Electrocardiogram-Alterations and Increasing Cardiac Enzymes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting—When Can We Expect Significant Findings in Coronary Angiography?

Abstract

1. Introduction

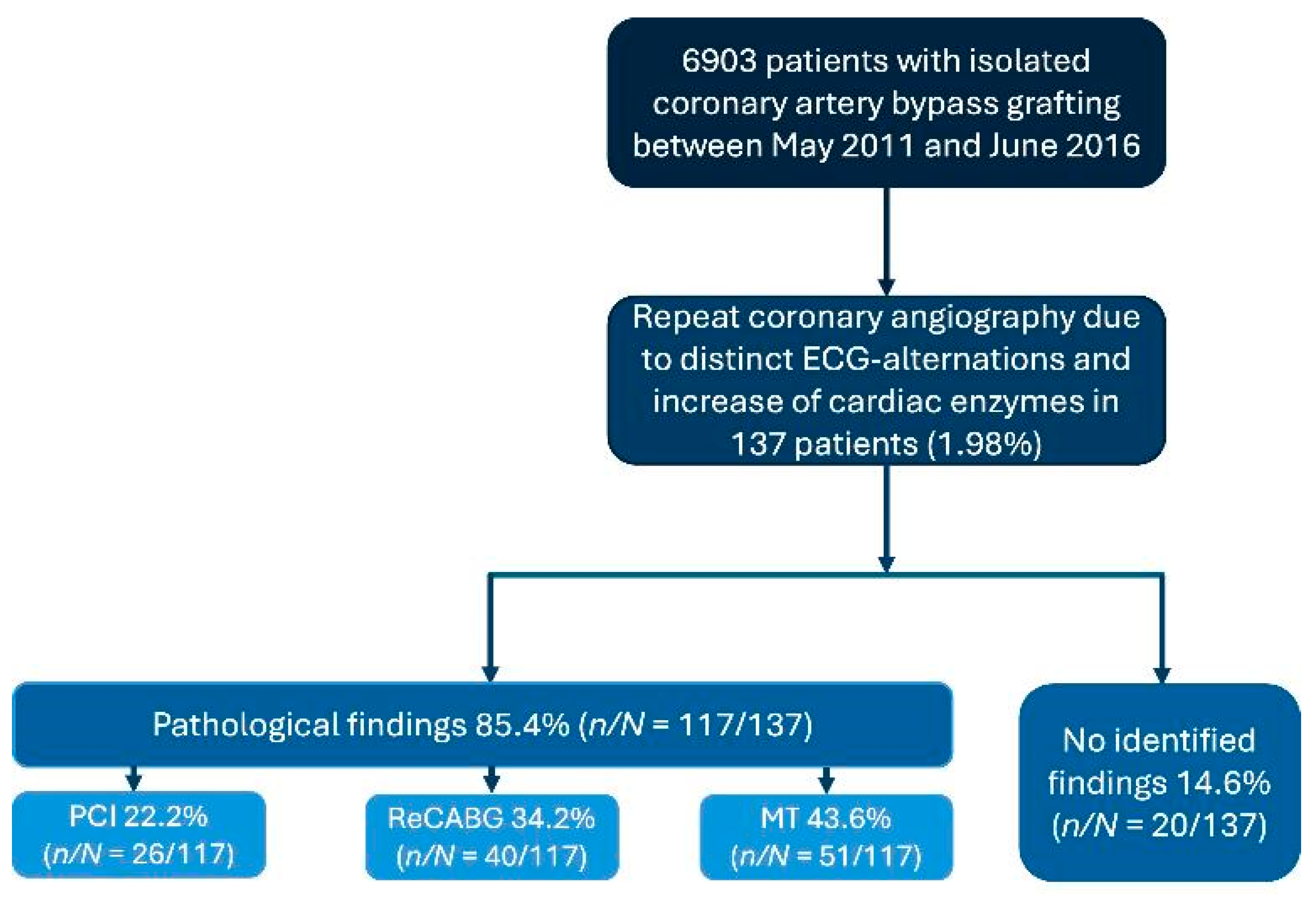

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Design

2.2. Decision-Making for Repeat Coronary Angiography

2.3. Study Endpoints

2.4. Data Analysis and Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Patient Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Procedural and Intraoperative Data

3.3. Angiographic Findings

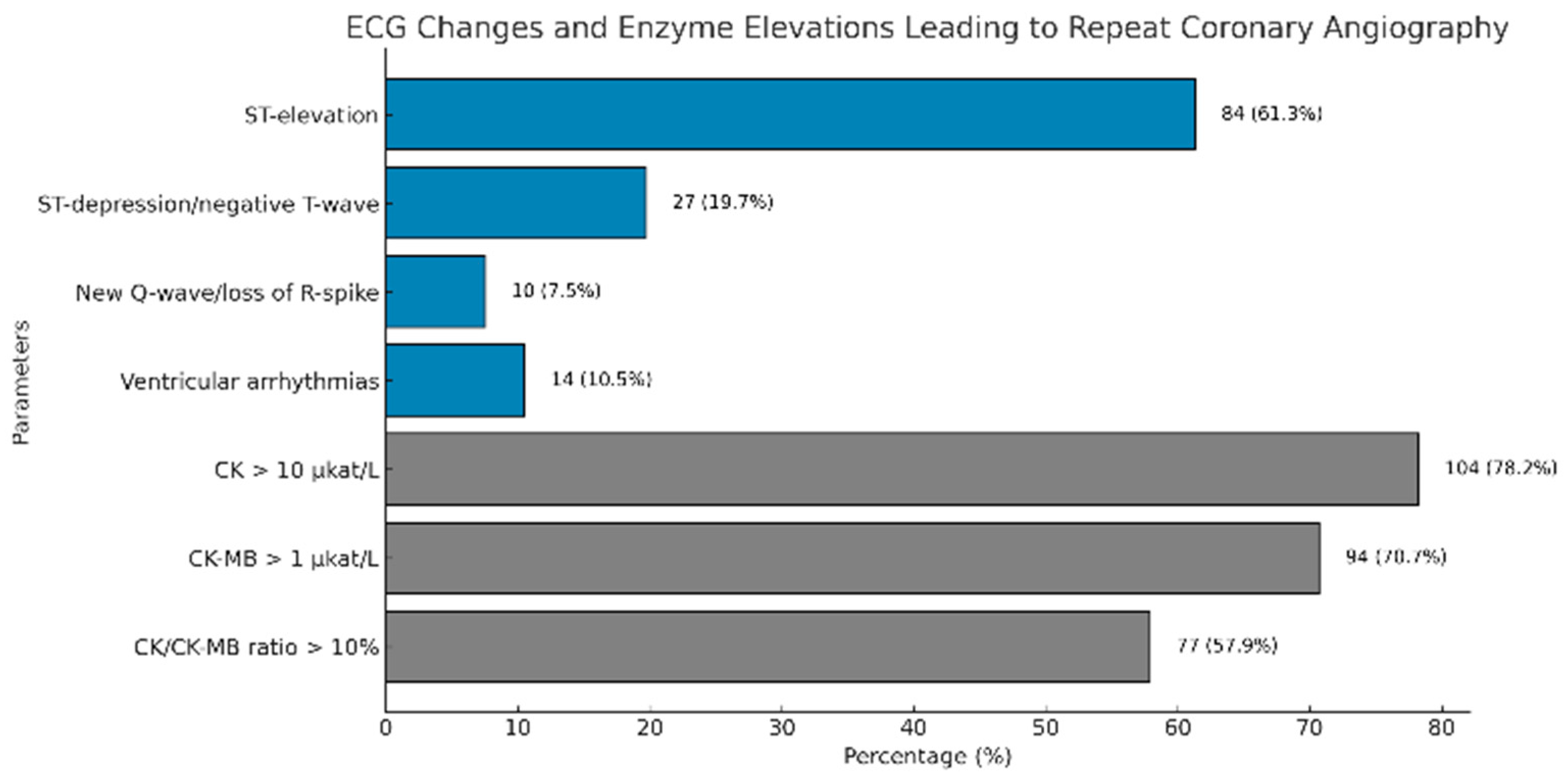

3.4. ECG Changes and Enzyme Elevations Leading to Repeat Coronary Angiography

3.5. Correlation Between Angiographic Findings and ECG Changes

3.6. Correlation Between Angiographic Findings and CK-, CK-MB-, and CK/CK-MB-Excursion

3.7. Correlation Between Angiographic Finding and Combination of ECG Changes and CK-MB-Excursion

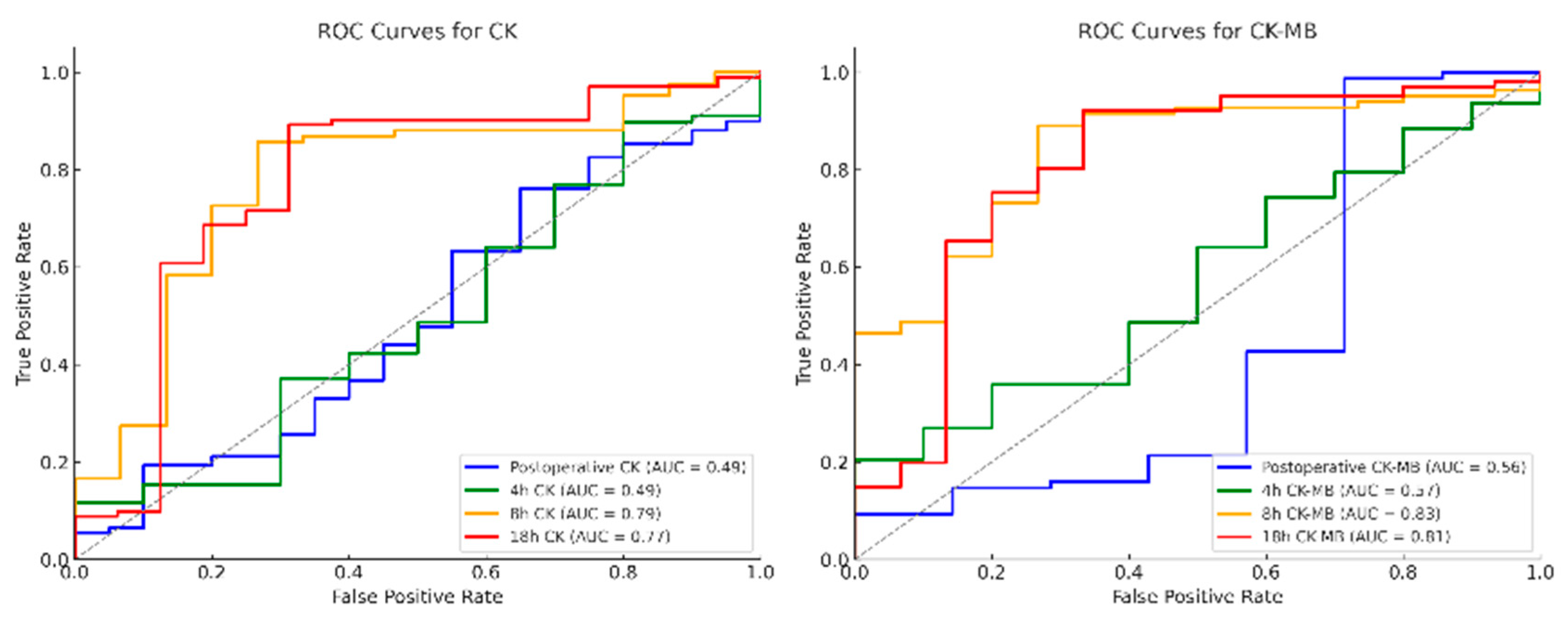

3.8. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis of Postoperative Enzyme Course of CK, CK-MB and CK/CK-MB Ratio

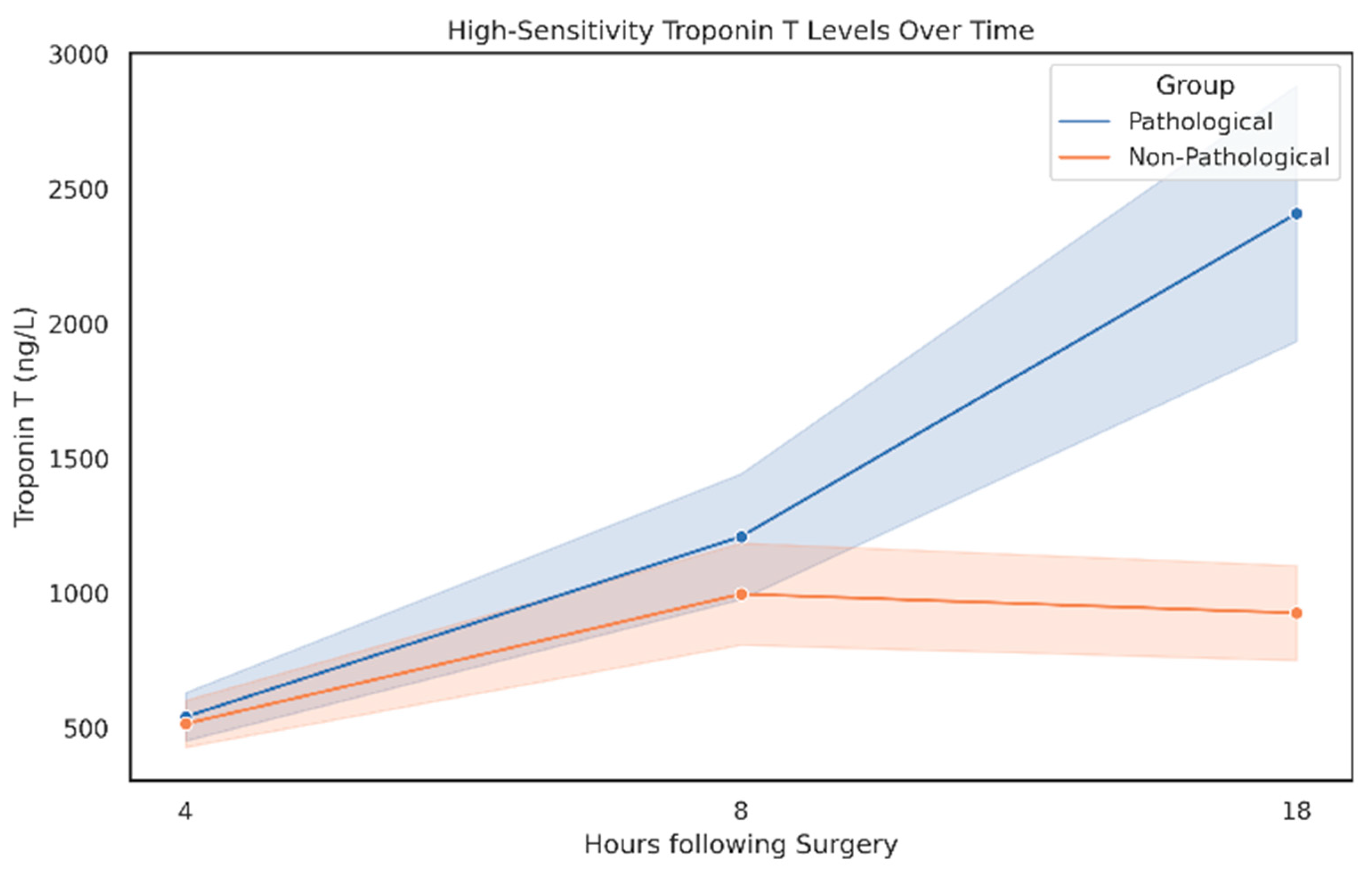

3.9. High-Sensitivity Troponin T (hsTnT) Enzyme Course with Respect to Angiographic Findings

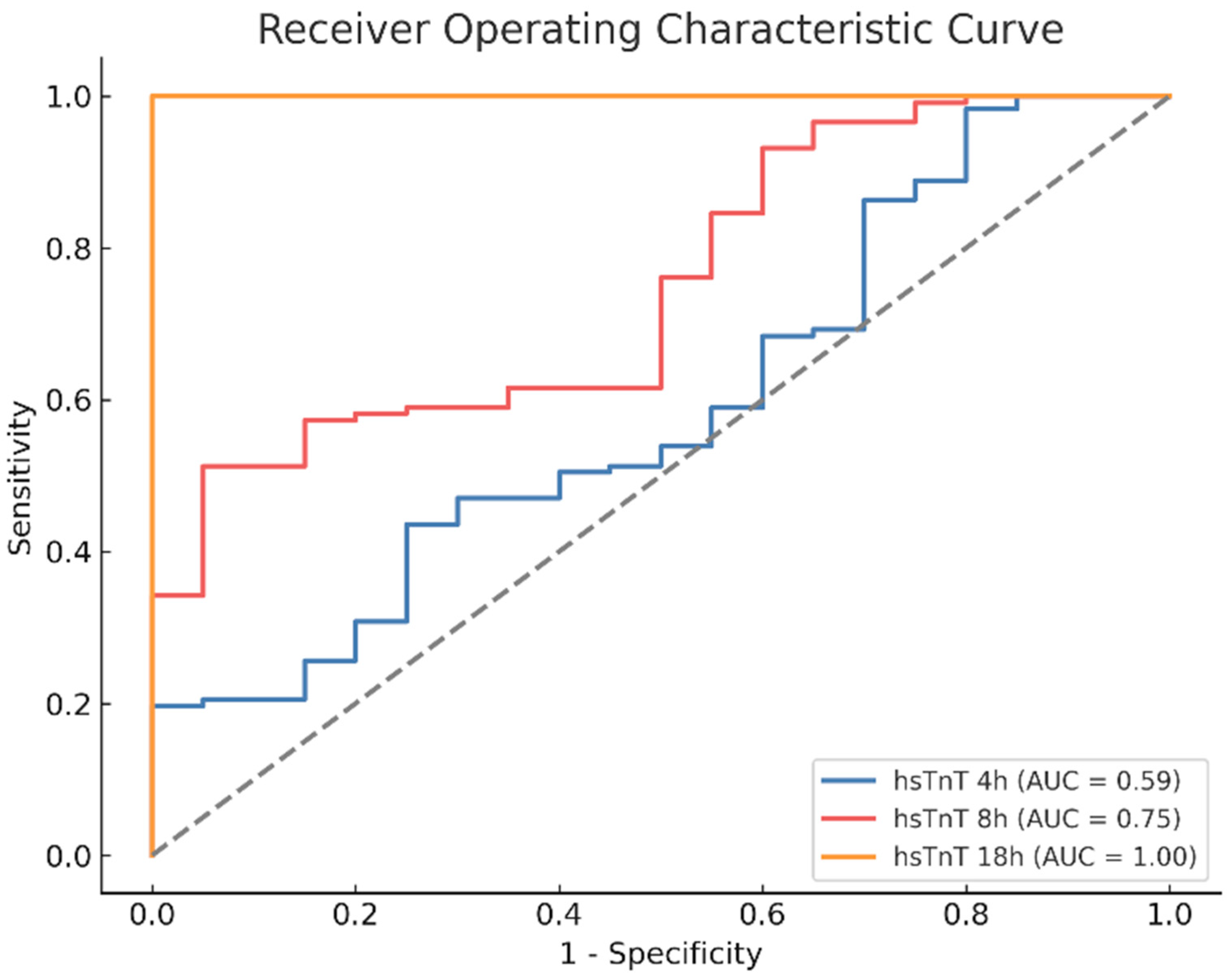

3.10. ROC Analysis of Postoperative Enzyme Course of hsTnT

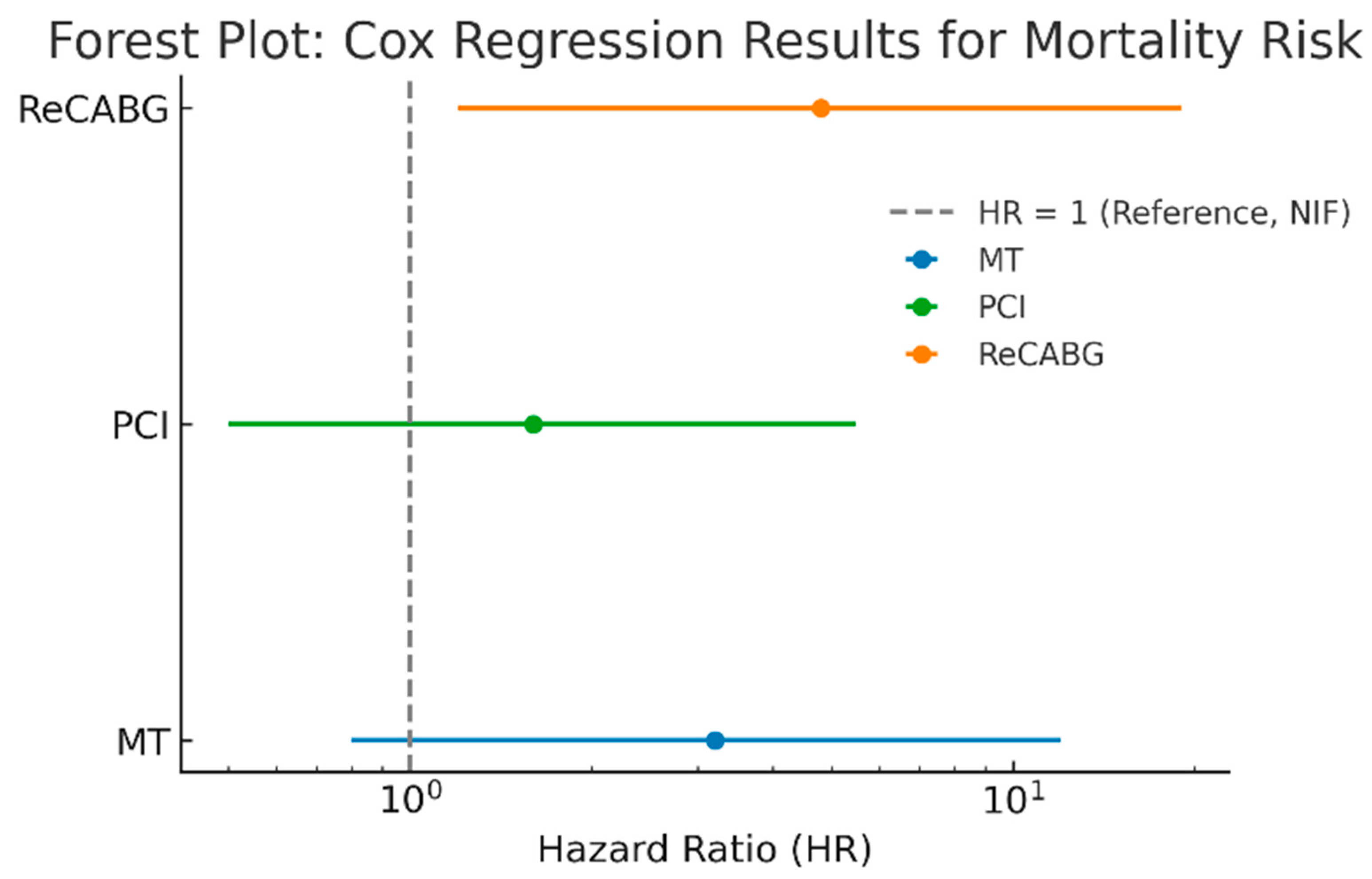

3.11. Multivariate Analysis

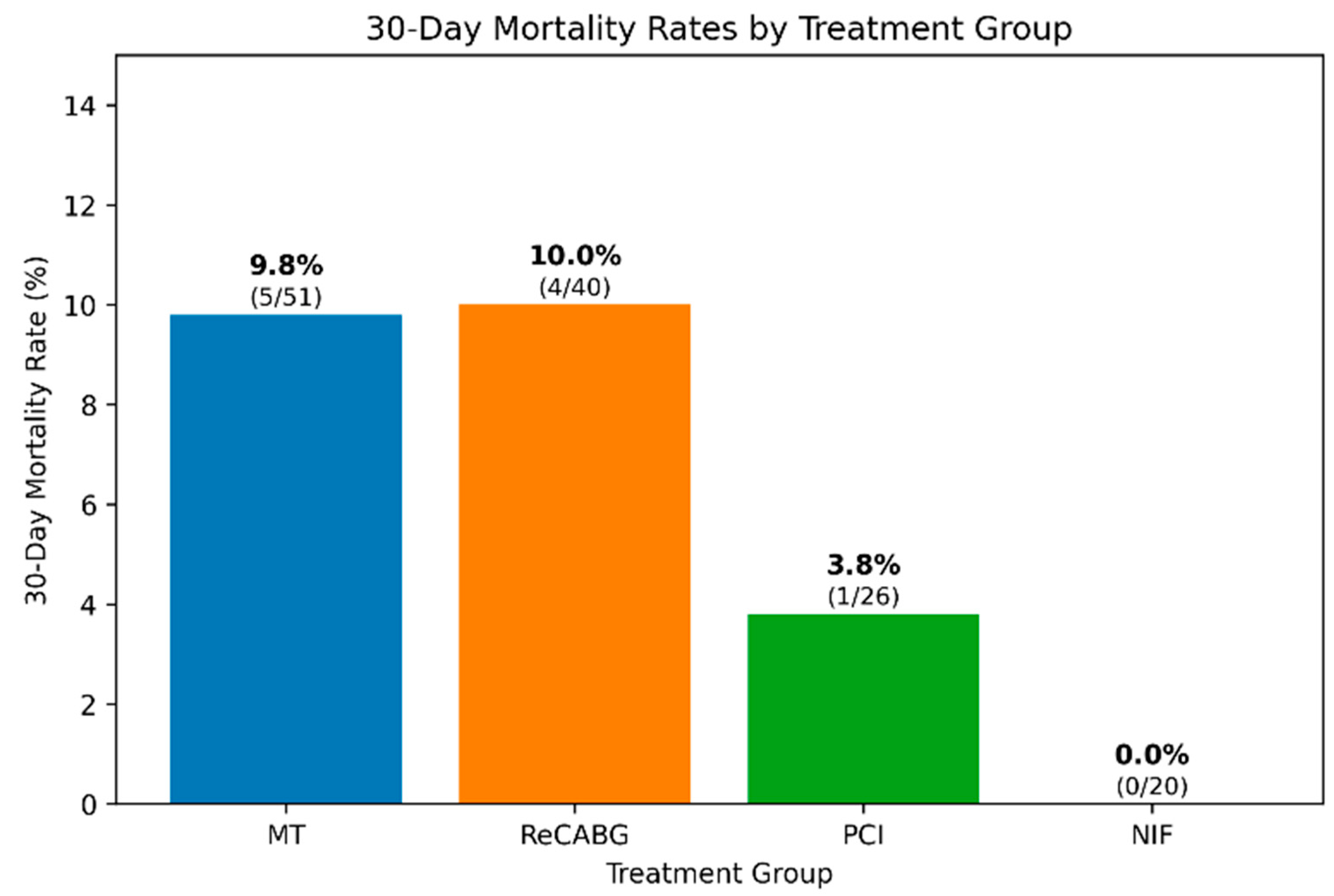

3.12. 30-Day Mortality Analysis

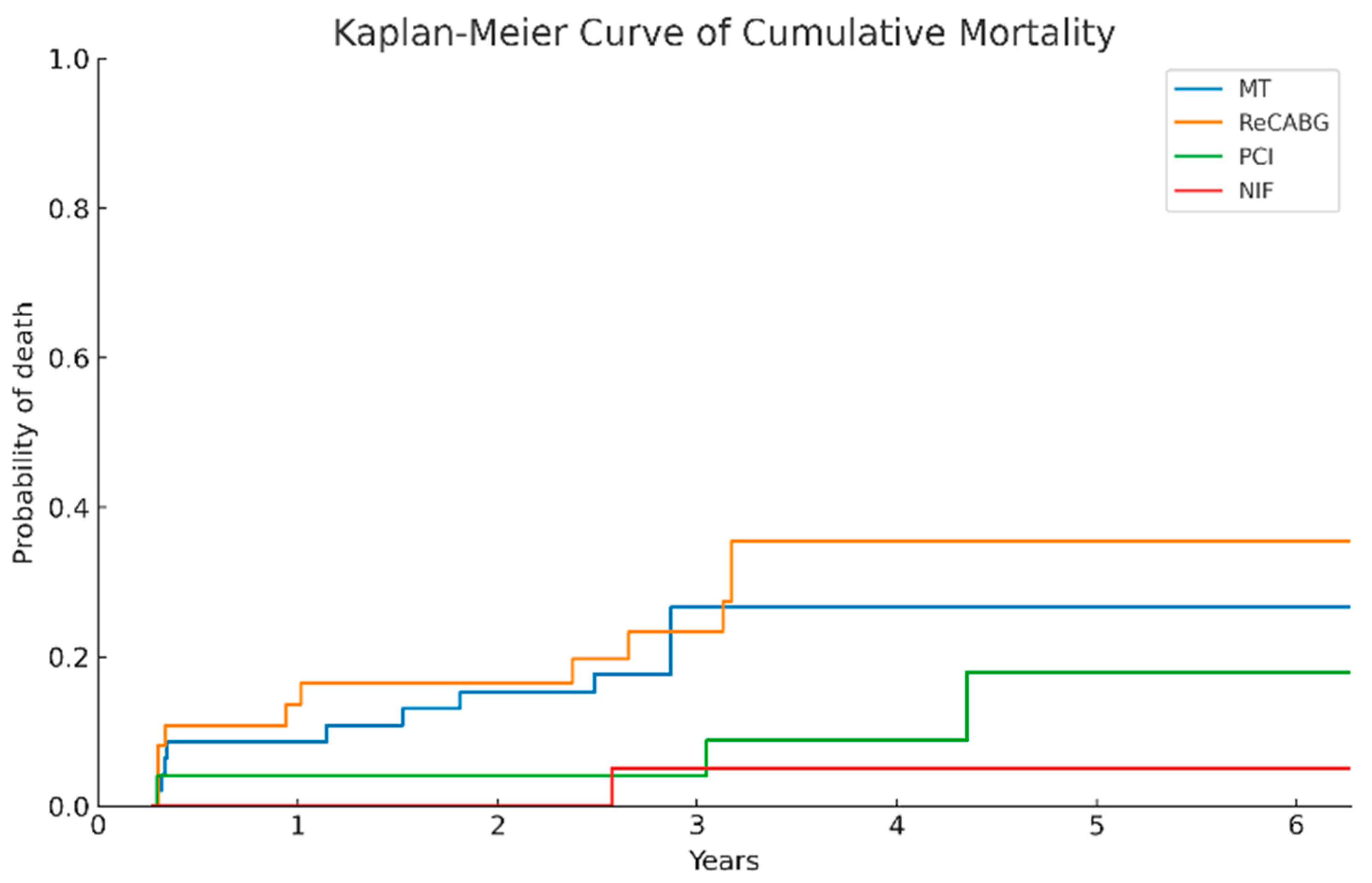

3.13. Comparison of Long-Term Survival Across Treatment Groups

3.14. Adverse Events of Repeat Coronary Angiography

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yau, J.M.; Alexander, J.H.; Hafley, G.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Mack, M.J.; Kouchoukos, N.; Goyal, A.; Peterson, E.D.; Gibson, C.M.; Califf, R.M.; et al. Impact of perioperative myocardial infarction on angiographic and clinical outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting (from project of ex-vivo vein graft engineering via transfection [prevent] iv). Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preusser, M.J.; Landwehrt, J.; Mastrobuoni, S.; Biancari, F.; Dakkak, A.R.; Alshakaki, M.; Martens, S.; Dell’Aquila, A.M. Survival results of postoperative coronary angiogram for treatment of perioperative myocardial ischaemia following coronary artery bypass grafting: A single-centre experience. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 26, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancari, F.; Anttila, V.; Dell’Aquila, A.M.; Airaksinen, J.K.E.; Brascia, D. Control angiography for perioperative myocardial ischemia after coronary surgery: Meta-analysis. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2018, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sef, D.; Szavits-Nossan, J.; Predrijevac, M.; Golubic, R.; Sipic, T.; Stambuk, K.; Korda, Z.; Meier, P.; Turina, M.I. Management of perioperative myocardial ischaemia after isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Open Heart 2019, 6, e001027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuts, S.; Gollmann-Tepekoylu, C.; Denessen, E.J.S.; Olsthoorn, J.R.; Romeo, J.L.R.; Maessen, J.G.; van ‘t Hof, A.W.J.; Bekers, O.; Hammarsten, O.; Polzl, L.; et al. Cardiac troponin release following coronary artery bypass grafting: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, M.; Sharma, V.; Al-Attar, N.; Bulluck, H.; Bisleri, G.; Bunge, J.J.H.; Czerny, M.; Ferdinandy, P.; Frey, U.H.; Heusch, G.; et al. Esc joint working groups on cardiovascular surgery and the cellular biology of the heart position paper: Perioperative myocardial injury and infarction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2392–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Jaffe, A.S.; Milojevic, M.; Sandoval, Y.; Devereaux, P.J.; Thygesen, K.; Myers, P.O.; Kluin, J. Great debate: Myocardial infarction after cardiac surgery must be redefined. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4170–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, J.S.; Jaffe, A.S.; Chaitman, B.R.; Bax, J.J.; Morrow, D.A.; White, H.D. Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/World Heart Federation Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial, Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2018, 138, e618–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, I.D.; Klein, L.W.; Shah, B.; Mehran, R.; Mack, M.J.; Brilakis, E.S.; Reilly, J.P.; Zoghbi, G.; Holper, E.; Stone, G.W. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: An expert consensus document from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions (scai). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, M.; Occhipinti, G.; Laudani, C.; Greco, A.; Capodanno, D. Periprocedural myocardial infarction and injury. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2024, 13, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.V.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Ruel, M.; Rab, T.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Alexander, J.H.; Baber, U.; Baker, H.; Cohen, M.G.; Cruz-Ruiz, M.; et al. 2025 acc/aha/acep/naemsp/scai guideline for the management of patients with acute coronary syndromes: A report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2025, 85, 2135–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 esc guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Flather, M.; Capodanno, D.; Milojevic, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Biondi Zoccai, G.; Boden, W.E.; Devereaux, P.J.; Doenst, T.; Farkouh, M.; et al. European association of cardio-thoracic surgery (eacts) expert consensus statement on perioperative myocardial infarction after cardiac surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2024, 65, ezad415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Dangas, G.D.; Angiolillo, D.J.; Brodt, J.; Chikwe, J.; DeAnda, A.; Hameed, I.; Rodgers, M.L.; Sandner, S.; Sun, L.Y.; et al. Considerations on the management of acute postoperative ischemia after cardiac surgery: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2023, 148, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, H.; Serruys, P.W.; Takahashi, K.; Kawashima, H.; Ono, M.; Gao, C.; Wang, R.; Mohr, F.W.; Holmes, D.R.; Davierwala, P.M.; et al. Impact of peri-procedural myocardial infarction on outcomes after revascularization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1622–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudino, M.; Di Franco, A.; Dimagli, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.; Rahouma, M.; Perezgrovas Olaria, R.; Soletti, G.; Cancelli, G.; Chadow, D.; Spertus, J.A.; et al. Correlation between periprocedural myocardial infarction, mortality, and quality of life in coronary revascularization trials: A meta-analysis. J. Soc. Cardiovasc. Angiogr. Interv. 2023, 2, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmvang, L.; Jurlander, B.; Rasmussen, C.; Thiis, J.J.; Grande, P.; Clemmensen, P. Use of biochemical markers of infarction for diagnosing perioperative myocardial infarction and early graft occlusion after coronary artery bypass surgery. Chest 2002, 121, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleissner, F.; Issam, I.; Martens, A.; Cebotari, S.; Haverich, A.; Shrestha, M.L. The unplanned postoperative coronary angiogram after cabg: Identifying the patients at risk. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2017, 65, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabricius, A.M.; Gerber, W.; Hanke, M.; Garbade, J.; Autschbach, R.; Mohr, F.W. Early angiographic control of perioperative ischemia after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2001, 19, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alter, P.; Vogt, S.; Herzum, M.; Irqsusi, M.; Rupp, H.; Maisch, B.; Moosdorf, R. Indications for angiography subsequent to coronary artery bypass grafting. Am. Heart J. 2005, 149, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielmann, M.; Massoudy, P.; Jaeger, B.R.; Neuhauser, M.; Marggraf, G.; Sack, S.; Erbel, R.; Jakob, H. Emergency re-revascularization with percutaneous coronary intervention, reoperation, or conservative treatment in patients with acute perioperative graft failure following coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2006, 30, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, M.; DeMey, N.; Bouchard, D.; Carrier, M.; Demers, P.; Pellerin, M.; Couture, P.; Perrault, L.P. Management of early postoperative coronary artery bypass graft failure. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2012, 14, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, L.; Schmid, C.; Debl, K.; Lunz, D.; Florchinger, B.; Keyser, A. Impact of coronary angiography early after cabg for suspected postoperative myocardial ischemia. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2019, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.; Thiis, J.J.; Clemmensen, P.; Efsen, F.; Arendrup, H.C.; Saunamaki, K.; Madsen, J.K.; Pettersson, G. Significance and management of early graft failure after coronary artery bypass grafting: Feasibility and results of acute angiography and re-re-vascularization. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1997, 12, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davierwala, P.M.; Verevkin, A.; Leontyev, S.; Misfeld, M.; Borger, M.A.; Mohr, F.W. Impact of expeditious management of perioperative myocardial ischemia in patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass surgery. Circulation 2013, 128, S226–S234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedjeholm, R.; Dahlin, L.G.; Lundberg, C.; Szabo, Z.; Kagedal, B.; Nylander, E.; Olin, C.; Rutberg, H. Are electrocardiographic q-wave criteria reliable for diagnosis of perioperative myocardial infarction after coronary surgery? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1998, 13, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Crescenzi, G.; Bove, T.; Pappalardo, F.; Scandroglio, A.M.; Landoni, G.; Aletti, G.; Zangrillo, A.; Alfieri, O. Clinical significance of a new q wave after cardiac surgery. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2004, 25, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, J.; Shernan, S.; Fitch, J.; Finnegan, P.; Todaro, T.; Filloon, T.; Nussmeier, N.A. Increased creatine kinase mb level predicts postoperative mortality after cardiac surgery independent of new q waves. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2005, 129, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carrier, M.; Pellerin, M.; Perrault, L.P.; Solymoss, B.C.; Pelletier, L.C. Troponin levels in patients with myocardial infarction after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2000, 69, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peivandi, A.A.; Dahm, M.; Opfermann, U.T.; Peetz, D.; Doerr, F.; Loos, A.; Oelert, H. Comparison of cardiac troponin i versus t and creatine kinase mb after coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with and without perioperative myocardial infarction. Herz 2004, 29, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armillotta, M.; Bergamaschi, L.; Paolisso, P.; Belmonte, M.; Angeli, F.; Sansonetti, A.; Stefanizzi, A.; Bertolini, D.; Bodega, F.; Amicone, S.; et al. Prognostic relevance of type 4a myocardial infarction and periprocedural myocardial injury in patients with non-st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2025, 151, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polzl, L.; Engler, C.; Sterzinger, P.; Lohmann, R.; Nagele, F.; Hirsch, J.; Graber, M.; Eder, J.; Reinstadler, S.; Sappler, N.; et al. Association of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin t with 30-day and 5-year mortality after cardiac surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereaux, P.J.; Lamy, A.; Chan, M.T.V.; Allard, R.V.; Lomivorotov, V.V.; Landoni, G.; Zheng, H.; Paparella, D.; McGillion, M.H.; Belley-Cote, E.P.; et al. High-sensitivity troponin i after cardiac surgery and 30-day mortality. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Overall Cohort n = 137 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 66.2 ± 8.8 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 99 (72.3) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27.3 ± 3.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 42 (30.7) |

| LVEF, mean ± SD | 56.5 ± 11.8 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 19 (13.9) |

| COPD, n (%) | 11 (8.0) |

| Renal insufficiency, n (%) | 18 (13.1) |

| PAOD, n (%) | 23 (16.8) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 29 (21.2) |

Coronary artery disease, n (%)

| 117 (85.4) 7 (5.1) 31 (22.6) 99 (72.3) |

| History of myocardial infarction, n (%) | 67 (48.9) |

| EuroSCORE II (%), mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 1.9 |

| Overall Cohort n = 137 | |

|---|---|

| Procedure time (min), mean ± SD | 162.0 ± 47.7 |

| CPBT (min), mean ± SD | 51.4 ± 17.3 |

| ACCT (min), mean ± SD | 41.7 ± 13.1 |

| Number of grafts, n (%) | 2.9 ± 0.7 |

| Number of anastomoses, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 0.9 |

| LIMA, n (%) | 128 (93.4) |

| RIMA, n (%) | 7 (5.1) |

| Overall Cohort n = 137 | |

|---|---|

| Pathologic angiographic findings, n (%) | 117 (85.4) |

| 4/117 (3.4) |

| 113/117 (96.6) |

| 76/117 (65) |

| 25/117 (21.4) |

| 12/117 (10.3) |

| 72/117 (61.5) |

| 36/72 (50) |

| 22/72 (30.6) |

| 14/72 (19.4) |

| 91/117 (77.8) |

| 55/91 (60.4) |

| 24/91 (26.4) |

| 12/91 (13.2) |

Angiographic findings needing re-intervention (PCI or CABG), n (%)

| 66 (47.4) 26 (19.0) 40 (29.2) |

| Pathologic angiographic findings treated conservatively, n (%) | 51 (37.2) |

| No pathologic angiographic findings, n (%) | 20 (14.6) |

| LIMA, n (%) | 128 (93.4) |

| RIMA, n (%) | 7 (5.1) |

| Overall Cohort n = 137 | |

|---|---|

| ECG changes | |

| 84 (61.3) |

| 27 (19.7) |

| 10 (7.5) |

| 14 (10.5) |

| Enzyme elevations | |

| 104 (78.2) |

| 94 (70.7) |

| 77 (57.9) |

| Overall Cohort n = 137 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathological Findings n = 117 | No Identified Finding n = 20 | p-Value | Univariate Analysis p-Value | Multivariate Analysis p-Value | |

| ECG changes | |||||

| 77 (65.8) | 7 (35.0) | 0.02 * | 0.01 * | <0.01 * |

| 37 (31.6) | 1 (5.0) | 0.01 * | 0.04 * | 0.02 * |

| 9 (7.7) | 1 (5.0) | >0.999 | >0.999 | 0.82 |

| 11 (9.4) | 3 (15.0) | 0.716 | 0.43 | 0.26 |

| Enzyme elevation | |||||

| 94 (80.3) | 10 (50.0) | <0.01 * | <0.01 * | 0.15 |

| 86 (73.5) | 8 (40.0) | <0.01 * | <0.01 * | 0.36 |

| 72 (61.5) | 5 (25.0) | <0.01 * | <0.01 * | 0.17 |

| Combination | |||||

| 68 (58.1) | 1 (5.0) | <0.01 * | <0.01 * | <0.001 * |

| 26 (22.2) | 2 (10.0) | 0.366 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| CK | ||||||

| Time course | Cut-off point | AUC | Sensitivity | 1-Specifity | LR+/LR− | p-value |

| Postoperative | 3.0 | 0.49 | 75.7% | 35.0% | 1.2/0.7 | 0.78 |

| 4 h | 24.4 | 0.49 | 20.5% | 0.0% | ∞ †/0.9 | 0.54 |

| 8 h | 10.1 | 0.79 | 89.2% | 73.3% | 3.2/0.2 | <0.01 * |

| 18 h | 10.9 | 0.77 | 92.1% | 68.7% | 2.9/0.2 | <0.01 * |

| CK-MB | ||||||

| Time course | Cut-off point | AUC | Sensitivity | 1-Specifity | LR+/LR− | p-value |

| Postoperative | 0.9 | 0.56 | 77.6% | 57.1% | 1.4/0.1 | 0.90 |

| 4 h | 1.6 | 0.57 | 20.5% | 100.0% | ∞ †/0.8 | 0.24 |

| 8 h | 0.7 | 0.83 | 89.2% | 73.3% | 3.3/0.1 | <0.01 * |

| 18 h | 0.5 | 0.81 | 92.1% | 67.7% | 2.8/0.2 | <0.01 * |

| CK/CK-MB ratio | ||||||

| Time course | Cut-off point | AUC | Sensitivity | 1-Specifity | LR+/LR− | p-value |

| Postoperative | 6.6 | 0.59 | 84.0% | 57.1% | 1.5/0.4 | 0.45 |

| 4 h | 6.6 | 0.61 | 69.2% | 40.0% | 1.7/0.5 | 0.27 |

| 8 h | 6.4 | 0.72 | 69.5% | 26.7% | 2.6/0.4 | 0.01 * |

| 18 h | 4.6 | 0.78 | 84.2% | 33.3% | 2.5/0.2 | <0.01 * |

| ∆CK18, ∆CK-MB18 | ||||||

| Time course | Cut-off point | AUC | Sensitivity | 1-Specifity | R+/LR− | p-value |

| ∆CK18 | 7.0 | 0.7 | 77.5% | 35.0% | 2.2/0.4 | <0.01 * |

| ∆CK-MB18 | 0.2 | 0.77 | 79.7% | 30.0% | 2.7/0.3 | <0.01 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taghizadeh-Waghefi, A.; Wilbring, M.; Petrov, A.; Arzt, S.; Kappert, U.; Tugtekin, S.-M.; Matschke, K.; Alexiou, K. Electrocardiogram-Alterations and Increasing Cardiac Enzymes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting—When Can We Expect Significant Findings in Coronary Angiography? Medicina 2025, 61, 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122192

Taghizadeh-Waghefi A, Wilbring M, Petrov A, Arzt S, Kappert U, Tugtekin S-M, Matschke K, Alexiou K. Electrocardiogram-Alterations and Increasing Cardiac Enzymes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting—When Can We Expect Significant Findings in Coronary Angiography? Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122192

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaghizadeh-Waghefi, Ali, Manuel Wilbring, Asen Petrov, Sebastian Arzt, Utz Kappert, Sems-Malte Tugtekin, Klaus Matschke, and Konstantin Alexiou. 2025. "Electrocardiogram-Alterations and Increasing Cardiac Enzymes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting—When Can We Expect Significant Findings in Coronary Angiography?" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122192

APA StyleTaghizadeh-Waghefi, A., Wilbring, M., Petrov, A., Arzt, S., Kappert, U., Tugtekin, S.-M., Matschke, K., & Alexiou, K. (2025). Electrocardiogram-Alterations and Increasing Cardiac Enzymes After Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting—When Can We Expect Significant Findings in Coronary Angiography? Medicina, 61(12), 2192. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122192