A Nationwide Analysis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intracranial Injuries: No Impact on Mortality but Prolonged Hospital Stays in Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Outcome and Covariables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

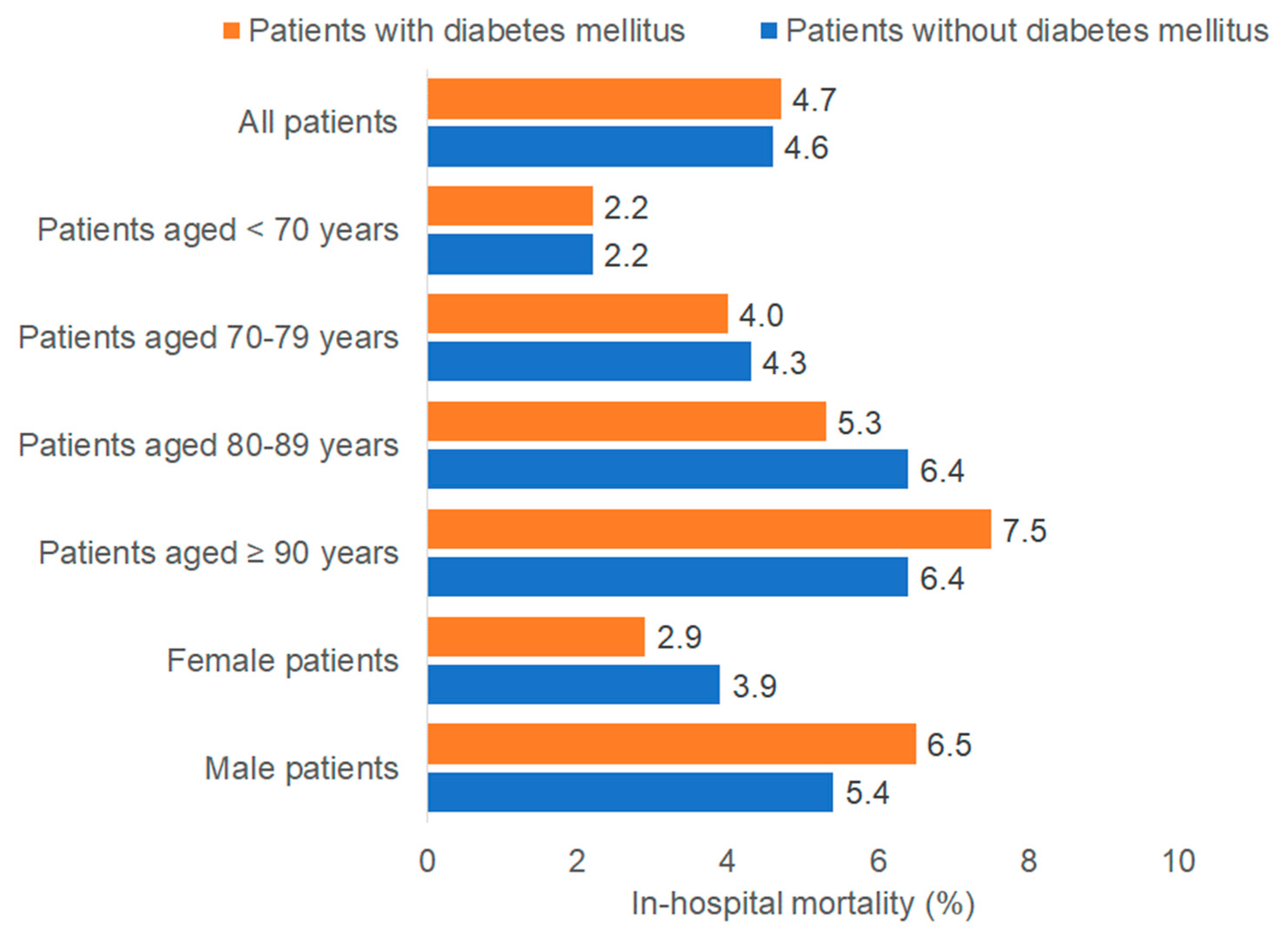

3.2. Association Between Diabetes and In-Hospital Mortality

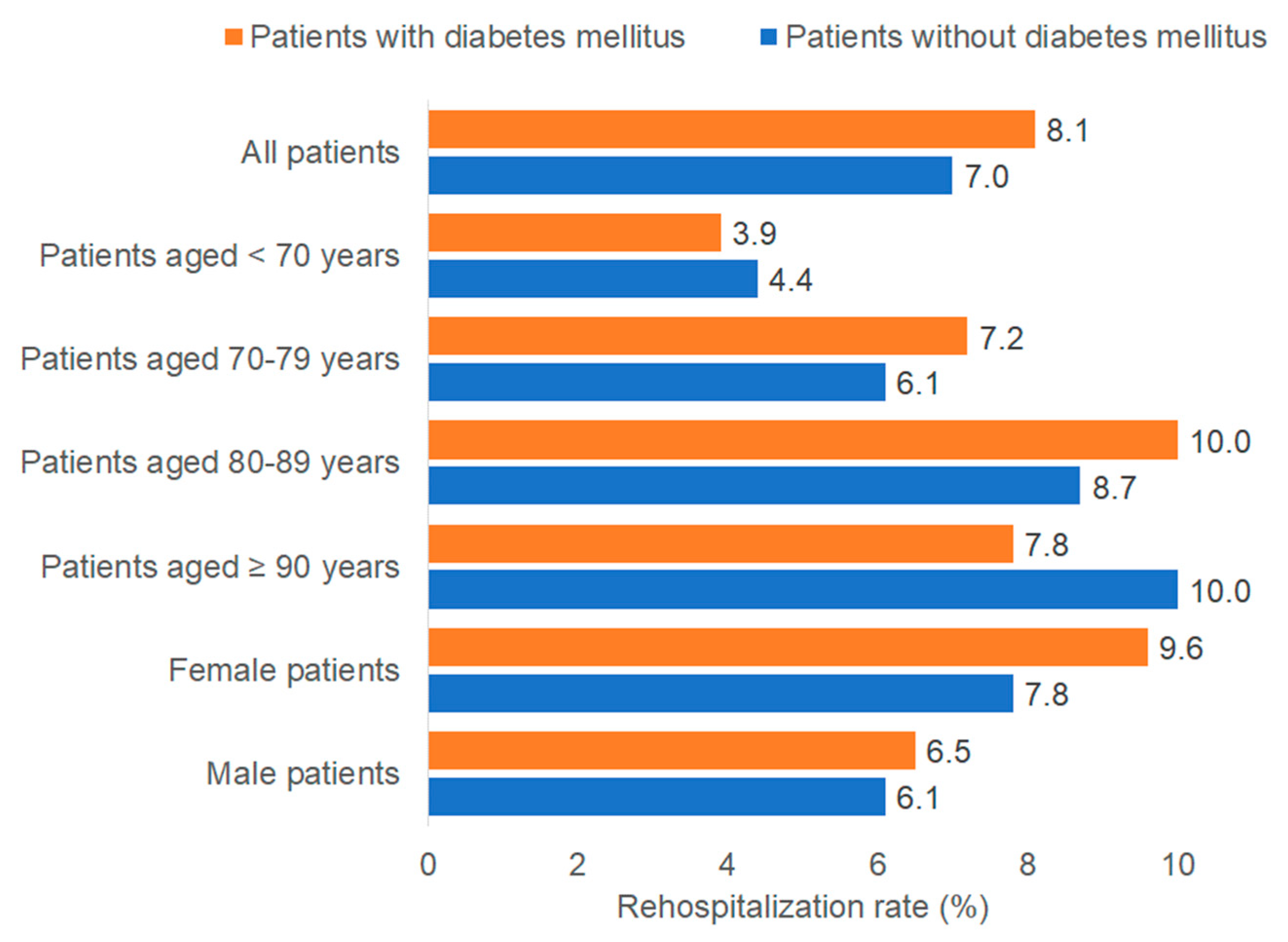

3.3. Association Between Diabetes and Rehospitalization Rate

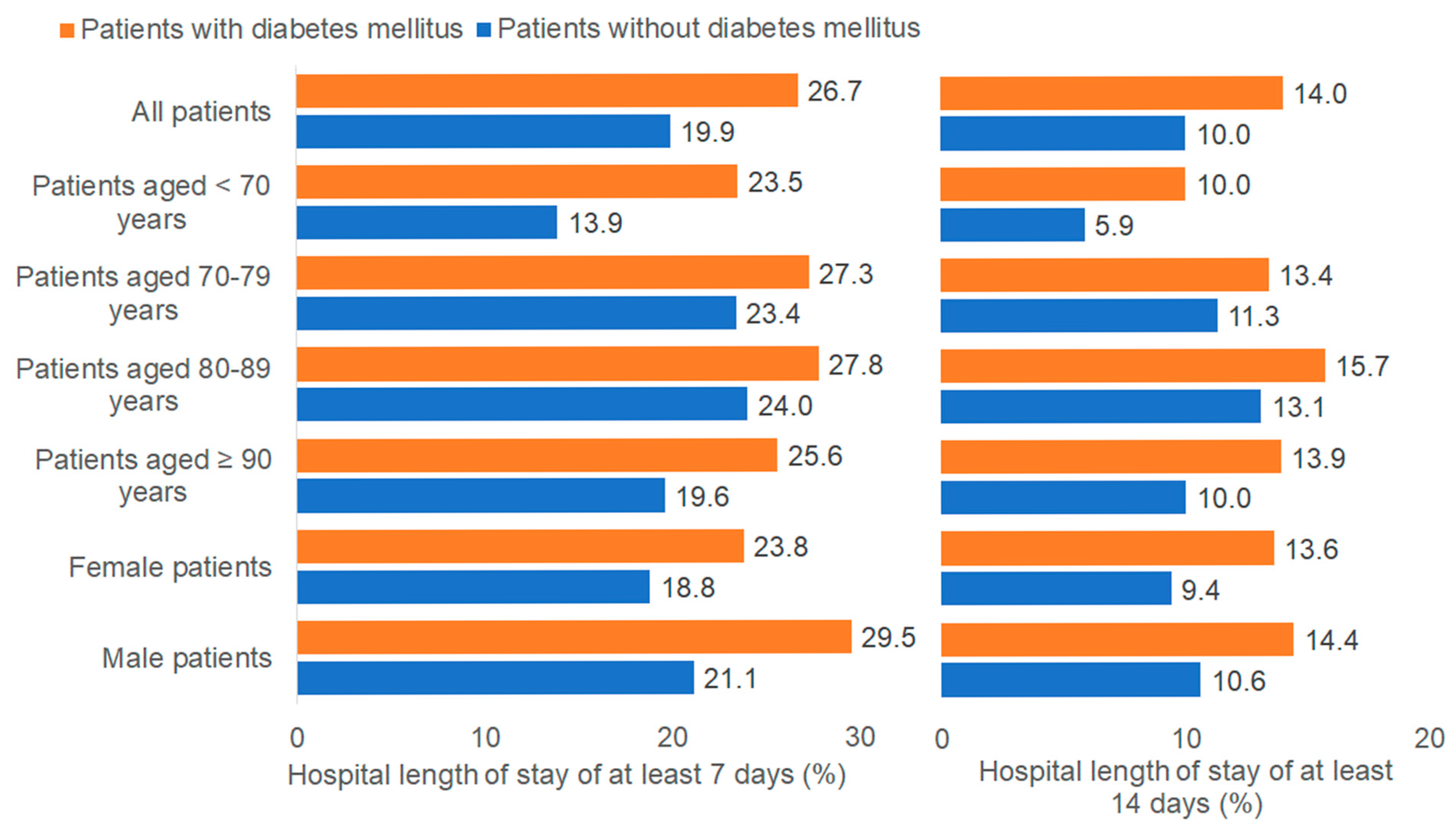

3.4. Association Between Diabetes and Hospital Length of Stay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Pratt, A.; Owens, A.; Barron, E.; Dunbar-Rees, R.; Slade, E.T.; Hafezparast, N.; Bakhai, C.; Chappell, P.; Cornelius, V.; et al. The burden of diabetes-associated multiple long-term conditions on years of life spent and lost. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigland, T.; Igland, J.; Tell, G.S.; Haltbakk, J.; Graue, M.; Fismen, A.S.; Birkeland, K.I.; Østbye, T.; Peyrot, M.; Iversen, M.M. The prevalence and incidence of pharmacologically treated diabetes among older people receiving home care services in Norway 2009–2014: A nationwide longitudinal study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 159. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, L.B.; Brasil-Neto, J.P.; da Silva, M.L.; Miranda, M.G.C.; Cruz, L.d.M.; Martins, W.R.; Paz, L.P.d.S. Risk factors for falls in older adults with diabetes mellitus: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jürgens, L.; Sarabhai, T.; Kostev, K. In-Hospital Mortality Among Elderly Patients Hospitalized for Femur Fracture with and Without Diabetes Mellitus: A Multicenter Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, S.A. Brain injury with diabetes mellitus: Evidence, mechanisms and treatment implications. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 10, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowery, N.T.; Gunter, O.L.; Guillamondegui, O.; Dossett, L.A.; Dortch, M.J.; Morris, J.A., Jr.; May, A.K. Stress insulin resistance is a marker for mortality in traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma 2009, 66, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, E.J.; Srour, M.K.; Clond, M.A.; Barnajian, M.; Tillou, A.; Mirocha, J.; Salim, A. Diabetic patients with traumatic brain injury: Insulin deficiency is associated with increased mortality. J. Trauma 2011, 70, 1141–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, D.Z.; Singer, M.B.; Barmparas, G.; Harada, M.Y.; Mirocha, J.; Bukur, M.; Salim, A.; Ley, E.J. Insulin-dependent diabetes and serious trauma. Eur. J. Trauma Emerg. Surg. 2016, 42, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-C.; Huang, Y.-C.; Tu, P.-H.; Yip, P.-K.; Chang, T.-W.; Lee, C.-C.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, N.-Y.; Liu, Z.-H. Impact of Diabetic Hyperglycemia on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Turk. Neurosurg. 2023, 33, 548–555. [Google Scholar]

- van Sloten, T.T.; Sedaghat, S.; Carnethon, M.R.; Launer, L.J.; A Stehouwer, C.D. Cerebral microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes: Stroke, cognitive dysfunction, and depression. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostev, K.; Laduch, O.; Scheimann, S.; Konrad, M.; Bohlken, J.; Luedde, M. Mortality rate and factors associated with in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized with pulmonary embolism in Germany. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2024, 57, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostev, K.; Michalowsky, B.; Bohlken, J. In-Hospital Mortality in Patients with and without Dementia across Age Groups, Clinical Departments, and Primary Admission Diagnoses. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.; Ott, L.; Dempsey, R.; Haack, D.; Tibbs, P. Relationship between admission hyperglycemia and neurologic outcome of severely brain-injured patients. Ann. Surg. 1989, 210, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-C.; Wu, S.-C.; Hsieh, T.-M.; Liu, H.-T.; Huang, C.-Y.; Chou, S.-E.; Su, W.-T.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H. Association of Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia and Diabetic Hyperglycemia with Mortality in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: Analysis of a Propensity Score-Matched Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Dong, B.; Mao, Y.; Guan, W.; Cao, J.; Zhu, R.; Wang, S. Review: Traumatic brain injury and hyperglycemia, a potentially modifiable risk factor. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 71052–71061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, L.; Iscra, F.; Ganau, M.; Berlot, G. Early predictive factors on mortality in head injured patients: A retrospective analysis of 112 traumatic brain injured patients. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2012, 56, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rau, C.-S.; Wu, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chien, P.-C.; Hsieh, H.-Y.; Kuo, P.-J.; Hsieh, C.-H. Stress-Induced Hyperglycemia, but Not Diabetic Hyperglycemia, Is Associated with Higher Mortality in Patients with Isolated Moderate and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Analysis of a Propensity Score-Matched Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosarge, P.L.; Shoultz, T.H.; Griffin, R.L.; Kerby, J.D. Stress-induced hyperglycemia is associated with higher mortality in severe traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 79, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovlias, A.; Kotsou, S. The influence of hyperglycemia on neurological outcome in patients with severe head injury. Neurosurgery 2000, 46, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremitsky, E.; Omert, L.A.; Dunham, C.M.; Wilberger, J.; Rodriguez, A. The impact of hyperglycemia on patients with severe brain injury. J. Trauma 2005, 58, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teigland, T.; Igland, J.; Graue, M.; Blytt, K.M.; Haltbakk, J.; Tell, G.S.; Birkeland, K.I.; Østbye, T.; Kirkevold, M.; Iversen, M.M. Associations between diabetes and risk of short-term and long-term nursing home stays among older people receiving home care services: A nationwide registry study. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozioł, M.; Towpik, I.; Żurek, M.; Niemczynowicz, J.; Wasążnik, M.; Sanchak, Y.; Wierzba, W.; Franek, E.; Walicka, M. Predictors of Rehospitalization and Mortality in Diabetes-Related Hospital Admissions. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubens, M.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Saxena, A.; McGranaghan, P.; McCormack-Granja, E. Recent Trends in Diabetes-Associated Hospitalizations in the United States. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifu, D.X.; Kreutzer, J.S.; Marwitz, J.H.; Miller, M.; Hsu, G.M.; Seel, R.T.; Englander, J.; High, W.M.; Zafonte, R. Etiology and incidence of rehospitalization after traumatic brain injury: A multicenter analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1999, 80, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.; Frisbie, J.; Wasfie, T.; Boyer, J.J.; Knisely, T.; Cwalina, N.; Barber, K.; Shapiro, B. A retrospective analysis of factors influencing readmission rates of acute traumatic subdural hematoma in the elderly: A cohort study. Int. J. Surg. Open 2019, 20, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.K.; Krishnan, N.; Chyall, L.; Haddad, A.F.; Vega, P.; Caldwell, D.J.; Umbach, G.; Tantry, E.; Tarapore, P.E.; Huang, M.C.; et al. Predictors of Extreme Hospital Length of Stay After Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg. 2022, 167, e998–e1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, G.A.; Lianos, G.; Fotakopoulos, G.; Michos, E.; Pachatouridis, D.; Voulgaris, S. Admission glucose and coagulopathy occurrence in patients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2014, 28, 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; He, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Kang, X.; Fu, G.; Xie, F.; Li, A.; Chen, J.; Wang, W. Association between blood glucose levels and Glasgow Outcome Score in patients with traumatic brain injury: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Trials 2022, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleke, B.E.; Salim, A.; Morton, J.I.; Gabbe, B.J.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E. Excess Risk of Injury in Individuals with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes Compared with the General Population. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (n = 2394) | Patients Without Diabetes Mellitus (n = 10,326) | p Value * | Standardized Mean Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Median age (IQR)) | 82 (12) | 79 (23) | <0.001 | 0.375 |

| <70 years, n (%) | 409 (17.1) | 3457 (33.5) | <0.001 | −0.384 |

| 70–79 years, n (%) | 545 (22.8) | 1838 (17.8) | 0.125 | |

| 80–89 years, n (%) | 1159 (48.4) | 3706 (35.9) | 0.255 | |

| ≥90 years, n (%) | 281 (11.7) | 1325 (12.8) | −0.034 | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 1184 (49.5) | 5350 (51.8) | 0.038 | −0.046 |

| Male | 1210 (50.5) | 4976 (48.2) | 0.046 | |

| Hospitalization year, n (%) | ||||

| 2019 | 190 (7.9) | 842 (8.2) | −0.011 | |

| 2020 | 365 (15.3) | 1594 (15.4) | −0.003 | |

| 2021 | 536 (22.4) | 2275 (22.0) | 0.465 | 0.010 |

| 2022 | 609 (25.4) | 2468 (23.9) | 0.035 | |

| 2023 | 694 (29.0) | 3147 (30.5) | −0.033 | |

| Co-diagnoses, n (%) | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 601 (25.1) | 1239 (12.0) | <0.001 | 0.383 |

| Hypertension | 1803 (75.3) | 5112 (49.5) | <0.001 | 0.553 |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 519 (21.7) | 955 (9.3) | <0.001 | 0.348 |

| Heart failure | 311 (13.0) | 620 (6.0) | <0.001 | 0.240 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 464 (19.4) | 709 (6.9) | <0.001 | 0.376 |

| All-cause-dementia | 527 (22.0) | 1618 (15.7) | <0.001 | 0.161 |

| Alcohol related disorders | 112 (4.7) | 935 (9.1) | <0.001 | −0.174 |

| Variables | In-Hospital Mortality | Rehospitalization Due to Intracranial Injury | In-Hospital Length of Stay of at Least 7 Days | In-Hospital Length of Stay of at Least 14 Days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Total | 0.98 (0.78–1.22) | 0.849 | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 0.526 | 1.13 (1.01–1.26) | 0.028 | 1.09 (0.95–1.25) | 0.245 |

| <70 years | 0.87 (0.41–1.85) | 0.714 | 0.69 (0.40–1.21) | 0.194 | 1.25 (0.95–1.64) | 0.106 | 0.97 (0.66–2.43) | 0.892 |

| 70–79 years | 1.08 (0.64–1.83) | 0.769 | 1.21 (0.81–1.81) | 0.353 | 1.00 (0.80–1.27) | 0.973 | 0.96 (0.70–1.30) | 0.775 |

| 80–89 years | 0.84 (0.62–1.15) | 0.277 | 1.20 (0.95–1.52) | 0.118 | 1.03 (0.88–1.21) | 0.705 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.819 |

| ≥90 years | 1.29 (0.76–2.18) | 0.345 | 0.69 (0.43–1.12) | 0.138 | 1.29 (0.94–1.76) | 0.115 | 1.27 (0.86–1.89) | 0.236 |

| Female | 0.75 (0.51–1.11) | 0.149 | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) | 0.182 | 1.07 (0.91–1.26) | 0.399 | 1.14 (093–1.39) | 0.210 |

| Male | 1.14 (0.87–1.51) | 0.347 | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 0.581 | 1.19 (1.02–1.38) | 0.026 | 1.04 (0.86–1.27) | 0.670 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarabhai, T.; Jürgens, L.; Kostev, K. A Nationwide Analysis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intracranial Injuries: No Impact on Mortality but Prolonged Hospital Stays in Germany. Medicina 2025, 61, 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122187

Sarabhai T, Jürgens L, Kostev K. A Nationwide Analysis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intracranial Injuries: No Impact on Mortality but Prolonged Hospital Stays in Germany. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122187

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarabhai, Theresia, Lavinia Jürgens, and Karel Kostev. 2025. "A Nationwide Analysis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intracranial Injuries: No Impact on Mortality but Prolonged Hospital Stays in Germany" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122187

APA StyleSarabhai, T., Jürgens, L., & Kostev, K. (2025). A Nationwide Analysis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intracranial Injuries: No Impact on Mortality but Prolonged Hospital Stays in Germany. Medicina, 61(12), 2187. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122187