shi, Y.; Silvestri, G.; Chakravarthy, U. Distortion Maps from Preferential Hyperacuity Perimetry are Helpful in Monitoring Functional Response to Lucentis Therapy. Retina 2009, 29, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenstein, A. Macular Diseases: Moving the Battlefield to the Patient’s Home. Retina 2011, 31, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, R.E.; Sivaprasad, S.; Wickens, R.; O’cOnnor, S.; Gidman, E.; Ward, E.; Treanor, C.; Peto, T.; Burton, B.J.L.; Knox, P.; et al. Home-Monitoring Vision Tests to Detect Active Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2024, 142, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, D.L.C.; de Ávila, M.P.; Cialdini, A.P. Comparison of the original Amsler grid with the preferential hyperacuity perimeter for detecting choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2007, 70, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kampmeier, J.; Zorn, M.; Lang, G.; Botros, Y.; Lang, G. Comparison of Preferential Hyperacuity Perimeter (PHP) test and Amsler grid test in the diagnosis of different stages of age-related macular degeneration. Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 2006, 223, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossland, M.; Rubin, G. The Amsler chart: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 391–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, R.; Kynn, M.G. Macular function surveillance revisited. Optom.-J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 2008, 79, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaprasad, S.; Banister, K.; Azuro-Blanco, A.; Goulao, B.; Cook, J.A.; Hogg, R.; Scotland, G.; Heimann, H.; Lotery, A.; Ghanchi, F.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Monitoring Tests of Fellow Eyes in Patients with Unilateral Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, A.; Ferencz, J.R.; Lang, Y.; Yeshurun, I.; Pollack, A.; Siegal, R.; Lifshitz, T.; Karp, J.; Roth, D.; Bronner, G.; et al. Toward Earlier Detection of Choroidal Neovascularization Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina 2010, 30, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.; Clemons, T.; SanGiovanni, J.P. Lutein + Zeaxanthin and Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA 2013, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; Danis, R.P.; Domalpally, A.; Heier, J.S.; Kim, J.E.; Garfinkel, R.; AREDS2-HOME Study Research Group. Randomized trial of a home monitoring system for early detection of choroidal neovascularization home monitoring of the eye (HOME) study. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Harrington, M.; Bressler, S.B.; Elman, M.J.; Kim, J.E.; Garfinkel, R.; Heier, J.S.; Brucker, A.; Boyer, D.; et al. Effectiveness of Different Monitoring Modalities in the Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retina 2016, 36, 1542–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domalpally, A.; Clemons, T.E.; Bressler, S.B.; Danis, R.P.; Elman, M.; Kim, J.E.; Brown, D.; Chew, E.Y. Imaging Characteristics of Choroidal Neovascular Lesions in the AREDS2-HOME Study: Report Number 4. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2019, 3, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikitmongkol, V.; Bressler, N.M.; Bressler, S.B. Early Detection of Choroidal Neovascularization Facilitated with a Home Monitoring Program in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2015, 9, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.P. The ForeSeeHome Device and the HOME Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014, 132, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.C.; Heier, J.S.; Holekamp, N.M.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Ladd, B.; Awh, C.C.; Singh, R.P.; Sanborn, G.E.; Jacobs, J.H.; Elman, M.J.; et al. Real-World Performance of a Self-Operated Home Monitoring System for Early Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, M.; Reddy, S.; Elman, M.J.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Ladd, B.; Wagner, A.L.; Sanborn, G.E.; Jacobs, J.H.; Busquets, M.A.; Chew, E.Y. Analysis of the Long-term Visual Outcomes of ForeseeHome Remote Telemonitoring. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2022, 6, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenborn, J.S.; Clemons, T.; Regillo, C.; Rayess, N.; Liffmann Kruger, D.; Rein, D. Economic Evaluation of a Home-Based Age-Related Macular Degeneration Monitoring System. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017, 135, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.C.; Schechet, S.A.; Mathai, M.; Reddy, S.; Elman, M.J.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Ladd, B.; Wagner, A.L.; Sanborn, G.E.; Jacobs, J.H.; et al. The Predictive Value of False-Positive ForeseeHome Alerts in the ALOFT Study. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2023, 7, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vemulakonda, G.A.; Bailey, S.T.; Kim, S.J.; Kovach, J.L.; Lim, J.I.; Ying, G.; Flaxel, C.J. Age-Related Macular Degeneration Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, P1–P74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, J.; Huang, D. Foreword: 25 Years of Optical Coherence Tomography. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, OCTi–OCTii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.I.; Ko, S.; McAllister, M.; Faux, N.; Bawa, K.; Mearns, E.; Patel, S.; Spicer, G.; Martinez, A.; Tabano, D. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for the management of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Eye 2025, 39, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Brown, D.M.; Chong, V.; Korobelnik, J.-F.; Kaiser, P.K.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Kirchhof, B.; Ho, A.; Ogura, Y.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; et al. Intravitreal Aflibercept (VEGF Trap-Eye) in Wet Age-related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2537–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykoff, C.C.; Ou, W.C.; Brown, D.M.; Croft, D.E.; Wang, R.; Payne, J.F.; Clark, W.L.; Abdelfattah, N.S.; Sadda, S.R. Randomized Trial of Treat-and-Extend versus Monthly Dosing for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2017, 1, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, U.; Goldenberg, D.; Young, G.; Havilio, M.; Rafaeli, O.; Benyamini, G.; Loewenstein, A. Automated Identification of Lesion Activity in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 1731–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.; Havilio, M.; Loewenstein, A.; Rafaeli, O. A novel AI-based algorithm for quantifying volumes of retinal pathologies in OCT scans. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Ophthalmology Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy, U.; Havilio, M.; Syntosi, A.; Pillai, N.; Wilkes, E.; Benyamini, G.; Best, C.; Sagkriotis, A. Impact of macular fluid volume fluctuations on visual acuity during anti-VEGF therapy in eyes with nAMD. Eye 2021, 35, 2983–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur, D.; Wright, D.M.; Gonen, M.S.; Shor, R.; Wen, Q.; Benyamini, G.; Havilio, M.; Ben-Nun, M.; Look, S.; Dor, O.; et al. The British-Israeli Project for Algorithm-Based Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Deep Learning Integration for Real-World Data Management and Analysis. Ophthalmologica 2025, 248, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.D.; Clemons, T.E.; Domalpally, A.; Elman, M.J.; Havilio, M.; Agrón, E.; Benyamini, G.; Chew, E.Y. Retinal Specialist versus Artificial Intelligence Detection of Retinal Fluid from OCT. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.A.; Khanani, A.M.; Khan, H.; Lauer, E.; Khanani, I.; Mojumder, O.; Khanani, Z.A.; Khan, H.; Gahn, G.M.; Graff, J.T.; et al. Retinal fluid quantification using a novel deep learning algorithm in patients treated with faricimab in the TRUCKEE study. Eye 2025, 39, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, T.D.L.; Chakravarthy, U.; Loewenstein, A.; Chew, E.Y.; Schmidt-Erfurth, U. Automated Quantitative Assessment of Retinal Fluid Volumes as Important Biomarkers in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 224, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.E.; Tomkins-Netzer, O.; Elman, M.J.; Lally, D.R.; Goldstein, M.; Goldenberg, D.; Shulman, S.; Benyamini, G.; Loewenstein, A. Evaluation of a self-imaging SD-OCT system designed for remote home monitoring. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, T.D.L.; Goldstein, M.; Goldenberg, D.; Zur, D.; Shulman, S.; Loewenstein, A. Prospective, Longitudinal Pilot Study: Daily Self-Imaging with Patient-Operated Home OCT in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2021, 1, 100034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Holekamp, N.M.; Heier, J.S. Prospective, Longitudinal Study: Daily Self-Imaging with Home OCT for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2022, 6, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, J.; Steiert, B. Optimizing Early Ophthalmology Clinical Trials: Home OCT and Modeling Can Reduce Sample Size by 20% to 40%. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, K.J.; Calhoun, C.; Maguire, M.G.; Glassman, A.R.; Mein, C.E.; Baskin, D.E.; Vieyra, G.; Jampol, L.M.; Chica, M.A.; Sun, J.K.; et al. Home OCT Imaging for Newly Diagnosed Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Feasibility Study. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2024, 8, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Liu, Y.; Holekamp, N.M.; Ali, M.H.; Astafurov, K.; Blinder, K.J.; Busquets, M.A.; Chica, M.A.; Elman, M.J.; Fein, J.G.; et al. Clinical Use of Home OCT Data to Manage Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J. VitreoRetin. Dis. 2024, 9, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeb Center for Health Research. Home OCT-Guided Treatment Versus Treat and Extend for the Management of Neovascular AMD (DRCR Protocol AO CT.gov NCT05904028); Jaeb Center for Health Research: Tampa, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp, N.M.; de Beus, A.M.; Clark, W.L.; Heier, J.S. Prospective trial of Home OCT guided management of treatment experienced nAMD patients. Retina 2024, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faes, L.; Holekamp, N.; Benyamini, G.; Nahen, K.; Mohan, N.; Freund, K.B. Home Optical Coherence Tomography-guided Management of Type 3 Macular Neovascularization. Retin. Cases Brief Rep. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, N.M. Home OCT and Sustained Delivery Approaches, a Perfect Marriage. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 277, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Holekamp, N.M.; Busquets, M.A.; Elman, M.J.; Schechet, S.A.; Ladd, B.S.; Kapoor, K.G.; Schneider, E.W.; Leung, E.H.; Danis, R.P.; et al. Pivotal Trial Validating Usability and Visualization Performance of Home OCT in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: Report 1. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 5, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.W.; Heier, J.S.; Holekamp, N.M.; Busquets, M.A.; Wagner, A.L.; Mukkamala, S.K.; Riemann, C.D.; Lee, S.Y.; Joondeph, B.C.; Houston, S.S.; et al. Pivotal Trial towards Effectiveness of Self-Administered OCT in Neovascular Age-related Macular Degeneration. Report Number 2—Artificial Intelligence Analytics. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 5, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, T.; Leung, E.H.; Mukkamala, S.K.; Taban, M.R.; Havilio, M.; Nahen, K.; Mohan, N.; Benyamini, G.; Keenan, T.D. Longitudinal Validation of the Artificial Intelligence Algorithm in Home OCT for Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Report 3. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 100907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Long, K.; Chen, C.; Yauch, L.; Anegondi, N.; Indjeian, V.; Elliott, M.; Liu, J.; Sim, D.; Ferrara, D.; et al. Evaluation of Home OCT in Clinical Trial for Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. In Proceedings of the American Academy of Ophthalmology Meeting, Orlando, FL, USA, 18–20 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, B.-H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.-Y. Twenty Years of Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapeutics in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Busquets, M.A.; Garfinkel, R.A.; Sambhara, D.; Mohan, N.; Nahen, K.; Benyamini, G.; Loewenstein, A. Home Monitoring for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review of the Development and Implementation of Digital Health Solutions over a 25-Year Scientific Journey. Medicina 2025, 61, 2193. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122193

Busquets MA, Garfinkel RA, Sambhara D, Mohan N, Nahen K, Benyamini G, Loewenstein A. Home Monitoring for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review of the Development and Implementation of Digital Health Solutions over a 25-Year Scientific Journey. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2193. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122193

Chicago/Turabian StyleBusquets, Miguel A., Richard A. Garfinkel, Deepak Sambhara, Nishant Mohan, Kester Nahen, Gidi Benyamini, and Anat Loewenstein. 2025. "Home Monitoring for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review of the Development and Implementation of Digital Health Solutions over a 25-Year Scientific Journey" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2193. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122193

APA StyleBusquets, M. A., Garfinkel, R. A., Sambhara, D., Mohan, N., Nahen, K., Benyamini, G., & Loewenstein, A. (2025). Home Monitoring for the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Review of the Development and Implementation of Digital Health Solutions over a 25-Year Scientific Journey. Medicina, 61(12), 2193. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122193