1. Introduction

Endometrial cancer is one of the most common gynecological malignancies in women worldwide, and its incidence continues to rise, particularly in developed countries [

1]. Although early-stage disease generally has a favorable prognosis, recurrence and resistance to chemotherapy in advanced stages present major clinical challenges, significantly limiting long-term survival [

2]. This underscores the urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches that can overcome treatment resistance and improve outcomes.

GEM, a nucleoside analog that interferes with DNA synthesis, is widely used as an effective chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of solid tumors [

3]. However, its clinical efficacy is often limited due to intrinsic and acquired resistance, as well as dose-dependent toxicities, which restrict its use as monotherapy [

4]. As a result, combination therapies are preferred to improve treatment response. In this context, the integration of natural compounds with conventional chemotherapeutics has emerged as a promising strategy to suppress tumor progression while potentially reducing side effects [

5].

BA, a pentacyclic triterpene derived from

Boswellia serrata resin, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [

6]. Preclinical evidence indicates that BA sensitizes gastric cancer cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis via p53 signaling [

7] and modulates angiogenesis and survival pathways in other malignancies [

8]. These multimodal activities highlight its potential as an adjuvant compound in cancer therapy.

Hypoxia and angiogenesis are recognized as critical hallmarks of endometrial cancer progression. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a key regulator of cellular adaptation to low-oxygen conditions, while vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR2 drive tumor vascularization and correlate with poor prognosis [

9]. Hypoxia is highly prevalent in endometrial carcinomas and represents a critical driver of tumor progression, angiogenesis, and therapeutic resistance. Clinical and histopathological analyses have demonstrated that hypoxic endometrial tumors with increased vascular density are significantly associated with poorer disease-specific and distant disease-free survival, emphasizing the prognostic impact of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis [

10]. Furthermore, recent findings indicate that a higher proportion of HIF-1α–positive immune cells correlates with higher histologic grade and diffuse GLUT-1 expression patterns in endometrial cancer, suggesting that hypoxia-regulated proteins contribute to tumor aggressiveness and may serve as potential prognostic biomarkers [

11]. Collectively, these data highlight the biological and clinical importance of targeting hypoxia-driven molecular mechanisms in endometrial cancer. Targeting these pathways is therefore considered a rational approach to enhance therapeutic efficacy.

Based on these considerations, the present study investigated the effects of BA and GEM, individually and in combination, on key molecular pathways driving endometrial cancer progression. Unlike our previous investigations involving flavonoid-based compounds such as hesperidin in combination with chemotherapeutics, this study introduces BA (a pentacyclic triterpenoid) as a structurally and mechanistically distinct natural agent. Furthermore, the experiments were performed under hypoxic conditions (1% O2) to closely mimic the tumor microenvironment and to explore the modulation of HIF-1α/VEGF signaling, which was not evaluated in our earlier normoxic studies.

The use of ECC-1 endometrial carcinoma cells, representing a different molecular subtype from models such as ISHIKAWA, also provides additional insight into tumor heterogeneity and response variability. Collectively, this study provides the first demonstration that BA synergizes with GEM to suppress hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and promote apoptosis in endometrial cancer cells, highlighting its novel contribution beyond previously reported flavonoid-based synergistic models.

2. Material and Methods

The assays selected in this study were chosen to comprehensively evaluate the effects of BA and GEM on key molecular pathways implicated in hypoxia-driven angiogenesis and apoptosis. MTT and cell-cycle analyses were used to assess proliferation and cytotoxicity; VEGF ELISA and HIF-1α/HIF-dependent markers were used to examine hypoxia-induced angiogenesis; caspase activity, Bax/Bcl-2, and Annexin V assays assessed apoptosis activation through intrinsic and extrinsic pathways; cytokine profiling evaluated inflammatory modulation; and GO enrichment analysis was performed to identify integrated biological pathways modulated by BA and GEM.

2.1. Cell Culture and Maintenance of ECC-1 Endometrial Cancer Cells

The human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line (ECC-1; CRL-2923, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was cultured under standard conditions. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

The ECC-1 human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line (CRL-2923, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) was authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling prior to experiments and routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were used within passages 3–10 to ensure genomic stability.

2.2. Preparation and Application of BA and GEM

BA (BA; 3-O-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to prepare a stock solution and further diluted with culture medium to the desired concentrations. The final concentration of DMSO in culture medium did not exceed 0.1%. GEM (GEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in sterile distilled water prior to use. Cells were divided into single-agent treatment groups (BA or GEM) and a combination group (BA + GEM) and were incubated for 24 h and 48 h. Control cells received only the corresponding solvent.

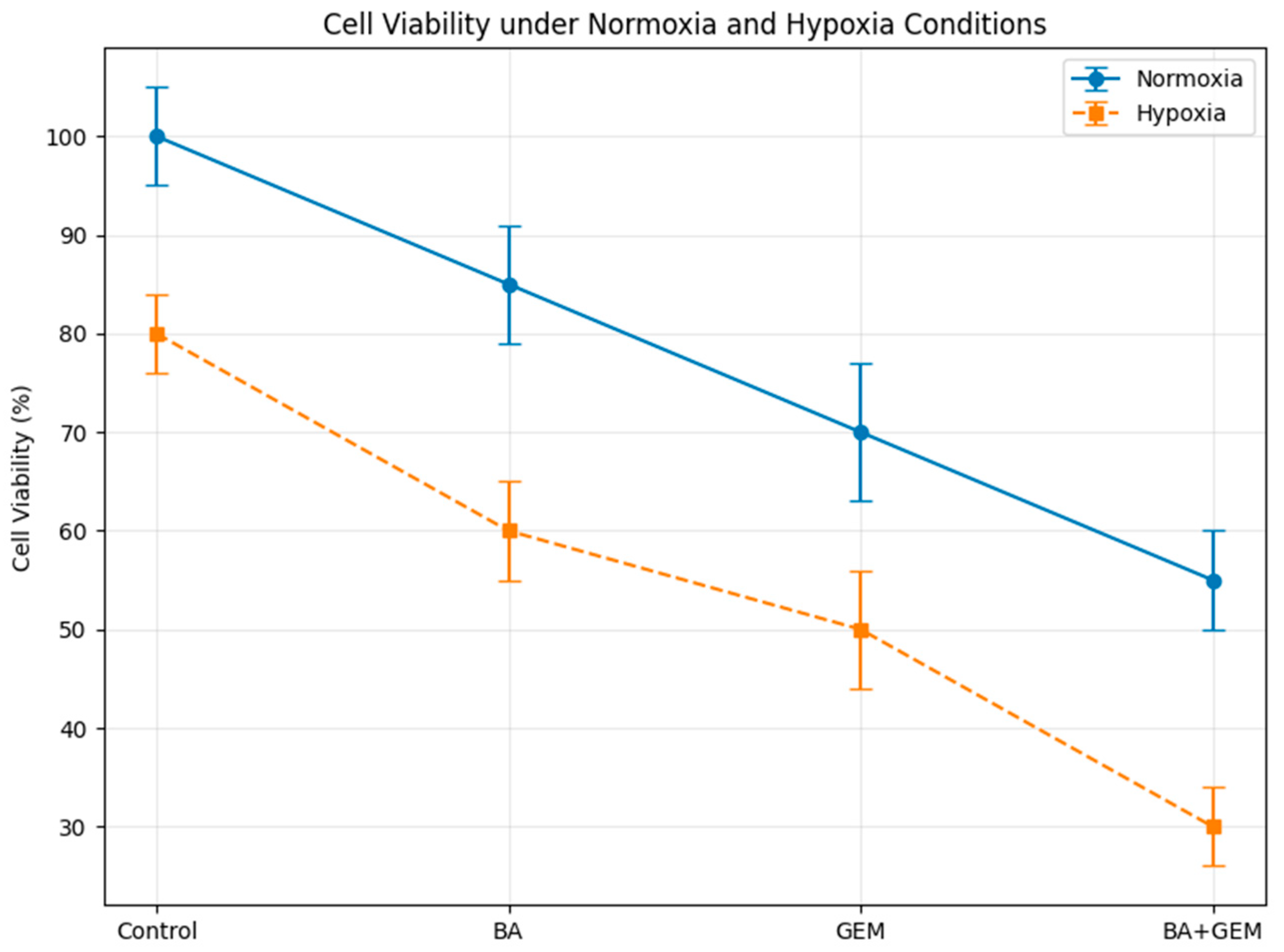

2.3. Induction of Hypoxia Using a Controlled Gas Incubator

To mimic hypoxic conditions, ECC-1 cells were incubated in a tri-gas incubator (Galaxy® 48R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) supplied with a premixed gas cylinder (1% O2, 5% CO2, and 94% N2; Linde Gas, Munich, Germany) for 24 h. Normoxic controls were maintained at 21% O2 in a standard humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The successful induction of hypoxia was functionally verified by the upregulation of HIF-1α and VEGF mRNA expression, as determined by qRT-PCR analysis, both of which are established transcriptional markers of cellular hypoxic response.

2.4. MTT Cell Viability Assay

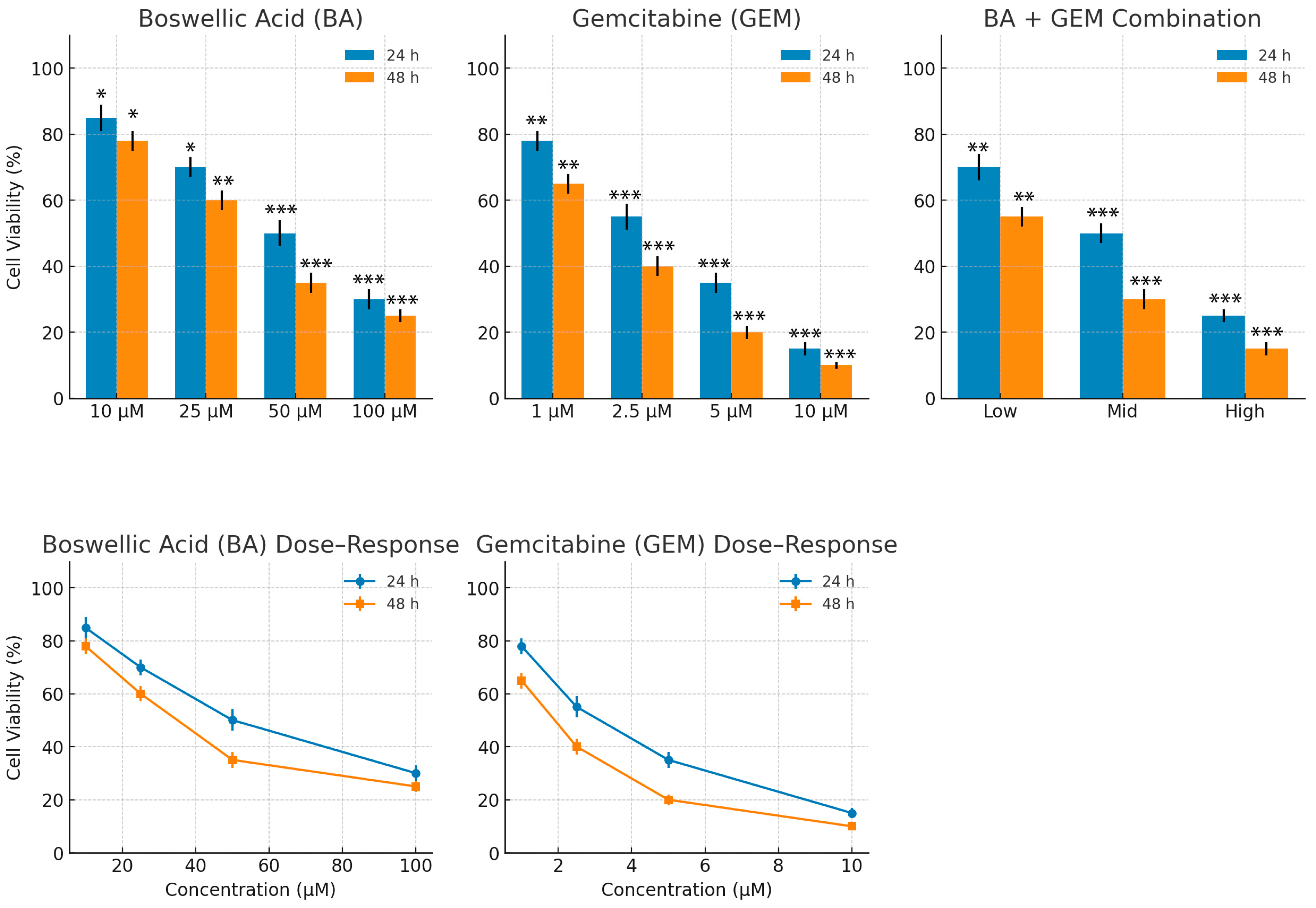

The cytotoxic effects of the treatments were evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). ECC-1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and treated with the indicated experimental conditions. Following treatment, MTT reagent (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The resulting formazan crystals were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Multiskan GO microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

Dose–response curves were generated from cell viability data, and half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were calculated using nonlinear regression (log(inhibitor) vs. response, variable slope) in GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each IC50 value was derived from at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

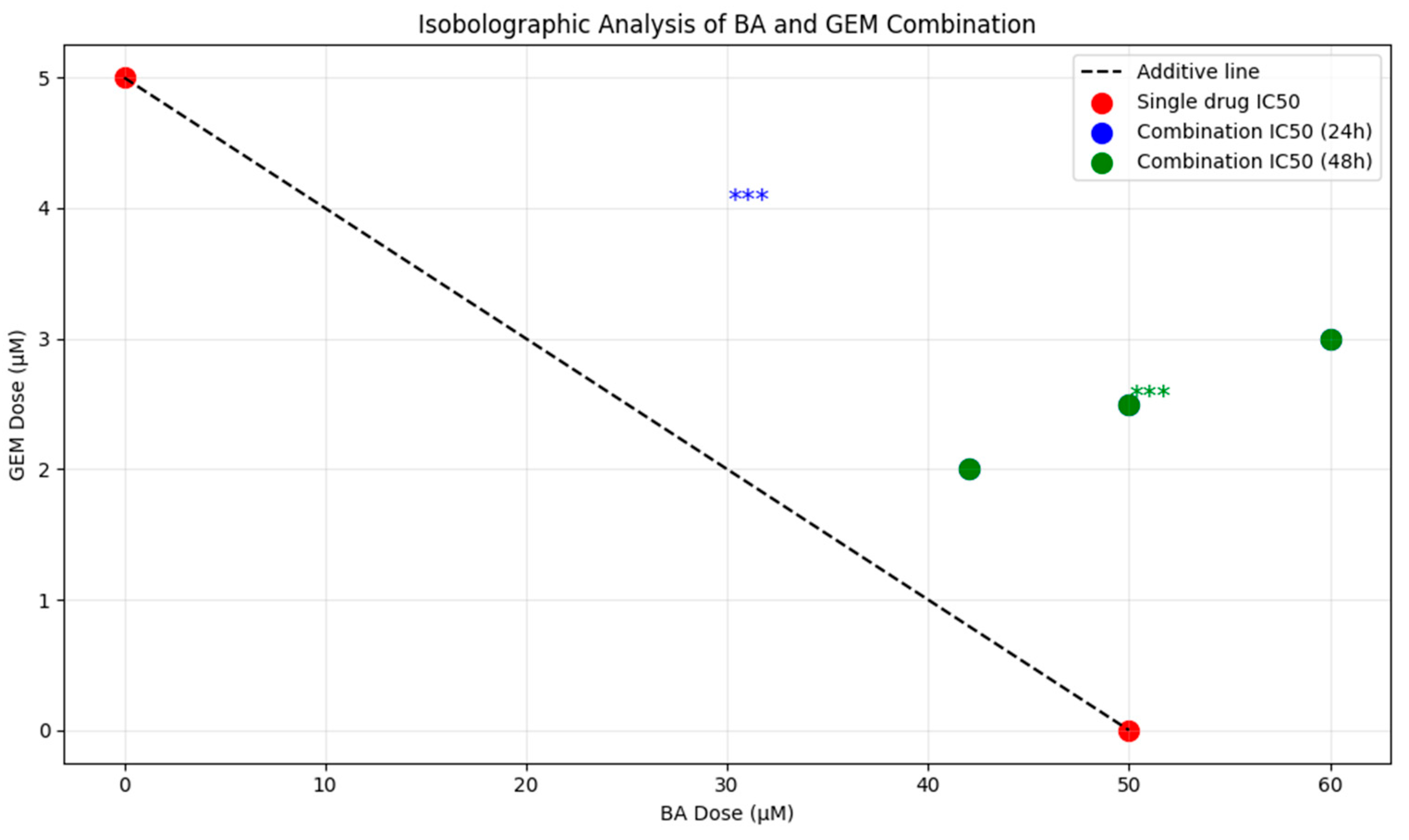

Drug interaction effects between BA and GEM were evaluated using the Chou–Talalay method. Combination index (CI) values were calculated based on the median-effect equation with CompuSyn software version 1.0 (ComboSyn Inc., Paramus, NJ, USA). CI < 1.0 indicated synergism, CI = 1.0 indicated additivity, and CI > 1.0 indicated antagonism. Isobologram plots were generated to visualize the nature of the drug interactions.

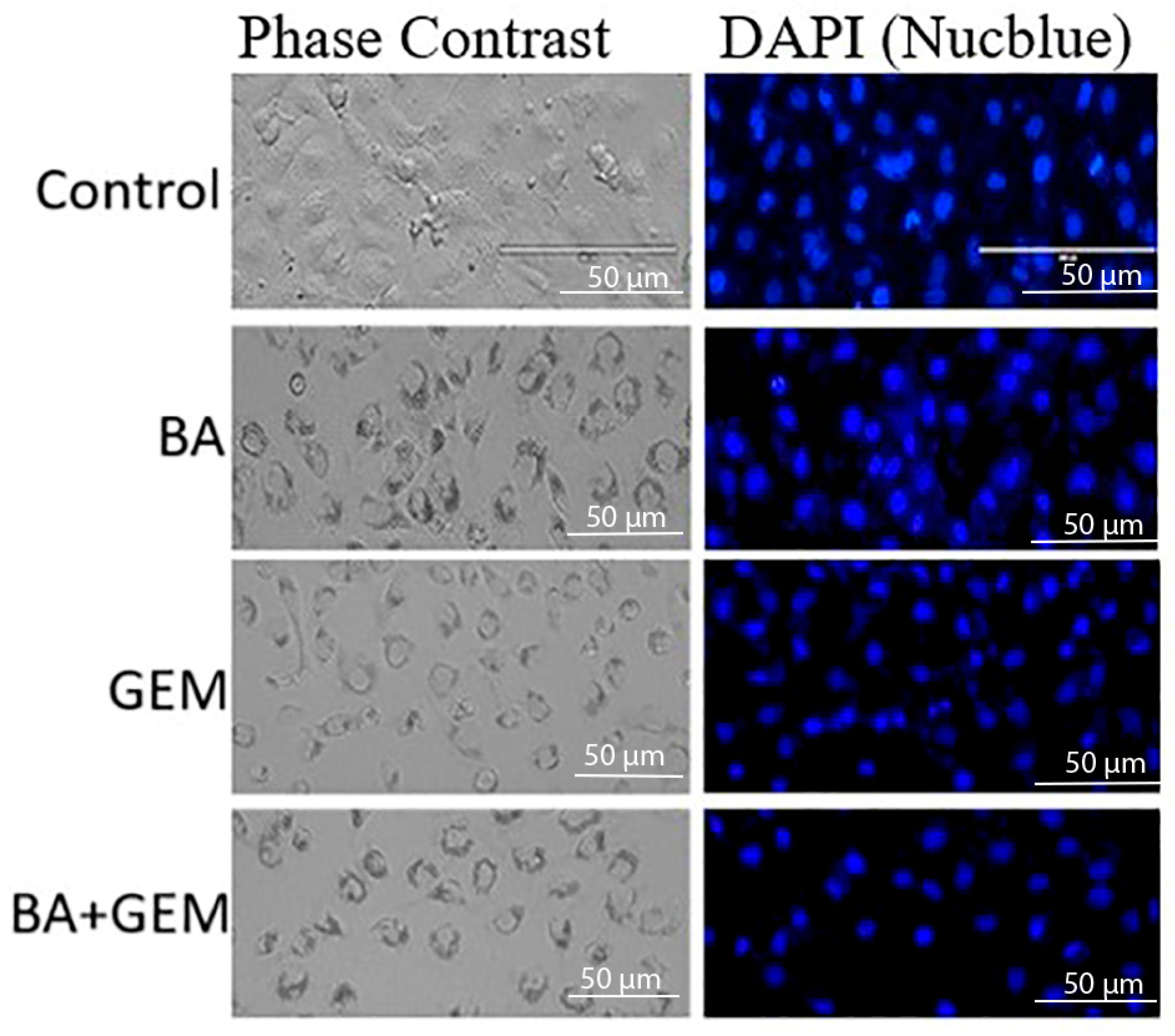

2.5. Nuclear Morphology Analysis Using Phase-Contrast and NucBlue (DAPI) Staining

NucBlue™ Live ReadyProbes™ Reagent (Hoechst 33342; Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA) was used to assess nuclear morphology. ECC-1 cells were cultured in 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and treated according to the designated experimental groups, followed by gentle washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). NucBlue solution (1 drop per 1 mL of culture medium), prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions, was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. After staining, cells were washed with PBS and examined under a fluorescence microscope equipped with a DAPI filter set (excitation/emission: 350/461 nm; Nikon Eclipse Ti2, Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). Apoptotic nuclear changes, such as chromatin condensation and fragmentation, were recorded, and representative images were captured using a digital camera system (DS-Qi2, Nikon Instruments, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Cell Cycle Distribution Analysis by Propidium Iodide (PI) Staining and Flow Cytometry

Cell cycle distribution was assessed using propidium iodide (PI) staining. Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at −20 °C for 24 h and subsequently incubated with RNase A (100 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and PI (50 µg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Samples containing at least 10,000 cells were analyzed using a BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Cell cycle distribution (G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases) was determined with FlowJo software, version 10 (BD Biosciences, Ashland, OR, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

2.7. Quantification of Apoptosis by Annexin V-FITC and Propidium Iodide (PI) Double Staining Using Flow Cytometry

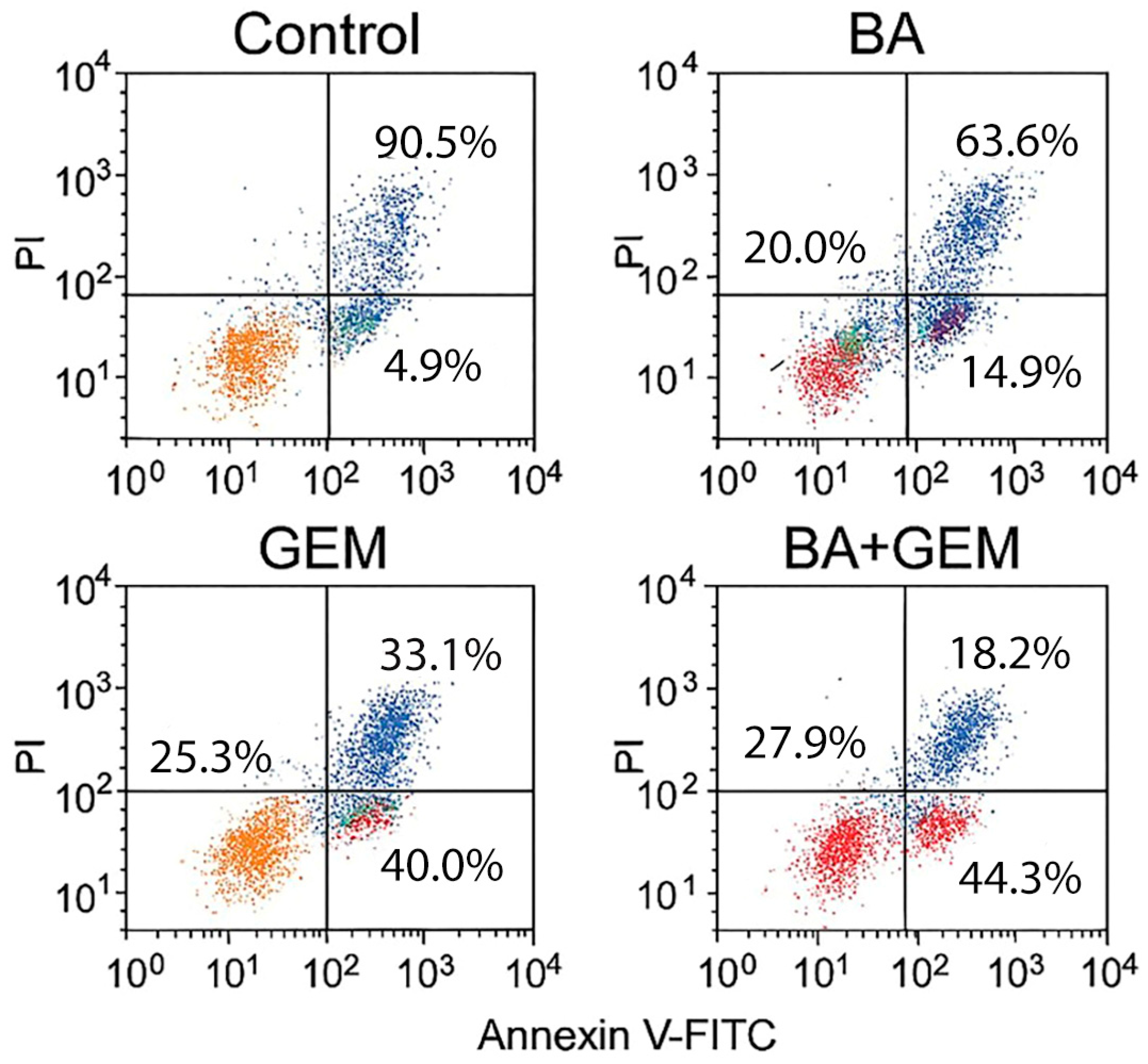

Apoptotic cell death was further evaluated using an Annexin V-FITC/Propidium Iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. ECC-1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and treated with BA, GEM, or their combination at IC50 concentrations for 48 h. After treatment, cells were harvested, washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and resuspended in binding buffer. Annexin V-FITC and PI were added, and the samples were incubated for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Fluorescence signals were analyzed with a BD FACSCanto™ II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), and data were processed using FlowJo software version 10 (BD Biosciences, Ashland, OR, USA). Cells were classified as viable (Annexin V−/PI−), early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI−), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), or necrotic (Annexin V−/PI+). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

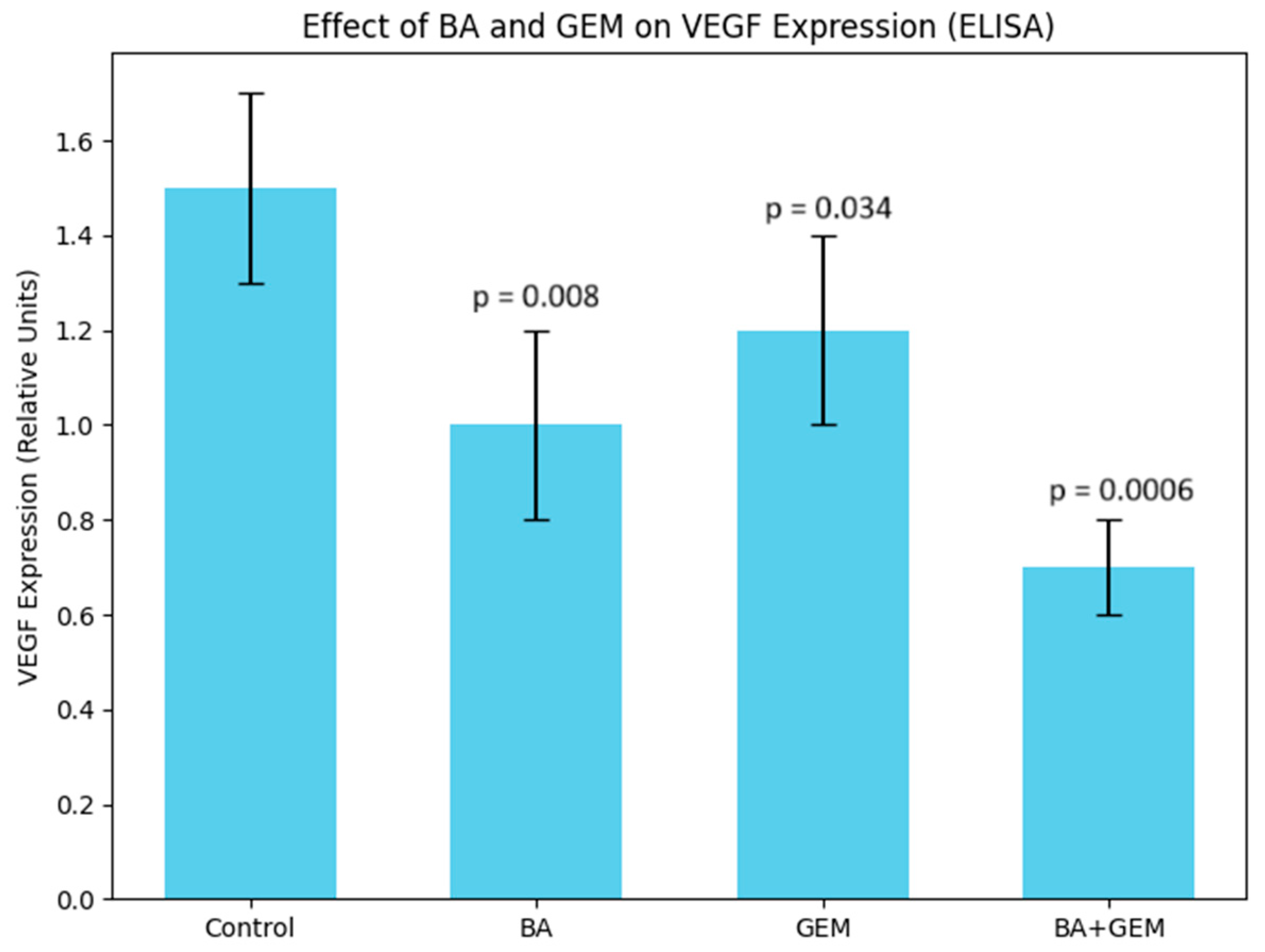

2.8. Evaluation of Angiogenesis Through VEGF Quantification by ELISA

The angiogenic potential was assessed by quantifying VEGF expression using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Cell culture supernatants were collected after drug treatment, and VEGF concentrations were measured with a Human VEGF Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA; Cat. No. DVE00), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was recorded at 450 nm with wavelength correction at 570 nm using a Multiskan GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

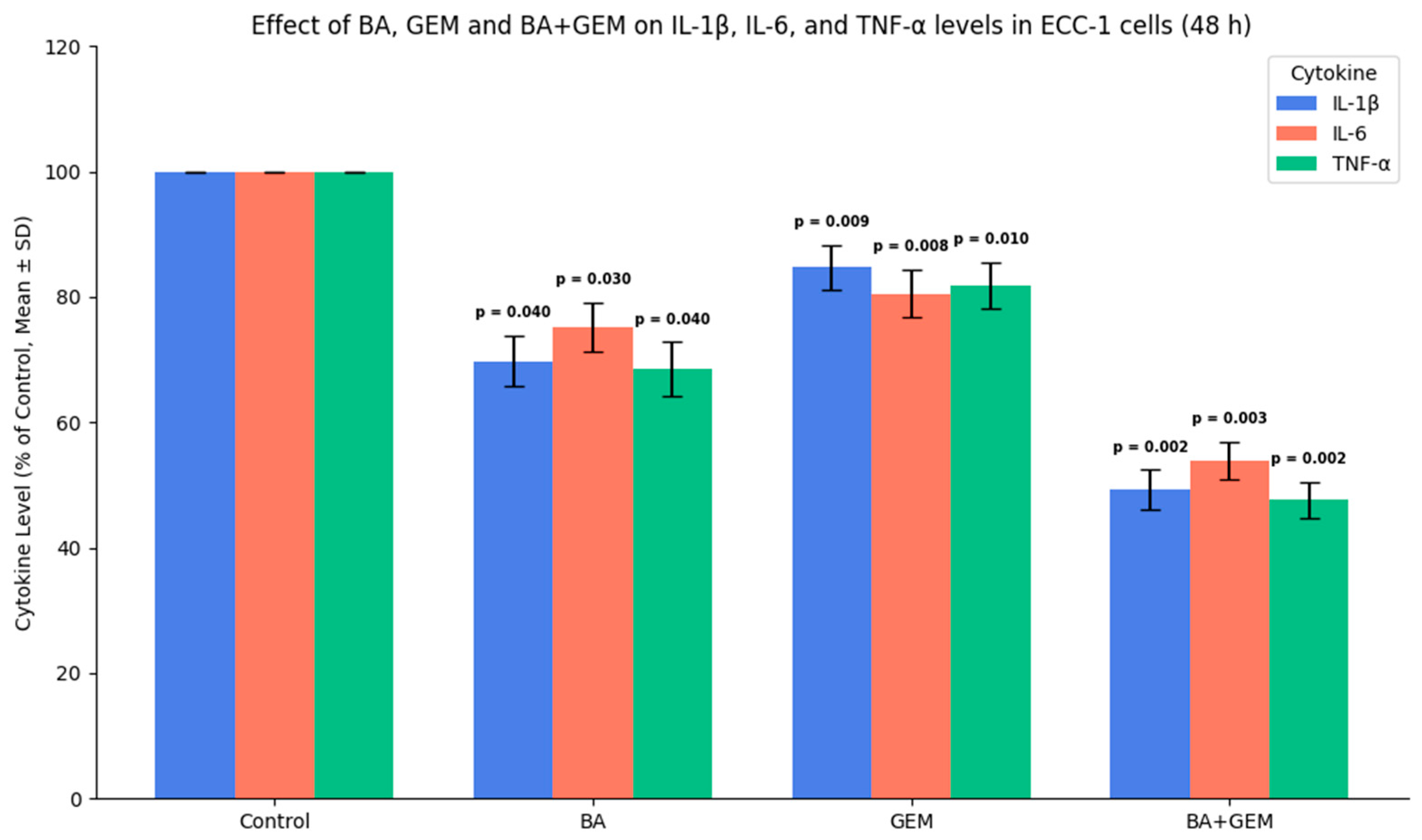

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) were quantified due to their known roles in promoting hypoxia, angiogenesis, and tumor progression.

2.9. Caspase-3/7, -8, and -9 Activity Assay (ELISA Method)

ECC-1 cells were treated with BA, GEM, and the BA + GEM combination for 48 h. After treatment, cells were lysed using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors, and the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 12,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. Invitrogen Human Caspase-3/7, -8, and -9 ELISA Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 168 Third Avenue, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to measure caspase activities according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One hundred microliters of each sample was added per well, and the colorimetric reaction was developed for 10 min at room temperature before adding the stop solution. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO ELISA reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Each sample was assayed in triplicate (n = 3) for statistical analysis.

2.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis of Hypoxia-, Angiogenesis-, and Apoptosis-Related Genes

The mRNA expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF, Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3 were determined using qRT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). qRT-PCR was carried out using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

Gene-specific primers for HIF-1α, VEGF, Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3 were designed using Primer-BLAST (NCBI) and synthesized by Sentegen Biotech (Ankara, Türkiye). GAPDH was used as the endogenous control. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

The primer sequences used for amplification are listed in

Table 1.

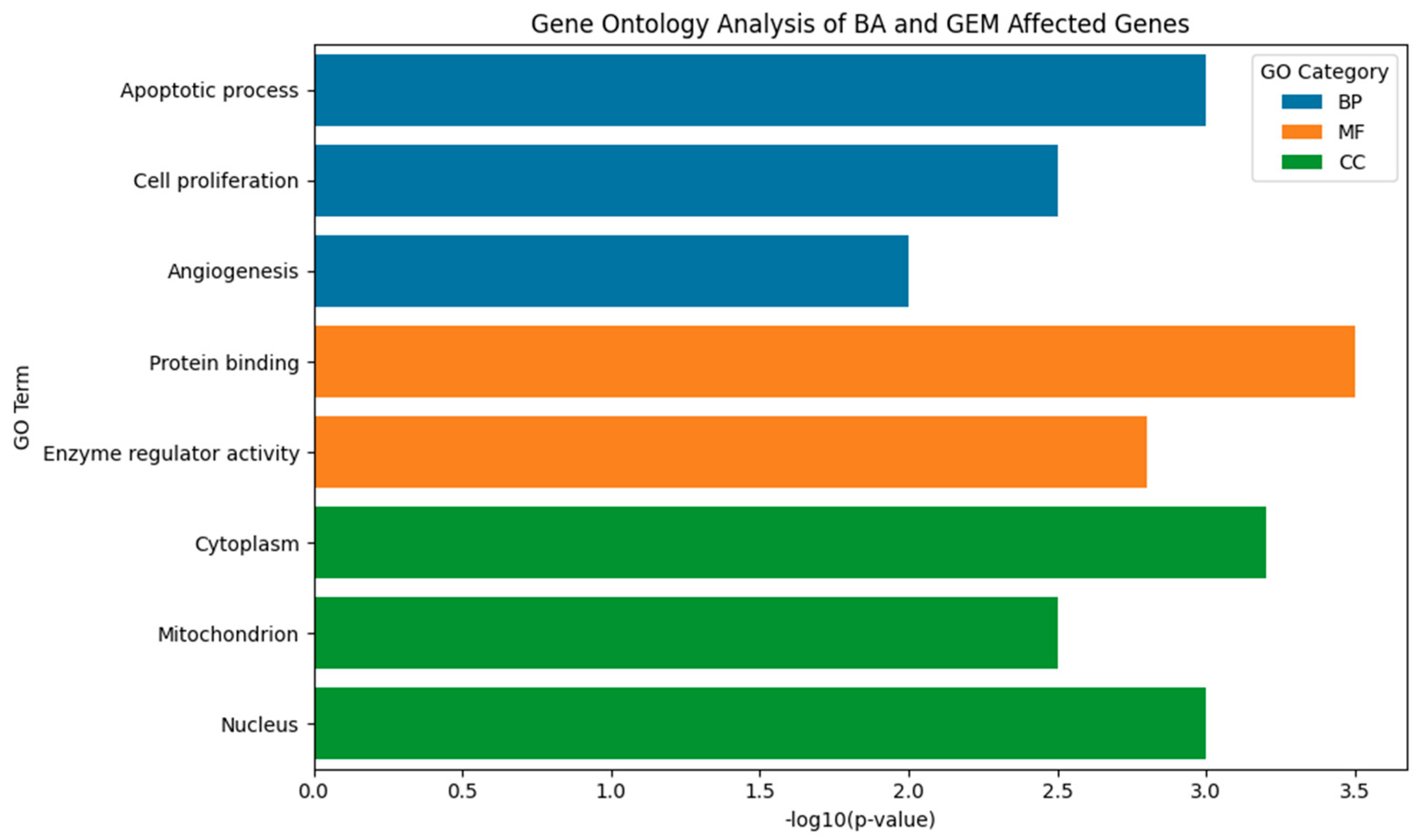

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v2024Q1. Enriched GO terms were visualized and plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). GO enrichment analysis was included to contextualize gene-level changes within broader biological pathways relevant to hypoxia, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.

2.11. Statistical Analysis of Experimental Data

All experiments were performed in at least three independent biological replicates (n ≥ 3). Each biological replicate contained three technical replicate measurements, and therefore all reported “n = 3” values refer to biological replicates unless otherwise specified. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data distribution was first assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between multiple groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) v2024Q1. Terms with adjusted

p < 0.05, false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.25, and fold change > 2 were considered statistically significant. Enriched GO terms were visualized and plotted using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The complete list of significant GO terms is provided in

Supplementary Files S1 and S2.

4. Discussion

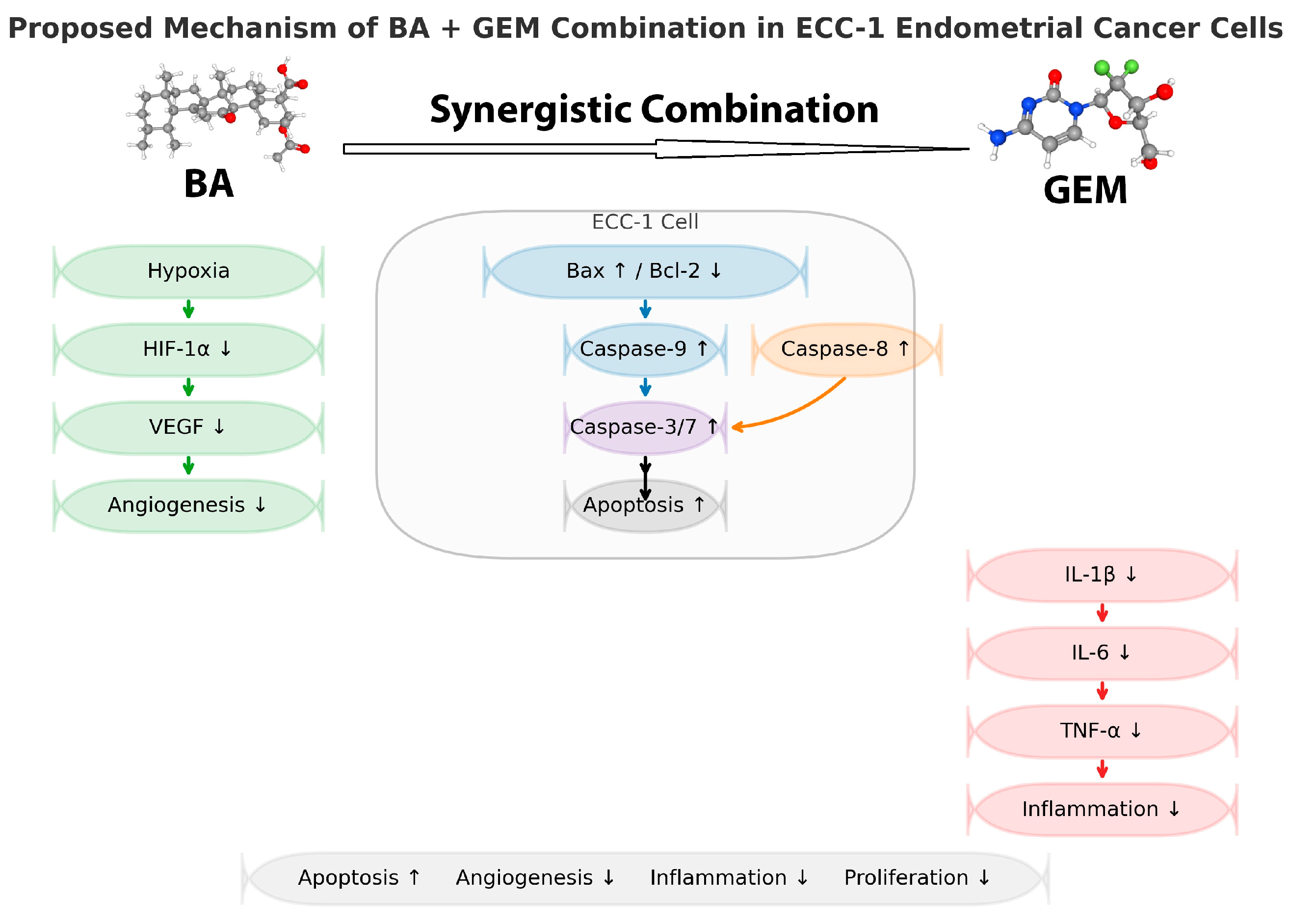

This study demonstrates that BA and GEM, individually and in combination, exert potent cytotoxic, anti-angiogenic, and pro-apoptotic effects against endometrial cancer cells. Both agents significantly reduced cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner, while their combined administration produced a pronounced synergistic effect, amplifying the anticancer potential beyond that of single-agent treatments. Importantly, the dual inhibition of key pathways involved in cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and apoptosis suggests that BA not only enhances the therapeutic efficacy of GEM but may also overcome some of the limitations associated with chemotherapy resistance. These findings suggest a potential mechanistic basis for combining natural bioactive compounds with conventional chemotherapeutics; however, therapeutic implications remain preliminary and require further validation.

MTT assays demonstrated that BA significantly reduced cell viability at doses of 25 µM and above after 24 h of treatment, whereas it became effective at concentrations as low as 10 µM after 48 h. GEM exerted a much stronger cytotoxic effect at lower doses, with significant reductions in viability observed starting at 1 µM and an IC

50 value of 1.29 µM. Consistent with our findings, the literature also indicates that GEM possesses a more potent anticancer potential than BA [

12]. Combination therapy produced an even stronger cytotoxic effect compared to either agent alone. At 24 h, the combination treatment reduced cell viability to below 10% at the highest dose, and after 48 h, viability decreased to 16%. Isobolographic analyses confirmed that the combination data points fell below the theoretical additive line, indicating a synergistic effect [

13].

The increasing preference for plant-based therapeutics with minimal adverse effects has significantly expanded the use of phytomedicines for the management of complex diseases such as cancer. Among these, boswellic acids (BAs), a group of widely recognized pentacyclic triterpenes derived from the oleogum resin, known as frankincense, obtained from Boswellia species, have attracted considerable scientific interest due to their diverse pharmacological potential. Various BA derivatives present in frankincense exhibit distinct bioactivities and therapeutic efficacies across different cancer types. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the anticancer properties of BAs, emphasizing their molecular mechanisms of action, involvement in signaling pathways, and the role of their semi-synthetic analogs in cancer prevention and therapy. In addition, it discusses the biological sources, conservation strategies, and biotechnological approaches aimed at optimizing in vitro BA production. Overall, the evidence summarized here underscores the broad-spectrum anticancer potential of BAs and their derivatives, supporting their further development as effective and economically viable agents in cancer treatment [

14]. Building on this evidence, our findings further demonstrate that under hypoxic conditions, BA potentiates the cytotoxic response of GEM in endometrial cancer cells. These findings suggest that hypoxia, a hallmark of the tumor microenvironment, not only contributes to disease progression but also amplifies the susceptibility of endometrial cancer cells to therapeutic intervention. The pronounced reduction in viability observed in the combination group implies that BA may enhance GEM’s activity under hypoxic conditions in vitro; however, whether this effect is sufficient to influence treatment resistance in vivo remains unknown.

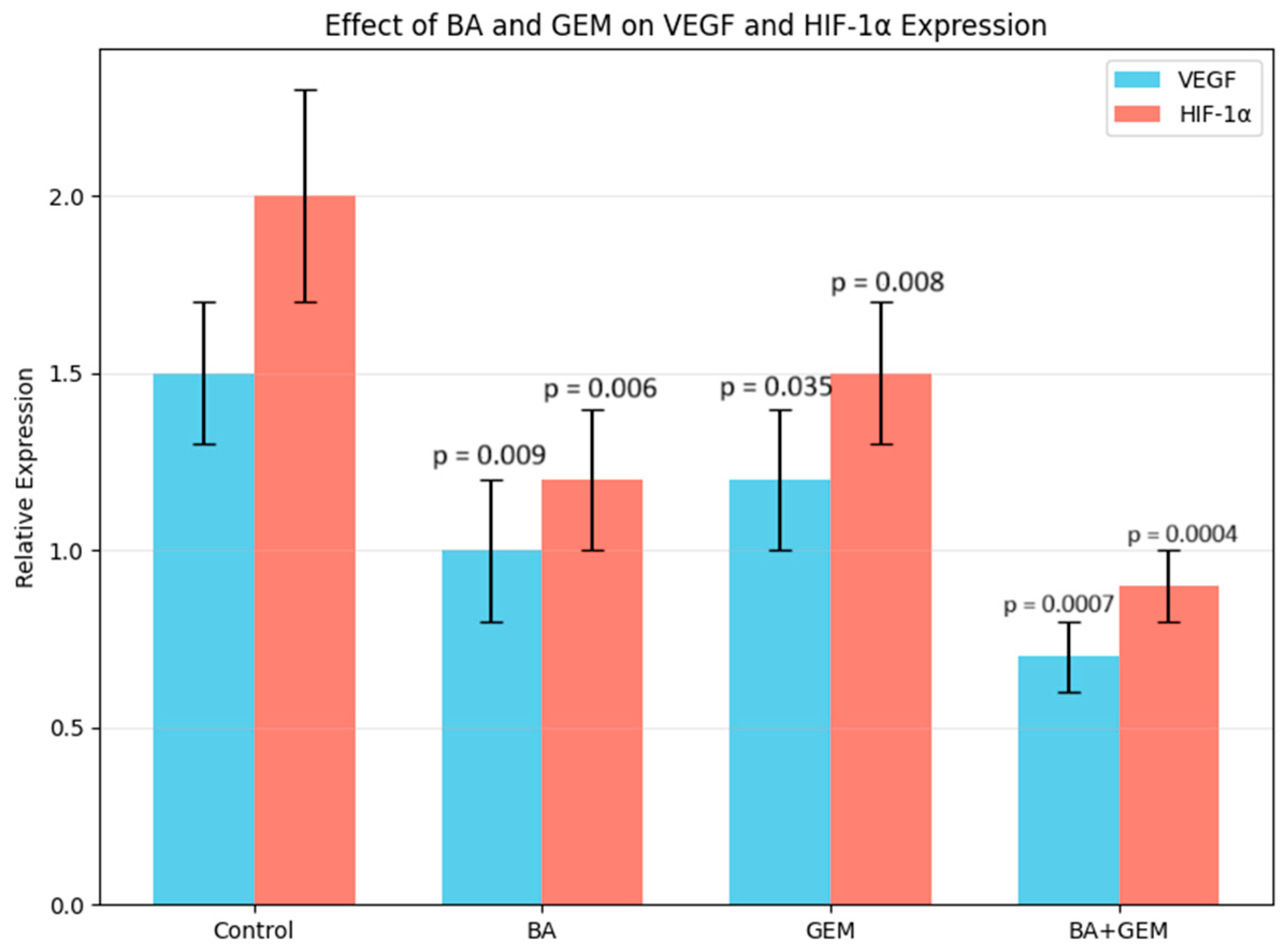

Angiogenesis assays showed that VEGF expression was significantly reduced by BA treatment, while GEM induced a moderate but measurable suppression. The BA + GEM combination produced the strongest inhibitory effect on VEGF expression, indicating a synergistic blockade of angiogenic signaling [

15]. Since VEGF is a critical downstream effector of hypoxia-driven HIF-1α activation and a key driver of neovascularization in endometrial cancer, its marked reduction suggests that BA and GEM may impair the vascular supply essential for tumor growth and survival. This suppression of angiogenesis not only contributes to decreased proliferative capacity but also enhances the overall cytotoxic impact of the treatments. Therefore, the combined downregulation of VEGF by BA and GEM highlights a dual mechanism of action: direct inhibition of tumor cell viability and indirect disruption of the tumor microenvironment through reduced angiogenesis.

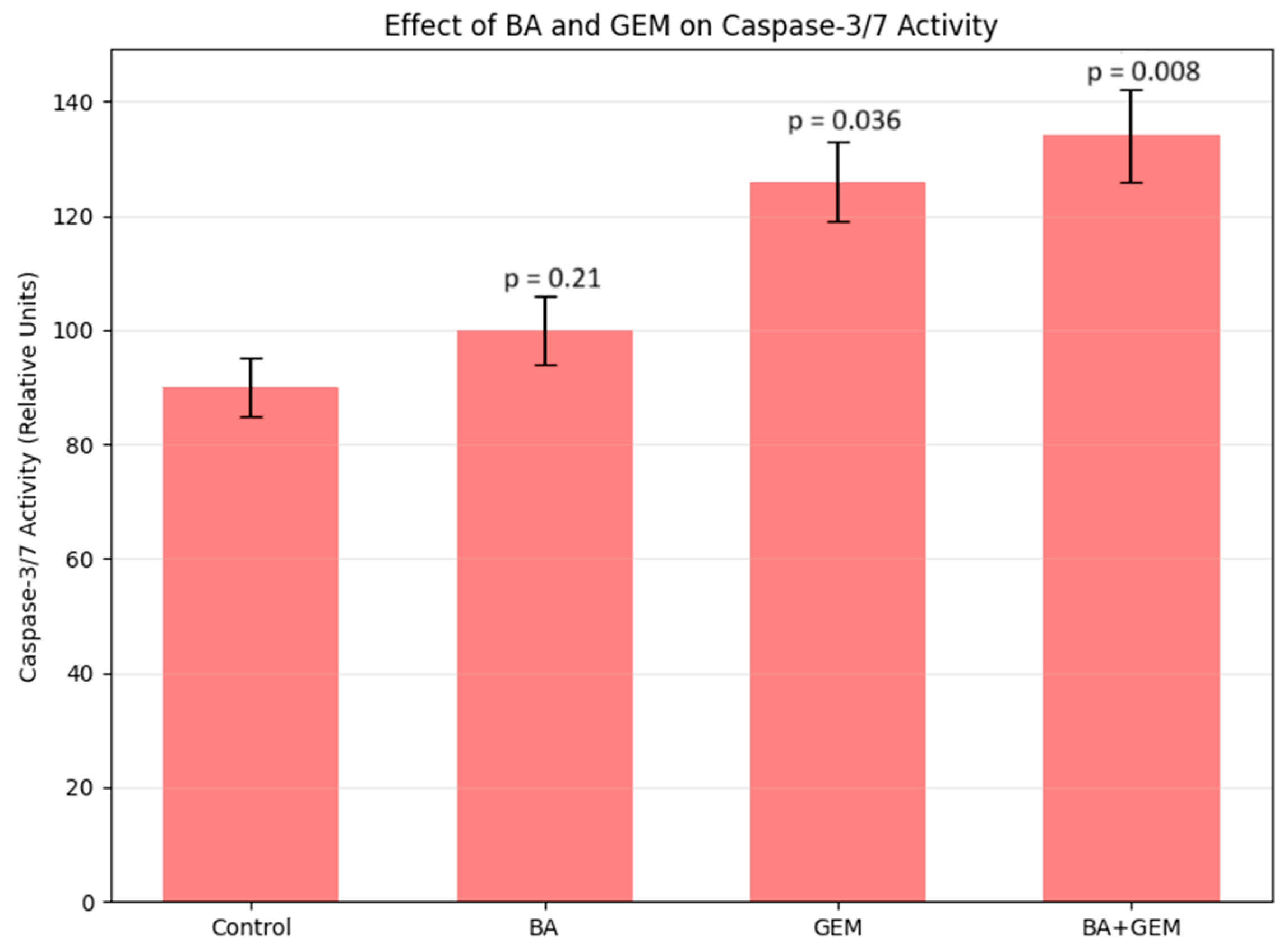

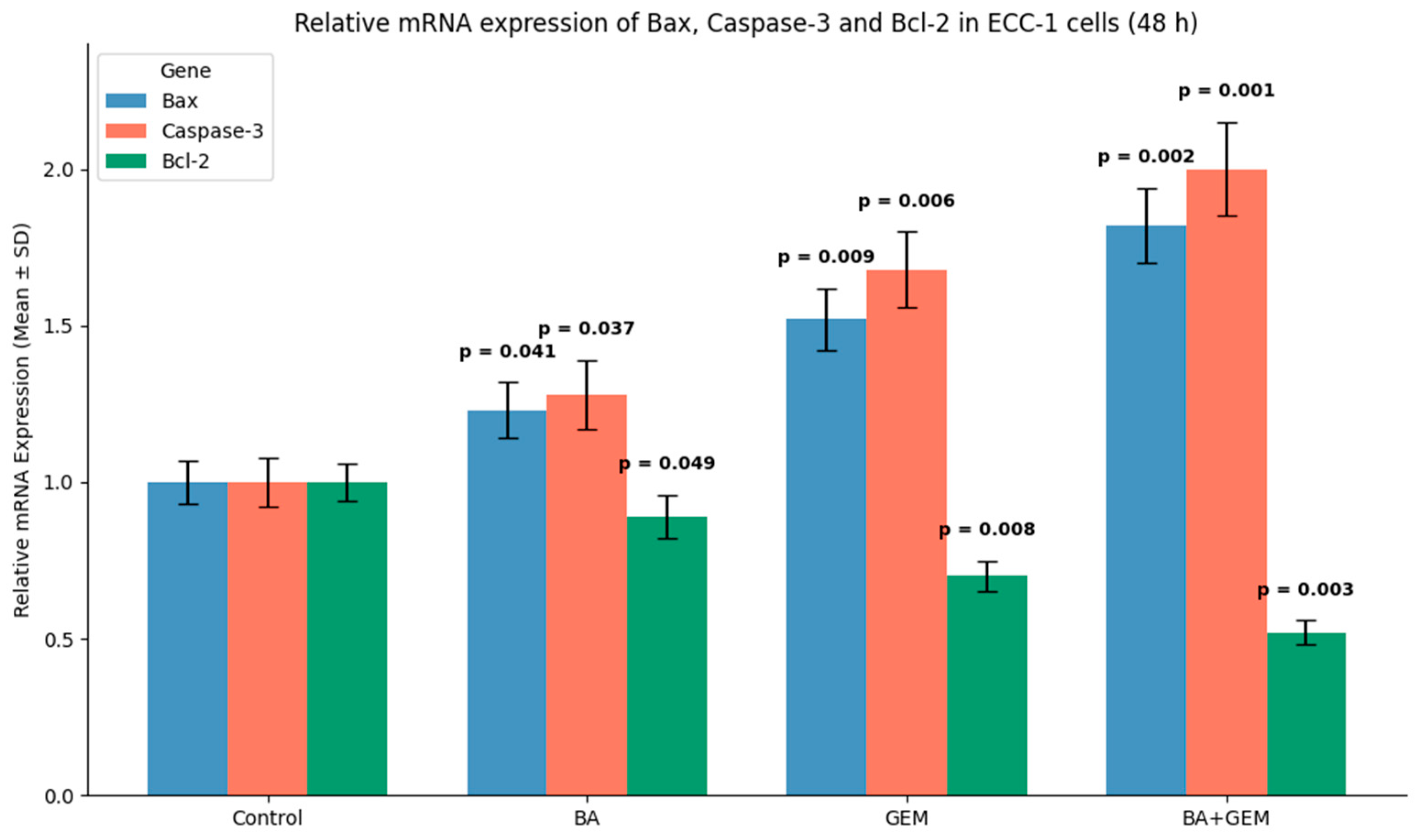

Analysis of apoptosis-related gene expression further supported these findings. BA treatment slightly increased Bax and Caspase-3 levels while decreasing Bcl-2 expression, consistent with studies showing that betulinic acid suppresses tumor growth through activation of mTOR-regulated apoptotic signaling and modulation of the Bax/Bcl-2/caspase axis. Likewise, GEM significantly upregulated Bax and Caspase-3 while downregulating Bcl-2, in line with findings demonstrating that gemcitabine induces apoptotic cell death in uveal melanoma cells by elevating Bax, activating cleaved Caspase-3, and altering Bcl-2 levels and that inhibition of Bcl-2 enhances GEM sensitivity. The BA + GEM combination maximized Bax and Caspase-3 expression and strongly reduced Bcl-2 expression, indicating that the combination therapy robustly activated mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis [

16,

17,

18]. Although the morphological alterations between GEM and BA + GEM groups appeared modest under phase-contrast microscopy, quantitative assays (MTT, Annexin V/PI, and Caspase-3/7 analyses) consistently demonstrated enhanced cytotoxicity and apoptosis with combination treatment, corroborating the observed microscopic trends.

In terms of inflammatory markers, BA treatment significantly reduced IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels, indicating a strong anti-inflammatory potential. GEM treatment also decreased these cytokines, although its effect was comparatively moderate. Notably, the BA + GEM combination induced the most profound suppression, markedly reducing the concentrations of all three cytokines [

19]. Since IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are well-established mediators of tumor-associated inflammation, their downregulation is mechanistically relevant. Elevated levels of these cytokines are known to promote tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), and resistance to apoptosis through activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways. Therefore, the observed decrease in cytokine levels suggests that BA and GEM may impair these oncogenic pathways, thereby attenuating the pro-tumorigenic microenvironment.

Importantly, the synergistic suppression observed in the combination group reinforces the notion that BA enhances GEM’s immunomodulatory capacity, leading to a dual effect: direct cytotoxicity on tumor cells and indirect inhibition of inflammation-driven tumor progression. These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting that natural compounds such as BA can reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine release, thereby augmenting the therapeutic efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutics. Collectively, the data indicate that BA and GEM not only inhibit cancer cell viability and angiogenesis but also modulate the inflammatory milieu in vitro. However, whether these changes meaningfully contribute to overcoming drug resistance or improving treatment outcomes remains uncertain and requires validation in additional cell models and in vivo studies.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis revealed that treatment-associated genes were significantly enriched in three main categories: biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Within the biological process category, genes modulated by BA and GEM were primarily involved in apoptosis, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis, underscoring their role in suppressing tumor growth and progression. The upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes (e.g., Bax and Caspase-3) together with the downregulation of anti-apoptotic and pro-angiogenic genes (e.g., Bcl-2, VEGF, and HIF-1α) highlights a coordinated reprogramming of cellular fate toward apoptosis and reduced vascular support. At the molecular function level, enrichment in protein binding, enzyme regulator activity, and signal transduction pathways indicates that BA and GEM interfere with key signaling cascades responsible for sustaining malignant phenotypes. These functions are particularly relevant to pathways such as NF-κB, STAT3, and PI3K/Akt, which regulate cell survival, inflammatory signaling, and angiogenesis. For cellular components, gene enrichment was concentrated in the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and nucleus—organelles central to apoptosis and transcriptional regulation. The mitochondrial localization of Bax and Caspase-3 is consistent with the activation of intrinsic apoptotic pathways, while nuclear changes suggest alterations in transcriptional programs related to angiogenesis and cell survival. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that BA and GEM target interconnected molecular networks at multiple cellular levels, thereby exerting a potent anticancer effect. Importantly, the combination treatment amplifies these effects, suggesting a systems-level reprogramming of tumor biology that may underlie the observed synergistic cytotoxicity [

20,

21].

Taken together, these findings suggest that the combination of BA and GEM holds strong potential as an adjuvant therapeutic strategy for endometrial cancer. By simultaneously targeting proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, and inflammation, the dual treatment appears to exert a systems-level impact on tumor biology that is greater than the sum of its parts. Importantly, the enhancement of therapeutic sensitivity under hypoxic conditions highlights its potential to overcome one of the major barriers to conventional chemotherapy. Nevertheless, while the in vitro results are compelling, further validation in preclinical animal models is necessary to evaluate pharmacokinetic properties, bioavailability, and possible systemic toxicities. In addition, clinical studies will be required to determine whether the observed synergistic effects translate into improved treatment response and patient outcomes. If confirmed, this combined approach could represent a novel therapeutic avenue to improve prognosis and reduce chemoresistance in endometrial cancer [

22,

23].

This study provides important mechanistic insights into the synergistic anticancer effects of BA and GEM in ECC-1 endometrial cancer cells. The ECC-1 line was chosen because it represents a well-differentiated, estrogen-responsive endometrial carcinoma subtype that stably expresses key apoptotic and angiogenic markers such as HIF-1α, VEGF, Bax, and Bcl-2, making it an appropriate model for hypoxia-related investigations. The synergistic combination of BA and GEM significantly suppressed HIF-1α and VEGF expression, enhanced Bax and Caspase-3/7 activation, and decreased Bcl-2 levels, collectively confirming the involvement of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although the mRNA expression profiles of Bax, Bcl-2, HIF-1α, VEGF, and Caspase-3, together with caspase activity assays, provide strong mechanistic insight, protein-level validation was not performed. The absence of Western blot or immunocytochemical confirmation limits the ability to directly correlate transcriptional changes with functional protein alterations. Future studies should incorporate protein-level analyses to substantiate these gene expression patterns and further elucidate the molecular interactions underlying the combined effects of BA and GEM in endometrial cancer cells. Second, although these findings provide strong mechanistic evidence, the use of a single endometrial cancer cell line limits the translational generalizability of the results. This model was selected to ensure experimental specificity; however, future studies should validate the observed synergistic effects using additional endometrial cancer cell lines (e.g., Ishikawa and HEC-1A) and normal endometrial epithelial cells, as well as in vivo and three-dimensional models that better recapitulate the tumor microenvironment. Third, cell viability in this study was assessed solely using the MTT assay, which primarily reflects mitochondrial metabolic activity rather than a direct measurement of live versus dead cells. Although MTT provides reliable quantitative information, complementary viability assays such as Trypan blue exclusion, live/dead fluorescent staining, or flow cytometry-based methods were not performed. Incorporating these additional techniques in future studies would provide a more comprehensive evaluation of cell survival and further validate the cytotoxic effects of BA and GEM. Finally, because this study was conducted using a single in vitro cell line model, any implications related to therapeutic potential, hypoxia-associated resistance, or clinical translation should be interpreted as preliminary. While the findings offer important mechanistic insight, further validation in multiple cell lines, 3D cultures, and in vivo models is required before any translational relevance can be established.

All findings were re-evaluated with validated statistical analyses and refined experimental parameters to strengthen methodological reliability. Furthermore, while Caspase-8 and -9 activities were quantified at the functional level, Western blot or immunofluorescence confirmation of their protein expression, along with pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiling of the BA + GEM combination, will be essential in future preclinical investigations. Collectively, the present study provides a robust mechanistic foundation and a promising framework for integrating natural compounds with chemotherapeutics to enhance treatment efficacy, overcome chemoresistance, and improve clinical outcomes in endometrial cancer.