The Efficiency of Taurolidine Lock Solution in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Children with Intestinal Failure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Definition of CRBSI

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Catheter Characteristics and Outcomes

3.3. Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections

3.4. Adverse Events

4. Discussion

Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IF | Intestinal failure |

| PN | Parenteral nutrition |

| IT | Intestinal transplantation |

| CVC | Central venous catheter |

| CRBSI | Catheter-related bloodstream infection |

| TCS | Taurolidine and citrate solution |

| IFALD | Intestinal failure-associated liver disease |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| RR | Rate ratio |

References

- Diamanti, A.; Capriati, T.; Gandullia, P.; Di Leo, G.; Lezo, A.; Lacitignola, L.; Spagnuolo, M.I.; Gatti, S.; D’Antiga, L.; Verlato, G.; et al. Pediatric Chronic Intestinal Failure in Italy: Report from the 2016 Survey on Behalf of Italian Society for Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (SIGENP). Nutrients 2017, 9, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barclay, A.R.; Henderson, P.; Gowen, H.; Puntis, J.; BIFS collaborators. The continued rise of paediatric home parenteral nutrition use: Implications for service and the improvement of longitudinal data collection. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1128–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neelis, E.G.; Roskott, A.M.; Dijkstra, G.; Wanten, G.J.; Serlie, M.J.; Tabbers, M.M.; Damen, G.; Olthof, E.D.; Jonkers, C.F.; Kloeze, J.H.; et al. Presentation of a nationwide multicenter registry of intestinal failure and intestinal transplantation. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, E.; Yeo, K.T.; Wang, A.Y.; Callander, I.; Bajuk, B.; Bolisetty, S.; Lui, K.; NICUS Network. Dwell time and risk of central-line-associated bloodstream infection in neonates. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 97, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, R.E.; Bizzarro, M.J. Central line-associated bloodstream infections in the NICU: Successes and controversies in the quest for zero. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermel, L.A.; Allon, M.; Bouza, E.; Craven, D.E.; Flynn, P.; O’Grady, N.P.; Raad, I.I.; Rijnders, B.J.; Sherertz, R.J.; Warren, D.K. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1–45, Erratum in Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1079. Erratum in Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larson-Nath, C.; Wendt, L.; Rahhal, R. Catheter salvage from central line-related bloodstream infections in pediatric intestinal failure. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanks, R.M.; Donegan, N.P.; Graber, M.L.; Buckingham, S.E.; Zegans, M.E.; Cheung, A.L.; O’Toole, G.A. Heparin stimulates Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 4596–4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van de Wetering, M.D.; van Woensel, J.B. Prophylactic antibiotics for preventing early central venous catheter Gram positive infections in oncology patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, 1, CD003295, Erratum in Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 11, CD003295. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003295.pub3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, C.B.; Mittelman, M.W.; Costerton, J.W.; Parenteau, S.; Pelak, M.; Arsenault, R.; Mermel, L.A. Antimicrobial activity of a novel catheter lock solution. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 1674–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reidenberg, B.E.; Wanner, C.; Polsky, B.; Castanheira, M.; Shelip, A.; Stalleicken, D.; Pfaffle, A.E. Postmarketing experience with Neutrolin® (taurolidine, heparin, calcium citrate) catheter lock solution in hemodialysis patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 661–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Torres-Viera, C.; Thauvin-Eliopoulos, C.; Souli, M.; DeGirolami, P.; Farris, M.G.; Wennersten, C.B.; Sofia, R.D.; Eliopoulos, G.M. Activities of taurolidine in vitro and in experimental enterococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1720–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Silva, T.N.; Mendes, M.L.; Abrão, J.M.; Caramori, J.T.; Ponce, D. Successful prevention of tunneled central catheter infection by antibiotic lock therapy using cefazolin and gentamicin. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2013, 45, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wan, G.; Liang, L. Taurolidine lock solution for catheter-related bloodstream infections in pediatric patients: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Núñez-Ramos, R.; Germán Díaz, M.; Moreno Villares, J.M.; Polo Miquel, B.; Salazar Quero, J.C.; Cabello Ruiz, V.; Redecillas Ferreiro, S.; Ramos Boluda, E. Taurolidine lock in pediatric patients with intestinal failure. A practical guideline from the Spanish Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (SEGHNP). Nutr. Hosp. 2024, 41, 702–705. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribler, S.; Brandt, C.F.; Petersen, A.H.; Petersen, J.H.; Fuglsang, K.A.; Staun, M.; Broebech, P.; Moser, C.E.; Jeppesen, P.B. Taurolidine-citrate-heparin lock reduces catheter-related bloodstream infections in intestinal failure patients dependent on home parenteral support: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, Y.; Theilla, M.; Singer, P.; Tribler, S.; Jeppesen, P.B.; Pironi, L.; Vinter-Jensen, L.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Rahman, F.; Wanten, G.J.A. Randomised clinical trial: 2% taurolidine versus 0.9% saline locking in patients on home parenteral nutrition. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chong, C.Y.; Ong, R.Y.; Seah, V.X.; Tan, N.W.; Chan, M.Y.; Soh, S.Y.; Ong, C.; Lim, A.S.; Thoon, K.C. Taurolidine-citrate lock solution for the prevention of central line-associated bloodstream infection in paediatric haematology-oncology and gastrointestinal failure patients with high baseline central-line associated bloodstream infection rates. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 56, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerstrøm, C.T.; Scheike, T.; Moser, C.E.; Tribler, S.; Jeppesen, P.B. Taurolidine lock reduces recurrent catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients with chronic intestinal failure: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial in a real-world clinical setting. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 51, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.Q.; Cao, L.; Xia, H.T.; Ma, J.J. Taurolidine lock solutions for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alfieri, A.; Di Franco, S.; Passavanti, M.B.; Pace, M.C.; Simeon, V.; Chiodini, P.; Leone, S.; Fiore, M. Antimicrobial Lock Therapy in Clinical Practice: A Scoping Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van den Bosch, C.H.; Jeremiasse, B.; van der Bruggen, J.T.; Frakking, F.N.J.; Loeffen, Y.G.T.; van de Ven, C.P.; van der Steeg, A.F.W.; Fiocco, M.F.; van de Wetering, M.D.; Wijnen, M.H.W.A. The efficacy of taurolidine containing lock solutions for the prevention of central-venous-catheter-related bloodstream infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 123, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mank, E.; Broos, N.; Terreehorst, I.; Liem, O.; Nusman, C.M.; Gerards, A.E.; Derikx, J.P.M.; Tabbers, M.M. TauroSept-Induced Anaphylaxis: A Pediatric Case Report. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2025, 38, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.J.; Moy, N.; Kaazan, P.; Callaghan, G.; Holtmann, G.; Martin, N. Cost-effectiveness of taurolidine-citrate in a cohort of patients with intestinal failure receiving home parenteral nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2024, 48, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, G.; Ben-Shimol, S.; Elamour, S.; Nassar, R.; Kristal, E.; Shalev, R.; Howard, G.; Yerushalmi, B.; Kogan, S.; Shmueli, M. The Effectiveness of Taurolidine Antimicrobial Locks in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections (CRBSI) in Children Receiving Parenteral Nutrition: A Case Series. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Total | TCS | Heparinized Saline | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics, n (%) | 48 (100) | 25 (52.0) | 23 (48.0) | - |

| Sex (Female), n (%) | 26 (54.2) | 16 (64.0) | 10 (43.5) | 0.246 a |

| Age at baseline, months median (IQR) | 7.7 (4–17.5) | 8.5 (5–16) | 6 (2.7–20) | 0.183 b |

| Follow-up period, months median (IQR) | 7.2 (2.6–14) | 7 (2–14) | 7.5 (3–18) | 0.810 b |

| Diagnosis classification, n (%) | 0.138 a | |||

| Short bowel syndrome | 27 (56.3) | 11 (44.0) | 16 (69.6) | |

| Intestinal dysmotility | 12 (25.0) | 7 (28.0) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Congenital diarrhea | 9 (18.7) | 7 (28.0) | 2 (8.7) | |

| Patients with an ostomy, n (%) | 29 (60.4) | 12 (48.0) | 13 (56.5) | 0.083 a |

| Intestinal transplantation, n (%) | 10 (20.8) | 2 (8.0) | 8 (34.7) | - |

| IFALD, n (%) | 4 (8.3) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (13.0) | - |

| Home PN, n (%) | 4 (8.3) | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.3) | - |

| Weaning off PN, n (%) | 11(22.9) | 4 (16.0) | 7 (30.4) | - |

| Total | TCS | Heparinized Saline | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Catheter Duration, days median (IQR) | 135 (60–300) | 90 (60–330) | 165 (60–412.5) | 0.960 b |

| CVC removals due to any reason/1000 catheter days, median (IQR) | 13.3 (8.3–33.3) | 13.6 (7.9–33.3) | 12.1 (8.7–33.3) | 0.305 b |

| Type of CVC, n (%) | 0.137 a | |||

| Nontunneled CVC | 15 (31.3) | 11 (44) | 4 (17.4) | |

| Implantable port | 17 (35.4) | 7 (28) | 10 (43.5) | |

| Both | 16 (33.3) | 7 (28) | 9 (39.1) | |

| CRBSI/1000 catheter Days, median (IQR) | 33.3 (8.6–53.1) | 33.3 (11.1–39.3) | 36.3 (3.0–83.3) | 0.383 b |

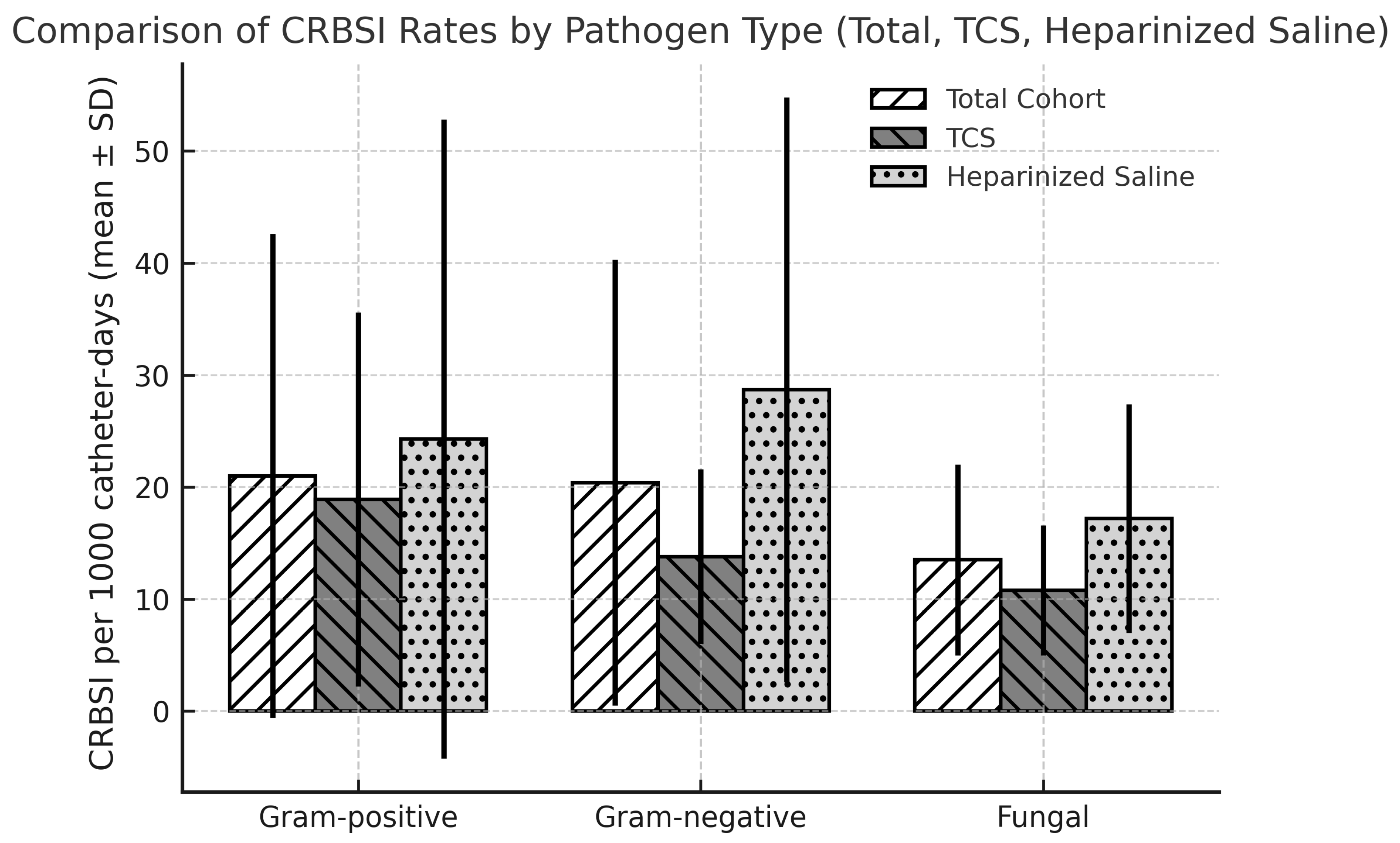

| The organism of CRBSI/1000 catheter days, median (IQR) | ||||

| Gram-positive | 13.3 (5.0–33.3) | 12.8 (5.2–33.3) | 13.3 (3.7–37.8) | 0.877 b |

| Gram-negative | 16.6 (11.1–22.9) | 12.6 (11.1–16.6) | 19.9 (13.1–37.0) | 0.022 b |

| Fungal species | 12.1 (7.5–18.1) | 11.1 (4.1–14.0) | 13.9 (11.1–25.3) | 0.037 b |

| CRBSI | RR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.78 | 0.70–0.87 | <0.001 |

| Gram-positive | 0.78 | 0.65–0.93 | 0.006 |

| Gram-negative | 0.48 | 0.41–0.57 | <0.001 |

| Fungal species | 0.63 | 0.52–0.77 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aksoy, B.; Onbaşı Karabağ, Ş.; Çağan Appak, Y.; Güler, S.; Kahveci, S.; Yılmaz, D.; Baran, M. The Efficiency of Taurolidine Lock Solution in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Children with Intestinal Failure. Medicina 2025, 61, 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122188

Aksoy B, Onbaşı Karabağ Ş, Çağan Appak Y, Güler S, Kahveci S, Yılmaz D, Baran M. The Efficiency of Taurolidine Lock Solution in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Children with Intestinal Failure. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122188

Chicago/Turabian StyleAksoy, Betül, Şenay Onbaşı Karabağ, Yeliz Çağan Appak, Selen Güler, Sinem Kahveci, Dilek Yılmaz, and Maşallah Baran. 2025. "The Efficiency of Taurolidine Lock Solution in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Children with Intestinal Failure" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122188

APA StyleAksoy, B., Onbaşı Karabağ, Ş., Çağan Appak, Y., Güler, S., Kahveci, S., Yılmaz, D., & Baran, M. (2025). The Efficiency of Taurolidine Lock Solution in Preventing Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Children with Intestinal Failure. Medicina, 61(12), 2188. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122188